Abstract

Objective

There has been a rapid increase in the use of waterpipe tobacco and non-tobacco based shisha in many countries. Understanding the impact and effects of second-hand smoke (SHS) from cigarette was a crucial factor in reducing cigarette use, leading to clean indoor air laws and smoking bans. This article reviews what is known about the effects of SHS exposure from waterpipes.

Data sources

We used PubMed and EMBASE to review the literature. Articles were grouped into quantitative measures of air quality and biological markers, health effects, exposure across different settings, different types of shisha and use in different countries.

Study selection

Criteria for study selection were based on the key words related to SHS: waterpipe, hookah, shisha and third-hand smoke.

Data extraction

Independent extraction with two reviewers was performed with inclusion criteria applied to articles on SHS and waterpipe/hookah/shisha. We excluded articles related to pregnancy or prenatal exposure to SHS, animal studies, and non-specific source of exposure as well as articles not written in English.

Data synthesis

A primary literature search yielded 54 articles, of which only 11 were included based on relevance to SHS from a waterpipe/hookah/shisha.

Conclusions

The negative health consequences of second-hand waterpipe exposure have major implications for clean indoor air laws and for occupational safety. There exists an urgent need for public health campaigns about the effects on children and household members from smoking waterpipe at home, and for further development and implementation of regulations to protect the health of the public from this rapidly emerging threat.

Keywords: Environment, Non-cigarette tobacco products, Secondhand smoke

Introduction

While cigarette use has decreased dramatically in recent years, there has been a marked increase in adolescent and young adult use of alternative, non-cigarette tobacco products. The total consumption of cigarettes in the USA decreased by 33% between 2000 and 20111; however, estimations from this same time period show a 123% increase in the consumption of alternative tobacco products, including hookahs (waterpipes), cigarillos, cigars, bidis, kreteks and smokeless tobacco (snuff, dip, snus and chewing tobacco).1

Inhalation of second-hand smoke (SHS) by non-smokers has been associated with multiple diseases in paediatric and adult populations. Such evidence is especially troubling given the 2006 report by the US Department of Health and Human Services, which estimated that 60% of US non-smokers are exposed to SHS.2 Exposure occurs through several distinct routes: sidestream smoke, mainstream smoke, or smoke that has permeated the air of the surrounding environment. Sidestream smoke is the smoke discharged from the lit end of a burnt tobacco product; mainstream smoke is the smoke that is inhaled by a smoker and subsequently exhaled into the environment during a period of active smoking.3 Another route of exposure by non-smokers is third-hand smoke (THS), which is defined as the residual matter from tobacco smoke that collects on surfaces and in dust.4 While SHS and THS have historically been associated with cigarette smoke, there has recently been an alarming rise in alternative non-cigarette tobacco use, raising the important question of whether these products also generate harmful SHS and THS.

Hookah (also called waterpipe, nargile or hubble-bubble) is perceived to be safer and less addictive than cigarettes, despite growing evidence that hookah smoke is potentially more harmful than cigarette smoke.5–8 This is worrisome given that the 2011 National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS) found a 7.3% prevalence of waterpipe use among adolescents in the USA (roughly 2 million adolescents).9 This study also showed that 53.1% of adolescents living in a home with a hookah user reported trying hookah. Another recently published study using a nationally representative sample from Monitoring the Future showed that adolescents from more highly educated families and who had more discretionary money were more likely to use hookahs.10 A study of pregnant women in Jordan showed that the household accounts for nearly 49% of second-hand and third-hand waterpipe exposure, which highlights the need for additional research on home exposure and populations that may be at particular risk of exposure within the home, such as children.11

Methods

We conducted a primary literature search in two separate databases; PubMed and EMBASE. We used the following search terms:

passive smoking, second hand smoke, second hand smoker, second hand smokers, second-hand smoke, third hand smoke, waterpipe, waterpipes, water-pipe, water-pipes, hubble-bubble, hookah narghile, shisha, qalyan.

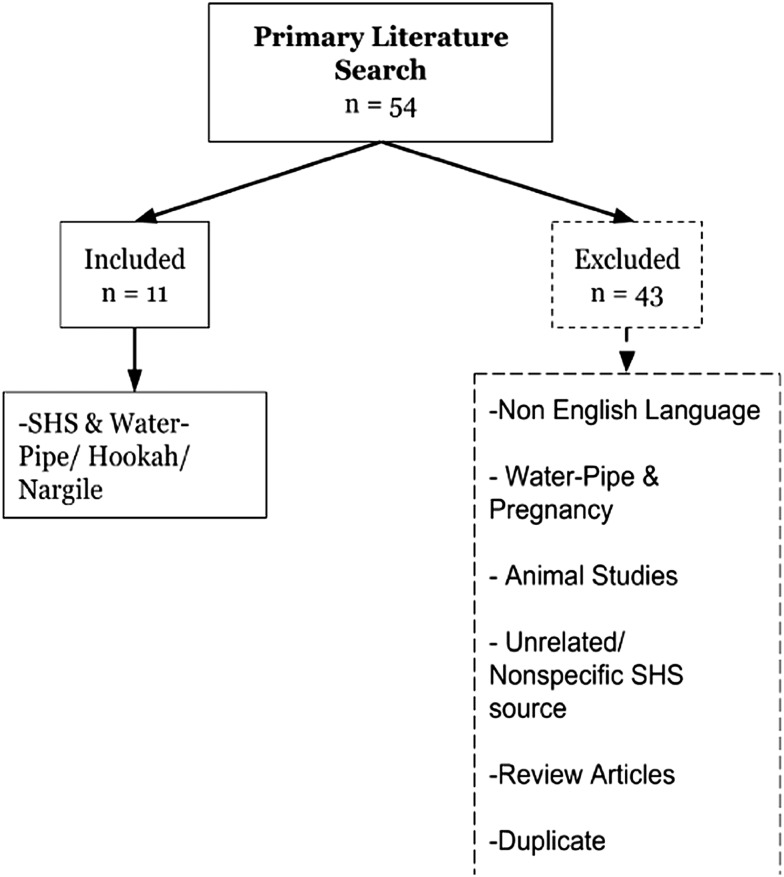

We combined the list of articles found from the two databases. Two reviewers went through the title and abstract of each article for relevance. We included articles with original research on SHS or THS from waterpipes (figure 1). We excluded all review articles and original research articles that were written in languages other than English, were related to waterpipe use and pregnancy, involved animal models, studied SHS from a non-specific sources, or were unrelated.

Figure 1.

Search strategy algorithm (SHS, second-hand smoke).

The small number of articles that we found precluded conducting a meta-analysis. Instead, we simply present them as a narrative review.

Results

We found a total of 54 articles that were manually reviewed by two researchers to yield a total of 11 relevant articles. The reasons for excluding articles were: not published in the English language (n=3); focused on pregnancy and waterpipes (n=4); had a non-specific source of SHS either from cigarette, waterpipe, or other tobacco sources (n=5); were unrelated to the topic (n=26); review articles (n=3); non-human studies (n=1) and duplicate articles (n=1). See figure 1 for the search strategy algorithm. We have summarised the articles that were included in the narrative review in table 1.

Table 1.

Articles obtained from the literature search

| Lead author | Year | Country | Type and number of subjects (or target places) | Study design | Outcomes measured | Summary | Main findings | Exclusion of other sources of second-hand smoke |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cobb et al15 | 2013 | USA | 28 venues in Virginia (17 waterpipe cafes, 5 restaurants permitting cigarette smoking and 6 smoke-free restaurants (5 with valid data)) | Observational | PM with a 2.5 μm aerodynamic diameter or smaller (PM2.5) | Waterpipe café smoking rooms have a hazardous level of PM2.5 that could be potentially harmful to customers and workers | PM2.5 was greater in waterpipe café smoking rooms (374 μg/m3, n=17) compared with waterpipe café non-smoking rooms, cigarette smoking-permitted restaurant smoking rooms, cigarette smoking-permitted restaurant non-smoking rooms, and smoke-free restaurants | Measurements began 5 min prior to entering the venue and ended 5 min after exiting each venue to compare outdoor ambient air to the air inside the venue |

| Daher et al7 | 2010 | Lebanon | 4 repeated waterpipe-smoking sessions and 4 repeated cigarette trials | Observational | Sidestream smoke from waterpipes or cigarettes for ultrafine particles, carcinogenic polyaromatic hydrocarbons, volatile aldehydes, and CO | Second-hand waterpipe smoke emits significant harmful substances | Sidestream waterpipe smoke had nearly 4 times the carcinogenic PAH, 4 times the volatile aldehydes and 30 times the CO of 1 cigarette | Smoking-machine and environmental chamber approach allowed for repeated measurements under controlled conditions and few confounding variables |

| Fiala et al14 | 2012 | USA | 10 indoor hookah lounges in Oregon | Observational | PM smaller than 2.5 μm in diameter | Air quality in hookah lounges in Oregon ranges from unhealthy to hazardous | 2 hookah lounges had peak PM2.5 measurements in the hazardous EPI air quality category, 4 were very unhealthy, and 4 were unhealthy. None had good air quality | Measurements began prior to entering the venues and ended after exiting the venues to compare the outdoor ambient air to the air in the hookah lounges |

| Fini et al12 | 2013 | Iran | 387 total persons (172 male and 215 female) | Observational | Demographic characteristics and questions related to environmental tobacco smoke exposure | A large proportion of citizens of Bandar Abbas city are exposed to environmental tobacco smoke | The most common places that people were exposed to hookah smoke were in the home (93.4%), coffee shops (17.1%) and restaurants (11.5%). People were exposed to environmental cigarette smoke in public vehicles (52.2%) and the home (31.3%) | NA |

| Hammal et al19 | 2013 | Canada | 3 replicates of each of the 3 brands were analysed. 6 randomly selected waterpipe cafes were visited | Observational | Chemical constituents of tobacco-free products used in waterpipes, waterpipe emission under controlled conditions, and air quality markers in waterpipe cafes | Second-hand smoke from herbal shisha contains carcinogens equal to or greater than that found in cigarettes and may be hazardous | Second-hand waterpipe smoke had significant levels of aromatic hydrocarbons, CO, PM2.5 and trace metals | Measurements taken outdoors before and after the visit for comparison |

| Kassem et al21 | 2014 | USA | 24 homes were visited 3 times during a 7-day period | Observational | Levels of indoor air and surface nicotine, child uptake of nicotine, the carcinogen NNK, and the toxicant acrolein by measuring corresponding metabolites cotinine, NNAL and NNAL-glucuronides and 3-HPMA | Children living in homes of hookah smokers are exposed to nicotine, the carcinogen NNK and the toxicant acrolein, which pose a threat to long-term health | Compared with homes of non-smokers, children living in homes of daily or weekly/monthly hookah smokers had significantly elevated levels of cotinine and NNAL, with children of daily smokers also having significantly elevated 3-HPMA | 2 air samples were collected with passive diffusion monitor badges in the living room and child's bedroom. A blank non-analysed badge was placed in a third room |

| Markowicz et al18 | 2014 | Sweden | Filters from 10 replicate sessions of waterpipe smoking | Observational | Microbial compounds in waterpipe smoke | Waterpipe smoke creates a bioaerosol similarly to cigarette smoke | In a 1–2 h session, second-hand smoke from waterpipes produced a concentration of 2.8 pmol/m3 of LPS. Ergosterol was not detected. This is comparable to 22.2 pmol/m3 of LPS and 87.5 ng/m3 of ergosterol from smoking 5 cigarettes | NA |

| Tamim et al22 | 2003 | Lebanon | 625 students from 5 different private schools | Observational | Information on demographic, in-home smoking, and students’ respiratory tract illnesses (cough, wheezing, runny nose, or nasal congestion) | Children exposed to second-hand waterpipe smoke may develop respiratory problems | 22.6% (12/53) had wheezing or nasal congestion, 11.3% (6/53) had just wheezing, and 15.1% (8/53) had just nasal congestion | NA |

| Zaidi et al17 | 2011 | Pakistan | 39 indoor venues (13 shisha smoking, 13 cigarette smoking, and 13 non-smoking) | Observational | Mean concentration of PM2.5 | Air quality at shisha smoking venues had hazardous air quality | Shisha smoking venues had an average PM2.5 of 1745 μg/m3 | Venues with other sources of indoor air pollution and non-air-conditioned venues exposed to outdoor pollution were excluded. Samples were obtained before entering the venues to calibrate the device |

| Zeidan et al23 | 2014 | Lebanon | 147 people surveyed | Observational | Questionnaires on sociodemographic characteristics, respiratory symptoms and exposure to second-hand smoke. Exhaled CO levels | Second-hand waterpipe smoke may cause respiratory symptoms in non-smokers | Of the 147 surveyed, 48 were exposed only to second-hand waterpipe smoke. 58% reported a chronic cough | Measurements of expired-air CO were calibrated with local environmental CO concentration |

| Zhang et al16 | 2013 | Canada | Indoor (n=12) and outdoor (n=5) air quality was assessed in Toronto, Canada waterpipe cafes | Observational | Air nicotine, fine PM less than 2.5 μm in diameter, and ambient CO | Air quality of waterpipe cafés is a health hazard. Waterpipe smoking should be eliminated from indoor and outdoor hospitality venues | Indoor values were 1419 µg/m3 for PM2.5, 17.7 ppm for ambient CO, and 3.3 µg/m3 for air nicotine. Outdoor values were 80.5 µg/m3 for PM2.5, 0.5 ppm for ambient CO, and 0.6 µg/m3 for air nicotine | Measurements taken as far as possible from kitchen areas and open windows to reduce contamination. Background readings obtained outdoors in areas without nearby smokers |

3-HPMA, 3-hydroxypropylmercapturic acid; CO, carbon monoxide; EPI, Environmental Performance Index; LPS, lipopolysaccharides; NA, not applicable; NNAL, 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanol; NNK, 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone; PAH, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon; PM, particulate matter.

Venues where individuals are exposed to waterpipe smoke

We found one study that assessed exposure to waterpipe smoke and cigarette smoke among 387 people in Iran.12 The most common places that people were exposed to hookah smoke were in the home (93.4%), coffee shops (17.1%) and restaurants (11.5%). In this same article from Iran, people were exposed to environmental cigarette smoke more often in public vehicles (52.2%) and the home (31.3%).

Measures of SHS from waterpipes: studies of air quality and biological absorption

Air quality

The composition of waterpipe smoke has been shown to include a number of potentially harmful toxins and chemicals. However, there has been a paucity of studies to date, with many of these studies measuring air quality only in hookah lounges. There is limited data on ambient air quality in other settings and only one study identified in this review that measured air quality specifically in the home.

Particulate matter

We found only three articles in the USA that assessed levels of particulate matter (PM) resulting from waterpipe smoke. Air quality in the USA is defined by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) based on the Air Quality Index (AQI) that is dependent on the peak PM concentration (PM2.5(μg/m3)). This index ranges from a rating of good (0–50) to hazardous (301–500); all higher readings surpassing 500 are still considered to be hazardous.13 In Oregon, Fiala et al14 analysed the air quality in 10 hookah lounges, all of which were found to have a minimum index rating of unhealthy (AQI 151–200), with 2 reaching the hazardous level. In Virginia, Cobb et al15 compared SHS among a variety of venues with differing smoking rules. Of great concern, the PM2.5 concentration was greater in the waterpipe cafes (mean of 374 μg/m3, AQI hazardous) compared with establishments where cigarette smoking, but not use of waterpipes, was occurring (mean of 119 μg/m3, AQI unhealthy). Furthermore, the non-smoking sections of the waterpipe cafe were found to have a similar mean (123 μg/m3, AQI unhealthy) to restaurants where cigarettes are smoked.

Two studies from other countries have also analysed levels of PM, as well as other indicators of air quality such as carbon monoxide (CO) and nicotine. In Toronto, Canada, Zhang et al16 measured the ambient air in indoor and outdoor waterpipe venues. Indoor venues were shown to have hazardous levels of PM2.5 with a significant mean of 1419.4 μg/m3, about 69 times higher than that of ambient air, whereas outdoor venues had poor levels of PM2.5 with a significant mean of 80.5 μg/m3, still above the EPA ‘good’ level of 0–59. A study conducted in Pakistan by Zaidi et al17 collected data from 13 hookah venues and found an average PM2.5 of 1745 μg/m3.

Potentially dangerous toxic exposures other than PM

Another way of approximating air quality is to look at sidestream smoke. Although it is likely that sidestream smoke is more concentrated than ambient air in outdoor spaces, it may provide valuable information on additional features to consider for future ambient air studies. A study by Daher et al7 compared the sidestream emissions from a single waterpipe session to that of one cigarette. The authors found that the sidestream smoke of waterpipe smoke had nearly four times the carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH), four times the volatile aldehydes and 30 times the CO of one cigarette. With regard to the biological agents studied, Markowicz et al18 discovered the presence of bacterial lipopolysaccharides (LPS) in SHS during a waterpipe smoking session.

A study by Hammal et al19 analysed the mainstream and sidestream smoke from three products of herbal shisha and found that mainstream and sidestream smoke emissions from herbal shisha contain carcinogens equal to or greater than those found in tobacco products. The results showed significant levels of aromatic hydrocarbons, CO, PM2.5 and trace metals.

Nicotine in ambient air and metabolites of nicotine are often thought of merely as measures of exposure. However, an extensive body of literature demonstrates the profound negative health consequences of nicotine exposure, such as its potential for addiction to itself and other agents and its cardiovascular effects.20 A recent study by Kassem et al21 found that nicotine levels in indoor air collected from the homes of daily hookah smokers were significantly higher than in the air collected from the homes of non-smokers.

Biological indicators

In contrast to studies conducted in hookah bars, we have found only one study to date that has explored hookah smoke in homes. The previously mentioned study by Kassem et al21 explored the effects of SHS on children under 5 years of age in the homes of hookah users. The inhaled levels of the following potentially harmful chemicals found in SHS were measured in urine: nicotine, acrolein, and 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK). These chemicals were measured according to their metabolites cotinine, 3-hydroxypropylmercapturic acid (3-HPMA) and 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanol (NNAL), respectively. Compared with homes of non-smokers, children living in homes of daily or weekly/monthly hookah smokers had significantly elevated levels of cotinine and NNAL, with children of daily smokers also having significantly elevated 3-HPMA.

Health effects of SHS exposure from waterpipes

Of course, the importance of exposure is the potential for untoward health effects. However, to date, the studies have been limited to acute effects, where as we know from a century of research on cigarettes that the most dangerous effects are long term. We found two studies from Beirut, Lebanon that reported on health effects of SHS exposure from waterpipe use. Tamim et al22 surveyed 625 students (mean age of 13 years) for details of their exposure and respiratory symptoms. They found that 8.5% (53 students) reported being exposed to SHS from waterpipe use at home due to parental use. Of the respiratory symptoms surveyed, 22.6% (12/53) had wheezing or nasal congestion when exposed to SHS from waterpipe use at home, compared with 11.2% (21/187) who had no exposure to any SHS at home; 11.3% (6/53) vs 5.3% (10/187) had just wheezing; and 15.1% (8/53) vs 7.5% (14/187) had just a nasal congestion. Zeidan et al23 surveyed 147 non-smokers (age range 18–35 years) on their demographics, exposure to SHS from either a waterpipe or cigarettes, and respiratory symptoms. Of the 147 respondents, 48 were exposed to only waterpipe SHS, and a majority of these people (58% or 29/48) reported having a chronic cough. This finding is in comparison to 49 of the 147 who had no exposure to SHS, with only 16.3% of people with a chronic cough.

Discussion

We found that SHS from waterpipes results in exposure to hazardous levels of PM according to the EPA's AQI, as well as carcinogenic PAH, CO, nicotine and bacterial LPS. A recent study in New York City by Zhou et al24 (published by our research team after the original literature search) found that overall levels of indoor air pollution increased with rising numbers of active hookahs smoked and that the mean PM2.5 level was 694 μg/m3 (AQI hazardous). This same study found a substantial number of potentially toxic exposures that were identified from air samples collected in hookah bars, such as CO, black carbon, elemental carbon, organic carbon, and nicotine, in addition to fine PM and total gravimetric PM. Furthermore, children living in the homes of hookah smokers had elevated levels of cotinine, NNAL and 3-HPMA depending on frequency of use. We did not find any studies reporting on morbidity or mortality directly attributable to SHS or THS from hookah use.

As noted, there is evidence indicating that active waterpipe smoking is not as harmless as was previously believed.5–7 Furthermore, the cancer risk profile may be different in waterpipe-exposed and cigarette-exposed populations due to production of different carcinogens.25 The documented health effects of SHS from cigarettes have had a profound impact on public perception of smoking as well as the passage of policies to protect non-smokers. SHS causes lung cancer and coronary artery disease in adults,2 26 as well as sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), recurrent ear infections and asthma exacerbations, and it is also associated with numerous other health problems in the paediatric population.2 According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in 2000, 80% of adults recognised that SHS from cigarettes was not only harmful but they also believed that non-smokers should be protected in the workplace from such exposure.2 Comparable awareness and beliefs regarding hookah-related SHS are currently woefully lacking.

There is limited literature to date focusing on the impact of SHS exposure from waterpipe use on non-smokers. Further environmental measures of carcinogens and toxins are needed in homes of users as well as in venues that allow hookah use. Thus far, concentrations of CO, thiocyanate or nicotine have been proposed as indirect markers to measure SHS emitted from waterpipes. As described above, a study in 2014 of 24 households with hookah-only smokers or non-smokers found higher air nicotine levels in the homes of hookah-only smokers compared with the homes of non-smokers.21 Similarly, indoor environments where waterpipe was smoked had higher pollutant levels. To date, many studies have found increased pollutant levels in indoor environments where waterpipes are smoked.7 27 28 For example, sidestream smoke analysis showed that a single session of waterpipe use was associated with four times the carcinogenic PAH, four times the volatile aldehydes and 30 times the CO when compared with one cigarette.7 Additional studies are needed to further elucidate the health risk for non-smokers in close proximity to waterpipe smoke.

A number of policies currently exist that aim to control environmental tobacco exposure. These policies include, but are not limited to, smoke-free environments, the regulated sale of tobacco products and tobacco-related advertising as well as restricted sales of tobacco products to minors.29 In addition, increased taxation has a marked effect on cigarette smoking. The WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), which was established in 2003 in response to the global tobacco epidemic, included many of these policy initiatives. However, few pieces of waterpipe-specific regulations were included in the FCTC, and therefore waterpipe use remains largely unregulated.29 30 According to the American Lung Association, it is imperative to address the health risks to active and passive smokers secondary to waterpipe, especially considering that smoke-free laws often exempt hookah bars from regulation.30 As an example, the USA does not currently have federal tobacco control policies that limit waterpipe access by minors or require visible warning labels on waterpipe products. This lack of regulation may perhaps lead users to believe that waterpipe smoking is less addictive and harmful to their health.29

Clearly, much more research is urgently needed to inform efforts to implement national regulations. It should focus on acute effects (such as on cardiopulmonary or inflammatory changes), chronic effects (such as cancers and long-term cardiac and pulmonary problems), and the potentially unique effects on children. On the basis of data that already exist, we believe that SHS from hookah smoking poses a threat comparable to or even greater than that emanating from cigarette smoking. New policies and legislation should be implemented to protect people from the harmful effects of SHS from waterpipes.

What this paper adds.

The recognition of this epidemic is recent, and consequently our knowledge is limited.

To date, studies have been able to demonstrate that air in places where hookah is smoked contains high levels of dangerous compounds and that people absorb harmful substances from second-hand waterpipe smoke.

The few existing studies suggest negative acute effects on people's health from exposure to second-hand waterpipe smoke.

Footnotes

Contributors: SRK and SD conducted the systemic review and drafted the manuscript. SS and MW provided revisions.

Funding: This work was supported in part by the NYU/Abu Dhabi Public Health Research Center.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: For additional data email the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Consumption of cigarettes and combustible tobacco—United States, 2000–2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2012;61:565–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Health Consequences of Involuntary Exposure to Tobacco Smoke: A Report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health Atlanta, GA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.International Agency for Research on Cancer. Tobacco smoke and involuntary smoking. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum 2004;83:1–1438. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sleiman M, Gundel LA, Pankow JF, et al. Formation of carcinogens indoors by surface-mediated reactions of nicotine with nitrous acid, leading to potential thirdhand smoke hazards. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010;107:6576–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cobb C, Ward KD, Maziak W, et al. Waterpipe tobacco smoking: an emerging health crisis in the United States. Am J Health Behav 2010;34:275–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noonan D, Kulbok PA. New tobacco trends: waterpipe (hookah) smoking and implications for healthcare providers. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 2009;21:258–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daher N, Saleh R, Jaroudi E, et al. Comparison of carcinogen, carbon monoxide, and ultrafine particle emissions from narghile waterpipe and cigarette smoking: sidestream smoke measurements and assessment of second-hand smoke emission factors. Atmos Environ (1994) 2010;44:8–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.St Helen G, Benowitz NL, Dains KM, et al. Nicotine and carcinogen exposure after waterpipe smoking in hookah bars. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2014;23:1055–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amrock SM, Gordon T, Zelikoff JT, et al. Hookah use among adolescents in the United States: results of a national survey. Nicotine Tob Res 2014;16:231–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palamar JJ, Zhou S, Sherman S, et al. Hookah use among US high school seniors. Pediatrics 2014;134:227–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Azab M, Khabour OF, Alzoubi KH, et al. Exposure of pregnant women to waterpipe and cigarette smoke. Nicotine Tob Res 2013;15:231–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fini AA, Aghamolaei T, Dehghani M, et al. Environmental Tobacco Smoke (ETS) exposure in people over 15 years old in Bandar Abbas. Biosci Biotechnol Res Asia 2013;10:797–802. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Air Quality Index (AQI). A guide to air quality and your health. US EPA office of air quality planning and standards. Research Triangle Park, NC: Last Updated: May, 2014. http://airnow.gov/index.cfm?action=aqibasics.aqi (accessed 17 Sep 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fiala SC, Morris DS, Pawlak RL. Measuring indoor air quality of hookah lounges. Am J Public Health 2012;102:2043–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cobb CO, Vansickel AR, Blank MD, et al. Indoor air quality in Virginia waterpipe cafes. Tob Control 2013;22:338–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang B, Haji F, Kaufman P, et al. ‘Enter at your own risk’: a multimethod study of air quality and biological measures in Canadian waterpipe cafes. Tob Control Published Online First: 25 Oct 2013. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zaidi SM, Moin O, Khan JA. Second-hand smoke in indoor hospitality venues in Pakistan. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2011;15:972–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Markowicz P, Londahl J, Wierzbicka A, et al. A study on particles and some microbial markers in waterpipe tobacco smoke. Sci Total Environ 2014;499C:107–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hammal F, Chappell A, Wild TC, et al. ‘Herbal’ but potentially hazardous: an analysis of the constituents and smoke emission of tobacco-free waterpipe products and the air quality in the cafes where they are served. Tob Control Published Online First: 15 Oct 2013. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kandel ER, Kandel DB. A molecular basis for nicotine as a gateway drug. N Engl J Med 2014;371:932–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kassem NO, Daffa RM, Liles S, et al. Children's exposure to second-hand and thirdhand smoke carcinogens and toxicants in homes of hookah smokers. Nicotine Tob Res 2014;16:961–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tamim H, Musharrafieh U, El Roueiheb Z, et al. Exposure of children to environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) and its association with respiratory ailments. J Asthma 2003;40:571–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zeidan RK, Rachidi S, Awada S, et al. Carbon monoxide and respiratory symptoms in young adult passive smokers: a pilot study comparing waterpipe to cigarette. Int J Occup Med Environ Health 2014;27:571–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou S, Weitzman M, Vilcassim R, et al. Air quality in New York City hookah bars. Tob Control Published Online First: 16 Sept 2014. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacob P III, Abu Raddaha AH, Dempsey D, et al. Comparison of nicotine and carcinogen exposure with water pipe and cigarette smoking. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2013;22:765–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benjamin R. How tobacco smoke causes disease: the biology and behavioral basis for smoking-attributable disease: a report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Office of Surgeon General, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fromme H, Dietrich S, Heitmann D, et al. Indoor air contamination during a waterpipe (narghile) smoking session. Food Chem Toxicol 2009;47:1636–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maziak W, Rastam S, Ibrahim I, et al. Waterpipe-associated particulate matter emissions. Nicotine Tob Res 2008;10:519–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martinasek MP, McDermott RJ, Martini L. Waterpipe (hookah) tobacco smoking among youth. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 2011;41:34–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.American Lung Association. Hookah smoking: a growing threat to public health issue brief. Smokefree Communities Project, 2011. [Google Scholar]