Medical malpractice is defined as an adverse outcome that causes injury or harm which occurs after a physician–patient relationship establishes the duty of care.1 There must be negligence by provider which is usually interpreted as failure to provide the standard of care and direct causality between negligence and outcome. Litigation is an unfortunate consequence of medical complications although in my experience, whether or not malpractice occurred is often unrelated to whether or not a lawsuit is filed. People usually file a lawsuit because of an unexpected, bad outcome, not necessarily because malpractice was committed. Errors in medicine happen commonly, fortunately, most do not result in patient harm. Clearly, a bad outcome does not necessarily indicate malpractice but most patients are not in a position to determine whether or not true malpractice has transpired.

Complications are unavoidable and most complications are defensible except for a special category referred to as “res ipsa loquitur” which is loosely translated to mean “the event speaks for itself.” These are complications that are so egregious that by definition, negligence has occurred. “Never events” such as retained foreign bodies and air embolism are often referred to as “res ipsa loquitur.” Incidentally, this is different and sometimes confused with “prima facie” which simply means that the minimal amount of evidence needed to continue a case.

Timeline for Lawsuit

Malpractice lawsuits are protracted events that commonly require years to resolve. There is usually a time limit (that varies from state to state) between an untoward event and filing of a lawsuit. Typically, after a legal consultation with a plaintiff, a plaintiff's attorney will review the merits of a case with or without an outside expert. If the attorney believes there are grounds for a lawsuit, he or she prepares a summary which is presented to defendants. Because a plaintiff's attorney usually assumes all costs of litigating a case, an immediate settlement is often proposed to the defendant(s). (This strategy reduces both risk and cost to plaintiff's attorney.) If defendants disagree with contention and/or decline the proposed settlement, a lawsuit is typically initiated. Occasionally, if the lawsuit has questionable merit in the opinion of the plaintiff's attorney, it may be dropped but this is the exception rather than the rule. If the lawsuit is filed, relevant parties are deposed by plaintiff's attorney, defendants obtain their own expert witnesses who are also deposed along with plaintiff's experts and the case may subsequently go to court. Given all of the potential relevant parties involved in patient care, this process usually continues for several years. A case can be dropped or settled at any time. It is generally not in anyone's best interest to go to court.

What Is a Deposition?

A deposition is a pretrial formal testimony with a person relevant to the lawsuit that includes both plaintiff and defense attorneys as well as a court reporter. In some respects, it is a fact finding endeavor by attorneys seeking to document anything that can be used to argue the case in court. Everything that is said during a deposition is recorded and in most instances can and will be used in court. Subsequent court testimony should not differ from what has already been recorded during a deposition. There is no fixed time limit for a deposition but in my experience, most depositions last about 2 to 4 hours.

What Are the Goals of a Plaintiff's Attorney at Deposition?

There are several objectives sought by a plaintiff's attorney. In general, opposing counsel seeks to assess your potential strengths and weaknesses for trial and document your testimony. This involves thorough evaluation of your qualifications, emotional liability (i.e., ability to remain calm and collected under duress), and your own opinion of what transpired. Your own counsel is also evaluating these things and will be reluctant to place you in front of a jury if you cannot remain composed.2

Tips for Deposition

If you are the defendant in a lawsuit, remember that you are held to the standard of a “reasonable physician.” In all cases, a physician should review all relevant facts with his or her own attorney before the deposition. Your discussions with your attorney are privileged so discuss everything relevant, including any problems you may have with the care that was provided. Always follow the advice of your counsel.

Under oath, you begin by stating your name and are asked to review your background, training, board certification, and prior settlements. You will be asked to speak clearly and answer “yes” rather than “uh huh” or nod your head. Also, because the proceedings are being recorded verbatim, it is important that you allow the attorney to finish his or her question before answering, even if you know what they are going to say (Table 1). Initially, the plaintiff's attorney will review your curriculum vitae and may ask questions about anything related and relevant to the case. You may be asked whether there are any “definitive” sources of information, such as text books or particular journals. Remember that sources are usually informative and well respected but none are “authoritative.” For example, any particular journal will almost always have articles which contradict each other and many that differ from your own practice. In most cases, your own practice will be based on your training, experience, and selected information from multiple sources.

Table 1. Deposition tips.

| 1. Remain calm at all times |

| 2. Listen carefully and pause before answering all questions |

| 3. If you don't understand a question, ask for it to be repeated or clarified |

| 4. Don't guess unless advised to do so by your attorney |

| 5. Remember that there are no true definitive, authoritative sources in medicine |

| 6. Don't simply agree to plaintiff's leading questions. Reply, “not exactly, would you like me to explain?” |

| 7. “I can't remember” is a perfectly acceptable answer |

| 8. If you need one, ask for a break |

| 9. Never blame another physician (“That is outside my area of expertise; I have no opinion on that”) |

A plaintiff's attorney will ask questions intended to strengthen his or her position and attempt to establish that medical malpractice occurred. Leading questions are common and it is important to reflect briefly before addressing questions. A short pause before answering enables you to collect your thoughts and allows your attorney an opportunity to contest inappropriate questions. You may ask to have a question repeated or take a break if you need one. Avoid simply answering “yes” or “no” except to your attorney. Instead, when appropriate, answer “not exactly” or “I cannot answer that question with a mere 'yes or no' answer; would you like me to explain?” then elaborate the truth in proper context. Be succinct when possible and do not offer any more information than what is necessary to answer the question. You should not disagree simply for the sake of being contentious but sometimes a plaintiff's attorney will mischaracterize your testimony. If that occurs, simply restate the truth (“No, that is not an accurate summary of what I just said, rather…”), contradicting his or her incorrect version of your answer. Remember that a physician knows far more about medicine than a typical plaintiff's attorney and motives for asking particular questions are typically very transparent. Never guess or speculate; if you do not know the answer simply state, “I don't know” or “I can't remember.” If you need to estimate, explicitly state this although your attorney will often caution you not to estimate. You are not expected to know everything that occurred and answering, “I can't remember at this time” is an appropriate response, if accurate.

Occasionally, one of the attorneys will contest a question because it is unclear, has already been asked and answered or is otherwise unfair. You may be asked to answer it anyway (if you understand it) although it may later be declared inadmissible at trial by a judge. It is critical not to offer opinions outside your scope of expertise or blame another physician during a deposition. The statement, “That is outside my area of expertise and I have no opinion on that issue,” is perfectly acceptable. You are also not required to answer hypothetical questions; you are required to answer factual questions relevant to your involvement in the case. After the plaintiff's questioning, your attorney will briefly ask you a series of questions intended to clarify any unresolved issues to which you can typically answer “yes” or “no.” After the deposition, a transcript will be sent to you. You should check for accuracy but remember, in general, if you want to change what has already been said rather than simply correcting errors made during transcription, plaintiff's attorney may want to redepose you.

Case 1

A 35-year-old woman who had undergone laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass 10 days earlier was seen in the emergency room for abdominal pain and low-grade fever. A computed tomography (CT) scan was obtained to evaluate for an abscess with subsequent drainage requested if an abscess was found. The scan was interpreted by the radiologist as having postoperative changes but no findings suspicious for an abscess.

The patient returned home and defervesced. She was well until 1 month later when she again developed abdominal pain and fever. She returned to the emergency department but left against medical advice after waiting for several hours. The patient was contacted at home and asked to immediately return to the hospital. She deferred until morning. After awakening in the morning, she collapsed at home and died. An autopsy was performed showing a 20 cm ruptured upper abdominal abscess. A malpractice suit was brought against the radiologist for “failure to diagnose and treat a developing abscess.”

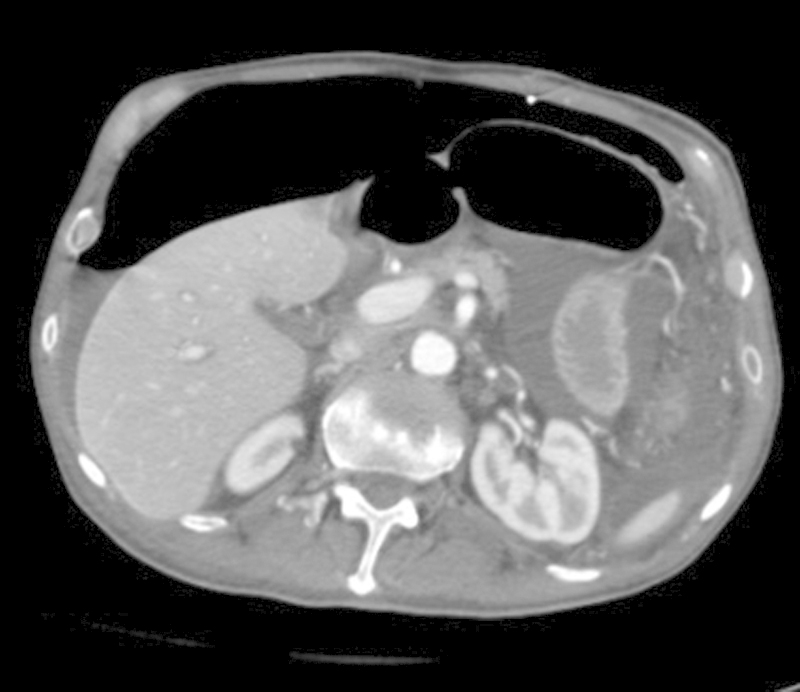

Before the deposition of plaintiff's expert witness and after reading the complaint, the defendant interventional radiologist suspected that the plaintiff's expert radiologist was unfamiliar with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. During the plaintiff's deposition, he identified the excluded gastric remnant as a “developing abscess” (Fig. 1). He was asked, “What is the normal appearance of the ‘excluded stomach’ in a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass procedure?” He replied, “I am unfamiliar with that term.” He was then asked to describe the procedure and he proceeded to describe a Roux-en-Y with a Billroth II procedure. As such, he believed that the excluded portion of the stomach, a normal finding, represented an abscess and repeatedly stated this during the deposition. This is a well-recognized pitfall that should be familiar to any expert abdominal imaging radiologist (Fig. 2).3 The defendant radiologist, experts and all other relevant parties were deposed. The case continued for a total of 5 years. The day the case was scheduled to be tried in court, the interventional radiologist was dropped from the suit and the case was settled for a small amount. It was discovered that the plaintiff's expert had been suspended by the American College of Radiology for an ethics violation after receiving a complaint regarding his expert testimony in a separate court proceeding.

Fig. 1.

Computed tomographic scan obtained 1 week after gastric bypass surgery. Note the postoperative fluid and excluded gastric remnant (white arrow) which was incorrectly described as a developing abscess by plaintiff's expert witness.

Fig. 2.

Computed tomographic scan obtained in different patient after gastric bypass. Note the excluded remnant (dashed white arrow), a normal finding which should not be confused with an abscess.

Comment

As this case demonstrates, a catastrophic outcome does not necessarily indicate malpractice and there are no qualifications for “expert witnesses.” It is interesting and sad that testimony from an expert witness, even if not factual, is admissible in court. Had the case gone to court, both the defendant and defendant's expert witness would have been required to convince the jury of the true facts of the case in light of the plaintiff's expert witness's incorrect interpretation.

Case 2

A 68-year-old man with progressive neuromuscular dysfunction and inability to eat was referred to an academic interventional radiology section for enteral feeding options. A mushroom retained G-tube was chosen as best option for long-term feeding. The procedure was initiated by an interventional radiology (IR) fellow supervised by an experienced IR attending. After 1 mg of glucagon was administered intravenously, the stomach was insufflated with a 5F catheter and the midbody of the stomach was punctured and a T-fastener deployed. After several minutes, the fellow was unable to retrogradely catheterize the esophagus and contrast was injected revealing extragastric location of the catheter. At this point, the catheter was removed and the stomach reinsufflated for repeat attempt. After reinsufflating the stomach (Fig. 3), multiple bowel loops were superimposed over the midbody of the stomach at the intended site of gastric puncture. While these were thought to represent small bowel posterior to the stomach, in light of the difficult which had already encountered, tube placement was deferred. The deployed T-tack was outside the stomach. Both fellow and attending physicians concluded that the T-tack was likely initially inadvertently deployed between the anterior abdominal wall and stomach which precipitated loss of gastric access by the 5F catheter. The procedure was terminated and the patient was admitted for overnight for observation. The patient was stable throughout without pain. The plan was for repeat attempt at gastrostomy in the morning. At 8 pm that evening, the patient began complaining of increasing abdominal pain and a CT was obtained (Fig. 4) revealing significant free intraperitoneal air. The patient was taken directly to the operating room for urgent laparotomy. A 1 cm rent was found in the stomach which was repaired primarily, a surgical G-tube was placed and there was no evidence of peritonitis. The patient made an uneventful recovery and was discharged from the hospital 1 week later. He died 16 months later and his family filed a malpractice lawsuit.

Fig. 3.

Fluoroscopic image obtained in attempted gastrostomy tube insertion. Note the T-fastener (white arrow) outside the gastric lumen. Contrast outlines the gastric fundus and multiple loops of bowel are superimposed on the midbody of the stomach.

Fig. 4.

Computed tomographic scan obtained several hours after failed gastrostomy tube insertion showing significant free intraperitoneal air. Note the T-fastener outside the stomach adjacent to the abdominal wall.

The risk management team of the hospital reviewed the case and declined to settle the lawsuit. The interventional radiologist was deposed. The expert witness for the defense was deposed. Both maintained that the complication could occur in the hands of a reasonable physician and subsequent care was appropriate. After both depositions and before disclosing their own expert witness, the case was dropped by plaintiff's attorney before disclosing her own experts.

Comment

It is unusual for a case to be dropped by plaintiff in this manner but it became apparent during depositions that this was an unusual complication that could occur in a “reasonable” physician's care which was handled expeditiously and appropriately. This does not constitute medical malpractice. The underlying complication appeared to be laceration of the anterior wall of the stomach by the T-fastener creating a 1 cm rent in the stomach. This unusual complication had been unreported at the time of the procedure but has since been noted in a recent publication.4 This is an example of a complication which could occur in virtually any patient treated by any physician. It was not immediately recognized but conservative management enabled timely diagnosis and treatment. It underlines the importance of managing a complication once it occurs; the patient was admitted, the complication was diagnosed in a reasonable time period and treated immediately. Had this not been done, the care provided would have been much more difficult to defend. A complication which could occur in any reasonable physician's hands does not constitute malpractice. However, poor management of the aforementioned complication may constitute negligence and (in my experience as an expert witness) often the focus of a lawsuit. In the author's view, with regard to the medicolegal consequences, the management of a complication is usually more important than the complication itself.

References

- 1.Carrafiello G, Floridi C, Pellegrino C. et al. Errors and malpractice in interventional radiology. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2012;33:371–375. doi: 10.1053/j.sult.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knoll J L, Resnick P J. Depositions dos and dont's: How to answer 8 tricky questions. Current Psychiatry. 2008;7:25–40. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu J, Turner M A, Cho S R. et al. Normal anatomy and complications after gastric bypass surgery: helical CT findings. Radiology. 2004;231(3):753–760. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2313030546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim J W, Song H Y, Kim K R, Shin J H, Choi E K. The one-anchor technique of gastropexy for percutaneous radiologic gastrostomy: results of 248 consecutive procedures. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2008;19(7):1048–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2008.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]