Abstract

In contrast to a majority of cancer types, the initiation of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is intimately associated with a chronically diseased liver tissue, with one of the most prevalent etiological factors being hepatitis B virus (HBV). Transformation of the liver in HBV-associated HCC often follows from or accompanies long-term symptoms of chronic hepatitis, inflammation and cirrhosis, and viral load is a strong predictor for both incidence and progression of HCC. Besides aiding in transformation, HBV plays a crucial role in modulating the accumulation and activation of both cellular components of the microenvironment, such as immune cells and fibroblasts, and non-cellular components of the microenvironment, such as cytokines and growth factors, markedly influencing disease progression and prognosis. This review will explore some of these components and mechanisms to demonstrate both underlying themes and the inherent complexity of these interacting systems in the initiation, progression, and metastasis of HBV-positive HCC.

Keywords: hepatitis B, hepatocellular carcinoma, tumor microenvironment, leukocytes, cytokines, growth factors

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the few cancers in which a continued increase in incidence has been observed over recent years. Globally, there are approximately 750 000 new cases of liver cancer reported each year [1]. Importantly, population-based studies show that HCC ranks as the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide [1]. Although surveillance and surgical interventions have improved prognosis, a large proportion of HCC patients display symptoms of intrahepatic metastases or postsurgical recurrence [2], with a five-year survival rate of around only 30–40%.

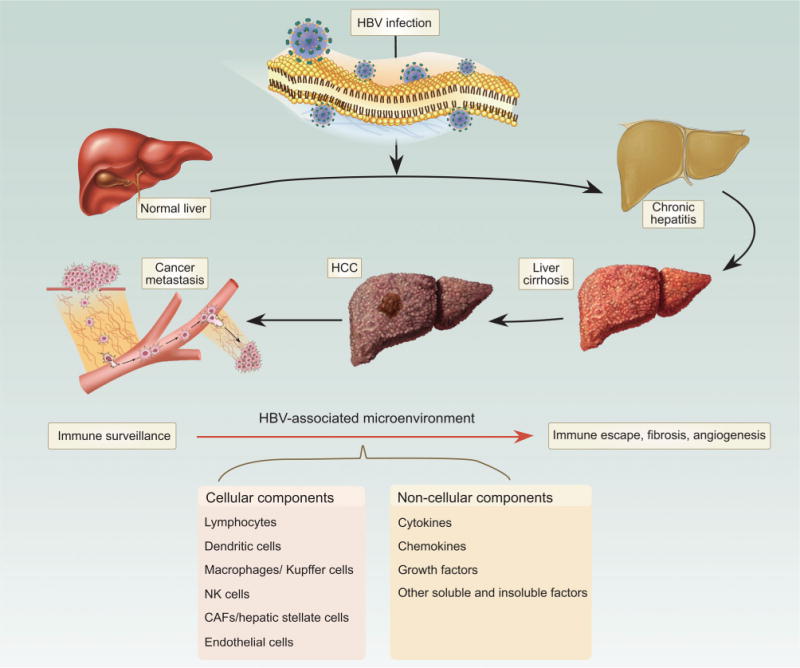

In contrast to a majority of cancer types, such as breast, lung, and prostate cancer, in which a tumor emerges within a relatively healthy tissue, the initiation of HCC is intimately associated with a chronically diseased liver tissue, induced by etiological factors such as hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, carcinogen/toxin exposure, and/or other environmental or genetic factors including excessive alcohol consumption or obesity and metabolic syndrome. Among these suspected etiological factors, HBV infection accounts for about 60% of total liver cancer cases in developing countries and around 23% of cases in developed countries [3]. The HBV-initiated tumorigenic process often follows from or accompanies long-term symptoms of chronic hepatitis, inflammation and cirrhosis. Consistent with an important role for HBV in HCC, the persistent presence of HBV DNA in the serum of infected individuals has been found to be a strong indicator for the development of HCC [4]. Moreover, HCC patients with higher levels of serum HBV DNA have poor prognoses, including risks of death, metastasis, and recurrence following surgery [5]. Over the past several years, multiple mechanistic studies on one protein encoded by the HBV genome, HBx, have indicated that HBx plays a critical role in HBV-associated liver pathogenesis, including tumorigenesis by functioning as an oncogene [6,7]. Together with inactivation of p53 and activation of the Wnt pathway, both commonly detected in HCC, HBx and possibly other HBV-encoded proteins can act as drivers for HCC initiation and progression. Simultaneously, bothcell-autonomous and non-cell-autonomous pathological changes occur in association with this HBV-initiated tumorigenic process (Fig. 1). These changes can be distinct from those genetic and epigenetic alterations inside hepatocytes required for tumor initiation, indicating a role for the HBV-associated tumor microenvironment in affecting different stages of HCC progression and prognosis.

Figure 1.

Cellular and subcellular components of the microenvironment are affected by HBV throughout the entire pathogenic process.

Acting in combination with HBV to drive HCC initiation and progression, and ultimately to affect prognosis of the patient, is the genome itself of the patient. Numerous groups have performed genomewide association studies, and identified variants of genes and their regulatory sequences which affect both the predisposition and the prognosis of patients from initial infection with HBV through metastasis and mortality from HBV-associated HCC. Importantly, several studies have shown that genes regulating immune functionality, such as HLA variants, IL-28B, STAT4, and MICA, play roles in predisposing patients to acute and chronic HBV infection, cirrhosis, and/or HCC, highlighting the importance of immune functionality in the development of this disease from the beginning stage through every step of the pathological process [8–16]. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in a multitude of other genes involved in immune function, such as CTLA-4, IFN-α, and IL-6 among numerous others [17–19], confirm this notion and require further work to generate a better understanding of the tumor microenvironment.

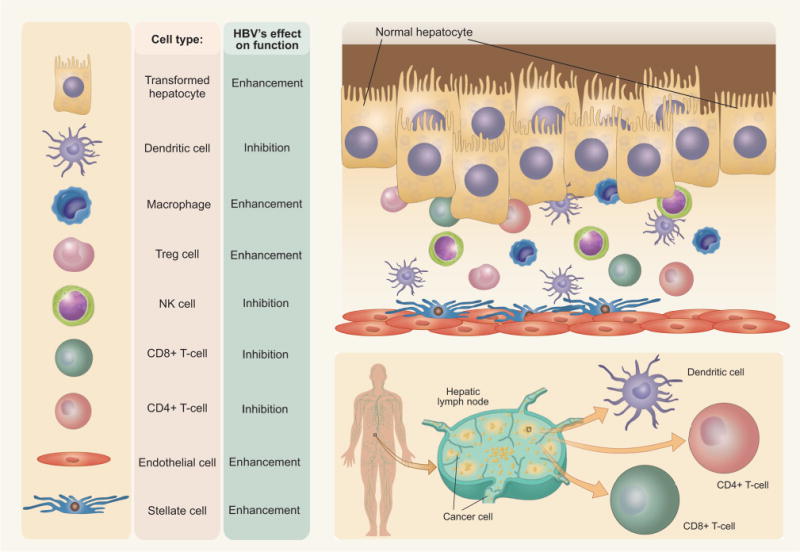

The tumor microenvironment is a complex system of both cellular and subcellular components with reciprocal signaling that contributes critically to the carcinogenic process (Fig. 2). Tumorigenesis does not occur independently of the microenvironment, and the stroma is uniformly activated inappropriately in cancer to contribute to malignant characteristics of the tumor. Because HCC develops largely upon a chronically inflamed and fibrotic tissue background, the complexity of the liver tumor microenvironment is much higher than that of many other types of cancer, consisting of tumor cells, stromal cells, and their secreted proteins within the extracellular matrix (ECM). HBV infection-triggered inflammatory and/or fibrotic processes, with the extensive concomitant production and activation of cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors, as well as the infiltration of leukocytes and activation of tissue-resident immune and fibroblast populations, are believed to create a dynamic microenvironment that contributes to different stages of HCC development. This review will explore some of these components and mechanisms to demonstrate both underlying themes and the inherent complexity of these interacting systems in the initiation, progression, and metastasis of HBV-positive HCC.

Figure 2.

HBV modulates the activity of cellular components of the tumor microenvironment, having the potential to both enhance and inhibit activity.

CELLULAR COMPONENTS OF THE HBV-ASSOCIATED HCC ENVIRONMENT

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes

Currently, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes are considered the primary immune component involved in the host antitumor reaction to solid tumors [20]. T cells which have infiltrated the tumor can target transformed cells and mediate the adaptive immune response [21,22]. During this process, the differentiation of naïve CD4+ T cells into interferon gamma (IFN-γ)-producing T helper type 1 (Th1) cells promotes CD8+ T-cell-mediated cancer immunosurveillance [23,24]. Both cell-intrinsic and cell-extrinsic mechanisms have been observed to contribute to suppression of CD8+ T-cell function in the HCC microenvironment via two prominent mechanisms, including T-cell exhaustion via PD-1-mediated inactivation of CD8+ T cells [25], and regulatory T (Treg)-mediated suppression. In most cases, CD4+CD25+Treg cells are more prevalent than CD8+ T cells in HCC tumor tissue compared with adjacent benign tissue; this predominance of Treg cells is associated with a worse prognosis. Functionally, Treg cells impair cytotoxic CD8+ T-cell proliferation, activation, degranulation, and production of granzyme A, granzyme B, and perforin [26]. In addition, increasing Treg cell prevalence has been shown to correlate strongly with advancing stages of HCC progression [27].

During HBV infection, while CD8+ T cells seem to control HBV replication through an IFN-γ-dependent mechanism [28], Treg cells are significantly induced via HBx-stimulated production of transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) [29]. Treg cells help to maintain a tolerogenic environment in the liver that protects the organ from immune damage, being capable of suppressing the proliferation and IFN-γ production of autologous peripheral blood mononuclear cells mediated by HBV antigen [30]. However, they also compromise viral control during acute HBV infection [31], and chronic HBV-associated Treg accumulation is considered to significantly contribute to poor prognosis [26]. Importantly, HBV-triggered TGF-β production also promotes Treg cell recruitment through a microRNA-34a-mediated tumor-cell-derived chemokine CCL22 signal, thereby demonstrating HBV as a potent etiological factor to predispose HCC patients for the development of intravenous metastasis [32]. In addition to CD4+FoxP3+Treg cells, an IL-10-producing type 1 regulatory T (Tr1) cell population negative for FoxP3 is also found in HBV-carrier mice (mice which have had an adenoviral vector expressing HBV’s genome administered via hydrodynamic injections and developed tolerance towards HBV as demonstrated by a lack of generation of anti-HBs antibodies after peripheral administration of HBsAg), which was confirmed to contribute to immune tolerance in the liver microenvironment [33]. Therefore, a combination of depletion of Treg cells and concomitant stimulation of effector T cells may represent an effective strategy to reduce HCC metastasis and recurrence, and to improve prognosis for HCC patients, particularly those infected with HBV.

Dendritic cells

Dendritic cells (DCs) are a heterogeneous group of antigen-presenting cells (APCs) originating from the bone marrow that play a critical role in the initiation of primary T-cell responses [34,35]. The central role of DCs in the presentation of tumor antigens is critical for initiating and regulating T-cell immunity [35,36], which may provide opportunities for therapeutic enhancement of immunogenicity. The potential of adoptive transfer of DCs as a cancer vaccination has been proposed as an antitumor immunotherapy for HCC, but requires a more complete understanding of the immune microenvironment to predict possible ramifications of its usage.

The two populations of DCs, myeloid DCs (MDCs)and plasmacytoid DCs(PDCs), can be distinguished both by their ontogeny and their functional capacities [37]. MDCs are of myeloid origin whereas PDCs could be of lymphoid origin [38]. HBV-associated HCC patients were reported to have an aberrant composition of the DC population in their hepatic lymph nodes (LNs). Hepatic LNs of HCC patients with HBV or HCV infection showed a 1.5-fold reduction in mature MDCs and a 4-fold increase in PDCs in their T-cell-specific subcompartments compared with those of patients with viral hepatitis only [39]. The aberrant composition of the DC population in hepatic LNs of HCC patients may be caused by abnormal precursor frequencies in blood and/or by alterations of DC trafficking, but the mechanism is still largely unknown. PDCs can rapidly produce large amounts of type I interferon upon toll-like receptor (TLR) stimulation or viral exposure; however, their ability to cross-present antigens may be limited, as PDC activity often leads to production of IL-10-secreting T cells, Tregs, or tolerance [40]. The functionality of these cells may be altered in tumors, especially with regard to their interferon-producing capabilities: data have shown altered or diminished functions in ovarian cancer [41], head and neck squamous carcinoma [42], non-small-cell lung cancer [43], and melanoma [44], among others. In chronic HBV-associated hepatitis patients, PDCs display an impaired ability to secrete IFN-α following ex vivo stimulation with TLR9 ligands [45], which in turn may contribute to the persistence of chronic infection, and also to the survival of transformed cells. The abundance of tumor-infiltrating DCs has also been shown to correlate with functional consequences in patients: groups have found that their increased number correlates with longer tumor-free survival, recurrence-free survival, and overall survival after surgical resection, demonstrating once again the importance of functional DCs [46,47].

Macrophages and Kupffer cells

Macrophages are phagocytes of the monocytic lineage that have antigen-presenting and cytokine-producing capacities. Kupffer cells are the resident macrophages of the liver, and are the most abundant innate immune cells in the liver [48]. They play important roles throughout the entire pathogenic process, from initial HBV infection to HCC initiation and progression. In early stages after infection, Kupffer cells act in both inflammatory responses and in generation of tolerance [33,49–53]. While no causal role for Kupffer cells has been demonstrated during fibrosis development, their accumulation and its correlation with worsening fibrosis severity have been observed [54,55], perhaps by production of reactive oxygen species, in-flammatory cytokines, and growth factors such as IL-6, TNFα, IL-1α, IL-1β, PDGF, and TGF-β, which activate hepatic stellate cells (HSCs), or enhance killing of infected and bystander hepatocytes via TRIL, FasL, perforin, and granzymes [54,56–58]. During HBV-initiated carcinogenesis, both HBV and dying hepatocytes trigger production of cytokines and growth factors from Kupffer cells including IL-6 and TNFα to drive more inflammation and compensatory proliferation [51,59], as well as production of reactive oxygen species, which generate more mutations in transforming hepatocytes [60]. However, not only inflammatory effects from these cells, but also tolerogenic and M2 activation-induced effects play very important roles in tumorigenesis. Interestingly, a humanized mouse model of HBV infection in A2/NSG-hu HSC/Hep mice demonstrated that HBV-mediated liver disease was associated with high levels of infiltrating human macrophages with an M2-like activation phenotype [61], which suggests a critical role for macrophage polarization in HBV-induced immune impairment and liver pathology. This study and others have established a link between HBV and the M2-like activation of macrophages, generally through HBsAg binding to the surface of the monocyte/macrophage and binding to CD14 [62]. This results in reduced production of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-12, IL-18, IL-1β, and IL-6 and increased production of IL-10 and TGF-β, probably via inhibition of JNK, ERK, and NF-κB signaling [52,61–68]. These macrophages in turn accumulate in diseased and tumor tissue [69], and provide positive feedback signals, resulting in more M2-polarized macrophages. Finally, Kupffer cells or macrophages can also impact disease progression by negatively affecting T-cell-mediated antitumor activity both through expression of PD-L1 on monocytes blocking T-cell activation and by inducing senescence of Tim3+ CD4+ and Tim3+ CD8+ cells [70,71]. These possible mechanistic links have been corroborated with clinical data showing that an abundance of peritumoral macrophages correlates strongly with worse overall survival and tumor recurrence of HCC patients [72].

Natural killer cells

Natural killer (NK) cells comprise the majority of lymphocytes in the healthy human liver [73]. The frequency of NK cells is even higher in the liver of patients with chronic HBV and HCV infection [74,75]. The recruitment of NK cells largely depends on chemokines from Kupffer cells, and the function and survival of NK cells are regulated by cytokines from Kupffer cells, liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSECs), and T cells [76]. In HBV-infected patients, although NK cells in peripheral blood express higher levels of the activating receptors NKp30, NKp46, and NKG2C [77], NK cell activation does not induce all effector functions to an equally high degree. During HBV infection, MICA, a ligand of the NKG2D receptor, is induced at the early stage of infection, and soluble MICA levels were associated with MICA variants that modulate the NK- and T-cell-mediated immune responses [78], which play a crucial role in HCC development in HBV-associated HCC patients. In addition, a selective defect in NK cell function during persistent HBV infection was demonstrated via several different mechanisms including induction by IL-10 and TGF-β, as well as HBV-induced up-regulation of Tim-3 expression in NK cells, which in turn suppresses NK cell functions [79,80].

Carcinoma-associated fibroblasts and HSCs

Carcinoma-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) are large spindle-shaped cells, with indented nuclei and stress fiber formation for well-developed cell–matrix interactions, which are the major source of collagen in the HCC stroma. There is a complicated crosstalk between CAFs and HCC tumor cells, in which they collaboratively lead to HSC activation and consequent ECM deposition [81]. CAFs enhance ECM quantity and stiffness, which provides a reservoir for growth factors secreted by both tumor and stromal cells, thereby allowing this fibrotic context to promote angiogenesis and modulate activity of immune cells. During the hepatic fibrotic process, activation of HSCs, also known as Ito cells, is considered to be the central event that contributes to hepatic malignancies. In HBV-associated HCC patients, levels of peritumoral α-SMA, a specific biomarker for HSCs, were shown to be directly correlated with poor prognosis [82]. Compared with quiescent HSCs, peritumoral HSCs and intratumoral CAFs express considerable numbers of dysregulated genes associated with fibrogenesis, inflammation, and progression of HCC [82].

Endothelial cells

Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSECs) comprise much of the intralobular vasculature of the liver, lining the sinusoids, the site of exchange of small molecules to and from the bloodstream. These cells are unique among endothelium in their lack of a basement membrane with non-diaphragmed fenestrae, as well as in their high endocytic activity to clear waste products from circulation [83]. LSECs have been shown to play important functional roles throughout the course of hepatic injury and HCC tumorigenesis. During hepatic injury, crosstalk between HSCs and endothelial cells regulates fibrogenesis, with factors such as HGF from healthy endothelial cells, both resident and recruited progenitors, suppressing activation of HSCs [83,84]. LSECs have been implicated in the production of other cytokines and growth factors as well, such as Ang2, TGF-β1, IL-8, CCL2, and CXCL16, among others [85–87]. LSECs may also intriguingly have antigen-presenting capabilities. A series of studies demonstrated that these cells have the majority, if not all, of the machinery necessary to digest and present antigens, and may be important for inducing tolerance [88].

Arguably the most important function of LSECs in the context of chronic liver disease, tumor development, and progression is angiogenesis. LSECs, derived from both the resident LSEC population and from circulating precursors, respond to signals within the microenvironment such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and fibroblast growth factor to change their proliferative state and to express different adhesion molecules, resulting in sprouting new vasculature [89–91]. This in turn results in enhanced blood supply to injured liver tissue and tumor tissue. Thus, angiogenesis is a key survival factor for HCC tissue, especially in HBV-associated HCC patients, and microvessel density, a marker for the amount of vasculature present, correlates strongly with poor prognosis in HCC patients [92,93].

In the context of HBV-associated HCC, endothelial cells not only play a role in enhancing progression via the aforementioned mechanisms, but also are a critical interacting factor in the development of a particularly malicious form of intrahepatic metastasis, the portal vein tumor thrombus (PVT). Vascular invasion by HCC is a poor prognostic indicator, and involvement of the portal vein is particularly dangerous: consequences include extensive intrahepatic metastases, deterioration of liver function, and portal hypertension, with greater portal vein occlusion yielding ever worse results [94]. Patients with PVT have been shown to have a very poor survival rate, and also to have HBV as a probable predisposing factor [32]. Models of PVT and studies on this disease are currently very limited; however, it is likely that the interaction between the tumor cells and the endothelium plays an important role in the promotion and preservation of this disease.

NON-CELLULAR FACTORS IN THE HBV-ASSOCIATED HCC MICROENVIRONMENT

Cytokines and chemokines

It has been well established that cytokines and chemokines are important mediators of cancer-promoting inflammation in HCC. These secreted proteins have been shown to target primarily immune cells, modulating their motility, proliferation, and functionality. However, they also have important effects on fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and epithelial cells to modulate the development and progression of cancer, including processes such as evasion of the immune system, angiogenesis, invasion, and dissemination [95–97]. Data from both patient serum and tissue samples, as well as the same sources from animal models of chronic liver disease and hepatocarcinogenesis, have demonstrated the prevalence of many soluble mediators of inflammation, with a substantial number correlating with disease stage and progression in different patterns. Polymorphisms in promoters and coding sequences of these cytokines have also been examined, and SNPs have demonstrated association with both disease occurrence and outcomes.

In the context of HBV-associated HCC, much work has been done examining serum and tissue levels of cytokines and also possible polymorphisms as predisposing factors. Mechanistic understanding of the results for many of these cytokines is lacking; however, key themes can be gleaned from the data generated, which will be illustrated with the help of examples in the rest of this section. First, inflammation and chronic liver disease are essential components of the HBV-associated HCC tumorigenic process and its established microenvironment. Second, this is a dynamic process, and cytokines that play an important pro- or antitumorigenic role before the appearance of clinically detectable tumors may have a diminished or even reversed role after the emergence of these tumors. Third, circulating levels of cytokines in serum do not necessarily demonstrate the status of those molecules in the local tumor microenvironment. Finally, while there are several key factors in the tumorigenic process common to several etiologies of HCC, there are also hepatotropic virus-specific and even HBV-specific players and predisposing factors.

Many cytokines and chemokines have been shown to play important functional roles in the development and progression of liver cancer. For example, IL-1α released by hepatocytes enhances their compensatory proliferation following hepatocyte death associated with liver tumorigenesis [98,99], while IL-1β produced by multiple sources in the HCC microenvironment including hepatocytes, monocytes, and stellate cells is important for tumorigenesis [100–103]. IL-6, a cytokine which can be induced by IL-1 signaling among other mechanisms, is secreted by various cell types such as hepatocytes, hepatocytic liver cancer progenitors, and Kupffer cells. IL-6 exhibits potent protumorigenic effects such as modulation of proliferation, and survival of hepatocytes and differentiation of Th17 cells, a T-cell subpopulation whose accumulation has been correlated with microvessel density and poor prognosis in HCC patients [99,104–109]. TNFα and other TNF superfamily ligands are critical in promoting liver cancer via the NF-κB pathway, particularly by enhancing inflammation [110,111]. The chemokine CCL2, which is chemotactic for monocytes and macrophages, and CCL3, which is chemotactic for activated T cells, are increasingly elevated throughout the course of liver disease progression and display high levels in tumor and non-tumor liver tissues, with concomitant accumulation of their attracted target cell populations [112]. These factors, as well as numerous others, have been shown to be particularly important in mediating the interactions between hepatocytes and stromal cells, including Kupffer cells, HSCs, and recruited immune populations in the microenvironment, as demonstrated by functional studies in mouse models and by evaluation of HBV-positive HCC patient serum and tissue samples (a selection of these factors is shown in Table 1; associated references are included in the online-only document ‘Supplemental References for Table 1’). It is worth noting that care must be taken when selecting mouse models for studies on liver tumorigenesis and progression, as some models may lead to results that do not fully reflect the pathological nature of the liver tissue, with its associated inflammation and fibrosis, during HCC development in human patients. For example, the MDR2 knockout mice, which develop spontaneous biliary fibrosis and resultant chronic inflammation, dysplasia, and HCC, showed a reliance on TNFα-NF-κB signaling in transformed hepatocytes for their survival and progression to HCC, while other studies utilizing the chemical carcinogen diethylnitrosamine (DEN) demonstrated that decreased NF-κB signaling in hepatocytes resulted in increased tumorigenesis [59,110]. Similarly, DEN-induced carcinogenesis was minimized in STAT3 knockout mice, but carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) treatment was in contrast shown to induce tumor formation in the same mouse model, thus demonstrating a reliance on liver damage, hepatocyte death, and compensatory proliferation in an inflammatory context to promote tumorigenesis [113].

Table 1.

Selected cytokines, immune regulatory proteins, and their receptors in HBV-associated HCC prognosis

| Soluble factor | Tissue type | Stage(s) evaluated | mRNA or protein | Conclusion | Supplemental reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCL2 | Serum | HCC | Protein | Higher in HCC patients than chronic HBV controls | 1 |

| CCL3 | Liver | HCC | mRNA | Higher expression in patients with HBV, HCV, and HCC than other liver diseases or healthy controls | 2 |

| CCL5 | Liver | HCC | mRNA | Higher expression in patients with HBV, HCV, and HCC than other liver diseases or healthy controls | 2 |

| CCL15 | Liver | HCC | Protein | Higher expression in tumor tissue than in non-tumor tissue | 3 |

| Serum | HCC | Protein | Higher in HCC patients than cirrhotic or healthy controls | 3 | |

| CCL22 | Liver | HCC | mRNA | Higher expression in HBV+ primary tumors than HBV− primary tumors; higher expression in metastases than primary tumors | 4 |

| CXCL1 | Liver | HCC | mRNA | Higher expression in patients with HBV and HCC than other liver diseases or healthy controls | 2 |

| Serum | HCC | Protein | Higher in HCC patients than healthy controls | 5 | |

| CXCL10 | Liver | HCC | mRNA | Higher expression in patients with HBV, HCV, and HCC than other liver diseases or healthy controls | 2 |

| CXCL12 | Liver | HCC | Protein | Higher expression in tumor tissue than in cirrhotic or non-tumor tissue | 6 |

| FasL | Liver | HCC | mRNA | More in cirrhotic than chronic hepatitis, peritumoral, HCC, or healthy tissue; more in peritumor than HCC; similar in HCC and healthy tissue | 7 |

| Serum | Cirrhosis, HCC | Protein | Higher in cirrhosis and HCC patients, slightly higher in cirrhotic than HCC | 8, 9 | |

| Fas | Liver | HCC | mRNA | More in cirrhotic than chronic hepatitis, peritumoral, HCC, or healthy tissue; more in peritumor than HCC; More in HCC than healthy tissue | 7 |

| IFN-γ | Serum | Cirrhosis, HCC | Protein | Higher in HCC but not cirrhosis patients | 10 |

| IL-1α | Liver | HCC | Protein | Higher expression in peritumor than in tumor or healthy tissue | 11 |

| IL-1β | Liver | HCC | mRNA | More in peritumor than cirrhotic or chronic hepatitis; more in peritumor than HCC; similar in HCC and healthy tissue | 7 |

| IL-2 | Liver | HCC | Protein | High expression in peritumor tissue predicts better prognosis | 12 |

| IL-6 | Liver | HCC | Protein | Higher expression in peritumor than in tumor or healthy tissue | 11 |

| Serum | Cirrhosis, HCC | Protein | Higher in cirrhosis and HCC patients than healthy controls; higher with advancing stages of liver disease and HCC | 13–17 | |

| IL-8 | Serum | Chronic Liver Disease, HCC |

Protein | Higher in chronic liver disease than in HCC patients, higher in HCC patients than healthy controls | 18 |

| IL-10 | Serum | HCC | Protein | Higher in HCC patients than chronic HBV, chronic HCV, or healthy controls | 17, 19 |

| Liver | HCC | mRNA, protein | Higher in HCC patients than healthy controls | 20 | |

| IL-11 | Liver | HCC | mRNA, protein | Higher in tumor predicts bone metastases, poor survival after resection | 21–23 |

| IL-12 | Serum | Cirrhosis, HCC | Protein | Higher in cirrhosis and HCC patients | 14, 24 |

| IL-15 | Liver | HCC | Protein | High expression in peritumor tissue predicts better prognosis | 12 |

| IL-17/R | Liver | HCC | Protein | Higher in tumor associated with poor survival, increased recurrence, and increased vascularization | 25, 26 |

| IL-18/R | Liver | HCC | mRNA, protein | Higher expression in tumor tissue than in healthy tissue; higher expression in surrounding diseased tissue than tumor tissue | 27, 28 |

| Serum | Cirrhosis, HCC | Protein | Higher in HCC patients than cirrhotic or healthy controls | 29, 30 | |

| LTα/β/R | Liver | HCC | mRNA | Higher expression in patients with HBV, HCV, and HCC than other liver diseases or healthy controls | 2 |

| Midkine | Liver | HCC | Protein | Higher expression in tumor tissue than in non-tumor tissue or healthy controls; correlates with HBV DNA | 31 |

| MDC | Serum | HCC | Protein | Higher in HCC patients than chronic HBV or healthy controls | 32 |

| MSPα | Serum | HCC | Protein | Higher in HCC patients than chronic HBV or healthy controls | 32 |

| PD-1/L1 | Serum | HCC | Protein | Circulating PD-1/L1 correlate with intratumor PD-L1 expression, severity of disease, and overall and tumor-free survival post-cryoablation | 33 |

| TNF-α | Liver | HCC | Protein | Expression in tumor and peritumor but not non-tumor tissue; correlates with degree of differentiation | 34 |

| Serum | Cirrhosis, HCC | Protein | Higher in cirrhosis and HCC patients | 10 | |

| TRILR1 | Liver | HCC | Protein | Lower in HBV+ and HCV+ tumor than non-tumor | 35 |

Wang, WW, Ang, SF, Kumar, R et al. Identification of serum monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and prolactin as potential tumor markers in hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS ONE 2013; 8:e68904.

Haybaeck, J, Zeller, N, Wolf, MJ et al. A lymphotoxin-driven pathway to hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Cell 2009; 16:295–308.

Li, Y, Wu, J, Zhang, W et al. Identification of serum CCL15 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Br. J. Cancer 2013; 108:99–106.

Yang, P, Li, QJ, Feng, Y et al. TGF-beta-miR-34a-CCL22 signaling-induced Treg cell recruitment promotes venous metastases of HBV-positive hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Cell 2012; 22:291–303.

Wu, FX, Wang, Q, Zhang, ZM et al. Identifying serological biomarkers of hepatocellular carcinoma using surface-enhanced laser desorption/ionizationtime-of-flight mass spectroscopy. Cancer Lett. 2009; 279:163–170.

Li, W, Gomez, E, and Zhang, Z. Immunohistochemical expression of stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1) and CXCR4 ligand receptor system in hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007; 26:527–533.

Bortolami, M, Kotsafti, A, Cardin, R, and Farinati, F. Fas/FasL system, IL-1beta expression and apoptosis in chronic HBV and HCV liver disease. J. Viral Hepat. 2008; 15:515–522.

Wang, XZ, Chen, XC, Chen, YX et al. Overexpression of HBxAg in hepatocellular carcinoma and its relationship with Fas/FasL system. World J. Gastroenterol. 2003; 9:2671–2675.

Chen, J, Su, XS, Jiang, YF et al. Transfection of apoptosis related gene Fas ligand in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells and its significance in apoptosis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2003; 11:2653–2655.

Saxena, R, Chawla, YK, Verma, I, and Kaur, J. IFN-γ (+874) and not TNF-α (−308) is associated with HBV-HCC risk in India. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2014; 385:297–307.

Jiang, R, Deng, L, Zhao, L et al. miR-22 promotes HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma development in males. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011; 17:5593–5603.

Zhou, H, Huang, H, Shi, J et al. Prognostic value of interleukin 2 and interleukin 15 in peritumoral hepatic tissues for patients with hepatitis B-related hepatocellular carcinoma after curative resection. Gut 2010; 59:1699–1708.

Tangkijvanich, P, Vimolket, T, Theamboonlers, A et al. Serum interleukin-6 and interferon-gamma levels in patients with hepatitis B-associated chronic liver disease. Asian Pac. J. Allergy Immunol. 2000; 18:109–114.

Song, LH, Binh, VQ, Duy, DN et al. Serum cytokine profiles associated with clinical presentation in Vietnamese infected with hepatitis B virus. J. Clin. Virol. 2003; 28:93–103.

Ataseven, H, Bahcecioglu, IH, Kuzu, N et al. The levels of ghrelin, leptin, TNF-alpha, and IL-6 in liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma due to HBV and HDV infection. Mediators Inflamm. 2006; 2006:78380.

Kao, JT, Lai, HC, Tsai, SM et al. Rather than interleukin-27, interleukin-6 expresses positive correlation with liver severity in naïve hepatitis B infection patients. Liver Int. 2012; 32:928–936.

Wang, XD, Wang, L, Ji, FJ et al. Decreased CD27 on B lymphocytes in patients with primary hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Int. Med. Res. 2012; 40:307–316.

El-Tayeh, SF, Hussein, TD, El-Houseini, ME et al. Serological biomarkers of hepatocellular carcinoma in Egyptian patients. Dis. Markers 2012; 32:255–263.

Hsia, CY, Huo, TI, Chiang, SY et al. Evaluation of interleukin-6, interleukin-10 and human hepatocyte growth factor as tumor markers for hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2007; 33:208–212.

Geng, L, Deng, J, Jiang, G et al. B7-H1 up-regulated expression in human hepatocellular carcinoma tissue: correlation with tumor interleukin-10 levels. Hepatogastroenterology 2011; 58:960–964.

Xiang, ZL, Zeng, ZC, Tang, ZY et al. Potential prognostic biomarkers for bone metastasis from hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncologist 2011; 16:1028–1039.

Xiang, ZL, Zeng, ZC, Fan, J et al. Expression of connective tissue growth factor and interleukin-11 in intratumoral tissue is associated with poor survival after curative resection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2012; 39:6001–6006.

Gao, YB, Xiang, ZL, Zhou, LY et al. Enhanced production of CTGF and IL-11 from highly metastatic hepatoma cells under hypoxic conditions: an implication of hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis to bone. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2013; 139:669–679.

Liu, L, Xu, Y, Liu, Z et al. IL12 polymorphisms, HBV infection and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in a high-risk Chinese population. Int. J. Cancer 2011; 128:1692–1696.

Gu, FM, Li, QL, Gao, Q et al. IL-17 induces AKT-dependent IL-6/JAK2/STAT3 activation and tumor progression in hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol. Cancer 2011; 10:150-162.

Liao, R, Sun, J, Wu, H et al. High expression of IL-17 and IL-17RE associate with poor prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013; 32:3-13.

Chia, CS, Ban, K, Ithnin, H et al. Expression of interleukin-18, interferon-gamma and interleukin-10 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Immunol. Lett. 2002; 84:163–172.

Zhang, Y, Li, Y, Ma, Y et al. Dual effects of interleukin-18: inhibiting hepatitis B virus replication in HepG2.2.15 cells and promoting hepatoma cells metastasis. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2011; 301:G565–G573.

Tangkijvanich, P, Thong-Ngam, D, Mahachai, V et al. Role of serum interleukin-18 as a prognostic factor in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. World J. Gastroenterol. 2007; 13:4345–4349.

Cheng, KS, Tang, HL, Chou, FT et al. Cytokine evaluation in liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology 2009; 56:1105–1110.

Dai, LC, Yao, X, Lu, YL et al. [Expression of midkine and its relationship with HBV infection in hepatocellular carcinomas]. (Chinese) Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 2003; 83:1691–1693.

Liu, T, Xue, R, Dong, L et al. Rapid determination of serological cytokine biomarkers for hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma using antibody microarrays. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. (Shanghai) 2011; 43:45–51.

Zeng, Z, Shi, F, Zhou, L et al. Upregulation of circulating PD-L1/PD-1 is associated with poor post-cryoablation prognosis in patients with HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS ONE 2011; 6:e23621.

Qiu, B, Jiang, W, Zhang, J et al. Measurement of transporter associated with antigen processing 1 and tumor necrosis factor alpha expression in hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma and peritumor cirrhosis tissues using tissue chip technology. Hepatogastroenterology 2013; 60:14–18.

Yano, Y, Hayashi, Y, Nakaji, M et al. Different apoptotic regulation of TRAI-Lcaspase pathway in HBV- and HCV-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2003; 11:499–504.

In clinical settings, evaluation of HCC patient samples has yielded interesting insights towards differing roles of cytokines at different stages of liver disease. For example, IL-1α, IL-1β, and IL-6, as mentioned above, play important protumorigenic roles. However, examination of patient tumor tissues has shown higher expression of these same factors in peritumor tissue than in the actual tumor itself, suggesting that while these cytokines are very important for tumor initiation, their inflammatory characteristics may not be beneficial for the developing tumor and are perhaps required to be suppressed within the tumor microenvironment [114,115]. Consistent with this notion, FasL, an important trigger for Fasinduced cell death, is commonly seen elevated in liver tissue and serum in both patients with cirrhosis and HCC. However, higher levels of FasL were seen in patients with cirrhosis alone compared to those with HCC, and more abundant in peritumor tissue compared to tumor tissue within the diseased liver [114,116,117]. Other cytokines and chemokines which may play important roles in the progression phase of HCC, however, may be only minimally expressed or not present at all during the initial stages of the disease. A well-studied example of this phenomenon is the cytokine IL-10, a critical Th2 cytokine which blocks the activities of more inflammatory Th1 T-cell cytokines. IL-10 is greatly increased in the serum and tissue of patients with HCC; however, it is not uniformly present in patients with chronic liver disease without HCC, suggesting that IL-10 may be needed for immunosuppression in the established and progressing tumor [118–120]. The chemokine CCL22 also expresses in a similar pattern with IL-10. As a highly expressed chemokine in HBV-positive HCC tumor cells, CCL22 promotes the tumorigenic and metastatic process by binding to its receptor CCR4 on the surface of Treg cells, consequently recruiting those immunosuppressive cells to the tumor microenvironment and promoting tumor cell escape from immune surveillance [32].

Many studies on HCC have determined the circulating levels or expression pattern in the liver tissue of cytokines and chemokines, but few of them examined both the serum and liver tissue simultaneously. The profiles of those soluble factors in these two compartments from HCC patients do not always align completely. For example, IL-6 plays important roles in tumor initiation but displays a lower level of expression in tumor tissue than in peritumoral tissue [114,115]. However, IL-6 is elevated in the serum of patients with HCC compared to patients with chronic liver disease or healthy controls, and continues to rise as HCC progresses [120–124]. Another example is IL-18, a member of the IL-1 family of cytokines, which has been reported to be present at increasing levels in the serum of patients with HCC compared to patients with cirrhosis or healthy controls [125,126]. However, while its presence in the diseased liver is higher than that in healthy controls, IL-18 expression in the tumor itself is lower than that in surrounding tissue that is often associated with inflammation and fibrosis [127,128].

Finally, not only does HBV play an important role in causing a chronic inflammatory condition via infection of hepatocytes, but it has also been shown to directly regulate the production of cytokines. For example, HBx is able to specifically induce the expression of, among other cytokines and chemokines, IL-6, IL-18, and CXCL12, which regulate hepatocyte proliferation and survival, immune cell function, and angiogenesis, indicating the broad spectrum of processes that HBx can modulate [129–131]. Another example is the production of IFNλ, IL-10, and IL-12 by monocyte-derived DCs in response to stimulation with HBsAg and HBcAg, again demonstrating the broad range of functionalities which can be modulated by HBV to enhance not only viral survival but also initiation and progression of HCC [132].

Growth factors and other soluble proteins

A large number of growth factors and other soluble proteins important for HCC initiation and progression have been identified and explored both clinically and experimentally. Many of these factors have proven to be of prognostic value, and the profiles of their presence correlate well with each other and with clinical manifestations. Similar to the cytokines and chemokines discussed above, they are intimately linked with the status of HBV presence for their expression at various stages of tumor initiation and progression, and perform a wide variety of functions to modulate the tumorigenic process (a selection of these factors is shown in Table 2; associated references are included in the online-only document ‘Supplemental References for Table 2’).

Table 2.

Selected growth factors, signaling mediators, and other proteins in HBV-associated HCC prognosis

| Soluble factor | Tissue type | Stage(s) evaluated | mRNA or protein | Conclusion | Supplemental reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ang-2 | Liver | HCC | Protein | Expression in tumor correlates with microvessel density; lower expression correlates with lower recurrence | 1 |

| COX-2 | Liver | HCC | Protein | Expression in tumor correlates with VEGF | 2 |

| CTGF | Liver | HCC | mRNA | Higher in tumor predicts bone metastases, poor survival after resection | 3–5 |

| Serum | Cirrhosis, HCC | Protein | Higher in cirrhotic patients than in HCC patients with cirrhosis, which are higher than healthy controls; decreasing serum levels with advancing HCC | 6 | |

| DKK1 | Serum | Chronic liver disease, HCC | Protein | Higher in HCC patients than chronic liver disease and healthy controls | 7 |

| EGFR | Serum | HCC | Protein | Higher in HCC patients than chronic liver disease and healthy controls, with enhanced levels with co-infection with HBV and HCV | 8 |

| HGF | Serum | Chronic liver disease, HCC | Protein | Higher in HCC and chronic HBV and HCV patients than healthy controls | 9 |

| IGF2 | Liver | Cirrhosis, HCC | Protein | Higher expression in tumor and cirrhotic tissue than in chronic hepatitis or healthy controls; correlates with HBV+ status; P3 transcript overexpressed in HCC, correlates with degree of differentiation, infiltration of serosa, tumor size, and HBV status | 10–16 |

| Serum | HCC | Protein | Higher in HCC patients than healthy controls | 16 | |

| MMP1 | Liver | HCC | Protein | High peritumoral predicts bone metastases | 3 |

| Serum | HCC | Protein | Higher in HCC patients than cirrhotic or healthy controls | 17 | |

| MMP9 | Liver | HCC | Protein | Lower expression correlates with lower recurrence | 1 |

| OPN | Liver | HCC | Protein | Expression in tumor correlates with capsular and venous invasion, lymph node metastasis, and worse prognosis; elevated expression predicts worse disease-free and overall survival | 18, 19 |

| Serum | Cirrhosis, HCC | Protein | Higher in HCC patients than cirrhotic or healthy controls; and both higher than healthy controls, and predictive of liver damage severity; elevated expression predicts tumor size and recurrence | 20–22 | |

| SHH | Liver | Chronic liver disease, HCC | Protein | Higher in HCC and chronic HBV and HCV patients than healthy controls | 23 |

| TGF-α | Liver | HCC | mRNA, protein | Higher expression in tumor and peritumor and in non-neoplastic HBsAg+ tissue than chronic HBV which is higher than in healthy tissue | 24–27 |

| Serum | Chronic liver disease, HCC | Protein | Higher in HCC patients than chronic liver disease and healthy controls | 28 | |

| TGF-β | Liver | HCC | Protein | Higher in HCC patients than healthy controls, higher in HBV+ patients than HBV− patients; higher in groups with tumor embolus of portal vein; higher expression of pSmad2 in HBV+ primary tumors than HBV− primary tumors; higher expression of pSmad2 in metastases than primary tumors | 29–31 |

| Serum | Chronic liver disease, HCC | Protein | Higher in HCC patients than chronic liver disease and healthy controls, with enhanced levels with co-infection with HBV and HCV | 8, 28 | |

| VEGF | Liver | HCC | Protein | Higher in tumor predicts worse clinical outcome | 1, 2, 32, 33 |

| Wnt-1 | Liver | HCC | Protein | Increased expression in HBV+ and HCV+ HCC; intratumoral expression correlated with increased recurrence | 34 |

Chen, ZB, Shen, SQ, Ding, YM et al. The angiogenic and prognostic implications of VEGF, Ang-1, Ang-2, and MMP-9 for hepatocellular carcinoma with background of hepatitis B virus. Med. Oncol. 2009; 26:365–371.

Cheng, ASL, Chan, HLY, To, KF et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 pathway correlates with vascular endothelial growth factor expression and tumor angiogenesis in hepatitis B virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. Int. J. Oncol. 2004; 24:853–860.

Xiang, ZL, Zeng, ZC, Tang, ZY et al. Potential prognostic biomarkers for bone metastasis from hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncologist 2011; 16:1028–1039.

Xiang, ZL, Zeng, ZC, Fan, J et al. Expression of connective tissue growth factor and interleukin-11 in intratumoral tissue is associated with poor survival after curative resection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2012; 39:6001–6006.

Gao, YB, Xiang, ZL, Zhou, LY et al. Enhanced production of CTGF and IL-11 from highly metastatic hepatoma cells under hypoxic conditions: an implication of hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis to bone. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2013; 139:669–679.

Gressner, OA, Fang, M, Li, H et al. Connective tissue growth factor (CTGF/CCN2) in serum is an indicator of fibrogenic progression and malignant transformation in patients with chronic hepatitis B infection. Clin. Chim. Acta 2013; 421:126–131.

Shen, Q, Fan, J, Yang, XR et al. Serum DKK1 as a protein biomarker for the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: a large-scale, multicentre study. Lancet Oncol. 2012; 13:817–826.

Divella R, Daniele, A, Gadaleta, C et al. Circulating transforming growth factor-β and epidermal growth factor receptor as related to virus infection in liver carcinogenesis. Anticancer Res. 2012; 32:141–145.

Hsia, CY, Huo, TI, Chiang, SY et al. Evaluation of interleukin-6, interleukin-10 and human hepatocyte growth factor as tumor markers for hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2007; 33:208–212. doi:10.1016/j.ejso.2006.10.036.

Lamas, E, Le Bail, B, Housset, C et al. Localization of insulin-like growth factor-II and hepatitis B virus mRNAs and proteins in human hepatocellular carcinomas. Lab. Invest. 1991; 64:98–104.

D’Errico, A, Grigioni, WF, Fiorentino, M et al. Expression of insulin-like growth factor II (IGF-II) in human hepatocellular carcinomas: an immunohistochemical study. Pathol. Int. 1994; 44:131–137.

Fiorentino, M, Grigioni, WF, Baccarini, P et al. Different in situ expression of insulin-like growth factor type II in hepatocellular carcinoma. An in situ hybridization and immunohistochemical study. Diagn. Mol. 1994; Pathol. 3:59–65.

Seo, JH, Park, BC. Expression of insulin-like growth factor II in chronic hepatitis B, liver cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho 1995; 22 Suppl 3:292–307.

Tang, SH, Yang, DH, Huang, W et al. Differential promoter usage for insulin-like growth factor-II gene in Chinese hepatocellular carcinoma with hepatitis B virus infection. Cancer Detect. Prev. 2006; 30:192–203.

Dong, ZZ, Yao, DF, Wu, W et al. [Correlation between epigenetic alterations in the insulin growth factor-II gene and hepatocellular carcinoma]. (Chinese) Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi 2012; 20:593–597

Dong, ZZ, Yao, M, Qian, J et al. [Abnormal expression of insulin-like growth factor-II and intervening of its mRNA transcription in the promotion of HepG2 cell apoptosis]. (Chinese) Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 2013; 93:892–896.

Yang, L, Rong, W, Xiao, T et al. Secretory/releasing proteome-based identification of plasma biomarkers in HBV-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci. China Life Sci. 2013; 56:638–646.

Xie, H, Song, J, Du, R et al. Prognostic significance of osteopontin in hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig. Liver Dis. 2007; 39:167–172.

Yu, MC, Lee, YS, Lin, SE et al. Recurrence and poor prognosis following resection of small hepatitis B-related hepatocellular carcinoma lesions are associated with aberrant tumor expression profiles of glypican 3 and osteopontin. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2012; 19 Suppl 3:S455–63.

Zhao, L, Li, T, Wang, Y et al. Elevated plasma osteopontin level is predictive of cirrhosis in patients with hepatitis B infection. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2008; 62:1056–1062.

Sun, J, Xu, HM, Zhou, HJ et al. The prognostic significance of preoperative plasma levels of osteopontin in patients with TNM stage-I of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2010; 136:1–7.

Shang, S, Plymoth, A, Ge, S et al. Identification of osteopontin as a novel marker for early hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2012; 55:483–490.

de Almeida Pereira, T, Witek, RP, Syn, WK et al. Viral factors induce Hedgehog pathway activation in humans with viral hepatitis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Lab. Invest. 2010; 90:1690–1703.

Hsia, CC, Axiotis, CA, Di Bisceglie, AM, and Tabor, E. Transforming growth factor-alpha in human hepatocellular carcinoma and coexpression with hepatitis B surface antigen in adjacent liver. Cancer 1992; 70:1049–1056.

Hsia, CC, Thorgeirsson, SS, and Tabor, E. Expression of hepatitis B surface and core antigens and transforming growth factor-alpha in “oval cells” of the liver in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Med. Virol. 1994; 43:216–221.

Yuan, F, Huang, P, Gao, M, and Gong, H. [Expression of transforming growth factor alpha and its relationship with HBV infection in hepatocellular carcinomas]. (Chinese) Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi 1999; 28:35–38.

Chung, YH, Kim, JA, Song, BC et al. Expression of transforming growth factoralpha mRNA in livers of patients with chronic viral hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer 2000; 89:977–982.

El-Tayeh, SF, Hussein, TD, El-Houseini, ME et al. Serological biomarkers of hepatocellular carcinoma in Egyptian patients. Dis. Markers 2012; 32:255–263.

Dong, ZZ, Yao, DF, Yao, M et al. Clinical impact of plasma TGF-beta1 and circulating TGF-beta1 mRNA in diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int. 2008; 7:288–295.

Lu, Y, Wu, LQ, Li, CS et al. Expression of transforming growth factors in hepatocellular carcinoma and its relations with clinicopathological parameters and prognosis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int. 2008; 7:174–178.

Yang, P, Li, QJ, Feng, Y et al. TGF-beta-miR-34a-CCL22 signaling-induced Treg cell recruitment promotes venous metastases of HBV-positive hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Cell 2012; 22:291–303.

Moon, JI, Kim, JM, Jung, GO et al. 2008. [Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) family members and prognosis after hepatic resection in HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma]. (Korean) Korean J Hepatol. 2008; 14:185–196.

Wang, C, Lu, Y, Chen, Y et al. Prognostic factors and recurrence of hepatitis Brelated hepatocellular carcinoma after argon-helium cryoablation: a prospective study. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 2009; 26:839–848.

Lee, HH, Uen, YH, Tian, YF et al. Wnt-1 protein as a prognostic biomarker for hepatitis B-related and hepatitis C-related hepatocellular carcinoma after surgery. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2009; 18:1562–1569.

Several growth factors and secreted proteins have been shown to be predictive for not only phenotypic properties but also ultimate prognosis for HCC patients. For example, VEGF, the growth factor classically known for its abilities to act on endothelial cells and induce angiogenesis, has been highly correlated with both microvessel density within the tumor and worse clinical outcome [92,93,133,134]. IGF2, a member of the insulin-like growth factor family with potent mitogenic effects, has been correlated with degree of differentiation, infiltration of serosa, size of tumor, and proliferative index of the tumor [135–141]. OPN, a protein known to be an important modulator of inflammatory cascades, has been shown to be predictive of worse disease-free and overall survival, as well as correlating with severity of liver damage, capsular infiltration, venous invasion, and lymph node metastases [142–146].

The functionality of several of these growth factors and related proteins in the context of HCC has also been explored in some detail, although comprehensive mechanistic understanding is still far from complete. TGF-β, a growth factor well-established to have both tumor-suppressive and tumor-enhancing properties depending on context, is an important example in the HBV-associated HCC microenvironment. During liver cancer progression, TGF-β production can be induced by multiple HBV proteins in transformed hepatocytes [32]. This leads to suppressed expression of the microRNA miR-34a, resulting in elevated expression of CCL22, which in turn promotes the accumulation of the immunosuppressive Treg population [32]. This immunosuppressive environment leads to enhanced tumor growth as well as intravenous metastasis of HBV-associated HCC [32]. Sonic Hedgehog (SHH), a ligand of the Hedgehog family, is expressed at higher levels in chronic HBV and HCC patients [147]. The SHH signaling cascade has been shown to promote fibrogenesis, angiogenesis, cell migration, anchorage-independent growth, and tumor development [147]. Finally, COX-2, an enzyme crucial for the biosynthesis of prostaglandins, has been shown to increase PGE2 expression and consequently VEGF production, leading to enhanced angiogenesis. This notion is corroborated by its elevated expression in the majority of HCC tissue samples and correlation with increases in both VEGF expression and microvessel density [92].

Finally, as with cytokines, HBV has been shown to directly regulate the production of growth factors and to interact with members of their signaling cascades. HBx promotes transcription of the third promoter of IGF2 via hypomethylation and the fourth promoter of IGF2 via interaction with Sp1 [148,149]. It also promotes transcription of TGF-β, VEGF, and YAP [150–152]. It has been shown to help shift TGF-β/Smad3 signaling from a cytostatic mechanism via phosphorylation of Smad3 at the C terminus to an oncogenic mechanism via JNK-mediated phosphorylation at the linker region [153]. It also enhances mTOR signaling through IKK, interacts with APC to promote Wnt/β-Catenin signaling, and stabilizes Gli1 to enhance Hedgehog signaling [151,154,155]. HBsAg also contributes to the same signaling processes, via both its PreS1 variant promoting the transcription of TGF-α and its up-regulation of LEF-1, consequently allowing it to accumulate in the nucleus and activate target gene transcription [156,157]. These data demonstrate a highly dynamic role for HBV not only in creating an environment where growth factor signaling can promote the tumorigenic process, but also directing interactions among these signaling cascades to further enhance the process.

MicroRNAs

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small 18–22 nucleotide sequences of non-coding RNA whose canonical function is to regulate gene expression and translation [158]. These miRNAs are potent effectors which can regulate a vast array of biological processes, including both cell-autonomous and non-cell-autonomous processes, and therefore modulate both the activity of tumor cells and the activity of their microenvironment. Dysregulation of miRNA expression and activity has been reported frequently in a variety of cancers, including liver cancer. miRNAs have been shown to modulate progression of HCC from the initial underlying liver disease event through oncogenic transformation and finally metastasis, with the potential to serve as biomarkers in circulation. In-depth discussions of the functional power of these miRNAs, and their multiplicity of targets and cumulative effects have been published in numerous recent reviews [158–163].

The physical microenvironment of HCC

Not only cellular factors and soluble mediators, but indeed the entire microenvironment consisting of its physical make-up and chemistry, including oxygen supply, caging collagen and resultant liver stiffness, pH, and availability of metabolic fuel such as glucose and amino acids, affects the growth and progression of HBV-associated HCC. While the analysis and discussion concerning all these factors are outside the scope of this review, several reports have reviewed these topics in depth, providing clear insights into both functional relevance and prognostic and therapeutic significance of these components of the tissue microenvironment in HCC [164–168].

THERAPEUTIC OPPORTUNITIES TARGETING THE MICROENVIRONMENT

As discussed earlier, mortality from HCC stands at a high level, with a five-year survival rate of only 30–40% [2]. Current treatment options for HCC include surgical resection, transplantation, ablation (via percutaneous ethanol administration or radiofrequencies), transarterial embolization (with chemotherapy or radioactive yttrium spheres), and some pharmacologic agents such as sorafenib [1]. With the large variety of cellular and non-cellular components of the microenvironment, therapies targeting the microenvironment are a promising new angle for treating this disease. Indeed, the demonstrated efficacy of sorafenib [169], which inhibits VEGF signaling, is an encouraging indication that these newly developed targeted therapies may indeed be efficacious treatments for HCC. Other potential targets include additional growth factor signaling pathways, as well as targeting soluble immune mediators via sequestration or administration, depending on the functional nature of those factors. One of the goals of such a tactic would be to skew the recruitment of immune mediators and/or their functionality. For example, treatment with an antagonist of CCR4 should reduce recruitment of Treg cells, and potentially result in a more robust antitumor immune response. Promotion of a robust antitumor immune response indeed is perhaps the most desirable outcome: the remarkable efficacy of T-cell immunotherapy through either engineering (chimeric antigen receptor therapy) or relieving the brakes on T-cell activity (anti-PD-1, anti-PD-L1, and anti-CTLA-4, which block interactions between inhibitory ligands and inhibitory receptors on T cells) has led to much excitement, having remarkable effects on melanoma and myeloma, as well as other cancers [170–175]. These results indicate the emergence of a new set of opportunities to extend these treatments to other cancers, such as HCC. The recent advances in the field of tumor immunology portend a powerful advantage in the fight against HCC should a greater understanding of both the microenvironment of the tumor and therapeutic manipulation of it be harnessed and utilized.

CONCLUSIONS

In contrast to a majority of solid tumors, HCC emerges from a chronically diseased liver associated with inflammation and fibrosis. Thus, the microenvironment for HCC initiation, progression, and metastasis is deemed to be highly dynamic and interactive with the involvement of many stromal cell types and soluble factors. Importantly, the nature of pathological characteristics of each HCC case and its associated signaling networks active in the tumorigenic process is likely to be heavily influenced by the biological nature of the etiological cause. In this context, hepatitis B has long been known as a critical etiological factor capable of inducing hepatocarcinogenesis in countries where chronic infection of HBV has been prevalent among the population, but its importance in continuing to modulate the tumorigenic process once a tumor emerges in the liver is becoming increasingly more evident in recent years. The interactions between HBV as the etiological factor and the evolving microenvironment in HCC will continue to be a prominent topic of research in the foreseeable future. Elucidation of predominant mechanisms and players in this crosstalk, and analyses to find areas of commonality and divergence in the dynamically evolving microenvironment between tumor and stromal cells, will be of great value in developing more advanced and targeted therapies. Such information will also become the basis of decision-making in diagnosis and treatment for the entire course of the disease, and will ultimately help alleviate the burden of this monstrous malignance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank members of the Wang Lab for helpful discussions related to this work.

FUNDING

This work was supported by grant CA154151 to XFW from the National Cancer Institute of the USA.

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available online at nsr.oxfordjournals.org.

References

- 1.Yang JD, Roberts LR. Hepatocellular carcinoma: a global view. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7:448–58. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2010.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Portolani N, Coniglio A, Ghidoni S, et al. Early and late recurrence after liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: prognostic and therapeutic implications. Ann Surg. 2006;243:229–35. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000197706.21803.a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, et al. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen CJ, Yang HI, Su J, et al. Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma across a biological gradient of serum hepatitis B virus DNA level. JAMA. 2006;295:65–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen CJ, Yang HI, Iloeje UH, The REVEAL-HBV Study Group Hepatitis B virus DNA levels and outcomes in chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2009;49:S72–84. doi: 10.1002/hep.22884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benhenda S, Cougot D, Buendia MA, et al. Hepatitis B virus X protein molecular functions and its role in virus life cycle and pathogenesis. Adv Cancer Res. 2009;103:75–109. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(09)03004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kew MC. Hepatitis B virus x protein in the pathogenesis of hepatitis B virusinduced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26(Suppl 1):144–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu L, Zhai X, Liu J, et al. Genetic variants in human leukocyte antigen/DP-DQ influence both hepatitis B virus clearance and hepatocellular carcinoma development. Hepatology. 2012;55:1426–31. doi: 10.1002/hep.24799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li S, Qian J, Yang Y, et al. GWAS identifies novel susceptibility loci on 6p21.32 and 21q21.3 for hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B virus carriers. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002791. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nishida N, Sawai H, Matsuura K, et al. Genome-wide association study confirming association of HLA-DP with protection against chronic hepatitis B and viral clearance in Japanese and Korean. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e39175. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Qahtani AA, Al-Anazi M, Abdo AA, et al. Genetic variation at -1878 (rs2596542) in MICA gene region is associated with chronic hepatitis B virus infection in Saudi Arabian patients. Exp Mol Pathol. 2013;95:255–8. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Qahtani AA, Al-Anazi MR, Abdo AA, et al. Genetic variation in interleukin 28B and correlation with chronic hepatitis B virus infection in Saudi Arabian patients. Liver Int. 2014;34:e208–16. doi: 10.1111/liv.12347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen K, Shi W, Xin Z, et al. Replication of genome wide association studies on hepatocellular carcinoma susceptibility loci in a Chinese population. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e77315. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang DK, Sun J, Cao G, et al. Genetic variants in STAT4 and HLA-DQ genes confer risk of hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2013;45:72–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.2483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim YJ, Kim HY, Lee JH, et al. A genome-wide association study identified new variants associated with the risk of chronic hepatitis B. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:4233–8. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Qahtani AA, Al-Anazi MR, Abdo AA, et al. Association between HLA variations and chronic hepatitis B virus infection in Saudi Arabian patients. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e80445. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gu X, Qi P, Zhou F, et al. +49G > A polymorphism in the cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 gene increases susceptibility to hepatitis B-related hepatocellular carcinoma in a male Chinese population. Hum Immunol. 2010;71:83–7. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2009.09.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kimkong I, Tangkijvanich P, Hirankarn N. Association of interferon-alpha gene polymorphisms with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Int J Immuno-genet. 2013;40:476–81. doi: 10.1111/iji.12055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tang S, Yuan Y, He Y, et al. Genetic polymorphism of interleukin-6 influences susceptibility to HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma in a male Chinese Han population. Hum Immunol. 2014;75:297–301. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qin LX. Inflammatory immune responses in tumor microenvironment and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Microenviron. 2012;5:203–9. doi: 10.1007/s12307-012-0111-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Bruggen P, Traversari C, Chomez P, et al. A gene encoding an antigen recognized by cytolytic T lymphocytes on a human melanoma. Science. 1991;254:1643–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1840703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boon T, Cerottini JC, Van den Eynde B, et al. Tumor antigens recognized by T lymphocytes. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:337–65. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.002005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Szabo SJ, Sullivan BM, Peng SL, et al. Molecular mechanisms regulating Th1 immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:713–58. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.140942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galon J, Costes A, Sanchez-Cabo F, et al. Type, density, and location of immune cells within human colorectal tumors predict clinical outcome. Science. 2006;313:1960–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1129139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tzeng HT, Tsai HF, Liao HJ, et al. PD-1 blockage reverses immune dysfunction and hepatitis B viral persistence in a mouse animal model. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e39179. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fu J, Xu D, Liu Z, et al. Increased regulatory T cells correlate with CD8 T-cell impairment and poor survival in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2328–39. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shen X, Li N, Li H, et al. Increased prevalence of regulatory T cells in the tumor microenvironment and its correlation with TNM stage of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2010;136:1745–54. doi: 10.1007/s00432-010-0833-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guidotti LG, Rochford R, Chung J, et al. Viral clearance without destruction of infected cells during acute HBV infection. Science. 1999;284:825–9. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5415.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoo YD, Ueda H, Park K, et al. Regulation of transforming growth factor-beta 1 expression by the hepatitis B virus (HBV) X transactivator. Role in HBV pathogenesis. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:388–95. doi: 10.1172/JCI118427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peng G, Li S, Wu W, et al. CD4+ CD25 +regulatory T cells correlate with chronic hepatitis B infection. Immunology. 2008;123:57–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02691.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stross L, Günther J, Gasteiger G, et al. Foxp3+ regulatory T cells protect the liver from immune damage and compromise virus control during acute experimental hepatitis B virus infection in mice. Hepatology. 2012;56:873–83. doi: 10.1002/hep.25765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang P, Li QJ, Feng Y, et al. TGF-beta-miR-34a-CCL22 signaling-induced Treg cell recruitment promotes venous metastases of HBV-positive hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:291–303. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu L, Yin W, Sun R, et al. Liver type I regulatory T cells suppress germinal center formation in HBV-tolerant mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:16993–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1306437110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steinman RM. The dendritic cell system and its role in immunogenicity. Annu Rev Immunol. 1991;9:271–96. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.09.040191.001415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Armstrong TD, Pulaski BA, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Tumor antigen presentation: changing the rules. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1998;46:70–4. doi: 10.1007/s002620050463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang AH, Sofola IO, Bufkin BL, et al. Coronary sinus pressure and arterial venting do not affect retrograde cardioplegia distribution. Ann Thorac Surg. 1994;58:1499–504. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(94)91943-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Colonna M, Trinchieri G, Liu YJ. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells in immunity. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1219–26. doi: 10.1038/ni1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Charles J, Chaperot L, Salameire D, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells and dermatological disorders: focus on their role in autoimmunity and cancer. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:16–23. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2010.0816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tang TJ, Vukosavljevic D, Janssen HLA, et al. Aberrant composition of the dendritic cell population in hepatic lymph nodes of patients with hepato-cellular carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2006;37:332–8. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chaput N, Conforti R, Viaud S, et al. The Janus face of dendritic cells in cancer. Oncogene. 2008;27:5920–31. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zou W, Machelon V, Coulomb-L’Hermin A, et al. Stromal-derived factor-1 in human tumors recruits and alters the function of plasmacytoid precursor dendritic cells. Nat Med. 2001;7:1339–46. doi: 10.1038/nm1201-1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hartmann E, Wollenberg B, Rothenfusser S, et al. Identification and functional analysis of tumor-infiltrating plasmacytoid dendritic cells in head and neck cancer. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6478–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perrot I, Blanchard D, Freymond N, et al. Dendritic cells infiltrating human non-small cell lung cancer are blocked at immature stage. J Immunol. 2007;178:2763–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.2763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ito T, Yang M, Wang YH, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells prime IL-10-producing T regulatory cells by inducible costimulator ligand. J Exp Med. 2007;204:105–15. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vincent IE, Zannetti C, Lucifora J, et al. Hepatitis B virus impairs TLR9 expression and function in plasmacytoid dendritic cells. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e26315. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yin XY, Lu MD, Lai YR, et al. Prognostic significances of tumor-infiltrating S-100 positive dendritic cells and lymphocytes in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:1281–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cai XY, Gao Q, Qiu SJ, et al. Dendritic cell infiltration and prognosis of human hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2006;132:293–301. doi: 10.1007/s00432-006-0075-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jenne CN, Kubes P. Immune surveillance by the liver. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:996–1006. doi: 10.1038/ni.2691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Iwai Y, Terawaki S, Ikegawa M, et al. PD-1 inhibits antiviral immunity at the effector phase in the liver. J Exp Med. 2003;198:39–50. doi: 10.1084/jem.20022235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.You Q, Cheng L, Kedl RM, et al. Mechanism of T cell tolerance induction by murine hepatic Kupffer cells. Hepatology. 2008;48:978–90. doi: 10.1002/hep.22395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hösel M, Quasdorff M, Wiegmann K, et al. Not interferon, but interleukin-6 controls early gene expression in hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatology. 2009;50:1773–82. doi: 10.1002/hep.23226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li H, Zheng HW, Chen H, et al. Hepatitis B virus particles preferably induce Kupffer cells to produce TGF-beta1 over proinflammatory cytokines. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44:328–33. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Boltjes A, Movita D, Boonstra A, et al. The role of Kupffer cells in hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus infections. J Hepatol. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wallace K, Burt AD, Wright MC. Liver fibrosis. Biochem J. 2008;411:1–18. doi: 10.1042/BJ20071570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sandler NG, Koh C, Roque A, et al. Host response to translocated microbial products predicts outcomes of patients with HBV or HCV infection. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1220–30. 1230.e1–3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tordjmann T, Soulie A, Guettier C, et al. Perforin and granzyme B lytic protein expression during chronic viral and autoimmune hepatitis. Liver. 1998;18:391–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0676.1998.tb00823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tang TJ, Kwekkeboom J, Laman JD, et al. The role of intrahepatic immune effector cells in inflammatory liver injury and viral control during chronic hepatitis B infection. J Viral Hepat. 2003;10:159–67. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2003.00412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kolios G, Valatas V, Kouroumalis E. Role of Kupffer cells in the pathogenesis of liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:7413–20. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i46.7413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Maeda S, Kamata H, Luo JL, et al. IKKβ couples hepatocyte death to cytokine-driven compensatory proliferation that promotes chemical hepatocarcinogenesis. Cell. 2005;121:977–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hagen TM, Huang S, Curnutte J, et al. Extensive oxidative DNA damage in hepatocytes of transgenic mice with chronic active hepatitis destined to develop hepatocellular carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:12808–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bility MT, Cheng L, Zhang Z, et al. Hepatitis B virus infection and immunopathogenesis in a humanized mouse model: induction of human-specific liver fibrosis and M2-like macrophages. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004032. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vanlandschoot P, Van Houtte F, Roobrouck A, et al. Hepatitis B virus surface antigen suppresses the activation of monocytes through interaction with a serum protein and a monocyte-specific receptor. J Gen Virol. 2002;83:1281–9. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-6-1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Oquendo J, Dubanchet S, Capel F, et al. Suppressive effect of hepatitis B virus on the induction of interleukin-1 beta and interleukin-6 gene expression in the THP-1 human monocytic cell line. Eur Cytokine Netw. 1996;7:793–800. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Roth S, Gong W, Gressner AM. Expression of different isoforms of TGF-beta and the latent TGF-beta binding protein (LTBP) by rat Kupffer cells. J Hepatol. 1998;29:915–22. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(98)80119-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vanlandschoot P, Roobrouck A, Van Houtte F, et al. Recombinant HBsAg, an apoptotic-like lipoprotein, interferes with the LPS-induced activation of ERK-1/2 and JNK-1/2 in monocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;297:486–91. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02243-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cheng J, Imanishi H, Morisaki H, et al. Recombinant HBsAg inhibits LPS-induced COX-2 expression and IL-18 production by interfering with the NFkappaB pathway in a human monocytic cell line, THP-1. J Hepatol. 2005;43:465–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shi B, Ren G, Hu Y, et al. HBsAg inhibits IFN-α production in plasmacytoid dendritic cells through TNF-α and IL-10 induction in monocytes. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e44900. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang S, Chen Z, Hu C, et al. Hepatitis B virus surface antigen selectively inhibits TLR2 ligand-induced IL-12 production in monocytes/macrophages by interfering with JNK activation. J Immunol. 2013;190:5142–51. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]