Abstract

Background and aim

People with epilepsy are at increased risk of sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) due to ECG-confirmed ventricular tachycardia/fibrillation, as seen in a community-based study. We aimed to determine whether ECG-risk markers of SCA are more prevalent in people with epilepsy.

Methods

In a cross-sectional, retrospective study, we analysed the ECG recordings of 185 people with refractory epilepsy and 178 controls without epilepsy. Data on epilepsy characteristics, cardiac comorbidity, and drug use were collected, and general ECG variables (heart rate (HR), PQ and QRS intervals) assessed. We analysed ECGs for three markers of SCA risk: severe QTc prolongation (male >450 ms, female >470 ms), Brugada ECG pattern, and early repolarisation pattern (ERP). Multivariate regression models were used to analyse differences between groups, and to identify associated clinical and epilepsy-related characteristics.

Results

People with epilepsy had higher HR (71 vs 62 bpm, p<0.001) and a longer PQ interval (162.8 vs 152.6 ms, p=0.001). Severe QTc prolongation and ERP were more prevalent in people with epilepsy (QTc prolongation: 5% vs 0%; p=0.002; ERP: 34% vs 13%, p<0.001), while the Brugada ECG pattern was equally frequent in both groups (2% vs 1%, p>0.999). After adjustment for covariates, epilepsy remained associated with ERP (ORadj 2.4, 95% CI 1.1 to 5.5) and severe QTc prolongation (ORadj 9.9, 95% CI 1.1 to 1317.7).

Conclusions

ERP and severe QTc prolongation appear to be more prevalent in people with refractory epilepsy. Future studies must determine whether this contributes to increased SCA risk in people with epilepsy.

Keywords: Anticonvulsants, Channels, Epilepsy, Sudden Death

Introduction

A recent community-based study found that people with epilepsy had a twofold to threefold increased risk of ECG-confirmed sudden cardiac arrest (SCA), that is, ventricular tachycardia/fibrillation, irrespective of the traditional cardiac risk factors for SCA.1 A 12-lead standard ECG is a potential low-cost screening test for SCA risk. Several ECG markers for SCA risk have been established in the general population; these include severe QTc prolongation,2–4 Brugada ECG pattern (Brugada ECG),5 and early repolarisation pattern (ERP).6–9

QTc prolongation reflects abnormal cardiac repolarisation. In most studies comparing people with epilepsy and without epilepsy, mild QTc prolongation was reported in those with epilepsy,10–12 while others reported similar QTc durations in both groups,13 14 or QTc shortening.15 16 The number of people with severe QTc prolongation was not reported in these studies.

Brugada ECG is characteristic of Brugada syndrome, an inherited disease associated with disrupted cardiac depolarisation.17 Sudden death in young people with structurally normal hearts in epilepsy and Brugada syndrome occurs mainly during rest or sleep.17–19 ERP, long considered a benign and more common variant of the Brugada ECG, was found to be more prevalent in people with idiopathic ventricular fibrillation than in healthy controls.20 21 Subsequently, ERP was identified as an independent predictor of SCA in several population-based studies.6–9

We hypothesise that the prevalence of severe QTc prolongation, Brugada ECG, and ERP, are increased in people with epilepsy; this may (partly) explain the higher SCA risk in epilepsy.

Methods

Cases

Cases consisted of 188 consecutive people with confirmed drug-refractory epilepsy,22 who were assessed at one epilepsy tertiary referral centre between September 2009 and April 2011. In all, a resting 12-lead ECG was recorded as part of the routine assessment on initial evaluation.23 The anonymised data were obtained as part of an audit into epilepsy-associated comorbidities, which was approved as such by the local ethics committee. As all data was acquired during routine clinical care, no informed consent was required.

Controls

Controls were drawn from a substudy of The Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety.24 They were 18–65 years old, randomly selected from a general practitioners’ database in the Amsterdam area, and had no lifetime history of a psychiatric disorder.24 A resting 12-lead ECG was recorded in 179 subjects. We excluded all those with a diagnosis of active epilepsy or current use of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) (n=1), leaving 178 controls. The study was approved by the local ethics committee. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

ECG analysis

In all participants, conventional characteristics of the 12-lead ECG (heart rate (HR), PQ, and QRS duration) were automatically determined. Brugada ECG was classified as type-1 (coved ST-segment elevation in right precordial ECG leads ≥0.2 mV followed by a negative T-wave with little or no isoelectric separation), type 2 (coved ST-segment elevation in V1–V3 followed by a gradually descending ST-segment elevation remaining ≥0.1 mV above the baseline and a positive or biphasic T-wave that results in a saddleback configuration), or type 3 (right precordial ST-segment elevation of ≥0.1 mV of saddleback type, coved type, or both), according to Brugada syndrome consensus criteria.25 QTc duration was calculated using Bazett's formula to correct for HR: QT/√RR.26 Severe QTc prolongation was defined according to the European Society of Cardiology Guidelines: >450 ms in men, >470 ms in women.27 ERP was defined as J-point elevation ≥0.1 mV in ≥2 adjacent leads with either slurring or notching morphology.7 20 Leads V1–V3 were not assessed to avoid confusion with ECG patterns typical of Brugada syndrome. ECGs with intraventricular conduction delay (QRS duration of ≥0.12 s), which precluded reliable assessment of QTc duration, Brugada ECG or ERP (n=3, all cases), were excluded from analysis.7 20

An experienced cardiologist (HLT) reviewed all ECGs for Brugada ECG pattern to ensure consistent classification. The QTc interval including the presence/absence of severe QTc prolongation and ERP were assessed by two blinded researchers (RJL and MB). In case of disagreement between the examiners, HLT provided the final verdict. There was no systematic difference between the reviewers in their analysis of the QTc interval (paired t test: 0.59) or ERP (κ score 0.75).

Assessment of comorbidities and medication use

Variables were collected from medical records (in cases) and on self-reported/assessed information during a face-to-face interview (in controls). These variables were: gender, age, presence of ≥2 cardiac risk factors (hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, diabetes mellitus), presence of heart disease, and medication use. We defined four drug categories: (1) QT-prolonging medication (http://www.azcert.org), (2) depolarisation-blocking drugs (http://www.brugadadrugs.org), (3) cardiovascular drugs (β-adrenoreceptor blockers, calcium channel antagonists, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, diuretics, angiotensin-II receptor blockers, nitrates, platelet aggregation inhibitors and/or statins) and (4) lipid-lowering drugs. Some drugs fit in more than one category.

Among AEDs, QT-prolonging drugs were phenytoin and felbamate, while depolarisation-blocking drugs included carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, phenytoin and lamotrigine.

In people with epilepsy, additional data were recorded including epilepsy aetiology (symptomatic/non-symptomatic), history of epilepsy surgery (yes/no), age of onset and duration of epilepsy, seizure frequency (≥1 vs <1/month), polytherapy (≥2 AEDs), presence of a learning disability, and family history of epilepsy (≥2 family members with epilepsy).

Statistical analysis

Differences between cohorts in baseline characteristics and ECG parameters were analysed using χ2 statistics for categorical variables (Pearson/Fisher's Exact test where appropriate) and Student t test/Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables. We performed multivariate logistic regression models to determine whether epilepsy was independently associated with Brugada ECG, severe QTc prolongation, or ERP. We employed two models: the first included all determinants that were univariately associated (p<0.1) with outcome, whereas the second model included only those determinants that also changed the point estimate by ≥5%. As severe QTc prolongation was not seen in controls, we used penalised logistic regression analysis to perform multivariate analysis applying the same strategy as above. Among people with epilepsy the same approach was used to determine which clinical (comorbidities and medication use) and epilepsy characteristics were associated with these SCA predictors. Statistics were performed in R (penalised logistic regression analysis; R statistical package, V.2.14, package logistf, V.1.10), and in SPSS (all other analyses; V.17.0 for Windows, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

Baseline characteristics

ECGs of 185 people with epilepsy and 178 controls were analysed (table 1). People with epilepsy were more often male (non-significant), were significantly younger, and more frequently used drugs with QT-prolonging or depolarisation-blocking effects. QT-prolonging drugs used were AEDs (46%), antidepressants (30%), antipsychotics (20%), or antiemetics (5%), whereas depolarisation-blocking drugs were almost exclusively AEDs (99%). The prevalence of ≥2 cardiac risk factors, heart disease, cardiovascular medication and lipid lowering drugs did not differ between groups.

Table 1.

Distribution of clinical characteristics in cases and controls

| Epilepsy cohort (n=185) | Control cohort (n=178) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Male gender (%) | 85 (46) | 65 (37) | 0.068 |

| Mean age, years | 38 (13.3) | 48 (12.5) | <0.001 |

| Cardiac comorbidity (%) | |||

| ≥2 cardiac risk factors | 7 (4) | 11 (6) | 0.293 |

| Myocardial infarction | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 0.969 |

| All-heart disease | 3 (2) | 3 (2) | 0.962 |

| Medication use (%) | |||

| QT-prolonging drugs | 39 (21) | 1 (1) | <0.001 |

| Depolarisation-blocking drugs | 145 (78) | 1 (1) | <0.001 |

| Cardiovascular drugs | 32 (17) | 26 (15) | 0.484 |

| Lipid-lowering drugs | 9 (5) | 6 (3) | 0.475 |

| ECG parameters | |||

| Heart rate, beats per min | 70.7 (11.4) | 61.8 (9.8) | <0.001 |

| PQ, msec | 162.8 (26.0) | 152.6 (32.6) | 0.001 |

| QRS, msec | 88.7 (13.8) | 91.0 (10.3) | 0.066 |

| QTc, msec | 404.8 (33.0) | 393.5 (24.8) | <0.001 |

| Brugada ECG pattern (%) | 3 (2) | 2 (1) | >0.999 |

| Severe QTc prolongation (%) | 10 (5) | 0 (0) | 0.002 |

| ERP (lateral and/or inferior) (%) | 62 (34) | 23 (13) | <0.001 |

| ERP (inferior) (%) | 50 (27) | 20 (11) | <0.001 |

Dichotomous data are expressed as n (%), and continuous data as mean (SD) unless indicated otherwise. p Values are calculated with the χ2 or the Fisher's exact test in dichotomous data, and with the Student t test in continuous data unless indicated otherwise. Cardiac risk factors include hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, and diabetes.

ERP, early repolarisation pattern.

ECG analysis

People with epilepsy had a higher HR (71 vs 62 bpm, p<0.001), a longer PQ interval, (163 vs 153 ms, p=0.001), and shorter (though not statistically significant) QRS interval (89 vs 91 ms, p=0.07). Mean QTc duration was also longer: 405 vs 394 ms, p<0.001. Brugada ECG was equally prevalent in both groups (2% vs 1%, p>0.999). The prevalence of severe QTc prolongation (5% vs 0%, p=0.002) and ERP (34% vs 13%, p<0.001; figure 1) was higher in cases than in controls: table 1.

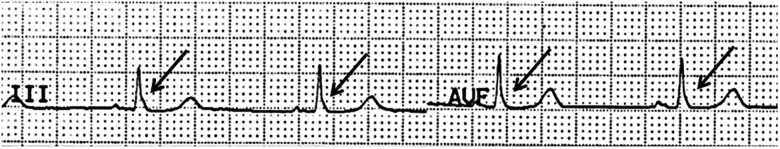

Figure 1.

Person with epilepsy and early repolarisation pattern in the inferior leads. J-point elevation of ≥0.1 mV with slurring morphology in two adjacent leads (III and aVF).

Multivariate analysis of severe QTc prolongation and ERP

Apart from epilepsy, severe QTc prolongation was univariately associated with (female) gender, (lower) age, (higher) HR, and use of depolarisation-blocking drugs (see online supplementary table e-1). QT-prolonging drugs were not used by those with severe QTc prolongation. Due to the absence of severe QTc prolongation in the control cohort, it was not possible to separate the effects of epilepsy and use of depolarisation-blocking drugs (99% of which were AEDs) in multivariate analysis. Therefore, only epilepsy, gender, age, and HR were entered in the model (penalised logistic regression, table 2). After correction for these variables epilepsy remained associated with severe QTc prolongation (table 2, Model A: ORadj 9.9 (1.1 to 1317.7).

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of determinants of early repolarisation pattern in cases (n=185) and controls (n=178)

| Epilepsy cohort (n=185) | Control cohort (n=178) | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) (A) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) (B) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brugada ECG | 3 (2%) | 2 (1%) | 1.5 (0.2 to 8.8) | NA | NA |

| Severe QTc-prolongation | 10 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 21.0 (2.7 to 2708.2) | 9.9 (1.1 to 1317.7) | 9.9 (1.1 to 1317.7) |

| ERP | 62 (34%) | 23 (13%) | 3.4 (2.0 to 5.8) | 2.3 (1.0 to 5.5) | 2.4 (1.1 to 5.5) |

Dichotomous data are expressed as n (%) unless indicated otherwise. ORs are calculated using penalised logistic regression analysis (R statistical package) for severe QTc prolongation and logistic regression analysis for ERP. Covariates were entered in the analysis if they were associated (p<0.10) with pathological with severe QTc prolongation (see online supplementary table e-1) or ERP (see online supplementary table e-2).

A: all determinants that were univariately associated with severe QTc prolongation (gender, age, heart rate) or ERP (gender, heart disease, QT-prolonging drugs, depolarisation-blocking drugs, cardiovascular drugs, heart rate) were entered.

B: all determinants that changed the β by ≥5% and were univariately associated with severe QTc prolongation (gender, heart rate) or ERP (depolarisation-blocking drugs, heart rate) and changed the β by ≥5% were entered.

ERP, early repolarisation pattern.

ERP was univariately associated with epilepsy, (male) gender, heart disease, (higher) HR, and the use of QT-prolonging, depolarisation-blocking, and cardiovascular drugs (see online supplementary table e-2). Multivariate analysis showed epilepsy to be independently associated with ERP: table 2, Model B: ORadj 2.4 (95% CI 1.1 to 5.5).

In those with epilepsy (n=185) none of the epilepsy characteristics were associated with either severe QTc prolongation or ERP (see online supplementary tables e-3 and e-4).

Discussion

We systematically analysed the prevalence of three ECG-risk markers of SCA and found that severe QTc prolongation and ERP were more frequent in people with refractory epilepsy.

Our study had some limitations. There were several differences between cases and controls: people with epilepsy were younger and more likely to be male. Younger age may result in a lower QTc interval and a higher ERP prevalence.28 29 In view of the relatively small age differences in our study, however, only minor effects on severe QTc prolongation and ERP should be expected. Accordingly, having epilepsy remained significantly associated with severe QTc prolongation after correction for age. ERP is more frequently found in males, but having epilepsy remained an independent determinant after accounting for gender differences.29 As for severe QTc prolongation, the association with epilepsy also remained significant after correction for this variable in multivariate analysis, and using gender-specific cut-off points. In accordance with previous studies, HR was higher in cases than in controls: this may be due to epilepsy-related abnormalities of cardiac autonomic balance.30 HR is incorporated in the definition of severe QTc prolongation, but the use of Bazett's formula may lead to an overestimation of QTc duration in people with higher HR: particularly those with epilepsy.26 We, therefore, included HR in the multivariate analysis of severe QTc prolongation and ERP. As severe QTc prolongation as SCA marker has been defined using Bazett's formula and for study comparability, we did not use alternative QT correction formulae.

We found that QTc duration was increased in people with epilepsy when compared with controls. This is concordant with some,10–12 but not all previous studies.13–16 Conflicting findings may be explained by differences in epilepsy severity or medication use between study populations. We analysed people with refractory, more severe epilepsy than in previous studies. QTc duration was dichotomised in one study (>440 ms, yes vs no), allowing comparison between ours and their results.11 By contrast with our findings, they reported a similar prevalence of QTc intervals >440 ms in cases and controls.11 Our more stringent, gender-corrected definition of severe QTc prolongation (>450 ms in men, >470 ms in women), is recommended, however, by the current guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology and has been used in the more recent large-scale prospective, population-based studies of SCA risk.3 27 We, therefore, believe our criteria to be more clinically relevant.

In our analysis of severe QTc prolongation, we could not separate the effects of epilepsy and use of depolarisation-blocking drugs. Severe QTc prolongation was only present in people with epilepsy and depolarisation-blocking drugs (predominantly AEDs) were used almost exclusively by this group. We believe the use of depolarisation-blocking drugs is more likely a proxy for epilepsy severity than directly affecting cardiac repolarisation. In this study, use of depolarisation-blocking drugs was not related with severe QTc prolongation when analysing only the cohort with epilepsy. Use of depolarisation-blocking AEDs was not associated with QTc prolongation in cross-sectional studies,11–14 nor in a prospective drug trial.31 QT-prolonging drugs are more likely to contribute to severe QTc prolongation, but none of the individuals with this ECG risk marker used these drugs.

In the multivariate analysis of ERP, we could separate the effects of epilepsy and depolarisation-blocking drugs, and found that the latter variable was not an independent determinant. Due to the higher prevalence of this SCA risk marker in our population, the evidence for the association of epilepsy with ERP is stronger than with severe QTc prolongation.

Our findings might explain why people with epilepsy carry an increased risk of SCA.1 ERP was associated with a 1.7-fold increased risk of SCA in a recent meta-analysis,32 and seizures may facilitate the transition from ERP into Brugada ECG.33 Severe QTc prolongation is associated with a threefold increased risk of SCA, which may be aggravated by additional peri-ictal QTc prolongation.34 35

Severe QTc prolongation, ERP, and certain epilepsy syndromes are associated with sodium and potassium channel mutations.36 37 Conceivably, a single mutation expressed in heart and brain might confer a propensity for epilepsy and an innate vulnerability to cardiac arrhythmias, thereby linking epilepsy with these ECG-markers and SCA.

Routine performance of a 12-lead ECG in all adults with suspected epilepsy is recommended by the NICE guidelines but not listed in the AES/AAN guidelines.23 38 The diagnostic yield of this practice has not yet been determined. Our study suggests that an increased prevalence of severe QTc prolongation and ERP occurs in people with epilepsy. Routine ECG evaluation in people with epilepsy may be of importance in guiding clinicians in their choice of AED therapy, for example, avoidance of QT-prolonging or depolarisation-blocking drugs in people with ECG markers of increased SCA risk.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr S. Balestrini for her assistance with data collection, to Dr M. Tanck for his statistical assistance, and to Dr GS Bell for reviewing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: Study designed by RJL, JWS, HLT and RDT. Data was collected by RJL, MTB, JN, MB, AS and BP. Data analysed by RJL, MTB, JWS, HLT and RDT. Manuscript drafted by RJL and MTB and critically reviewed by JWS, HLT and RDT. All approved the final draft.

Funding: This study was supported by the Dutch Epilepsy Foundation (project number 10-07), Christelijke Vereniging voor de Verpleging van Lijders aan Epilepsie (Nederland), and Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO, grant ZonMW Vici 918.86.616).

Competing interests: JWS receives research support from Epilepsy Society, the Dr Marvin Weil Epilepsy Research Fund, Eisai, GSK, UCB Pharma, the WHO, and the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and has been consulted by and received fees for lectures from GSK, Eisai and UCB Pharma. RDT receives research support from NUTS Ohra Fund, Medtronic, and AC Thomson Foundation, and has received fees for lectures from Medtronic, UCB Pharma and GSK. JWS and RDT are members of PRISM—the Prevention and Risk Identification of SUDEP Mortality Consortium, which is funded by the NIH (NBIH/NINDS-1P20NS076965-01). JN was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation-Fellowships for prospective researchers and the SICPA Foundation, Prilly, Switzerland.

Ethics approval: Local ethics committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Bardai A, Lamberts RJ, Blom MT, et al. Epilepsy is a risk factor for sudden cardiac arrest in the general population. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e42749 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3419243/pdf/pone.0042749.pdf (accessed 17 Jan 2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Algra A, Tijssen JG, Roelandt JR, et al. QTc prolongation measured by standard 12-lead electrocardiography is an independent risk factor for sudden death due to cardiac arrest. Circulation 1991;83:1888–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Straus SM, Kors JA, de Bruin ML, et al. Prolonged QTc interval and risk of sudden cardiac death in a population of older adults. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:362–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soliman EZ, Prineas RJ, Case LD, et al. Electrocardiographic and clinical predictors separating atherosclerotic sudden cardiac death from incident coronary heart disease. Heart 2011;97:1597–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matsuo K, Akahoshi M, Nakashima E, et al. The prevalence, incidence and prognostic value of the Brugada-type electrocardiogram: a population-based study of four decades. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;38:765–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tikkanen JT, Anttonen O, Junttila MJ, et al. Long-term outcome associated with early repolarization on electrocardiography. N Engl J Med 2009;361: 2529–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sinner MF, Reinhard W, Mueller M, et al. Association of early repolarization pattern on ECG with risk of cardiac and all-cause mortality: a population-based prospective cohort study (MONICA/KORA). PLoS Med 2010;7:e1000314 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2910598/pdf/pmed.1000314.pdf (accessed 17 Jan 2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haruta D, Matsuo K, Tsuneto A, et al. Incidence and prognostic value of early repolarization pattern in the 12-lead electrocardiogram. Circulation 2011;123:2931–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rollin A, Maury P, Bongard V, et al. Prevalence, prognosis, and identification of the malignant form of early repolarization pattern in a population-based study. Am J Cardiol 2012;110:1302–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drake ME, Reider CR, Kay A. Electrocardiography in epilepsy patients without cardiac symptoms. Seizure 1993;2:63–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neufeld G, Lazar JM, Chari G, et al. Cardiac repolarization indices in epilepsy patients. Cardiology 2009;114:255–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dogan EA, Dogan U, Yıldız GU, et al. Evaluation of cardiac repolarization indices in well-controlled partial epilepsy: 12-Lead ECG findings. Epilepsy Res 2010;90:157–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akalin F, Tirtir A, Yilmaz Y. Increased QT dispersion in epileptic children. Acta Paediatr 2003;92:916–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krishnan V, Krishnamurthy KB. Interictal 12-lead electrocardiography in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2013;29:240–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Teh HS, Tan HJ, Loo CY, et al. Short QTc in epilepsy patients without cardiac symptoms. Med J Malaysia 2007;62:104–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramadan M, El-Shahat N, Omar AA, et al. Interictal electrocardiographic and echocardiographic changes in patients with generalized tonic-clonic seizures. Int Heart J 2013;54:171–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Postema PG, van Dessel PF, Kors JA, et al. Local depolarization abnormalities are the dominant pathophysiologic mechanism for type 1 electrocardiogram in brugada syndrome: a study of electrocardiograms, vectorcardiograms, and body surface potential maps during ajmaline provocation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:789–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Surges R, Thijs RD, Tan HL, et al. Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy: risk factors and potential pathomechanisms. Nat Rev Neurol 2009;5:492–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lamberts RJ, Thijs RD, Laffan A, et al. Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy: people with nocturnal seizures may be at highest risk. Epilepsia 2012;53:253–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haïssaguerre M, Derval N, Sacher F, et al. Sudden cardiac arrest associated with early repolarization. New Engl J Med 2008;358:2016–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosso R, Kogan E, Belhassen B, et al. J-point elevation in survivors of primary ventricular fibrillation and matched control subjects: incidence and clinical significance. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52:1231–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwan P, Arzimanoglou A, Berg AT, et al. Definition of drug resistant epilepsy: consensus proposal by the ad hoc Task Force of the ILAE Commission on Therapeutic Strategies. Epilepsia 2010;51:1069–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.NICE clinical guideline 137. The epilepsies: the diagnosis and management of the epilepsies in adults and children in primary and secondary care. http://publications.nice.org.uk (accessed 17 Jan 2014).

- 24.Penninx BW, Beekman AT, Smit JH, et al. The Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA): rationale, objectives and methods. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2008;17:121–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilde AA, Antzelevitch C, Borggrefe M, et al. Proposed diagnostic criteria for the Brugada syndrome: consensus report. Circulation 2002;106:2514–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luo S, Michler K, Johnston P, et al. A comparison of commonly used QT correction formulae: the effect of heart rate on the QTc of normal ECGs. J Electrocardiol 2004;37(Suppl):81–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Committee for Proprietary Medicinal Products. Points to consider: the Assessment of the Potential for QT Interval Prolongation by Non-Cardiovascular Medicinal Products. London, The European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mangoni AA, Kinirons MT, Swift CG, et al. Impact of age on QT interval and QT dispersion in healthy subjects: a regression analysis. Age Ageing 2003;32:326–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walsh JA, Ilkhanoff L, Soliman EZ, et al. Natural history of the early repolarization pattern in a biracial cohort: CARDIA (Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults) Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61:863–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sevcencu C, Struijk JJ. Autonomic alterations and cardiac changes in epilepsy. Epilepsia 2010;51:725–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saetre E, Abdelnoor M, Amlie JP, et al. Cardiac function and antiepileptic drug treatment in the elderly: a comparison between lamotrigine and sustained-release carbamazepine. Epilepsia 2009;50:1841–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu SH, Lin XX, Cheng YJ, et al. Early repolarization pattern and risk for arrhythmia death: a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;61:645–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gussak I, Antzelevitch C. Early repolarization syndrome: clinical characteristics and possible cellular and ionic mechanisms. J Electrocardiol 2000;33:299–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Surges R, Scott CA, Walker MC. Enhanced QT shortening and persistent tachycardia after generalized seizures. Neurology 2010;74:421–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seyal M, Pascual F, Lee CY, et al. Seizure-related cardiac repolarization abnormalities are associated with ictal hypoxemia. Epilepsia 2011;52:2105–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnson JN, Hofman N, Haglund CM, et al. Identification of a possible pathogenic link between congenital long QT syndrome and epilepsy. Neurology 2009;72:224–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Watanabe H, Nogami A, Ohkubo K, et al. Electrocardiographic characteristics and SCN5A mutations in idiopathic ventricular fibrillation associated with early repolarization. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2011;4:874–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krumholz A, Wiebe S, Gronseth G, et al. Practice Parameter: evaluating an apparent unprovoked first seizure in adults (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Epilepsy Society. Neurology 2007;69:1996–2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.