Abstract

An empirical investigation was conducted of young Palestinian, Jordanian, Israeli-Palestinian, and Israeli-Jewish children’s (N = 433; M = 5.7 years of age) cultural stereotypes and their evaluations of peer intergroup exclusion based upon a number of different factors, including being from a different country and speaking a different language. Children in this study live in a geographical region that has a history of cultural and religious tension, violence, and extreme intergroup conflict. Our findings revealed that the negative consequences of living with intergroup tension are related to the use of stereotypes. At the same time, the results for moral judgments and evaluations about excluding peers provided positive results about the young children’s inclusive views regarding peer interactions.

Keywords: stereotypes, social reasoning, moral judgments, intergroup peer exclusion, Middle-East

The Middle East is a region that has been plagued with political conflict for some time; conflict that has often spilled over into daily violence among the civilian populations living in the area. Yet, even with the recent surge in violence across the area, little research has investigated how the moral judgments and intergroup attitudes of children growing up in the Middle East have been affected by the tension and violence they are surrounded by. Most of the research on children in this area has focused on negative stereotypes held by Israeli-Jewish children and the impact negative messages received through the media have in forming these stereotypes (see Bar-Tal & Teichman, 2005). Other research focusing on Palestinian children has examined the influence of living in impoverished environments along with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder symptomotology and prevalence rates (Elbedour, Bastien, & Center, 1997; Khamis, 2005). Due to a lack of research examining the moral evaluations of intergroup relationships, the present study set out to investigate the roles that stereotypes and moral reasoning play in children’s evaluations of intergroup peer interactions involving exclusion.

The present study’s goal was to investigate social understanding in young children living in a region of the world in which violence in the community was perceived as a danger and the threat of violence was a constant reality. Our investigation focused on: (1) stereotype knowledge, children’s stereotypes about others (a Jew or an Arab); and (2) evaluations of exclusion, children’s evaluations of vignettes of peer intergroup situations involving exclusion, in which exclusion occurred for a range of reasons relating to culture and language.

It is well documented that young Israeli-Jewish (see Bar-Tal & Teichman, 2005) and Palestinian children (see Brenick, Lee-Kim, Killen, Fox, Raviv, & Leavitt, in press; Cole et al., 2003) show negative, and often extreme, stereotypes about the other. By adulthood, such extreme negative stereotyping can further the violence plaguing intercultural interactions by facilitating the dehumanization and delegitimization of the opposing group. In turn, this acts as a form of moral exclusion justifying the continued violence against the outgroup (see Bar-Tal & Teichman, 2005). While we know that children in the Middle East have stereotypes about others (see Bar-Tal & Teichman, 2005; Teichman & Zafrir, 2003), recent research (see Brenick et al., in press; Cole et al., 2003) has shown that Jewish and Palestinian preschoolers do not always apply their negative stereotypic expectations to peer encounters involving children from other cultural groups. For example, Cole et al., (2003) evaluated the effectiveness of exposure to Sesame Street (a special version of the show created for the Mid-east) on children’s stereotypes about others. The findings indicated that exposure to the program was linked to an increase in children’s use of pro-social justifications (such as friendship) when making attributions about others’ intentions (e.g., Will X push Y off the swing or ask for a turn?). What is not known from the media-based intervention research, however, is whether children, in general, apply stereotypic expectations or moral judgments to a range of peer situations involving intergroup exclusion in the absence of intervention techniques.

Yet, recent research on children’s intergroup attitudes in the U.S. has provided a theory and a methodology for investigating how children evaluate peer encounters by examining moral judgment within the context of children’s intergroup relationships (Killen, Margie, & Sinno, 2006). Findings have indicated that children use social-conventional (matters of conventions and customs), moral (matters of fairness and equality), and stereotypic knowledge to evaluate a range of peer conflict situations. Determining which forms of knowledge take priority is a central aspect of the research goal. This approach lends itself to the complexity of stereotype use to explain how the context of the intergroup situation can dictate how children use stereotypes. Further, this approach has been used to study U.S. children’s evaluations of exclusion based on gender, race, ethnicity, and social cliques (see Brenick, et al, in press; Killen, Sinno, & Margie, 2006, for reviews). No studies that we know of, however, have used this approach to investigate young children’s application of moral knowledge to peer exclusion contexts with non-U.S. samples.

For the present study, young children’s moral reasoning regarding exclusion was assessed using peer intergroup exclusion vignettes, which detailed the potential exclusions of a target child based on being from a different country, speaking a different language, or having different cultural customs. For each of the three vignettes given, young children were asked to judge whether the target child should be included or not, to rate how good or bad it would be to exclude the child, and to reason why. The present study set out to investigate how children from multiple groups in the Middle East draw on cultural stereotypes and moral reasoning when evaluating intergroup scenarios.

The present study examined issues of reasoning in four different groups of children: Israeli-Jewish, Palestinian, Israeli-Palestinian, and Jordanian. Sampling three different Arab groups of children was important for two reasons. First, little is known about Arab children’s social development. As mentioned earlier, most of the research has focused on clinical and psychological issues facing these children, such as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Given that children in this region live amidst such intense physical and psychological conflict, we must also understand Arab children’s stereotypes and intergroup social and moral reasoning and this is the first of study that we know of to include three different samples of Arab children (Israeli-Palestinian, Palestinian, and Jordanian). The three Arab groups in our study reflect a range of physical and psychological proximity to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Yet, while their direct experience with the conflict may vary youth can be affected by a conflict even when they do not come in direct contact with the violence (Slone, 2003). Second, like all cultures, the Arab culture is heterogeneous, varied, and multifaceted. The cultural environment of children affords a range of gender and family relations which reflect recent changes taking place in new socio-economic contexts (Alsoudi & Mahdi, 2004; Hopkins, 2001; Tibi, 1990). Yet, assumptions of homogeneity of culture are frequently attributed to pan-Arab societies. Social psychologists have documented the “outgroup homogeneity effect” in which individuals understand heterogeneity of the ingroup but assume homogeneity of the outgroup (Judd & Park, 1993). This phenomenon may also apply when individuals in one culture make attributions about another culture (e.g., when Americans assume that all “Arab” cultures, or all “Asian” cultures, are of one type). Social psychologists theorize that the outgroup homogeneity effect frequently leads to stereotyping given that stereotyping also involves ignoring intragroup variation. Thus, by including three diverse Arab cultural groups in this project, we can fully examine within-culture variability to determine what aspects of social and moral judgments underlie diverse cultures and what aspects of evaluations of exclusion may be unique to one particular group.

To expand this further, we sampled two Israeli groups, Israeli-Palestinian, and Israeli-Jewish to focus attention, again, on the diversity of samples within one cultural group (in this case, Israelis). The Israeli-Palestinian group belongs to both Israeli and Arab culture, and this biculturalism reflects an important category of group membership in the Middle East rarely studied in empirical developmental research. Yet, we did not design the study to control for all societal factors, such as socioeconomic factors, given the absence of particular groups (e.g., middle-income Palestinians) and the fact that we were given the opportunity to collect these data as part of a larger evaluation project of the influence of viewing Sesame Stories, a public television program broadcasted to the groups of children in this study subsequent to the data collection conducted for this project (which served as the pre-test or baseline data for the media intervention evaluation project). Nonetheless, a wide sampling of the ecologically valid cultural groups was utilized in this study.

Hypotheses

We predicted that young children, in general, would have negative stereotypes about the outgroup based on research conducted with Arab and Israeli children in Israel (Bar-Tal & Teichman, 2005; Cole et al., 2003; Teichman & Zafrir, 2003). We also predicted variability within our three Arab samples. First, we predicted that Palestinian children would have the most negative stereotypes due to the high-stress conflict experienced by Palestinian children and families, their insular existence confined to limited travel, and the negative contact they frequently have with Israelis found through check-points and the like (rather than everyday interactions in schools). Second, we expected that Jordanian children would also have negative stereotypes due to the limited contact they have with Israeli-Jewish children. Israeli-Palestinian children, however, have more frequent and varied contact with this particular outgroup, and thus we predicted that they would have fewer negative stereotypes than the other two Arab samples. It should be noted that this remained an open question, as the contact that Israeli-Palestinian children have with Israeli-Jewish children can vary between positive and negative interactions due to the constantly changing political climate.

Finally, we predicted that Israeli-Jewish children would also hold negative stereotypes due to the wealth of research that has been conducted on the stereotypes of Israeli-Jewish children which has found a bombardment of negative messages about Arab groups in the media and in textbooks (Bar-Tal & Teichman, 2005). It follows that from a young age Israeli-Jewish children have been found to hold negative stereotypes toward Arabs in terms of their general attributes, and occupations, and this has, in turn, shaped their desire for contact with them (Bar-Tal & Teichman, 2005; Cole et al., 2003). It stands to reason then that they, too, would hold negative stereotypes toward the outgroup in the present study.

When looking at children’s judgments and reasoning regarding exclusion in peer encounters, we expected, overall, that all children would vary in which types of exclusion they viewed as legitimate, and this could depend, in part, on social-conventional norms in their own cultures. We expected that exclusion based on the cultural reason of being from a different country would be most pronounced for the Palestinian children living in Ramallah given the political issue of country for them, as well as the lack of mobility of the families that these children come from. For all four groups we expected exclusion based on different country to yield the greatest level of support followed by exclusion based on customs and different language.

In addition to analyzing children’s judgments (“Should include or should not include?”) and ratings (“How good or bad is it to exclude?”) about exclusion, we analyzed their justifications (“Why?”). Our expectations were that children’s justifications for rejecting exclusion would stem from moral reasons, such as unfairness. In contrast, children’s reasons for accepting exclusion would stem from social-conventional reasons, and to a lesser extent, stereotypes. We predicted that social-conventional justifications about group functioning would form the basis for children’s decisions to accept exclusion based on cultural customs and different language, and that stereotypic justifications about members of other cultures would be used to accept exclusion in the context of different country memberships given the strength of stereotypes about others as documented by Bar-Tal and colleagues (Bar-Tal & Teichman, 2005).

Methodology

Participants

Participants were 433 preschool and kindergarten children (M = 5.7 years, SD = .34, range 4.4 - 6.7-years) nearly evenly divided by gender and cultural group. Children were recruited from four sites in the Middle-East. Two of the sites were in Israel: one with a sample of Israeli-Jewish children in Tel-Aviv (N = 102, M = 5.7-years, SD = .30), and a second with Israeli-Palestinian children in Nazareth, Kufur Qari, and Baka Elgarbia (N = 119, M = 5.9-years, SD = .29). Two other sites were located in the West Bank with a sample of Palestinian children in Ramallah (N = 100, M = 5.6-years, SD = .30), and in Jordan with a sample of Jordanian children residing in Amman (N = 112, M = 5.7-years, SD = .40). The Israeli-Jewish and the Jordanian samples were middle-income. The Israeli-Palestinian sample was middle-to-low income. The Palestinian sample was low-income.

Procedure

Trained research assistants, matched to each child’s ethnicity, individually interviewed each child in his or her own language. They used the instrument accompanied by scale and picture cards. There were separate versions of the interview for male and female children, and the names used in the vignettes were matched to the gender and cultural group of the participant. The interviewer first administered a warm-up task that consisted of showing children a picture of an ice cream cone and asking them to point to the place on a 4- point smiley/frown faces scale card that represents how much they like ice cream. This was done to familiarize the children with the interviewer as well as the scale card that would be used throughout the interview. Following the warm-up task, first, a stereotype knowledge assessment was administered in which children were asked to identify and describe child members of the outgroup (Arabs or Jews). Next, children were asked to evaluate the three peer exclusion vignettes.

Design and Measures

Research assistants recorded children’s responses verbatim which were subsequently translated into English. To ensure veridicality of translations, a subset of responses was back-translated (English into Arabic or Hebrew) and compared to the original responses. Information from pilot testing was utilized to develop the coding and analysis plan as described below. This project was part of a larger pre-test/post-test study commissioned by Sesame Workshop. Only the pre-test data are presented in this paper.

Interview Instrument

The instrument was comprised of 2 sections: (1) Stereotype Knowledge, which assessed the children’s stereotypes about the other group, and (2) Evaluations of Exclusion, which assessed the children’s evaluations about intergroup conflict vignettes. The first section asked children questions about their views of the “other” (e.g., Israeli-Jewish children were asked about Arabs and Arab children were asked about Jews). The second section presented vignettes involving dilemmas of conflict resolution and stereotyping which are described in more detail below. Vignettes used in the instrument were chosen based on ecological relevance; each detailed hypothetical situations that children of this region could relate to. They match the context of the TV show that was constructed by local producers in the Middle East as well as the age group targeted for the TV show. The instrument was originally developed in English, translated into both Hebrew and Arabic and then back-translated into English to ensure consistency across translations. Prior to administration, the instrument was extensively pilot-tested to verify that children in the different settings understood the interview questions.

Children’s stereotype knowledge. To assess children’s knowledge about the outgroup, children were presented with a picture of an Arab or Jewish child who matched their gender and asked whether they were familiar with the child (“Do you know what (Arab / Jew) is?”). Israeli-Jewish children were presented with a picture of an Arab child, whereas Israeli-Palestinian, Jordanian, and Palestinian children were presented with a picture of a Jewish child. Next, if the participant responded in the affirmative, that they knew of an Arab or Jewish child, depending on their cultural group membership, they were asked, “What is an Arab/ Jew?”. Children’s answers were recorded and subsequently translated into English and coded.

Children’s exclusion evaluations. In this section, children’s exclusion reasoning was assessed. Children were asked to evaluate three vignettes. The vignettes depicted situations of peer conflict with regard to exclusion. For each vignette children were first asked to make a judgment (e.g., “Should the group include or not include the child?”), and a rating (e.g. “How good or bad is it to exclude the child”), and were then asked to explain their judgment, referred to as justification (e.g., “Why is it okay or not okay to exclude?”), a methodology adapted from standard protocols used in the social and moral development literature (see Killen, McGlothlin, & Lee-Kim, 2002; Smetana, 1995, 2005; Turiel, 1983, 2005). An interviewer presented each vignette to the child being interviewed using both a series of cartoon drawings and verbal descriptions of the initial action.

The vignettes used in this instrument involved everyday scenarios with peers, however, these vignettes focused on issues of exclusion (based on cultural membership), inclusion (regarding societal conventions, and language barriers), and stereotypes. There were three vignettes in total. The first vignette, entitled, “Different Country”, involved a group of good friends that had to decide whether they should play with a child from a different country. The vignette referred to as “Cultural Custom,” dealt with a group of friends who planned a party to which everyone had to wear the same party hat and whether they should let another child come to the party even though the child came from another country where they only wore a different type of party hat. Last, the “Different Language” vignette featured a group of children who all spoke the same language and whether they should first stop and help another child who spoke a different language and had fallen while they were running to the ice cream truck and then get their ice cream or if they should first get their ice cream and then help the child.

Coding and Coding Categories

Children’s Stereotype Knowledge responses (“What is a Jew/Arab?” “What are Jews/Arabs like?”) were coded using an established set of coding categories divided according to negative, positive, and neutral attributes (examples below) used in a prior study (Cole et al., 2003). For the peer intergroup exclusion vignettes, children’s judgment responses of “should exclude” received a 0 and responses of “should not exclude” received a 1 (see Smetana, 1995, for details about coding). Justification responses were coded according to a range of conceptually-based categories that were developed using a standard protocol which encompassed moral (e.g., “fairness,” “inclusion,” “prosocial”), social conventional (e.g., “cultural stereotypes,” “group functioning”), and personal (e.g., “personal choice,” “selfish motives”) justifications (see Appendix A for description of justifications coding categories). These systems were developed based on a sampling of the children’s open-ended justification responses across all cultural groups, and were derived from the social-cognitive domain model and previous research using related categories (see Killen et al., 2002; Smetana & Asquith, 1994; Turiel, 1983, 1998).

Reliability

Reliability coding was calculated on the justification data for both stereotype knowledge and exclusion evaluation assessments on 15% of the interviews. Using Cohen’s kappa, inter-rater agreement in scoring overall responses was .93 and percent agreement between coders was 92% for both sets of justification data.

Results

Plan of Analysis

Children’s stereotype responses were scored as proportions of negative, positive, and neutral categories. Children’s exclusion judgments were scored as proportions of inclusive responses while their exclusion ratings were mean responses from the 4-point Likert scale of how good or bad it is to exclude the target child (1 = very bad, 4 = very good). Children’s exclusion reasoning responses were proportions of cultural stereotypes, selfish motives, fairness, group functioning, personal choice, prosocial mandates, friendship and inclusion categories and were treated as a repeated measures within-subject variable (see Appendix A for description of coding categories). For these assessments, we conducted repeated measures ANOVAs with follow-up post-hoc Bonferroni comparisons for cultural group, paired t-tests for within-subject effects and follow-up univariate ANOVAs to test between-subjects effects. Researchers using a social-cognitive domain approach to analyzing categorical judgment and justification data have successfully used similar data analysis procedures in their studies (see Killen et al., 2002; Nucci, & Killen, & Smetana, 1996; Smetana, 1986; Tisak, 1995; Turiel, 1998). For all ANOVAs conducted, in cases where assumption of sphericity was not met, corrections were made using the Huynh-Feldt method.

Children’s Stereotypes

Stereotype Knowledge

Children were asked whether they had knowledge of the outgroup (Arab, Jew). Means analysis revealed that overall, a majority of children (M = .74, SD = .44) responded positively (“yes”) that they had knowledge of an Arab or a Jew.

In order to assess children’s stereotype knowledge responses, a 2 (gender of participant) x 4 (Cultural Group: Israeli-Jewish, Israeli-Palestinian, Jordanian, Palestinian) x 3 (attribute: negative, neutral, positive) ANOVA with repeated measures on the last factor was conducted on participant responses to “What is an Arab/Jew?”. Results for this question revealed interaction effects for Attribute x Cultural Group, F (6, 850) = 33.79, p < .001, ηp2 = .19 and Attribute x Gender, F (2, 850) = 16.53, p < .001, ηp2 = .04. Although overall, children’s negative, neutral, and positive responses did not differ, closer examination of Attribute x Cultural Group revealed differences between Israeli-Jewish, Israeli-Palestinian, Jordanian, and Palestinian children supporting our hypotheses.

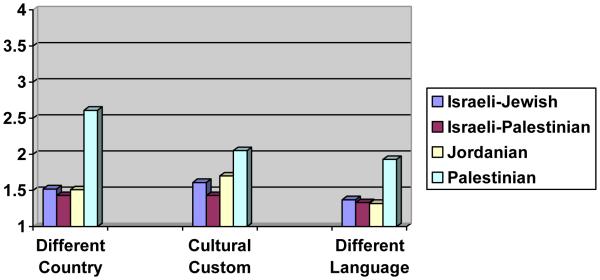

As shown in Figure 1, Israeli-Jewish children were more likely to provide neutral attributes than either negative, p < .001, or positive, p < .04, (Ms (SD)s = .53 (.50), .13 (.34), .34 (.48), respectively) attributes in their responses. Examples of neutral attributes given by children include “people work for them”, “they drive cars and have money”, and “Arabic is a language”. Israeli-Palestinian children were more likely to provide positive descriptions of the outgroup than negative or neutral attributes, (Ms (SD)s = .58 (.50), .08 (.26), .30 (.46), respectively), ps < .001, while both Palestinian and Jordanian children were more likely to provide negative attributes than the neutral and positive attributes, ps < .001 (Ms (SD)s = Palestinian: .48 (.50), .06 (.24), .04 (.20); Jordanian: .48 (.50), .26 (.44), .07 (.26), respectively). Examples of positive attributes include “I know about good Arabs”, “Arabs are like Jews”. Some examples of negative responses given include “Shoots soldiers”, “They are black and not good”, and “Someone bad”. Closer examination of gender differences revealed that boys were least likely to provide neutral responses compared to negative, p < .003, or positive responses, p < .001(Ms (SD)s = .17 (.38), .33 (.47), .31 (.46), respectively), while the reverse pattern was observed in girls, as neutral attributes were given more than positive, p < .001, or negative attributes, p < .002 (Ms (SD)s = .41 (.49), .23 (.42), .24 (.43), respectively).

Figure 1.

Proportions of Negative, Neutral, and Positive Attributes Given in Response to the Question “What is an Arab/Jew?” by Culture

Note. N = 433. Proportions cannot exceed 1.00.

In addition, between-subjects effects for Cultural Group were found for responses to the stereotype knowledge question, F (3, 425) = 32.46, p < .001, ηp2 = .19. Follow-up analyses revealed that in response to “What is an Arab/Jew?”, Palestinian and Jordanian children were more likely to provide negative attributes than Israeli-Jewish or Israeli-Palestinian children when asked to describe the outgroup, ps < .001, (Ms (SD)s = .48 (.50), .48 (.50), .13 (.34), .08 (.26), respectively). Neutral responses were provided significantly more by Israeli-Jewish children (M = .53, SD = .50) and significantly less by Palestinian children (M = .60, SD = .24) than Israeli-Palestinian (M = .30, SD = .46) and Jordanian children (M = .26, SD = .44), p < .001.

Children’s Moral Reasoning about Peer Exclusion

Overview

In this section, analyses were conducted on children’s responses to three exclusion vignettes: Exclusion based on Different Country, Cultural Custom, and Different Language. Analyses were conducted for children’s: (1) Exclusion Judgment, (2) Exclusion Rating, and (3) Exclusion Reasoning. For exclusion judgment and exclusion rating assessments, 2 (gender of participant) x 4 (cultural group) ANOVAs were conducted. For exclusion reasoning analyses, 2 (gender of participant) x 4 (cultural group) x repeated measures ANOVAs were conducted on justification categories meeting a frequency criteria greater or equal to .10 for each vignette. The exclusion vignette results are presented in order of increasing complexity of the scenarios.

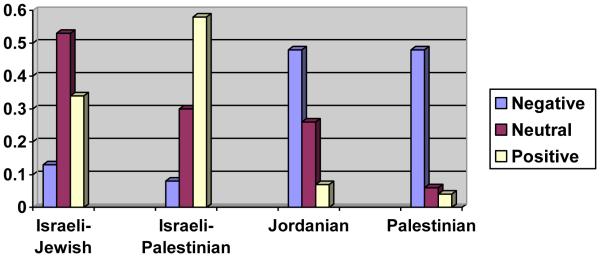

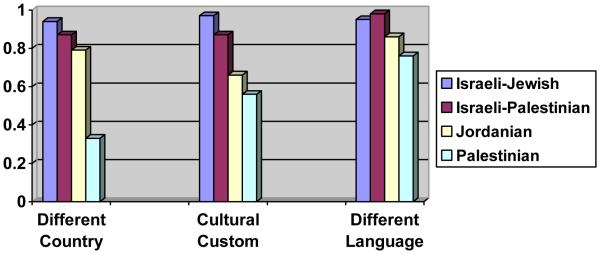

Different Country

Analyses were conducted on children’s evaluations of a vignette in which a group of children could exclude a child from a different country. Results examining children’s exclusion judgment revealed a main effect for Cultural Group, F (3, 403) = 47.97, p < .001, ηp2 = .26. When asked to decide whether the group should or should not exclude the new child from a different country, Israeli-Jewish children (M = .94, SD = .24), were more likely to reject exclusion than Palestinian, (M = .33, SD = .47), p < .001, or Jordanian children, (M = .79, SD = .41), p < .01 (see Figure 2). In contrast, Palestinian children were more likely than the other cultural groups to judge exclusion as all right, (Israeli-Palestinian, M = .87, SD = .34), ps < .001. Similar to judgment results, a main effect for Cultural Group, F (3, 420) = 42.81, p < .001, ηp2 = .23, was found for children’s exclusion ratings. As shown in Figure 3, Palestinian children were more likely to support a group’s decision to not play with a child from a different country than Israeli-Jewish, Israeli-Palestinian, or Jordanian children, (Ms (SD)s = 2.61 (1.07), 1.52 (.79), 1.43 (.80), 1.51 (.75), respectively), ps < .001.

Figure 2.

Proportion of Positive Judgments about Inclusion by Culture

Note. N = 433. For Exclusion Vignettes: Should the group include or not include the child? Rating: 0 = not included, 1 = included. Proportions cannot exceed 1.00.

Figure 3.

Mean Ratings of “All right to Exclude” by Culture

Note. N = 433. For Exclusion Vignettes: Is it all right to exclude? Rating: 1 = Not good to 4 = Yes, good.

Exclusion reasoning. Examination of children’s justifications for why the group should or should not exclude the child from a different country revealed a main effect for Justification, F (34.64, 1972.91) = 38.48, p < .001, ηp2 = .08, and an interaction effect for Justification x Cultural Group, F (13.93, 1972.91) = 14.45, p < .001, ηp2 = .09. Included in analyses were five justifications: Stereotype, Fairness, Prosocial, Friendship, and Inclusion (see Appendix A for description of categories). As expected, children’s reasoning involved multiple considerations. Overall, children were more likely to refer to Inclusion (M = .25, SD = .44), Friendship (M = .21, SD = .41), and Stereotypes (M = .19, SD = .40) justifications than Fairness (M = .08, SD = .28) or Prosocial (M = .10, SD = .30) justifications, ps < .001, when asked to provide a reason for their judgment to exclude or not exclude. In follow-up analyses, a similar pattern of results was found to vary by cultural group.

As shown in Table 1, Israeli-Jewish, Israeli-Palestinian and Jordanian children made more references to Inclusion and Friendship justifications than other types of reasoning. While Israeli-Jewish children were more likely to appeal to inclusiveness and friendship than maintenance of stereotypes, ps < .001 or fairness, ps < .02, Israeli-Palestinian children used more Inclusion and Friendship reasoning than Stereotype, ps < .05, .01, Prosocial, ps < .02, .001, or Fairness, ps < .03, .001, reasoning when asked to evaluate whether the group should exclude the child from a different country. As well, Jordanian children were also more likely to appeal to Inclusion than Stereotype, Fairness, and Prosocial, ps < .001, or Friendship, p < .01 reasons. They also used made more references to promoting Friendship than Prosocial, p < .03, or Stereotype and Fairness concerns, ps < .01. In contrast, Palestinian children were more likely to use Stereotypes than all other types of reasoning, ps < .001, to justify their evaluation of excluding the child from another country (see Table 1 for all means). For example, when asked why the group should let the boy from a different country play with them, one child appealed to inclusion by responding, “Because we should be friendly to everybody and not refuse playing with them. It doesn’t matter where she is from” (Israeli-Palestinian child), while another child referred to friendship as a reason for inclusion, “Because it doesn’t matter if he is an Arab, you can get to know him and then become his friend” (Israeli-Jewish child). In support of exclusion, some children used cultural stereotypes in their responses, “If he was a Jewish boy, they shouldn’t let them play, but if he was from their country, they should let him play,” (Palestinian child) and “Because it is their swing and it’s not his house or his country” (Jordanian child). As can be seen from these examples of children’s responses, different types of concerns were reflected in the reasoning used to evaluate this type of exclusion.

Table 1.

Proportions of Justifications for Different Cultural Exclusion Vignettes by Culture

| Vignette by Culture | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||||

| Different Country | Cultural Custom | Different Language | ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| I-J | I-P | Pal | Jor | I-J | I-P | Pal | Jor | I-J | I-P | Pal | Jor | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

| Justification |

M

(SD) |

M

(SD) |

M

(SD) |

M

(SD) |

M

(SD) |

M

(SD) |

M

(SD) |

M

(SD) |

M

(SD) |

M

(SD) |

M

(SD) |

M

(SD) |

| Stereotype | 0.05 (0.22) |

0.13 (0.33) |

0.58 (0.50) |

0.05 (0.23) |

0.00 (0.00) |

0.03 (0.16) |

0.00 (0.00) |

0.04 (0.19) |

0.00 (0.00) |

0.02 (0.13) |

0.21 (0.41) |

0.01 (0.09) |

| Fairness | 0.12 (0.32) |

0.12 (0.32) |

0.04 (0.20) |

0.05 (0.23) |

0.10 (0.30) |

0.08 (0.26) |

0.06 (0.24) |

0.02 (0.13) |

0.66 (0.48) |

0.76 (0.43) |

0.61 (0.49) |

0.58 (0.50) |

| Group Functioning | 0.01 (0.10) |

0.04 (0.20) |

0.02 (0.14) |

0.11 (0.31) |

0.08 (0.27) |

0.17 (0.37) |

0.39 (0.49) |

0.28 (0.45) |

0.01 (0.10) |

0.01 (0.09) |

0.00 (0.00) |

0.01 (0.09) |

| Prosocial | 0.15 (0.36) |

0.11 (0.31) |

0.05 (0.22) |

0.09 (0.29) |

0.15 (0.36) |

0.11 (0.31) |

0.08 (0.27) |

0.11 (0.31) |

0.12 (0.32) |

0.08 (0.28) |

0.02 (0.14) |

0.17 (0.38) |

| Friendship | 0.25 (0.43) |

0.29 (0.46) |

0.10 (0.30) |

0.20 (0.40) |

0.05 (0.22) |

0.15 (0.36) |

0.04 (0.20) |

0.08 (0.27) |

0.11 (0.31) |

0.06 (0.24) |

0.04 (0.20) |

0.10 (0.30) |

| Inclusion | 0.30 (0.46) |

0.23 (0.42) |

0.07 (0.26) |

0.39 (0.49) |

0.54 (0.50) |

0.41 (0.49) |

0.28 (0.45) |

0.39 (0.49) |

0.02 (0.14) |

0.03 (0.16) |

0.03 (0.17) |

0.05 (0.23) |

Note. N = 433. Proportions cannot exceed 1.00. 1-J = Israeli-Jewish; I-P = Israeli-Palestinian; Pal = Palestinian; Jor = Jordanian. M = Mean, SD = Standard deviation.

Cultural Custom

Children were asked to evaluate a vignette in which a group planning a party could exclude a child from a different country where different hats are worn to the party. Analysis of children’s judgments revealed main effects for Cultural Group, F (3, 403) = 20.20, p < .001, ηp2 = .13, and Gender, F (1, 403) = 47.97, p < .04, ηp2 = .01. In response to whether the group with one type of party hat should or should not let the child with the different party hat join them, Israeli-Jewish children (M = .97, SD = .17) and Israeli-Palestinian (M = .87, SD = .34), children were more likely to reject exclusion than Jordanian (M = .66, SD = .48), or Palestinian children (M = .56, SD = .50), ps < .001, (see Figure 2). Analysis of gender differences revealed boys (M = .82, SD = .39) were slightly less likely to support exclusion than girls (M = .74, SD = .44), p < .04. When asked to rate the degree to which it would be wrong to exclude the child with the different party hat, results from children’s exclusion ratings revealed a main effect for Cultural Group, F (3, 420) = 8.34, p < .001, ηp2 = .06. As shown in Figure 3, although most children viewed exclusion as being wrong, Palestinian children were more likely than Israeli-Jewish, p < .01, Israeli-Palestinian, p < .001 or Jordanian, p < .02, children to rate exclusion in a positive direction (Ms (SD)s = 2.05 (.98), 1.61 (.81), 1.43 (.81), .170 (.94), respectively).

Exclusion reasoning. Examination of children’s reasoning about whether a group should or should not exclude the child with the different party hat confirmed expectations that children’s responses would reflect multiple considerations with regards to the group and the individual. Results revealed a main effect for Justification, F (3.45, 1465.24) = 89.41, p < .001, ηp2 = .17, and an interaction effect for Justification x Cultural Group, F (10.34, 1465.24) = 5.41, p < .001, ηp2 = .04. Included in analyses were four justification categories, Group Functioning, Prosocial, Friendship, and Inclusion. Overall, children were more likely to appeal to Inclusion (M = .41, SD = .49) than other types of reasoning: Group Functioning (M = .23, SD = .42), Prosocial (M = .11, SD = .31), or Friendship (M = .08, SD = .28), ps < .001. In addition, Group Functioning (M = .23, SD = .42) was used significantly more often than Prosocial (M = .11, SD = .31) or Friendship (M = .08, SD = .28) reasons when evaluating whether the group should let the child with the different hat join their party. Similar results were found when examining cultural group differences in reasoning. While Israeli-Jewish and Israeli-Palestinian children were more likely to make references to Inclusion than to other types of reasoning, ps < .001, when evaluating exclusion, Palestinian and Jordanian children used both Inclusion and Group Functioning reasons significantly more often than the other two types of reasoning, Prosocial, ps < .001, and Friendship, ps < .001 (see Table 1 for all means). As an example, some children’s responses reflected Inclusion reasoning: “Even if her hat is striped, they should let her share in the party” (Jordanian child), and “They have to include him because it doesn’t matter what color are the hats” (Israeli-Jewish child), while others expressed concern for group functioning, “Because she has a striped hat and you have to have a dotted hat to join the party” (Israeli-Palestinian child), and “The party is for those who have the dotted hats not like his hat” (Jordanian child). These examples show the variability in reasoning within cultural groups. In particular, for Palestinian and Jordanian children, although their exclusion judgments were less supportive of inclusion than Israeli-Jewish or Israeli-Palestinian children, some children appealed to Inclusion while others expressed concern for preserving Group Functioning.

Different Language

Children were asked to evaluate a vignette in which a group of children could stop to assist an injured child who speaks a different language prior to or subsequent to getting ice cream. Analysis on children’s judgments revealed a main effect for Cultural Group, F (3, 403) = 10.51, p < .001, ηp2 = .07. As shown in Figure 2, although overall, a majority of children’s responses were positive, Palestinian children were least likely to respond that the group should assist the child prior to getting ice cream than Jordanian, Israeli-Jewish, or Israeli-Palestinian children, ps < .001 (Ms (SD)s = .76 (.43), .86 (.34), .95 (.22), .98 (.26), respectively). When asked to rate the degree to which it would be wrong to assist the child after the group got their ice cream, examination of children’s exclusion ratings revealed a main effect for Cultural Group, F (3, 420) = 16.45, p < .001, ηp2 = .11. As shown in Figure 3, similar to judgment results, although most children viewed waiting to help the injured child as wrong, Palestinian children (M = 1.93, SD = .98), were more likely than the other cultural groups to rate the group’s delay of assisting the child in a positive direction, ps < .001 (Ms (SD)s = Israeli-Jewish: 1.37 (.54), Israeli-Palestinian: 1.33 (.73), Jordanian: 1.32 (.61)).

Exclusion reasoning. Analysis of children’s reasoning about whether the group should immediately assist or delay helping the injured child revealed a main effect for Justification, F (2.7, 1147.68) = 309.67, p < .001, ηp2 = .42, and a Justification x Cultural Group interaction, F (8.10, 1147.68) = 4.92, p < .001, ηp2 = .03. Included in analyses were three justification categories, Stereotype, Fairness, and Prosocial. Overall, children appealed to Fairness (M = .66, SD = .48) more significantly than Stereotype (M = .06, SD = .23) or Prosocial (M = .10, SD = .30) reasoning, ps < .001. Closer examination of cultural group differences revealed that all groups did not differ in their use of Fairness reasoning. Palestinian, Jordanian, Israeli-Jewish and Israeli-Palestinian children were all more likely to view the group’s actions towards the injured child from a moral viewpoint (Fairness) than from a perspective involving Stereotype or Prosocial concerns, ps < .001 (see Table 1 for means). As an example, some children said, “Because she is much more important than the ice cream and they should help her, whenever they hear her call for help” (Israeli-Palestinian child), “Because a human being is more important than ice cream and ice cream you can buy anywhere” (Israeli-Jewish child), “He shouldn’t be left alone when he’s wounded. They should help him and afterwards, they can run together to get ice cream” (Palestinian child) and “They should help him even if he doesn’t speak Arabic and say sorry to him” (Jordanian child). A few other differences were found. While Israeli-Jewish children did not make any references to Stereotypes compared to other types of justifications, ps < .001, Palestinian children did use Stereotypes reasoning more significantly than Prosocial reasoning, p < .001, when evaluating whether the group should immediately help the injured child who spoke a different language (see Table 1 for all means).

Discussion

The aim of this project was to investigate young children’s stereotyped concepts about members of an outgroup (in this study, an Arab and a Jew), with four samples of children living in the Middle East who differed in their cultural backgrounds. We analyzed children’s social and moral reasoning about peer inclusion and exclusion based upon a number of different factors. These data enabled us to compare children’s stereotypes with their moral judgments about peer exclusion. This study was unique with its focus on four groups of children, Palestinian, Jordanian, Israeli-Palestinian, and Israeli-Jewish, living in one geographical region that has a history of cultural and religious tension, violence, and extreme intergroup conflict. Moreover, it is the first study, to our knowledge, that included three subgroups of Arab children in an empirical investigation of social judgment. This unique sample enabled us to report heterogeneity within Arab cultures regarding young children’s stereotypes, moral judgments, and evaluations of exclusion. Our findings were both reflective of the negative consequences of living with intergroup tension and hopeful about the next generation’s positive moral perspective, along with their overall rejection of peer group exclusion based on language, culture, and country. Further, our results provide new information about young children’s moral judgments in the context of intergroup contexts in the absence of a media-based intervention to promote prosocial judgments (see Cole, et al., 2003).

Stereotyping the Other

While our findings for children’s stereotyping confirmed Bar-Tal and Teichman’s research (Bar-Tal & Teichman, 2005) which has demonstrated that Jewish children hold negative stereotypes about Arabs, and that Arab children hold negative stereotypes about Jews, overall, the children in the current study provided a mix of positive, negative and neutral attributes. When we asked children to respond to: “What is an Arab/Jew?” Israeli-Palestinian children were more likely to use positive attributes than negative attributes, while Israeli-Jewish children used primarily neutral attributes, and Palestinian and Jordanian children used mostly negative attributes. When asked: “What are Arabs/Jews like?”, again, children provided a combination of positive, negative and neutral responses. There were both cultural and gender differences as well. Israeli-Palestinian children were more likely to use neutral or positive than negative attributes, Israeli-Jewish children were more likely to use neutral attributes, and Palestinian and Jordanian children were more likely to give neutral or negative responses than positive ones for the assessment “What are Arabs/Jews like?”.

What was surprising, however, was that Palestinian and Jordanian children gave positive and neutral responses (in addition to negative ones) to these probes about the other. Given the historical and current tensions in the region, one might predict that young children would only rely on negative stereotypes to describe a Jewish person. In contrast, there was a mixture of attributes associated with someone from the Jewish culture. Moreover, boys were somewhat more likely to give negative responses than were girls. These findings provide a more complex picture of children’s stereotypes than has been previously documented. While some children clearly associated negative traits with members of the outgroup, more children than we expected, given prior research findings, associated positive or neutral traits with pictures of the other.

One possible reason for these differences could be due to the methodological differences between our measure and that used by researchers in the field (Bar-Tal & Teichman, 2005). In the present study, we showed children picture cards of another child member of the outgroup. Bar-Tal and colleagues (2005) showed children a picture card of an adult member of the outgroup. Our exclusion vignettes involved children rather than adults, and thus we used child picture cards in the stereotype assessment to allow us to compare stereotypes about others with moral judgments and moral reasoning about others in peer conflict scenarios. In essence, we controlled for the adult/child status of the target by depicting children in all of our stimuli. What we found was that children’s attributions of negative stereotypes to pictures of children were slightly less than to pictures of an adult, which is to be expected given that adult members of the outgroup typify the stereotype.

Moreover, our approach differed from the standard prejudice measures with children, which ask children to assign a trait to an individual based on the picture card depicting an ingroup and outgroup member, and typically as a function of race or ethnicity (Aboud & Levy, 2000). For example, this would entail asking children, “Who is dirty, an Arab or a Jew or both?” We did not suggest traits to children; instead we asked children for their spontaneous knowledge about the other, and for their spontaneous associations. Children did not hesitate to tell us negative traits, indicating that social desirability pressures were not an issue in this project. At the same time, our assessment revealed positive and neutral traits as well providing a full picture of children’s spontaneous associations with members of the outgroup.

Evaluations of Peer Exclusion

Children evaluated three peer exclusion situations, exclusion based on different country, cultural custom, and different language. These vignettes reflected a range of societal and conventional considerations. We expected that children living in the Middle East would be most willing to support a group’s decision to exclude a child from a different country, followed by customs and different language. These expectations were based on prior results in the U.S. which have demonstrated that exclusion situations which entail conventional considerations such as cultural norms and issues pertaining to group functioning are more likely to invoke children’s exclusion rather than inclusion responses (Killen, Lee-Kim, McGlothlin, & Stangor, 2002). We had three different dependent measures, which informed us about different facets of children’s evaluations of peer exclusion: judgments (to exclude or not), ratings (how bad is it to exclude?) and justifications (reasons for judgments).

Culture as a Basis for Exclusion

There was variability in how children responded to exclusion based on cultural membership, and this basis for exclusion was analyzed in three ways: different country, different language, and cultural custom. All groups of children viewed it as wrong to exclude in the Different Language vignette. Children gave priority to helping an injured child who spoke a different language. Further, most children used empathy as a form of moral reasoning to support assisting others regardless of a cultural difference based on language. For the Palestinian children, only a minority used stereotypes to justify exclusion of someone who speaks a different language.

These findings confirm social-cognitive domain theory about the generalizability and universality of moral judgments, and particularly so for young children (Smetana, 2006; Wainryb, 2006). Children living in a dangerous region of the world, with constant societal tensions, judged refusing to help an injured child as wrong, and that it is wrong due to the lack of empathy that would result in ignoring the child. Further, our cultural groups reflected both “individualistic” and “collectivistic” communities, and yet, there were few differences among children regarding the wrongfulness of exclusion in this context (Wainryb, 2006).

There was greater variability among the groups of children regarding evaluations of exclusion based on different country and cultural customs. Whereas the Israeli-Jewish, Israeli-Palestinian, and Jordanian children viewed it as wrong to exclude for these dimensions of culture, Palestinian children viewed it as more legitimate. Thus, Jordanian children were similar to the Israeli-Jewish and Israeli-Palestinian children regarding evaluations of this form of cultural exclusion. These children viewed it as wrong based on the need to be inclusive and to make friends. The majority of Palestinian children, however, viewed it as legitimate based on stereotypes about someone from a different country. Conversely, only about one quarter of the Palestinian children judged this type of decision as wrong, giving prosocial and fairness reasons for why children should not exclude someone solely because they are from somewhere else. Given the political situation of nationality for Palestinian children, this finding was not surprising.

Future studies should examine age-related changes in Israeli and Arab children’s evaluations of exclusion. Research with Korean U.S. adolescents regarding friendship rejection, exclusion, and harassment based on nationality (Korean or U.S.) has shown that, overall, nationality was viewed as the least legitimate reason to exclude in friendship or victimization contexts, but it was viewed as more all right in a group exclusion context (Killen, Park, Lee-Kim, & Shin, 2005; Park & Killen, 2006). Thus, with 10 and 13 year old children, there was variability when participants legitimated excluding someone for reasons based on nationality. Overall, the present findings demonstrated that there is heterogeneity within Arab cultures regarding young children’s orientations towards inclusion and exclusion, and the cultural dimensions become salient for young children when making social and moral judgments. It will be beneficial in future research to continue to examine the developmental trajectory of their reasoning.

The results for exclusion based on cultural customs revealed that the majority of all children viewed this form of exclusion as wrong. There was cultural variability, however, with Israeli-Jewish, Israeli-Palestinian, and Jordanian children viewing it as more wrong than did the Palestinian children. All children explained their decision using inclusive justifications, about letting someone in the group who dresses differently. At the same time, Palestinian children were more likely to reason about this issue in terms of group functioning, that is, that the group will not work well if someone dresses differently. These findings indicate that the conventional norms about dress may be more salient for Palestinian children than for children in the other groups. Conventions about dress reflect religious and cultural customs that are embedded in cultures and acquire deeply important symbolic dimensions (Turiel, 2002). Further research should be designed to examine how Palestinian children understand cultural customs about dress and conformity and what makes it important and salient for them.

Reflections and Implications

The children in this project came from a range of backgrounds that varied in terms of religion, socioeconomic status, education, mobility, and exposure to violence. While none of the children lived in communities with daily exposure to violence, all of the children live in a region marked by intergroup tension, danger, and an infusion of negative stereotypes about the other in the media and in the curriculum (Bar-Tal & Teichman, 2005). The Palestinian children lived in conditions that were more stressful than the other three groups in terms of low socioeconomic conditions, reports of violence, and lack of mobility. Despite these conditions, the Palestinian children demonstrated a moral awareness about the importance of inclusion in peer group contexts. This was quite remarkable. These findings confirmed social-cognitive domain theory about the universality of young children’s social judgments, and provides further evidence that peer exchanges may provide a special context for promoting positive social development (Piaget, 1932).

Moreover, these findings challenge existing theories about the pervasiveness of stereotyping. While all children reported negative stereotypes regarding images of children from other cultures (Jewish or Arab), these stereotypes did not automatically carry over into decisions about who to include and who to exclude in peer situations. Thus, while stereotypes are a negative indication of children’s intergroup attitudes, more research is warranted to understand when these stereotypes are applied to decision making about social interactions.

These findings provide a number of avenues to pursue for further research, and hold promise for developing intervention programs designed to facilitate positive intergroup attitudes. We need to understand age-related and developmental changes regarding children’s moral judgments and stereotyped knowledge. In this study, we analyzed young children’s social judgments. What happens as children get older and become more influenced by media, parental and societal messages? How does social experience with a wider range of interactions with members of the same and other cultural groups influence intergroup attitudes? Further, how does the role of intergroup contact and the development of a Common Ingroup Identity (Gaertner & Dovidio, 2000; Gaertner & Dovidio, 2005) influence children’s application of stereotypes to inclusion and exclusion contexts? How might these factors affect youth members of cultural groups in conflict who do not live amidst the violence? These avenues of research will be particularly fruitful.

This study was part of a larger project which has demonstrated how educational television can have a positive impact on children’s attitudes and stereotypes. Sesame Street has been a model and a leader for designing media-based intervention projects around the world (Brenick, et al., in press). A successful aspect of the Sesame Street programs is the child focused format, in which peer exchanges and peer interactions are an essential dimension of the story format. We propose that peer interaction formats which combine intergroup themes would be particularly effective. Intergroup themes include interacting with others from different cultural and ethnic background, promoting notions of common identity (Gaertner & Dovidio, 2000), common group, shared experiences, and personalized interactions (Dixon, Durrheim, & Tredoux, 2005; Pettigrew & Tropp, 2005).

The findings in this study have additional implications for efforts to promote positive intergroup encounters with Israeli-Jewish and Arab children. Research on discourse and discussions among Palestinian and Israeli-Jewish adolescents indicate that these programs, while involving many complicated issues revolving around power relations and discourse, produce significant results (Bargal, 1990; Maoz, 2000). Young children begin with prosocial attitudes about peer relationships, and thus, intervention with young children may be the most effective way to produce positive change. The time for intervention is in childhood and adolescence, before stereotypes are deeply entrenched as has been shown in the social psychological literature with adults, in which stereotypes are difficult to change. Providing significant opportunities for intergroup friendships, counter-stereotypic messages and themes, as well as opportunities for learning about people from different cultures are important first steps towards reducing prejudice and stereotypes about the outgroup. The findings in this study provide hope in that young children living as members of cultures bombarded by negative stereotypes nonetheless value the importance of making inclusive decisions in peer situations. Future research with children and adolescence will unravel the complexities that underlie stereotypes and moral judgments, particularly with members of diverse cultures.

Acknowledgements

The Sesame Stories project from which the baseline data were used for this study was conducted in collaboration with the international team at Sesame Workshop, which included Charlotte Cole, Danny Labin, and Shari Rosenfeld. The research team at the University of Maryland included the co-authors along with Christina Edmonds, Solmaz Zabiheian, Rasha Dalbah and Colleen Klee.

This work was supported, in part, by a grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (#1(1T32HD007542) for traineeship support for the first author.

The first author acknowledges funding from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (1R01HD04121).

Appendix A

Coding Categories for Justifications

| Coding Categories | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Moral | ||

| Fairness | Appeals to moral principles, including fairness, and equality |

“It’s not fair”, “She should take turns”, |

| Inclusion | Appeals to inclusion of others based on equal access and the need for reducing negative stereotypes |

“Let him [Jewish boy] play so that they will know him” |

| Prosocial | Appeals to politeness and prosocial motives |

“It’s not nice” |

| Social-Conventional | ||

| Cultural stereotypes | Appeals to Jewish or Arab cultural membership as a basis for evaluating another child’s actions |

“Because he is Arab” , “Because he’s from a different place”, |

| Group Functioning | Appeals to the need to make the group function well |

“Because she has a striped hat and you have to have a dotted hat to join the party” |

| Personal | ||

| Personal Choice | Appeals to individual prerogatives including ownership |

“It’s okay if she doesn’t want to” |

| Selfish Motives | Appeals to a child’s selfish motives or personal negative preferences for why a child would do something |

, “She wants the kite”, |

Footnotes

Our access to the data reported in this article occurred as we (Fox, Killen, & Leavitt) were requested to conduct an evaluation of young children’s exposure to a new Sesame Street Workshop show, Sesame Stories, which aired in the Middle East in 2003, and was designed to reduce prejudice, and increase tolerance of the other. We were asked to design a pre-test/post-test evaluation study of how children’s viewing of Sesame Stories influenced their understanding of friendship, exclusion, and moral judgments. We conducted a similar evaluation for a Sesame show produced in 1998 and broadcasted in the Middle-East. The results were published as an empirical article (Cole et al., 2003). The study did not include a Jordanian sample, as did the present investigation, nor were there measures of children’s evaluations of peer exclusion (the assessments involved attributions of negative intention and evaluations of moral transgressions). The second evaluation project, for the show aired in 2003, was much larger, with a more diverse sample.

In this article, we report the findings for the pre-test data only. We do not report the results of the evaluation of the effects of the Sesame show on children’ social judgments (such a report was submitted to C. Cole, at Sesame Street Workshop, for those interested in these findings, also see Brenick et al, in press). Rather, this project had a basic research rationale, which was to publish the findings of how young Israeli-Jewish, Israeli-Palestinian, Jordanian, and Palestinian children evaluate moral transgressions and peer exclusion

References

- Aboud FE, Levy SR. Interventions to reduce prejudice and discrimination in children and adolescents. In: Oskamp S, editor. Reducing prejudice and discrimination. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2000. pp. 269–293. [Google Scholar]

- Alsoudi A, Mahdi A. Housework among married couples: Master status and gender. A comparative study between Jordan and Switzerland. Dirsat: Human and Social Sciences. 2004;31:503–520. [Google Scholar]

- Astor RA. Children's moral reasoning about family and peer violence: The role of provocation and retribution. Child Development. 1994;65(4):1054–1067. [Google Scholar]

- Bargal D. Contact is not enough - The contribution of Lewinian theory to inter-group workshops involving Palestinian and Jewish youth in Israel. International Journal of Group Tensions. 1990;20:179–92. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Tal D. Development of social categories and stereotypes in early childhood: The case of "the Arab" concept formation, stereotype and attitudes by Jewish children in Israel. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 1996;20:341–370. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Tal D, Teichman Y. Stereotypes and prejudice in conflict: Representations of Arabs in Israeli Jewish society. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Brenick A, Lee-Kim J, Killen M, Fox N, Raviv A, Leavitt L. Social judgments in Israeli and Arab children: Findings from media-based intervention projects. In: Lemish D, Götz M, editors. Children and Media at Times of Conflict and War. Hampton Press; Cresskill, NJ: in press. [Google Scholar]

- Cole C, Arafat C, Tidhar C, Zidan WT, Fox NA, Killen M, et al. The educational impact of Rechov Sumsum/Shara’a Simsim, a television series for Israeli and Palestinian children. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2003;27:409–422. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon J, Durrheim K, Tredoux C. Beyond the optimal contact strategy. American Psychologist. 2005;60:697–711. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.7.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle AB, Beaudet J, Aboud FE. Developmental patterns in the flexibility of children's ethnic attitudes. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 1988;19:3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Elbedour S, Bastien D, Center B. Identity formation in the shadow of conflict: Projective drawings by Palestinian and Israeli Arab children in the West Bank and Gaza. Journal of Peace Research. 1997;34:217–231. [Google Scholar]

- Gaertner SL, Dovidio JF. Reducing intergroup bias: The Common Ingroup Identity Model. The Psychology Press; Philadelphia, PA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gaertner SL, Dovidio JF. Categorization, recategorization and intergroup bias. In: Dovidio JF, Glick P, Rudman L, editors. Reflecting on the nature of prejudice: Fifty years after Allport. Blackwell; Malden, MA: 2005. pp. 71–88. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins NS. The new Arab family. The American University in Cairo Press; Cairo: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Horn S. Adolescents’ reasoning about exclusion from social groups. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:71–84. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.39.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn S, Killen M, Stangor C. The influence of group stereotypes on adolescents’ moral reasoning. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1999;19:98–113. [Google Scholar]

- Judd CM, Park B. Definition and assessment of accuracy in social stereotypes. Psychological Review. 1993;100:109–128. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.100.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khamis V. Post-traumatic stress disorder among school age Palestinian children. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2005;29:81–95. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killen M, Crystal D, Watanabe H. Japanese and American children’s evaluations of peer exclusion, tolerance of difference, and prescriptions for conformity. Child Development. 2002;73:1788–1802. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.t01-1-00506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killen M, Lee-Kim J, McGlothlin H, Stangor C. How children and adolescents evaluate gender and racial exclusion. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2002;67 (4, Serial No. 271) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killen M, Margie NG, Sinno S. Morality in the context of intergroup relationships. In: Killen M, Smetana JG, editors. Handbook of moral development. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2006. pp. 155–183. [Google Scholar]

- Killen M, McGlothlin H, Lee-Kim J. Between individuals and culture: Individuals' evaluations of exclusion from social groups. In: Keller H, Poortinga Y, Schoelmerich A, editors. Between biology and culture: Perspectives on ontogenetic development. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, England: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Killen M, Park Y, Lee-Kim J, Shin Y. Evaluations of children's gender stereotypic activities by Korean parents and nonparental adults residing in the United States. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2005;5:57–89. [Google Scholar]

- Killen M, Pisacane K, Lee-Kim J, Ardila-Rey A. Fairness or stereotypes?: Young children's priorities when evaluating group exclusion and inclusion. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:587–596. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.37.5.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killen M, Smetana JG. Social interactions in preschool classrooms and the development of young children’s conceptions of the personal. Child Development. 1999;70:486–501. [Google Scholar]

- Killen M, Stangor C. Children's social reasoning about inclusion and exclusion in gender and race peer group contexts. Child Development. 2001;72:174–186. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee-Kim J, Park Y, Killen M, Park Y. Korean American and Korean children’s reasoning about parental gender expectations regarding gender related peer activities. University of Maryland; College Park: 2006. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Liben LS, Bigler RS. The developmental course of gender differentiation: Conceptualizing, measuring and evaluating constructs and pathways. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2002;67(2) (Serial No. 269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maoz I. Power Relations in Intergroup Encounters: A Case Study of Jewish-Arab Encounters in Israel. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2000;24:259–277. [Google Scholar]

- Nucci L, Killen M., & Smetana, J. Autonomy and the personal: Negotiation and social reciprocity in adult-child social exchanges. In: Killen M, editor. Children's Autonomy and Social Competence. New Directions for Child Development. Jossey-Bass, Inc.; San Francisco, CA: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Nucci LP, Turiel E. God's word, religious rules and their relation to Christian and Jewish children's concepts of morality. Child Development. 1993;64:1485–1491. [Google Scholar]

- Park Y, Killen M. Individual deficits and group membership: U.S. and Korean adolescents’ evaluations of exclusion, peer rejection and victimization. University of Maryland; College Park: 2006. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew TF, Tropp LR. Allport's Intergroup Contact Hypothesis: Its history and influence. In: Dovidio JF, Glick P, Rudman L, editors. Reflecting on the nature of prejudice: Fifty years after Allport. Blackwell; Malden, MA: 2005. pp. 262–277. [Google Scholar]

- Piaget J. The moral judgment of the child. Harcourt, Brace; Oxford: 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Ruble DN, Martin CL. Gender development. In: Damon W, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of child psychology. 5th Vol. 3. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: 1998. pp. 933–1016. [Google Scholar]

- Slone M. The Nazareth riots: Arab and Jewish Israeli adolescents pay a different psychological price for participation. Journal of Conflict Resolution. 2003;47:817–836. [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG. Preschool children's conceptions of sex-typed transgressions. Child Development. 1986;57:862–871. [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG. Morality in context: Abstractions, ambiguities, and applications. In: Vasta R, editor. Annals of child development. Vol. 10. Jessica Kinglsey; London: 1995. pp. 83–130. [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG. Adolescent-parent conflict: Resistance and subversion as developmental process. In: Nucci L, editor. Conflict, contradiction, and contrarian elements in moral development and education. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2005. pp. 69–91. [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG. Social-cognitive domain theory: Consistencies and variations in children's moral and social judgments. In: Killen M, Smetana JG, editors. Handbook of moral development. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2006. pp. 119–153. [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG, Asquith P. Adolescents' and parents' conceptions of parental authority and personal autonomy. Child Development. 1994;65:1147–1162. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teichman Y, Zafrir H. Images held by Jewish and Arab children in Israel of people representing their own and the other group. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2003;34:658–676. [Google Scholar]

- Theimer CE, Killen M, Stangor C. Preschool children's evaluations of exclusion in gender-stereotypic contexts. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tibi B. Islam, and the cultural accommodation of social change. Westview Press; San Francisco: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Tisak MS. Domains of social reasoning and beyond. In: Vasta R, editor. Annals of child development. Vol. 11. Jessica Kingsley; London: 1995. pp. 95–130. [Google Scholar]

- Turiel E. The development of social knowledge: Morality and convention. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, England: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Turiel E. The development of morality. In: Damon W, editor. Handbook of child psychology. Social, emotional, and personality development. 5th Vol. 3. New York; Wiley: 1998. pp. 863–932. [Google Scholar]

- Turiel E. The culture of morality. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, England: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Turiel E. Resistance and subversion in everyday life. In: Nucci L, editor. Conflict, contradiction, and contrarian elements in moral development and education. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2005. pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Wainryb C. Moral development in culture: Diversity, tolerance, and justice. In: Killen M, Smetana JG, editors. Handbook of moral development. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2006. pp. 211–240. [Google Scholar]