Abstract

Objective

To ascertain whether the National Quality Forum (NQF)-endorsed time interval for adjuvant chemotherapy (AC) initiation optimizes patient outcome.

Background

Delayed AC initiation for stage III colon cancer is associated with worse survival and the focus of an NQF quality metric (<4 months among patients aged <80 years).

Methods

Observational cohort study of stage III colon cancer patients aged <80 years within the National Cancer Data Base (2003-2010). The primary outcome was 5-year overall survival evaluated using multivariate Cox regression. Aggregate survival estimates for historical surgery-only controls from pooled National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project trial data were also used.

Results

Among 51,331 patients (60.8±11.6 years, 50.2% male, and 77.3% white), 76.3% received standard (≤2 months) and 21.6% delayed (>2 and <4 months) AC. Earlier AC was associated with better five-year overall survival (standard, 69.8%; delayed, 62.0%; late [4-6 months], 51.4%; log-rank, p<0.001). Survival after late AC was similar to surgery alone (51.1%; Wilcoxon-rank sum, p=0.10). Compared with late AC, standard (Hazard Ratio [HR] 0.62; 95% CI 0.54-0.72) and delayed (HR 0.77; 95% CI 0.66-0.89) significantly decreased risk of death. Risk of death was also lower for standard AC compared to delayed (HR 0.81; 95% CI 0.77-0.86).

Conclusions

One in five stage III colon cancer patients initiates AC within the NQF-endorsed interval, but does not derive the full benefit. These data support strengthening current quality improvement initiatives and colon cancer treatment guidelines to encourage AC initiation within 2 months of resection when possible, but not beyond 4 months.

Introduction

Adjuvant chemotherapy (AC) improves survival among patients with resected, lymph node positive (stage III) colon adenocarcinoma and is part of national treatment guidelines.1-7 As metastatic disease in regional lymph nodes is an important predictor of systemic failure,8 there is reason to suspect early AC initiation in stage III patients may be beneficial. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated earlier administration was associated with better overall and disease-free survival.9 Although quality studies with little heterogeneity were analyzed, there were some important limitations. For example, both colon and rectal cancer patients were included. This is problematic because decisions about AC for colon cancer are generally based on post-operative pathology; whereas, decisions for rectal cancer are often based on pre-operative staging which could influence patient and provider expectations leading to fewer AC delays. Additionally, both stage II and III patients were included. As there remains controversy regarding which stage II patients are ‘high risk’ and firm recommendations regarding AC are lacking, this too could lead to variation in initiation.

Importantly, among patients for whom it is clearly indicated, the optimal time to AC initiation remains unclear. Minimizing practice variation by recommending a target time interval could offer patients more consistent expectations regarding care, optimize multidisciplinary colon cancer management, and provide clearly defined, uniform guidelines to inform quality improvement efforts aimed at standardizing cancer care pathways. For stage III colon cancer patients aged less than 80 years, the National Quality Forum (NQF) endorses AC initiation within 4 months as a quality metric.10 However, at least one other oncologic quality improvement initiative recommends an 8 week interval.11 Furthermore, existing data suggest the full benefit of AC is realized at a time point far earlier than the NQF metric.9,12-14

Using a primary data source with adequate sample size and not restricted to elderly Medicare beneficiaries, we sought to describe factors associated with delayed AC initiation and to ascertain the impact of early initiation among patients for whom it is clearly indicated. In so doing, we intend to evaluate the current NQF metric and delineate whether it represents the ideal time interval for optimizing patient outcome. Our main study hypothesis was AC initiation within the NQF 4 month metric improves patient outcome, but that this interval is too inclusive for ensuring all patients with stage III colon cancer receive optimal care.

Methods

Data

A prospectively maintained, hospital-based registry of cancer patients, the NCDB is a joint project of the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer (ACS CoC) and the American Cancer Society. It has accumulated over 25 million individual patient records and captures>70% of incident cancers in the US. Over 1,500 cancer centers participate, reflecting a range of patient care settings. Comprehensive discussions of the dataset have been published previously.15-17 National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) investigators were contacted and aggregate overall survival estimates from pooled trial data for a historical, surgery-only control group of stage III patients (n=340) were obtained.18 This study was considered exempt by The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center's Institutional Review Board.

Study Subjects

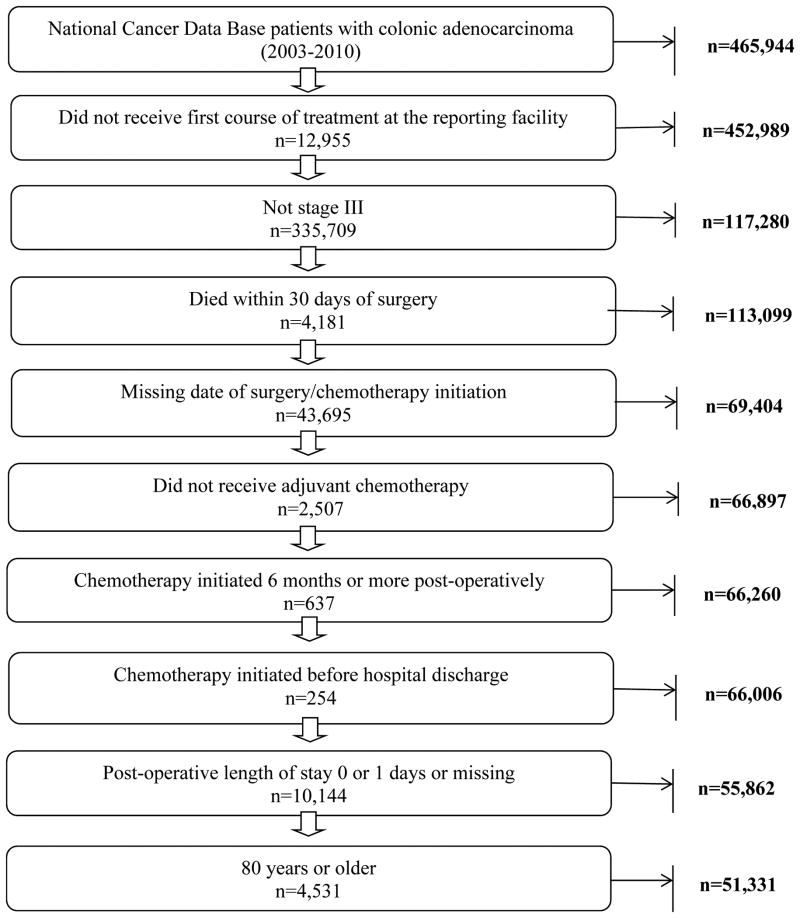

Figure 1 describes study exclusion criteria. Surgically resected stage III colon cancer patients (2003-2010) who subsequently received AC within 6 months were included. Patients diagnosed before 2003 were not included because comorbidity data were added to the dataset beginning that year. Patients initiating AC after 6 months were excluded to account for potential bias introduced by non-adjuvant utilization (e.g.: treating metastatic disease, locoregional recurrence, etc), patients with severe post-operative complications precluding earlier utilization, and patients who intentionally deferred earlier initiation. To be consistent with the NQF quality metric, the cohort was restricted to patients aged <80 years.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study design.

Variables

Demographic, clinical, and tumor data are provided in the NCDB. Indicators of income and education are provided (based on area of residence derived from Census 2000 data). A Charlson-Deyo comorbidity index is also provided. Time from resection to AC initiation was used to stratify into three groups: standard (≤2 months); delayed (>2 and <4 months); late (4-6 months). Since the NQF variably defines time to AC initiation as measured from diagnosis or resection,10,19,20 we evaluated the lag between diagnosis and resection and found it was relatively short (median 8 days; mean ∼14 days) with similar time intervals across AC categories. Therefore, consistent with previous work, AC initiation was measured from surgical resection.21 Two month categorization intervals were selected because: previous data suggest no survival difference between 4 and 8 week time intervals;13 randomized data suggest an 8 week time window potentially represents an interval beyond which further delays adversely affect survival;12 based on clinical experience, 2 months is a realistic and feasible time interval that not only allows patients adequate time to recover from surgery (accounting for delays due to minor complications), but also considers national waiting periods associated with chemotherapy initiation for colorectal cancer patients.22

Analysis

Standard descriptive statistics were used to define distributions of categorical and continuous variables. The primary outcome was overall survival. For the survival analysis, the cohort was restricted to patients diagnosed through 2005 (n=18,290) because complete, long-term follow-up is only currently available for patients diagnosed through 2005. When modeling risk factors associated with delayed AC initiation, the whole cohort was included. The log-rank test was used to assess overall survival and the Wilcoxon rank sum test was used when comparing to surgery controls (as individual NSABP data were not provided).

The association between time to AC initiation and risk of death was evaluated using multivariate Cox hazard regression. The assumption of proportional hazards was verified using the Kolmogorov-type supremum test (p=0.19). An interaction between age and time to AC initiation was considered; however, it did not contribute to model performance and was therefore excluded from the final model. The survival analysis was repeated among patients who had a short length of stay (LOS [≤7 days]) and no readmission (n=12,785) to represent patients for whom early AC initiation should have been possible (i.e.: no major post-operative complications that may have contraindicated early initiation). Logistic regression was utilized to examine factors associated with delayed AC initiation, defined as beyond 2 months (reference ≤2 months). Because the odds ratio approximation of the relative risk may be inaccurate as the outcome rate increases, odds ratios were converted and are presented as relative risk.23 A non-parsimonious approach was used in model construction with sex, age, race, insurance status, income, education, comorbid conditions, extent of operation, positive resection margin, and pathologic grade included as model covariates. Length of stay and readmission were not included in the main Cox model as the analytic cohort evaluated in the subgroup model was restricted/stratified based on these variables. However, these were included in the logistic model as were rurality and type of institution.

We performed several additional sensitivity analyses to better delineate the robustness of our findings. With respect to the survival analysis, AC initiation was modeled as a continuous variable (by week) and categorized into one moth time intervals. Additional time-dependent modeling using a single Heaviside function was also evaluated. But, the interaction between AC initiation interval and survival time was not significant; therefore, all analyses assume a baseline hazard. As cause of death is not available in the NCDB Participant User File, cancer-specific survival was assessed by modeling relative survival.24 In evaluating factors associated with delayed AC, the definition of “delay” was changed to beyond 4 months (reference ≤4 months).

Within the cohort, 17.0% of patients were missing at least one covariate data point (standard, 16.8%; delayed, 17.5%; late, 17.8%). Differences in survival based on missing data were neither statistically significant nor clinically meaningful (standard: 69.7% missing vs 69.8% non-missing, log-rank p=0.43; delayed: 61.0% missing vs 62.3% non-missing, log-rank p=0.92; late: 49.5% missing vs 51.7% non-missing, log-rank p=0.72). To ensure model results were robust to varying assumptions about missing data, we performed a case-complete analysis followed by an imputed analysis using ten sets of data obtained through multiple imputation by chained equations.25,26 Point estimates and inference from both analyses were similar so imputed results are reported. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute). Statistical comparisons were 2-sided and considered significant at the p<0.05 level.

Results

Among 51,331 patients, mean age was 60.8±11.6 years, 50.2% were male, and 77.3% were white. Overall, 76.3% and 21.6% of patients received standard and delayed AC, respectively, with similar proportions over the study period (74.2-80.5%, standard; 17.7-23.6%, delayed). Table 1 provides patient demographic and clinical characteristics. Median LOS for the cohort was 6 days. In the standard group, 90% of patients had a LOS of ≤9 days. Overall, 69.8% of patients had a LOS ≤7 days and no readmission and 83.1% had a LOS ≤10 days and no readmission.

Table 1. Patient and Facility Characteristics Stratified by Time to Chemotherapy Initiation.

| Time to Chemotherapy Initiation | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Standard (n=39,141) |

Delayed (n=11,095) |

Late (n=1,095) |

|

| Demographic Characteristics | |||

|

|

|||

| Mean Age ± SD, years | 60.4 ± 11.6 | 61.8 ± 11.4 | 62.1 ± 11.1 |

| Age, years (%) | |||

| ≤50 | 17.9 | 14.6 | 14.2 |

| 50-59 | 26.5 | 24.1 | 23.3 |

| 60-69 | 30.2 | 32.0 | 33.2 |

| 70-79 | 25.4 | 29.4 | 29.3 |

| Male sex (%) | 50.2 | 50.0 | 50.3 |

| Race (%) | |||

| White | 78.7 | 72.9 | 70.7 |

| Black | 12.2 | 16.4 | 17.4 |

| Hispanic | 4.8 | 5.9 | 8.2 |

| Other | 3.1 | 3.7 | 3.0 |

| Missing | 1.3 | 1.2 | 0.7 |

| Insurance status (%) | |||

| Private | 52.5 | 42.6 | 40.4 |

| Medicare | 37.7 | 42.6 | 41.9 |

| Medicaid | 4.0 | 6.8 | 8.6 |

| Other | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.9 |

| Uninsured | 3.7 | 5.6 | 6.6 |

| Missing | 1.3 | 1.5 | 1.6 |

| *Income (%) | |||

| ≥$46,000 | 37.9 | 34.7 | 33.8 |

| Missing | 5.9 | 5.7 | 4.6 |

| *Education (%) | |||

| ≥29% | 33.8 | 30.1 | 25.8 |

| Missing | 5.9 | 5.7 | 4.6 |

| Rurality (%) | |||

| Metropolitan | 77.3 | 77.5 | 77.9 |

| Suburban | 14.1 | 14.3 | 14.7 |

| Rural | 2.1 | 1.8 | 1.9 |

| Missing | 6.5 | 6.4 | 5.5 |

|

| |||

| Clinical Characteristics | |||

|

|

|||

| Comorbidity index (%) | |||

| 0 | 75.4 | 70.3 | 65.9 |

| 1 | 19.9 | 22.7 | 24.0 |

| ≥2 | 4.8 | 7.1 | 10.1 |

| Extent of Operation (%) | |||

| Partial colectomy | 90.4 | 88.0 | 88.3 |

| Total colectomy | 2.0 | 2.7 | 3.7 |

| Colectomy plus contiguous organ(s) | 6.8 | 8.5 | 7.3 |

| Colectomy, NOS | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.6 |

| Pathologic Margin Status (%) | |||

| Positive | 7.0 | 8.2 | 9.2 |

| Unknown | 0.8 | 1.2 | 1.1 |

| Number of Lymph Nodes | |||

| ≥12 nodes | 77.9 | 78.5 | 76.8 |

| Pathologic Grade (%) | |||

| Well-differentiated | 6.5 | 6.4 | 6.6 |

| Moderately-differentiated | 66.3 | 67.3 | 65.9 |

| Poorly-differentiated | 23.3 | 22.4 | 22.9 |

| Undifferentiated | 2.0 | 1.9 | 1.9 |

| Missing | 1.9 | 2.0 | 2.7 |

| Post-operative Length of Stay (%) | |||

| ≤7 days | 79.3 | 63.7 | 55.5 |

| 30-day Readmission (%) | |||

| Yes | 4.1 | 7.4 | 11.4 |

| Unknown | 2.7 | 3.0 | 3.0 |

| Time from diagnosis to surgery | |||

| Mean ± SD, days | 14.1 ± 20.9 | 14.9 ± 22.5 | 13.3 ± 19.7 |

| Time from surgery to AC initiation | |||

| Mean ± SD, days | 51.5 ± 23.8 | 89.8 ± 27.7 | 156.2 ± 25.1 |

|

| |||

| Facility Characteristics | |||

|

|

|||

| Hospital Type | |||

| Academic/Research | 23.2 | 30.9 | 27.7 |

| Comprehensive Community Cancer Center | 56.7 | 50.2 | 51.8 |

| Community Cancer Center | 19.0 | 18.0 | 19.8 |

| Other | 1.2 | 1.0 | 0.7 |

| Region | |||

| West | 12.4 | 13.8 | 13.8 |

| Midwest | 29.0 | 25.6 | 20.8 |

| Northeast | 19.5 | 22.7 | 19.8 |

| South | 39.2 | 37.9 | 45.6 |

Column percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding.

Based on 2000 census data. For income, the percentage of patients whose area of residence (based on year 2000 Census data) had a median household income ≥$46,000 is presented. For education, the percentage of patients whose area of residence (based on year 2000 Census data) had 29% or more adults who did not attain a high school education is presented.

Factors Associated with AC Delay

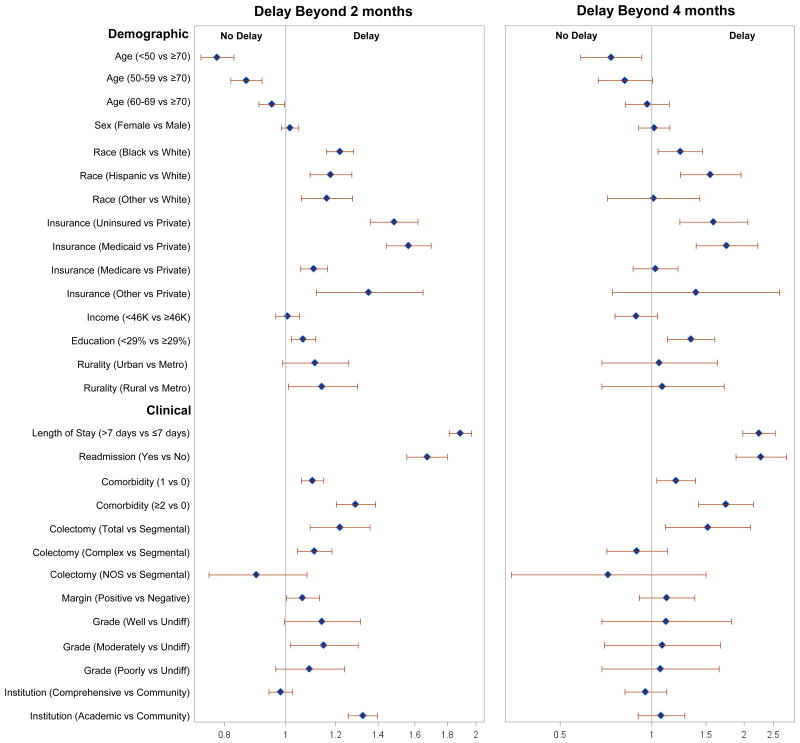

Several factors were associated with AC initiation beyond 2 months (Figure 2A), most notably LOS beyond 7 days (Relative Risk [RR] 1.89; 95% Confidence Interval [CI] 1.82-1.97) and readmission (RR 1.67; 95% CI 1.56-1.80). Compared to those with a Charlson of 0, greater comorbidity was associated with delayed AC (Charlson 1—RR 1.10; 95% CI 1.06-1.15; Charlson 2—RR 1.29; 95% CI 1.20-1.39). Younger age was associated with a lower likelihood of delayed initiation (<50 years—RR 0.78; 95% CI 0.73-0.83; 50-59 years—RR 0.87; 95% CI 0.82-0.92; 60-69 years—RR 0.95; 95% CI 0.91-1.00; 70-79 years—ref). As a sensitivity analysis, we varied the definition of ‘delay’ to beyond 4 months (reference <4 months). For many factors, the likelihood of delay was attenuated (Figure 2B). However, the magnitude of the effect for patients with LOS beyond 7 days (RR 2.24; 95% CI 1.98-2.54), readmission (RR 2.28; 95% CI 1.88-2.76), and greater comorbidity (Charlson 1—RR 1.20; 95% CI 1.04-1.39; Charlson 2—RR 1.75; 95% CI 1.42-2.15) remained significant and was accentuated.

Figure 2.

Relative risk associated with chemotherapy initiation delayed beyond 2 months (reference ≤2 months) and 4 months (reference <4 months).

Impact on AC Delays on Survival

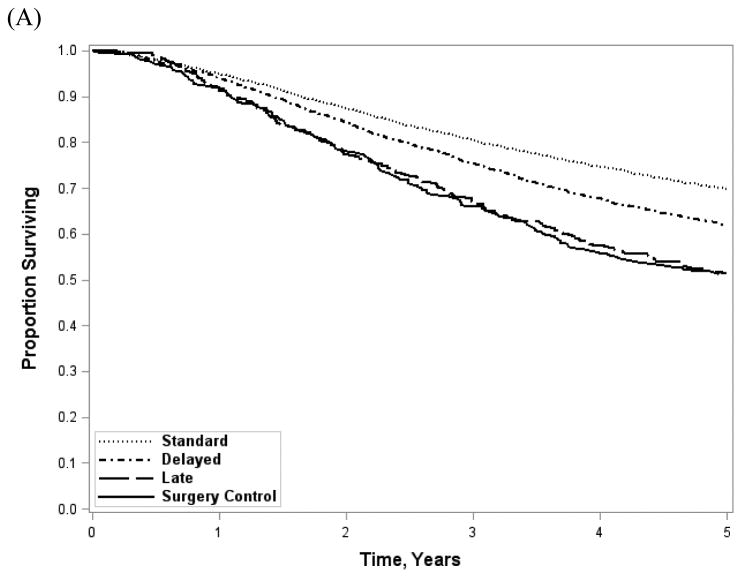

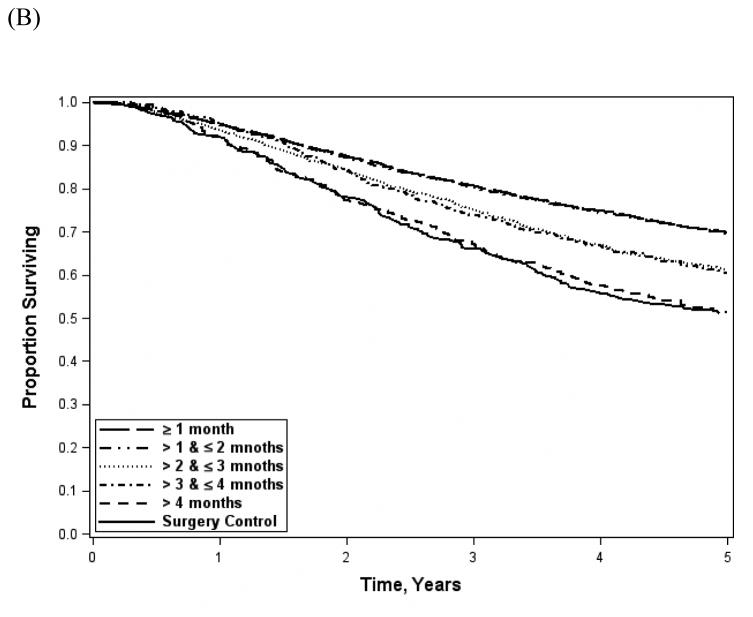

Demographic and clinical characteristic distributions for patients evaluated in the survival analysis were similar to the overall cohort. Overall survival (Figure 3A) was significantly better with earlier AC (standard, 69.8%; delayed, 62.0%; late 51.4%; log-rank, p<0.001). Survival among patients receiving AC after 4 months was similar to historical surgery-only controls pooled from NSABP adjuvant therapy trials (51.1%; Wilcoxon rank sum, p=0.10). The effect was similar among patients with short LOS and no readmission (standard 72.9%; delayed 68.1%; late 59.7%; log-rank, p<0.001). When stratified into 1 month intervals (Figure 3B), survival resembled the 2 month categorization scheme (≤1 month, 69.8%; >1 and ≤2 months, 69.6%; >2 and ≤3 months, 61.2%;>3 and ≤4 months, 60.6%; 4-6 months, 51.4%; log-rank, p<0.001). After adjustment for demographic and clinical factors (Table 2), there was a significant benefit for standard (Hazard Ratio [HR] 0.62; 95% CI 0.54-0.72) and delayed (HR 0.77; 95% CI 0.66-0.89) as compared to late AC. Similarly, standard AC patients had a survival benefit compared with delayed (HR 0.81; 95% CI 0.54-0.72). When the analysis was restricted to patients with a short LOS and no readmission, the survival benefit persisted for standard AC as compared to delayed (HR 0.88; 95% CI 0.82-0.96) or late AC (HR 0.71; 95% CI 0.57-0.90). However, delayed AC offered no benefit over late.

Figure 3.

Unadjusted overall survival stratified by time to AC initiation (A) and by 1 month time intervals (B). Log-rank, p-value<0.001 for both; Wilcoxon rank sum (surgery controls vs late AC), p=0.10.

Table 2.

Association Between Time-to-Initiation of Adjuvant Chemotherapy and Overall Risk of Death.

| Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Overall cohort | LOS ≤7 days and no readmission | |

|

| ||

| Chemotherapy Initiation | ||

| Late | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Delayed | 0.77 (0.66-0.89) | 0.81 (0.64-1.02) |

| Standard | 0.62 (0.54-0.72) | 0.71 (0.57-0.90) |

| Standard vs Delayed (ref) | 0.81 (0.77-0.86) | 0.88 (0.82-0.96) |

| Female Sex | 0.87 (0.83-0.92) | 0.89 (0.84-0.95) |

| Age, years | ||

| ≤50 | 0.67 (0.61-0.74) | 0.63 (0.56-0.72) |

| 50-59 | 0.69 (0.63-0.75) | 0.67 (0.60-0.75) |

| 60-69 | 0.76 (0.71-0.81) | 0.72 (0.66-0.78) |

| 70-79 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Race | ||

| White | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Black | 1.16 (1.08-1.24) | 1.17 (1.07-1.29) |

| Hispanic | 0.86 (0.75-0.97) | 0.98 (0.84-1.14) |

| Other | 0.83 (0.70-0.98) | 0.86 (0.70-1.05) |

| Insurance status | ||

| Private | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Medicare | 1.27 (1.19-1.36) | 1.29 (1.17-1.41) |

| Medicaid | 1.63 (1.44-1.85) | 1.51 (1.27-1.80) |

| Other | 1.01 (0.73-1.38) | 0.96 (0.63-1.45) |

| Uninsured | 1.36 (1.19-1.55) | 1.39 (1.17-1.65) |

| Income≥$46,000 | 1.06 (0.99-1.13) | 1.05 (0.97-1.14) |

| Education | 1.05 (0.99-1.13) | 1.09 (1.00-1.18) |

| Comorbidity index | ||

| 0 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | 1.21 (1.14-1.28) | 1.19 (1.10-1.28) |

| ≥2 | 1.75 (1.59-1.93) | 1.75 (1.53-1.99) |

| Extent of Operation | ||

| Partial colectomy | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Total colectomy | 1.21 (1.04-1.42) | 1.25 (1.01-1.55) |

| Colectomy plus contiguous organ(s) | 1.32 (1.22-1.44) | 1.34 (1.20-1.50) |

| Colectomy, NOS | 1.09 (0.86-1.39) | 1.09 (0.80-1.50) |

| Positive Margin | 2.08 (1.92-2.25) | 2.20 (1.98-2.44) |

| Pathologic Grade | ||

| Well-differentiated | 0.54 (0.44-0.67) | 0.49 (0.38-0.65) |

| Moderately-differentiated | 0.63 (0.52-0.76) | 0.65 (0.51-0.82) |

| Poorly-differentiated | 0.97 (0.80-1.17) | 1.00 (0.78-1.27) |

| Undifferentiated | 1.00 | 1.00 |

Sensitivity Analyses

Demographic and clinical variables were compared between patients excluded versus included in the subgroup survival analysis. Characteristics of those excluded appeared to favor patients more likely to experience a post-operative complication—older, higher burden of comorbid conditions, and more likely to have undergone a total or complex colectomy. In additional sensitivity analyses, we modeled 1 month (4 week) time intervals to address potentially meaningful survival differences based on a shorter AC time interval in the multivariate model. Compared to those receiving AC within 1 month, there was no difference in risk of death for patients who received AC between 1 and 2 months (HR 1.00; 95% CI 0.94-1.06); however, differences were significant beyond 2 months (3 months, HR 1.26; 95% CI 1.16-1.37; 4 months, HR 1.18; 95% CI 1.03-1.35; 5 months, HR 1.48; 95% CI 1.22-1.79; 6 months, HR 1.91; 95% CI 1.46-2.51). Time to AC initiation was also modeled as a continuous variable, using one week time increments—with each additional week of delay, risk of death increased by 3% (HR 1.03; 95% CI 1.02-1.03). A relative survival model was constructed to evaluate cancer-specific risk of death, with generally similar findings to the overall survival model: compared to late AC, there was a significant benefit for standard (HR 0.54; 95% CI 0.45-0.65) and delayed (HR 0.70; 95% CI 0.58-0.85); standard AC also demonstrated a survival benefit compared with delayed (HR 0.77; 95% CI 0.0.72-0.84).

Discussion

The NQF endorses a 4 month interval to AC initiation as a quality metric for stage III colon cancer. While inclusive and implicitly emphasizes administration of adjuvant therapy, the current NQF metric neither stresses the importance of early AC initiation and its impact on patient outcome nor informs the multi-disciplinary care pathway such that all eligible patients derive the full benefits of systemic therapy.9,12-14 In this regard, our evaluation of the NQF metric supports several conclusions. First, earlier AC initiation is beneficial in stage III disease, but the benefit attenuates beyond 2 months. Second, compared to pooled NSABP trial historical surgery-only controls, any survival benefit associated with AC appears mitigated after 4 months. Thus, patients receiving late AC likely experience the toxicity with minimal if any benefit. Third, consistent with prior work, 13 >75% of patients initiate AC within 2 months of surgical resection. Therefore, much of the care provided in the general community already exceeds this quality benchmark. More importantly, one in five stage III patients initiate AC within the NQF-endorsed time interval, but do not derive the full benefit. Thus, enhancing current national guidelines as well as strengthening the existing NQF quality metric to consistently recommend AC initiation within 2, but not beyond 4, months of resection could improve the multidisciplinary care provided to colon cancer patients.

The NQF is well-positioned to bridge the apparent existing gap between data and practice. The NQF's mission is to build consensus for and work towards achieving performance improvement, to endorse national consensus performance standards, and to attain goals though education and outreach.27 Currently, 85% of quality measures used in federal programs are NQF-endorsed and 90% of NQF measures are in use.28 Importantly, the NQF has demonstrated flexibility—augmenting, adding, and/or deleting metrics as data evolve.29 A greater emphasis on early AC initiation, not simply receipt of AC, is needed to move the bar for defining and measuring quality colon cancer care in the general community forward. A modified and enhanced NQF metric could both set a higher benchmark and provide a uniform, data-driven colon cancer AC initiation guideline which could raise both patient and clinician awareness of the importance of timely therapy.

Post-operative complications are common following colorectal cancer surgery and may be associated with delayed or omitted chemotherapy.21,30-32 Since post-operative complications are not “never events”, it may be reasonable to include parameters around this metric. For example, 90% of patients in our standard group had a LOS of ≤9 days and >80% of patients overall had no readmission and a LOS ≤10 days. Additionally, AC is frequently administered in the outpatient setting with a preponderance of care provided by private group practices.22,33 However, the NQF metric specifies this benchmark should be evaluated at the level of the treating facility. As the US healthcare system continues to evolve and Accountable Care Organizations become a more integral part, augmenting the quality metric to state AC should be initiated within 2 months for at least 80-90% of patients and tracking quality at the organizational, rather than the institutional, level may represent an equitable and actionable performance target.

Complications alone may not account for all AC delays. AC is omitted in one third of patients without a post-operative complication,31 suggesting clinical (e.g.: pre-existing comorbid conditions, patient frailty/deconditioning, etc.) and/or other patient factors (e.g.: lack of insurance, access to a medical oncologist, etc.) impact treatment decisions. Patients may delay AC initiation for personal reasons, particularly if not advised of the relationship between long-term outcome and earlier initiation.34 Alternatively, a lack of unified recommendations/quality targets or a failure by providers to recognize unnecessary delays may completely mitigate therapeutic benefit may also play a role. Pragmatically, a simple calculation of the number needed to treat reveals very few patients are required for efforts aimed at earlier AC initiation to be beneficial (13 patients currently initiating AC in 2-4 months would need receive it within 2 months; 9 patients currently initiating AC in 4-6 months would need receive it within 2-4 months; 5 patients currently initiating AC in 4-6 months would need receive it within 2 months).

There are important limitations to consider when interpreting our results. Selection bias and the generalizability of our results to patients receiving care at non-CoC hospitals must be considered.35,36 NCDB does not specifically report post-operative complications. However, our subgroup analysis of patients with short LOS and no readmission represented patients unlikely to have experienced a major surgical complication. The data neither specify which chemotherapeutic regimen patients received nor how many patients completed a full course of AC. NCDB does not provide information on the indication for chemotherapy administration or the reason for delays in initiation; therefore, we restricted our cohort to patients who initiated AC within 6 months of resection in an effort to only capture adjuvant indications. The data do not provide information on geographic provider density, which would speak to issues of patient access. Important patient-level factors, such as treatment preferences and performance status, are not specified. Similarly, the data do not fully capture or explain clinical decision-making based on provider intent.

Finally, although we had aggregate survival estimates for NSABP historical surgery-only controls, we did not have individual patient data to allow multivariate modeling. As such, the comparison to patient receiving AC after 4 months could be subject to bias. Despite this, there have been improvements in surgical technique and additional emphasis on oncologic surgical principles since the NSABP data utilized in this study were collected. In addition, randomization of NSABP patients occurred after surgical resection, suggesting surgical technique was not standardized or subject to rigorous surgical quality control. However, this lack of surgical quality control likely biased the comparison in favor of the late AC group; yet, survival was similar compared to no chemotherapy. NSABP member institutions represent a varied cross-section of practice settings, including a large proportion of community clinical oncology programs, similar to the majority of programs represented within the NCDB. Thus, although patients treated in randomized studies are often thought to have better outcomes than patients treated in the general community, we believe these factors support the generalizability of the NSABP data in this context and lend credence to the comparison in our study. Furthermore, because there is no longer equipoise with respect to the issue of systemic therapy administration for stage III colon cancer, there are unlikely to be future studies (randomized or not) where such patients are assigned to not receive chemotherapy. And, because systemic therapy is a standard part of treatment for stage III colon cancer patients in current practice (in large part because of data from the NSABP trials), a comparison to any contemporary cohort of patients who did not receive chemotherapy (but should have) would likely be inherently biased. For these reasons, although the NSABP data utilized in our work did not permit adjustment for all potential confounding variables, it likely represents the best available data to evaluate the important issue of a time threshold beyond which chemotherapy may not be effective.

Although the NQF metric provides a readily achievable target, it is suboptimal for ensuring all colon cancer patients receive the full benefit of AC. Our findings suggest a shorter interval (<2 months) would establish a higher bar for measuring quality and seta reasonable and actionable target. Our work also suggests a recommendation against AC initiation after 4 months couldsp are patients toxicity associated with seemingly non-beneficial therapy and reduce potentially unnecessary health care utilization and spending. Oncologic quality improvement initiatives should focus on enhancing multidisciplinary care coordination to facilitate referral to and consultation with medical oncologists and identifying perioperative processes that can minimize colorectal surgical complications. Benchmarking quality requires carefully chosen metrics that not only reflect attainable targets for care delivery, but also incorporate clinically meaningful care processes. Metrics not reflecting optimal care may cause providers to inadvertently miss opportunities to maximize the benefits of existing therapies.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute grant CA16672 (The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Support Grant).

Drs Massarweh and Haynes contributed equally to this work. The data used in this study are derived from a deidentified NCDB file. The American College of Surgeons and the Commission on Cancer have not verified and are neither responsible for the analytic or statistical methodology employed nor the conclusions drawn from these data. The authors would like to acknowledge Drs Neal Wilkinson and Greg Yothers who provided the aggregate survival estimates from the pooled NSABP trial data. The authors also thank Joe Munch for editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None of the authors has any conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Efficacy of adjuvant fluorouracil and folinic acid in B2 colon cancer. International Multicentre Pooled Analysis of B2 Colon Cancer Trials (IMPACT B2) Investigators. J Clin Oncol. 1999 May;17:1356–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andre T, Boni C, Navarro M, et al. Improved overall survival with oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment in stage II or III colon cancer in the MOSAIC trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009 Jul 1;27:3109–16. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.6771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laurie JA, Moertel CG, Fleming TR, et al. Surgical adjuvant therapy of large-bowel carcinoma: an evaluation of levamisole and the combination of levamisole and fluorouracil. The North Central Cancer Treatment Group and the Mayo Clinic. J Clin Oncol. 1989 Oct;7:1447–56. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1989.7.10.1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moertel CG, Fleming TR, Macdonald JS, et al. Levamisole and fluorouracil for adjuvant therapy of resected colon carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1990 Feb 8;322:352–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199002083220602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolmark N, Rockette H, Mamounas E, et al. Clinical trial to assess the relative efficacy of fluorouracil and leucovorin, fluorouracil and levamisole, and fluorouracil, leucovorin, and levamisole in patients with Dukes' B and C carcinoma of the colon: results from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project C-04. J Clin Oncol. 1999 Nov;17:3553–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.11.3553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Colon Cancer. [Accessed June 29, 2013]; http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp.

- 7.NIH consensus conference. Adjuvant therapy for patients with colon and rectal cancer. JAMA. 1990 Sep 19;264:1444–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laubert T, Habermann JK, Hemmelmann C, et al. Metachronous metastasis- and survival-analysis show prognostic importance of lymphadenectomy for colon carcinomas. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-12-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biagi JJ, Raphael MJ, Mackillop WJ, et al. Association between time to initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy and survival in colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2011 Jun 8;305:2335–42. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Quality Forum. National Voluntary Consensus Standards for Quality of Cancer Care. [Accessed July 3, 2013]; http://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2009/05/National_Voluntary_Consensus_Standards_for_Quality_of_Cancer_Care.aspx.

- 11.Malin JL, Schneider EC, Epstein AM, et al. Results of the National Initiative for Cancer Care Quality: how can we improve the quality of cancer care in the United States? J Clin Oncol. 2006 Feb 1;24:626–34. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.3365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chau I, Norman AR, Cunningham D, et al. A randomised comparison between 6 months of bolus fluorouracil/leucovorin and 12 weeks of protracted venous infusion fluorouracil as adjuvant treatment in colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2005 Apr;16:549–57. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hershman D, Hall MJ, Wang X, et al. Timing of adjuvant chemotherapy initiation after surgery for stage III colon cancer. Cancer. 2006 Dec 1;107:2581–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Des Guetz G, Nicolas P, Perret GY, et al. Does delaying adjuvant chemotherapy after curative surgery for colorectal cancer impair survival? A meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2010 Apr;46:1049–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bilimoria KY, Stewart AK, Winchester DP, Ko CY. The National Cancer Data Base: a powerful initiative to improve cancer care in the United States. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008 Mar;15:683–90. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9747-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steele GD, Jr, Winchester DP, Menck HR The National Cancer Data Base. A mechanism for assessment of patient care. Cancer. 1994 Jan 15;73:499–504. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940115)73:2<499::aid-cncr2820730241>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Winchester DP, Stewart AK, Phillips JL, Ward EE. The national cancer data base: past, present, and future. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010 Jan;17:4–7. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0771-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilkinson NW, Yothers G, Lopa S, et al. Long-term survival results of surgery alone versus surgery plus 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin for stage II and stage III colon cancer: pooled analysis of NSABP C-01 through C-05. A baseline from which to compare modern adjuvant trials. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010 Apr;17:959–66. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0881-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Quality Forum. NQF Endorses Additional Cancer Measures. [Accessed January 28, 2014]; http://www.qualityforum.org/News_And_Resources/Press_Releases/2012/NQF_Endorses_Additional_Cancer_Measures.aspx.

- 20.National Quality Forum. Endorsement Summaries. [Accessed January 28, 2014]; http://www.qualityforum.org/News_And_Resources/Endorsement_Summaries/Endorsement_Summaries.aspx.

- 21.Merkow RP, Bentrem DJ, Mulcahy MF, et al. Effect of postoperative complications on adjuvant chemotherapy use for stage III colon cancer. Ann Surg. 2013 Dec;258:847–53. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shea AM, Curtis LH, Hammill BG, et al. Association between the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 and patient wait times and travel distance for chemotherapy. JAMA. 2008 Jul 9;300:189–96. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang J, Yu KF. What's the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. JAMA. 1998 Nov 18;280:1690–1. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.19.1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu CY, Xing Y, Cormier JN, Chang GJ. Assessing the utility of cancer-registry-processed cause of death in calculating cancer-specific survival. Cancer. 2013 May 15;119:1900–7. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ambler G, Omar RZ, Royston P. A comparison of imputation techniques for handling missing predictor values in a risk model with a binary outcome. Stat Methods Med Res. 2007 Jun;16:277–98. doi: 10.1177/0962280206074466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giorgi R, Belot A, Gaudart J, Launoy G. The performance of multiple imputation for missing covariate data within the context of regression relative survival analysis. Stat Med. 2008 Dec 30;27:6310–31. doi: 10.1002/sim.3476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Quality Forum. Membership in NQF. [Accessed 2013, November 23]; http://www.qualityforum.org/Membership/Membership_in_NQF.aspx.

- 28.National Quality Forum. 2012 NQF Report to Congress. [Accessed November 23, 2013]; http://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2012/03/2012_NQF_Report_to_Congress.aspx.

- 29.Panzer RJ, Gitomer RS, Greene WH, et al. Increasing demands for quality measurement. JAMA. 2013 Nov 13;310:1971–80. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.282047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cohen ME, Bilimoria KY, Ko CY, et al. Variability in length of stay after colorectal surgery: assessment of 182 hospitals in the national surgical quality improvement program. Ann Surg. 2009 Dec;250:901–7. doi: 10.1097/sla.0b013e3181b2a948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hendren S, Birkmeyer JD, Yin H, et al. Surgical complications are associated with omission of chemotherapy for stage III colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010 Dec;53:1587–93. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181f2f202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van der Geest LG, Portielje JE, Wouters MW, et al. Complicated postoperative recovery increases omission, delay and discontinuation of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with colon cancer stage III. Colorectal Dis. 2013 May 17;15:e582–91. doi: 10.1111/codi.12288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wright JD, Neugut AI, Wilde ET, et al. Physician characteristics and variability of erythropoiesis-stimulating agent use among Medicare patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011 Sep 1;29:3408–18. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.5462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.El Shayeb M, Scarfe A, Yasui Y, Winget M. Reasons physicians do not recommend and patients refuse adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III colon cancer: a population based chart review. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:269. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bilimoria KY, Bentrem DJ, Stewart AK, et al. Comparison of commission on cancer-approved and -nonapproved hospitals in the United States: implications for studies that use the National Cancer Data Base. J Clin Oncol. 2009 Sep 1;27:4177–81. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.7018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lerro CC, Robbins AS, Phillips JL, Stewart AK. Comparison of cases captured in the national cancer data base with those in population-based central cancer registries. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013 Jun;20:1759–65. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-2901-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]