Abstract

Elevated atmospheric CO2 has been shown to rapidly alter plant physiology and ecosystem productivity, but contemporary evolutionary responses to increased CO2 have yet to be demonstrated in the field. At a Mojave Desert FACE (free-air CO2 enrichment) facility, we tested whether an annual grass weed (Bromus madritensis ssp. rubens) has evolved in response to elevated atmospheric CO2. Within 7 years, field populations exposed to elevated CO2 evolved lower rates of leaf stomatal conductance; a physiological adaptation known to conserve water in other desert or water-limited ecosystems. Evolution of lower conductance was accompanied by reduced plasticity in upregulating conductance when CO2 was more limiting; this reduction in conductance plasticity suggests that genetic assimilation may be ongoing. Reproductive fitness costs associated with this reduction in phenotypic plasticity were demonstrated under ambient levels of CO2. Our findings suggest that contemporary evolution may facilitate this invasive species' spread in this desert ecosystem.

Keywords: Bromus rubens, contemporary evolution, desert ecosystem, elevated atmospheric CO2, genetic assimilation, invasive species, norms of reaction, phenotypic plasticity, stomatal conductance

Introduction

Human-induced changes to the global environment are pervasive (IPCC 2013) and predictions of long-term ecological impacts of these changes may depend on whether organisms can evolve in response to rapid changes in climate (Bradshaw & McNeilly 1991; Geber & Griffen 2003; Franks et al. 2007). The success of invasive species, another important agent of global change, may be due in part to their ability to adapt rapidly to changing environmental conditions (Sakai et al. 2001; Lee 2002). Kingsolver (1996) suggested that demographic characteristics of many invasive species, such as short generation time and large local population size, should facilitate their rapid evolutionary response to global climate change. Rising levels of atmospheric CO2 represent an important component of climate change and, despite the potential for invasive plants to evolve in response to elevated CO2, we have little information on the synergistic interaction between these two major components of global change. Numerous studies have documented pronounced ecological and physiological phenotypic responses of plants to increased CO2 (Ainsworth & Long 2005; Franks et al. 2013) and some studies have demonstrated heritable variation within populations in physiological and growth responses to elevated CO2 (Schmid et al. 1996; Thomas & Jasienski 1996; Case et al. 1998). Nonetheless, there still appears to be little evidence for contemporary evolution in response to elevated atmospheric CO2 (Leakey & Lau 2012). Even in controlled artificial selection experiments under varying CO2 levels, evidence for adaptive evolutionary response is variable and somewhat limited (Tousignant & Potvin 1996; Ward et al. 2000; Collins & Bell 2004; Wieneke et al. 2004; Frenck et al. 2013). In particular, there is a lack of information on contemporary evolutionary responses of plant species to elevated CO2 under realistic field conditions that include complex networks of both abiotic and biotic stressors (Leakey & Lau 2012).

The worldwide network of free-air CO2 enrichment (FACE) facilities represents replicated, large-scale manipulations of atmospheric CO2 under natural field conditions. FACE experiments have provided important information on ecological and physiological responses to elevated atmospheric CO2 (Long et al. 2004). Given rising atmospheric CO2, numerous studies and reviews have indicated that rates of leaf stomatal conductance should decrease, primarily as an adaptive response to conserve water (Tyree & Alexander 1993; Drake et al. 1997; Buckley & Schymanski 2014). Plants typically exhibit reduced stomatal conductance in elevated CO2 conditions because the exaggerated concentration gradient facilitates stomatal uptake of CO2. Lower stomatal conductance results in reduced water loss from transpiration, and C3 plants generally exhibit a greater response to enriched CO2 compared to C4 plants. This differential response suggests that elevated atmospheric CO2 may contribute to changes in community assemblages, although other environmental variables may also affect any relative advantages between C3 and C4 plants as CO2 increases (Bowes 1993). The adaptive importance of reduced stomatal conductance under elevated atmospheric CO2 is further supported by a comprehensive review of physiological results from FACE sites that indicated widespread and consistent phenotypically plastic reductions in stomatal conductance under increased CO2 (Ainsworth & Long 2005). Despite this strong evidence for the adaptive significance of plastic reductions in conductance, none of the studies reported in this review examined potential evolutionary changes in stomatal conductance in response to elevated CO2.

Norms of reaction in phenotypic response or the capacity to acclimate to variation in atmospheric CO2 can also evolve if there is genetic variation in phenotypic plasticity itself (Scheiner 1993). As noted above, a meta-analysis of studies conducted at 12 large-scale FACE sites over 15 years indicated widespread acclimation in several physiological properties (Ainsworth & Long 2005). Although there is some evidence that there may be genetic variance for plasticity in stomatal response (Case et al. 1998), it remains unknown whether any genetic-based capacity for phenotypic plasticity in conductance may change under elevated CO2 levels. A comparison of conductance plasticity between ambient and elevated CO2 populations at a FACE site facilitates the study of possible canalisation in phenotypic response, whereby genetic assimilation (Waddington 1961) may act to “fix” lower conductance in populations exposed to elevated CO2. Demonstration of genetic assimilation in the field has been difficult, but it has been argued that the loss of plasticity and the evolution of a canalised phenotype may occur relatively rapidly and thus may be difficult to detect (Pigliucci et al. 2006). The experimental manipulations in atmospheric CO2 available at FACE sites offer a unique opportunity to detect potentially transient genetic assimilation and the evolution of reduced plasticity in stomatal conductance.

To test if invasive plants can evolve very rapidly (i.e. within 7 years) in response to elevated atmospheric CO2 under natural field conditions, we examined the evolutionary response of an introduced grass species Bromus madritensis ssp. rubens (L.) Husn. (hereafter, referred to as Bromus) to elevated CO2 treatments at the Nevada Desert FACE Facility (NDFF) (Jordan et al. 1999). Bromus is an invasive annual C3 grass that is spreading widely within the south-western United States (Hunter 1991). Previous work on Bromus at NDFF indicates that elevated CO2 elicits plastic changes in physiology, reproductive allocation and seed production (Huxman et al. 1999; Smith et al. 2000; Huxman et al. 2001). These strong phenotypic responses in traits related to fitness suggested that selection for reduced stomatal conductance may be strong and so we examined both evolutionary and plastic responses in Bromus stomatal conductance to elevated atmospheric CO2. For Bromus populations collected from elevated and ambient CO2 FACE rings at the NDFF, we measured stomatal conductance in plants grown under ambient and high CO2 levels in growth chambers. Our central hypothesis was that Bromus populations from elevated CO2 FACE rings should evolve lower conductance rates to better conserve water in the field. By growing plants from these populations under both ambient and high CO2 conditions in growth chambers, we were also able to test whether plasticity in stomatal response varied between populations. In particular, a reduced capacity for conductance plasticity in Bromus populations from elevated CO2 FACE rings would suggest that genetic assimilation for conductance has occurred in these populations. To explore potential adaptive consequences of both genetic and plastic changes in response to elevated CO2, we also measured reproductive output from plants in the growth chambers. If there is a fitness cost to the evolution of reduced conductance or conductance plasticity when CO2 is more limiting, we would expect that elevated CO2 field populations should have a lower reproductive output than ambient CO2 field populations when both populations are grown under ambient CO2. Given previous studies that indicate a plastic growth and reproductive response in Bromus to elevated CO2 (Smith et al. 2000; Huxman et al. 1999), we also expected a plastic adaptive response to high CO2 growth conditions such that, regardless of field population origin, plants growing under high CO2 should exhibit higher reproductive output.

Materials and Methods

The NDFF is located on the Nevada Test Site (36°49′ N, 115°55′ W). On April 28, 1997, the NDFF began exposing circular plots of the Mojave Desert (23 m diameter rings) to ambient (blower controls) or elevated (c. 550 μmol mol−1 CO2) atmospheric CO2 treatments. On 6 May 2004, we collected a minimum of 30 Bromus maternal family seed samples from each of the three ambient and three elevated CO2 FACE rings that had been under continuous treatment for 7 years. Previous research on Bromus has demonstrated some effects of maternal growth environment on phenotypic expression in offspring (Huxman et al. 1998). Thus, before testing for genetic differences between Bromus populations from ambient and elevated CO2 treatments, we controlled for maternal environmental effects by growing out the seeds we collected from the NDFF in an outdoor common garden at the University of California, Davis, California (38°32′ 41″ N, 121°44′ 25″ W). In December 2004, we planted this outdoor common garden using 164 mL conetainers (Stuewe and Sons, Tangent, OR, USA) filled with Yolo loam. Plants were arranged in a randomised complete block design and irrigated with tap water. Overall plant mortality was less than 5% and no maternal families were lost. We then used seed produced from this outdoor common garden to plant experimental populations that replicated maternal families in ambient CO2 (360 μmol mol−1) and high CO2 (700 μmol mol−1) growth chambers (Model PGR15; Conviron, Pembina, ND, USA). Plants in growth chambers were grown in trays with 20.7 cm3 planting cells (ITML, Ontario, Canada). Each planting cell was filled with 15.5 cm3 of Turface MV™ and c. 5 cm3 of Turface QuickDry™ (Profile, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA), coarse- vs. fine-grained forms of calcined montmorillonite clay respectively. The QuickDry™ substrate was amended with solid, slow-release fertilisers (Simplot, Boise, ID, USA) in the forms of polymer-coated potassium nitrate (13-0-43) and triple superphosphate (0-45-0) at the rate of 0.8 g N L−1, 2 g K L−1 and 0.4 g P L−1. Tap water was applied to the plants as needed so water was not limiting. Temperature in the growth chambers was maintained at 22°C and all growth chamber lights (four metal halide, four high-pressure sodium and four incandescent lights) were applied for a 14 h day length including gradual one-hour transitions between light and dark periods.

We repeated the growth chamber trials and switched the CO2 levels in the chambers to avoid confounding chamber effects with treatment effects. We measured stomatal conductance for plants in both trials using a steady-state leaf porometer (Model SC-1; Decagon Devices, Pullman, WA, USA). Inflorescence weights were obtained from the first growth chamber trial where plants were grown to flowering and seed production. Inflorescence weight was used as an index of reproductive fitness because it is highly correlated with viable seed number (r = 0.93; P < 0.0001; n = 45). Although inflorescence weight data were collected only from the first growth chamber trial, we feel that chamber effects were minimal because environmental conditions were very similar between the two chambers. For example, average temperatures (± SD) in high-CO2 vs. low-CO2 chambers were 22.0 ± 0.04°C and 22.0 ± 0.08°C, respectively, while per cent relative humidity was 81.4 ± 2.2 and 81.9 ± 3.0 respectively. In addition, fertilisation and watering regimes were identical. Initial individual seed weight for each maternal plant was used as a covariate in the analysis of both conductance and inflorescence weight to further account for maternal effects. Averaging of the conductance and reproductive data across maternal families within each FACE ring resulted in a total sample size of 24 replicates (from both growth chamber trials) for conductance and 12 replicates (from the first growth chamber trial) for inflorescence weight. Stomatal conductance data from both growth chamber trials were analysed with chamber effect as a random factor. Analyses of variance of both conductance and reproductive data were conducted using JMP v.10 software (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Although the number of maternal families in our experiment was relatively low, we initially planned to use family-level data to estimate broad-sense heritability for both conductance and inflorescence weight. However, an initial analysis of the data revealed that variability around estimated parameters was so large as to render the estimated values unreliable and so these data and analyses are not presented. To estimate rates of evolutionary change in conductance, we used formula found in Bone & Farres (2001) to calculate the rate of evolution in haldanes (change in mean per generation, in phenotypic standard deviation units) between FACE seed sources for populations from both growth chamber CO2 environments.

Results

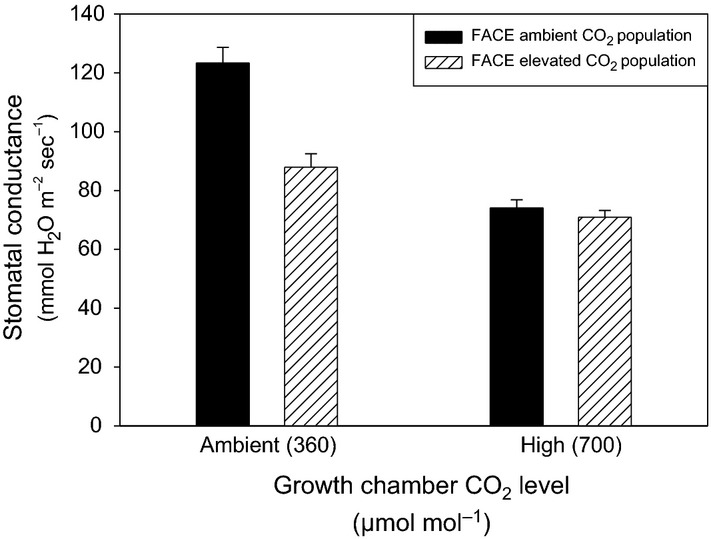

Under ambient (360 μmol mol−1) CO2 conditions in the growth chamber, Bromus plants from elevated CO2 field populations exhibited significantly lower stomatal conductance than ambient CO2 field populations (contrast F = 14.28, P = 0.0014; Fig. 1 and Table 1A). Under high-CO2 growth chamber conditions, the lack of a significant population source effect (contrast F = 0.01, P = 0.9132; Table 1A) suggests a pronounced reduction or canalisation of phenotypic differences in conductance between field populations (Fig. 1). Averaged across field source populations, plants grown in high-CO2 growth chambers exhibited significantly lower stomatal conductance than plants grown in ambient-CO2 growth chambers (F = 27.26, P < 0.0001; Table 1A). This main effect of growth chamber CO2 level indicates a phenotypically plastic reduction in conductance for both field source populations in response to higher CO2. The interaction between population source and growth chamber CO2 level was also significant (F = 6.79, P = 0.0179; Fig. 1 and Table 1A), suggesting that elevated CO2 field populations have a reduced capacity for phenotypically plastic conductance adjustments in response to lower levels of CO2. Chamber effects on conductance were not significant (F = 0.87, P = 0.3940; Table 1A). The rates of evolutionary divergence between FACE seed sources in the ambient- vs. high-CO2 growth chamber environments were −0.243 and −0.105 haldanes, respectively.

Figure 1.

Evolution of reduced plasticity in stomatal conductance. Genetic differences in plastic response are indicated by interactive effects of field population source and growth chamber CO2 level on stomatal conductance in Bromus (mean ± SE).

Table 1.

Analyses of variance for the two-way factorial design examining the main and interactive effects of FACE field population source and growth chamber CO2 levels on (A) stomatal conductance, (B) inflorescence weight, (C) concentration of leaf nitrogen (microgrammes of N per gramme of leaf) and (D) number of days from planting to first flower.

| Source | d.f. | Mean square | F ratio | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Stomatal conductance | ||||

| FACE population source | 1 | 1766.12 | 7.53 | 0.0134 |

| Growth chamber CO2 level | 1 | 6396.19 | 27.26 | <0.0001 |

| Population × CO2 level | 1 | 1593.12 | 6.79 | 0.0179 |

| Average maternal seed weight | 1 | 87.67 | 0.37 | 0.5486 |

| Chamber identity (random factor) | 1 | 1507.44 | 0.3940 | |

| Error | 18 | 234.61 | ||

| B. Inflorescence weight | ||||

| FACE population source | 1 | 0.6274 | 10.40 | 0.0145 |

| Growth chamber CO2 level | 1 | 0.7349 | 12.19 | 0.0101 |

| Population × CO2 level | 1 | 0.2925 | 4.85 | 0.0635 |

| Average maternal seed weight | 1 | 0.2012 | 3.34 | 0.1105 |

| Error | 7 | 0.0603 | ||

| C. Leaf [N] | ||||

| FACE population source | 1 | 0.0352 | 0.5319 | 0.4866 |

| Growth chamber CO2 level | 1 | 4.0420 | 61.1618 | <0.0001 |

| Population × CO2 level | 1 | 0.0415 | 0.6276 | 0.4511 |

| Error | 8 | 0.0661 | ||

| D. Days to first flower | ||||

| FACE population source | 1 | 3.485 | 0.0272 | 0.8732 |

| Growth chamber CO2 level | 1 | 94.454 | 0.7360 | 0.4159 |

| Population × CO2 level | 1 | 28.779 | 0.2242 | 0.6485 |

| Error | 8 | 128.340 | ||

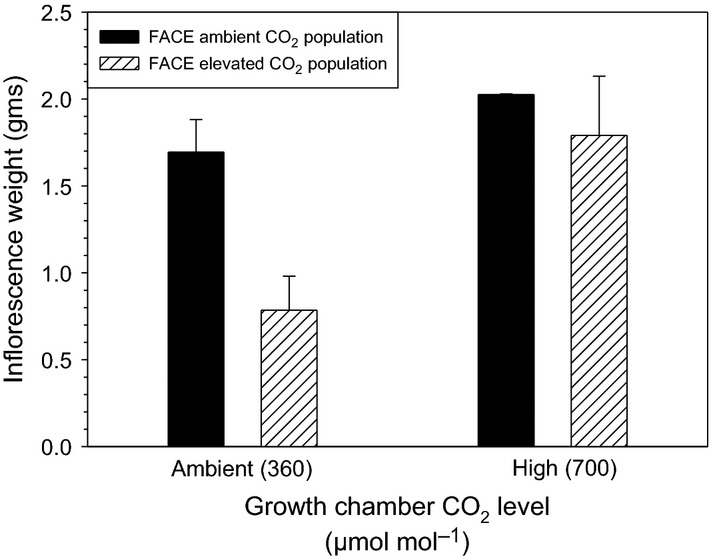

When grown in the ambient-CO2 growth chamber, Bromus plants descendent from elevated CO2 field populations produced significantly smaller inflorescences than ambient CO2 field populations (contrast F = 14.65, P = 0.0065; Table 1B and Fig. 2). Under high-CO2 growth chamber conditions, there was not a significant difference in reproduction between FACE field population sources (contrast F = 0.66, P = 0.44; Table 1B and Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Fitness consequences of CO2 level and population source. Interactive effects of genetic and growth chamber CO2 level on reproductive fitness in Bromus as measured by inflorescence weight (mean ± SE).

Leaf tissue quality as measured by leaf tissue nitrogen concentration (microgrammes of N per gramme of leaf) was affected by the growth chamber CO2 environment, but not by FACE seed source. There was no significant difference in leaf tissue nitrogen concentration between ambient versus elevated CO2 FACE seed sources (Table 1C), but leaf tissue nitrogen concentration was significantly greater in ambient- (4.2 ± 0.1 SE) vs. high (3.0 ± 0.1 SE)-CO2 growth chamber environments. There were no significant interactions between FACE seed sources and growth chamber CO2 levels for leaf tissue nitrogen concentrations. There were no significant differences in phenology between FACE seed sources or growth chamber CO2 levels, as measured by time to first flower in the first trial of the growth chamber common gardens (Table 1D).

Discussion

Physiological responses in Bromus to elevated CO2 treatments (i.e. changes in stomatal conductance) are consistent with an evolutionary response to FACE CO2 treatments in the field as well as a reduction in the capacity for phenotypic plasticity in conductance. We also detected a plastic reproductive fitness response to growth chamber CO2 treatments that differed between FACE CO2 populations. The FACE CO2 population source effect indicates that Bromus populations under elevated CO2 treatments evolved lower conductance in the field within a 7-year period. Because water was not limiting in the growth chambers, we could not experimentally test for the adaptive value of reduced conductance when water is in short supply. However, water is a primary limiting resource in this desert environment (Smith 1997) and a large body of literature on adaptation to xeric habitats suggests that this evolution of reduced conductance represents an adaptive response to conserve water and thus increase water-use efficiency (Bowes 1993; Tyree & Alexander 1993; Drake et al. 1997; Buckley & Schymanski 2014). Despite the low replication of CO2 treatments at the FACE site, the highly significant differences between FACE CO2 treatment populations suggest a robust evolutionary response in stomatal conductance. Our results indicating an evolutionary basis for reduced conductance under elevated atmospheric CO2 are consistent with research in several FACE experiments that demonstrated plastic decreases in stomatal conductance that resulted in increased water-use efficiency (Ainsworth & Long 2005).

A reduced capacity for conductance plasticity was found for the elevated CO2 FACE populations, suggesting that changes in conductance reaction norms may have occurred rapidly in these populations. It has been suggested that genetic assimilation may be more common than generally recognised, in part, because the process of genetic assimilation may occur relatively rapidly and thus escape detection (Pigliucci et al. 2006). We believe that this reduced capacity for plasticity in conductance likely represents selection on standing genetic variance in the norms of reaction associated with conductance plasticity that existed before elevated CO2 FACE treatments began. An examination of conductance plasticity differences among maternal families within the NDFF ambient control treatment provides evidence for the existence of this initial standing genetic variation in reaction norms. For example, two maternal families from separate populations (i.e. two different FACE rings) of the NDFF ambient control treatment exhibited conductance rates lower than the average for elevated sources when exposed to the ambient-CO2 growth chamber treatment. This suggests that genotypes with lower conductance and a reduced capacity for plastic response previously existed in the unselected populations. Empirical evidence from a long history of quantitative genetics (Roff 2007) as well as more recent theoretical developments (Barrett & Schluter 2007) indicate that adaptive responses based on standing genetic variation, rather than new mutations, are more likely to foster the type of rapid evolutionary change in conductance reaction norms that we observed in Bromus. In support of this idea, Case et al. (1998) reported differences among paternal families of wild radish in both the direction and magnitude of stomatal index responses to changing CO2; results suggesting that standing genetic variation in norms of reaction related to stomatal function exists in other weedy species.

A comparison of reproductive output between ambient and elevated CO2 FACE populations growing under ambient CO2 levels suggests a fitness cost associated with reduced capacity in these populations for plastic increases in conductance when CO2 is limiting (Fig. 2). Although we did not test for costs of plasticity directly, this reduction in conductance plasticity is at least consistent with the hypothesis that there are fitness costs associated with maintaining this plasticity when CO2 is less limiting (Pigliucci et al. 2006). Conversely, because the evolution of reduced conductance in the elevated CO2 populations is likely a selective response to conserve water and given that water was not limiting in the growth chambers, we did not expect to observe a fitness advantage associated with reduced conductance.

As an annual grass with little persistent seed bank development (Jurand et al. 2013), Bromus has a short generation time that may facilitate rapid evolutionary response to elevated atmospheric CO2. In contrast, long-lived perennial plants or annual plants with persistent seed banks (Templeton & Levin 1979) in this desert plant community have effectively longer generation times and thus may be expected to respond more slowly to selective pressures. In addition, variation in breeding systems among different plant species may significantly affect the likelihood of rapid evolutionary response. In particular, outcrossing can significantly increase gene flow that, in turn, reduces the effectiveness of local selection to evolve differences in adaptive traits. The highly selfing nature of Bromus may reduce gene flow among the FACE experimental rings and thus promote the local evolution of decreased stomatal conductance under elevated CO2.

Although we found evidence for rapid evolution in stomatal conductance in Bromus, information is lacking on whether other species in this desert environment have evolved physiological adaptations to rising atmospheric CO2. A field study at NDFF comparing growth, phenology and physiology between Bromus and a native short-lived perennial (Eriogonum inflatum Torr. & Frem.) indicated that E. inflatum exhibited a pronounced, season-long reduction in stomatal conductance under elevated CO2 (Huxman & Smith 2001). In fact, phenotypic reduction in conductance in E. inflatum plants exposed to elevated CO2 was stronger and more prolonged than in Bromus. Whether there is a genetic basis for reduced conductance in E. inflatum remains unknown, but the magnitude and extended duration of the response suggest that selection for reduced conductance in this native perennial might be strong under elevated CO2. If there is selection for reduced conductance in E. inflatum, this desert ephemeral species would be a prime candidate for testing whether this phenotypic response in conductance has a genetic basis. In contrast, a recent study by Newingham et al. (2014) on the response of the perennial plant community to elevated CO2 at the NDFF site suggests that evolutionary response in long-lived perennials may be unlikely. Despite a decade of exposure to elevated CO2, they found very little change in total cover in the woody and herbaceous perennial species examined. The authors suggest that slow growth and sporadic recruitment may constrain species responses at a community level; these growth and demographic characteristics might also reduce any evolutionary response within species.

Studies focused on potentially complex traits, such as plant morphology, growth and phenology have failed to detect significant evolutionary responses to elevated CO2 (Lau et al. 2007; Leakey & Lau 2012). It is possible that the genetic basis for variation in stomatal conductance may be simpler than the genetic structure underlying phenotypic variation in these more downstream traits. Recent genomic research in wheat indicates that multiple traits related to stomatal conductance and water-use efficiency may be controlled by relatively few genes and thus may respond fairly rapidly to selection (Panio et al. 2013). Similar research is not yet available for Bromus, but these results at least provide a possible genetic basis for more rapid evolutionary responses in physiological traits such as stomatal conductance. In general, differences among plant traits in the potential for evolutionary response are common and may reflect both environmental effects on the phenotypic expression of genetic variability (e.g. heritability) as well as genetic constraints (e.g. negative genetic correlations among traits) (Ackerly et al. 2000; Geber & Griffen 2003).

In addition, the natural field conditions within the FACE rings may have promoted an evolutionary response in conductance by providing a complex environment, whereby the effects of elevated CO2 on interspecific interactions might alter both phenotypic expression of genetic variation and the efficacy of the selection in causing evolutionary change (Lau et al. 2014). The effects of competition on evolutionary responses in Bromus at NDFF remain unknown. However, research on potential responses of a winter annual community in the Sonoran Desert to environmental variation and climate change suggest that interspecific interactions and temporal variability in rainfall may act to maintain trade-offs between water-use efficiency and relative growth rate (Huxman et al. 2013). This research focused on among-species differences, but it is not unreasonable to suggest that these interactions between biotic and abiotic stressors might also influence the capacity of selection to alter within-species variation in traits associated with water-use efficiency (e.g. stomatal conductance). At an ecosystem level, the effects of elevated CO2 on conductance, assimilation and water-use efficiency can be especially important within a desert environment. Within xeric communities, changes in conductance can influence a number of ecosystem properties ranging from increased soil water to evapotranspiration dynamics (Morgan et al. 2004).

A logistic factor that may contribute to a general lack of evidence for evolutionary responses to elevated CO2 is that the level of replication of CO2 treatments at a FACE site is typically low. It is possible that concerns over low statistical power at FACE sites have discouraged exploration of evolutionary response to elevated CO2 especially if the initial assumption is that evolutionary responses will be weak (i.e. small treatment effect sizes). Our results indicate that the magnitude of effects associated with evolutionary response to elevated CO2 can be substantial and so further research focused on detecting genetic shifts might reveal that rapid evolutionary responses to FACE treatments are more common than currently supposed.

Our findings corroborate previous research (Huxman et al. 1998; Long et al. 2004; Ainsworth & Long 2005) that plants respond phenotypically to elevated CO2 by expressing reduced tissue quality (i.e. nitrogen concentration) and thus an increased carbon-to-nitrogen (C:N) ratio of leaf tissue. If NO3 is the primary source of nitrogen, as it was in our study, then a reduction in leaf nitrogen may reflect a reduced capacity for NO3 uptake under elevated CO2 because of a reduction in photorespiration (Bloom et al. 2012). Reduced tissue quality may negatively impact Bromus populations in particular because of an associated reduction in seed quality and seedling vigour (Huxman et al. 1998, 2001). Compared to seeds produced under ambient CO2, seeds from Bromus plants grown under elevated (700 μmol mol−1) CO2 had higher C:N ratios and reduced seed reserves. Upon germination, seedlings from Bromus plants grown under elevated CO2 also grew more slowly and produced fewer leaves (Huxman et al. 1998). As noted by Huxman et al. (1998), this reduction in seed quality and seedling vigour could have a substantial impact on the future demographic dynamics and invasive success of Bromus as atmospheric CO2 increases. Thus, there may be a significant fitness trade-off in that higher seed production under elevated CO2 may be offset by a reduction in seedling survival and vigour that, in turn, might constrain Bromus population growth and invasive spread.

Rates of evolutionary divergence in stomatal conductance between FACE seed sources grown in the ambient- vs. high-CO2 growth chamber environments (−0.243 and −0.105 haldanes, respectively) are near the high end of the studies reviewed by Bone & Farres (2001). These relatively high rates of evolutionary change in stomatal conductance support their suggestion that physiological traits may evolve more rapidly than morphological traits. Although the same FACE populations were used in high- and ambient-CO2 growth chambers, estimates of evolutionary rates were much higher in the ambient-CO2 growth environment. This environmental effect on the phenotypic expression of evolutionary change lends support to the observation that estimates of many evolutionary parameters, including local adaptation and heritability, may vary with environmental conditions (Williams et al. 2008).

Evolutionary responses in this invasive species to rising CO2 could have broad ecosystem impacts because of its effect on fire regimes. As Bromus populations spread throughout the Mojave Desert ecosystem, they provide a continuous fine fuel source that increases the frequency and size of fires. This change in fire regime, in turn, threatens native plant ecosystems that are not adapted to frequent, widespread fires (Smith et al. 2000). Previous investigators have suggested that the long-term success and dominance of Bromus in this arid ecosystem will be promoted by phenotypically plastic increases in biomass and seed production in response to elevated CO2 (Smith et al. 2000). Our evidence for contemporary in situ evolution of Bromus populations suggests that genetic shifts in response to elevated CO2 may also promote the persistence and dominance of this desert weed in the Mojave Desert ecosystem. In general, the current wave of biological invasions may be due, in part, to the ability of non-native species to evolve rapidly in response to human-induced environmental change (Lee 2002; Rice & Emery 2003).

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff and researchers at the NDFF for logistic support and J. Richards, R. Karban, J. Chase, J. Gurevitch and three anonymous referees for comments on previous versions of the manuscript. This research was supported by NSF grant DGE-0801430 to J.G. and NSF grant DGE-0114432 to K.R. Operation of the Nevada Desert FACE Facility was supported by the US Department of Energy (DE-FC002-91ER5667), Brookhaven National Laboratory, the US Department of Energy National Nuclear Security Administration/Nevada Operations Office and Bechtel Nevada.

Authorship

J.G. and K.R. designed experiment, J.G. collected the data and J.G. and K.R. analysed the data. J.G. wrote the first draft of the manuscript and both authors contributed substantially to revisions.

References

- Ackerly DD, Dudley SA, Sultan SE, Schmitt J, Coleman JS, Linder CR, et al. The evolution of plant ecophysiological traits: recent advances and future directions. Bioscience. 2000;50:979–995. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth EA. Long SP. What have we learned from 15 years of free-air CO2 enrichment (FACE)? A meta-analytic review of the responses of photosynthesis, canopy properties and plant production to rising CO2. New Phytol. 2005;165:351–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett RDH. Schluter D. Adaptation from standing genetic variation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2007;23:38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom AJ, Asensio JSR, Randall L, Rachmilevitch S, Cousins AB. Carlisle EA. CO2 enrichment inhibits shoot nitrate assimilation in C3 but not C4 plants and slows growth under nitrate in C3 plants. Ecology. 2012;93:355–367. doi: 10.1890/11-0485.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bone E. Farres A. Trends and rates of microevolution in plants. Genetica. 2001;112:165–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowes G. Facing the inevitable: plants and increasing atmospheric CO2. Ann. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 1993;44:309–332. [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw AD. McNeilly T. Evolutionary response to global climatic change. Ann. Bot. (London) 1991;67:5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley TN. Schymanski SJ. Stomatal optimisation in relation to atmospheric CO2. New Phytol. 2014;201:372–377. doi: 10.1111/nph.12552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case AL, Curtis PS. Snow AA. Heritable variation in stomatal responses to elevated CO2 in wild radish, Raphanus raphanistrum (Brassicaceae) Am. J. Bot. 1998;85:253–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins S. Bell G. Phenotypic consequences of 1,000 generations of selection at elevated CO2 in a green alga. Nature. 2004;431:566–569. doi: 10.1038/nature02945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake BG, Gonzàlez-Meler MA. Long SP. More efficient plants: a consequence of rising atmospheric CO2Ann. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 1997;48:609–639. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.48.1.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franks SJ, Sims S. Weis AE. Rapid evolution of flowering time by an annual plant in response to a climate fluctuation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:1278–1282. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608379104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franks PJ, Adams MA, Amthor JS, Barbour MM, Berry JA, Ellsworth DS, et al. Sensitivity of plants to changing atmospheric CO2 concentration: from the geological past to the next century. New Phytol. 2013;197:1077–1094. doi: 10.1111/nph.12104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenck G, van der Linden L, Mikkelsen TN, Brix H. Jørgensen RB. Response to multi-generational selection under elevated [CO2] in two temperature regimes suggests enhanced carbon assimilation and increased reproductive output in Brassica napus L. Ecol. Evol. 2013;3:1163–1172. doi: 10.1002/ece3.523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geber MA. Griffen LR. Inheritance and natural selection on functional traits. Int. J. Plant Sci. 2003;164:S21–S42. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter R. Bromus invasions on the Nevada test site - present status of B. rubens and B. tectorum with notes on their relationship to disturbance and altitude. Great Basin Nat. 1991;51:176–182. [Google Scholar]

- Huxman TE. Smith SD. Photosynthesis in an invasive grass and native forb at elevated CO2 during an El Niño year in the Mojave Desert. Oecologia. 2001;128:193–201. doi: 10.1007/s004420100658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxman TE, Hamerlynck EP, Jordan DN, Salsman KJ. Smith SD. The effects of parental CO2 environment on seed quality and subsequent seedling performance in Bromus rubens. Oecologia. 1998;114:202–208. doi: 10.1007/s004420050437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxman TE, Hamerlynck EP. Smith SD. Reproductive allocation and seed production in Bromus madritensis ssp rubens at elevated atmospheric CO2. Funct. Ecol. 1999;13:769–777. [Google Scholar]

- Huxman TE, Charlet TN, Grant C. Smith SD. The effects of parental CO2 and offspring nutrient environment on initial growth and photosynthesis in an annual grass. Int. J. Plant Sci. 2001;162:617–623. [Google Scholar]

- Huxman TE, Kimball S, Angert AL, Gremer JR, Barrongafford GA. Venable DL. Understanding past, contemporary, and future dynamics of plants, populations, and communities using Sonoran Desert winter annual plants. Am. J. Bot. 2013;100:1369–1380. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1200463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. In: Stocker TF,, Qin D, Plattner G-K, Tignor M, Allen SK, Boschung J, Nauels A, editors; Xia Y, Bex V, Midgley PM, editors. 2013. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Cambridge Cambridge University Press, 1535. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan DN, Zitzer SF, Hendrey GR, Lewin KF, Nagy J, Nowak RS, et al. Biotic, abiotic and performance aspects of the Nevada Desert Free-Air CO2 Enrichment (FACE) Facility. Global Change Biol. 1999;5:659–668. [Google Scholar]

- Jurand BS, Abella SR. Suazo AA. Soil seed bank longevity of the exotic annual grass Bromus rubens in the Mojave Desert, USA. J. Arid Environ. 2013;94:68–75. [Google Scholar]

- Kingsolver JG. Physiological sensitivity and evolutionary responses to climate change. In: Körner C, Bazzaz FA, editors. Carbon Dioxide, Populations, and Communities. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1996. pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Lau JA, Shaw RG, Reich PB, Shaw FH. Tiffin P. Strong ecological but weak evolutionary effects of elevated CO2 on a recombinant inbred population of Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 2007;175:351–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau JA, Shaw RG, Reich PB. Tiffin P. Indirect effects drive evolutionary responses to global change. New Phytol. 2014;201:335–343. doi: 10.1111/nph.12490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leakey ADB. Lau JA. Evolutionary context for understanding and manipulating plant responses to past, present and future atmospheric [CO2] Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. 2012;367:613–629. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CE. Evolutionary genetics of invasive species. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2002;17:386–391. [Google Scholar]

- Long SP, Ainsworth EA, Rogers A. Ort DR. Rising atmospheric carbon dioxide: plants face the future. Ann. Rev. Plant Biol. 2004;55:591–628. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan JA, Pataki DE, Körner C, Clark H, Del Grosso SJ, Grünzweig JM, et al. Water relations in grassland and desert ecosystems exposed to elevated atmospheric CO. Oecologia. 2004;140:11–25. doi: 10.1007/s00442-004-1550-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newingham BA, Vanier CH, Kelly LJ, Charlet TN. Smith SD. Does a decade of elevated [CO2] affect a desert perennial plant community? New Phytol. 2014;201:498–504. doi: 10.1111/nph.12546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panio G, Motzo R, Mastrangelo AM, Marone D, Cattivelli L, Giunta F, et al. Molecular mapping of stomatal-conductance-related traits in durum wheat (Triticum turgidum ssp. durum. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2013;162:258–270. [Google Scholar]

- Pigliucci M, Murren CJ. Schlichting CD. Phenotypic plasticity and evolution by genetic assimilation. J. Exp. Biol. 2006;209:2362–2367. doi: 10.1242/jeb.02070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice KJ. Emery NC. Managing microevolution: restoration in the face of global change. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2003;1:469–478. [Google Scholar]

- Roff DA. Evolutionary Quantitative Genetics. New York, NY: Chapman & Hall; 2007. p. 494. [Google Scholar]

- Sakai AK, Allendorf FW, Holt JS, Lodge DM, Molofsky J, With KA, et al. The population biology of invasive species. Ann. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 2001;32:305–332. [Google Scholar]

- Scheiner SM. Genetics and evolution of phenotypic plasticity. Ann. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1993;24:35–68. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid B, Birrer A. Lavigne C. Genetic variation in the response of plant populations to elevated CO2 in a nutrient-poor, calcareous grassland. In: Körner C, Bazzaz FA, editors; Carbon Dioxide, Populations, and Communities. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1996. pp. 31–50. [Google Scholar]

- Smith SD, et al. Physiological Ecology of North American Desert Plants. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1997. p. 286. [Google Scholar]

- Smith SD, Huxman TE, Zitzer SF, Charlet TN, Housman DC, Coleman JS, et al. Elevated CO2 increases productivity and invasive species success in an arid ecosystem. Nature. 2000;408:79–82. doi: 10.1038/35040544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Templeton AR. Levin DA. Evolutionary consequences of seed pools. Am. Nat. 1979;114:232–249. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas SC. Jasienski M. Genetic variability and the nature of microevolutionary responses to elevated CO2. In: Körner C, Bazzaz FA, editors; Carbon Dioxide, Populations, and Communities. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1996. pp. 51–81. [Google Scholar]

- Tousignant D. Potvin C. Selective responses to global change: experimental results on Brassica juncea (L.) Czern. In: Bazzaz FA, editor; Körner C, editor. Carbon Dioxide, Populations, and Communities. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1996. pp. 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Tyree MT. Alexander JD. Plant water relations and the effects of elevated CO2: a review and suggestions for future research. Vegetatio. 1993;104:47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Waddington CH. Genetic assimilation. Adv. Genet. 1961;10:257–290. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2660(08)60119-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward JK, Antonovics J, Thomas RB. Strain BR. Is atmospheric CO2 a selective agent on model C-3 annuals? Oecologia. 2000;123:330–341. doi: 10.1007/s004420051019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieneke S, Prati D, Brandl R, Stocklin J. Auge H. Genetic variation in Sanguisorba minor after 6 years in situ selection under elevated CO2. Global Change Biol. 2004;10:1389–1401. [Google Scholar]

- Williams JL, Auge H. Maron JL. Different gardens, different results: native and introduced populations exhibit contrasting phenotypes across common gardens. Oecologia. 2008;157:239–248. doi: 10.1007/s00442-008-1075-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]