Abstract

Oculo-ectodermal syndrome (OES - OMIM 600628), also known as Toriello Lacassie Droste syndrome, is a very rare condition, first described by Toriello et al., in 1993. OES has been proposed to be a mild variant of encephalocraniocutaneous lipomatosis (ECCL). It is characterized by aplasia cutis congenita (ACC), epibulbar dermoids, coarctation of the aorta, arachnoid cysts in the brain, seizure disorder, hyperpigmented nevi, non-ossifying fibromas and a predisposition to develop giant cell tumors of the jaw. There are few reported cases of OES worldwide but with no definite diagnostic criteria yet. We present a case in a child with unilateral hyperpigmented nevi and ACC on the scalp, ocular lesions (lipodermoid cysts and coloboma), temporal arachnoid cyst, spinal lipomatosis and aortic coarctation with the aim of enhancing the foundation to establish diagnostic criteria for this condition. It additionally serves as a teaching point to emphasize the importance of pursuing a definite diagnosis when faced with such a multisystem illness, to counsel patients and their parents regarding long term morbidity and overall prognosis.

Keywords: oculo-ectodermal syndrome, OES, Toriello Lacassie Droste syndrome

Introduction

Oculo-ectodermal syndrome (OES, OMIM 600268), was first described by Toriello et al., in 19931 and is characterized by aplasia cutis congenita (ACC), epibulbar dermoids, coarctation of the aorta, arachnoid cysts in the brain, seizure disorder, hyperpigmented nevi, non-ossifying fibromas and a predisposition to develop giant cell tumors of the jaw. Vascular anomalies predisposing to occlusive vasculopathy, recurrent transient ischaemic attacks and strokes have also been reported.3 The rarity of the condition and lack of definite diagnostic criteria poses a challenging problem for clinicians coming across such cases due to the myriad of clinical signs and symptoms which overlap with other conditions such as Epidermal Nevus syndrome.4

Seventeen cases have been reported previously and fifteen of them were reviewed by Ardinger et al., who suggested that OES may be a milder variant of encephalocranio-cutaneous lipomatosis (ECCL), lacking its intracranial anomalies.2 The patient being reported and those by Horev et al., were added to Table 1 comparing the previously reported fifteen cases of OES as compiled and reviewed by Ardinger et al., to further strengthen their hypothesis of the overlap between OES and ECCL. The etiology of OES is unknown and most of the cases have been sporadic. A case of a 5-year-old boy with a severe phenotype of OES demonstrated a de novo 36-kb deletion on Xq12 detected by oligonucleotide-based microarray.12 The authors recommend further testing of patients with OES and ECCL to see whether this mutation was unique to their case or could actually be the genetic cause for the similar neurocutaneous anomalies seen with OES and ECCL. The possibility of autosomal recessive inheritance was mentioned in a case with a severe phenotype where there was consanguinity between parents.11 However, more recent literature have implicated various possibilities, including that of a mutation of a tumor suppressor gene7 and a genetic defect in a transcription factor controlling ocular development.9

Table 1.

Comparison of recently reported patients with OES with those compiled and compared by Ardinger et al. in 20072.

| Patient 1; Toriello et al. (1993) | Patient 2; Toriello et al (1999) | Patient 3; Gardner and Viljoen (1994) | Patient 4; Gardner and Viljoen (1994) | Patient 5; Evers et al (1994) | Patient 6; Silengo et al (2000) | Patient 7; Gunduz et al (2000) | Patient 8; Lees et al (2000) | Patient 9; Lees et al (2000) | |

|

| |||||||||

| Sex | M | M | F | F | F | M | M | F | M |

|

| |||||||||

| Age last report | 5 years | 9 years | 3 years | Newborn | 16 months | 2 years | 2 weeks | 15 months | 1 year |

|

| |||||||||

| Skin | Appeared to be multiple myxovascular hamartomas | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Areas of ACC | Multiple | Multiple | Single | Single | Multiple | Single | Multiple | Multiple | |

|

| |||||||||

| Non-ACC alopecia or craniofacial lipoma | Oval area of alopecia appearance of smooth muscle hamartoma | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Skin tags | R pre-auricular | Chin & R mandible | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Other skin | Hyper-pigmented streaks | Hyper-pigmented areas | Hyperkeratotic lesion L temple | Syringomas (papules) forehead | R pre-auricular pit | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| Eyes | Bilateral | Bilateral | Bilateral | Left | Right | Left | Left | Left | Bilateral |

|

| |||||||||

| Epibulbar dermoid | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Upper eyelid defect | Small papilloma | Skin tag on L upper eye lid | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Other eye anomaly, cloudy corneas, retinal abn | Optic disc abn, retinal abn | Cloudy corneas | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Central giant cell granulomas of jaws | Noted at 4,5,6 years | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Non-ossifying fibromas of long bones | Noted at 6 years | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Brain CT/MRI | AV fistula brainstem | L arachnoid cyst | L temporal arachnoid cyst, asymmetry of cerebral hemispheres, mild dilatation of ventricles | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Spine MRI | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Skull abn | Skull defect | Parietal skull defect, asymmetry of anterior fontanel | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Growth | Slow | Normal | Normal | Normal at birth | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal |

|

| |||||||||

| Development | Normal | Normal | Normal | Newborn | Normal | Delay | Newborn | Normal | Delayed |

|

| |||||||||

| Other anomaly | ASD, small umbilical Hernia | Small umbilical Hernia | Seizures, fine growing fragile scalp hair | Bladder exostrohy, epispadias, aortic coarctation, embryonal rhabdomyo-sarcoma at 11 months | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| ECCL crtieria | Definite | Probable | Definite | Definite | Probable | Definite | Probable | Probable | Probable |

|

| |||||||||

| Patient 10; James and McGaughran (2002) | Patient 11; Federici et al (2004) | Patient 12; Lee et al (2005) | Patient 13; Martin et al. (2007) | Patient 14;Ardinger et al. (2007) | Patient 15;Ardinger et al. (2007) | Patient 16; Horev et al (2009) | Patient 17; Fickle et al. (2012) | Present Patient | |

|

| |||||||||

| Sex | F | F | F | F | M | F | F | M | M |

|

| |||||||||

| Age last report | 9 months | 6 years | 11 months | 6 years | 1 year | 6 months | 22 months | 5 years | 7 years |

|

| |||||||||

| Skin | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Areas of ACC | Single | Multiple | Single | Multiple | Multiple | Single | Multiple | Multiple | Multiple |

|

| |||||||||

| Non-ACC alopecia or craniofacial lipoma | Small area of fatty tissue above L eyelid | Large area of alopecia-smooth muscle hematoma on Bx | Soft tissue swelling over the L zygoma with consistency of a lipoma | Yellow subcutaneous nodules in L lid margin | None | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| Skin tags | R pre-auricular | L pre-auricular pit | L pre-auricular | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Other skin | Epidermal nevus like lesion | Linear yellow plaques on forehead | hyper-pigmented areas L side | Hyper-pigmented areas L side | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| Eyes | Right | Bilateral | Right | Left | Left | Left | Left | Bilateral | Right |

|

| |||||||||

| Epibulbar dermoid | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Upper eyelid defect | L upper eye lid defect | R upper eye lid defect | L upper eye lid defect | L upper eyelid defect | R upper eye lid defect | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| Other eye anomaly, cloudy corneas, retinal abn | L micro-phthalmia | Depigment-atition aroung R optic nerve | L eye proptosis due to L eye teporal dermoid cyst | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Central giant cell granulomas of jaws | Noted at 3,4,6 years | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Non-ossifying fibromas of long bones | Noted at 1 year | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Brain CT/MRI | Normal | Calcification of L globe, globular appearance of splenium of corpus callosum | 2 arachnoid cysts | L middle cranial fossa arachnoid cyst | Normal | Normal | R periventricular hypodense lesion, early moya moya disease | L prepontine cistern epidermoid | R temporal arachnoid cyst, absent R lacrimal gland, |

|

| |||||||||

| Spine MRI | Intra dural and intra spinal lipomas in cervico-dorsl-lumbar spine | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Skull abn | Anterior fontanel shifted to L | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Growth | Slow | Normal | Normal at birth | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal at birth | Normal | Normal |

|

| |||||||||

| Development | Delayed | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | Delayed | Normal |

|

| |||||||||

| Other anomaly | Microcephaly anterior anus, hypertonia, laryngomalacia | Coarctation of descending aorta, L hemiparesis due to abnormal cerebral vessels | Lower limb length discrepancy of unknown etiology | Long segment coarctation of descending aorta with hypertens-ion | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| ECCL crtieria | Probable | Probable | Definite | Definite | Definite | Definite | Definite | Definite | Definite |

|

| |||||||||

Case Report

We report a 7-year-old Egyptian boy, the second child of non-consanguineous parents with an older child having autistic disorder of unknown origin. He was the product of full term uncomplicated pregnancy, born by LSCS due to previous caesarean section. His birth weight was 3.2 kg and he had achieved all milestones appropriately. There was no history of neurocutaneous or seizure disorders in the family. According to parents, the child was born with “right eye lesions”, patchy areas of alopecia in the scalp, and skin lesions as described below. The eye lesions were diagnosed as a coloboma and epibulbar dermoid involving the right eye, but no definitive treatment was carried out at the time.

At the age of eighteen months, the child developed febrile status epilepticus and at 20 months afebrile focal clonic seizures which involved the right side. Seizures were treated with Levetiracetam and Carbamazepine. With the constellation of his congenital eye anomalies, skin lesions and seizures, the possibility of having a neurocutaneous disorder such as Epidermal Nevus syndrome or Goldenhar syndrome was raised with the parents. However, no definite diagnosis was made and the family had relocated to Qatar when the child was 6 years old. It was during one of his pediatric emergency visits in Doha, for a viral illness that the child was noted to have hypertension. Detailed scrutiny of his medical reports revealed that the child did have elevated blood pressure measurements which were in the range of 140-180 systolic and 75-100 diastolic at the age of 3 years. He was admitted to our institution at the age of 7 years for investigating the cause of his hypertension; which did indeed reveal a previously undetected, long segment coarctation of the descending aorta. This was medically managed by the pediatric cardiology team. Our pediatric neurology team was consulted for follow up of his epilepsy which was under good control at the time. Given the existing constellation of signs and symptoms, we performed a thorough literature search and tried putting the different parts of the puzzle into place to arrive at a conclusive diagnosis to counsel the family regarding long term morbidity and prognosis.

Physical examination

Upon presentation at the age of 7 years, his weight was 22 kg (25th percentile) and height was 116 cm (25th percentile). The child was alert and hyperactive. The following features were observed:

Skin

Hyperpigmented skin lesions exclusively on the left side of the body of variable sizes, extending over the nape of the neck (Figure 1), the left axilla with verrucal changes (Figure 2) and downward to the trunk and abdomen till the level of the umbilicus, anteriorly and posteriorly. A hypopigmented area was present over the lateral aspect of the left thigh. Three areas of congenital alopecia were noted, two over the right temporal area and another over the vertex of the scalp measuring 6(5 cm. These were clinically diagnosed as Aplasia Cutis Congenita (ACC), although no biopsy was taken (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Unilateral hyperpigmention of the trunk, back and axilla.

Figure 2.

Congenital Cutis aplasia.

Figure 3.

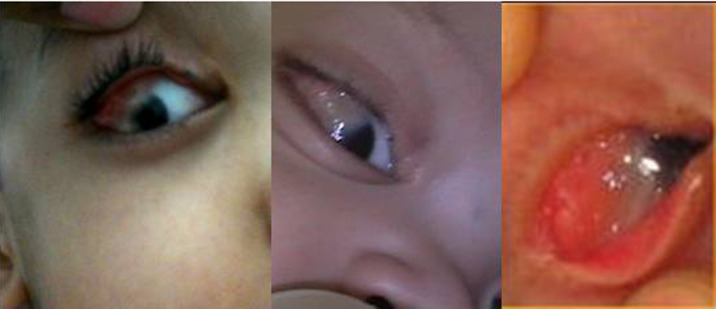

right The limbal dermoid seen encroaching onto the cornea, left – at birth (provided by the parents).

Ocular examination

Right eye examination showed congenital right-sided coloboma of the eyelid, strabismus with amblyopia and dermolipoma with a limbal dermoid at the superolateral limbus, extending over the cornea covering part of the visual axis (Figure 4). He was only able to count fingers at 3 meters which improved to 6/6 with glasses. Retinal structure and intraocular pressure were normal. The left eye was normal.

Figure 4.

CT angiogram showing long segment coarctation of descending aorta above the origin of superior mesenteric artery (as indicated).

The rest of the systemic and neurological examinations were normal. There was no evidence of non-ossifying fibromas involving the long bones.

Echocardiography

revealed long segment coarctation of the descending aorta measuring 2 cm with a pressure gradient of 25 mm Hg at the thoracic aorta and gradient of 40 mm Hg at the abdominal aorta.

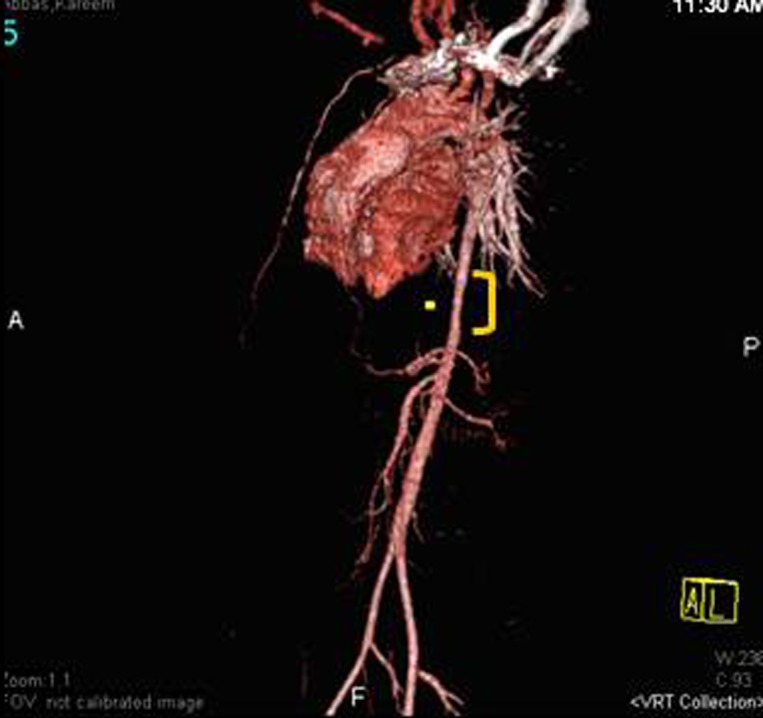

CT angiogram

of the abdomen revealed a 3.5 cm long segment descending and pre-renal aortic coarctation, which was 6 mm in largest diameter (Figure 5). An interesting finding in the CXR was the absence of rib notching that is usually seen in aortic coarctation.

Figure 5.

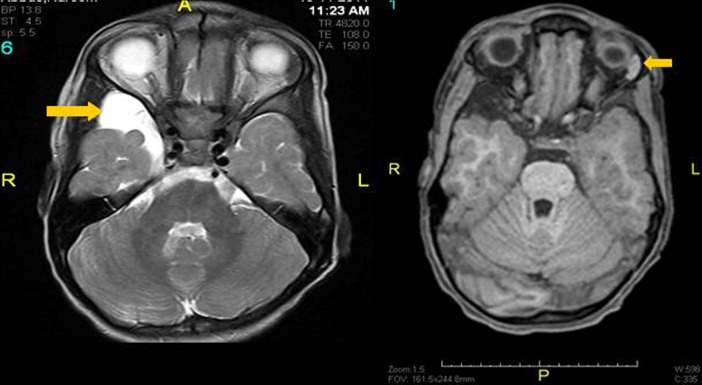

MRI Brain (right) axial tbl2WI showing bright right temporal arachnoid cyst (arrow head), and (left) tbl1WI showing absent right and normal left lacrimal gland (arrow head).

Brain and orbit MRI

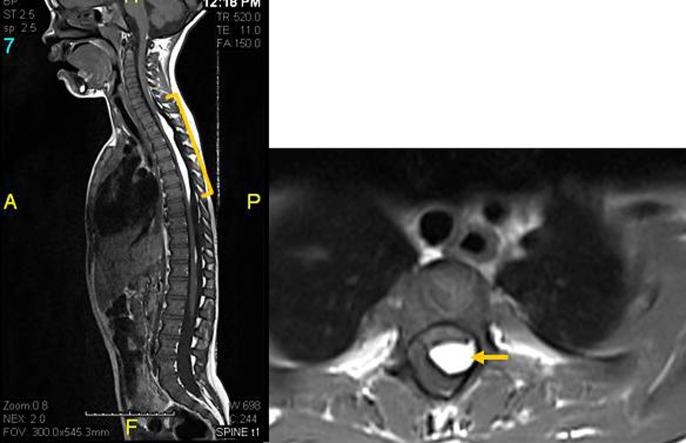

revealed a right temporal pole extra-axial arachnoid cyst causing mass effect on the right temporal lobe (Figure 6). There was neither intra-orbital extension of the dermolipoma nor any intracranial lipomas; however, absence of the right lacrimal gland was noted (Figure 5). MRI of the spine revealed posterior intra-spinal and intra-dural lipomas extending along the cervico-dorso-lumbar levels the largest at the cervico-dorsal region, indenting the dorsal spinal cord (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

MRI spine tbl1WI sagittal (left) and axial (right) showing bright intraspinal posterior intradural lipoma impressing the cord (arrows).

A diagnosis of oculo-ectodermal syndrome was made based on findings of ACC, epibulbar dermoids, coarctation of the aorta, arachnoid cysts in the brain, seizure disorder and hyperpigmented nevi in the patient.3 Genetic test results are still awaited, and whole genome sequencing was proposed to the family with the intention of identifying an affected gene, which was still being considered at the time of writing this article. Our case is the eighteenth case of OES to be reported in literature.

Discussion

Oculo-ectodermal syndrome is a very rare, neurodevelopmental syndrome with multisystem involvement (eye, skin, CNS and cardiovascular). The genetic basis has not been fully understood yet, however, Toriello1 suggested that a new dominant mutation is possible, and Fickie et al.,12 identified a de novo deletion of Xq12 as a possible causative mechanism. The etiology of the condition still remains unknown although there have been hypothesis linked to ECCL and Epidermal Nevus syndrome, quoting somatic mosaicism of a lethal gene.2

Encephalo-cranio-cutaneous lipomatosis is a very rare neurocutaneous syndrome of unknown etiology. Described in 1970 by Haberland and Perou, it is characterized by unilateral lesions in tissues of ectodermal and mesodermal origin: skin, eye, adipose tissue, and brain. A smooth, hairless fatty tissue naveus of the scalp, the so-called naveus psiloliparus (NP) is confirmed the dermatological hallmark of ECCL. Also ECCL is clinically characterized by lipomatous hamartomas on the face and scalp, ocular abnormalities, and ipsilateral malformations of the central nervous system. Aortic coarctation, progressive bone cysts, and jaw tumors have also been described in association with this condition. As all the cases of OES reported to date fulfill either definite or the probable diagnostic criteria of ECCL as put down by Hunter,8 it remains to be seen if the genetic defect is similar and the two conditions are in fact part of a clinical severity spectrum of a single disorder.

Conclusion

Our case further supports the proposal put forward by Ardinger et al., in 2007, that oculo-ectodermal syndrome could be a mild variant of ECCL without intracranial lipomatosis. The patient fulfills the definite criteria put forward by Hunter for diagnosis of OES and ECCL in 2006.8 Spinal lipomatosis proven by MRI have not been reported in any case of OES.4 The absence of the lacrimal duct in our patient has not been reported as part of this syndrome as far as we are aware. We suggest that brain and spinal MRI with angiography should be performed in all patients with suspected OES or ECCL to rule out intra- and extracranial lipomatosis and abnormalities of cerebral vessel structure like Moyamoya disease which would put such patients at an increased susceptibility for strokes thereby making it one of the main risk factors for increased morbidity and mortality.3 We also recommend serial follow-ups by a pediatric dentist and orthopedic surgeon as these children are prone to develop tumours involving the jaw and long bones, even at a young age.12 It is likely that with further clinical genetic understanding, this syndrome will become better delineated and that it may be a spectrum of severity in the phenotype of a single genetic disorder.

References

- 1.Toriello HV, Lacassie Y, Droste P, Higgins JV. Provisionally unique syndrome of ocular and ectodermal defects in two unrelated boys. Am J Med Genet. 1993;45:764–766. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320450620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ardinger HH, Horii KA, Begleiter ML. Expanding the phenotype of oculoectodermal syndrome: Possible relationship to encephalocraniocutaneous lipomatosis. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143A:2959–2962. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horev L, Lees MM, Anteby I, Gomori JM, Gunny R, Ben-Neriah Z. Oculoectodermal syndrome with coarctationof the aorta and moyamoya disease: Expanding the phenotype to include vascularanomalies. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2011;155:577–581. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moog U. Encephalocraniocutaneous Lipomatosis. J Med Genet. 2009;46:721–729. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.066068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silengo M, Lerone M, Seri M, Priolo M, Jarre L. New clinical findings in oculoectodermal syndrome. Clin Dysmorphol. 2000;9:39–41. doi: 10.1097/00019605-200009010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gardner J, Viljoen D. Aplasia cutis congenita with epibulbar dermoids: Further evidence for syndromic identity of the ocular ectodermal syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1994;53:317–320. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320530403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Federici S, Griffiths D, Siberchicot F, Chateil JF, Gilbert B, Lacombe D. Oculoectodermal syndrome: A new tumour predisposition syndrome. Clin Dysmorphol. 2004;13:81–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hunter AG. Oculocerebrocutaneous and encephalocraniocutaneous lipomatosis syndromes: Blind men and an elephant or separate syndromes? Am J Med Genet Part A. 2006;140A:709–726. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee TK, Johnson RL, MacDonald IM, Krol AL, Bamforth JS. A new case of oculoectodermal syndrome. Ophthalmic Genet. 2005;26:131–133. doi: 10.1080/13816810500228811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lees M, Taylor D, Atherton D, Reardon W. Oculoectodermal syndrome: Report of two further cases. Am J Med Genet. 2000;91:391–395. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(20000424)91:5<391::aid-ajmg14>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.James PA, McGaughran J. A severe case of oculoectodermal syndrome? Clin Dysmorphol. 2000;11:179–182. doi: 10.1097/00019605-200207000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fickie MR, Stoler JM. Oculo-ectodermal syndrome: Report of a case with mosaicism for a deletion on Xq12. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. 2011 doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.34294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]