ABSTRACT

We present an extreme rare case of traumatic partial avascular necrosis of the lunate after palmar perilunate dislocation with lunate fracture. A 32-year-old female was injured by motorcycle accident with palmar perilunate fracture dislocation and lunate fracture. Scapholunate and lunotriquetrum dislocations were reduced and fixed temporarily. The torn dorsal ligament was repaired. Considering close observation with both arthroscopy and fluoroscopy, we decided not to conduct open reduction and internal fixation for the lunate. Partial avascular necrosis of the lunate appeared gradually in follow-up.

Key Words: lunate fracture, necrosis, perilunate dislocation

INTRODUCTION

Perilunate fracture dislocation is a rare injury often associated with high-energy trauma. Most perilunate fracture dislocations are dorsal, with palmar dislocations accounting for only 3% of cases1). Lunate fracture is also a rare injury. It is seldom an isolated injury and is often associated with other carpal fractures and ligament injuries2,3).

In this paper, we report a patient with an extremely rare complex wrist injury consisting of translunate palmar perilunate fracture dislocation that developed traumatic partial avascular necrosis of the lunate.

CASE REPORT

A 32-year-old female was transported to the emergency unit with a complaint of severe left wrist pain after falling onto her left wrist while driving a motorcycle. The initial examination revealed swelling and tenderness around the left wrist and weakness of grip. The patient did not show any evidence of nerve injury or vascular insufficiency. X-rays demonstrated a palmar perilunate dislocation and radial styloid fracture (Fig. 1). Immediate closed reduction was performed. Post-reduction x-rays showed an adequate reduction, but an increased scapholunate interval of approximately 3 mm was noticed. Computed tomography (CT) demonstrated associated injuries including a coronal fracture of the lunate (Fig. 2), a trapezium fracture, and a triquetrum fracture.

Fig. 1.

Injury posterioanterior (PA) (a) and lateral (b) radiographs of the left wrist demonstrating the palmar perilunate dislocation, the radial styloid fracture and an increased scapholunate interval.

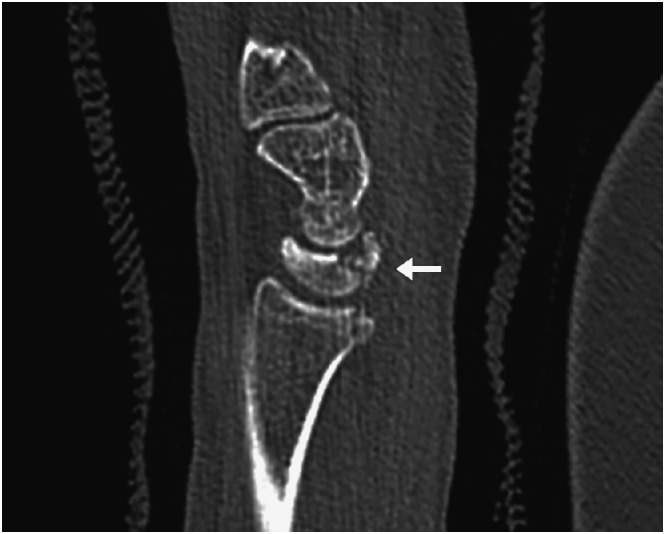

Fig. 2.

Sagittal computed tomography scan demonstrating volar pole fracture of the lunate (arrow).

The patient underwent surgery four days after injury. The arthroscopy revealed a lunatotriquetral interosseous ligament (LTIL) tear, while the triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC) was intact. The lunate fracture was located in the volar 20% of the articular surface. The dorsal scapholunate interosseus ligament (dSLIL) was avulsed from the radial edge of the lunate. The radial styloid was reduced and fixed percutaneously with two 1.5 mm K-wires. Both scapholunate and lunotriquetrum dislocations were reduced and fixed temporarily with two 1.1 mm K-wires, respectively. The volar fragment could not be reduced arthroscopically into the original alignment, and reduction of this fragment required a volar approach. Then the torn dSLIL was repaired with a micro Mitek anchor (Depuy Mitek, Raynham, MA) into the lunate. After that, we confirmed the adequate restoration of the carpal alignment with fluorosocpy. We decided not to conduct open reduction and internal fixation for the palmar fragment of the lunate. Postoperative x-rays showed normal carpal alignment with the carpal height ratio (CHR) being 0.51, radiolunate angle (RL angle) 4°, scapholunate angle (SL angle) 43°, and capitolunate angle (CL angle) –10° (Fig. 3). The wrist was put in a short arm cast for three weeks and then active range of motion exercise was initiated. At six weeks after surgery, all the K-wires were removed and the patient was encouraged to begin gentle passive range of motion exercises.

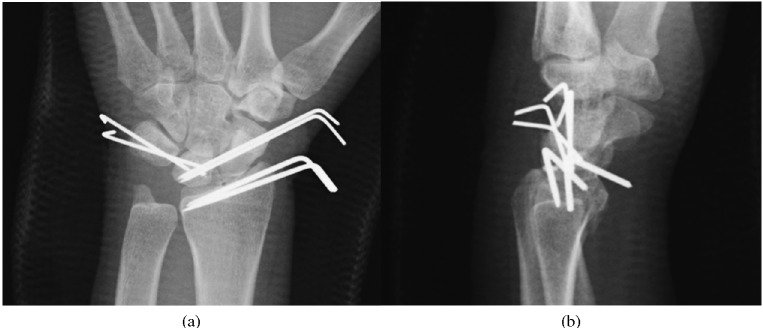

Fig. 3.

Postoperative PA (a) and lateral (b) radiographs demonstrating fixation of scapholunate interval, lunotriquetral interval and radial styloid.

The patient had regained 40° of flexion and 20° of extension in her left wrist at the two-month follow-up. The grip strength was 28 kg on the right and 6.1 kg on the left. Range of motion (ROM) of the operated wrist increased to 40° of flexion and 50° of extension at the six-month follow-up. Grip strength also increased to 15.7 kg on the left. The patient complained of occasional mild wrist pain only after heavy use at the one-year follow-up. On physical examination, grip strength had increased to 18.6 kg, while the wrist motion remained restricted with volar flexion of 45° and dorsal flexion of 50°.

At two months post-surgery, X-rays showed no remarkable changes in the carpus. However, X-rays at six months after surgery demonstrated a relative increase in radiodensity and collapse in the volar fragment of the lunate. The volar fragment showed very low signal intensity on T1 weighted images and relative low signal intensity on T2 weighted images, indicating hypovascularity of the area, while that of the dorsal lunate fragment remained as high as other surrounding bones (Figs. 4). X-rays at the one-year follow-up revealed apparent progression of both sclerosis and collapse of the volar fragment, suggesting the occurrence of delayed post-traumatic osteonecrosis, although carpal alignment remained normal, with CHR of 0.41, RL angle 42°, SL angle 28°, and CL angle 39° (Figs 5). Therefore, we recommended an MRI for evaluation of circulatory status. However, the patient did not have any difficulties in daily life activities and rejected the proposal. In fact, on the Hand20, a validated patient-rated upper extremity disability assessment instrument, the score was 5.5 at one year post-surgery. The patient seemed to report fairly good hand function despite radiological appearance when considering that the reported Hand20 score among unimpaired persons aged 30–39 years is 1.2 ± 5.2 (the highest score of 100 represents the worst subjective function, and the lowest score of 0 represents the best function)4).

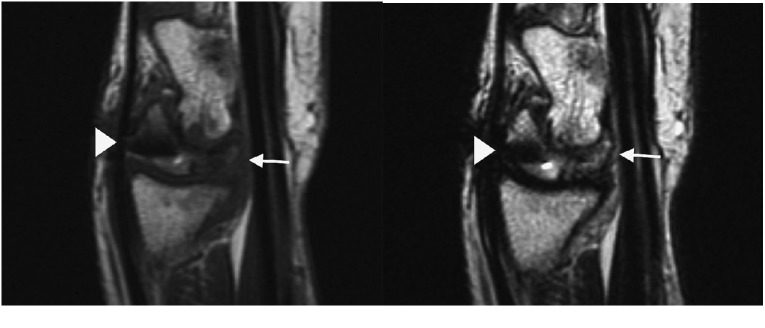

Fig. 4.

Magnetic resonance imaging demonstrating very low signal intensity on T1 weighted image (a) and relative low signal intensity on T2 weighted image (b) at the volar fragment. Arrow, volar fragment; arrowhead, micro Mitek anchor.

Fig. 5.

One-year postoperative PA (a) and lateral (b) radiographs demonstrating a relative increase in radiodensity and collapse of the volar fragment (arrow).

DISCUSSION

Perilunate dislocation has historically been associated with carpal bone fractures, except for the lunate. According to Mayfield et al. 2) who proposed the so-called progressive perilunate pattern concept, the energy dissipates around the lunate, not through it, except in the case of progressive perilunate instability IV, i.e. lunate dislocation. Johnson3) classified this injury based on the injury propagation pattern into two types, i.e., lesser arc and greater arc injuries. The lesser arc injury is a pure ligament injury and the ligaments immediately surrounding the lunate are involved. However, the injury propagates through the scaphoid, capitate, and/or triquetrum in the greater arc injury. Pure lesser arc or greater arc lesions are rare, and most cases are combined ligament ruptures, bone avulsions and fractures in a variety of forms. Conway et al. 5) reported 3 cases of palmar perilunate injury with the lunate fracture in 1989, since then, only 8 cases were reported5-9).

Teisen and Hjarbaek10) reviewed 3256 carpal bone fractures over a period of 31 years and found 17 fresh lunate fractures, accounting for only 0.5% of all carpal bone fractures, but none developed osteonecrosis of the lunate. Gelberman et al. 11) conducted a cadaveric study and concluded that one or two major nutrient vessels enter through the volar and/or dorsal poles. Therefore the palmar and dorsal carpal ligament attachments are important with respect to the vascular supply to the lunate. The varieties of branching and anastomosing intraosseous network could be divided into three basic patterns, which he named Y, X and I patterns. The Y pattern is either dorsal or volar with the two limbs entering the opposite pole. The X pattern is two dorsal and two volar vessels anastomosing in the center of the lunate. The I pattern is a single dorsal and volar vessel anastomosing in a straight line across the lunate. Lee12) described three intraosseus vascular patterns: Group A, a single palmar or dorsal vessel crossing the bone obliquely (26%); Group B, palmar and dorsal vessels which do not anastomose (7.5%); Group C, palmar and dorsal vessels which anastomose with each other (66.5%). Therefore, in the Group A lunates, vascular necrosis of the volar or the dorsal fragment can occur after coronal fracture, at least theoretically. In fact, Freeland and Ahmad13) reported two cases of displaced shear fracture of the lunate which were associated with distal radius fractures, with one patient having transient signs of vascular compromise after open reduction and mini-screw fixation.

According to the previous reports5), osteosynthesis of the lunate prevented necrosis at least 12 months after operation. The femoral neck fracture also causes avascular necrosis of the femoral head, however, early reduction and osteosynthesis can avoid femoral head necrosis14). We repaired only the dorsal ligament of the lunate, however, these instances indicate that secure osteosynthesis would have avoided osteonecrosis in this case. The patient regained fairly good function in spite of radiological signs of delayed traumatic osteonecrosis in the volar fragment at just one year follow-up. The osteoarthritis may occur in the future and we must need further follow-up.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors did not receive and will not receive any benefits or funding from any commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article

REFERENCES

- 1).Herzberg G, Comtet JJ, Linscheid RL, Amadio PC, Cooney WP. Perilunate dislocations and fracture-dislocations -a multicenter study. J Hand Surg Am. 1993 Sep; 18(5): 768–79 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2).Mayfield JK, Johnson RP, Kilcoyne RK. Carpal dislocations: pathomechanics and progressive perilunar instability. J Hand Surg Am. 1980 May; 5(3): 226–41. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3).Johnson RP. The acutely injured wrist and its residuals. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1980 Jun; 149: 33–44. [PubMed]

- 4).Suzuki M, Kurimoto S, Shinohara T, Tatebe M, Imaeda T, Hirata H. Development and validation of an illustrated questionnaire to evaluate disabilities of the upper limb. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010 Jul; 92(7): 963–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5).Conway WF, Gilula LA, Manske PR, Kriegshauser LA, Rholl KS, Resnik C. Translunate, palmar perilunate fracture-subluxation of the wrist. J Hand Surg Am. 1989 Jul; 14(4): 635–9 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6).Masmejean EH, Romano SJ, Saffar PH. Palmar perilunate fracture-disclocation of the carpus. J Hand Surg Br. 1998 Apr; 23(2): 264–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7).Bain GI, McLean JM, Turner PC, Sood A, Pourgiezis N. Translunate fracture with associated perilunate injury: 3 case reports with introduction of the translunate arc concept. J Hand Surg Am. 2008 Dec; 33(10): 1770–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8).Briseño MR, Yao J. Lunate fractures in the face of a perilunate injury: an uncommon and easily missed injury pattern. J Hand Surg Am. 2012 Jan; 37(1): 63–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9).Enoki NR, Sheppard JE, Taljanovic MS. Transstyloid, translunate fracture-dislocation of the wrist: case report. J Hand Surg Am. 2008 Sep; 33(7): 1131–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10).Teisen H, Hjarbaek J. Classification of fresh fractures of the lunate. J Hand Surg Br. 1988 Nov; 13(4): 458–62. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11).Gelberman RH, Bauman TD, Menon J, Akeson WH. The vascularity of the lunate bone and Kienböck’s disease. J Hand Surg Am. 1980 May; 5(3): 272–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12).Lee M. The intraosseous arterial pattern of the carpal lunate bone and its relation to avascular necrosis. Acta Orthop Scand. 1963; 33: 43–55. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13).Freeland AE, Ahmad N. Oblique shear fractures of the lunate. Orthopedics. 2003 Aug; 26(8): 805–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14).Manninger J, Kazar G, Fekete F, Nagy E, Zolczer L, Frenyo S. Avoidance of avascular necrosis of the femoral head, following fracture of the femoral neck, by early reduction and internal fixation. Injury. 1985; 16(7): 437–48 [DOI] [PubMed]