Abstract

The objective of this systematic literature review was to determine the association between cardiovascular events (CVEs) and antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and psoriatic arthritis (PsA)/psoriasis (Pso).

Systematic searches were performed of MEDLINE, EMBASE and Cochrane databases (1960 to December 2012) and proceedings from major relevant congresses (2010–2012) for controlled studies and randomised trials reporting confirmed CVEs in patients with RA or PsA/Pso treated with antirheumatic drugs. Random-effects meta-analyses were performed on extracted data.

Out of 2630 references screened, 34 studies were included: 28 in RA and 6 in PsA/Pso. In RA, a reduced risk of all CVEs was reported with tumour necrosis factor inhibitors (relative risk (RR), 0.70; 95% CI 0.54 to 0.90; p=0.005) and methotrexate (RR, 0.72; 95% CI 0.57 to 0.91; p=0.007). Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) increased the risk of all CVEs (RR, 1.18; 95% CI 1.01 to 1.38; p=0.04), which may have been specifically related to the effects of rofecoxib. Corticosteroids increased the risk of all CVEs (RR, 1.47; 95% CI 1.34 to 1.60; p<0.001). In PsA/Pso, systemic therapy decreased the risk of all CVEs (RR, 0.75; 95% CI 0.63 to 0.91; p=0.003).

In RA, tumour necrosis factor inhibitors and methotrexate are associated with a decreased risk of all CVEs while corticosteroids and NSAIDs are associated with an increased risk. Targeting inflammation with tumour necrosis factor inhibitors or methotrexate may have positive cardiovascular effects in RA. In PsA/Pso, limited evidence suggests that systemic therapies are associated with a decrease in all CVE risk.

Introduction

Patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) have increased risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.1 2 Although less evidence has been published so far,3 4 this increased risk is also suspected in patients with psoriasis (Pso), with or without psoriatic arthritis (PsA). Irrespective of classical cardiovascular risk factors, the systemic inflammation characteristic of RA and Pso/PsA plays a pivotal role in increasing cardiovascular risk by accelerating atherosclerosis.5 Vascular inflammation and the related elevated cardiovascular risk may affect all patients with RA, beginning in the early stage of disease (perhaps even preceding clinical onset)6 and worsening with additional classical cardiovascular risk factors.

Many anti-inflammatory strategies have emerged as potential therapeutic approaches for atherosclerosis.7 Likewise, treatment of the underlying inflammatory process could contribute to improved cardiovascular outcomes in patients with RA and Pso/PsA.8 This is reflected in one of the current European League Against Rheumatism recommendations in RA,9 10 which advises achieving remission or low disease activity as early as possible, not only for better structural and functional outcomes, but also to reduce cardiovascular risk. However, it is still open to discussion as to whether targeting systemic inflammation itself with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) reduces the occurrence of cardiovascular events (CVEs) in patients with RA or Pso/PsA.

The purpose of this systematic literature review and meta-analysis was to explore the association between the use of biologics (including tumour necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors), non-biological DMARDs (including methotrexate), corticosteroids and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and CVEs in patients with RA or Pso/PsA.

Methods

A systematic literature review and meta-analysis were performed according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses statement.11

Data sources and searches

A systematic literature search of MEDLINE (via PubMed), EMBASE and the Cochrane Library databases (1960 to December 2012) was performed to identify observational studies and randomised controlled trials that reported CVEs in adults with RA or Pso/PsA treated with biologics (including TNF inhibitors), non-biological DMARDs (including methotrexate), NSAIDs and corticosteroids (see online supplementary eMethods). Searches were restricted to English language. We also searched the proceedings of the American College of Rheumatology, European League Against Rheumatism, American Academy of Dermatology and European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology annual meetings (2010–2012) and hand-searched reference lists for relevant additional studies.

Study selection

Studies were included if they were observational studies or randomised controlled trials that reported relevant confirmed CVEs (including all CVEs, myocardial infarction, heart failure, stroke and/or major adverse cardiac events); included patients with RA or Pso/PsA treated with biologics, non-biological DMARDs, corticosteroids or NSAIDs (or phototherapy for Pso/PsA); and included a suitable control group (another treatment, such as a TNF inhibitor compared with methotrexate, or non-use of the investigative treatment, such as use of a TNF inhibitor compared with non-use of a TNF inhibitor). Studies were excluded if they only reported data on cardiovascular risk factors (eg, diabetes mellitus), intermediate endpoints (eg, lipid levels) or surrogate markers of atherosclerosis (eg, arterial intimae media thickness); reported data on <400 patients; had a follow-up duration <1 year (to ensure that impact of the assessed treatment was most likely to be a true effect and not due to chance in a short duration of observation); included a patient population with a mean age of 80 years or older (to allow homogeneous cross-study populations, as the majority of studies included populations with a mean age of approximately 60 years); or did not have sufficient data to convert to relative risk (RR). Two studies that specifically included veteran patients with RA12 13 were excluded because 90% of the study population comprised men, which is not representative of the classical gender stratification in RA.

One author (CR) screened all titles and abstracts for potential inclusion. Two authors (CR and BH) then independently screened the full text of the selected studies for inclusion in the systematic review and meta-analysis according to the predetermined criteria. Disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two investigators (CR and BH) independently extracted the following data for each study using a predefined data collection form: study design; data sources; sample size; age of the subjects; underlying disease (RA or Pso/PsA); duration of follow-up; treatments under investigation; cardiovascular outcomes of interest; number of outcomes and models of adjustment (age and gender, cardiovascular risk factors, history of cardiovascular disease, RA disease activity, and use of TNF inhibitors, methotrexate, corticosteroids or NSAIDs). HRs, ORs, RRs, rate ratios or mean effect sizes for each drug and comparator, together with their associated 95% CIs, were recorded for each endpoint. When only incident outcomes were reported, the numbers of events in the compared groups were extracted. We contacted authors for missing data when necessary. If studies reported data on several drugs and/or on several cardiovascular endpoints, each value was included in the analysis, so one reference could contribute several different data values to the final meta-analysis. When several models of adjustment were reported, the most adjusted estimates were used in the analysis. Selected studies were assessed for quality using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale, designed to assess the quality of non-randomised studies such as cohort and case–control studies.14 Briefly, this scale allocates points for appropriateness of participant selection (0–4 points), comparability (0–2 points) and exposure or outcome (0–3 points).

Data synthesis and statistical analysis

Extracted data were combined for meta-analysis using Review Manager (RevMan) software (Cochrane Collaboration). When only incident outcomes were reported, RRs were computed. If patient-years of follow-up were available, rate ratios were calculated and used in analysis. The resulting adjusted or unadjusted RRs, HRs and rate ratios were considered equivalent measures of effect size and entered into RevMan. ORs were transformed to RRs.15 16 These measures were generically referred to as risk ratios. For all outcomes, random-effects meta-analyses were conducted. This assumes that different studies were estimating different intervention effects and partly explains the heterogeneity between studies. Forest plots were constructed to summarise the risk ratio estimates and their 95% CIs. These figures present measures of heterogeneity across studies (Cochrane Q statistic, noted as χ2 and the I2 statistic) and a test for overall effect (Z). Funnel plots and Egger’s regression test were also produced to help detect potential publication bias.

Primary and secondary outcomes

The primary outcome was the association between treatment and all CVEs. The secondary outcomes were the association between treatment and myocardial infarction, heart failure, stroke or major adverse cardiac events.

Results

Study selection

We identified 2630 unique references through searching databases, conference proceedings and reference lists (figure 1). Of these, 2526 were excluded as they were not relevant to our topic or related to cardiovascular risk factors or surrogate markers of atherosclerosis. Of the 104 remaining references, 66 were selected for full-text review. Finally, 34 references met the selection criteria for meta-analysis (see online supplementary table S1): 28 in RA (total of 236 525 subjects; 5410 CVEs)17–44 and 6 in Pso/PsA (220 209 subjects; 2701 CVEs).12 45–49

Figure 1.

Search and selection of studies for systematic review and meta-analysis. PsA, psoriatic arthritis; Pso, psoriasis; RA, rheumatoid arthritis.

Cardiovascular outcomes in RA: results of meta-analyses

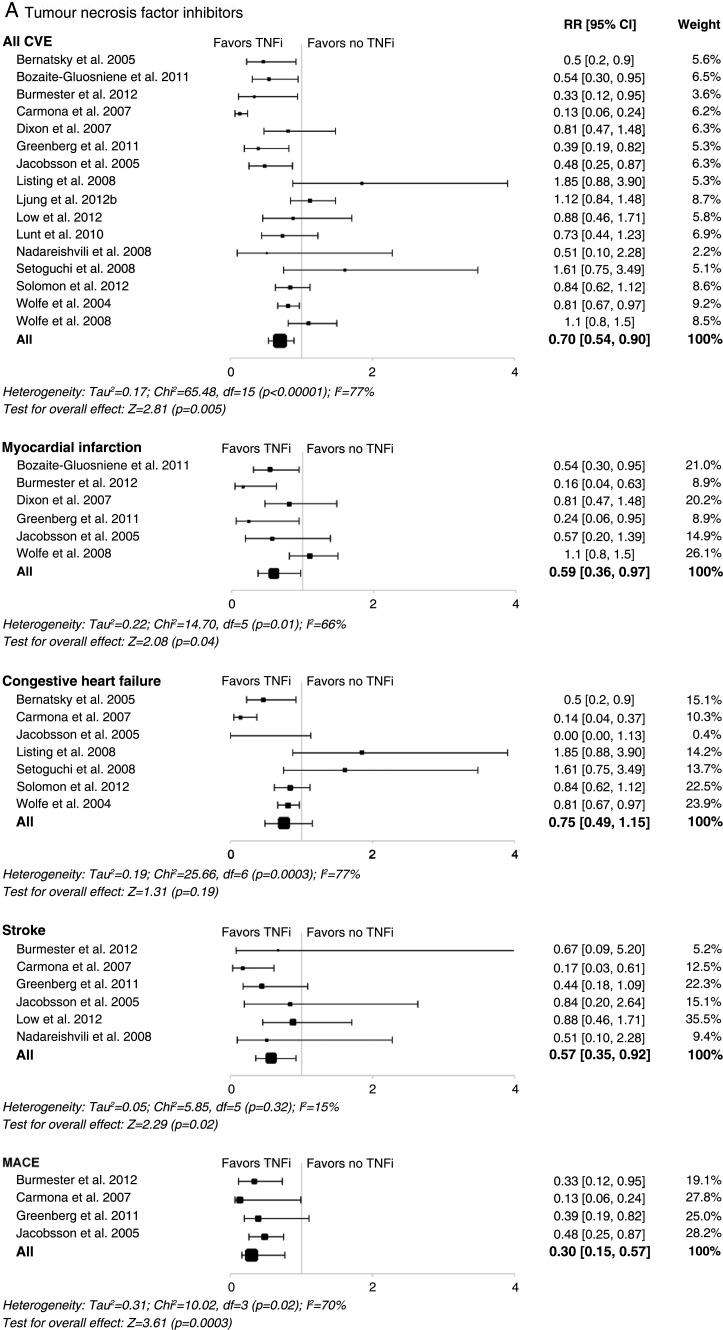

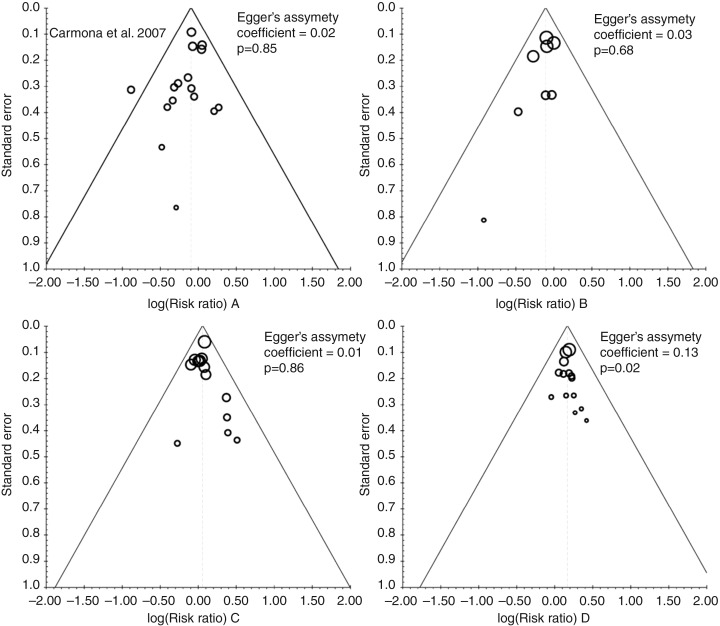

In RA, TNF inhibitors were significantly associated with a reduction in the risk of all CVEs (RR, 0.70; 95% CI 0.54 to 0.90; p=0.005), as well as in myocardial infarctions, strokes and major adverse cardiac events (figure 2A). No significant effect on heart failure was observed (figure 2A). A beneficial association between methotrexate and reduction in the risk of all CVEs (RR, 0.72; 95% CI 0.57 to 0.91; p=0.007) and myocardial infarction was also found (figure 2B). However, in contrast with TNF inhibitors, methotrexate was not associated with a significant decrease in the risk of strokes and major adverse cardiac events, although trends towards decreasing risk of heart failure were found (figure 2B). This may be due to the low number of events included in the meta-analysis, which did not provide sufficient statistical power to observe a differential effect.

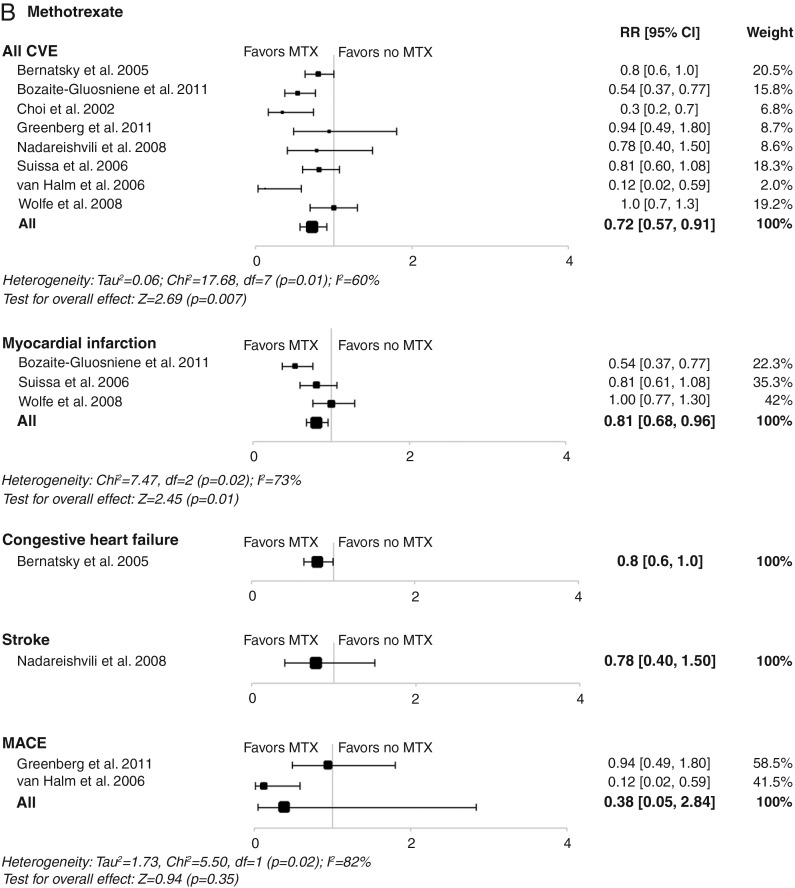

Figure 2.

Meta-analyses of all cardiovascular events and individual cardiovascular events in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with (A) tumour necrosis factor inhibitors; (B) methotrexate; (C) non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; or (D) corticosteroids in controlled studies. Size of data markers indicates relative weight of the study (from random-effects analysis). COX-2, cyclooxygenase-2; CVE, cardiovascular event; MACE, major adverse cardiac event; MTX, methotrexate; RR, relative risk; TNFi, tumour necrosis factor inhibitor.

NSAIDs increased the risk of all CVEs (RR, 1.18; 95% CI 1.01 to 1.38; p=0.04) and strokes. This effect appears mostly driven by cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors (RR, 1.36; 95% CI 1.10 to 1.67; p=0.004) rather than non-selective NSAIDs (RR, 1.08; 95% CI 0.94 to 1.24; p=0.28) (figure 2C). Of note, some studies assessing rofecoxib, which has already been withdrawn from the market, have been included. Hence, we performed separate meta-analyses for rofecoxib and celecoxib. While rofecoxib increased the risk of all CVEs (RR, 1.58; 95% CI 1.24 to 2.00; p<0.001), celecoxib did not (RR, 1.03; 95% CI 0.80 to 1.32; p=0.81) (see online supplementary figure S1). Additionally, NSAIDs did not demonstrate any significant effect on risk of myocardial infarction, heart failure or major adverse cardiac events (figure 2C); however, with few studies included, these findings should be interpreted with caution.

Corticosteroids were associated with an increased risk of all CVEs (RR, 1.47; 95% CI 1.34 to 1.60; p<0.001), as well as risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, heart failure and major adverse cardiac events (figure 2D).

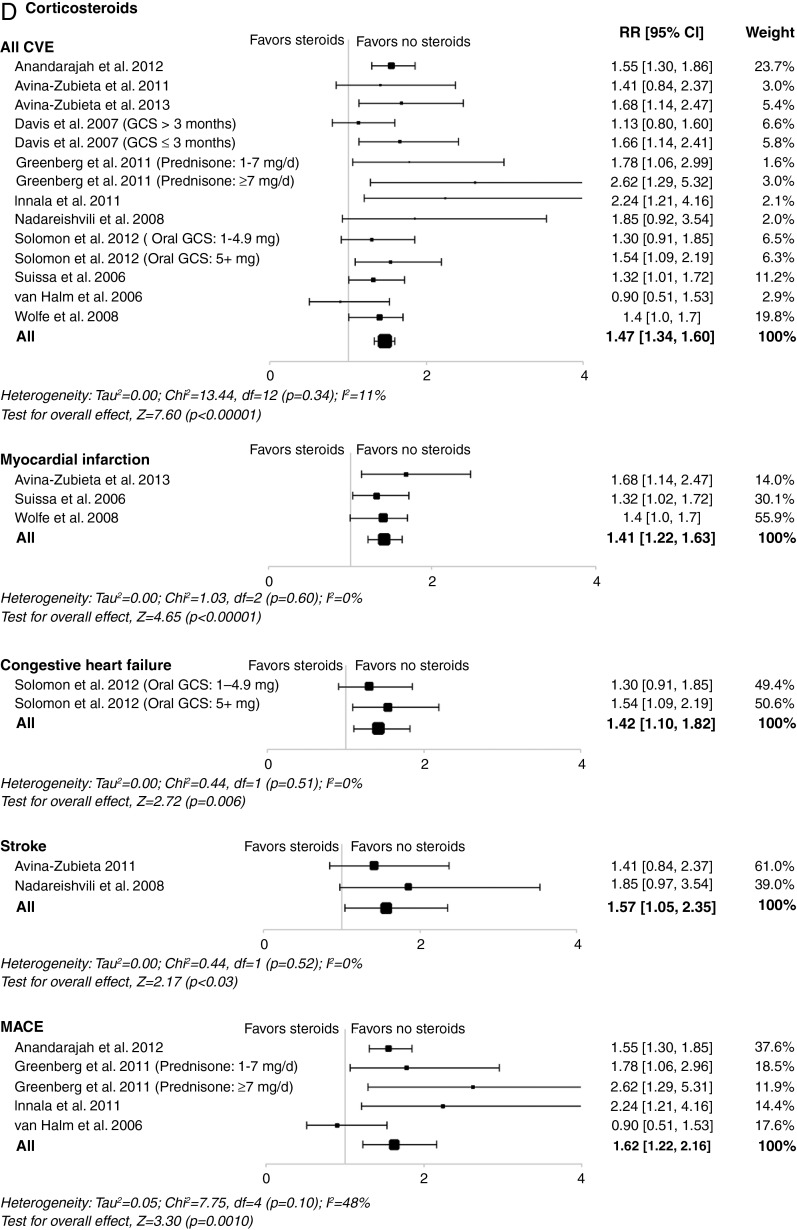

In the meta-analyses evaluating TNF inhibitors or methotrexate, some heterogeneity was found between studies for all endpoints (except stroke). Heterogeneity was only observed for the all CVE endpoint in the meta-analyses evaluating all NSAIDs or COX-2 inhibitors. Of note, no significant heterogeneity was found for the all CVE endpoint in the meta-analyses evaluating non-selective NSAIDs and corticosteroids or for any specific endpoint in the meta-analyses evaluating NSAIDs and corticosteroids. Analysis for publication bias was performed using funnel plots for all CVE endpoints (figure 3). Although subjective, visual inspection did not suggest publication bias for this outcome. Egger’s asymmetry coefficient, known to be low powered, did detect potential bias in the meta-analysis of corticosteroid use (p=0.02, figure 3) and COX-2 inhibitor use (p<0.01; see online supplementary figure S2).

Figure 3.

Funnel plots for the meta-analysis of occurrence of cardiovascular events associated with treatment with (A) tumour necrosis factor inhibitors, (B) methotrexate, (C) non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and (D) corticosteroids. The importance (weight) of each study is proportional to the marker size.

Cardiovascular outcomes in Pso/PsA: results of meta-analyses

Only six studies met our selection criteria in patients with Pso and/or PsA; therefore, we only had sufficient data to evaluate the effect of systemic therapy compared with no systemic therapy or topical treatment on risk of all CVEs. Systemic therapy was associated with a significant decrease in risk of all CVEs in Pso/PsA (RR, 0.75; 95% CI 0.63 to 0.91; p=0.003) (see online supplementary figure S3). No significant heterogeneity was observed (see online supplementary figure S4).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic literature review and meta-analysis of published controlled studies assessing the association between CVEs and use of TNF inhibitors, methotrexate, NSAIDs or corticosteroids in patients with RA or Pso/PsA.

In patients with RA, treatment with TNF inhibitors or methotrexate was associated with a 30% and 28% reduction in the risk of CVEs, respectively, while use of NSAIDs or corticosteroids was associated with 18% and 47% increase in risk of all CVEs, respectively. Moreover, while TNF inhibitors and methotrexate were also found to be associated with a reduction in risk of some specific cardiovascular endpoints, corticosteroids were associated with an increase in risk of all specific outcomes. In patients with Pso/PsA, data suggest that biologics and other DMARDs may be associated with a decreased risk of CVEs, but we acknowledge that evidence is less conclusive than in RA and that further studies are needed.

Compared with the general population, patients with RA have an increased risk of cardiovascular disease or events50 and reduced survival.2 Systemic inflammation is the cornerstone of both RA and atherosclerosis. However, whether effective DMARD-based therapy can ameliorate this increased risk in RA or Pso/PsA is still under debate. Considering these immunomodulatory strategies in atherosclerosis may also provide new perspective in managing cardiovascular disease in the general population. Indeed, in the (non-RA) primary cardiovascular disease prevention Justification for Use of statins in Prevention: an Intervention Trial Evaluating Rosuvastatin randomised controlled trial, the absolute risk of first major adverse cardiac events increased with increasing high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, a measure of systemic inflammation.51 52 This study clearly showed an association between inflammation and cardiovascular risk in otherwise ‘healthy’ individuals. In RA, elevated baseline CRP has been associated with cardiovascular death, persisting after adjustment for classical cardiovascular risk factors, supporting a relevant link between systemic inflammation and risk of cardiovascular disease.5 Hence, by controlling the systemic inflammation, TNF inhibitors and methotrexate may decrease cardiovascular risk. Our present findings in RA support this hypothesis.

Several previous publications have also suggested that TNF inhibitors have a beneficial impact on cardiovascular risk.53 54 As suggested in a systematic literature review,55 another meta-analysis reported that TNF inhibitors in RA may reduce the risk of all CVEs (pooled adjusted RR, 0.46; 95% CI 0.28 to 0.77), myocardial infarction (pooled adjusted RR, 0.81; 95% CI 0.68 to 0.96) and cerebrovascular accident (pooled adjusted RR, 0.69; 95% CI 0.53 to 0.89).15 Our analyses included more studies than those previously reported and our results are consistent with these prior findings. Interestingly, we found no association between TNF inhibitors and risk of heart failure in RA. In the general population with heart failure, TNF-α levels are increased56 and associated with severity of clinical signs and symptoms.57 Experimental heart failure models have suggested that TNF inhibitors may improve ventricular dysfunction58; however, a large clinical trial assessing etanercept in the treatment of congestive heart failure showed no benefit59 while another one found that high-dose infliximab worsened heart failure in patients with moderate-to-severe chronic heart failure.60 Consequently, the presence of severe heart failure remains a contraindication to the use of TNF inhibitors in patients with RA. This may account for our results, given that the selected studies probably included patients with RA without pre-existing heart failure, consistent with a bias by indication. However, one recent study comparing 8656 new users of non-biological DMARDs with 11 587 new users of TNF inhibitors showed that TNF inhibitors were not associated with an increased risk of hospital admissions due to heart failure.37 Further specifically designed trials assessing cardiovascular outcomes are needed to evaluate the use of TNF inhibitors in patients with RA, including those with heart failure.

In RA, methotrexate has recently been associated with a 70% reduction in mortality61 and may also be associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease.62 Consistent with our results, methotrexate has been associated with a 21% lower risk of total cardiovascular disease and an 18% lower risk of myocardial infarction in patients with chronic inflammatory diseases including RA.63 Corticosteroids and NSAIDs are generally considered to have deleterious effects, although little evidence-based data are available in patients with RA. Both non-selective NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors have been demonstrated to increase cardiovascular risk64–66; however, few studies have evaluated the impact of corticosteroids and NSAIDs on CVEs specifically in RA.17–22 36 44 Our meta-analysis in patients with RA revealed that COX-2 inhibitors were associated with an increased risk of all CVEs and strokes, mainly because of rofecoxib, which is now withdrawn from the market. Conversely, non-selective NSAIDs and celecoxib were not associated with increased risk of CVEs. The practical consequence of this finding may be to weigh the benefit–risk ratio of using NSAIDs in patients with RA with higher cardiovascular risk, while not avoiding them at all costs.

The potential harmful cardiovascular effects of corticosteroids are well-known but not strongly evidence based.65 To our knowledge, our meta-analysis is the first to report a deleterious association between corticosteroids and all CVEs, myocardial infarction, heart failure, stroke and major adverse cardiac events in the RA population. Corticosteroids may modulate the risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with RA in two competing directions: by increasing the risk due to deleterious effects on lipids, glucose tolerance, weight gain and hypertension,67 but conversely potentially decreasing the risk by exerting anti-inflammatory and antiproliferative effects on vascular wall. Additionally, corticosteroids may result in two independent effects over time: an immediate effect of current exposure and a long-term cumulative effect of past exposure.22 68 Notably, corticosteroid use has recently been associated with a dose-dependent increased mortality in RA.69

In PsA/Pso, less evidence on risk of CVEs has been published. However, the results of our meta-analysis are consistent with recent reviews,70 71 underlining the need for adequately powered trials to assess the cardiovascular effects of systemic therapy including TNF inhibitors in patients with PsA/Pso.

Interpreting the evidence from observational studies requires caution as these can generate more bias than randomised controlled trials. Hence, only an association between medication use and CVEs can be determined. However, we were unable to find any adequately powered randomised controlled trial assessing the impact of RA therapy on risk of CVEs. Furthermore, the duration of follow-up of most randomised controlled trials in patients with RA or PsA/Pso may not be long enough to investigate the effects of such treatments on CVE rates. Finally, our results are consistent with two large meta-analyses evaluating methotrexate and TNF inhibitors in RA.15 63

Despite the mounting published evidence of an increased cardiovascular risk in patients with RA, few studies have investigated DMARD-based therapeutic strategies to reduce this risk. Therefore, a low number of studies assessing the impact of methotrexate on specific cardiovascular endpoints were included in our analysis. Additionally, lack of sufficient data did not allow for subgroup analyses of dose effect for methotrexate and corticosteroids in RA, or of the influence of psoriasis severity on the impact of systemic therapy on CVE rates in patients with PsA/Pso. No study evaluating the impact of non-TNF inhibitor biologics was found, although several studies evaluating the vascular impact of rituximab (NCT00844714) and tocilizumab (NCT00844714 and NCT01752335) are ongoing in RA.

Another limitation in this analysis is the differences in the cardiovascular definitions and comparators across studies. To mitigate this, we used selection criteria that would provide as homogeneous as possible study populations to provide clinically relevant results.

Conclusion

Our meta-analysis provides important insights into the effect of antirheumatic drugs on CVEs in RA by suggesting that TNF inhibitors and methotrexate decrease the risk of such events while NSAIDs and corticosteroids increase the risk in RA. In PsA/Pso, limited evidence suggests that systemic therapies are associated with a decrease in the risk of all CVEs. While current evidence implies deleterious cardiovascular effects of corticosteroids and COX-2 inhibitors in RA, suppressing diverse mediators of inflammation with methotrexate and TNF inhibitors may have positive cardiovascular effects. Large, prospective, adequately controlled and powered studies are needed to explore the effects of such drugs on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the RA and PsA/Pso populations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr Fred Wolfe and Dr Lotta Ljung, who kindly answered the questions of the authors, Mr André Allard (librarian, Montreal, QC, Canada), who helped perform the systemic literature search, and Mr Louis Coupal (Saint-Lambert, QC, Canada), who helped perform the statistical analysis. CR received a bursary from the Foundation of the University of Montreal Hospital Center (CHUM) for her fellowship. CM was the recipient of a Janssen Ortho Canada fellowship and a Geoffrey Dowling fellowship from the British Association of Dermatologists.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors are responsible for the work described in this paper. All authors were involved in at least one of the following: conception, design, acquisition, analysis, statistical analysis and interpretation of data. All authors were involved in drafting the manuscript and/or reviewing the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors provided final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: This publication summarises the results of the Canadian Dermatology-Rheumatology (DR) Co-morbidity Initiative systematic literature searches (MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, 2010-2012 ACR, EULAR, AAD, EADV abstracts) and consensus-based recommendations from a meeting on the management of comorbidities, held in Toronto, Canada, on 31 May to 1 June 2013, which was sponsored by AbbVie. AbbVie provided funding to Pinnacle Marketing & Education Inc., 7 Daoust, Hudson, Quebec, Canada, to manage the Canadian DR Co-morbidity Initiative that led to this paper. AbbVie paid consultancy fees to BH, JP, LB, SK, RB, WG, JD, CL and JK for their participation in the Canadian DR Co-morbidity Initiative. Travel to and from the meeting was reimbursed. AbbVie provided suggestions for topic ideas for the Canadian DR Co-morbidity Initiative and proposed authors for this paper. AbbVie attended the meeting but was not involved in the development of the paper. AbbVie did have the opportunity to review the final version of the publication. This publication reflects the opinions of the authors. CR prepared a draft outline for coauthors’ comment and approval. Each author reviewed the publication at all stages of development to ensure that it accurately reflects the results of their literature searches and the consensus-based recommendations from the meeting experts. The authors determined final content, and all authors read and approved the final publication. The authors maintained complete control over the content of the paper. No payments were made to the authors for the writing of this publication. Juliette Allport of Leading Edge (part of the Lucid Group), Burleighfield House, Buckinghamshire, UK, subsequently supported incorporation of comments into final drafts for author approval, and editorial styling required by the journal. AbbVie paid Leading Edge for this work.

Competing interests: AM owns stock in Pfizer. JK has acted as consultant, advisor and/or speaker for AbbVie, Amgen, Janssen, Leo Pharma and Novartis. CL has acted as a principal investigator, speaker and/or consultant for AbbVie, Amgen, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Janssen, Leo Pharma, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer and Valeant. JP has received research grants and/or has been a consultant for AbbVie, Actelion, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Janssen, Pfizer, Roche and UCB. SK has received unrestricted educational grants and consultancy fees from AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Janssen, Roche and UCB. JD has received honoraria for participation in advisory boards and as a speaker for AbbVie, Amgen, Janssen and Leo Pharma. LB has received consulting fees, research grants, and honoraria for participation as a speaker for AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, Pfizer, Roche and UCB. RB has received honoraria for participation in advisory boards and/or research grants from AbbVie, Amgen, Celgene, Eli-Lilly Galderma, Incyte, Janssen, Leo Pharma, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer and Tribute. BH has received honoraria for participation in advisory boards and/or research grants from AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, Pfizer, Roche and UCB. WG has received honoraria for participation in advisory boards for AbbVie, Amgen, Bio-K and Janssen and for participation in speaker engagements and consultative meetings for AbbVie, Actelion, Amgen, Janssen, Leo Pharma, Novartis and Roche.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Nicola PJ, Maradit-Kremers H, Roger VL, et al. . The risk of congestive heart failure in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based study over 46 years. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:412–20. 10.1002/art.20855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Solomon DH, Karlson EW, Rimm EB, et al. . Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in women diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis. Circulation 2003;107:1303–7. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000054612.26458.B2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coumbe AG, Pritzker MR, Duprez DA. Cardiovascular risk and psoriasis: beyond the traditional risk factors. Am J Med 2014;127:12–18. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dowlatshahi EA, Kavousi M, Nijsten T, et al. . Psoriasis is not associated with atherosclerosis and incident cardiovascular events: the Rotterdam Study. J Invest Dermatol 2013;133:2347–54. 10.1038/jid.2013.131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goodson NJ, Symmons DP, Scott DG, et al. . Baseline levels of C-reactive protein and prediction of death from cardiovascular disease in patients with inflammatory polyarthritis: a ten-year followup study of a primary care-based inception cohort. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:2293–9. 10.1002/art.21204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kerola AM, Kerola T, Kauppi MJ, et al. . Cardiovascular comorbidities antedating the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:1826–9. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roubille F, Kritikou EA, Roubille C, et al. . Emerging anti-inflammatory therapies for atherosclerosis. Curr Pharm Des 2013;19:5840–9. 10.2174/13816128113199990351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roubille C, Haraoui B. Important issues at heart: cardiovascular risk management in rheumatoid arthritis. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis 2013;5:163–5. 10.1177/1759720X13491853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smolen JS, Landewe R, Breedveld FC, et al. . EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:964–75. 10.1136/ard.2009.126532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peters MJ, Symmons DP, McCarey D, et al. . EULAR evidence-based recommendations for cardiovascular risk management in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other forms of inflammatory arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:325–31. 10.1136/ard.2009.113696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:264–9, W64 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prodanovich S, Ma F, Taylor JR, et al. . Methotrexate reduces incidence of vascular diseases in veterans with psoriasis or rheumatoid arthritis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005;52:262–7. 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al-Aly Z, Pan H, Zeringue A, et al. . Tumor necrosis factor-alpha blockade, cardiovascular outcomes, and survival in rheumatoid arthritis. Transl Res 2011;157:10–18. 10.1016/j.trsl.2010.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abou-Setta AM, Beaupre LA, Rashiq S, et al. . Comparative effectiveness of pain management interventions for hip fracture: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:234–45. 10.7326/0003-4819-155-4-201108160-00346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barnabe C, Martin BJ, Ghali WA. Systematic review and meta-analysis: anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha therapy and cardiovascular events in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63:522–9. 10.1002/acr.20371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang J, Yu KF. What's the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. JAMA 1998;280:1690–1. 10.1001/jama.280.19.1690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nadareishvili Z, Michaud K, Hallenbeck JM, et al. . Cardiovascular, rheumatologic, and pharmacologic predictors of stroke in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a nested, case-control study. Arthritis Rheum 2008;59:1090–6. 10.1002/art.23935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watson DJ, Rhodes T, Cai B, et al. . Lower risk of thromboembolic cardiovascular events with naproxen among patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:1105–10. 10.1001/archinte.162.10.1105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suissa S, Bernatsky S, Hudson M. Antirheumatic drug use and the risk of acute myocardial infarction. Arthritis Rheum 2006;55:531–6. 10.1002/art.22094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davis JM III, Maradit Kremers H, Crowson CS, et al. . Glucocorticoids and cardiovascular events in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based cohort study. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:820–30. 10.1002/art.22418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Avina-Zubieta JA, Abrahamowicz M, Choi HK, et al. . Risk of cerebrovascular disease associated with the use of glucocorticoids in patients with incident rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based study. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:990–5. 10.1136/ard.2010.140210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Avina-Zubieta JA, Abrahamowicz M, De Vera MA, et al. . Immediate and past cumulative effects of oral glucocorticoids on the risk of acute myocardial infarction in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2013;52:68–75. 10.1093/rheumatology/kes353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bernatsky S, Hudson M, Suissa S. Anti-rheumatic drug use and risk of hospitalization for congestive heart failure in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2005;44:677–80. 10.1093/rheumatology/keh610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carmona L, Descalzo MA, Perez-Pampin E, et al. . All-cause and cause-specific mortality in rheumatoid arthritis are not greater than expected when treated with tumour necrosis factor antagonists. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:880–5. 10.1136/ard.2006.067660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dixon WG, Watson KD, Lunt M, et al. . Reduction in the incidence of myocardial infarction in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who respond to anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha therapy: results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:2905–12. 10.1002/art.22809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choi HK, Hernan MA, Seeger JD, et al. . Methotrexate and mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a prospective study. Lancet 2002;359:1173–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08213-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garner SE, Fidan DD, Frankish RR, et al. . Rofecoxib for rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005:CD003685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greenberg JD, Kremer JM, Curtis JR, et al. . Tumour necrosis factor antagonist use and associated risk reduction of cardiovascular events among patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:576–82. 10.1136/ard.2010.129916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Innala L, Moller B, Ljung L, et al. . Cardiovascular events in early RA are a result of inflammatory burden and traditional risk factors: a five year prospective study. Arthritis Res Ther 2011;13:R131 10.1186/ar3442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jacobsson LT, Turesson C, Gulfe A, et al. . Treatment with tumor necrosis factor blockers is associated with a lower incidence of first cardiovascular events in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2005;32:1213–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Listing J, Strangfeld A, Kekow J, et al. . Does tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibition promote or prevent heart failure in patients with rheumatoid arthritis? Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:667–77. 10.1002/art.23281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lunt M, Watson KD, Dixon WG, et al. . No evidence of association between anti-tumor necrosis factor treatment and mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register. Arthritis Rheum 2010;62:3145–53. 10.1002/art.27660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Setoguchi S, Schneeweiss S, Avorn J, et al. . Tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonist use and heart failure in elderly patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Am Heart J 2008;156:336–41. 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.02.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Halm VP, Nurmohamed MT, Twisk JW, et al. . Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs are associated with a reduced risk for cardiovascular disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a case control study. Arthritis Res Ther 2006;8:R151 10.1186/ar2045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wolfe F, Michaud K. Heart failure in rheumatoid arthritis: rates, predictors, and the effect of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy. Am J Med 2004;116:305–11. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.09.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wolfe F, Michaud K. The risk of myocardial infarction and pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic myocardial infarction predictors in rheumatoid arthritis: a cohort and nested case-control analysis. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:2612–21. 10.1002/art.23811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Solomon DH, Rassen JA, Kuriya B, et al. . Heart failure risk among patients with rheumatoid arthritis starting a TNF antagonist. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:1813–18. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Low AS, Lunt M, Mercer LK, et al. . Association between anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy and the risk of ischemic stroke in subjects with rheumatoid arthritis. Results from the British Society For Rheumatology Biologics Registers-Rheumatoid Arthritis (BSRBR-RA). [abstract]. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:828. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anandarajah AP, Saunders KC, Reed GW, et al. . Major adverse cardiovascular events are more common in rheumatoid arthritis than in psoriatic arthritis and are associated with different risk factors. [abstract]. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:2221. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bozaite-Gluosniene R, Tang X, Kirchner HL, et al. . Reduced cardiovascular risk with use of methotrexate and tumor necrosis factor-inhibitors in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. [abstract]. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63:719. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Biki A, Tang X, Kirchner HL, et al. . Prolonged hydroxychloroquine use is associated with decreased incidence of cardiovascular disease in rheumatoid arthritis patients. [abstract]. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63:1168. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Burmester G, Emery P, Signorovitch J, et al. . The effects of adalimumab on risk of major adverse cardiovascular events in rheumatoid arthritus: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. [abstract]. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:359 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-eular.2602 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ljung L, Rantapää-Dahlqvist S, Askling J, et al. . The risk of acute coronary syndromes in RA in relation to TNF inhibitors and risks in the general populatiohn: a national cohort study. [abstract]. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:518 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-eular.308721989544 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lindhardsen J, Gislason GH, Jacobsen S, et al. . Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a nationwide cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1515–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abuabara K, Lee H, Kimball AB. The effect of systemic psoriasis therapies on the incidence of myocardial infarction: a cohort study. Br J Dermatol 2011;165:1066–73. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10525.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ahlehoff O, Skov L, Gislason G, et al. . Cardiovascular disease event rates in patients with severe psoriasis treated with systemic anti-inflammatory drugs: a Danish real-world cohort study. J Intern Med 2013;273:197–204. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2012.02593.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen YJ, Chang YT, Shen JL, et al. . Association between systemic antipsoriatic drugs and cardiovascular risk in patients with psoriasis with or without psoriatic arthritis: a nationwide cohort study. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:1879–87. 10.1002/art.34335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lan CC, Ko YC, Yu HS, et al. . Methotrexate reduces the occurrence of cerebrovascular events among Taiwanese psoriatic patients: a nationwide population-based study. Acta Derm Venereol 2012;92:349–52. 10.2340/00015555-1283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu JJ, Poon KY, Channual JC, et al. . Association between tumor necrosis factor inhibitor therapy and myocardial infarction risk in patients with psoriasis. Arch Dermatol 2012;148:1244–50. 10.1001/archdermatol.2012.2502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Avina-Zubieta JA, Thomas J, Sadatsafavi M, et al. . Risk of incident cardiovascular events in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:1524–9. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ridker PM, Danielson E, Fonseca FA, et al. . Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C-reactive protein. N Engl J Med 2008;359:2195–207. 10.1056/NEJMoa0807646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ridker PM, MacFadyen J, Libby P, et al. . Relation of baseline high-sensitivity C-reactive protein level to cardiovascular outcomes with rosuvastatin in the Justification for Use of statins in Prevention: an Intervention Trial Evaluating Rosuvastatin (JUPITER). Am J Cardiol 2010;106:204–9. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maki-Petaja KM, Elkhawad M, Cheriyan J, et al. . Anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy reduces aortic inflammation and stiffness in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Circulation 2012;126:2473–80. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.120410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Solomon DH, Curtis JR, Saag KG, et al. . Cardiovascular risk in rheumatoid arthritis: comparing TNF-alpha blockade with nonbiologic DMARDs. Am J Med 2013;126:730.e9–e17. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.02.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Westlake SL, Colebatch AN, Baird J, et al. . Tumour necrosis factor antagonists and the risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic literature review. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011;50:518–31. 10.1093/rheumatology/keq316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Levine B, Kalman J, Mayer L, et al. . Elevated circulating levels of tumor necrosis factor in severe chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med 1990;323:236–41. 10.1056/NEJM199007263230405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McMurray J, Abdullah I, Dargie HJ, et al. . Increased concentrations of tumour necrosis factor in “cachectic” patients with severe chronic heart failure. Br Heart J 1991;66:356–8. 10.1136/hrt.66.5.356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kadokami T, Frye C, Lemster B, et al. . Anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha antibody limits heart failure in a transgenic model. Circulation 2001;104:1094–7. 10.1161/hc3501.096063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mann DL, McMurray JJ, Packer M, et al. . Targeted anticytokine therapy in patients with chronic heart failure: results of the Randomized Etanercept Worldwide Evaluation (RENEWAL). Circulation 2004;109:1594–602. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000124490.27666.B2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chung ES, Packer M, Lo KH, et al. . Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, pilot trial of infliximab, a chimeric monoclonal antibody to tumor necrosis factor-alpha, in patients with moderate-to-severe heart failure: results of the anti-TNF Therapy Against Congestive Heart Failure (ATTACH) trial. Circulation 2003;107:3133–40. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000077913.60364.D2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wasko MC, Dasgupta A, Hubert H, et al. . Propensity-adjusted association of methotrexate with overall survival in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:334–42. 10.1002/art.37723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Westlake SL, Colebatch AN, Baird J, et al. . The effect of methotrexate on cardiovascular disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic literature review. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010;49:295–307. 10.1093/rheumatology/kep366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Micha R, Imamura F, Wyler von Ballmoos M, et al. . Systematic review and meta-analysis of methotrexate use and risk of cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol 2011;108:1362–70. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.06.054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Trelle S, Reichenbach S, Wandel S, et al. . Cardiovascular safety of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: network meta-analysis. BMJ 2011;342:c7086 10.1136/bmj.c7086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Roubille C, Martel-Pelletier J, Davy JM, et al. . Cardiovascular adverse effects of anti-inflammatory drugs. Antiinflamm Antiallergy Agents Med Chem 2013;12:55–67. 10.2174/1871523011312010008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Coxib and traditional NSAID Trialists’ (CNT) Collaboration Bhala N, Emberson J, Merhi A, et al. . Vascular and upper gastrointestinal effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: meta-analyses of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet 2013;382:769–79. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60900-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Panoulas VF, Douglas KM, Stavropoulos-Kalinoglou A, et al. . Long-term exposure to medium-dose glucocorticoid therapy associates with hypertension in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47:72–5. 10.1093/rheumatology/kem311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wei L, MacDonald TM, Walker BR. Taking glucocorticoids by prescription is associated with subsequent cardiovascular disease. Ann Intern Med 2004;141:764–70. 10.7326/0003-4819-141-10-200411160-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.del Rincon I, Battafarano DF, Restrepo JF, et al. . Glucocorticoid dose thresholds associated with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014;66:264–72. 10.1002/art.38210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hugh J, Van Voorhees AS, Nijhawan RI, et al. . From the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation: The risk of cardiovascular disease in individuals with psoriasis and the potential impact of current therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014;70:168–77. 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.09.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Armstrong AW, Brezinski EA, Follansbee MR, et al. . Effects of biologic agents and other Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs on cardiovascular outcomes in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: a systematic review. Curr Pharm Des 2014;20:500–12. 10.2174/138161282004140213123505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.