Abstract

Objective:

To characterize B-cell subsets in patients with muscle-specific tyrosine kinase (MuSK) myasthenia gravis (MG).

Methods:

In accordance with Human Immunology Project Consortium guidelines, we performed polychromatic flow cytometry and ELISA assays in peripheral blood samples from 18 patients with MuSK MG and 9 healthy controls. To complement a B-cell phenotype assay that evaluated maturational subsets, we measured B10 cell percentages, plasma B cell–activating factor (BAFF) levels, and MuSK antibody titers. Immunologic variables were compared with healthy controls and clinical outcome measures.

Results:

As expected, patients treated with rituximab had high percentages of transitional B cells and plasmablasts and thus were excluded from subsequent analysis. The remaining patients with MuSK MG and controls had similar percentages of total B cells and naïve, memory, isotype-switched, plasmablast, and transitional B-cell subsets. However, patients with MuSK MG had higher BAFF levels and lower percentages of B10 cells. In addition, we observed an increase in MuSK antibody levels with more severe disease.

Conclusions:

We found prominent B-cell pathology in the distinct form of MG with MuSK autoantibodies. Increased BAFF levels have been described in other autoimmune diseases, including acetylcholine receptor antibody–positive MG. This finding suggests a role for BAFF in the survival of B cells in MuSK MG, which has important therapeutic implications. B10 cells, a recently described rare regulatory B-cell subset that potently blocks Th1 and Th17 responses, were reduced, which suggests a potential mechanism for the breakdown in immune tolerance in patients with MuSK MG.

Autoantibodies to muscle-specific tyrosine kinase (MuSK)1 are found in 38%–47% of patients with myasthenia gravis (MG) who do not have detectable antibodies to the acetylcholine receptor (AChR).2,3 Patients with MuSK MG may present with a phenotype distinct from AChR MG, with predominant bulbar, neck, and proximal muscle weakness, frequently with marked atrophy of the involved muscles.4 Patients with MuSK MG typically respond poorly to acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, have fewer thymic histopathologic changes, and rapidly improve with therapeutic plasma exchange (TPE).5–7 Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) studies in Dutch and Italian populations showed a strong association between MuSK MG and HLA-DQ5.8,9 Immunologic studies in this disease have established a pathogenic role for the autoantibodies, which are mainly IgG4,10,11 and other reports have described reduced autoantibody titers with corresponding clinical improvement after anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy.12 These differences in the clinical features, thymic pathology, HLA associations, and response to immunomodulatory therapy between MuSK and AChR MG suggest that the 2 forms of MG have distinct immunopathogenic features that could lead to different responses to current and developing treatments.

Although much is known about the cellular immunology of AChR-antibody MG, MuSK MG is poorly understood. We recently reported T-cell functionality in MuSK MG and demonstrated increased polyfunctional T cells and prominent inflammatory responses consistent with Th1 and Th17 activity.13 Whereas regulatory T cell (Treg) pathology is well-documented in AChR-antibody MG,14,15 we could not associate this increase in T-cell function with changes in the Treg population in MuSK MG, as we found no differences in the percentages of CD25+ FOXP3+ Tregs.

Interleukin (IL)-10–producing B10 cells are strong inhibitors of B- and T-cell responses and are vital in preventing the onset of autoimmune diseases.16–18 B10 cells have only been studied in rituximab-treated patients with MG who were predominantly AChR antibody–positive.19 This regulatory B-cell population is of interest as a potential immunopathologic mechanism in MuSK MG. Accordingly, we undertook a comprehensive analysis of B cells in healthy controls and patients with MuSK MG.

METHODS

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

This study was approved by the Duke University and University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Institutional Review Boards. Informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Study population.

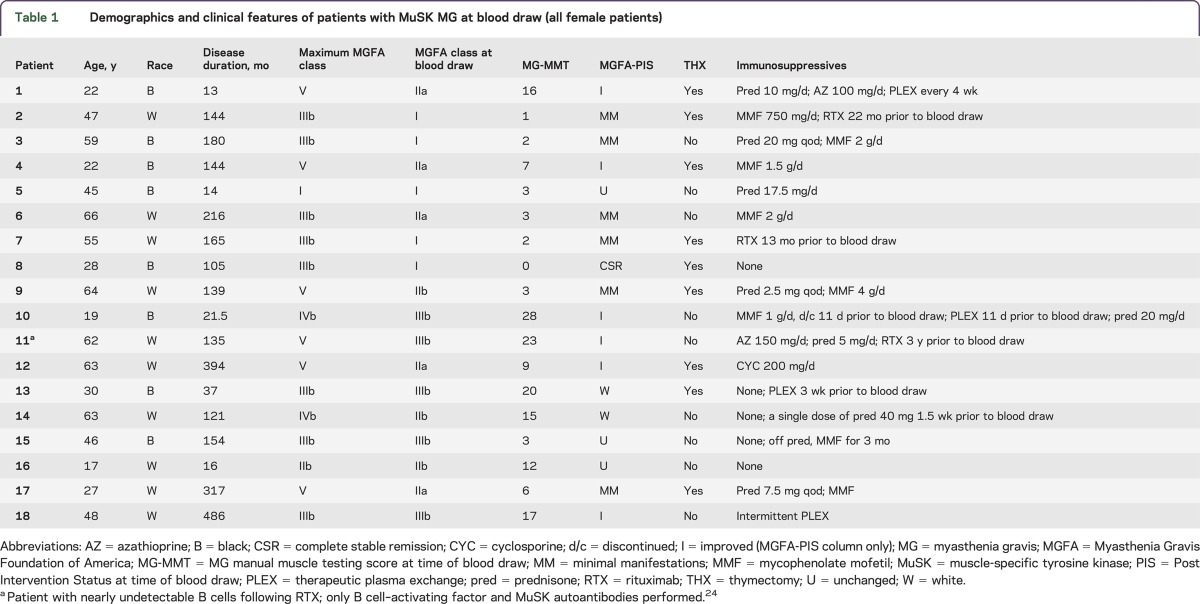

Patients with MuSK MG were recruited from the Duke and University of North Carolina MG Clinics (2010–2014). In this convenience cohort, we obtained blood samples from 18 female patients with MuSK MG (mean age 44 years; range 17–66 years) (table 1). All patients had detectable anti-MuSK antibodies on available testing at the time of diagnosis (Athena Diagnostics, Worcester, MA) as well as clinical and electrodiagnostic features consistent with MuSK MG. Clinical data collected from consenting patients included demographics, duration of disease, immunosuppressive medications, thymectomy status, Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America (MGFA) severity class, MGFA Post Intervention Status, and MG manual muscle testing (MG-MMT) (table 1).20,21 In all cases, the blood draw occurred more than 1 year after onset of symptoms. Nine patients had previously undergone thymectomy, and none of these patients had a thymoma or hyperplasia. The maximum MGFA severity class at any point after disease onset was at least moderate to severe generalized weakness (MGFA severity class III or IV) in all but 2 patients; 6 patients experienced “crisis” requiring mechanical intubation at some point after disease onset. Six patients were not on chronic immunotherapy at the time of the blood draw (1 completely treatment-naive); 1 patient had received a course of TPE 3 weeks prior to the blood sample and another received intermittent TPE. The remaining patients were on monotherapy with prednisone, cyclosporine, or mycophenolate mofetil, or combination therapy with these agents. Three patients had received rituximab infusions in the past.

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical features of patients with MuSK MG at blood draw (all female patients)

Healthy controls.

Blood samples were obtained from 9 healthy controls (6 women) weighing at least 110 pounds and not receiving treatment for another autoimmune disease. Controls were matched to the patients as closely as possible with regard to age and sex.

Isolation and storage of mononuclear peripheral blood cells.

Peripheral blood was collected in acid-citrate-dextrose tubes (BD Vacutainer, Franklin Lake, NJ). Mononuclear cells were separated by Ficoll density gradient centrifugation, washed, and counted prior to storage. Cells were resuspended in a 90% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gemini, West Sacramento, CA) and 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) solution and progressively cooled to −80°C in a CoolCell cell freezing container (BioCision, Larkspur, CA). The following day, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were transferred to liquid nitrogen for long-term storage.13

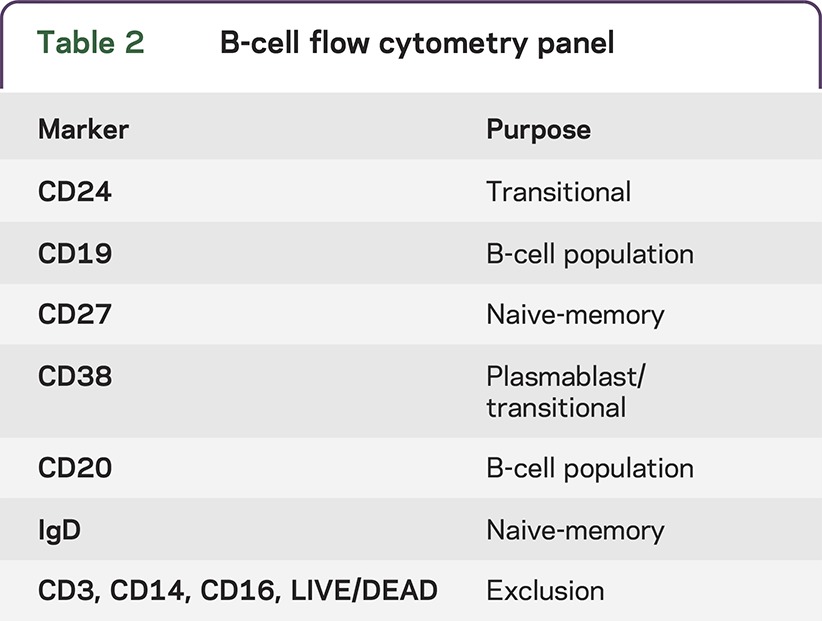

B-cell phenotyping.

A total of 106 PBMCs were plated in 96-well round-bottom plates in RPMI + 10% FBS (Gemini) + 1% penicillin, streptomycin, and l-glutamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). After centrifugation and removal of media, cells were surface stained with 50 μL of a cocktail mix consisting of titrated volumes of LIVE/DEAD violet dye (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY); anti-CD3, anti-CD14, and CD16 Pacific Blue; anti-CD19 PcP-Cy5.5; anti-CD27 APC; anti-IgD PE; anti-CD20 FITC; anti-CD24 PE-Cy7 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA); and anti-CD38 APC-AF700 (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA) (table 2). A “dump” channel consisting of LIVE/DEAD dye and CD3, CD14, and CD16 Pacific Blue was used to exclude dead cells, T cells, and monocytes. After fixing the cells with 1% paraformaldehyde (PFA), they were acquired on a LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA).

Table 2.

B-cell flow cytometry panel

Quantitative detection of BAFF.

Quantitative detection of B cell–activating factor (BAFF) in plasma was performed using the Human BAFF Instant ELISA kit (eBioscience, San Diego, CA). Briefly, undiluted plasma was added to a microwell plate coated with lyophilized polyclonal antibody to human BAFF, biotin conjugate (anti-human BAFF polyclonal antibody), and sample diluent. Following incubation, unbound biotin-conjugated, anti-human BAFF antibodies are removed during a wash step, and a substrate reactive to horseradish peroxidase is added to the wells. The colored reaction is stopped using 1M phosphoric acid, and absorbance was measured at 450 nm using SpectraMax M2 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

B10 cell staining.

Following previously published methods,22 2 × 106 PBMCs resuspended in RPMI + 10% FBS + 1% penicillin, streptomcyin, and l-glutamine were stimulated with 10 μg/mL LPS (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and 1 μg/mL CD40L (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) for 48 hours at 37°C.22 Forty-eight hours allows for the detection of both B10 and B10 progenitor cells, which are cells capable of maturing into IL-10 competent cells after stimulation.22 For the final 5 hours of incubation, PMA (1 μg/mL, Sigma-Aldrich), ionomycin (0.25 μg/mL, Sigma-Aldrich), and brefeldin A (1:1,000 dilution, BD Biosciences) were added to the wells. After this period, cells were collected and stained with 50 μL of a cocktail mix consisting of titrated volumes of LIVE/DEAD violet dye; anti-CD3, anti-CD14, and anti-CD16 Pacific Blue; and anti-CD19 PcP Cy5.5 (BD Biosciences). Following a 30-minute incubation at 4°C, cells were treated with cytofix/cytoperm (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Then, anti-IL-10 Alexa Fluor 647 (eBiosciences) was added and incubated at 4°C for 30 minutes. Lastly, cells were fixed with 1% PFA and acquired on an LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).13

MuSK autoantibody levels.

Plasma samples from patients with MuSK MG (N = 9) were tested for levels of anti-MuSK antibodies using a MuSK antibody immunoprecipitation assay kit (RSR Ltd, Cardiff, UK). Samples with values outside the measurement range were further diluted using normal plasma. The dilutions used were as follows: 1:10, 1:20, 1:40, 1:100, and 1:200. The results are expressed as nmol/L of MuSK protein bound, and positivity is defined as >0.05 nmol/L.

Data analysis and statistics.

Flow cytometry data were analyzed using Flowjo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR). B-cell subsets were summarized as percentages of the total B-cell population and log transformations were performed on immunologic data. Student t tests were used to determine statistical significance between groups, and p < 0.05 was set as the threshold for statistical significance. The p values and Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated with Prism software (Graph Pad, La Jolla, CA).

RESULTS

MuSK antibodies.

We quantitated MuSK autoantibody levels in plasma obtained concurrently with the B-cell analysis in patients previously diagnosed with MuSK MG (range 1.93–181.01 nmol/L). One patient had MuSK autoantibody levels below the 0.05 nmol/L positivity threshold and was excluded from the study. Notably, we observed an increase in MuSK autoantibody levels in patients with severe disease, as measured by MG-MMT scores (r = 0.75; p = 0.02), and there was a trend toward a negative correlation between MuSK autoantibody levels and disease duration that did not meet statistical significance (r = −0.53; p = 0.13) (data not shown). Our results suggest that unlike AChR MG, MuSK autoantibodies can be a novel biomarker for disease severity.

B-cell phenotypes in MuSK MG.

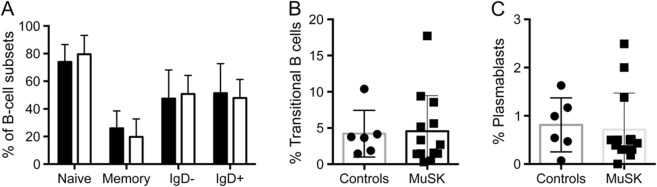

We performed flow cytometry assays in accordance with a standardized Human Immunology Project Consortium panel that discriminates subsets of B cells, including naïve, memory, isotype-switched, transitional, and plasmablasts.23 Three patients previously treated with rituximab (13–36 months prior to blood draw) had a dramatically different B-cell phenotype, with either nearly undetectable B cells or high percentages of transitional B cells and plasmablasts.24 Because of these findings, which are consistent with prior reports of B-cell recovery after rituximab, these patients were excluded from all subsequent analyses.25 We found no differences in the percentages of B-cell subsets or total B cells between healthy controls and patients with MuSK MG not treated with rituximab (figure 1, A–C) and no differences between immunosuppressed and nonimmunosuppressed patients (data not shown). These findings indicate that B-cell subset percentages are not altered in patients with MuSK MG.

Figure 1. Examination of MuSK antibody levels and B-cell subsets.

Flow cytometric analysis (n = 13) using standardized Human Immunology Project Consortium panels to identify (A) naive, memory, IgD−, and IgD+ B cells, along with (B) transitional B cells and (C) plasmablasts. Plasmablasts, IgD−, and IgD+ B cells were gated from CD19+ CD27+ memory B cells. Transitional cells were gated from CD19+ cells. MuSK = muscle-specific tyrosine kinase.

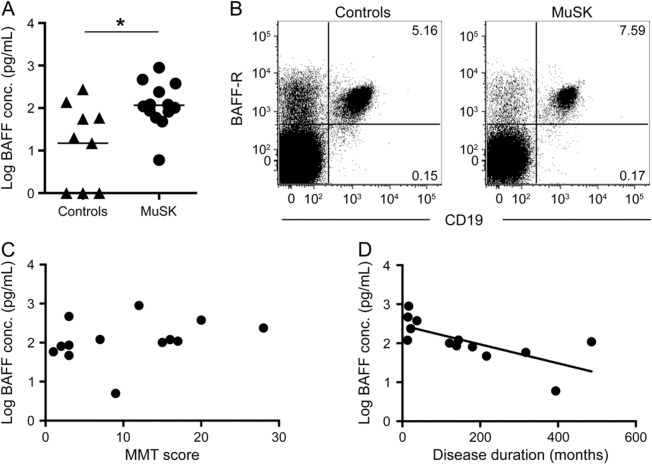

BAFF analysis in MuSK MG.

We also examined whether autoreactive B cells in MuSK MG were associated with increased BAFF levels. BAFF is essential for the survival, maturation, and homeostasis of B cells, and autoreactive B cells seem to be more dependent on BAFF for survival.26,27 Similar to other autoimmune diseases, we found higher concentrations of BAFF in patients with MuSK MG than in controls (figure 2A). However, examination of BAFF receptor expression revealed no differences in the mean percentages of CD19+ cells from healthy controls (96.6%) and patients with MuSK MG (95.6%) (figure 2B). There was no difference in BAFF levels between immunosuppressed and nonimmunosuppressed patients. Further analysis revealed that the highest plasma BAFF levels are found early in disease (r = −0.70; p = 0.008), but no effect was observed with regard to disease severity (figure 2, C and D). These findings suggest that higher BAFF levels could be a critical factor in the generation, maturation, and survival of MuSK MG autoreactive B cells.

Figure 2. Comparison of BAFF levels in controls and patients with MuSK.

(A) ELISA performed on plasma samples shows higher B cell–activating factor (BAFF) levels in patients with muscle-specific tyrosine kinase (MuSK) myasthenia gravis(MG) (p = 0.025). (B) Representative flow cytometry plots depict the surface expression of BAFF receptors (BAFF-R) on CD19+ cells, which was similar in healthy controls and patients with MuSK. Cells are gated on viable lymphocytes. (C, D) Log-transformed data of BAFF concentration (conc.) and MG manual muscle testing (MG-MMT) scores and BAFF concentration and disease duration (p = 0.008).

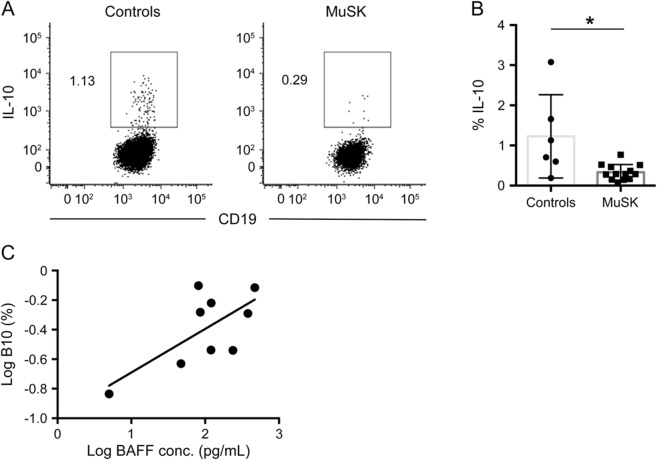

B10 cells in MuSK MG.

B10 cells are a regulatory subset of B cells characterized by their ability to produce IL-10. To determine whether breakdown in immune tolerance in MuSK MG may be attributable to a reduction in B10 cells, we performed a 48-hour in vitro stimulation to identify both B10 and B10 progenitor cells.24 After intracellular cytokine staining, we observed a reduction of B cells capable of producing IL-10 in patients with MuSK MG (0.37% vs 1.23%; p = 0.02) (figure 3, A and B). Further analysis of B10 cells demonstrated an increase in B10 percentages with higher BAFF concentrations (p = 0.041) (figure 3C). In addition, there was no difference in B10 percentages between immunosuppressed and nonimmunosuppressed patients.

Figure 3. Lower percentages of B10 cells in MuSK MG.

(A) Intracellular cytokine analysis for interleukin (IL)-10 following 48-hour stimulation with rCD40L and LPS (BFA, PMA, and ionomycin for the last 5 hours). Representative plots in a healthy control and a patient with muscle-specific tyrosine kinase (MuSK) myasthenia gravis (MG) are gated on CD19+ cells, and the numbers in the plots represent the frequency of IL-10–positive events. (B) Comparison of the mean percentages of B10 cells in healthy controls and patients with MuSK MG (n = 13; p = 0.013). (C) Comparison of B10 cell percentages and B cell–activating factor (BAFF) levels in patients with MuSK MG (p = 0.041).

DISCUSSION

MuSK MG is known to involve different IgG subtypes from AChR MG, different HLA associations and response to therapy, and reportedly fewer thymic changes. This suggests that these 2 forms of MG could have different immunopathologic mechanisms.

The cellular immunopathology of MuSK MG has not been extensively studied. In a recent study, we characterized T-cell responses in MuSK MG and found enhanced polyfunctional Th1 and Th17 responses.13 However, there was no change in Treg percentages or the expression of CD39—a proposed marker of Treg function. Thus, the mechanism of abnormal T- and B-cell homeostasis and autoreactive B cells in MuSK MG remained uncertain, and B-cell immunoregulatory mechanisms represent another important pathway.

In this study, we found no differences in the percentages of total B cells and B-cell subsets between controls and patients with MuSK not treated with rituximab. Peripheral BAFF levels were elevated in MuSK MG, as in AChR MG,28–30 but there were no changes in the percentage of B cells expressing BAFF receptor. This suggests that secreted BAFF, which is produced by myeloid lineage cells and regulates B-cell survival and growth, but not BAFF receptor expression, may be more important in promoting autoreactive B cells in MuSK MG. We observed no other distinguishing features regarding BAFF levels except in early disease, where we found the highest levels of plasma BAFF. This suggests that interventions targeting BAFF may be more effective early in the disease.

Elevated BAFF levels have been found in other autoimmune diseases, but a targeted investigation had not been performed previously in MuSK MG. BAFF is an established focus for therapeutic intervention in autoimmune diseases, and the monoclonal antibody that targets BAFF, belimumab, has been approved for the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus.31 A clinical trial of belimumab in both AChR+ and MuSK MG is currently in progress.32 Our findings support the inclusion of patients with MuSK in this trial, and it will be interesting to see whether interference with BAFF signaling has different effects on patients with AChR and MuSK MG.

Since our previous study did not find changes in Treg percentages in MuSK MG as a potential mechanism for a breakdown in self-tolerance,13 we examined another subset of regulatory cells, the B10 cells, which are characterized by the production of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10. IL-10 produced by B10 cells potently inhibits antigen-specific inflammation and T cell–dependent autoimmune diseases.33 On the other hand, elimination of B10 cells exacerbates autoimmune diseases in murine models of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, chronic colitis, collagen-induced arthritis, and lupus.16,34,35 Thus, B10 cells are increasingly recognized as vital to immune tolerance and modulating immune activation. The decreased percentages of B10 cells we found in MuSK MG could explain the previously observed increase in proinflammatory Th1 and Th17 responses and the breakdown in immune tolerance leading to the generation of autoreactive B cells in MuSK MG.13 Alternatively, IL-10 has been demonstrated to promote the generation of plasma cells, whereas BAFF enhances the survival of plasmablasts.36–39 In our study, we observed an increase in B10 cell percentages in patients with higher BAFF levels (figure 3C); however, elevated percentages of B10 cells or elevated BAFF levels did not equate to higher percentages of plasmablasts. Since the percentage of B10 cells in patients with MuSK MG is low, the small amount of IL-10 produced may be insufficient to drive plasmablast differentiation and noticeably increase their numbers.

A single previous study showed reduced B10 cell frequencies in a population of predominantly AChR MG patients who received rituximab.19 Our observation of reduced B10 cell percentages in MuSK MG is in accord with these results. That study showed that repopulation of B10 cells occurred faster in rituximab responders, who also had higher B10 cell frequencies than nonresponders. This suggests that the clinical response in MuSK MG rituximab responders could involve B10 cell–mediated suppression of the proinflammatory Th1 and Th17 responses.

Confirming a previous study in which MuSK autoantibody levels increased with MGFA severity class and clinical score,40 we found elevated levels of MuSK autoantibodies as the disease status became more severe. Whereas antibody levels are not reliable markers of disease severity, clinical status, or response to treatment in AChR autoantibody MG,41,42 autoantibody levels may be a potential biomarker for monitoring disease status in MuSK MG.

The relatively small sample size and heterogeneous treatment regimens and disease severity limit our ability to determine differential effects on B cells related to specific treatments or disease severity. Despite these limitations, this study of comprehensively characterized patients in this difficult-to-study population provides novel insights into the distinctive B-cell immunopathology in MuSK MG. Methods to identify MuSK-specific B cells, currently under development, will provide greater specificity for determining the mechanisms of MuSK MG pathology.

This study reports findings of elevated BAFF levels and decreased percentages of B10 cells in MuSK MG and supports the potential utility of MuSK antibodies as a biomarker of disease severity. BAFF-targeted therapies hold promise for MuSK MG treatment and should be further investigated. Along with a previous study of T cells, the emerging picture suggests that decreased B10 cell numbers may be critical to the loss of self-tolerance in MuSK MG. Without sufficient B10-derived anti-inflammatory IL-10, a permissive environment is created for enhanced BAFF signaling, autoantibody production, and Th1/Th17-mediated inflammation. Studies to increase the current understanding of the immunobiology of MuSK MG will require multicenter collaborations to recruit patients with this rare autoimmune disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank the Duke University Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) immunology core, an NIH-funded program (P30 AI 64518), for their guidance in the flow cytometry assays.

GLOSSARY

- AChR

acetylcholine receptor

- BAFF

B cell–activating factor

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- HLA

human leukocyte antigen

- IL

interleukin

- MG

myasthenia gravis

- MGFA

Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America

- MG-MMT

MG manual muscle testing

- MuSK

muscle-specific tyrosine kinase

- PBMC

peripheral blood mononuclear cell

- PFA

paraformaldehyde

- TPE

therapeutic plasma exchange

- Treg

regulatory T cell

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Jeffrey T. Guptill, John Yi: study conception and design, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript drafting and revision. Scuderi, Bartoccioni: data analysis and interpretation, data interpretation, manuscript drafting and revision. Guidon, Sanders, Howard, Massey, Juel, Weinhold, Evoli: study conduct, data interpretation, critical review of manuscript.

STUDY FUNDING

This study was supported by a clinician-scientist development award sponsored by the American Brain Foundation and the Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America (Dr. Guptill) and a pilot grant from the Duke Translational Research Institute (CTSA grant UL1RR024128).

DISCLOSURE

J.T. Guptill has served on the scientific advisory board for UCB Biosciences; has consulted for UCB Biosciences, Jacobus Pharmaceutical Company Inc, and Serimmune Inc; has had a fellowship in neurology clinical drug development sponsored by UCB Biosciences, UNC School of Pharmacy, Duke University, and Hamner Institutes; and has received research support from UCB Biosciences, NIH/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, Duke University, American Academy of Neurology Foundation, Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America, and Jose Antonio Grifols Lucas Foundation. J.S. Yi reports no disclosures. D.B. Sanders is on the advisory board for Alexion and Accordant Health Services; receives publishing royalties from Edshagen Publishing House; and has consulted for Cytokinetic Inc, GlasoSmithKline, Jacobus Pharmaceuticals, and UCB. A.C. Guidon receives publishing royalties from The Oakstone Institute and her husband is employed by GE Healthcare and owns GE stock. V.C. Juel receives research support from Alexion Pharmaceuticals and Jacobus Pharmaceuticals. J.M. Massey is on the AAN Board of Directors and has received unrestricted CME educational grants from Allergan and Merz. J.F. Howard, Jr. is on the board of directors for the American Board of Electrodiagnostic Medicine; is on the medical/scientific advisory board for the Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America; is on the Data Safety Monitoring Committee for Catalyst Pharmaceuticals; has consulted for Alexion Pharmaceuticals; and has received research support from Alexion Pharmaceuticals, UCB Pharmaceuticals, UCB, NIH/NIAMS, and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. F. Scuderi and E. Bartoccioni report no disclosures. A. Evoli has served on a scientific advisory board for UCB Biosciences GmbH. K.J. Weinhold reports no disclosures. Go to Neurology.org/nn for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hoch W, McConville J, Helms S, Newsom-Davis J, Melms A, Vincent A. Auto-antibodies to the receptor tyrosine kinase MuSK in patients with myasthenia gravis without acetylcholine receptor antibodies. Nat Med 2001;7:365–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Evoli A, Tonali PA, Padua L, et al. Clinical correlates with anti-MuSK antibodies in generalized seronegative myasthenia gravis. Brain 2003;126:2304–2311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanders DB, El-Salem K, Massey JM, McConville J, Vincent A. Clinical aspects of MuSK antibody positive seronegative MG. Neurology 2003;60:1978–1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guptill JT, Sanders DB. Update on muscle-specific tyrosine kinase antibody positive myasthenia gravis. Curr Opin Neurol 2010;23:530–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lauriola L, Ranelletti F, Maggiano N, et al. Thymus changes in anti-MuSK-positive and -negative myasthenia gravis. Neurology 2005;64:536–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pasnoor M, Wolfe GI, Nations S, et al. Clinical findings in MuSK-antibody positive myasthenia gravis: a U.S. experience. Muscle Nerve 2010;41:370–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guptill JT, Sanders DB, Evoli A. Anti-MuSK antibody myasthenia gravis: clinical findings and response to treatment in two large cohorts. Muscle Nerve 2011;44:36–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Niks EH, Kuks JB, Roep BO, et al. Strong association of MuSK antibody-positive myasthenia gravis and HLA-DR14-DQ5. Neurology 2006;66:1772–1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bartoccioni E, Scuderi F, Augugliaro A, et al. HLA class II allele analysis in MuSK-positive myasthenia gravis suggests a role for DQ5. Neurology 2009;72:195–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farrugia ME, Bonifati DM, Clover L, Cossins J, Beeson D, Vincent A. Effect of sera from AChR-antibody negative myasthenia gravis patients on AChR and MuSK in cell cultures. J Neuroimmunol 2007;185:136–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cole RN, Reddel SW, Gervasio OL, Phillips WD. Anti-MuSK patient antibodies disrupt the mouse neuromuscular junction. Ann Neurol 2008;63:782–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diaz-Manera J, Martinez-Hernandez E, Querol L, et al. Long-lasting treatment effect of rituximab in MuSK myasthenia. Neurology 2012;78:189–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yi JS, Guidon A, Sparks S, et al. Characterization of CD4 and CD8 T cell responses in MuSK myasthenia gravis. J Autoimmun 2013;52:130–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balandina A, Lecart S, Dartevelle P, Saoudi A, Berrih-Aknin S. Functional defect of regulatory CD4(+)CD25+ T cells in the thymus of patients with autoimmune myasthenia gravis. Blood 2005;105:735–741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thiruppathi M, Rowin J, Ganesh B, Sheng JR, Prabhakar BS, Meriggioli MN. Impaired regulatory function in circulating CD4(+)CD25(high)CD127(low/-) T cells in patients with myasthenia gravis. Clin Immunol 2012;145:209–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mauri C, Gray D, Mushtaq N, Londei M. Prevention of arthritis by interleukin 10-producing B cells. J Exp Med 2003;197:489–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsushita T, Yanaba K, Bouaziz JD, Fujimoto M, Tedder TF. Regulatory B cells inhibit EAE initiation in mice while other B cells promote disease progression. J Clin Invest 2008;118:3420–3430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carter NA, Rosser EC, Mauri C. Interleukin-10 produced by B cells is crucial for the suppression of Th17/Th1 responses, induction of T regulatory type 1 cells and reduction of collagen-induced arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 2012;14:R32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun F, Ladha SS, Yang L, et al. Interleukin-10 producing-B cells and their association with responsiveness to rituximab in myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve 2014;49:487–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jaretzki A, III, Barohn RJ, Ernstoff RM, et al. Myasthenia gravis: recommendations for clinical research standards. Task Force of the Medical Scientific Advisory Board of the Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America. Neurology 2000;55:16–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanders DB, Tucker-Lipscomb B, Massey JM. A simple manual muscle test for myasthenia gravis: validation and comparison with the QMG score. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2003;998:440–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iwata Y, Matsushita T, Horikawa M, et al. Characterization of a rare IL-10-competent B-cell subset in humans that parallels mouse regulatory B10 cells. Blood 2011;117:530–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maecker HT, McCoy JP, Nussenblatt R. Standardizing immunophenotyping for the Human Immunology Project. Nat Rev Immunol 2012;12:191–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yi JS, Decroos EC, Sanders DB, Weinhold KJ, Guptill JT. Prolonged B-cell depletion in MuSK myasthenia gravis following rituximab treatment. Muscle Nerve 2013;48:992–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anolik JH, Barnard J, Owen T, et al. Delayed memory B cell recovery in peripheral blood and lymphoid tissue in systemic lupus erythematosus after B cell depletion therapy. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:3044–3056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lesley R, Xu Y, Kalled SL, et al. Reduced competitiveness of autoantigen-engaged B cells due to increased dependence on BAFF. Immunity 2004;20:441–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thien M, Phan TG, Gardam S, et al. Excess BAFF rescues self-reactive B cells from peripheral deletion and allows them to enter forbidden follicular and marginal zone niches. Immunity 2004;20:785–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim JY, Yang Y, Moon JS, et al. Serum BAFF expression in patients with myasthenia gravis. J Neuroimmunol 2008;199:151–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ragheb S, Lisak R, Lewis R, Van Stavern G, Gonzales F, Simon K. A potential role for B-cell activating factor in the pathogenesis of autoimmune myasthenia gravis. Arch Neurol 2008;65:1358–1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scuderi F, Alboini PE, Bartoccioni E, Evoli A. BAFF serum levels in myasthenia gravis: effects of therapy. J Neurol 2011;258:2284–2285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Furie R, Petri M, Zamani O, et al. A phase III, randomized, placebo-controlled study of belimumab, a monoclonal antibody that inhibits B lymphocyte stimulator, in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63:3918–3930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study to evaluate the efficacy, safety, tolerability, and pharmacodynamics of belimumab in subjects with generalized myasthenia gravis (MG). ClinicalTrials.gov Web site. Available at: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01480596?term=belimumab&rank=35. Accessed May 6, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mauri C, Bosma A. Immune regulatory function of B cells. Annu Rev Immunol 2012;30:221–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fillatreau S, Sweenie CH, McGeachy MJ, Gray D, Anderton SM. B cells regulate autoimmunity by provision of IL-10. Nat Immunol 2002;3:944–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Watanabe R, Ishiura N, Nakashima H, et al. Regulatory B cells (B10 cells) have a suppressive role in murine lupus: CD19 and B10 cell deficiency exacerbates systemic autoimmunity. J Immunol 2010;184:4801–4809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Agematsu K, Nagumo H, Oguchi Y, et al. Generation of plasma cells from peripheral blood memory B cells: synergistic effect of interleukin-10 and CD27/CD70 interaction. Blood 1998;91:173–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Avery DT, Kalled SL, Ellyard JI, et al. BAFF selectively enhances the survival of plasmablasts generated from human memory B cells. J Clin Invest 2003;112:286–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moisini I, Davidson A. BAFF: a local and systemic target in autoimmune diseases. Clin Exp Immunol 2009;158:155–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heine G, Drozdenko G, Grun JR, Chang HD, Radbruch A, Worm M. Autocrine IL-10 promotes human B-cell differentiation into IgM- or IgG-secreting plasmablasts. Eur J Immunol 2014;44:1615–1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bartoccioni E, Scuderi F, Minicuci GM, Marino M, Ciaraffa F, Evoli A. Anti-MuSK antibodies: correlation with myasthenia gravis severity. Neurology 2006;67:505–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Drachman DB, Adams RN, Josifek LF, Self SG. Functional activities of autoantibodies to acetylcholine receptors and the clinical severity of myasthenia gravis. N Engl J Med 1982;307:769–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sanders DB, Burns TM, Cutter GR, et al. Does change in acetylcholine receptor antibody level correlate with clinical change in myasthenia gravis? Muscle Nerve 2014;49:483–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]