ABSTRACT

Selective IgA deficiency (SIgAD) is the most common type of primary immunoglobulin deficiency. Most individuals with SIgAD are asymptomatic. However, some patients are associated with allergic and autoimmune disease. SIgAD is included in the list of differential diagnoses of eosinophilia. We experienced a patient who initially presented with abdominal pain and eosinophilia. A >1-year follow-up revealed SIgAD, and we had difficulty differentiating it from Churg-Strauss syndrome (CSS) or hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES). A 66-year-old Japanese male presented with a history of recurrent abdominal pain. A diagnostic work-up revealed eosinophilia, eosinophilic gastritis, eosinophilic pneumonia, and SIgAD over 1 year of clinical observation. He also suffered from asthma and sinusitis. Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody was negative and vasculitis was not detected in the obtained tissue specimens of stomach, lung, nose and skin. The patient showed no evidence of drug ingestion, parasitic infections, or malignant neoplasms. Although we cannot rule out prevasculitic CSS and idiopathic HES, the whole clinical picture in this patient can be explained most consistently by SIgAD.

Key Words: Selective IgA deficiency, Churg-Strauss syndrome, Hypereosinophilic syndrome, Eosinophilic gastroenteritis, Eosinophilic pneumonia

INTRODUCTION

Selective IgA deficiency (SIgAD) is the most common type of primary immunoglobulin deficiency.1-7) It is defined as a decreased serum level of IgA in the presence of normal levels of other immunoglobulin isotypes,1-6) where secretory IgA levels are often reduced as well.2,5) The prevalence of SIgAD varies depending on ethnic groups, and ranges from 1:155 in Spain to 1:18,550 in Japan.1-4,6) Most individuals with SIgAD are asymptomatic and identified coincidentally.1-6) However, some patients present with allergic diseases such as asthma and rhinitis, drug allergy, and a number of autoimmune diseases such as thyroid disease and systemic lupus erythematosus.1-3,6)

Although the function of serum IgA in the systemic immune response has not been clearly understood, secretory IgA, in the dimeric form, has been known as a prominent immunoglobulin in luminal secretions of the respiratory and gastrointestinal tract, and as an important component of mucosal immunity.1-4,7)

We report a 66-year-old Japanese male with a history of asthma who presented with recurrent abdominal pain. A diagnostic work-up revealed eosinophilia, eosinophilic gastritis, eosinophilic pneumonia, and SIgAD over a year of clinical observation. We had great difficulty differentiating Churg-Strauss syndrome (CSS), hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES), and SIgAD, and currently we are considering that the whole clinical picture can be explained by SIgAD.

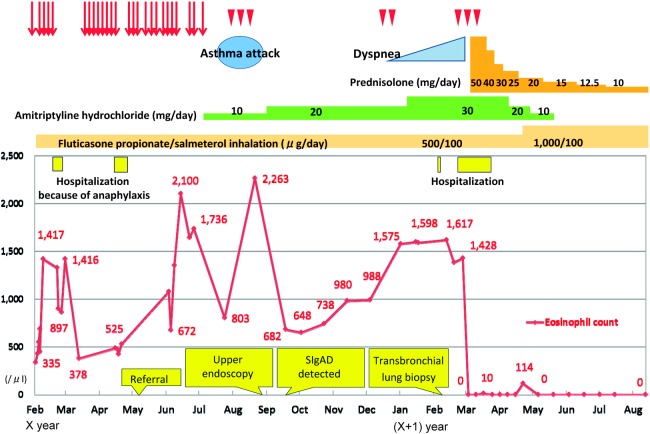

CASE PRESENTATION (Fig. 1)

Fig. 1.

Clinical course. The patient had repeatedly visited the emergency room at the previous institution because of severe recurrent abdominal pain of an unknown cause (red arrows). He also had sporadic abdominal pain repeatedly, without emergency visits (arrow heads).

A 66-year-old Japanese male was referred to our institution because of severe recurrent abdominal pain of an unknown cause. He had repeatedly visited the emergency room at the previous institution and was evaluated by a gastroenterologist, but no abnormalities were detected. His abdominal pain was characterized as epigastric pain radiating to the right upper quadrant that usually occurred at night and lasted 3 to 6 hours. He was symptom-free between the attacks. The pain sometimes, but not always, required pain medication. Anticholinergic drugs were occasionally effective for the pain and pentazocine was the most effective. During the pain attacks, he frequently had borborygmi and nasal drip, but had no nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, weight loss, appetite loss, headache, cough, or fever.

The patient had a history of asthma since the age of 57 and had been using inhaled fluticasone propionate and salmeterol. In terms of significant medical history, he had developed anaphylactic shock on two occasions: once when he took loxoprofen sodium hydrate and lansoprazole concurrently, and the other when he was given ketoprofen through intravenous infusion. He also once developed a rash over his entire body after taking itraconazole per os.

At the time of referral, his physical examination was unremarkable. Laboratory tests revealed mild eosinophilia (white blood cell count, 8,400/μl with an 8% eosinophil count, 672/μl) without any other significant findings; normal results were obtained on analysis of renal function including urine analysis, liver function, IgE, C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibody, thyroid-stimulating hormone, adrenocorticotropic hormone, and cortisol. Enhanced computed tomography (CT) from the chest to the abdomen detected a right kidney stone that did not obstruct the urinary tract and could not account for the abdominal pain. CT scan also detected a discoid atelectasis in the upper lobe of the right lung, but it was not considered to be a significant finding by a radiologist. His abdominal pain was dramatically improved with 10 mg of amitriptyline daily at bedtime.

Ten weeks later, his abdominal pain relapsed with asthma. At that time, laboratory data revealed moderate eosinophilia (white blood cell count, 7,300/μl with a 31% eosinophil count, 2,263/μl). Upper endoscopy revealed gastroesophageal reflux disease and chronic gastritis. A random stomach biopsy revealed eosinophil infiltration and indicated eosinophilic gastritis without vasculitis. After this attack of abdominal pain and asthma, the patient’s condition was stabilized for about the next 3 months with an increased dose of amitriptyline to 20 mg daily and symptomatic treatment for asthma. Because the patient’s condition was stabilized and his pain was relieved, we decided not to use oral corticosteroid but instead sought to ascertain the cause of eosinophilia.

Additional examinations revealed a low serum IgA level (2 mg/dl; normal, 110–410 mg/dl) and normal levels of serum IgG, IgG subclass, IgE, and IgM. No other abnormalities were detected with respect to PR3-antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA), MPO-ANCA, beta-D-glucan, quantiferone®, human immunodeficiency virus antibody, interleukin-5, vitamin B12, and the Fip1-like-1/platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (FIP1L1-PDGFRA) gene. Stool specimens were negative for ova and parasites, and serum antibody screening for parasitic infections was negative.

At this point, our differential diagnosis of hypereosinophilia had been narrowed down to CSS, idiopathic HES, and SIgAD.

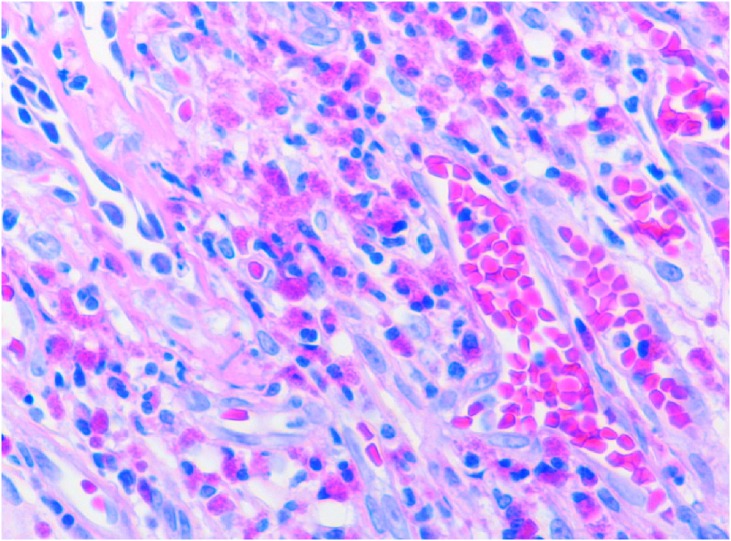

Six months after referral, a follow-up CT from chest to paranasal sinus was obtained to rule out CSS. It revealed consolidation of the right middle lobe and bilateral maxillary sinusitis without apparent clinical symptoms. However, 2 months later, he developed gradual dyspnea. A transbronchial lung biopsy via bronchoscopy from the right middle lobe revealed eosinophilic infiltration of the lung tissue and indicated eosinophilic pneumonia, although vasculitis was not detected (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Histopathology specimen from the lung showed inflammation with eosinophilic infiltration, without vasculitis. Hematoxylin and eosin stain; magnification: ×400.

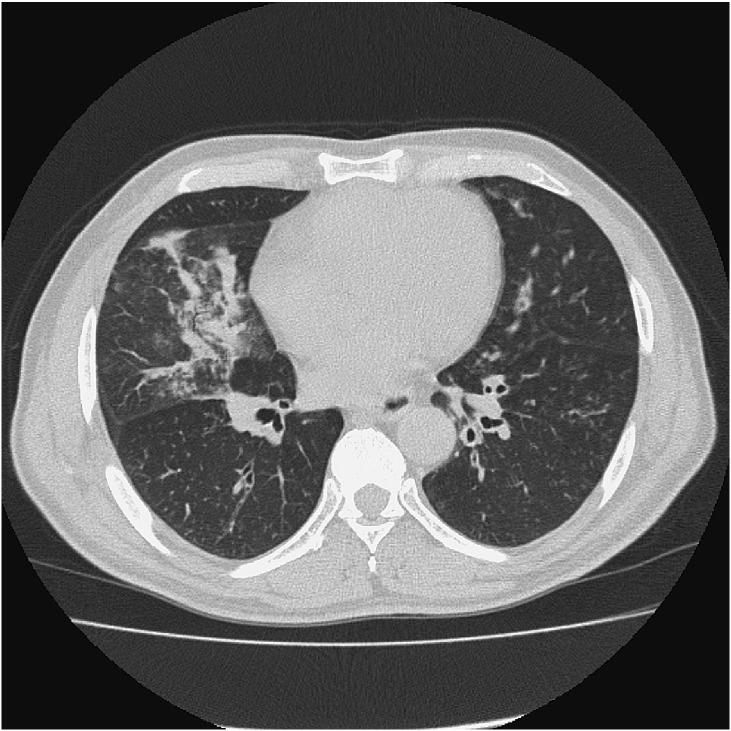

Three weeks after bronchoscopy, he visited our emergency department because of worsening cough and dyspnea at rest and was admitted to the hospital. Repeated CT of the chest revealed worsening consolidation of the right middle lobe (Fig. 3). Fluorine-18 fludeoxyglucose positron emission tomography ([18F]FDG-PET) with CT revealed [18F]FDG uptake in the area of consolidation of the right middle lobe, but no other specific accumulation. Nasal biopsy showed eosinophilic infiltration, but no evidence of vasculitis. Skin biopsy, from the erythematous legion then observed on the chest, revealed lymphocytic infiltration with no evidence of vasculitis. During this hospitalization, paroxysmal nocturnal abdominal pain attacks occurred a number of times and were relieved by intramuscular butylscopolamine bromide. Although we had not reached a definitive clinical diagnosis to explain the whole clinical picture, we decided to start oral prednisolone 50 mg daily on the 6th day of admission for eosinophilic gastritis and pneumonia because of his deteriorating condition. His abdominal pain disappeared in 2 days and lung consolidation also disappeared in 2 weeks. Twenty days after starting prednisolone, he was discharged. Since discharge from the hospital, he had been symptom-free for 5 months and his prednisolone had been tapered down to 10 mg daily.

Fig. 3.

Chest computed tomography on admission revealed consolidation of the right middle lobe and bronchial wall thickening of the left lower lobe (9 months post-referral).

DISCUSSION

In this case, the patient had recurrent abdominal pain with eosinophilia, and a diagnostic work-up revealed eosinophilic gastritis, eosinophilic pneumonia, and SIgAD. He also suffered from asthma and sinusitis. No biopsy specimen from 4 different sites, stomach, lung, nose and skin, revealed vasculitides. No evidence of causes of eosinophilia, such as drugs, parasitic infections, or malignant neoplasms, was detected. Although it is impossible to rule out the possibilities of prevasculitic CSS or idiopathic HES, SIgAD may be able to explain all the clinical presentations of this patient. We would like to briefly review the current understanding of these disorders, contrasting them with the clinical presentation of this patient.

SIgAD

Eighty-five to 90% of individuals with SIgAD are asymptomatic.1) However, some patients with SIgAD develop recurrent sinopulmonary infections, gastrointestinal infections and disorders, autoimmune conditions, and malignancies.1-7) Allergic disorders commonly appear in patients with SIgAD as well. In a recent report, allergic manifestations including asthma, atopic dermatitis, allergic rhinitis/conjunctivitis, urticaria, drug allergy, and food allergy were noted in 84% of patients with SIgAD.8) Our patient had a history of asthma, two episodes of drug-induced anaphylactic shock, and an episode of drug-induced skin eruption.

Furthermore, SIgAD is known to cause secondary eosinophilia9,10) and is associated with eosinophilic gastroenteritis.11) This patient’s first presentation was eosinophilic gastritis. His second presentation was eosinophilic pneumonia. Although no apparent relationship between SIgAD and eosinophilic pneumonia has been reported, an association between SIgAD and respiratory hypersensitivities has been suggested.12) Pulmonary pathology of this patient could also be explained by SIgAD.

CSS

CSS is a rare small-vessel vasculitis that is associated with asthma, granulomatous inflammation, peripheral/tissue eosinophilia and a positive ANCA status (in approximately 40% of patients).13-16) Although this disease’s hallmarks are now well-known, its pathophysiological mechanisms remain to be fully understood. CSS usually progresses through three phases that frequently overlap. It begins with a prodromal phase that has asthmatic and allergic manifestations. The second phase presents with peripheral eosinophilia and may be associated with organ involvement. Characteristic eosinophilic infiltration occurs in the lungs or gastrointestinal tract. Finally, about 3–4 years (range 2 months–30 years) after the onset of asthma, a systemic phase with necrotizing vasculitis develops.13-18) In this patient, although the absence of ANCA and the lack of vasculitis kept him from meeting the criteria,14) the possibility of prevasculitic CSS remained.

HES

HES is a rare disorder characterized by marked hypereosinophilia that is directly responsible for organ damage or dysfunction. Different pathogenic mechanisms have been discovered in patient subgroups leading to the characterization of myeloproliferative and lymphocytic disease variants. In the updated terminology, the diagnosis of idiopathic HES is now restricted to patients with HES of undetermined etiology.19-21)

Some studies have suggested that patients with a tentative diagnosis of CSS who are ANCA-negative and lack vasculitis may have a subset of HES.18) Molecular analyses to detect FIP1L1-PDGFRA gene fusion therefore probably should be performed for every patient suspected of having CSS, at least for those who are ANCA-negative and/or without histologically proven vasculitis, to detect myeloneoplasms.16,22) This gene survey was negative in this patient. Patients with HES in the setting of a clonal bone marrow disease do not typically respond to glucocorticoid therapy, in contrast to patients with secondary or idiopathic HES.19,20) In this patient, although there was no supportive evidence of myeloneoplasms, we cannot rule out the possibility of idiopathic HES in differential diagnosis.

Possible pathophysiology in this patient

Traditionally, the gut and the lung are considered to be part of a common mucosal system.23) An immunologic link between the gastrointestinal tract and respiratory tract is postulated via several common mucosal immune hypotheses.23-25) Also, secretory IgA plays an important role in both sites.1,4,7) When protective functions of secretory IgA are deficient, a variety of complex and incompletely understood pathophysiologic events could occur, resulting in pathophysiology of a variety of systemic organs including gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts.1-5,7,23-25) Although we cannot rule out prevasculitic CSS and idiopathic HES, the whole clinical picture of this patient can be explained by SIgAD.

CONCLUSION

We herein reported a patient with eosinophilia, eosinophilic gastritis, eosinophilic pneumonia and SIgAD, without ANCA or pathologic findings of vasculitis. Although ruling out prevasculitic CSS or idiopathic HES is impossible, the whole clinical picture of this patient can be explained most consistently by SIgAD.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We sincerely thank Dr. Kei Miyazaki and Dr. Kei Mukohara for their invaluable suggestions.

REFERENCES

- 1).Yel L. Selective IgA deficiency. J Clin Immunol, 2010; 30: 10–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2).Latiff AH, Kerr MA. The clinical significance of immunoglobulin A deficiency. Ann Clin Biochem, 2007; 44: 131–139. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3).Cunningham-Rundles C. Physiology of IgA and IgA deficiency. J Clin Immunol, 2001; 21: 303–309. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4).Driessen G, van der Burg M. Educational paper: primary antibody deficiencies. Eur J Pediatr, 2011; 170: 693–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5).Agarwal S, Mayer L. Pathogenesis and treatment of gastrointestinal disease in antibody deficiency syndromes. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2009; 124: 658–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6).Wang N, Shen N, Vyse TJ, Anand V, Gunnarson I, Sturfelt G, Rantapää-Dahlqvist S, Elvin K, Truedsson L, Andersson BA, Dahle C, Ortqvist E, Gregersen PK, Behrens TW, Hammarström L. Selective IgA deficiency in autoimmune diseases. Mol Med (Cambridge, Mass.), 2011; 17: 1383–1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7).Woof JM, Kerr MA. The function of immunoglobulin A in immunity. J Pathol, 2006; 208: 270–282. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8).Aghamohammadi A, Cheraghi T, Gharagozlou M, Movahedi M, Rezaei N, Yeganeh M, Parvaneh N, Abolhassani H, Pourpak Z, Moin M. IgA deficiency: correlation between clinical and immunological phenotypes. J Clin Immunol, 2009; 29: 130–136. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9).Messa E, Cilloni D, Saglio G. A young man with persistent eosinophilia. Intern Emerg Med, 2007; 2: 107–112. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10).Fauci AS, Harley JB, Roberts WC, Ferrans VJ, Gralnick HR, Bjornson BH. NIH conference. The idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome. Clinical, pathophysiologic, and therapeutic considerations. Ann Intern Med, 1982; 97: 78–92. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11).Hogan SP, Rothenberg ME. Eosinophil function in eosinophil-associated gastrointestinal disorders. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep, 2006; 6: 65–71. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12).Pilette C, Durham SR, Vaerman JP, Sibille Y. Mucosal immunity in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a role for immunoglobulin A? Proc Am Thorac Soc, 2004; 1: 125–135. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13).Abril A. Churg-Strauss syndrome: an update. Curr Rheumatol Rep, 2011; 13: 489–495. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14).Holle JU, Moosig F, Gross WL. Diagnostic and therapeutic management of Churg-Strauss syndrome. Expert Rev Clin Immunol, 2009; 5: 813–823. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15).Sinico RA, Bottero P. Churg-Strauss angiitis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol, 2009; 23: 355–366. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16).Pagnoux C, Guillevin L. Churg-Strauss syndrome: evidence for disease subtypes? Curr Opin Rheumatol, 2010; 22: 21–28. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17).Lanham JG, Elkon KB, Pusey CD, Hughes GR. Systemic vasculitis with asthma and eosinophilia: a clinical approach to the Churg-Strauss syndrome. Medicine (Baltimore), 1984; 63: 65–81. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18).Kallenberg CG. Churg-Strauss syndrome: just one disease entity? Arthritis Rheum, 2005; 52: 2589–2593. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19).Cogan E, Roufosse F. Clinical management of the hypereosinophilic syndromes. Expert Rev Hematol, 2012; 5: 275–289. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20).Valent P, Gleich GJ, Reiter A, Roufosse F, Weller PF, Hellmann A, Metzgeroth G, Leiferman KM, Arock M, Sotlar K, Butterfield JH, Cerny-Reiterer S, Mayerhofer M, Vandenberghe P, Haferlach T, Bochner BS, Gotlib J, Horny HP, Simon HU, Klion AD. Pathogenesis and classification of eosinophil disorders: a review of recent developments in the field. Expert Rev Hematol, 2012; 5: 157–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21).Valent P, Klion AD, Horny HP, Roufosse F, Gotlib J, Weller PF, Hellmann A, Metzgeroth G, Leiferman KM, Arock M, Butterfield JH, Sperr WR, Sotlar K, Vandenberghe P, Haferlach T, Simon HU, Reiter A, Gleich GJ. Contemporary consensus proposal on criteria and classification of eosinophilic disorders and related syndromes. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2012; 130: 607–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22).Hellmich B, Holl-Ulrich K, Merz H, Gross WL. Hypereosinophilic syndrome and Churg-Strauss syndrome: is it clinically relevant to differentiate these syndromes? Internist (Berl), 2008; 49: 286–296. [Article in German] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23).Braunstahl GJ. The unified immune system: respiratory tract-nasobronchial interaction mechanisms in allergic airway disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2005; 115: 142–148. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24).Powell N, Walker MM, Talley NJ. Gastrointestinal eosinophils in health, disease and functional disorders. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2010; 7: 146–156. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25).Kudsk KA. Current aspects of mucosal immunology and its influence by nutrition. Am J Surg, 2002; 183: 390–398. [DOI] [PubMed]