Abstract

Introduction:

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided fine-needle aspiration (FNA) is frequently used to sample intra-abdominal lesions and lymph nodes. Celiac ganglia normally located near the celiac artery may be sampled during these procedures. The aim of this study was to determine the frequency of detection and cytologic findings of celiac ganglia diagnosed on FNA.

Materials and Methods:

A 14-year retrospective review of radiologic and endoscopic FNA cases involving the celiac region was performed. Cases in which ganglia were reported were further analyzed and slides reviewed.

Results:

A total of 354 patients underwent FNA of a suspected celiac lymph node (334 patients) or celiac mass (20 cases). In 9 of these patients (2.5%), ganglion cells were identified. These were identified in cases only after 2008 via EUS-guided FNA. Aspirates were hypocellular and bloody. Large ganglion cells were either sparsely dispersed or present in clusters. Ganglion cells had a low N: C ratio, granular cytoplasm with neuromelanin, and eccentric small round nucleus with a prominent nucleolus. One specimen had concomitant pancreatic adenocarcinoma. None of these cases had a false positive on-site adequacy assessment or final misdiagnosis.

Conclusions:

These data show that celiac ganglia may be infrequently encountered, especially with intra-abdominal EUS-guided FNA targeting nodes or masses near the celiac region. Therefore, cytologists should be aware of the possibility of finding ganglionic cells in EUS-guided FNA samples.

Keywords: Celiac, cytology, endoscopic ultrasound, fine-needle aspiration, ganglion

INTRODUCTION

The celiac ganglia innervate several intra-abdominal viscera.[1] They are located at the origin of the celiac artery, anterolateral to the aorta. There may be one to five ganglia per individual, with reported sizes ranging from 0.5 to 4.5 cm.[2] The celiac lymph nodes, located in close proximity to the celiac ganglia, are routinely evaluated during the work up for malignancy. These nodes may be biopsied using percutaneous computerized tomography (CT) or intra-abdominal endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) guided fine-needle aspiration (FNA). EUS-guided FNA is gaining wider acceptance as the primary tool for evaluating abdominal lymphadenopathy and deep-seated lesions in proximity to the gastrointestinal tract.[3]

The celiac ganglia may be difficult to distinguish from celiac lymph nodes by CT or ultrasound imaging, and thus may be sampled during FNA evaluation of the celiac lymph nodes.[4] Few studies have described the cytomorphologic features of celiac ganglia.[5,6,7] However, to the best of our knowledge, there have been no reports about the frequency of celiac ganglia diagnosed by FNA. The aim of this study was to determine the frequency of detection and to characterize the cytologic findings of celiac ganglia diagnosed by image-guided FNA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

After obtaining Institutional Review Board approval, our pathology database was retrospectively searched for all image-guided FNA cases involving the celiac region over a 14-year period (2000–2014). Only cases in which ganglion material was reported were further analyzed. All the celiac cases were not re-examined. Patient and clinical details in this subset of cases were documented, and all cytology slides reviewed. Per our standard protocol, all biopsies were performed by a radiologist or radiology physician assistant for CT or ultrasound-guided FNAs, or a gastroenterologist with training in endoscopy to perform EUS-guided FNA. In addition, these cases are routinely evaluated by the cytopathology team for immediate assessment of adequacy. At the time of the on-site evaluation, direct aspirate smears were prepared to make air dried and alcohol fixed slides. Air-dried smears were stained with Diff-Quik and alcohol fixed slides with the Papanicolaou stain. Cell blocks fixed in formalin were also made and sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and if needed utilized for immunohistochemistry.

RESULTS

Study population

During the study period, a total of 354 patients underwent FNA of a targeted area in the intra-abdominal celiac region. Celiac lymph nodes were targeted in 334 (95%) patients and in 20 (5%) cases, FNA was used to sample a celiac mass. Ganglion cells were identified in only 9 (2.5%) of these patients and these were all seen in EUS-guided FNA cases performed after 2008. These 9 patients (5 male, 4 female) were of average age 72 years (range: 57–85 years). FNA in these 9 cases specifically targeted a suspected celiac lymph node (7 cases; 80%), celiac axis soft tissue mass (1 case), and in one patient a supposed ganglion that measured 5 mm × 3 mm on imaging (1 case). The patient with a mass around the celiac axis presented with marked abdominal pain after a Whipple procedure for pancreatic cancer. None of these cases had a false positive on-site adequacy assessment or final misdiagnosis.

Cytologic findings

The aspirates in the 9 reviewed cases were mostly hypocellular, bloody, and had no lymphoid elements. Large epithelioid shaped ganglion cells were seen either sparsely dispersed [Figure 1] or cohesive in clusters [Figure 2]. When clustered the ganglion cells had a tendency to be more peripheral in these groups while nerve fibers were more central. The ganglion cells had low N:C ratios, granular cytoplasm with neuromelanin, and eccentric small round nuclei with prominent nucleoli. With the Papanicolaou stain, ganglion cell cytoplasm stained light blue/green with coarse brown granules [Figure 3]. With Diff-Quik, the pigmented granules were dark blue-purple. Nerve fibers consisted of wavy spindled cells [Figure 4]. On cell block, ganglion cells had similar voluminous pink cytoplasm and blue coarse granules [Figure 5]. Immunohistochemistry performed in one case showed S100 positivity of the ganglion tissue [Figure 6]. The patient who presented with a recurrent celiac axis mass after pancreatic surgery had concomitant pancreatic adenocarcinoma and ganglion cells in the FNA [Figure 7].

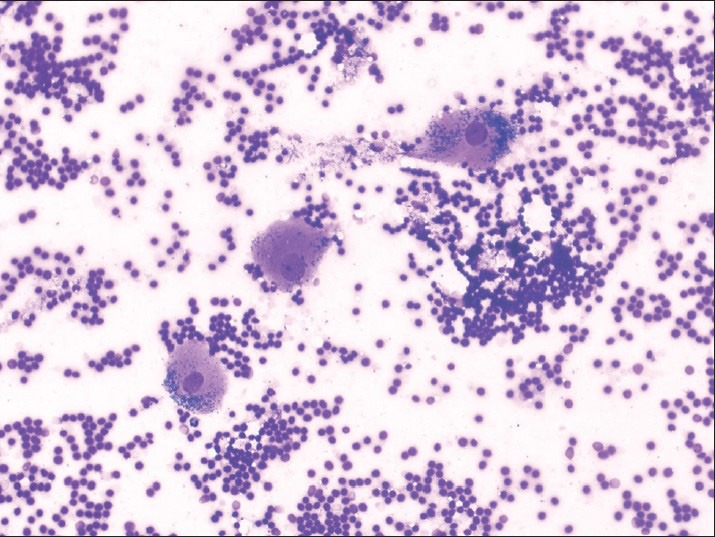

Figure 1.

Fine-needle aspiration smear showing dispersed ganglion cells and a bloody background. Note the distinct darkly stained coarse cytoplasmic neuromelanin substance in these cells (Diff-Quik, ×200)

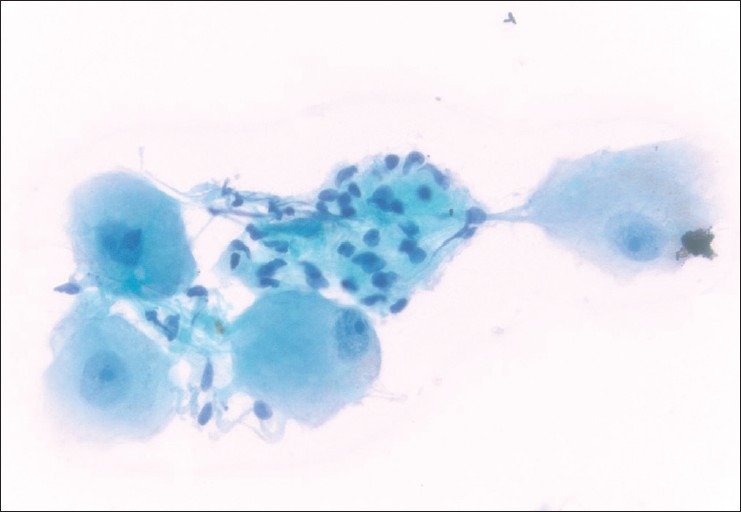

Figure 2.

Cluster of ganglion cells characterized by large epithelioid cells with low N:C ratios, round nuclei, and distinct nucleoli. In addition, there are wavy, comma-shaped nuclei of probable nerve sheath origin in the center of the image (Papanicolaou, ×400)

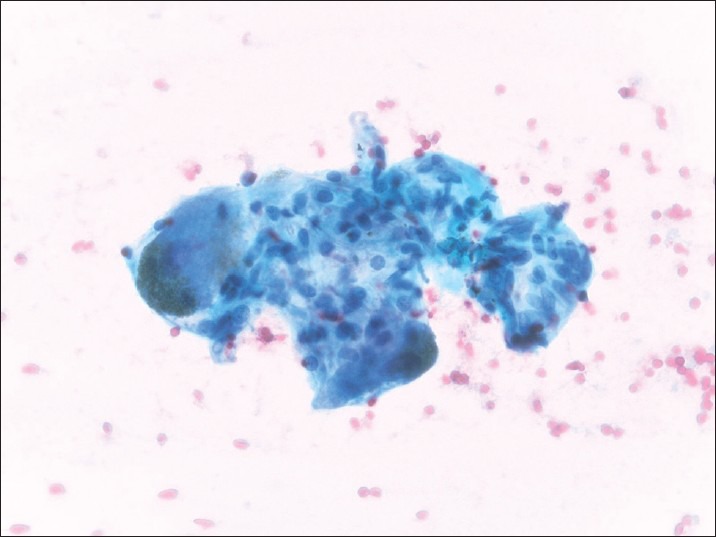

Figure 3.

Ganglion cells are characterized by their brown cytoplasmic neuromelanin pigment granules (Papanicolaou, ×400)

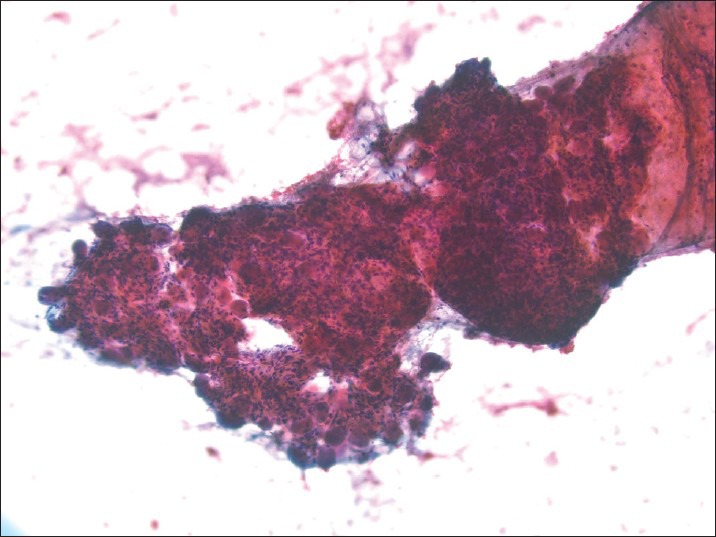

Figure 4.

When intact, clusters of aspirated ganglion cells are located more peripheral to attached central nerve fibers (Papanicolaou, ×100)

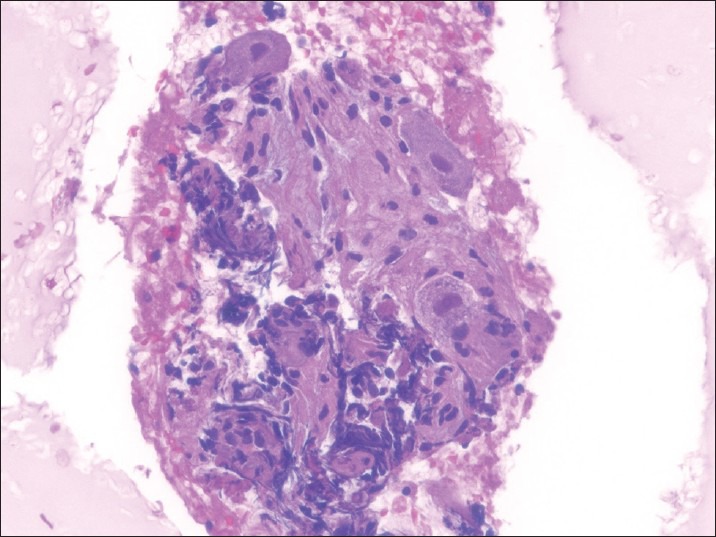

Figure 5.

Cell block section of a celiac ganglion containing large ganglion cells and nerves (H and E, ×400)

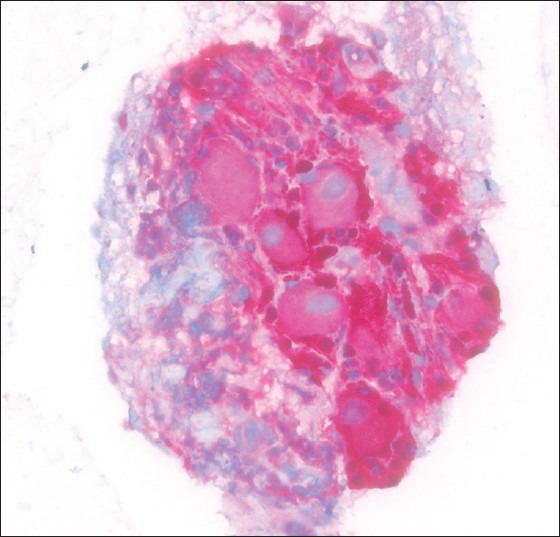

Figure 6.

S100 positive celiac ganglion (immunohistochemistry, ×400)

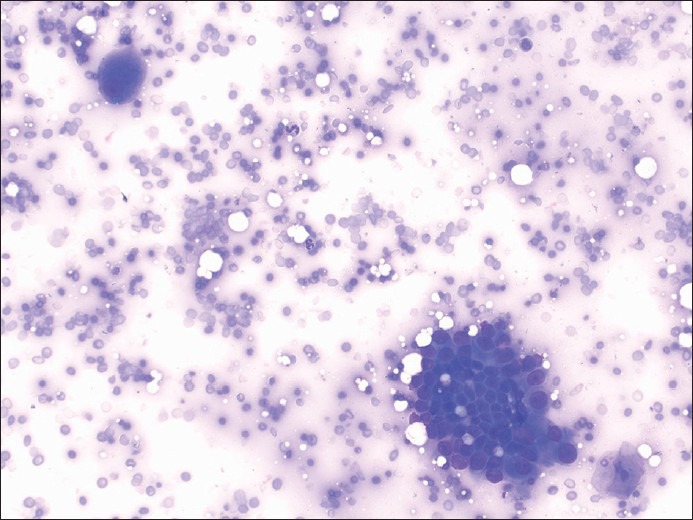

Figure 7.

Fine-needle aspiration showing a ganglion cell in the upper left of the image associated with a group of pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells in the lower right of the image (Diff-Quik, ×200)

DISCUSSION

Review of the pathology literature reveals limited reports of celiac ganglia diagnosed by image-guided FNA.[5,6,7] Ours is the first study that reports the frequency of detecting celiac ganglia by FNA, based on data from our institution. These data indicate that the detection of ganglion cells in image-guided FNA of the celiac region is infrequent (2.5%). It is possible that we may have detected more cases with ganglion cells in our series if all 354 cases were re-screened. Nevertheless, the low incidence in our study is in accordance with data published by radiologists and endoscopists who similarly report only a few cases of celiac ganglia being inadvertently sampled during biopsy of celiac nodes.[4,8,9] Celiac ganglia are more likely to be visualized during EUS-guided procedures than with abdominal imaging. This may explain why all our cases were procured during EUS-guided FNA. On EUS, celiac ganglia are hypoechoic oblong or multilobulated structures with an irregular edge.[4] Echo-poor threads may be seen extending from ganglia, connecting one ganglion to another in a chain. Although it may be difficult to differentiate ganglia from nodes based on sonographic appearances alone, celiac nodes are often located somewhat more anteriorly than celiac ganglia. Celiac nodes also generally do not have irregular margins, and they do not appear in a chain.[9]

The indications for performing an FNA of the celiac ganglia are relatively limited. As demonstrated in our study, these ganglia are most often unintentionally biopsied during the workup of a patient with cancer (pancreatic or esophageal) to exclude celiac lymph node metastases. In prior reports, celiac ganglia have also been sampled to diagnose amyloidosis and viral infection.[10,11] In our patient where a celiac axis mass was targeted, the presence of recurrent pancreatic adenocarcinoma involving the celiac ganglion likely accounted for this patient's abdominal pain. Levy et al. reported similar involvement of abnormal celiac ganglia with pancreatic adenocarcinoma in 2 out of 6 patients.[12]

Albeit a rare finding, given that EUS-guided FNAs are quite common in today's practice, it is important that cytologists are aware of this possibility and can recognize the cytomorphologic features of these ganglia. Our review shows that aspirates of celiac ganglia are likely to be of low cellularity and bloody. If a suspected celiac lymph node was targeted, absence of lymphoid elements should raise the possibility that a ganglion was sampled, which may prompt the performer of the biopsy to see if the targeted lesion was actually sampled. Ganglia consisting of large ganglion cells and accompanying nerves may show varying cellular patterns, including cohesive clusters and/or isolated cells. Benign ganglia should not exhibit cellular atypia. However, the presence of large epithelioid ganglion cells with a prominent nucleolus may at first be alarming. Close inspection should reveal the characteristic low N:C ratio, bland nuclear morphology, and neuromelanin or lipofuscin-like substance (pigment) of these cells.

The morphologic differential diagnosis of celiac ganglia may include several entities. This includes reactive lesions (e.g., histiocytic or hemosiderin-laden granulomatous inflammation, reactive myofibroblastic proliferations such as proliferative myositis) and neoplasms (e.g., melanoma, neurogenic tumors, peripheral neuroblastic tumors, granular cell tumor, rhabdoid tumor, alveolar soft-part sarcoma, germ cell tumor such as seminoma, and Hodgkin lymphoma with a predominance of Reed–Sternberg cells). Melanoma cells may similarly have abundant cytoplasm, melanin pigment that resembles neuromelanin substance and nuclei with prominent nucleoli. However, unlike melanoma ganglion cells lack significant nuclear atypia and are unlikely to display multinucleation. Due to their epithelioid appearance, ganglion cells have to be distinguished from carcinoma including adenocarcinoma, anaplastic or undifferentiated carcinoma. Carcinoma cells will have more nuclear atypia. While ganglion cells may also mimic Reed–Sternberg cells in Hodgkin lymphoma, aspirates in these cases are more likely to be cellular with background reactive lymphoid elements. Finally, it may be difficult to distinguish ganglioneuroma from celiac ganglia based on morphology alone. If the clinical history and imaging findings are concerning for a diagnosis of ganglioneuroma, the differential diagnosis should include this possibility if ganglion cells are present. In ganglioneuroma, the mature ganglion cells are often multinucleated and may contain melanin pigment. The presence of neuromelanin may be less apparent in ganglioneuromas.[13] If ganglion cells are detected, it is important to ensure that there is no accompanying neuroblastomatous component, which would be diagnostic of ganglioneuroblastoma. Ganglioneuroblastoma may also contain melanin pigment.[14] As shown in one case of our study, ganglion cells and nerve fibers can be confirmed with S100 immunopositivity.

In summary, the finding of any benign ganglion material in an FNA sample from the celiac region is infrequent, but may be encountered during an EUS-guided procedure. Recognition of such celiac ganglia in these aspirates is important to avoid a potential diagnostic pitfall. These ganglia may be the cause of a mass-like lesion that was the target of the biopsy, but notifying the proceduralist of this finding during the FNA is important for correlation to make sure that the targeted lesion was not missed with inadvertent sampling of the celiac ganglia.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors contributed to this article and approve of its publication.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

This study received IRB approval.

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double-blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Presented at the American Society of Cytopathology Annual Meeting in Dallas, Texas in November 2014.

Contributor Information

Ehab A. ElGabry, Email: elgabrye@upmc.edu.

Sara E. Monaco, Email: monacose@upmc.edu.

Liron Pantanowitz, Email: pantanowitzl@upmc.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Moore KL, Dalley AF, Agure AM. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2002. Clinically Oriented Anatomy; p. 45. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ward EM, Rorie DK, Nauss LA, Bahn RC. The celiac ganglia in man: Normal anatomic variations. Anesth Analg. 1979;58:461–5. doi: 10.1213/00000539-197911000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mekky MA, Abbas WA. Endoscopic ultrasound in gastroenterology: From diagnosis to therapeutic implications. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:7801–7. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i24.7801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerke H, Silva RG, Jr, Shamoun D, Johnson CJ, Jensen CS. EUS characteristics of celiac ganglia with cytologic and histologic confirmation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:35–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.01.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collins BT, Warrick J. Endoscopic ultrasound fine needle aspiration biopsy of celiac ganglia. Acta Cytol. 2012;56:495–500. doi: 10.1159/000342532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xia D, Gilbert-Lewis KN, Bhutani MS, Nawgiri RS. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration of the celiac ganglion: A diagnostic pitfall. Cytojournal. 2012;9:24. doi: 10.4103/1742-6413.103025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levy GH, Guo M, Zachariah J, Hoda RS. Celiac ganglia diagnosed on endoscopic ultrasound fine-needle aspiration biopsy. Diagn Cytopathol. 2014;42:147–8. doi: 10.1002/dc.22934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ha TI, Kim GH, Kang DH, Song GA, Kim S, Lee JW. Detection of celiac ganglia with radial scanning endoscopic ultrasonography. Korean J Intern Med. 2008;23:5–8. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2008.23.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gleeson FC, Levy MJ, Papachristou GI, Pelaez-Luna M, Rajan E, Clain JE, et al. Frequency of visualization of presumed celiac ganglia by endoscopic ultrasound. Endoscopy. 2007;39:620–4. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ikeda S, Yanagisawa N, Hongo M, Ito N. Vagus nerve and celiac ganglion lesions in generalized amyloidosis. A correlative study of familial amyloid polyneuropathy and AL-amyloidosis. J Neurol Sci. 1987;79:129–39. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(87)90267-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rand KH, Berns KI, Rayfield MA. Recovery of herpes simplex type 1 from the celiac ganglion after renal transplantation. South Med J. 1984;77:403–4. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198403000-00039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levy MJ, Topazian M, Keeney G, Clain JE, Gleeson F, Rajan E, et al. Preoperative diagnosis of extrapancreatic neural invasion in pancreatic cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:1479–82. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jain M, Shubha BS, Sethi S, Banga V, Bagga D. Retroperitoneal ganglioneuroma: Report of a case diagnosed by fine-needle aspiration cytology, with review of the literature. Diagn Cytopathol. 1999;21:194–6. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0339(199909)21:3<194::aid-dc9>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hahn JF, Netsky MG, Butler AB, Sperber EE. Pigmented ganglioneuroblastoma: Relation of melanin and lipofuscin to schwannomas and other tumors of neural crest origin. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1976;35:393–403. doi: 10.1097/00005072-197607000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]