Abstract

Oxidized LDL (oxLDL) performs critical roles in atherosclerosis by inducing macrophage foam cell formation and promoting inflammation. There have been reports showing that oxLDL modulates macrophage cytoskeletal functions for oxLDL uptake and trapping, however, the precise mechanism has not been clearly elucidated. Our study examined the effect of oxLDL on non-muscle myosin heavy chain IIA (MHC-IIA) in macrophages. We demonstrated that oxLDL induces phosphorylation of MHC-IIA (Ser1917) in peritoneal macrophages from wild-type mice and THP-1, a human monocytic cell line, but not in macrophages deficient for CD36, a scavenger receptor for oxLDL. Protein kinase C (PKC) inhibitor-treated macrophages did not undergo the oxLDL-induced MHC-IIA phosphorylation. Our immunoprecipitation revealed that oxLDL increased physical association between PKC and MHC-IIA, supporting the role of PKC in this process. We conclude that oxLDL via CD36 induces PKC-mediated MHC-IIA (Ser1917) phosphorylation and this may affect oxLDL-induced functions of macrophages involved in atherosclerosis. [BMB Reports 2015; 48(1): 48-53]

Keywords: Atherosclerosis, CD36, Macrophage, Non-muscle myosin, Oxidized LDL

INTRODUCTION

There have been extensive studies proving that low-density lipoprotein (LDL) is oxidatively modified in vivo and this modification provokes proinflammatory and proatherogenic responses (1-4). Oxidative modification increases atherogenicity of LDL by facilitating uptake and retention of circulating LDL in the arterial wall. Oxidized LDL (oxLDL) induces adhesion molecule expression in endothelial cells, cytokine secretion by monocytes/macrophages, and smooth muscle cell proliferation, which are hallmarks of the atherosclerotic process (5-9). Macrophages internalize oxLDL via scavenger receptors including CD36 and scavenger receptor A (SRA) and turn into foam cells that recruit inflammatory cell infiltrates into the arterial wall (10). However, the precise mechanism for oxLDL uptake has not been completely defined. OxLDL is also known to induce endothelial dysfunction (11). Alterations in the structural and functional integrity of the endothelial barrier allow a net influx of LDL from the circulation into the subendothelial space. However, the mechanism by which oxLDL induces endothelial dysfunction has not been fully defined.

The cytoskeleton is a cellular network of structural, signaling, and adaptor molecules that regulate most cellular functions such as migration, ligand recognition, signal activation and endocytosis/phagocytosis (12). There have been reports that oxLDL affects the cytoskeletal functions of various cell types involved in atherosclerosis. OxLDL drives endothelial cell stiffness and increases pinocytotic activity of endothelial cells through cytoskeletal reorganization (13-15). In macrophages, oxLDL facilitates actin polymerization and spreading and this process inhibits macrophage migration, promoting macrophage trapping (16, 17). In our recent report, oxLDL via CD36 was shown to inhibit macrophage migration through loss of cell polarity by inhibiting non-muscle myosin II (NMII) activity (18). Therefore, the cytoskeletal modulating activity of oxLDL should be a key mechanism that drives cellular dysfunction.

Myosins are molecular motor proteins that crosslink and translocate actin filaments, using energy from ATP hydrolysis. NMII molecules are composed of three pairs of peptides including two heavy chains of 230 kDa, two regulatory light chains (RLC) of 20 kDa, which are known to regulate NMII activity, and two 17 kDa essential light chains stabilizing the heavy chain structure (19, 20). NMII regulates cellular protrusion, polarity, migration and integrin-mediated adhesion (21-23). In addition to the motor function of NMII, the newly recognized functions of NMII involve internalization of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and the downstream signaling provoked by EGFR (24) and maturation of the immunological synapse (25), suggesting more diverse functions of NMII that warrant investigation.

NMII activity and the assembly of NMII filaments are known to be regulated by RLC phosphorylation, which is controlled by small molecular weight G proteins such as Rho and Rac (26). Whereas roles of RLC phosphorylation have been extensively studied, roles of phosphorylation events on non-muscle myosin heavy chain (MHC) have not been characterized.

In the current study, we demonstrate that interaction between oxLDL and CD36 induces MHC-IIA phosphorylation in macrophages and the MHC-IIA phosphorylation is mediated by protein kinase C (PKC). We expect that this finding may underly a crucial mechanism by which CD36 mediates uptake of oxLDL and provokes subsequent signaling for pro-inflammatory action. This also suggests an additional mechanism for macrophage trapping in atherosclerotic inflammatory lesions.

RESULTS

OxLDL induces MHC phosphorylation (Ser1917)

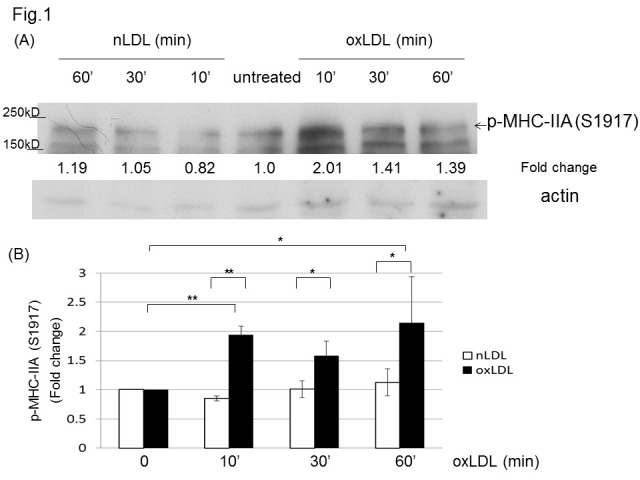

Based on our previous report showing that oxLDL inhibits NMII activity by dephosphorylating RLC (Thr18/Ser19), and that NMIIA is the dominant isoform expressed in macrophages (18), we tested if oxLDL affects MHC phosphorylation. Western blot detection of phosphorylated MHC-IIA (Ser1917) showed that oxLDL induced a significant increase in MHC-IIA phosphorylation (Ser1917), while native LDL (nLDL) did not induce an effect in murine peritoneal macrophages (Fig. 1). Another MHC-IIA residue (Ser1948) known to be phosphorylated by casein kinase 2 (CK2) (27) was not affected by oxLDL in our western blot analysis (data not shown).

Fig. 1. OxLDL induces phosphorylation of MHC-IIA (Ser1917) in macrophages. (A) Murine peritoneal macrophages were treated with or without nLDL (50 μg/ml) or oxLDL (50 μg/ml) for the indicated times and the cell lysates were analyzed by western blotting to detect phospho-MHC-IIA (Ser1917). Levels of p-MHC-IIA (Ser1917) were normalized to β-actin and are expressed as fold increases relative to the control (untreated macrophages) arbitrarily set at 1 (100%). (B) Quantitative analysis for the Western blots in (A). Scale bars are mean ± S.E.M. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, (Student’s t-test). The western blot was repeated three times.

OxLDL-induced MHC phosphorylation (Ser1917) depends on CD36

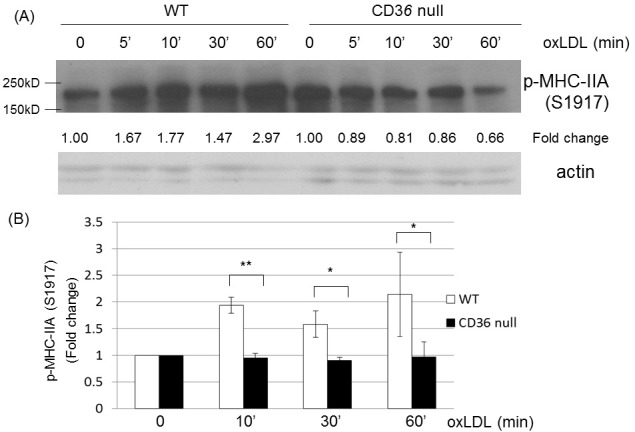

We tested if oxLDL-induced MHC phosphorylation (Ser1917) is mediated by CD36. We incubated peritoneal macrophages isolated from wild-type and Cd36 null mice with oxLDL and analyzed the cell lysates by western blotting for phosphorylated MHC-IIA (Ser1917). Our Western blot analysis showed that oxLDL did not induce MHC-IIA phosphorylation (Ser1917) in Cd36 null macrophages, while there was MHC-IIA phosphorylation (Ser1917) in wild-type macrophages in response to oxLDL (Fig. 2). The results suggest that oxLDL-induced phosphorylation of MHC is mediated by CD36.

Fig. 2. OxLDL-induced phosphorylation of MHC-IIA (Ser1917) depends on CD36. (A) Peritoneal macrophages from wild-type and Cd36 null mice were treated with oxLDL (50 μg/ml) for indicated times and the cell lysates were analyzed by western blotting to detect phospho-MHC-IIA (Ser1917). Levels of p-MHC-IIA (Ser1917) were normalized to β-actin and are expressed as fold increases relative to the control (untreated macrophages) arbitrarily set at 1 (100%). (B) Quantitative analysis of the Western blots in (A). Scale bars are mean ± S.E.M. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, (Student’s t-test). The western blot was repeated three times.

OxLDL-induced MHC phosphorylation (Ser1917) is mediated by protein kinase C (PKC)

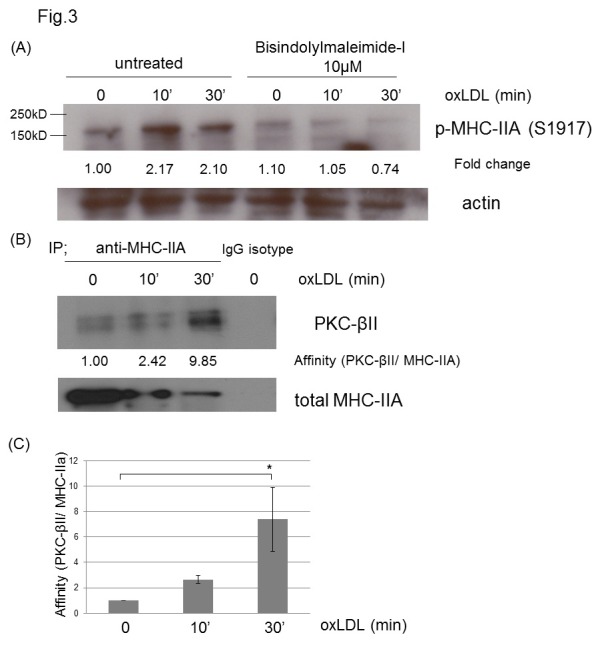

Previous reports have shown that MHC-IIA (Ser1917) phosphorylation is mediated by PKC (28, 29) and oxLDL activates PKC in macrophages (30, 31). To test if PKC is involved in MHC-IIA phosphorylation (Ser1917) by oxLDL, we blocked PKC activation by using bisindolylmaleimide-I (GF109203X), which is known to inhibit PKC. Our data revealed that PKC inhibitor-treated macrophages did not show oxLDL-induced MHC phosphorylation (Ser1917), while untreated macrophages had an oxLDL-induced increase in phospho-MHC-IIA (Ser1917) (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3. OxLDL-induced phosphorylation of MHC-IIA (Ser1917) is mediated by PKC. (A) Murine peritoneal macrophages untreated or pre-treated with bisindolylmaleimide-I (10 μM) were treated with or without oxLDL (50 μg/ml) for the indicated times. The cell lysates were analyzed by westen blot to detect phospho-MHC-IIA (Ser1917). Levels of p-MHC-IIA (Ser1917) were normalized to β-actin and are expressed as fold increases relative to the control (untreated macrophages)arbitrarily set at 1 (100%). (B) MHC-IIA protein was pulled down from murine macrophages incubated with or without oxLDL (50 μg/ml) for the indicated times using anti-MHC-IIA antibody. The immunoprecipitates were separated by SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis and blotted for PKC-βII detection. (C) Quantitative analysis of the immunoprecipitation experiments performed as in (B). Affinity between MHC-IIA and PKC-βII was calculated and plotted in the graph. Scale bars are mean ± S.E.M. *P < 0.05 (Student’s t-test). The experiment was repeated three times.

Based on the report showing that MHC IIA is phosphorylated (Ser 1917) by PKC-βII in mast cells (29), we tested if PKC-βII mediates MHC-IIA phosphorylation in macrophages. We used immunoprecipitation to evaluate changes in the physical association between MHC-IIA and PKC-βII. Our data revealed that oxLDL increased the physical association between MHC-IIA and PKC-βII by 9.8-fold (Fig. 3B) suggesting the involvement of PKC-βII in the MHC-IIA phosphorylation.

OxLDL induced MHC phosphorylation (Ser 1916) in THP-1 cells

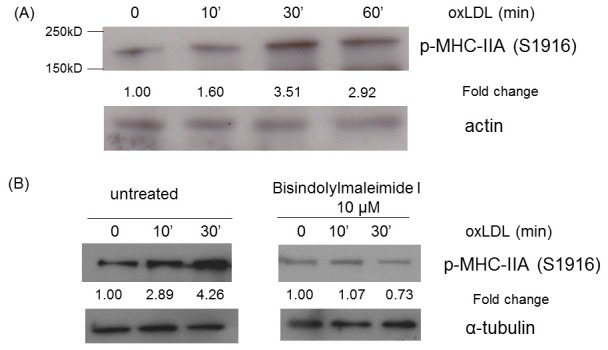

We tested if oxLDL-induced MHC-IIA phosphorylation occurs in the human monocytic cell line, THP-1. THP-1 cells that had differentiated into macrophage-like cells were incubated with oxLDL and the cell lysates were analyzed by western blot for phospho-MHC IIA (Ser1916), which is the Ser1917-accordant site for human MHC-IIA. The Western blot analysis confirmed that oxLDL induced a 3-fold increase in phospho-MHC-IIA (Ser 1916) in THP-1-derived macrophage-like cells (Fig. 4A). As shown in murine macrophages, bisindolylmaleimide-I treatment blocked the oxLDL-induced phosphorylation of MHC-IIA (Ser 1916) in THP-1-derived macrophage-like cells (Fig. 4B), confirming the involvement of PKC.

Fig. 4. OxLDL induced phosphorylation of MHC-IIA (Ser1917) in THP-1 cells. (A) THP-1 cells differentiated into macrophage-like cells were untreated or treated with oxLDL (50 μg/ml) for indicated times and the cell lysates were analyzed by western blotting to detect phospho-MHC-IIA (Ser1916). Levels of p-MHC-IIA (Ser1916) were normalized to β-actin and are expressed as fold increases relative to the control (untreated macrophages) arbitrarily set at 1 (100%). (B) THP-1 cells differentiated into macrophage-like cells were pre-treated (left panels) and untreated (right panels) with bisindolylmaleimide-I (10 μM) and exposed to oxLDL (50 μg/ml) for indicated times. Western blotting for phospho-MHC-IIA (Ser1916) was performed with the cell lysates. Levels of p-MHC-IIA (Ser1916) were normalized to β-actin and are expressed as fold increases relative to the control (untreated macrophages) arbitrarily set at 1 (100%).

DISCUSSION

OxLDL resides in the subendothelial space of atherosclerotic arteries and in plasma of patients with metabolic disorders (32-35), performing various pathological functions. Therefore, understanding the role of oxLDL may help define the pathophysiology of the metabolic diseases including atherosclerosis, and provide a new therapeutic strategy.

CD36 is a class B scavenger receptor expressed in various cell types including monocyte/macrophages, endothelial cells, platelets and adipocytes (36, 37). In atherosclerosis, CD36 mediates macrophage oxLDL uptake and promotes pro-inflammatory functions. CD36-mediated signaling events, including activation of src kinases and mitogen-activated protein kinases, mediate the internalization of oxLDL (38, 39). However, the question of which molecule is used as the cargo for the oxLDL transport, remains unclear. There have been obvious discrepancies in studies of the oxLDL uptake mechanism. One of the widely accepted views for the oxLDL uptake mechanism is that oxLDL is internalized through macropinocytosis. This is based on a previous observation that modified LDL is associated with ruffles and resides in macropinosomes of macrophages (40). However, Zeng et al. (41) showed that internalized oxLDL and CD36 were found in moderately-sized cytoplasmic structures co-localizing with a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored protein, suggestive of uptake via lipid raft endocytosis. Moreover, Sun et al. (42) reported that oxLDL uptake by CD36 is independent of actin, but depends on dynamin. However, Trimble et al. demonstrated an actin dependency of the oxLDL uptake, which is distinct from macropinocytosis (39). Regarding the critical functions of foam cells in the atherogenic process, elucidation of the oxLDL uptake mechanism should be a primary focus of future studies.

Our current study reveals that oxLDL via CD36 induces phosphorylation of MHC-IIA (Ser1917). Unlike RLC phosphorylation, there have been few reports elucidating the roles of MHC phosphorylation. Various phosphorylation sites have been identified near the C-termini of MHCs, in both the coiled-coil domain and the non-helical tail, including sites that are phosphorylated by PKC (43), CK2 (27, 44) and transient receptor potential melastatin 7 (TRPM7) (45). MHC phosphorylation in each residue has been shown to dissociate myosin filaments or prevent filament formation in vitro. MHC phosphorylation (Ser1917) by PKC inhibits the assembly of NMIIA rods into filaments (44). Intriguingly, PKC-βII-induced MHC phosphorylation (Ser 1917) contributes to exocytosis in mast cells (29). In our data, oxLDL increases physical association between MHC-IIA and PKC-βII (Fig. 3B), suggesting involvement of a PKC-βII. As mast cells, macrophages secrete various cytokines in response to oxLDL, and thus, it may be worthwhile to test possible roles of MHC phosphorylation in macrophage exocytosis.

Recent studies of NMII have revealed that NMII is involved in various cellular functions beyond serving as a structural protein in cytoskeletal arrangement. Kim et al. showed that NMII mediates internalization of EGFR and the downstream signaling including ERK and Akt activation (24). In addition, experimental results have revealed that NMII interacts with several kinds of receptors including CXCR4 (chemokine receptor), N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor, DDR1 (a collagen receptor), and the inositol 1,4,5, triphosphate (P3) receptor (46-49). Therefore, interaction between CD36 and NMII and the role of NMII in CD36-mediated oxLDL uptake and downstream signaling are intriguing topics to study in the future. Roles of MHC-IIA phosphorylation in macrophages should be explored due to the potential involvement in various oxLDL-derived functions, however, transfection of primary macrophages with mutant MHC-IIA and suppression of endogenous MHC-IIA expression appear to be technically challenging at this time.

We recently reported that oxLDL via CD36 inhibits macrophage migration by modulating cytoskeletal function (17, 18), and suggested that oxLDL facilitates macrophage spreading and actin polymerization but inhibits migration via dysregulated activation of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) (17). In addition, oxLDL via CD36 induces loss of macrophage cell polarity by inhibiting the activity of NMIIA (18). OxLDL-induced inhibition of macrophage migration may explain the mechanism of macrophage trapping in atherosclerotic inflammation. Defining the mechanism of macrophage trapping and promoting macrophage egress may be a new therapeutic strategy for the treatment of atherosclerosis. Therefore, we suggest an additional mechanism for macrophage trapping involving MHC-IIA phosphorylation, another way for oxLDL to induce disassembly of myosin filaments.

Our current study demonstrates oxLDL-induced MHC-IIA phosphorylation in murine and human macrophages, suggesting a new function for the cytoskeletal modulating effect of oxLDL and providing new insights into the pathology of atherosclerosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

LDL was prepared from human plasma by density gradient ultracentrifugation (50). Oxidatively modified LDL (Cu2+ oxLDL) was generated by dialysis of LDL with 5 μM CuSO4 in PBS for 6 hours at 37℃. Oxidation was terminated by dialysis against PBS containing 100 μM EDTA. Bisindolylmaleimide-I (GF 109203X) was purchased from Sigma. Antibodies for MHC-IIA, PKC-βII and β-actin were purchased from SantaCruz Biotechnology. Antibodies for the detection of phospho-MHC-IIA (Ser1917, in human, Ser1916) and MHC-IIA (Ser1948) were provided by Dr. Thomas Egelhoff at the Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland Clinic.

Cell culture

We collected peritoneal macrophages from C57BL/6 mice and Cd36 null mice provided by Dr. Roy L. Silverstein at the Medical College of Wisconsin, by peritoneal lavage 4 days after intraperitoneal injection of 4% thioglycolate (1 ml). Cells were cultured in RPMI containing 10% fetal bovine serum. The human monocyte cell line THP-1 was obtained from ATCC and were treated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (200 nM) for 1 day and then cultured in RPMI containing fetal bovine serum (10%) for 5 days for macrophage differentiation.

Western blot analysis and immunoprecipitation

Mouse peritoneal macrophages incubated with 50 μg/ml oxLDL for the indicated times were lysed in a buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% NP-40, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM β-glycerophosphate, and 1 mM sodium orthovanadate. Clarified lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore). Membranes were probed with antibodies against p-MHC-IIA (Ser1917). After chemiluminescence detection, membranes were stripped with 0.2 M sodium hydroxide and reprobed with antibodies against β-actin for normalization. Band intensities were quantified by ImageJ (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/) and Gel-Pro Analyzer (MediaCybernetics). For immunoprecipitation, macrophages incubated with or without oxLDL (50 μg/ml) were lysed using the buffer described above and the cell lysate containing 500 μg of protein was incubated with 3 μg of anti-MHC-IIA antibody immobilized on agarose beads overnight at 4℃. Beads were extensively washed and boiled in SDS-PAGE loading buffer and the bound material was analyzed by immunoblot using an antibody for PKC-βII. The affinity between MHC-IIA and PKC-βII was calculated by the band intensity of PKC-βII divided by the band intensity of MHC-IIA. All Western blot analyses were repeated 3 times.

Statistics

We performed ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test. A P value less than 0.05 was considered significant. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD. Analyses were formed using GraphPad Prism Software.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Dr. Eun-Suk Kang at the Department of Laboratory Medicine and Genetics, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea, for providing human plasma for LDL preparation. This work was supported by the Ewha Womans University Research Grant of 2011 and in part by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) Grant funded by the Korean Government (MSIP)(No. NRF-2012R1A1A1013250).

References

- 1.Steinbrerg D, Parthasarathy S, Carew TE, Khoo JC, Witztum JL. Beyond cholesterol. Modifications of low-density lipoprotein that increase its atherogenicity. N Engl J Med. (1989);320:915–924. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198904063201407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steinbrecher UP. oxidation of human low density lipoprotein results in derivatization of lysine residues of apolipoprotein B by lipid peroxide decomposition products. J Biol Chem. (1987);262:3603–3608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stocker R, Keaney KJ., Jr New insights on oxidative stress in the artery wall. J Throm Haem. (2005);3:1825–1834. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stocker R, Keaney JF., Jr Role of oxidative modifications in atherosclerosis. Physiol Rev. (2004);84:1381–1478. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00047.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rajavashisth TB, Andalibi A, Territo MC, et al. Induction of endothelial cell expression of granulocyte and macrophage colony-stimulating factors by modified low density lipoproteins. Nature (London) (1990);344:254–257. doi: 10.1038/344254a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cushing SD, Berliner JA, Valente AJ, et al. Minimally modified low density lipoprotein inducesmonocyte chemotactic protein 1 in human endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (1990);87:5134–5138. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.13.5134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carlos TM, Harlan JM. Membrane proteins involved in phagocyte adherence to endothelium. Immunol Rev. (1990);114:5–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.1990.tb00559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khan BV, Parthasarathy SS, Alexander RW, Medford RM. Modified low density lipoprotein and its constituents augment cytokine-activated vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 gene expression in human vascular endothelial cells. J Clin Invest. (1995);95:1262–1270. doi: 10.1172/JCI117776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chatterjee S, Ghosh N. Oxidized low density lipoprotein stimulates aortic smooth muscle cell proliferation. Glycobiology. (1996);6:303–311. doi: 10.1093/glycob/6.3.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown MS, Goldstein JL. Atherosclerosis. Scavenging for receptors. Nature. (1990);343:508–509. doi: 10.1038/343508a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salonen JT, Nyyssonen K, Salonen R, et al. Lipoprotein oxidation and progression of carotid atherosclerosis. Circulation. (1997);95:840–845. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.95.4.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duden R, Ho WC, Allan VJ, Kreis TE. What's new in cytoskeleton-organelle interactions? Relationship between microtubules and the Golgi-apparatus. Pathol Res Pract. (1990);186:535–541. doi: 10.1016/S0344-0338(11)80478-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao B, Ehringer WD, Dierichs R, Miller FN. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein increases endothelial intracellular calcium and alters cytoskeletal f-actin distribution. Eur J Clin Invest. (1997);27:48–54. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.1997.750628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chouinard JA, Grenier G, Khalil A, Vermette P. Oxidized-LDL induce morphological changes and increase stiffness of endothelial cells. Exp Cell Res. (2008);314:3007–3016. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chow S, Lee R, Shih SH, Chen J. Oxidized LDL promotes vascular endothelial cell pinocytosis via a prooxidation mechanism. FASEB J. (1998);12:823–830. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.10.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller YI, Worrall DS, Funk CD, Feramisco JR, Witztum JL. Actin polymerization in macrophages in response to oxidized LDL and apoptotic cells: Role of 12/15-Lipoxygenase and Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase. Mol Biol Cell. (2003);14:4196–4206. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-02-0063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park YM, Febbraio M, Silverstein RL. CD36 modulates migration of mouse and human macrophages in response to oxidized LDL and may contribute to macrophage trapping in the arterial intima. J Clin Invest. (2009);119:136–145. doi: 10.1172/JCI35535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park YM, Drazba JA, Vasanji A, Egelhoff T, Febbraio M, Silverstein RL. Oxidized LDL/CD36 interaction induces loss of cell polarity and inhibits macrophage locomotion. Mol Biol Cell. (2012);23:3057–3068. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-12-1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clark K, Langeslag M, Figdor CG, van Leeuwen FN. Myosin II and mechanotransduction: a balancing act. Trends Cell Biol. (2007);17:178–186. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Conti MA, Adelstein RS. Nonmuscle myosin II moves in new directions. J Cell Sci. (2008);121:11–18. doi: 10.1242/jcs.007112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vicente-Manzanares M, Zareno J, Whitmore L, Choi CK, Horwitz AF. Regulation of protrusion, adhesion dynamics, and polarity by myosin IIA and IIB in migrating cells. J Cell Biol. (2007);176:573–580. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200612043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choi CK, Vicente-Manzanares M, Zareno J, Whitmore LA, Mogilner A, Horwitz AR. Actin and α-actinin orchestrate the assembly and maturation of nascent adhesions in a myosin II motor-independent manner. Nat Cell Biol. (2008);10:1039–1050. doi: 10.1038/ncb1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosado LA, Horn TA, McGrath SC, Cotter RJ, Yang JT. Association between α4 integrin cytoplasmic tail and non-muscle myosin IIA regulates cell migration. J Cell Sci. (2011);124:483–492. doi: 10.1242/jcs.074211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim JH, Wang A, Conti MA, Adelstein RS. Nonmuscle myosin II is required for internalization of the epidermal growth factor receptor and modulation of downstream signaling. J Biol Chem. (2012);287:27345–27358. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.304824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumari S, Vardhana S,, Cammer M, et al. T lymphocyte myosin IIA is required for maturation of the immunological synapse. Front Immunol. (2012);3 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00230. article 230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Somlyo AP, Somlyo AV. Ca2+ sensitivity of smooth muscle and nonmuscle myosin II: modulated by G proteins, kinases, and myosin phosphatase. Physiol Rev. (2008);83:1325–1358. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00023.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dulyaninova NG, House RP, Betapudi V, Bresnick AR. Myosin-IIA heavy-chain phosphorylation regulates the motility of MDA-MB-231 carcinoma cells. Mol Biol Cell. (2007);18:3144–3155. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-11-1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Straussman R, Even L, Ravid S. Myosin II heavy chain isoforms are phosphorylated in an EGF-dependent manner: involvement of protein kinase C. J Cell Sci. (2001);114:3047–3057. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.16.3047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ludowyke RI, Elgundi Z, Kranenburg T, et al. Phosphorylation of nonmuscle myosin heavy chain IIA on Ser1917 is mediated by protein kinase C beta II and coincides with the onset of stimulated degranulation of RBL-2H3 mast cells. J Immunol. (2006);177:1492–1499. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.3.1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsumura T, Sakai M, Kobori S, et al. Two intracellular signaling pathways for activation of protein kinase C are involved in oxidized low-density lipoprotein-induced macrophage growth. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. (1997);17:3013–3020. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.17.11.3013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feng J, Han J, Pearce SFA, et al. Induction of CD36 expression by oxidized LDL and IL-4 by a common signaling pathway dependent on protein kinase C and PPAR-γ. J Lipid Res. (2000);41:688–696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Witzum JL, Steinberg D. The oxidative modification hypothesis of atherosclerosis: Does it hold for humans? Trends Cardiovasc Med. (2001);11:93–102. doi: 10.1016/S1050-1738(01)00111-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yla-Herttuala S. Is oxidized low-density lipoprotein present in vivo? Curr Opin Lipidol. (1998);9:337–344. doi: 10.1097/00041433-199808000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Itabe H, Yamamoto H, Imanaka T, et al. Sensitive detection of oxidatively modified low density lipoprotein using a monoclonal antibody. J Lipid Res. (1996);37:45–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsimikas S. Oxidative biomarkers in the diagnosis and prognosis of cardiovascular disease. Am J cardiol. (2006);98:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Silverstein RL, Li W, Park YM, Rahaman SO. Mechanisms of cell signaling by the scavenger receptor CD36; Implications in atherosclerosis and thrombosis. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. (2010);121:206–220. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Park YM. CD36, a scavenger receptor implicated in atherosclerosis. Exp Mol Med. (2014);46:e99. doi: 10.1038/emm.2014.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rahaman SO, Lennon DJ, Febbraio M, Podrez EA, Hazen SL, Silverstein RL. A CD36-dependent signaling cascade is necessary for macrophage foam cell formation. Cell Metab. (2006);4:211–221. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Collins RF, Touret N, Kuwata H, Tandon NT, Grinstein S, Trimble WS. Uptake of oxidized low density lipoprotein by CD36 occurs by an actin-dependent pathway distinct from macropinocytosis. J Biol Chem. (2009);284:30288–30297. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.045104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jones NL, Willingham MC. Modified LDLs are internalized by macrophages in part via macropinocytosis. Anat Rec. (1999);255:57–68. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(19990501)255:1<57::AID-AR7>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zeng Y, Tao N, Chung KN, Heuser JE, Lublin DM. Endocytosis of oxidized low density lipoprotein through scavenger receptor CD36 utilizes a lipid raft pathway that does not require caveolin-1. J Biol Chem. (2003);278:45931–45936. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307722200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sun B, Boyanovsky BB, Connelly MA, Shridas P, van der Westhuyzen DR, Webb NR. Distinct mechanisms for OxLDL uptake and cellular trafficking by class B scavenger receptors CD36 and SR-BI. J Lipid Res. (2007);48:2560–2570. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700163-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Even-Faitelson L, Ravid S. PAK1 and aPKCzeta regulate myosin II-B phosphorylation: a novel signaling pathway regulating filament assembly. Mol Biol Cell. (2006);17:2869–2881. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-11-1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dulyaninova NG, Malashkevich VN, Almo SC, Bresnick AR. Regulation of myosin-IIA assembly and Mts1 binding by heavy chain phosphorylation. Biochemistry. (2005);44:6867–6876. doi: 10.1021/bi0500776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clark K, Middelbeek J, Lasonder E, et al. TRPM7 regulates myosin IIA filament stability and protein localization by heavy chain phosphorylation. J Mol Biol. (2008);378:790–803. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.02.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bajaj G, Zhang Y, Schimerlik MI, et al. N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor subunits are non-myosin targets of myosin regulatory light chain. J Biol Chem. (2009);284:1252–1266. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801861200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hours MC, Mery L. The N-terminal domain of the type 1 Ins(1,4,5)P3 receptor stably expressed in MDCK cells interacts with myosin IIA and alters epithelial cell morphology. J Cell Sci. (2010);123:1449–1459. doi: 10.1242/jcs.057687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huang Y, Arora P, McCulloch CA, Vogel WF. The collagen receptor DDR1 regulates cell spreading and motility by associating with myosin IIA. J Cell Sci. (2009);122:1637–1646. doi: 10.1242/jcs.046219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rey M, Valenzuela-Fernández A, Urzainqui A, et al. Myosin IIA is involved in the endocytosis of CXCR4 induced by SDF-1α. J Cell Sci. (2007);120:1126–1233. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hatch FT. Practical methods for plasma lipoprotein analysis. Adv Lipid Res. (1968);6:1–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]