Abstract

Xanthomonas citri pv. citri strain 306 (Xcc306), a causative agent of citrus canker, produces endoxylanases that catalyze the depolymerization of cell wall-associated xylans. In the sequenced genomes of all plant-pathogenic xanthomonads, genes encoding xylanolytic enzymes are clustered in three adjacent operons. In Xcc306, these consecutive operons contain genes encoding the glycoside hydrolase family 10 (GH10) endoxylanases Xyn10A and Xyn10C, the agu67 gene, encoding a GH67 α-glucuronidase (Agu67), the xyn43E gene, encoding a putative GH43 α-l-arabinofuranosidase, and the xyn43F gene, encoding a putative β-xylosidase. Recombinant Xyn10A and Xyn10C convert polymeric 4-O-methylglucuronoxylan (MeGXn) to oligoxylosides methylglucuronoxylotriose (MeGX3), xylotriose (X3), and xylobiose (X2). Xcc306 completely utilizes MeGXn predigested with Xyn10A or Xyn10C but shows little utilization of MeGXn. Xcc306 with a deletion in the gene encoding α-glucuronidase (Xcc306 Δagu67) will not utilize MeGX3 for growth, demonstrating the role of Agu67 in the complete utilization of GH10-digested MeGXn. Preferential growth on oligoxylosides compared to growth on polymeric MeGXn indicates that GH10 xylanases, either secreted by Xcc306 in planta or produced by the plant host, generate oligoxylosides that are processed by Xyn10 xylanases and Agu67 residing in the periplasm. Coordinate induction by oligoxylosides of xyn10, agu67, cirA, the tonB receptor, and other genes within these three operons indicates that they constitute a regulon that is responsive to the oligoxylosides generated by the action of Xcc306 GH10 xylanases on MeGXn. The combined expression of genes in this regulon may allow scavenging of oligoxylosides derived from cell wall deconstruction, thereby contributing to the tissue colonization and/or survival of Xcc306 and, ultimately, to plant disease.

INTRODUCTION

Xylanolytic bacteria have been well studied with respect to the enzymes that catalyze the depolymerization of methylglucuronoxylans (MeGXn) and methylglucuronoarabinoxylans (MeGAXn), the predominant polysaccharides comprising hemicellulose in dicots and monocots, respectively (1, 2). As components of plant cell walls, these polysaccharides serve functions important to plant growth. Characterization of the genes and their encoded enzymes that contribute to both the depolymerization of MeGXn and MeGAXn and the utilization of the products of depolymerization have led to definitions of systems that function for both the extracellular depolymerization and the assimilation of oligosaccharides, followed by the intracellular processing of these oligosaccharides. Systems involving the depolymerization of xylans with a secreted glycoside hydrolase family 10 (GH10) endoxylanase, transporters for assimilation of oligoxylosides, and intracellular glycohydrolases, including a GH67 α-glucuronidase, are notably efficient in the utilization of MeGXn and MeGAXn (3–6).

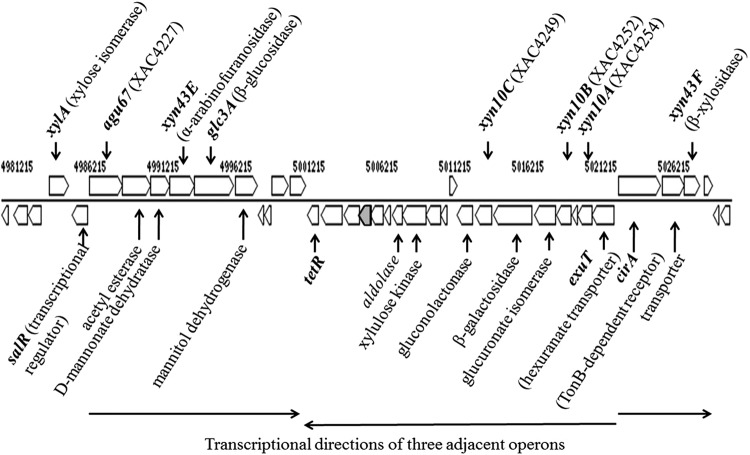

All plant-pathogenic Xanthomonas spp. for which genome sequence data are available contain genes orthologous to those comprising xylan utilization gene clusters encoding GH10 endoxylanases and a single gene encoding a GH67 α-glucuronidase (7). The arrangement and content of genes within these operons differentiate these species into three groups. Members of the first group include Xanthomonas citri pv. citri strain 306 (Xcc306), Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria, and Xanthomonas perforans, in which all three endoxylanase genes (xyn10A, xyn10B, and xyn10C) are present, along with genes further downstream of this operon encoding an additional 10 proteins. Members of the second group include X. campestris pv. campestris, Xanthomonas vesicatoria, and Xanthomonas gardneri, in which two of the three endoxylanase genes are present (xyn10A and xyn10C) and in which the downstream genes encoding additional proteins are absent. A third group includes Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae, in which a different set of two endoxylanase genes are present (xyn10A and xyn10B) and in which the beta-galactosidase and gluconolactonase genes flanking xyn10C in other groups are incomplete. However, the genetic organization of the α-glucuronidase operon is conserved across these species, and of all other phytopathogenic bacteria for which genome sequences are available, only these species have the combination of GH10 xylanases and GH67 α-glucuronidases. The genomic organization of the xylan utilization cluster for Xcc306 is shown in Fig. 1.

FIG 1.

Cassette of operons with xylan deconstruction genes in Xcc306. The arrows identify sequences that are transcribed from a promoter to generate a polycistronic message.

GH10 endoxylanases of phytopathogenic species of Xanthomonas have been implicated in cell wall deconstruction of plant hosts and may contribute to plant disease (8, 9). The GH10/GH67 system has been genetically defined in X. campestris pv. campestris and shown to allow the depolymerization and efficient utilization of oligosaccharides (8). The present study is concerned with the role of endoxylanases and related enzymes collectively involved in xylan utilization for the growth of Xcc306 and their potential contribution to pathogenicity. Xcc306 shows a preferred utilization of the products of MeGXn depolymerization rather than of polymeric MeGXn and the coinduction of expression of genes encoding xylanases and neighboring genes by the products that support the growth of Xcc306. With the predominant localization of the xylanase activity in the periplasm, the extracellular processing of xylan appears to be a limiting step for the growth of Xcc306.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Growth studies of Xcc306.

Growth studies of X. citri pv. citri strain 306 (Xcc306) were performed by inoculating equal cell numbers grown in nutrient broth to exponential phase into the different media as specified below. The cultures were incubated at 28°C with shaking at 200 rpm. Cell growth over time was monitored by measuring optical density at 600 nm (OD600), and aliquots of culture were removed when necessary for further analyses. From studies on the interaction of X. campestris pv. vesicatoria with its host tomato plant, two similar apoplast-mimicking media, XVM1 and XVM2 (10), which variably induce hrp gene expression, were constituted. XVM2m is a modified recipe of the XVM2 minimal medium and does not contain the carbohydrate carbon sources sucrose and fructose [20 mM NaCl, 10 mM (NH4)2SO4, 1 mM CaCl2, 0.01 mM FeSO4, 5 mM MgSO4, 0.16 mM KH2PO4, 0.32 mM K2HPO4, 0.03% Casamino Acids, pH 6.7]. Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) to detect substrate processing was performed as previously described (3).

Bacterial strains.

Cultures of Xcc306, also known as Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri strain 306, were routinely maintained on nutrient broth agar plates as previously described (11). Construction of Xcc306 Δagu67 by mutagenesis was performed by double displacement of a portion of the agu67 gene (XAC4227) as previously described (12). A 2,469-bp PCR product encompassing the agu67 gene, obtained by using primers 4227F (5′-CTCTTCAAATGCGTGCAAAAGCTGC) and 4227R (5′-GTCCTGAAAAATGGGATGCAGTAGC), was cloned into the vector pGEM-T Easy. The internal BamHI fragment of 1,092 bases in the agu67 coding sequence, which includes the bases encoding the catalytic residues D395 and E423, was deleted from the cloned gene. The partially deleted agu67 gene was then cloned into the suicide vector pOK1 and was transformed into Xcc306 to eventually obtain the mutant strain Xcc306 Δagu67. DNA sequencing of an amplicon generated by PCR confirmed the partial deletion of the agu67 gene.

Enzyme assays.

Xylanase activities with MeGXn as the substrate were determined with the Nelson reducing sugar assay to measure glycosidic bond cleavage (13). Time course assays (30 min) were performed to identify velocities representing initial velocities that could be used for estimation of kinetic parameters. The relationship between enzyme concentration and activity was determined to quantify a condition for the estimation of maximum velocity and kcat. Xylanase was also assayed by the conversion of the fluorogenic substrate 6,8-difluoro-4-methylumbelliferyl β-d-xylobioside (DiFMUX2) to 6,8-difluoro-4-methylumbelliferone (DiFMU) (14, 15) using an EnzChek Ultra xylanase assay kit (catalog no. E33650; Molecular Probes, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). One hundred-microliter reaction mixtures containing 50 μg/ml substrate and various amounts of test cell fractions in 50 mM sodium acetate, pH 6.0, were performed in 96-well plates. Reaction mixtures were incubated at room temperature for up to 2 h, and readings were taken at an excitation of 360 nm and an emission of 460 nm with a fluorescence plate reader (Synergy HT reader; Bio-Tek, Winooski, VT).

Alkaline phosphatase assays, performed according to the protocol of Bessey et al. (16), were carried out in 96-well plates with a final reaction volume of 250 μl. Ten microliters of Xcc306 cell fractions, obtained from exponential culture assayed for xylanase as described below, were added to 190 μl of substrate buffer containing 10 mM p-nitrophenylphosphate, 2.5 mM glycine, 0.05 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KH2PO4-K2HPO4, adjusted to pH 10.5 with 1 N NaOH. Reaction mixtures were incubated for 30 min at 37°C and terminated by adding 50 μl of 0.085 N NaOH, and the amount of p-nitrophenol released was measured at 405 nm. Standard curves of p-nitrophenol (1 to 10 nmol) in substrate buffer were constructed to quantify p-nitrophenol release from the enzyme reactions. Specific activity was expressed as nmol p-nitrophenol released per min per OD600 of culture.

Determination of xylanase activities in cell fractions.

Twenty-five-milliliter samples of Xcc306 cultures at late log phase were harvested. Cultures were subjected to centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant (culture medium), to which was added 100 μl proteinase inhibitor (Halt protease inhibitor; Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL), was concentrated to 2 ml or less by filtration through regenerated cellulose membranes with a 3-kDa cutoff (Amicon Ultra filters; Millipore, Billerica, MA). The cell pellets were washed twice with 10 ml 50 mM sodium acetate, pH 6.5, and resuspended in 2 ml of the acetate buffer. The resuspended cells were disrupted by two passages through a French pressure cell at 16,000 lb/in2. Cell membranes were pelleted at 13,000 × g for 40 min at 4°C, and supernatants, designated cell fractions, were tested for xylanase activity.

Determination of xylanase activities in subcellular fractions.

Five-milliliter cultures of Xcc306 were grown to late log phase in XVM2m with additional carbohydrates as specified in the figure legends. Cell fractionation was performed according to the method of Hu et al. (17). Cultures were subjected to centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 10 min and cells harvested. The supernatants were collected as the extracellular fractions. The cell pellets were rinsed with 10 mM MgCl2 and resuspended in 30 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1.0 mM EDTA, 20% (vol/vol) sucrose, 200 μg/ml lysozyme and incubated for 2 h on ice to lyse the outer membrane. These cell mixtures were subjected to centrifugation at 21,000 × g for 10 min to obtain the periplasmic fractions in the supernatants and the spheroplasts in the pellets. The pellets were resuspended in 0.25 ml 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, passed 50 times through a syringe fitted to a 23-gauge needle, and centrifuged at 21,000 × g for 15 min, and the supernatants were collected as the cytoplasmic fractions. All fractions were passed through a 10-kDa cutoff filter (Micron Ultracel YM-10; Millipore) to remove residual cell debris. Fractions were concentrated to equal volumes for xylanase assays.

RNA isolation.

Bacteria grown in nutrient broth (NB) to an OD600 of 0.3 with shaking at 200 rpm were inoculated into different media at a 1:15 ratio to a starting OD600 of 0.02. The bacterial cultures were incubated with shaking at 200 rpm to exponential phase, and 10 ml of each culture was collected. The bacterial samples were treated with RNAprotect reagent (Qiagen, Germantown, MD) prior to RNA extraction. Cultures were subjected to centrifugation, and cell pellets were treated with lysozyme (200 μl, 15 mg/ml) and proteinase K (10 μl, 20 mg/ml) for 10 min. RNA extractions were performed using the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen). Genomic DNA was removed from RNA samples by treatment with a Turbo DNA-free kit (Ambion, Life Technologies).

qRT-PCR.

Genes from the xylan utilization cassette were chosen for expression studies with the gyrB and atpD genes, which were also tested to serve as control genes for expression outside the cassette. The primers detailed in Table 1 were designed using Primer3 software (18) and the nucleotide sequence of the Xcc306 genome. A one-step quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed with a Bio-Rad CFX96 system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) using an iScript one-step RT-PCR kit with SYBR green (Bio-Rad). The total volume of the one-step qRT-PCR mixture was 20 μl and contained 2× SYBR green RT-PCR mix (10 μl), 10 μM gene-specific primers (0.6 μl), iScript reverse transcriptase (0.4 μl), and 200 ng of the RNA template. The reaction mixtures were incubated at 50°C for 10 min and at 95°C for 5 min and then subjected to 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 s and 60°C for 30 s. Melting curve analyses were performed to verify the specificity and identities of the PCR products. Duplicate reactions were performed in each study.

TABLE 1.

Primers used in this study

| Gene locus | Gene name | Protein name (function) | Primer name (nucleotide sequence) |

|---|---|---|---|

| XAC0004 | gyrB | GyrB (DNA gyrase subunit B) | F1472 (ACGAGTACAACCCGGACAAG) |

| R1585 (GCATCTGCCGGTAGAAGAAG) | |||

| XAC3649 | atpD | ATP-D (ATP synthase, beta subunit) | F464 (CCGTCAACATGATGGAACTG) |

| R600 (CTTGTCCAGGACGTTGGAGT) | |||

| XAC4225 | xylA | XylA (xylose isomerase) | F367 (TACGAGAGCAACCTCAAGCA) |

| R490 (TCGAGGCACCATTCATGTAG) | |||

| XAC4226 | salR | SalR (sal operon transcriptional repressor) | F546 (AGCCAAAGAGATCACCGAAC) |

| R730 (GGCCGGATTTGTAGGTGTAA) | |||

| XAC4227 | agu67 | Agu67 (α-glucuronidase GH67) | F444 (CAGCGATATCGGGGTGTTAT) |

| R600 (ATAGCCACGTTCCACCAGAC) | |||

| XAC4230 | xyn43E | Xyn43E (arabinofuranosidase GH43) | F1050 (ACAGCCGATTCCTTACATCG) |

| R1154 (GTGTGATCGAAATCGTCGTG) | |||

| XAC4237 | tetR | TetR (transcriptional regulator) | F89 (CGACCGAGACCTACGAACAT) |

| R244 (CGGACAACAGCGCATATTTA) | |||

| XAC4249 | xyn10C | Xyn10C (endoxylanase GH10) | F328 (ACACCGGAGTGGTTCTTCAC) |

| R494 (GAACGGTAACTGCCGTCTTC) | |||

| XAC4252 | xyn10B | Xyn10B (endoxylanase GH10) | F40 (GAAACTCCGTTATCCGCTCA) |

| R158 (CTTGCCGTGGGCTGTAGG) | |||

| XAC4254 | xyn10A | Xyn10A (endoxylanase GH10) | F134 (TTGCGCAGTACTGGAACAAG) |

| R284 (ACCATGACATGCATCTGGAA) | |||

| XAC4255 | exuT | ExuT (exuronate transporter) | F794 (CCGCAGAACTGGCGTATATC) |

| R946 (GCAGCCAGAACAGGAAGAAC) | |||

| XAC4256 | cirA | TBDR (tonB-dependent receptor) | F122 (ACCGACGTAGCATCCAGTTC) |

| R222 (ATTCATGTCCGGAAACTTGC) | |||

| XAC4258 | xyn43F | Xyn43F (β-xylosidase GH43) | F803 (CCTACGGCCCGTTTACCTAT) |

| R921 (GAGCACGCTGTCGTGATAGA) |

Real-time quantitative-PCR data were analyzed by using the absolute quantification method as described in the real-time PCR application guide of Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc. (19). Briefly, a known amount of Xcc306 genomic DNA was amplified by PCR using primers designed to amplify a segment of 200 to 250 bp of the genes of interest. Tenfold dilutions ranging from 102 to 107 genomic molecules were added as the template to the reaction mixtures, and the threshold cycle (CT) values of the detection of products were plotted against the logarithmic values of the initial number of copies of template added. Amplification efficiency (E) was calculated from the slope of the curve using the formulae E = 10−1/slope and % E = (E – 1) × 100%. Several sets of primer pairs for each gene under study were designed and evaluated until 90 to 105% efficiency was achieved. A standard curve of 90 to 100% efficiency was thus generated for each optimal primer pair for each gene. The equation of linear regression, y = mx + b, where y is the CT value, m is the slope of the graph, x is the logarithmic value of the number of molecules of RNA, and b is the y intercept, was used to calculate the number of molecules of RNA present in the sample.

RESULTS

Growth of Xcc306 in sweetgum xylan with and without sucrose-fructose.

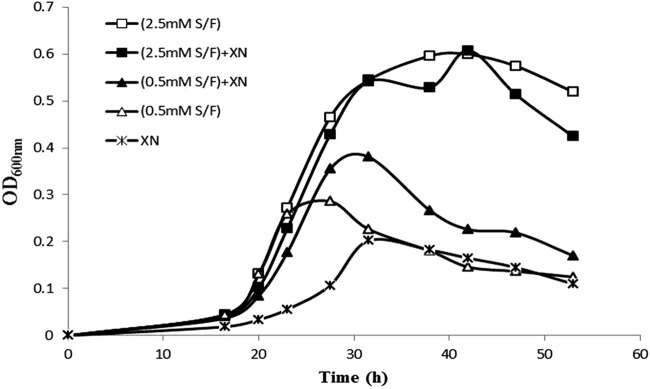

Bioinformatic studies of the sequenced genome of Xcc306 identified the presence of xylan utilization genes in Xcc306 and led us to investigate the growth characteristics of Xcc306 in sweetgum xylan. Purified methylglucuronoxylan (MeGXn) from sweetgum wood was selected as a source of xylan, as it has been well defined in previous studies to be comprised almost exclusively of β-1,4-linked xylose residues variably modified with 4-O-methylglucuronate residues via α-1,2 linkages at a ratio of methylglucuronate to xylose of 1:6 to 1:7, with an estimated degree of polymerization of approximately 250 (3, 20). Acetyl groups were removed by KOH treatment during the preparation of MeGXn. XVM2 medium was chosen because it was previously constituted for the investigation of hrp gene expression; however, in this study, the sucrose and fructose contents were reduced from 10 mM to 2.5 mM and 0.5 mM to discern growth attributed to xylan utilization. Figure 2 shows representative results from several experiments. When xylan polymer, MeGXn, is the sole carbon source, Xcc306 grows poorly, attaining an OD600 of 0.20 at 31 h (Fig. 2). Several hours of lag time preceded exponential growth in xylan compared with the time to exponential growth in media which included sucrose and fructose. However, while the contribution to growth of MeGXn as the sole carbon source was not discernible in media with 2.5 mM sucrose and 2.5 mM fructose (Fig. 2, ■ and □ traces), an increase in growth of 0.1 OD600 unit (Fig. 2, an OD600 of 0.38 at 31 h [▲] minus an OD600 of 0.28 at 27 h [▵]) was obtained in media with 0.5 mM sucrose and fructose.

FIG 2.

Growth of Xcc306 in sweetgum xylan with and without sucrose-fructose (S/F). Equal aliquots of an Xcc306 culture were inoculated into 6 culture tubes, (each) containing 4 ml of medium. All 6 cultures contained XVM2m with or without carbohydrates. □, 2.5 mM (each) sucrose and fructose; ■, 2.5 mM (each) sucrose and fructose and 0.25% sweetgum MeGXn (XN); ▲, 0.5 mM (each) sucrose and fructose and 0.25% sweetgum MeGXn; ◇, 0.5 mM (each) sucrose and fructose; *, 0.25% sweetgum MeGXn. Cultures were incubated at 28°C with shaking at 200 rpm.

Intracellular localization of xylanase activity.

To find the cellular locations of these enzymes, cells were grown in media with and without xylan and tested for xylanase activity in the media and in crude cell fractions. The results are shown in Table 2. Media were concentrated to equal the volume of resuspended cell fractions, and these preparations were tested for xylanase activity in fluorescence-based assays monitored for 2 h. Xylanase activities between 0.12 and 0.17 U/mg were found exclusively in the cell fractions (Table 2) and not in any of the three concentrated culture media, in all of which the xylanase activities were less than 10−4 U/mg. Specific activity (U/mg) is defined as the number of micromoles of product per minute per milligram of protein for cytoplasmic preparations or purified cloned enzyme. By the fluorescent assay, cloned Xyn10A activity is 19.7 U/mg and Xyn10C activity is 1.3 U/mg. The specific activities of the purified cloned enzymes XynA2 from Paenibacillus sp. strain JDR2 and Xyn10A and Xyn10C from Xcc306 are also included in Table 2 for comparison.

TABLE 2.

Xylanase activities in cell fractions and recombinant xylanasesa

| CF or rXyn | Medium composition or rXyn source(s) | Sp actb |

|---|---|---|

| CF 1 | 2.5 mM each S and F | 0.126 |

| CF 2 | 0.5 mM each S and F, 0.2% sweetgum xylan | 0.174 |

| CF 3 | 0.2% sweetgum xylan | 0.150 |

| Xyn10A | Xcc306 | 19.7 |

| Xyn10C | Xcc306 | 1.3 |

| XynA2 | Paenibacillus sp. JDR2 | 21.6 |

Cell cytoplasmic fractions (CF) were prepared from cultures of Xcc306 grown on XVM2m containing the indicated carbohydrate source(s) (S, sucrose; F, fructose). Pure recombinant xylanases (rXyn) were produced in Escherichia coli from the xyn10A and xyn10C genes from Xcc306 or the xynA2 gene from Paenibacillus sp. JDR2.

Specific activities are given as units (μmol product/min) per mg protein as determined by formation of the fluorescent product DiFMU.

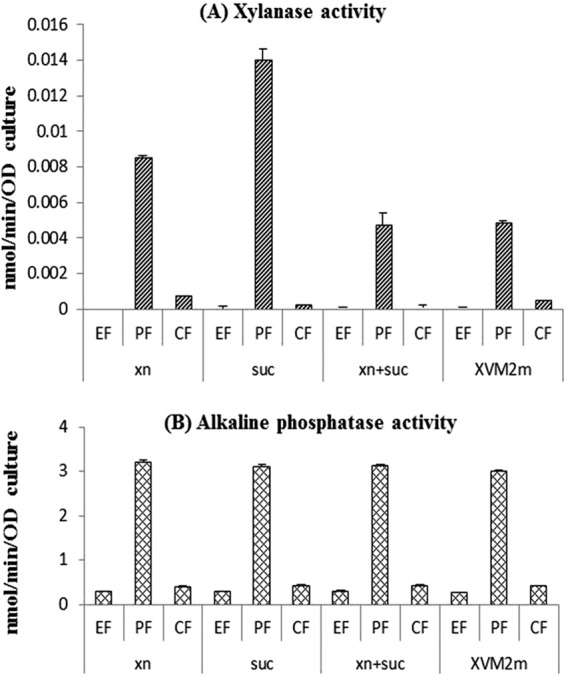

To further investigate the subcellular localization of xylanase activities, Xcc306 cells were fractionated into periplasmic and cytoplasmic fractions. The results, shown in Fig. 3, indicate that the majority of activities are located in the periplasmic fractions. To verify the cell fractionation procedure, activities of a periplasmic enzyme, alkaline phosphatase (21), were also determined. Attempts to detect xylanase activities secreted by Xcc306 colonies grown on agar plates with xylan were not successful. Plates containing 0.5% oat spelt xylan in XVM2m overlaid with 500 μl of 50 mM each sucrose and fructose did not elicit, after 4 days, any halo formation surrounding these colonies as a measure of xylan hydrolysis and xylanase activities, in contrast to the distinct and plentiful halo formation by the control bacterium Paenibacillus sp. JDR2 (data not shown).

FIG 3.

Xylanase activities in subcellular fractions. Xylanase activities were measured by the fluorescent assay using DiFMUX2 as the substrate (A), and alkaline phosphatase activities were measured with p-nitrophenyl phosphate (B) as described in Materials and Methods. The culture media were 0.2% sweetgum xylan in XVM2m (xn), 2.5 mM sucrose in XVM2m (suc), 0.2% sweetgum xylan and 2.5 mM sucrose in XVM2m (xn+suc), and XVM2m. The subculture fractions were the extracellular fraction (EF), periplasmic fraction (PF), and cytoplasmic fraction (CF). Since lysozyme was added to prepare the periplasmic fractions, enzymatic activity units are expressed as per OD600 of cell cultures instead of per protein concentration. Error bars represent error values from duplicate cultures.

Growth promotion by oligoxylosides derived from xylan.

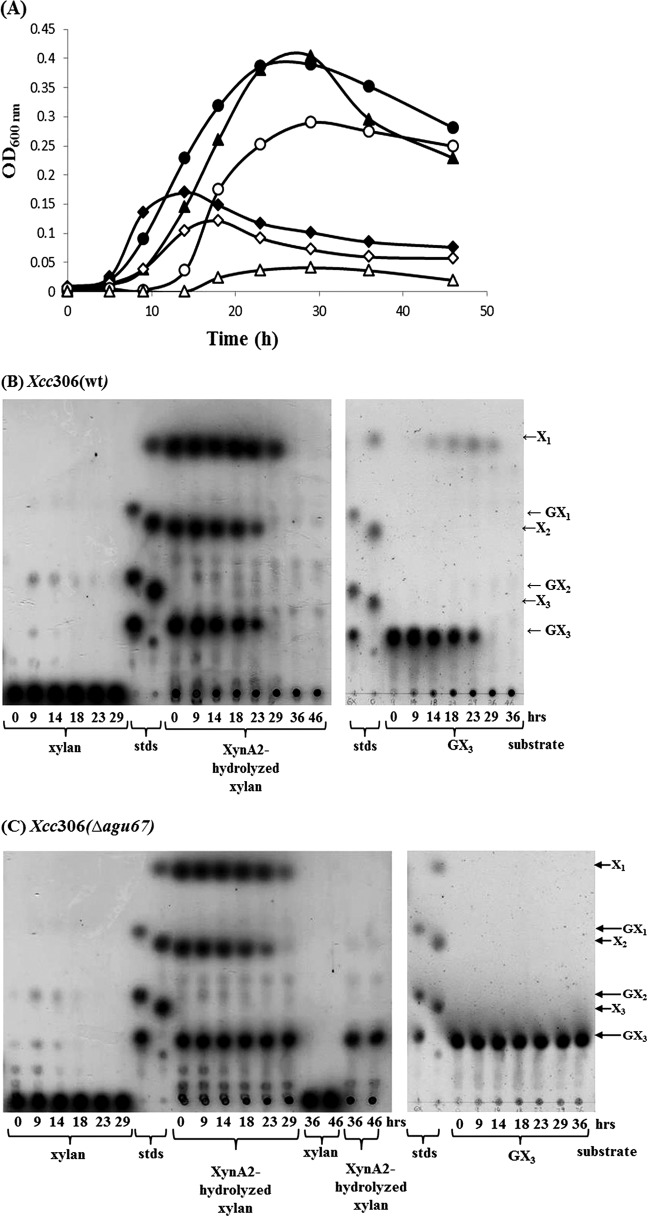

To determine the role of GH10 xylanases and GH67 α-glucuronidase in Xcc306 growth, substrate utilization and growth characteristics were determined for both wild-type Xcc306 and the mutant strain of Xcc306 in which the α-glucuronidase gene is deleted (Fig. 4). XynA2 is a GH10 β-1,4 endoxylanase cloned from Paenibacillus sp. JDR2 that has been well defined with respect to activity and product formation (15). In media with xylan, both Xcc306 and Xcc306 Δagu67 showed moderate growth, to OD600s of 0.15 and 0.11, respectively, utilizing the small amount of the oligoxylosides presumably generated by secreted xylanase (Fig. 4B and C). In media containing XynA2-hydrolyzed sweetgum xylan, Xcc306 and Xcc306 Δagu67 grew well, reaching OD600s of 0.40 and 0.30, respectively (Fig. 4B and C), with further growth probably limited by the complete utilization of the oligoxylosides in the media. MeGXn (0.2%) supported exponential growth for 14 to 16 h, while XynA2-hydrolyzed MeGXn hydrolyzed by GH10 XynA2 sustained growth to 23 to 29 h. Each of the three major sources of oligoxylosides produced by hydrolysis of xylan, methylglucuronoxylotriose (MeGX3), xylobiose (X2), and xylose (X1), was consumed over the 46 h of growth (Fig. 4B and C), while the majority of the nonhydrolyzed polymeric MeGXn initially present in the media was not utilized.

FIG 4.

Growth of Xcc306 (wild type [wt]) and Xcc306 Δagu67 in XVM2m containing sweetgum MeGXn or depolymerized MeGXn products. (A) Two-milliliter samples of culture medium containing XVM2m and 0.2% sweetgum MeGXn (◆ and ◇), XynA2-hydrolyzed 0.2% sweetgum MeGXn (● and ○), or 0.2% (3.3 mM) MeGX3 (▲ and ▵) were inoculated with an aliquot of either Xcc306 (◆, ●, ▲) or Xcc306Δagu67 (◇, ○, ▵) in nutrient broth at an OD600 of 0.01. Cell cultures of Xcc306 (B) and Xcc306 Δagu67 (C) were incubated at 28°C with rotation at 200 rpm. Media taken at the times (in hours) after initiation of incubation were analyzed by thin-layer chromatography (TLC). Xylan, cultures with 0.2% sweetgum MeGXn; stds, MeGX1-MeGX3 (10 nmol each) and X1-X3 (10 nmol each); XynA2-hydrolyzed xylan, cultures with 0.2% sweetgum xylan digested by XynA2; GX3, cultures with 0.2% (3.3 mM) MeGX3. Twelve microliters of the medium of each culture was spotted.

In media containing MeGX3, Xcc306 consumed this tetrasaccharide and grew well, but Xcc306 Δagu67 did not utilize MeGX3 for growth (Fig. 4A). When Xcc306 metabolized MeGX3, neither xylotriose (X3) nor X2 was detected in the media (Fig. 4B), indicating that MeGX3 was imported into the periplasm intact and hydrolyzed there or intracellularly. During growth of both the wild type and the Δagu67 mutant of Xcc306, free X1 began to appear at late log phase of growth and was very slowly although completely consumed (Fig. 4B and C). Other experiments on the growth of Xcc306 in X1 alone also showed much slower substrate consumption and cell growth than when it was grown in MeGX3 (data not shown). Xcc306 Δagu67 containing a plasmid with the complete agu67 gene restored the growth pattern for Xcc306 (Fig. 4A; unpublished data).

To determine whether Xyn10A or Xyn10C-hydrolyzed xylan would also support Xcc306 growth, sweetgum xylan was digested by purified Xyn10A or Xyn10C and added to XVM2m. Either Xcc306 or Xcc306 Δagu67 was inoculated into these media. Both of these strains grew well, with similar growth characteristics in XynA2-hydrolyzed xylan, as shown in Fig. 4. All of the oligoxyloside products generated by either XynA2, Xyn10A, or Xyn10C hydrolysis were consumed by Xcc306, indicating that the assimilation and metabolism of the products of the xylanases were not rate-limiting steps (results not shown).

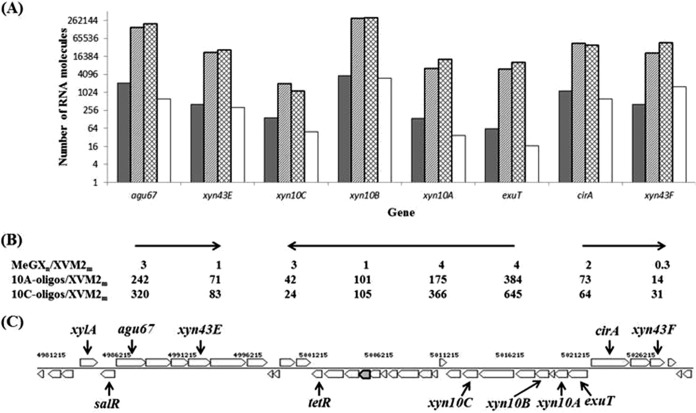

Coinduction and expression of xylan utilization genes.

Real-time RT-PCR was performed to determine the influence on the expression of genes in the cassette illustrated in Fig. 1 by growth in MeGXn and oligoxylosides isolated from hydrolyzed MeGXn. As shown in Fig. 5, expression of genes in the three opposing operons was induced by growth in sweetgum MeGXn, oligoxylosides from Xyn10A-hydrolyzed MeGXn, or oligoxylosides from Xyn10C-hydrolyzed MeGXn (Fig. 5A). Genes encoding glycoside hydrolase enzymes located in the upstream operon, agu67 and xyn43E, and those located in the downstream operon, xyn10A, xyn10B, and xyn10C, were induced 1- to 4-fold when Xcc306 was grown in MeGXn and 24- to 366-fold when Xcc306 was grown in Xyn10A hydrolysates or Xyn10C hydrolysates (Fig. 5B). Gene xyn43F, encoding a β-xylosidase utilized in xylan depolymerization and positioned peripheral to these two operons, was induced 14- or 31-fold by a Xyn10A- or Xyn10C-derived hydrolysate, respectively, although there was a one-third reduction when the strain was grown in MeGXn. Gene cirA, which encodes the TonB-dependent receptor, was induced 2-fold by MeGXn and 64- to 73-fold by the hydrolysates. Expression induction of the collection of genes probed within each operon decreases in the direction of transcription in the three operons that were analyzed, consistent with the effect of polarity in the transcription process (Fig. 5B). The genes gyrB and atpD, located outside the cassette and with functions unrelated to xylan utilization, are not induced (results not shown) by either xylan or its hydrolysates. The consensus of this and repeated experiments is that genes in this cassette are induced when Xcc306 is grown in media supplemented with xylan or oligoxylosides isolated from hydrolyzed xylan. The induction of expression is many times greater by oligoxylosides derived from xylan than by the xylan polymer; the extents of induction by oligoxylosides from Xyn10A hydrolysis and by Xyn10C hydrolysis of MeGXn are similar, and these responses are synchronous among the genes of the cassettes investigated.

FIG 5.

Expression of genes in the xylan utilization cassette of Xcc306. (A) Relative numbers of mRNA molecules expressed when Xcc306 is grown in MeGXn (dark-gray columns), in oligoxyloside mixtures of sweetgum MeGXn hydrolyzed by Xyn10A (light-gray columns), and by Xyn10C (hatched columns) and XVM2m (unfilled columns). (B) Ratios of mRNA molecules expressed by selected genes in Xcc306 cells grown in MeGXn, in Xyn10A, and in Xyn10C oligoxylosides (oligos) relative to the ratio in Xcc306 cells grown in XVM2m. Horizontal arrows depict transcriptional directions of gene clusters. (C) Diagram of the xylan utilization gene cassette in Xcc306.

DISCUSSION

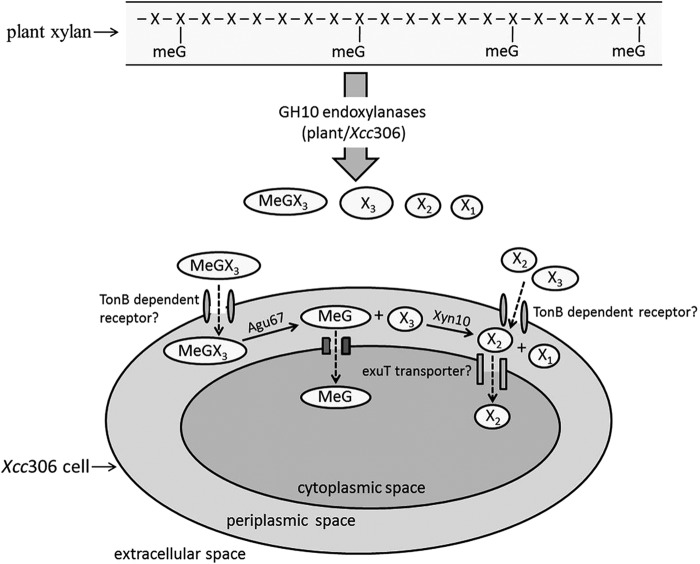

A model for the depolymerization and uptake of xylan is presented (Fig. 6). When Xcc306 grows in the presence of xylan, it depolymerizes small amounts of xylan polymer to produce oligosaccharides for limited growth. Supplementing the amounts of oligoxylosides in the medium by supplying breakdown products of xylan by GH10 endoxylanases allows robust growth of Xcc306. MeGX3, a breakdown product, is transported, possibly via the TonB-dependent receptor, to the periplasm, where the 4-O-methylglucuronyl group is released from the nonreducing terminal xylose by a membrane-bound GH67 α-glucuronidase enzyme located in the periplasm. Previous studies of Cellvibrio japonicus (Pseudomonas cellulosa) identified this enzyme to be associated with cellular membranes (22), and bacterial GH67 α-glucuronidases are commonly found as membrane-associated enzymes. In the periplasm, the released xylotriose products are processed by the endoxylanases Xyn10 to xylobiose. Conversion of xylotriose may also occur via the removal of the xylose residue from the nonreducing end by GH43 β-xylosidases, such as the protein product of the gene at locus XAC4183, as annotated by Integrated Microbial Genomes (IMG). Xylobiose and possibly xylotriose may be imported into the cytoplasm for further processing and metabolism. The transporter molecules involved in this trafficking have not been identified, and their hypothetical specificities and locations are included in the model.

FIG 6.

Model of xylan depolymerization and assimilation by Xcc306. The extracellular depolymerization of the methylglucuronoxylan (MeGXn) generates predominantly MeGX3, X3, and X2, as well as minor amounts of xylose, the ratios of which depend upon the frequency of the MeG substitutions. Oligoxylosides may be imported into the periplasm via TonB-dependent receptors and further processed within the confined periplasmic space prior to assimilation and metabolism.

We note that both xylanases Xyn10A and Xyn10C have a signal peptide which would translocate them to the periplasm during synthesis. However, we do not rule out the possibility that these enzymes are secreted to the extracellular space when Xcc306 grows on citrus tissues, perhaps in response to a plant signal (23). Two sources of the oligoxylosides for Xcc306 growth can be considered: one is xylan depolymerization by secreted Xcc306 xylanases, and the other is depolymerization by the host plant's xylanases.

In the first instance, we observe from our experimental results that Xcc306 xylanases are not found in significant levels in the medium (Fig. 3) and are therefore unavailable to depolymerize extracellular xylan. However, growth of Xcc306 in planta may provide secretion signals for these xylanases. This study shows induction of expression of genes encoding glycoside hydrolases, the transporter, and TonB-dependent receptor proteins by xylan and xylan hydrolysates. Dejean et al. (8) reported similar expression induction by xylo-oligosaccharide substrates in their investigation of the homologous genes in X. campestris pv. campestris. In the present study, when Xcc306 was grown in oligosaccharides derived from Xyn10A hydrolysate of xylan, increases in the expression of the xyn10A, xyn10B, xyn10C, and agu67 genes relative to their expression in XVM2m media were 175-, 101-, 42-, and 242-fold, respectively, and the increase in the expression of the cirA gene was 73-fold (Fig. 5). When X. campestris pv. campestris was grown in xylotriose, the genes xyn10A, xyn10C, and agu67 were induced 5-, 15-, and 25-fold, respectively, relative to their expression when the organism was grown in minimal media, while the TonB-dependent receptor-encoding gene xytB was induced 152-fold (8). However, the results of Dejean et al. (8) indicated an extracellular localization of endoxylanases, while the results of this study indicate their periplasmic localization in Xcc306.

The differing conclusions of xylanase localization may be partially due to the different culture conditions, the enzyme assays used to detect activity, the variable specific activities, and the repertoire of xylanase-encoding genes of the Xanthomonas species under study. Sun et al. (9) and Szczesny et al. (24) investigated the secretion of endoxylanases by the T2SS system and the role of endoxylanases in virulence in Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae PXO99 and Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria 85-10, respectively. Sun et al. (9) described xylanase activity in both the extracellular and periplasmic spaces of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae. Szczesny et al. (24) found the X. campestris pv. vesicatoria ΔxynC mutant to induce less virulence in susceptible pepper plants. However, XynC (locus tag XCV0965) is an endoxylanase in the GH30 family and not in the GH10 family (XCV4355, XCV4358, and XCV4360) in X. campestris pv. vesicatoria. It should be noted that GH30 xylanases generate oligosaccharides that are not assimilated and metabolized without the assistance of another xylanase (1, 25, 26). Xcc306 differs from X. campestris pv. campestris, Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae, and X. campestris pv. vesicatoria in that the corresponding gene in the Xcc306 genome that encodes the endoxylanase GH30 (previously designated GH5) is truncated (7) and therefore inactive. Since the xyn10B gene in Xcc306 does not encode a functional enzyme, xylanase activities expressed by Xcc306 are then solely due to the GH10 enzymes encoded by the genes xyn10A and xyn10C in the above-described cassette. The xynB gene may not encode a functional enzyme, as the NCBI-denoted translation start site results in a protein product without a secretion peptide and thus the xylanase synthesized would be an intracellular protein unable to act on xylan outside the cell or oligoxylosides located in the periplasmic space of the cell (unpublished). The recombinant forms of the Xyn10A and Xyn10C from Xcc306 have been shown to generate MeGX3, X3, and X2 from MeGXn from citrus leaves and sweetgum wood (unpublished) and have recently been structurally defined (27). The coordinate expression of xyn10 genes with the agu67 gene ensures the assimilation of the maximal amount of oligoxylosides for complete metabolism of xylose derived from plant cell walls.

In considering the possible role of plant-derived endoxylanases in the depolymerization process, genes encoding GH10 endoxylanases are present in the Citrus sinensis genome (28; http://citrus.hzau.edu.cn/orange/index.php). A search for endoxylanase-encoding genes in C. sinensis yielded 5 such loci: Cs8g04100.1, Cs8g04110.1, Cs8g02850.1, Cs8g02860.1, and Cs3g16470.1. These putative endoxylanases belong to the GH10 family, and all contain the two requisite glutamate catalytic residues situated 107 to 109 amino acid residues apart (1). Transcriptome sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis (http://citrus.hzau.edu.cn/cgi-bin/orange/gene/Cs8g04110.1) showed that genes encoding four of these five endoxylanases (Cs8g02860.1 being the exception) are expressed abundantly in the leaves and fruit. Inspection of another recently sequenced Xanthomonas host, Solanum lycopersicum (http://mips.helmholtz-muenchen.de/plant/tomato/searchjsp/index.jsp), also uncovered two genes that encode endoxylanases, also of the GH10 family. It had been noted that young citrus trees are more susceptible to Xcc306 infection (29–31). It is possible that growth of young leaves involves the remodeling of xylan's structure (32) by the expression of the host plant's endoxylanases and that this results in a pool of oligoxylosides for uptake and growth of Xcc306.

Genes potentially encoding GH10 xylanases have been found in all of the sequenced genomes of plants, although there are no reports on the properties of plant GH10 xylanases. For GH10 endoxylanases from bacterial and fungal sources, the MeGX3 generated from MeGXn and MeGAXn by a GH10 endoxylanase contains a methylglucuronate that is α-1,2 linked to the nonreducing terminal xylose, a requirement for processing by a GH67 α-glucuronidase to release xylotriose. The combination of the GH10 endoxylanases and the GH67 α-glucuronidases is necessary for the efficient depolymerization and catabolism of MeGXn and MeGAXn (1, 4, 15, 33). The presence of xyn10 and agu67 genes in Xcc306 and all other phytopathogenic xanthomonads supports a role for complete processing and metabolism of MeGXn, including MeGX3, as well as X3 and X2. There may be conditions under which photosynthates are limiting and an efficient xylan utilization system provides a survival advantage. It is noteworthy that this system is not common to other phytopathogenic bacteria. The absence of orthologs of agu67 genes in any of the plant genomes supports a connection between cell wall reconstruction by plant GH10 enzymes and the availability of a preferred substrate for the proliferation of phytopathogenic xanthomonads.

A question arises when the robust growth of Xcc306 on oligoxylosides of depolymerized xylan is contrasted to Xcc306's minimal growth on xylan polymer. What might be the host plant's stimuli that initiate Xcc306 endoxylanase secretion or the pathogenic bacterial signals that promote plant endoxylanase production? Either of these events would result in the accumulation of oligoxyloside nutrients for Xcc306 and allow growth and colonization of the plant by the bacterial pathogen. Perhaps favorable conditions gained cumulatively in the microenvironment of the infected site may help Xcc306 establish an opportunistic and persistent infection in the citrus host. There is a noted absence in the sequenced genomes of any other phytopathogenic bacteria of genes encoding either a GH10 endoxylanase or a GH67 α-glucuronidase. The combination of these enzymes and the coregulation of their synthesis in all phytopathogenic xanthomonads suggest a unique role that contributes to their potential to cause plant disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by grant USDA-CSREES-SRGP-002216 and in part by Biomass Research & Development Initiative competitive grant 2011-10006-30358 from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

REFERENCES

- 1.Preston JF, Hurlbert JC, Rice JD, Ragunathan A, St John FJ. 2003. Microbial strategies for the depolymerization of glucuronoxylan: leads to the biotechnological applications of endoxylanases. ACS Symp Ser 855:191–210. doi: 10.1021/bk-2003-0855.ch012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuhad RC, Singh A, Eriksson KE. 1997. Microorganisms and enzymes involved in the degradation of plant fiber cell walls. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol 57:45–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.St John FJ, Rice JD, Preston JF. 2006. Paenibacillus sp. strain JDR-2 and XynA1: a novel system for methylglucuronoxylan utilization. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:1496–1506. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.2.1496-1506.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chow V, Nong G, Preston JF. 2007. Structure, function, and regulation of the aldouronate utilization gene cluster from Paenibacillus sp. strain JDR-2. J Bacteriol 189:8863–8870. doi: 10.1128/JB.01141-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shulami S, Gat O, Sonenshein AL, Shoham Y. 1999. The glucuronic acid utilization gene cluster from Bacillus stearothermophilus T-6. J Bacteriol 181:3695–3704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sawhney N, Preston JF. 2014. GH51 arabinofuranosidase and its role in the methylglucuronoarabinoxylan utilization system in Paenibacillus sp. JDR-2. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:6114–6125. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01684-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Potnis N, Krasileva K, Chow V, Almeida NF, Patil PB, Ryan RP, Sharlach M, Behlau F, Dow JM, Momol M, White FF, Preston JF, Vinatzer BA, Koebnik R, Setubal JC, Norman DJ, Staskawicz BJ, Jones JB. 2011. Comparative genomics reveals diversity among xanthomonads infecting tomato and pepper. BMC Genomics 12:146. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Déjean G, Blanvillain-Baufumé S, Boulanger A, Darrasse A, Dugé de Bernonville T, Girard AL, Carrére S, Jamet S, Zischek C, Lautier M, Solé M, Büttner D, Jacques M-A, Lauber E, Arlat M. 2013. The xylan utilization system of the plant pathogen Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris controls epiphytic life and reveals common features with oligotrophic bacteria and animal gut symbionts. New Phytol 198:899–915. doi: 10.1111/nph.12187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun Q, Hu J, Huang G, Ge C, Fang R, He C. 2005. Type-II secretion pathway structural gene xpsE, xylanase- and cellulase secretion and virulence in Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae. Plant Pathol 54:15–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3059.2004.01101.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gottig N, Garavaglia BS, Garofalo CG, Orellano EG, Ottado J. 2009. A filamentous hemagglutinin-like protein of Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri, the phytopathogen responsible for citrus canker, is involved in bacterial virulence. PLoS One 4:e4358. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leite RP Jr, Egel DS, Stall RE. 1994. Genetic analysis of hrp-related DNA sequences of Xanthomonas campestris strains causing diseases of citrus. Appl Environ Microbiol 60:1078–1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huguet E, Hahn K, Wengelnik K, Bonas U. 1998. hpaA mutants of Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria are affected in pathogenicity but retain the ability to induce host-specific hypersensitive reaction. Mol Microbiol 29:1379–1390. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nelson N. 1944. A photometric adaptation of the Somogyi method for the determination of glucose. J Biol Chem 153:375–380. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ge Y, Antoulinakis EG, Gee KR, Johnson L. 2007. An ultrasensitive, continuous assay for xylanase using the fluorogenic substrate 6,8-difluoro-4-methylumbelliferyl beta-d-xylobloside. Anal Biochem 362:63–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2006.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nong G, Rice J, Chow V, Preston JF. 2009. Aldouronate utilization in Paenibacillus sp. strain JDR-2: physiological and enzymatic evidence for coupling of extracellular depolymerization and intracellular metabolism. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:4410–4418. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02354-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bessey OA, Lowry OH, Brock MJ. 1946. A method for the rapid determination of alkaline phosphatase with five cubic millimeters of serum. J Biol Chem 164:321–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu N, Hung M, Chiou S, Tang F, Chiang D, Huang H, Wu C. 1992. Cloning and characterization of a gene required for the secretion of extracellular enzymes across the outer-membrane by Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris. J Bacteriol 174:2679–2687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rozen S, Skaletsky H. 2000. Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. Methods Mol Biol 132:365–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bio-Rad Laboratories. 2006. Real-time PCR applications guide. Bulletin 5279, p 2–6, 34–37. Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hurlbert J, Preston J. 2001. Functional characterization of a novel xylanase from a corn strain of Erwinia chrysanthemi. J Bacteriol 183:2093–2100. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.6.2093-2100.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacAlister TJ, Costerton JW, Thompson L, Thompson J, Ingram JM. 1972. Distribution of alkaline phosphatase within the periplasmic space of gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol 111:827–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nagy T, Emami K, Fontes CM, Ferreira LM, Humphry DR, Gilbert HJ. 2002. The membrane-bound alpha-glucuronidase from Pseudomonas cellulosa hydrolyzes 4-O-methyl-d-glucuronoxylooligosaccharides but not 4-O-methyl-d-glucuronoxylan. J Bacteriol 184:4925–4929. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.17.4925-4929.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Y, Kim SG, Wu J, Huh HH, Lee SJ, Rakwal R, Kumar Agrawal G, Park ZY, Young Kang K, Kim ST. 2013. Secretome analysis of the rice bacterium Xanthomonas oryzae (Xoo) using in vitro and in planta systems. Proteomics 13:1901–1912. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201200454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Szczesny R, Jordan M, Schramm C, Schulz S, Cogez V, Bonas U, Büttner D. 2010. Functional characterization of the Xcs and Xps type II secretion systems from the plant pathogenic bacterium Xanthomonas campestris pv vesicatoria. New Phytol 187:983–1002. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.St John FJ, Rice JJ, Preston JF. 2006. Characterization of XynC from Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis strain 168 and analysis of its role in depolymerization of glucuronoxylan. J Bacteriol 188:8617–8626. doi: 10.1128/JB.01283-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rhee MS, Wei L, Sawhney N, Rice JD, St John FJ, Hurlbert JC, Preston JF. 2014. Engineering the xylan utilization system in Bacillus subtilis for production of acidic xylooligosaccharides. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:917–927. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03246-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Santos CR, Hoffmam ZB, de Matos Martins VP, Zanphorlin LM, de Paula Assis LH, Honorato RV, de Oliveira PSL, Ruller R, Murakami MT. 2014. Molecular mechanisms associated with xylan degradation in Xanthomonas plant pathogens. J Biol Chem 289:32186–32200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.605105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu Q, Chen LL, Ruan X, Chen D, Zhu A, Chen C, Bertrand D, Jiao WB, Hao BH, Lyon MP, Chen J, Gao S, Xing F, Lan H, Chang JW, Ge X, Lei Y, Hu Q, Miao Y, Wang L, Xiao S, Biswas MK, Zeng W, Guo F, Cao H, Yang X, Xu XW, Cheng YJ, Xu J, Liu JH, Luo OJ, Tang Z, Guo WW, Kuang H, Zhang HY, Roose ML, Nagarajan N, Deng XX, Ruan Y. 2013. The draft genome of sweet orange (Citrus sinensis). Nat Genet 45:59–66. doi: 10.1038/ng.2472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stall RE, Marco GM, de Echenique C. 1982. Importance of mesophyll in mature-leaf resistance in cancrosis of citrus. Phytopathology 72:1097–1100. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-72-1097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brunings AM, Gabriel DW. 2003. Xanthomonas citri: breaking the surface. Mol Plant Pathol 4:141–157. doi: 10.1046/j.1364-3703.2003.00163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gottwald TR, Graham JH, Schubert TS. 12 August 2002. Citrus canker: the pathogen and its impact. Plant Health Prog doi: 10.1094/PHP-2002-0812-01-RV. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fry S. 2004. Primary cell wall metabolism: tracking the careers of wall polymers in living plant cells. New Phytol 161:641–675. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.00980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Biely P, Vrsanska M, Tenkanen M, Kluepfel D. 1997. Endo-beta-1,4-xylanase families: differences in catalytic properties. J Biotechnol 57:151–166. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1656(97)00096-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]