Key messages

Local community members' interpretation of patient-centred medical home components leads to community-relevant perspectives and messages for both patients and clinical providers.

For patients, the formal components of the patient-centred medical home are conducted and maintained in service to the patient–provider relationship.

Related LJPC papers

Chana N and Ahluwalia S (2014) Evaluating the care of patients with long-term conditions. London Journal of Primary Care 6:131–5.

Morris D (2014) Introducing Volume 6 of London Journal of Primary Care: community-oriented integrated care. London Journal of Primary Care 6:1–2.

Why this matters to us

The High Plains Research Network (HPRN) aspires to broad community, patient and provider engagement in all research projects. The Community Advisory Council (CAC) includes local farmers, ranchers, schoolteachers, business owners and students, and guides all the research conducted in the HPRN. After hearing about the patient-centred medical home, the CAC raised concerns about how the PCMH was truly patient centred. The CAC wanted to learn more about the medical home and help translate the formal patient-centred medical home components into language and constructs more relevant to patients.

Keywords: community-based participatory research, patient-centred medical home, rural

Abstract

Background The patient-centred medical home (PCMH) is a healthcare delivery model that aims to make health care more effective and affordable and to curb the rise in episodic care resulting from increasing costs and sub-specialisation of health care. Although the PCMH model has been implemented in many different healthcare settings, little is known about the PCMH in rural or underserved settings. Further, less is known about patients' understanding of the PCMH and its effect on their care.

Aims The goal of this project was to ascertain the patient perspective of the PCMH and develop meaningful language around the PCMH to help inform and promote patients' participation with the PCMH.

Method The High Plains Research Network Community Advisory Council (CAC) is comprised of a diverse group of individuals from rural eastern Colorado. The CAC and its academic partners started this project by receiving a comprehensive education on the PCMH. Using a community-based participatory research approach, the CAC translated technical medical jargon on the PCMH into a core message that the ‘Medical Home is Relationship’.

Results The PCMH should focus on the relationship of the patient with their personal physician. Medical home activities should be used to support and strengthen this relationship.

Conclusion The findings serve as a reminder of the crucial elements of the PCMH that make it truly patient centred and the importance of engaging local patients in developing and implementing the medical home.

Introduction

The patient-centred medical home (PCMH) is a model to efficiently organise and deliver primary care in a community context.1–3 The idea of a ‘medical home’ has existed for over four decades and continues to undergo significant changes in order to meet the needs of healthcare providers, payers and patients. Many types of primary care practices are making efforts to implement the PCMH, with some actively pursuing PCMH certification. Significant research to assess provider and clinical outcomes in PCMH practices has been conducted with mostly positive results.4–9

Ironically, even though this model has been named ‘patient centred’, there has been less research to assess the patient's perspective on the PCMH.10,11 Upon hearing a presentation about PCMH, the High Plains Research Network (HPRN) Community Advisory Council (CAC) voiced concern that many of the PCMH elements did not seem patient centred, but rather focused on the practice and provider. The CAC requested to learn more about the PCMH and consider methods for assuring that PCMH work done in their rural practices was locally relevant, community engaged and truly patient centred. The purpose of this project was twofold: (1) to gain an understanding of how the idea of a PCMH is perceived and accepted by community members and patients, and (2) to use this community knowledge and expertise to translate the complicated PCMH concepts into accessible and meaningful language for the local community.

Methods

This project used a community-based participatory research approach and was conducted by the HPRN and its CAC. The HPRN is a community- and practice-based research network based out of the University of Colorado Denver Anschutz Medical Campus. The HPRN works with the primary care providers, hospitals, behavioural health centres, public health organisations and communities in the 16 counties in rural and frontier Eastern Colorado.12 The CAC was developed in 2003 and consists of a diverse group of eastern Colorado residents from retirees to college students, store owners, ranchers and schoolteachers.13 Since its creation, the CAC has played an invaluable role in the successes of the HPRN.

For this project, HPRN staff and the CAC conducted a boot-camp translation (BCT) on the PCMH (Box 1). The BCT was designed to translate evidence-based medical research into locally relevant, patient-friendly concepts and language. A detailed description of the BCT was published by Norman et al.14 The principles and benefits of this community-engagement strategy are similar to several experienced in community development efforts, as described by Fisher.15

Box 1. What is Boot Camp Translation?

Boot camp translation (BCT) is a process by which medical information and clinical guidelines are translated into concepts, messages and materials that are understandable, meaningful and engaging to community members. The ultimate goal is to improve the health of individuals and communities.

BCT utilises the skills and expertise of academic researchers and community members. Community-academic partnerships work together to address two main questions about a selected health topic:

What is the message to our community? (or what health-related information does our community need to hear?)

How do we effectively share that information with our community?

BCT uses in-person meetings and short conference calls and can last 6–18 months, depending on the scope of the project and complexity of topic.

The information and data for this study were obtained using the BCT process. Table 1 gives a description of the BCT meeting and call activities. At the BCT kick-off meeting, HPRN staff and members of the CAC received a comprehensive education about the PCMH from a local expert, including the forces driving PCMH programme development and policies, the model's components and the intended impact on patient care. A facilitated problem-solving session followed, during which CAC members began to identify key information and constructs to begin developing messages that would make the traditional, complicated medical jargon associated with the PCMH more accessible and meaningful for patients and members in their communities.

Table 1.

PCMH boot camp translation schedule

| Meeting | Time | Date |

|---|---|---|

| PCMH boot camp translation kick-off | ||

| Face-to-face meeting | 9 a.m. to 3 p.m. | 11 December 2010 |

| Conference call | 4.30 p.m. to 5 p.m. | 23 February 2011 |

| Conference call | 4.30 p.m. to 5 p.m. | 3 March 2011 |

| Conference call | 4.30 p.m. to 5 p.m. | 15 March 2011 |

| Face-to-face meeting | 4.30 p.m. to 5 p.m. | 4 May 2011 |

| Conference call | 4.30 p.m. to 5 p.m. | 28 June 2011 |

| Conference call | 4.30 p.m. to 5 p.m. | 7 July 2011 |

| Face-to-face meeting | 9 a.m. to 12 noon | 20 July 2011 |

| Presentation (North American Primary Care Research Group) | 14 November 2011 | |

| E-mails | Multiple | 31 January to 31 December 2011 |

Several conference calls were held over the next 3 months. The community–academic partnership struggled with how to translate the technical PCMH language into a meaningful discussion. After several difficult conference calls, the group chose to conduct an appreciative inquiry into the meaning of ‘patient centred’.16 Each community member was asked to tell a story of a successful interaction with their healthcare provider – examples of interactions that represented the positive ideas they had heard about the medical home. Community members were encouraged to ask their family members and neighbours for stories of successful healthcare experiences. Each of these anonymous stories was told in the group and the written narratives were shared among the members. Elements of successful interactions were pulled from the stories as well as quotes and short one-liners. This modified appreciative inquiry methodology reinvigorated the group and propelled the completion of the BCT.

Results

Community members participating in this project have a very different view of the value of the PCMH than the more traditional academic or medical perspective. They placed emphasis on the patient–physician relationship and concluded that the components of the PCMH should be done in service to that relationship. The patient population did not need to be concerned with the more technical supporting components of the PCMH, but rather how relationships with personal physicians are facilitated by the PCMH.

Words or catchphrases that the CAC considered for use in BCT materials included:

You can have a better relationship with your doctor.

Are you tight with your doctor?

Spend more quality time with your doctor.

Stories collected through the modified appreciative inquiry revealed idealistic scenarios in which the physician knows the patient's social situations that may be affecting their health:

He knows what I have gone through and remembers to ask if there are any new developments.

They demonstrated the idea of having a physician who knows the whole family:

He took my mother seriously, he listened to her kids, and he communicated with us, communicated with us outside of the office (via email and phone call).

They demonstrated the idea of coordination and a team-based approach to their care:

… if the medical staff, including administrative personnel, make me feel like they care about me and want me to get better, the visit is a huge success.

The personnel in the office from receptionists to doctor projected a true care for us as if we were their neighbour next door. I received the impression that they truly cared for me as an individual and were interested in our total health…

They highlighted efficient and evidence-based medicine:

… I am getting top-notch, up to date, medical care. I wish everyone could have this. It feels good to know that I can trust my provider to recommend the drugs and tests that will actually make me healthier. Not more, not less.

They identified patient education and role in health management:

I can care for myself between visits.

I can keep track of my blood tests.

I learned what an HgbA1c is.

Although the collected stories highlight ideal patient experiences that may only be individual strengths of the various practices, they nonetheless illustrate what the PCMH strives to achieve: ‘… strengthening the physician–patient relationship by replacing episodic care based on illnesses and patient complaints with coordinated care and a long-term healing relationship.’17

Limitations

This study has some important limitations. First, it was not a random sample of community members. The number of community members providing stories is relatively small, approximately 30, and may not be large or diverse enough to fully represent the population of interest. Furthermore, this study is limited to rural community members of the eastern plains of Colorado and application of its findings beyond this geographic region requires further investigation.

Finally, this study was performed with individuals from communities in which the PCMH was not yet implemented or only partially implemented. This project was not intended to gain an understanding of the effect of the PCMH on current care. Rather, the goal was to obtain patients' perspectives of what the PCMH might mean to them in the future and to use this knowledge to personalise the implementation of the PCMH into their communities and educate other members of the community.

There is nothing like looking, if you want to find something. You certainly usually find something, if you look, but it is not always quite the something you were after. (JRR Tolkien)

Discussion

The goal of the project was to use the BCT process to engage community members in obtaining a comprehensive understanding of the purpose and components of the PCMH to create locally relevant and meaningful language related to the PMCH and promote increased participation by the patients and providers in the local region. Although the final messages appear to be basic common sense, the results were quite different from what was expected. Rather than translating specific key technical PCMH components (group visits, disease registries, etc.), community members really focused on the meaning of ‘patient centred.’ How did patient centred intersect with the current values and components of the formal PCMH? Simply translating the current PMCH components into more common language was insufficient. The need for different messages about the PCMH for patients and providers became clear – for example, although the PCMH components of physician-directed medical practice, team care, quality and safety were considered vital, community members felt that they should exist behind the scenes and should not be an explicit part of the patient experience. These components should be in service to the most essential element of the PCMH – the relationship between the patient and their provider. This sense of relationship derived directly from the appreciative inquiry narratives shared by community members.

These findings add to growing literature on patient experiences of health care. As with community-development work described by Fisher, the assets-based approach used by this project identified and emphasised strengths and generated community-driven and relevant results that may facilitate meaningful conversations with local people to improve healthcare delivery. Another study reporting on a national sample found that patients with a usual source of care had a more positive experience.18 Specifically, patients with a usual source of care were more likely to report that their provider listened to them, showed respect and spent enough time with them. This usual source of care appears to be a measure of an important element of a good relationship. More recently, a study examining patients from a medically underserved part of Hawaii found that patient perception of quality of care was directly related to the physician–patient relationship. A good relationship was characterised by interpersonal skills.19

The findings of this project and the other studies take on deeper meaning when one realises that there have been two dilemmas that have haunted the PCMH model since its conception. The first dilemma is balancing efforts to improve coordination, cost, and efficiency of health care delivery with maintaining or improving quality of care. The second dilemma is ensuring that the PCMH model is in fact ‘patient-centred’ rather than physician-centred. While maintaining and improving health care quality has always been a primary goal of the PCMH model, critics question if its implementation doesn't ultimately distract or take away from patient-centredness.

Research performed to address the second dilemma has been mixed. Some studies suggest that, in addition to positive health outcomes and decreased cost, there is also improved patient satisfaction associated with the PCMH model.7,20 However, Jaen et al found that despite improved quality of care, patient satisfaction declined.21 Another observational study failed to find any association between PCMH implementation and patient satisfaction.22 Although the reasons for these mixed results are not clear, the timing of the evaluation in relationship to PCMH implementation is at least partially related. These findings may also be related to the patient perspective and the degree of patient involvement in implementation. PCMH may be an innovative and important model of health care for reaching the triple aim of improved health, lower cost and better patient experience – however, it is unlikely that a ‘one size fits all’ approach will work for all, especially in rural practices and communities. Further, although the physician perspective on PCMH is essential for full implementation, provider input may not be sufficient to truly transform primary care into a patient-centred experience. As Fisher argues, community engagement and responsiveness to community needs are essential to improving health services and outcomes.15 The PCMH model may benefit from a local interpretation and tailored approach that includes the patient perspective in content and implementation, as identified by this project.

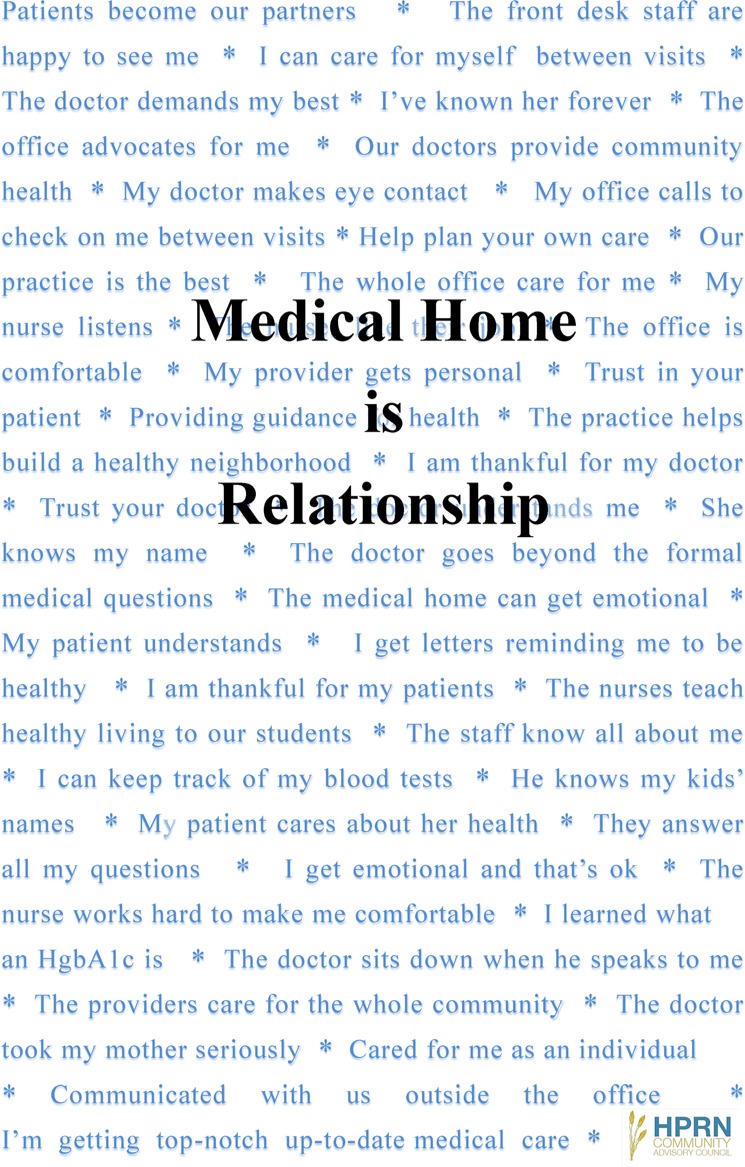

The HPRN CAC developed a PCMH poster that aims to describe the core value they feel is essential: Medical Home is Relationship (Figure 1). Posters were disseminated to HPRN practices to help clinical providers and staff with the language to further educate patients about the PCMH. Other materials and implementation strategies will include this sine qua non concept in all HPRN PCMH activities.

Figure 1.

Relationship poster.

Conclusion

This project provided a clearer picture of what a patient population values in their health care delivery. This insight will help guide the implementation of the PCMH model into practices. Ultimately, the link between patients and their primary care provider can make the house a home. The patient perspective may hasten the move toward true patient-centred care.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors express their gratitude to the members of the High Plains Research Network Community Advisory Council for all of their time, dedication and work in helping with the development of the patient-centred Medical Home message and for their continued dedication to the health care of the rural Eastern Colorado communities. We also thank the additional community members who provided stories of successful interaction with their provider and the Patrick and Kathleen Thompson Endowed Chair for Rural Health and Health TeamWorks (Denver, Colorado) for their support of this project.

Contributor Information

Marc Ringel, High Plains Research Network, Department of Family Medicine, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, CO, USA.

Steve Winkelman, High Plains Research Network, Community Advisory Council, USA.

Susan Gale, High Plains Research Network, Department of Family Medicine, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, CO, USA.

John M. Westfall, High Plains Research Network, Department of Family Medicine, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, CO, USA and Colorado HealthOP, Denver, CO, USA.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), American College of Physicians (ACP) and American Osteopathic Association (AOA) (2007) Joint Principles of the Patient-Centered Medical Home. www.aafp.org/online/etc/medialib/aafp_org/documents/policy/fed/jointprinciplespcmh0207.Par.0001.File.tmp/022107medicalhome.pdf (accessed 17/07/11).

- 2.Stange KC, Nutting PA, Miller WL. et al. (2010) Defining and measuring the patient-centered medical home. Journal of General Internal Medicine 25:601–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pugno PA. (2010) One giant leap for family medicine: preparing the 21st-century physician to practice patient-centered, high-performance family medicine. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine 23 Suppl 1:S23–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferrante JM, Balasubramanian BA, Hudson SV, Crabtree BF. (2010) Principles of the patient-centered medical home and preventive services delivery. Annals of Family Medicine 8:108–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roby DH, Pourat N, Pirritano MJ. et al. (2010) Impact of patient-centered medical home assignment on emergency room visits among uninsured patients in a county health system. Medical Care Research and Review 67:412–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nutting PA, Dickenson WP, Dickenson LM. et al. (2007) Use of chronic care model elements in association with higher-quality care for diabetes. Annals of Family Medicine 5:14–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reid RJ, Coleman K, Johnson EA. et al. (2010) The group health medical home at year two: cost savings, higher patient satisfaction, and less burnout for providers. Health Affairs 29:835–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palfrey S, Sofis LA, Davidson EJ. et al. (2004) The pediatric alliance for coordinated care: evaluation of amedical home model. Pediatrics 113:1507–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gill JM, Fagan HB, Townsend B, Mainous AG. (2005) Impact of providing a medical home to the uninsured: evaluation of a Statewide program. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 16:515–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martsolf GR, Alexander JA, Shi Y. et al. (2012) The patient-centered medical home and patient experience. Health Service Research 47:2273–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berckelaer AV, DiRocco D, Ferguson M. et al. (2012) Building a patient-centered medical home: obtaining the patient's voice. Journal of the American Board of Family Physicians 25:192–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Westfall JM, Fagnan LJ, Handley M. et al. (2009) Practice-based research is community engagement. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine 22:423–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Westfall JM, VanVorst RF, Main DS, Herbert C. (2006) Community-based participatory research in practice based research networks. Annals of Family Medicine 4:8–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Norman N, Bennett C, Cowart S. et al. (2013) Boot camp translation: a method for building a community of solution. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine 26:254–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fisher B. Community development: health gain and service change. Do it now! London Journal of Primary Care 6:154–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Appreciative Inquiry Commons. http://appreciativeinquiry.case.edu (accessed 13/12/13).

- 17.NCQA (2011) Patient centered medical home: health care that revolves around you. www.ncqa..org/portals/0/PCMH2001%withCAHPSInsert.pdf (accessed 09/12/12).

- 18.DeVoe JE, Wallace LS, Pandhi N, Solotaroff R, Fryer GE., Jr (2008) Comprehending care in a medical home: a usual source of care and patients perceptions about healthcare communication. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine 21:441–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takane AK, Hunt SB. (2012) Transforming primary care practices in a Hawai'i island clinic: obtaining patient perceptions on patient centered medical home. Hawai'i Journal of Medicine & Public Health 71:253–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reid RJ, Fishman PA, Onchee Y. et al. (2009) Patient-centered medical home demonstration: a prospective, quasi-experimental, before and after evaluation. American Journal of Managed Care 15(9):71–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jaen CR, Ferrer RL, Miller WL. et al. (2010) Patient outcomes at 26 months in the patient-centered medical home national demonstration project. Annals of Family Medicine 8:S57–S67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martsolf GR, Alexander JA, Shi Y. et al. (2012) The patient-centered medical home and patient experience. Health Service Research 47:2273–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]