Abstract

The British National Formulary has been in existence for over 30 years. The prescribing of medicines for children has been less well organized. Many medicines used in children have never been tested in the appropriate age groups and have been prescribed ‘off-label’. This has led to safety issues and concerns that children continued to be treated as second-class citizens. The first attempt at the development of a national formulary specifically for prescribing in children occurred in 1999 with the publication of ‘Medicines for Children’. This generated much national and international interest resulting in the government agreeing to fund the development and production of the first British National Formulary for Children in 2005. This article charts the process and progress of the formulary to the present day.

Keywords: Medicines for Children, National Children's Formulary, off-label, unlicensed

Introduction

Children have existed on the planet for as long as adults but have not been afforded the same status ratings. Perhaps one of the first major events to truly highlight their plight was the recognition that they were the recipients of the effects which thalidomide conferred on the developing fetus. Despite the horrific and devastating signs of absent limbs and phocomelia in the late 1950s and early 1960s it remained insufficiently appreciated that most children often respond differently to medicines than do adults. Many medicines continue to receive a license for use in adults but without being tested in younger people. They are also prescribed for use in teenagers, children and babies. The term for this is ‘off-label prescribing’.

For decades, therefore, many medicines with a marketing authorization for use in adults, but untested in children, have been supplied to children not licensed for a particular indication, not licensed for use in that age, in a formulation often unsuitable for that child or not tested in children given by that particular route of administration.

Over many years local institutions have developed their own excellent children's formularies (such as the Birmingham Paediatric Vade-Mecum, the Sheffield Children's Formulary, the Evelina Hospital Children's Formulary) but no comprehensive national plan was developed in the UK until the 1990s. Studies by Turner et al. in 1996 and 1998 showed 31% prescription episodes in a paediatric intensive care unit (PICU) were off-label or unlicensed and 70% of patients received at least one unlicensed or off-label medicine 1. On paediatric wards 25% of prescriptions were unlicensed or off-label and 36% received at least one unlicensed or off-label medicine 2.

In 1996 the Joint Report of the (then) British Paediatric Association and the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry 3 made recommendations about future clinical trials in children, the division of prescription dosages into age bands and the surveillance of unlicensed medicines usage in children. In 1997 their views were shared by the Select Committee on Health who urged the Department of Health (DoH) to implement the 1996 recommendations 4. In 1999 Conroy et al. showed in a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) that of 455 prescription episodes, 337 were classified as ‘off-label’ and 45 were unlicensed 5. Professor Sir David Hull said in his commentary after the Conroy paper ‘The only way to protect the best interests of children is for the professions as a whole, those who prescribe, dispense or administer drugs to infants and children, to identify the problems, collect the information and keep each other informed through an agreed formulary’.

Professor Hull was the Founding Chair of the Joint Standing Committee for Medicines of the Royal Collage of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) and the Neonatal and Paediatric Pharmacists Group (NPPG). We owe much gratitude to him for his determination, clarity of thought and vision for the future that a national formulary for children is now at the core of our prescribing for children within the UK and beyond.

The beginnings of a national formulary

From the Joint Standing Committee for Medicines in the early 1990s 12 members were elected to become the Formulary Committee. Membership comprised pharmacists, paediatricians, a general practitioner and a dietician. Each committee member agreed to act as an editor for one section of the formulary.

Volunteers were then sought from members of the RCPCH and NPPG. A clinician and a pharmacist were paired together to prepare guidelines on prescribing and monographs for whatever medicines they recommended in their chapter. There was no shortage of volunteers willing to participate as everyone felt the development of a national paediatric formulary was urgently needed. The RCPCH is composed of paediatricians with special interests (e.g. nephrology, neurology, cardiology, respiratory etc.) so each special interest group was approached through its Chair to elect a specific volunteer for a specific matching chapter. A similar exercise took place with the NPPG to choose the most suitable pharmacist for each chapter depending on experience and expertise. General paediatricians were also approached as were those specializing in NICU, PICU and emergency medicine.

A first draft was prepared and then edited by the Formulary Committee as a whole. To try to ensure balance and uniformity the layout of each chapter was scrutinized and altered to prevent piecemeal development with no cohesion. This resulted in a second draft. At this stage it was decided to involve as many paediatricians and paediatric pharmacists as possible so each chapter was sent to a large number of colleagues for their comments, criticisms and recommendations. General and specialist pharmacists were invited and became involved. Altogether there were over 40 reviewers and over 80 contributors. From all of their comments and suggestions a third draft was produced. The editors carefully went to work on this, producing a final edition which was published in 1999 under the auspices of RCPCH Publications. Approximately 3000 hard copies of the children's formulary were printed under the title ‘Medicines for Children’ (MfC). The formulary was 780 pages long. There were introductory chapters discussing how to calculate body surface area needed for the dosage regimes for some medicines, unlicensed medicine usage in children and the administration of medicines. There were 26 guidelines separated into different speciality medical areas (life-support, poisoning, pain management, fever, infections, vaccines, vitamins, ENT, respiratory, cardiac etc.) and a list of all medicines recommended for use in children. These guidelines occupied 593 pages. The medicines were placed alphabetically by their approved name assuming that those prescribing for children knew the approved name of each. At the end of the formulary there were 50 pages of nutritional tables containing information on specialist milks, feeds and allied formulas.

The formulary was distributed to all secondary care and tertiary care paediatric centres as well as to some general practices. A smaller, ‘Pocket Medicines for Children’ booklet (16 cm × 9 cm × 1.5 cm) for use by trainee doctors, was produced in 2001 containing 253 pages. The print run for this small, pocket booklet edition was very similar to the print run for the full-sized formulary giving a combined total of approximately 6000 hard copies.

Both of the above publications were revised and republished in 2003 with similar print runs. This meant, however, that only around 6000 copies of the full-sized ‘Medicines for Children’ were printed over a 5 year period. There was no mechanism for regularly updating as new medicines received their first marketing authorization and the vast majority of prescribers for children in primary care had no formulary to hand. It had been estimated that there were over 220 000 prescribers of medicines to children within the UK so clearly most were being left out of the distribution

In August 2004 the DoH published its ‘Strategy on Medicines for Children’. In it was recorded ‘Health professionals need the latest information so they can make the right choices about the medicines and treatments for their younger patients and that is why the new British Formulary for Children is so important’. The then Health Minister, Lord Warner, stated that the DoH would provide funding for its publication and distribution as soon as the formulary was ready.

The British National Formulary for Children project

The plan was to produce a British National Formulary for Children (BNFC) similar in layout to the already popular British National Formulary (BNF) in use primarily for adult patients. The process was not dissimilar to that described above for the production of ‘Medicines for Children’. A Paediatric Formulary Committee was developed, comprising expert advisors from paediatric and pharmacy colleagues together with editorial staff already employed within the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS) headquarters in London. The committee would elect a paediatrician as Chair and have representatives from the RCPCH, NPPG, BMA and RPS. Representatives were also elected from the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) and from the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA).

Clinical advisors were appointed for each clinical area and sub-specialty to provide expert opinion and advice on specific subjects and to resolve any practical prescribing, clinical or pharmaceutical issue. Five new additional editorial staff were appointed who were supported by staff already undertaking editorial work for the adult BNF at the RPS. The project identified all medicines which were licensed for use in children and the newborn. It also identified medicines in common usage in the newborn and children but which were not specifically licensed for that purpose. A third group of medicines identified were those which were unlicensed but for which good evidence existed on their safety and their efficacy. The age range of children to be included in the formulary was from birth to 18 years of age. The project covered all healthcare professionals involved in prescribing, dispensing and administering medicines to children in primary, secondary and tertiary care.

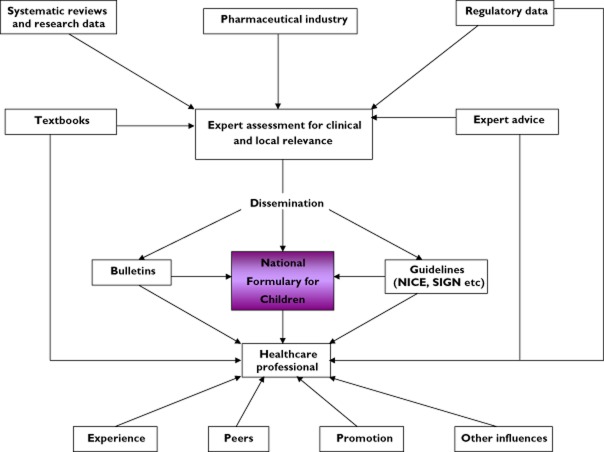

It was a huge project as can be seen by the sources of information used (Table 1) and the flow diagram (Figure 1) explaining how the information was synthesized and progressed.

Table 1.

Sources of information scrutinized during development of the first edition of the BNFC

| • Summary of product characteristics (SPCs) | • Statutory information from the DoH, MHRA, EMEA etc. |

| • Expert clinical and pharmaceutical advisers | • Comments from readers |

| • International medical literature | • Comments from the pharmaceutical industry and the ABPI |

| • Cochrane systematic reviews | |

| • Consensus guidelines | |

| • Reference books | |

| • Expert paediatric centres |

Figure 1.

Flow diagram indicating the complexity of communications and information for development of the BNFC

There were four stages to the project:

The production of the first edition of BNFC using the best information available from MfC and BNF together with many other reference sources (August 2005).

The initial development of an electronic version (September 2005).

The gathering of opinions and suggestions from stakeholders following distribution of the formulary to them (August–December 2005).

Further development of the formulary content and additional sections considered necessary as a result of the feedback.

One issue pertinent to children is whether the dosage of a medication should be related to the age of the child or the weight of the child. This was recently debated in an article and a subsequent editorial in relation to the prescribing of paracetamol. The discussion highlighted the complexity of what might be considered by some to be a relatively simple decision 6,7.

In general the style was developed in a similar fashion to that as laid out in the BNF. Guidance notes were developed as were drug monographs in each chapter. However, special note was made about the licensed status in children and dosages recommended were quoted by specified age bands rather than the broader three categories of ‘infant’, ‘child’ and ‘adolescent’. Clearly there is overlap in children's development within and between different age bandings so some supporting information was needed about the management of certain medicines on this issue.

It was agreed that best practice national guidelines would be published within the BNFC when they became available and, where possible, pharmacokinetic information about absorption, bioavailability, tissue distribution and routes of elimination would be developed and included.

For the first time, the formulary would be able to offer all available information from all available sources on medicines used in children, their licensed status and authoritatively recommend when specialist paediatricians should become involved in or supervise the child's management. MHRA information on children's prescribing and medicines issues would be included and all NHS GPs and pharmacists would receive a copy free of charge. When this first edition of the British National Formulary for Children was published the print run was well over 150 000 copies, contrasting hugely with the print run for the original Medicines for Children formularies of 1999 and 2003.

The project was a huge success. The first edition of BNFC was published in September 2005. Since then there have been yearly hard copy updates every July, the most recent edition being BNFC 2013–2014.

Over the past decade the Paediatric Formulary Committee (PFC) has usually met 4 monthly to ensure each new edition of BNFC included all new information either about individual new medicines, nationally approved guidelines or new indications for older, established medicines. Numerous editors responsible for different BNFC chapters have worked tirelessly to collate all this information, send it to expert advisers for approval and where necessary bring it to the attention of the PFC for a face-to-face decision about the wording of changes which were not straightforward or which were complex or perhaps controversial. Each word change or new word insertion into the BNFC received a check by four different editors to prevent any transcription errors and ensure the highest possible quality of information.

To rely on editorial changes only once yearly when the new print copy becomes available means that some information is outdated soon after any new annual edition is published. To counteract this, the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) has requested that the electronic database of BNFC is updated at monthly intervals. To this end a BNFC electronic forum has been set up where members of the BNFC committee are given information by e-mail about changes needed to be included in the electronic version of the BNFC. Committee members e-mail their views which are collated by the committee Chair and a decision is made to accept or decline the changes. Where the committee has varying views about the changes, these issues are tabled for discussion at the next face-to-face committee meeting to help agree the final decision. One of the other articles in this special edition related to paediatric medications discusses the impact of the recent paediatric medicines legislation and regulation in Europe. The belief is that there will be a greater need to update frequently new information as more studies are undertaken on the development of new medicines for use in children in the future. We all believe that these monthly updates will become increasingly important for this reason.

I hope it can be seen that the development of the BNFC has been and continues to be a robust and thorough process. As electronic databases now begin to come to the fore the BNFC in all its manifestations (electronic database, App, Formulary Complete, BNFC print copy etc.) is an excellent formulary respected throughout the UK and, indeed, used worldwide.

Competing Interests

The author has completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declares no support from any organization for the submitted work, no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

References

- Turner S, Gill A, Nunn T, Choonara I. Use of ‘off label’ and unlicensed drugs in paediatric intensive care unit. Lancet. 1996;347:549–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner S, Longworth A, Nunn AJ, Choonara I. Unlicensed and off label drug use in paediatric wards: prospective study. BMJ. 1998;316:343–345. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7128.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BPA/ABPI. 1996. Licensing Medicines for Children. Joint Report. British Paediatric Association and the Association of British Pharmaceutical Industry. London: BPA/ABPI.

- House of Commons Health Committee. 1997;1 The Specific Health Needs of Children and Young People. Second Report. Vol. House of Commons Health Committee. [Google Scholar]

- Conroy S, McIntyre J, Choonara I. Unlicensed and off label drug use in neonates. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1999;80:F142–145. doi: 10.1136/fn.80.2.f142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyers S, Fingleton J, Eastwood A, Perrin K, Beasley R. British National Formulary for Children: the risk of inappropriate paracetamol prescribing. Arch Dis Child. 2012;97:279–282. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2011-300464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenney W. Paracetamol prescription by age or by weight? Arch Dis Child. 2012;97:277–278. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2011-301374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]