Abstract

Objectives

We have previously shown that peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ), a transcription factor, is essential for the normal growth and development of cartilage. In the present study, we created inducible cartilage-specific PPARγ knockout (KO) mice and subjected these mice to the destabilisation of medial meniscus (DMM) model of osteoarthritis (OA) to elucidate the specific in vivo role of PPARγ in OA pathophysiology. We further investigated the downstream PPARγ signalling pathway responsible for maintaining cartilage homeostasis.

Methods

Inducible cartilage-specific PPARγ KO mice were generated and subjected to DMM model of OA. We also created inducible cartilage-specific PPARγ/mammalian target for rapamycin (mTOR) double KO mice to dissect the PPARγ signalling pathway in OA.

Results

Compared with control mice, PPARγ KO mice exhibit accelerated OA phenotype with increased cartilage degradation, chondrocyte apoptosis, and the overproduction of OA inflammatory/catabolic factors associated with the increased expression of mTOR and the suppression of key autophagy markers. In vitro rescue experiments using PPARγ expression vector reduced mTOR expression, increased expression of autophagy markers and reduced the expression of OA inflammatory/catabolic factors, thus reversing the phenotype of PPARγ KO mice chondrocytes. To dissect the in vivo role of mTOR pathway in PPARγ signalling, we created and subjected PPARγ-mTOR double KO mice to the OA model to see if the genetic deletion of mTOR in PPARγ KO mice (double KO) can rescue the accelerated OA phenotype observed in PPARγ KO mice. Indeed, PPARγ-mTOR double KO mice exhibit significant protection/reversal from OA phenotype.

Significance

PPARγ maintains articular cartilage homeostasis, in part, by regulating mTOR pathway.

Keywords: Osteoarthritis, Chondrocytes, Arthritis

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is among the most prevalent chronic human health disorders, and the most common form of arthritis. Typical characteristics of OA include cartilage deterioration/damage, inflammation, synovial fibrosis, subchondral bone remodelling and osteophyte formation.1–4 Chondrocytes are essential for maintaining homeostasis as well as integrity of the extracellular matrix (ECM) within the articular cartilage. We are now beginning to understand the mechanisms leading to altered cartilage homeostasis, accelerated chondrocyte cell death and subsequent cartilage degeneration during OA. We and others have recently reported that the process of autophagy, a form of programmed cell survival,5 is dysregulated during OA and may contribute to the decreased chondroprotection and degradation of the articular cartilage.6–10 Carames et al.9 showed that autophagy is a protective mechanism in normal cartilage, and its aging-related loss is associated with cell death and OA. We have also shown that during OA, excessive mammalian target for rapamycin (mTOR) (major negative regulator of autophagy) signalling and the subsequent suppression of autophagy may contribute to cartilage degradation.6 The genetic deficiency of mTOR and treatment with rapamycin (mTOR inhibitor) has been shown to reduce the severity of experimental OA.6 10 However, endogenous mediators that control mTOR signalling and ultimately chondrocyte cell death/survival mechanisms in the articular cartilage are unknown. Identifying such endogenous factors that control mTOR signalling and articular cartilage homeostasis could lead to several promising therapeutic strategies in OA.

PPARγ is a ligand-activated transcription factor originally identified to play a key role in lipid homeostasis. We and others have shown that PPARγ possesses potent anti-inflammatory, anticatabolic and antifibrotic properties, and is a potential therapeutic target for OA disease.11–18 Since global PPARγ knockout (KO) mice are not viable,19 and cartilage-specific PPARγ germ-line KO mice exhibit serious growth and developmental defects,13 14 we created inducible PPARγ KO mice using Col2-rTACre-doxycycline system to bypass the early developmental defects and to specifically elucidate the in vivo role of PPARγ in OA pathophysiology. This study first explored the role of PPARγ in chondro-protection by determining the effect of PPARγ deletion on mTOR and autophagy signalling pathway and its subsequent effect on the kinetics of OA progression and severity using mice models of OA. In addition to cartilage-specific PPARγ KO mice, we also generated inducible cartilage-specific PPARγ-mTOR double KO mice to specifically dissect the in vivo role of mTOR pathway in PPARγ signalling during OA. This study is the first to show that PPARγ is involved in maintaining articular cartilage homeostasis, in part, through the modulation of mTOR signalling pathway.

Methods

Generation of inducible cartilage-specific PPARγ KO mice

Inducible cartilage-specific PPARγ KO mice were generated by mating mice containing a PPARγ gene flanked by LoxP sites (C57BL/6-PPARγfl/fl, Jackson Laboratory) with C57BL/6 Col2-rt-TA-Cre transgenic mice20 (obtained from Dr Peter Roughley, McGill University, Montreal, Canada) as we have previously reported.6 Six-week old PPARγfl/fl Cre mice were fed doxycycline (Sigma) dissolved at 10 µg/mL in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4, by oral gavage with the dose of 80 µL/g body weight for 7 days. rtTA requires interaction with doxycycline (Sigma–Aldrich, Oakville, Ontario, Canada) to permit interaction with the TetO sequence to drive Cre expression resulting in the inactivation of PPARγ floxed alleles to generate a cartilage-specific PPARγ KO mice. PPARγfl/fl Cre mice without doxycycline (saline) treatment were used as control mice. The routine genotyping of ear punch DNA followed by the confirmation of loss of PPARγ expression in chondrocytes by reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR), western blotting and immunohistochemistry was performed. All animal procedures and protocols were approved by the Comité Institutionnel de protection des animaux (Institutional Animal Protection Committee) of the University of Montreal Hospital Research Centre (CRCHUM).

Surgically induced OA mouse model

Control mice and PPARγ KO mice were subjected to surgically induced OA by the destabilisation of the medial meniscus (DMM model) in the right knee of 10-week-old animals as we have previously described.6 21 Briefly, after anaesthesia with isoflurance in O2, the cranial attachment of the medial meniscus to the tibial plateau (menisco-tibial ligament) of the right knee was transected. A sham operation, consisting of an arthrotomy without the transaction of the cranial menisco-tibial ligament, was also performed in the right knee joint of separate control and PPARγ KO mice.

Histology

Freshly dissected mouse knee joints were fixed overnight in TissuFix (Chaptec, Montreal, Quebec, Canada), decalcified for 1.5 h in RDO Rapid Decalcifier (Apex Engineering, Plainfield, Illinois, USA), further fixed in TissuFix overnight, followed by embedding in paraffin and sectioning. Sections (5 µm) were deparaffinised in xylene followed by a graded series of alcohol washes. Sections were stained with Safranin-O/Fast Green (Sigma–Aldrich, Oakville, Ontario, Canada) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Slides were evaluated by two independent readers in a blinded fashion. To determine the extent of cartilage degeneration, histological scoring method issued by Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) was used for analysis as previously described.6 22

Immunohistochemistry and TUNEL staining

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) studies were performed using specific antibodies for target genes. For IHC analysis, Dakocytomation (Dako)-labelled streptavidin biotin+System horseradish peroxidase kit was used following the manufacturer's recommended protocol as previously described.14 Five micrometer sections were deparaffinised in xylene followed by a graded series of alcohol washes. Endogenous peroxide was blocked for 5 min using 3% H2O2. Non-specific IgG binding was blocked by incubating sections with bovine serum albumin (BSA) (0.1%) in PBS for 1 h. Sections were then incubated with primary antibody in a humidified chamber and left overnight at 4°C. Next, sections were incubated with biotinylated link for 30 min followed by streptavidin for 1 h. The diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride chromogen substrate solution was then added until sufficient colour developed. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) dUTP Nick-End Labeling (TUNEL) assay was performed using ApopTag Plus Peroxidase In Situ Apoptosis Detection Kit according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (Millipore, Ontario, Canada). The quantification of number of positive cells for each antigen was performed by the determination of the total number of chondrocytes and the total number that stained positive for the antigen. The final results were expressed as the percentage of positive cells for the antigen.

Chondrocyte primary cell culture

The microdissection of mouse knee articular cartilage (medial and lateral femoral condyle and tibial plateau) was performed under a surgical microscope (Motic SMZ-168; Fisher Scientific Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada) to carefully dissect only articular cartilage and avoid subchondral bone. Primary chondrocytes were prepared from the dissected articular cartilage by enzymatic digestion as previously described.6 13 Briefly, dissected articular cartilage was rinsed in PBS, and incubated at 37°C for 15 min in trypsin-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid followed by digestion with 2 mg/mL collagenase at 37°C for 2 h in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin under an atmosphere of 5% CO2. The cell suspension was filtered through a 70 -µm cell strainer (Falcon, Fort Worth, Texas, USA), washed, counted and plated with DMEM containing 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin under an atmosphere of 5% CO2. At confluence, the cells were detached and plated at a density of 2×105 cells/well in six-well plates for experiments. Only first-passage cells were used for the experiments.

Transfection

Transient transfection experiments were performed using the Transfectine TMLipid Reagent according to the manufacturer's recommended protocol (Biorad, Mississauga, Canada). Briefly, chondrocytes were seeded 24 h prior to transfection at a density of 2×105 cells/well in six-well plates, and transiently transfected with 1 µg of the PPARγ expression vector, or control plasmid (pcDNA empty vector) in the presence of transfectin. After 5 h, the medium was changed with DMEM containing 1% fetal calf serum, and samples were incubated at 37°C in an incubator containing 5% CO2 for 48 h. PPARγ expression and pcDNA empty vectors were donated by Dr R Evans (The Salk Institute, San Diego, California, USA). Cells were then harvested for RNA and protein extractions as previously described.13

RNA isolation and real-time PCR

Primary chondrocytes were prepared from the dissected articular cartilage and cultured as discussed above. Total RNA was isolated from the chondrocytes using Trizol (Invitrogen, Burlington, Ontario, Canada). RNeasy Mini kit (QIAGEN, Toronto, Ontario, Canada) was used, including on-column DNase digestion to eliminate DNA (RNase-Free DNase Set, QIAGEN). RNA were reverse transcribed and amplified using the QuantiTect Reverse Transcription PCR Kit (QIAGEN) on the Rotor Gene 3000 real-time PCR system (Corbett Research, Mortlake, Australia) according to the manufacturer’s protocol as shown before.6 Fold increase in PCR products was analysed using a 2−ΔΔCt method. All experiments were performed in duplicate for each sample, and the primers were designed using Primer3 online software. Data were normalised to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) messenger RNA (mRNA) levels and represent averages and SEM. The statistical significance of quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) results was determined by a two-way analysis of variance with the Bonferroni post-test, using GraphPad Prism V.3.00 for Windows.

Western blotting

Cells were lysed in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS), and the protein content of the lysates was determined using bicinchoninic acid protein assay reagent (Pierce Rockford) with BSA as the standard. Cell lysates were adjusted to identical equals of protein and then were applied to SDS-polyacrylamide gels (10%–15%) for electrophoresis. Next, the proteins were electroblotted onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. After the membranes were blocked in 10 mM Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween-20 (TBS-T) and 5% skimmed milk, the membranes were probed for 1.5 h with the respective antibodies in TBS-T. After washing the membranes with TBS-T, the membranes were incubated overnight with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antirabbit, or horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antimouse IgG (1:10 000 dilution in TBS-T containing 5% skimmed milk) at 4°C. Subsequently, by further washing with TBS-T, protein bands were visualised with an enhanced chemiluminescence system using a Bio-Rad Chemidoc Apparatus.

Generation of inducible cartilage-specific PPARγ-mTOR double KO mice

The generation of inducible cartilage-specific PPARγ-mTOR double KO mice was performed by using the Cre-Lox methodology. First, mTORfl/flCol2-rt-TA-Cre mice were generated by mating mice containing an mTOR gene flanked by LoxP sites (C57BL/6-mTORfl/fl, Jackson Laboratory) with C57BL/6 Col2-rt-TA-Cre transgenic mice as previously reported.6 Subsequently, PPARγfl/flCol2-rt-TA-Cre mice were crossed with mTORfl/flCol2-rt-TA-Cre to create PPARγfl/fl-mTORfl/flCol2-rtTA-Cre animals. Next, 6-week-old PPARγfl/fl-mTORfl/flCol2-rtTA-Cre mice were fed doxycycline (sigma-) dissolved at 10 µg/mL in PBS by oral gavage with the dose of 80 µL/g body weight for 7 days. The routine genotyping of ear punch DNA followed by the confirmation of loss of PPARγ and mTOR expression in the chondrocytes by RT-PCR, and western blotting was performed.6 13 20 All animal procedures were approved by the Comité Institutionnel de protection des animaux (Institutional Animal Protection Committee) of the University of Montreal Hospital Research Centre (CRCHUM). PPARγfl/fl-mTORfl/fl-Col2-rtTA-Cre treated with doxycycline are refereed as PPARγ-mTOR double KO mice, whereas PPARγfl/fl-mTORfl/flCol2-rtTA-Cre treated with saline (control) are referred as control mice. Mice, 10 weeks old, were subjected to DMM OA surgery and were sacrificed at 10 weeks postsurgery for histo-morphometric evaluation and biochemical analyses.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis, unless stated otherwise, was performed using the two-tailed Student's t test; p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

PPARγ KO mice exhibit accelerated OA phenotype

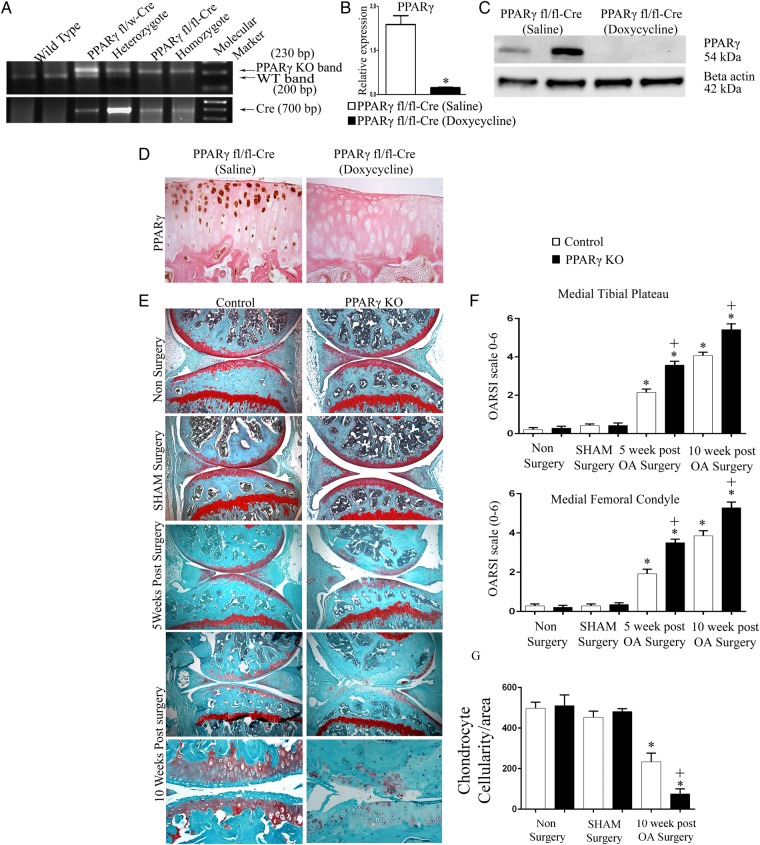

To determine the specific in vivo role of PPARγ in OA pathophysiology, we first generated inducible cartilage-specific PPARγ KO mice. The presence of Cre transgene in PPARγfl/fl mice was confirmed by genotyping (figure 1A). PPARγfl/fl Cre mice that were 6 weeks old were fed doxycycline (or saline for controls) for 1 week by oral gavage, and the loss of PPARγ expression in articular chondrocytes was confirmed by qPCR, western blotting and immunohistochemistry in 10-week-old mice (figure 1B–D). Doxycycline-treated PPARγfl/flCol2-rtTA-Cre mice are referred to as PPARγ KO mice, and saline-treated PPARγfl/flCol2-rtTA-Cre mice are referred as control mice throughout the manuscript. The assessment of weight, size, as well as histological analysis of articular cartilage at 10 weeks and 6 months (see online supplementary figure S1) postbirth, showed no significant phenotypic differences between control and inducible cartilage-specific PPARγ KO mice. We then subjected 10-week-old male control and PPARγ KO mice to a DMM model of OA, or sham surgery, and determined the kinetics of OA at 5 and 10 weeks post-OA surgery. As expected, histological analysis at 5 weeks post-OA surgery, control mice knee joints showed some loss of proteoglycans (loss of safranin O staining), roughening of the articular cartilage, and some loss of articular chondrocyte cellularity (figure 1E). However, PPARγ KO mice showed greater loss of proteoglycans, the loss of cellularity and destruction in some regions of the articular cartilage at 5 weeks post-OA surgery. This phenotype became more profound at 10 weeks post-OA surgery, where PPARγ KO mice, in comparison with control mice, showed significant and severe destruction of the articular cartilage (in both medial tibial plateau and medial femoral condyle) associated with greater loss of proteoglycans and chondrocyte cellularity. These results were confirmed by the significant increase in the OARSI scores (figure 1F) and significant loss of articular chondrocytes (figure 1G) in PPARγ KO mice compared with control mice post-OA surgery (figure 1F).

Figure 1.

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) knockout (KO) mice exhibit accelerated osteoarthritis (OA) phenotype: (A) genotyping confirmed the presence of the Cre transgene in heterozygote (PPARγfl/w) and homozygote (PPARγfl/fl) mice and its absence in wild-type mice; (B and C) qPCR and western blotting analysis of isolated chondrocytes confirmed absence of PPARγ expression in PPARγfl/flCre mice treated with doxycycline compared with PPARγfl/flCre mice treated with saline. (n=5, *p<0.05); (D) immunohistochemical staining for PPARγ confirmed the absence of PPARγ expression in the articular cartilage of PPARγfl/flCre mice treated with doxycycline compared with PPARγfl/flCre mice treated with saline (n=4, magnification: ×40); (E) histological analysis using Safranin O/fast green staining of 5 and 10 weeks post-OA surgery knee joint sections demonstrate that PPARγ KO mice exhibit accelerated osteoarthritis (OA) phenotype associated with greater cartilage degradation and loss of safranin O staining compared with control mice (magnification: ×6.2 and ×25); (F) Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) scoring of medial tibial plateau and medial femoral condyle showed a significant increase (*p<0.05) in the OARSI scores in both control OA and PPARγ KO OA mice (5 weeks and 10 weeks post-OA surgery) compared with non-surgery and sham surgery control and PPARγ KO mice, respectively. A significant increase (+p<0.05) in the OARSI scores was observed in both 5 and 10 weeks post-OA surgery PPARγ KO mice compared with 5 and 10 weeks post-OA surgery control mice (n=6); (G) quantification of articular chondrocyte cellularity revealed significant (*p<0.05) loss of chondrocyte cellularity in both control OA and PPARγ KO OA mice (10 weeks post-OA surgery) compared with non-surgery and sham surgery control and PPARγ KO mice, respectively. PPARγ KO mice at 10 weeks post-OA surgery exhibited significantly (+p<0.05) greater loss of chondrocyte cellularity compared with control mice at 10 weeks post-OA surgery. (n=4).

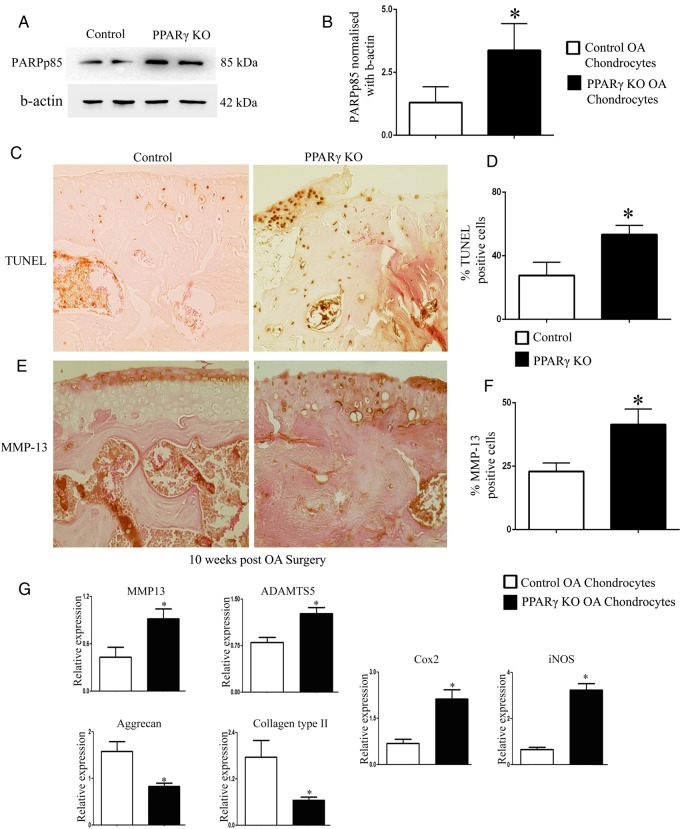

PPARγ KO mice exhibit enhanced cell death, increased expression of catabolic/inflammatory markers, and decreased expression of anabolic markers

Since we observed decreased articular chondrocyte cellularity in PPARγ KO OA mice compared with control OA mice, we isolated chondrocytes from PPARγ KO and control mice at 5 weeks post-OA surgery, and determined the expression of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) p85 by western blotting to account for cell apoptosis. Results showed increased expression of PARPp85 in PPARγ KO OA chondrocytes compared with control OA chondrocytes (figure 2A, B). TUNEL assay further confirmed enhanced cell death (increased percentage of TUNEL-positive cells) in PPARγ KO mice compared with control mice at 10 weeks post-OA surgery (figure 2C, D).

Figure 2.

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) knockout osteoarthritis (KO OA) mice exhibit enhanced cell death, increased expression of catabolic/inflammatory markers and decreased expression of anabolic markers: (A and B) western blotting analysis on isolated chondrocytes showed a significant increase in poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase p85 expression in PPARγ KO OA mice chondrocytes compared with control OA mice chondrocytes at 5 weeks post-surgery (n=4; p<0.05); (C–F) TUNEL staining and MMP-13 immunohistochemical analysis showed a significant increase in the percentage (%) of TUNEL and MMP-13 positive cells in PPARγ KO OA mice compared with control OA mice at 10 weeks post-OA surgery (n=4, magnification: ×40); (G) qPCR analysis showed a significant increase in the gene expression of MMP-13, ADAMTS-5, iNOS, and COX-2, and a significant decrease in the expression of collagen type II and aggrecan in PPARγ KO OA mice chondrocytes compared with control OA mice chondrocytes at 5 weeks post-OA surgery (n=4, *p<0.05).

Since matrix metalloproteinases (MMP)-13 is one of the major catabolic factors implicated in OA, we determined the expression of MMP-13 by IHC. Our results showed an increase in the percentage of MMP-13-positive cells in PPARγ KO mice compared with control mice at 10 weeks post-OA surgery (figure 2E, F). Further, qPCR analysis on isolated chondrocytes from PPARγ KO OA mice and control OA mice showed the enhanced gene expression of MMP-13, ADAMTS-5 (another key catabolic factor implicated in OA), enhanced expression of inflammatory-inducible enzymes including cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), and the decreased expression of collagen type II and aggrecan (two major anabolic components of the ECM of the articular cartilage) in PPARγ KO mice OA chondrocytes compared with control OA mice chondrocytes (figure 2G). These results show that PPARγ KO mice subjected to OA surgery exhibit accelerated chondrocyte loss and enhanced catabolic activity in the articular cartilage.

PPARγ deficiency results in aberrant mTOR and autophagy signalling

We have previously shown that during OA, excessive mTOR (major negative regulator of autophagy) signalling and the subsequent suppression of autophagy genes may contribute to decreased chondroprotection and cartilage degeneration.6 Further, treatment with rapamycin has been shown to reduce the severity of experimental OA.10

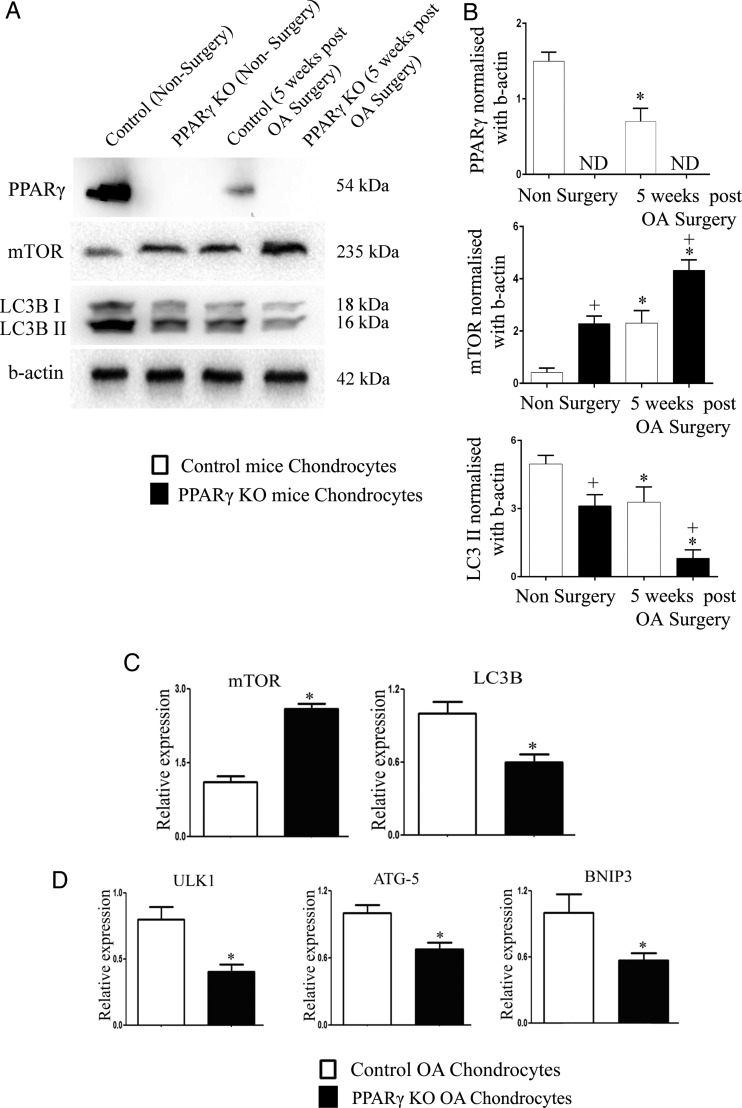

In the present study, we observed that PPARγ KO mice subjected to OA surgery exhibit accelerated chondrocyte cell death and enhanced catabolic activity. We therefore determined the effect of PPARγ deficiency on the expression of mTOR and autophagy markers in articular chondrocytes isolated from non-surgery and 5 weeks post-OA surgery control and PPARγ KO mice. As expected,17 our results first showed that PPARγ expression is significantly reduced in control OA surgery chondrocytes compared with control non-surgery chondrocytes (figure 3A, B). PPARγ expression was not detected in the PPARγ KO chondrocytes. The assessment of mTOR expression showed opposite expression profile compared with PPARγ expression profile. Low levels of mTOR expression were observed in control non-surgery chondrocytes, but were significantly elevated in control OA chondrocytes as expected.6 Interestingly, our results revealed that PPARγ KO chondrocytes exhibited significantly enhanced expression of mTOR in both non-surgery and OA conditions compared with chondrocytes from non-surgery control mice and OA surgery control mice. Since mTOR negatively regulates autophagy, we further determined the expression of LC3B, an autophagosome marker for monitoring autophagy. The expression of LC3B II was significantly reduced in control OA chondrocytes compared with control non-surgery chondrocytes. Our results also revealed that PPARγ KO chondrocytes exhibited a significant decrease in LC3B II expression in both non-surgery and OA conditions compared with control chondrocytes from non-surgery mice and OA surgery mice, respectively, thus exhibiting an opposite expression profile observed for mTOR. It was interesting to notice that despite significant differences in the levels of mTOR and LC3B II expression under basal conditions (non-surgery) in PPARγ KO mice chondrocytes compared with control chondrocytes, we did not observe any significant differences in the articular cartilage cellularity at baseline in vivo.

Figure 3.

Aberrant expression of mammalian target for rapamycin (mTOR) and autophagy markers in peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ)-deficient chondrocytes: (A and B) PPARγ expression was significantly (*p<0.05) reduced in chondrocytes extracted from 5-week post osteoarthritis (OA) surgery control mice compared with non-surgery control mice. PPARγ expression was not detected (ND) in both PPARγ knockout (KO) non-surgery and PPARγ KO OA surgery chondrocytes. A significant (*p<0.05) increase in mTOR protein expression and significant decrease in LC3B II expression was observed in control OA chondrocytes compared with control non-surgery chondrocytes as well as PPARγ KO OA chondrocytes compared with PPARγ KO non-surgery chondrocytes. A significant (+p<0.05) increase in mTOR protein expression and decrease in LC3B II expression was observed in both PPARγ KO non-surgery and PPARγ KO OA surgery chondrocytes compared with control non-surgery and control OA chondrocytes, respectively (n=4); (C and D) qPCR analysis showed a significant increase in the messenger RNA (mRNA) expression of mTOR and a significant decrease in the mRNA expression of LC3B, ULK1, ATG5 and BNIP3 in PPARγ KO OA mice chondrocytes compared with control OA mice chondrocytes (n=4, *p<0.05).

qPCR analysis also confirmed a significant increase in mTOR expression and significant reduction in the expression of LC3B and other key autophagy genes including unc-51 like autophagy activating kinase 1 (ULK1) (most upstream autophagy inducer),23 autophagy gene 5 (ATG5) (an autophagy regulator),24 and BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19 kDa protein-interacting protein 3 (BNIP3) (an interactor of LC3 in autophagy)25 in PPARγ KO OA chondrocytes compared with chondrocytes extracted from control OA mice (figure 3C, D).

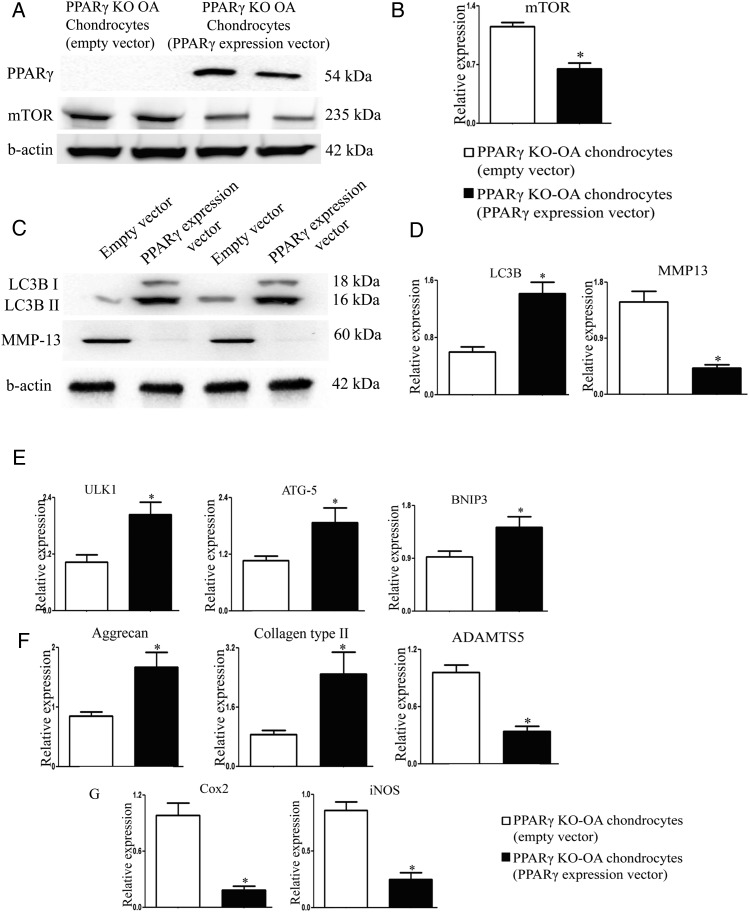

PPARγ regulates mTOR/autophagy signalling pathway and controls the balance between catabolic/anabolic factors in vitro

Since PPARγ deficiency in the chondrocytes resulted in the aberrant expression of catabolic, anabolic and inflammatory markers associated with the dysregulated expression of mTOR and autophagy markers, we hypothesised that PPARγ is involved in the regulation of mTOR/autophagy pathway and may, in part, be responsible for maintaining the balance between catabolic and anabolic processes in the articular cartilage. To test this hypothesis, we transfected PPARγ-deficient OA chondrocytes with PPARγ expression vector to determine if restoration of PPARγ expression can rescue the phenotype of PPARγ KO OA cells. We observed that the restoration of PPARγ expression in KO cells by PPARγ expression vector (figure 4A) was able to downregulate the protein and mRNA expression of mTOR (figure 4A, B), enhance the LC3B II protein expression and LC3B mRNA expression and downregulate protein and mRNA expression of MMP-13 (figure 4C, D). qPCR analysis further showed that the restoration of PPARγ expression in KO cells was able to rescue and upregulate the expression of other autophagy genes (ULK-1, ATG5 and BNIP3) and anabolic factors (collagen type II and aggrecan), as well as downregulate the expression catabolic (ADAMTS-5; a disintegrin and metalloprotease with thrombospondin motifs) and inflammatory markers (iNOS and COX-2) (figure 4E–G).

Figure 4.

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) expression vector rescues the aberrant expression of catabolic, anabolic and inflammatory markers, and the dysregulated expression of mammalian target for rapamycin (mTOR)/autophagy markers in PPARγ knockout osteoarthritis (KO OA) chondrocytes: PPARγ KO chondrocytes (isolated at 5 weeks post-OA surgery) were cultured and transfected with PPARγ expression vector or empty vector. Rescue of PPARγ in PPARγ KO chondrocytes by PPARγ expression vector resulted in: (A and B) decrease in the protein and messenger RNA expression of mTOR (n=4, *p<0.05); (C) increase in LC3B II expression and decrease in MMP-13 expression (n=4), (D) increase in the mRNA expression of LC3B and decrease in the mRNA expression of MMP-13; (E) increase in mRNA expression of ULK1, ATG5 and BNIP3; (F) increase in the expression of aggrecan and collagen type II and decrease in the mRNA expression of ADAMTS-5; (G) decrease in mRNA expression of COX-2 and iNOS; (n=4, *p<0.05).

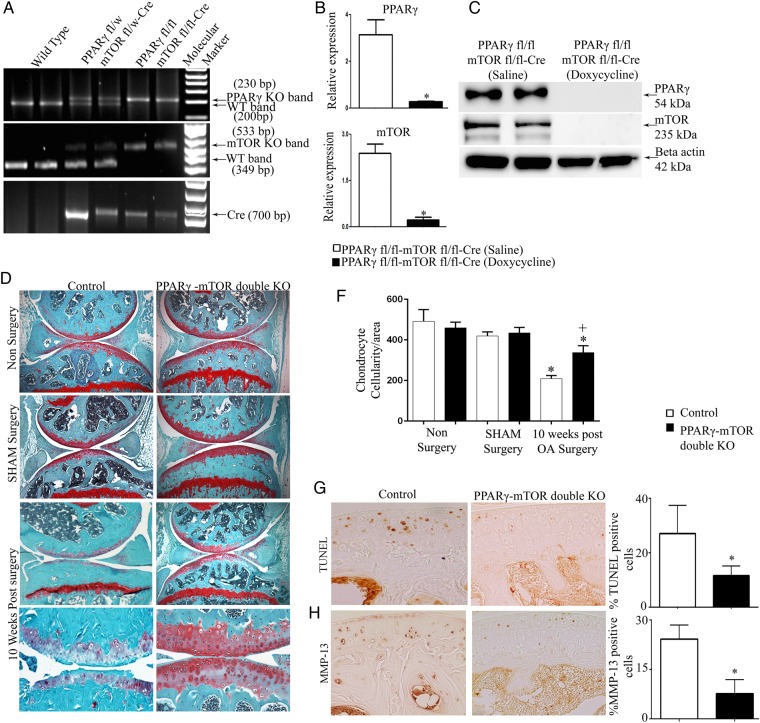

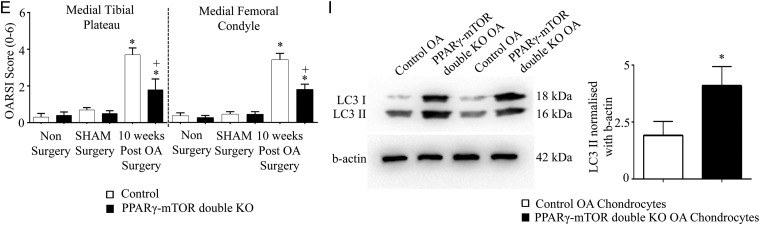

Cartilage-specific PPARγ-mTOR double KO mice exhibit protection from OA

Our results suggest that PPARγ deficiency in part could be responsible for increased mTOR signalling, the inhibition of critical autophagy markers, ultimately resulting in increased catabolic/inflammatory activity (and reduced anabolic activity) within the articular cartilage leading to severe/accelerated OA. To test this in vivo, we generated inducible cartilage-specific PPARγ-mTOR double KO mice (figure 5A–C). These mice were subjected to DMM surgery. Histological analysis (using OARSI scoring) in 10 weeks post-OA surgery demonstrated that PPARγ-mTOR double KO mice were significantly protected from DMM-induced OA associated with the significant protection from cartilage destruction, proteoglycan loss and loss of chondrocytes in both medial tibial plateau and medial femoral condyle compared with control mice (figure 5D, E). The quantification of articular chondrocyte cellularity (figure 5F) and TUNEL staining (figure 5G) further confirmed a significant reduction in chondrocyte cell death in double KO mice compared with control mice at 10 weeks post-OA surgery. Furthermore, we also observed a significant reduction in the percentage of MMP-13-positive cells (figure 5H), and enhanced LC3B II expression in double KO OA chondrocytes compared with control OA chondrocytes (figure 5I).

Figure 5.

Inducible cartilage-specific peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ)-mammalian target for rapamycin (mTOR) double knockout (KO) mouse are protected from destabilisation of medial meniscus (DMM)-induced osteoarthritis (OA): (A) genotyping confirms the presence of the Cre transgene in heterozygote (PPARγfl/w-mTORfl/w) and homozygote (PPARγfl/fl-mTORfl/fl) mice and its absence in wild-type mice; (B and C) qPCR and western blotting analysis of isolated chondrocytes confirmed absence of PPARγ and mTOR expression in PPARγfl/fl-mTORfl/flCre mice treated with doxycycline compared with PPARγfl/fl-mTORfl/flCre mice treated with saline (n=5, *p<0.05); (D) histological analysis using safranin O/fast green staining of 10 weeks post-OA surgery knee joint sections demonstrate that in comparison with control mice, PPARγ-mTOR double KO mice exhibit significant protection from DMM-induced OA associated with reduced cartilage degradation, proteoglycan loss and reduced loss of articular chondrocyte cellularity (n=5, magnification: ×6.2 and ×25); (E) Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) scoring of medial tibial plateau and medial femoral condyle showed a significant increase (*p<0.05) in the OARSI scores in both control OA and PPARγ KO OA mice (10 weeks post-OA surgery) compared with non-surgery and sham surgery control and PPARγ KO mice, respectively. A significant (+p<0.05) reduction in the OARSI score was observed at both medial tibial plateau and medial femoral condyle in PPARγ-mTOR double KO mice compared with control mice at 10 weeks post-OA surgery (n=5, *p<0.05); (F) quantification of articular chondrocyte cellularity revealed significant (*p<0.05) loss of chondrocyte cellularity in both control OA and PPARγ KO OA mice (10 weeks post-OA) compared with non-surgery and sham surgery control and PPARγ KO mice, respectively. Further, comparison between PPARγ-mTOR double KO mice and control mice at 10 weeks post-OA surgery revealed a significant (+p<0.05) protection from articular chondrocyte loss during OA (n=6, *p<0.05); (G and H) a significant decrease in the percentage (%) of TUNEL and MMP-13 positive cells in PPARγ-mTOR double KO OA mice compared with control OA mice at 10 weeks post-OA surgery (n=4, magnification: ×40); (I and H) increase in light chain 3B (LC3B) II expression in PPARγ-mTOR double KO OA mice chondrocytes compared with control OA mice chondrocytes at 10 weeks post-OA surgery (n=4; *p<0.05).

Discussion

Autophagy is a cellular homeostatic process involving the turnover of organelles and proteins by lysosome-dependent degradation pathway.26–28 Autophagy plays a key role in the modulation of cell death/survival, adaptive immunity, inflammation and cellular homeostasis and dysregulation in this homeostatic process has been associated with several disorders, including cardiomyopthies, neurodegeneration and abnormal skeletal development.29 30 mTOR, a serine/threonine protein kinase, is a master negative regulator of autophagy, and modulates growth, proliferation, motility and survival in cells. Akt has been shown to directly phosphorylate and activate mTOR as well as mTOR can negatively regulate PI3 K/Akt activity.31–33

mTOR is upregulated during OA and is associated with the suppression of autophagy signalling in the articular cartilage resulting in decreased chondroprotection, and thus promoting cartilage degeneration.6 Both the pharmacological inhibition and genetic deletion of mTOR has been shown to reduce the severity of experimental OA.6 10 It is, however, unclear which endogenous mediators controls mTOR and autophagy signalling in the articular cartilage. Identifying endogenous mediators that control mTOR/autophagy signalling and, ultimately, the fate of articular cartilage chondrocytes will help generate new therapeutic strategies to modulate cartilage homeostasis and counteract cartilage degeneration.

PPARγ is a ligand-activated transcription factor known to play a key role in inflammation, fibrosis and resolution of tissue repair process. Studies suggest that the activation of this transcription factor is a therapeutic target for OA. It has been shown that agonists of PPARγ exhibit anti-inflammatory and anticatabolic properties in vitro and in vivo, and impart protection from OA in animal models.12 16–18 However, studies using agonists of PPARγ do not elucidate the exact effects mediated by this complex gene. Indeed, some of these agonists have the ability to regulate, in vivo, various other signalling pathways independent of PPARγ. Additionally, the in vivo role of PPARγ in articular cartilage homeostasis is largely unknown.

We have previously reported that germ-line cartilage-specific PPARγ KO mice exhibit early developmental defects and exhibit accelerated spontaneous OA phenotype during adulthood.14 In the present study, we created for the first time, inducible cartilage-specific PPARγ KO mice. Unlike germ-line cartilage-specific PPARγ KO mice, inducible cartilage-specific PPARγ KO mice did not exhibit any developmental defects and spontaneous OA phenotype.

We then subjected these mice to a DMM model of OA. Our results clearly show that the genetic deficiency of PPARγ in the articular cartilage results in accelerated and severe OA phenotype upon DMM surgery. Compared with control mice, cartilage-specific PPARγ KO mice exhibit accelerated articular cartilage degeneration associated with greater articular chondrocyte cell death, proteoglycan loss, enhanced expression of catabolic (MMP-13 and ADAMTS-5) and inflammatory mediators (COX-2 and iNOS) and reduced expression of ECM anabolic factors (aggrecan and collagen type II). Our results further show that both non-surgery (basal condition) and OA surgery PPARγ KO chondrocytes exhibit enhanced mTOR expression and decreased LC3B II expression compared with control non-surgery and control OA mice chondrocytes.

Based on these results, we further wanted to test if the genetic deficiency of PPARγ and subsequent elevation in the expression of mTOR and suppression of autophagy could, in part, be responsible for increased catabolic and inflammatory activity in the articular cartilage resulting in severe OA phenotype in PPARγ KO mice. To test this, we transfected PPARγ-deficient OA chondrocytes with PPARγ expression vector, and observed that the restoration of PPARγ expression in PPARγ KO cells resulted in a significant downregulation in the expression of mTOR and upregulation in the expression of LC3B II as well as elevation in the gene expression of other key autophagy genes. Additionally, the restoration of PPARγ expression in PPARγ KO cells resulted in significant rescue in the expression of collagen type II and aggrecan, and downregulation in the expression of catabolic (MMP13 and ADAMTS-5) and inflammatory markers (iNOS and COX-2) in PPARγ KO OA chondrocytes. To further explore that mTOR and autophagy pathways are indeed responsible for severe OA phenotype observed in PPARγ KO mice, we generated inducible cartilage-specific PPARγ-mTOR double KO mice and subjected these mice to DMM surgery. Results showed that PPARγ-mTOR double KO mice exhibited significant protection from DMM-induced cartilage destruction, proteoglycan loss and loss of chondrocyte-cellularity associated with significant reduction in TUNEL and MMP-13-positive cells and increase in LC3B II expression, thus reversing the accelerated OA phenotype observed in PPARγ KO mice in vivo.

Our in vitro rescue studies using PPARγ expression vector and in vivo studies using PPARγ-mTOR double KO mice show that PPARγ is involved in the regulation of mTOR/autophagy signalling in the articular cartilage. Therefore, the deficiency of PPARγ in the articular cartilage may, in part, be responsible for upregulation in mTOR signalling resulting in the suppression of autophagy and decreased chondroprotection and increased catabolic activity leading to accelerated severe OA. The relationship between PPARγ and autophagy has been previously reported in breast cancer. Zhou et al.34 showed that PPARγ activation by its ligands induces autophagy in breast cancer. Further, interaction between PPARγ and mTOR pathways during lipid uptake and adipogenesis has also been reported.35 36 Our study, for the first time, provides a direct evidence on the role of PPARγ in chondroprotection, in part, by the modulation of mTOR/autophagy signalling in the articular cartilage. Since mTOR is a complex and multifactorial mediator, it is worth mentioning that the PPARγ/mTOR signalling observed in the articular cartilage may also involve other non-autophagy pathways that require further investigation. It would also be interesting to investigate the functional consequences of interaction between PPARγ and two multiprotein mTOR complexes to fully elucidate the relationship between PPARγ and mTOR signalling pathway in the articular cartilage. Since the use of dual inhibitors of PI3K/Akt and mTOR has been proposed as a promising therapeutic approach in OA,37 it would be interesting to identify the exact relationship between PPARγ and PI3K/Akt-mTOR pathways.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Miwand Najafe, Changshan Geng, David Hum, Francois-Cyril Jolicoeur, Frederic Pare and Francois Mineau for their technical assistance.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors were either involved in conception and design, or analysis and interpretation of data. Each author was involved in drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content. Each author gave their final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: This work is supported by MK's Canadian Institutes of Health Research Operating Grant MOP: 126016 and MOP: 106567. FV is a recipient of Graduate PhD award from the Canadian Arthritis Network (CAN)/The Arthritis Society (TAS).

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Kuettner KE, Cole AA. Cartilage degeneration in different human joints. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2005;13:93–103. 10.1016/j.joca.2004.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blaney Davidson EN, Vitters EL, van der Kraan PM, et al. Expression of transforming growth factor-beta (TGFbeta) and the TGFbeta signalling molecule SMAD-2P in spontaneous and instability-induced osteoarthritis: role in cartilage degradation, chondrogenesis and osteophyte formation. Ann Rheum Dis 2006;65:1414–21. 10.1136/ard.2005.045971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Monemdjou R, Fahmi H, Kapoor M. Synovium in the pathophysiology of osteoarthritis. Therapy 2010;7:661–8. 10.2217/thy.10.72 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Monemdjou R, Fahmi H, Pelletier J-P, et al. Metalloproteases in the Pathogenesis of Osteoarthritis. Int J Adv Rheumatol 2010;8:103–10.. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levine B, Klionsky DJ. Development by self-digestion: molecular mechanisms and biological functions of autophagy. Dev Cell 2004;6:463–77. 10.1016/S1534-5807(04)00099-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Y, Vasheghani F, Li YH, et al. Cartilage-specific deletion of mTOR upregulates autophagy and protects mice from osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2014. Published Online First: 20 Mar 2014. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sasaki H, Takayama K, Matsushita T, et al. Autophagy modulates osteoarthritis-related gene expression in human chondrocytes. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:1920–8. 10.1002/art.34323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carames B, Taniguchi N, Seino D, et al. Mechanical injury suppresses autophagy regulators and pharmacologic activation of autophagy results in chondroprotection. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:1182–92. 10.1002/art.33444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carames B, Taniguchi N, Otsuki S, et al. Autophagy is a protective mechanism in normal cartilage, and its aging-related loss is linked with cell death and osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2010;62:791–801. 10.1002/art.27305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carames B, Hasegawa A, Taniguchi N, et al. Autophagy activation by rapamycin reduces severity of experimental osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:575–81. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kapoor M, McCann M, Liu S, et al. Loss of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma in mouse fibroblasts results in increased susceptibility to bleomycin-induced skin fibrosis. Arthritis Rheum 2009;60:2822–9. 10.1002/art.24761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kapoor M, Kojima F, Qian M, et al. Microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 deficiency is associated with elevated peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma: regulation by prostaglandin E2 via the PI3 kinase and AKT pathway. J Biol Chem 2007;282:5356–66. 10.1074/jbc.M610153200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Monemdjou R, Vasheghani F, Fahmi H, et al. Association of cartilage-specific deletion of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma with abnormal endochondral ossification and impaired cartilage growth and development in a murine model. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:1551–61. 10.1002/art.33490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vasheghani F, Monemdjou R, Fahmi H, et al. Adult cartilage-specific peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma knockout mice exhibit the spontaneous osteoarthritis phenotype. Am J Pathol 2013;182:1099–106. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kapoor M, Kojima F, Qian M, et al. Microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 deficiency is associated with elevated peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma: regulation by prostaglandin E2 via the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and Akt pathway. J Biol Chem 2007;282:5356–66. 10.1074/jbc.M610153200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boileau C, Martel-Pelletier J, Fahmi H, et al. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonist pioglitazone reduces the development of cartilage lesions in an experimental dog model of osteoarthritis: in vivo protective effects mediated through the inhibition of key signaling and catabolic pathways. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:2288–98. 10.1002/art.22726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Afif H, Benderdour M, Mfuna-Endam L, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma1 expression is diminished in human osteoarthritic cartilage and is downregulated by interleukin-1beta in articular chondrocytes. Arthritis Res Ther 2007;9:R31 10.1186/ar2151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kobayashi T, Notoya K, Naito T, et al. Pioglitazone, a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonist, reduces the progression of experimental osteoarthritis in guinea pigs. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:479–87. 10.1002/art.20792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barak Y, Nelson MC, Ong ES, et al. PPAR gamma is required for placental, cardiac, and adipose tissue development. Molecular Cell 1999;4:585–95. 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80209-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grover J, Roughley PJ. Generation of a transgenic mouse in which Cre recombinase is expressed under control of the type II collagen promoter and doxycycline administration. Matrix Biol 2006;25:158–65. 10.1016/j.matbio.2005.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Valverde-Franco G, Pelletier JP, Fahmi H, et al. In vivo bone-specific EphB4 overexpression in mice protects both subchondral bone and cartilage during osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:3614–25. 10.1002/art.34638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glasson SS, Chambers MG, Van Den Berg WB, et al. The OARSI histopathology initiative—recommendations for histological assessments of osteoarthritis in the mouse. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2010;18(Suppl 3):S17–23. 10.1016/j.joca.2010.05.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inoki K, Kim J, Guan KL. AMPK and mTOR in cellular energy homeostasis and drug targets. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2012;52:381–400. 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010611-134537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuma A, Hatano M, Matsui M, et al. The role of autophagy during the early neonatal starvation period. Nature 2004;432:1032–6. 10.1038/nature03029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hanna RA, Quinsay MN, Orogo AM, et al. Microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3) interacts with Bnip3 protein to selectively remove endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria via autophagy. J Biol Chem 2012;287:19094–104. 10.1074/jbc.M111.322933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levine B, Kroemer G. Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell 2008;132:27–42. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eskelinen EL, Saftig P. Autophagy: a lysosomal degradation pathway with a central role in health and disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 2009;1793:664–73. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mizushima N, Levine B, Cuervo AM, et al. Autophagy fights disease through cellular self-digestion. Nature 2008;451:1069–75. 10.1038/nature06639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hara T, Nakamura K, Matsui M, et al. Suppression of basal autophagy in neural cells causes neurodegenerative disease in mice. Nature 2006;441:885–9. 10.1038/nature04724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Komatsu M, Waguri S, Ueno T, et al. Impairment of starvation-induced and constitutive autophagy in Atg7-deficient mice. J Cell Biol 2005;169:425–34. 10.1083/jcb.200412022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.LoPiccolo J, Blumenthal GM, Bernstein WB, et al. Targeting the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway: effective combinations and clinical considerations. Drug Resist Updat 2008;11:32–50. 10.1016/j.drup.2007.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harrington LS, Findlay GM, Lamb RF. Restraining PI3K: mTOR signalling goes back to the membrane. Trends Biochem Sci 2005;30:35–42. 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sarbassov DD, Guertin DA, Ali SM, et al. Phosphorylation and regulation of Akt/PKB by the rictor-mTOR complex. Science 2005;307:1098–101. 10.1126/science.1106148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou J, Zhang W, Liang B, et al. PPARgamma activation induces autophagy in breast cancer cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2009;41:2334–42. 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blanchard PG, Festuccia WT, Houde VP, et al. Major involvement of mTOR in the PPARgamma-induced stimulation of adipose tissue lipid uptake and fat accretion. J Lipid Res 2012;53:1117–25. 10.1194/jlr.M021485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim JE, Chen J. regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma activity by mammalian target of rapamycin and amino acids in adipogenesis. Diabetes 2004;53:2748–56. 10.2337/diabetes.53.11.2748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen J, Crawford R, Xiao Y. Vertical inhibition of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway for the treatment of osteoarthritis. J Cell Biochem 2013;114:245–9. 10.1002/jcb.24362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.