Abstract

Transplantation of skeletal myoblasts (SMs) has been investigated as a potential cardiac cell therapy approach. SM are available autologously, predetermined for muscular differentiation and resistant to ischemia. Major hurdles for their clinical application are limitations in purity and yield during cell isolation as well as the absence of gap junction expression after differentiation into myotubes. Furthermore, transplanted SMs do not functionally or electrically integrate with the host myocardium.

Here, we describe an efficient method for isolating homogeneous SM populations from neonatal mice and demonstrate persistent gap junction expression in an engineered tissue. This method resulted in a yield of 1.4 × 108 high-purity SMs (>99% desmin positive) after 10 days in culture from 162.12 ± 11.85 mg muscle tissue. Serum starvation conditions efficiently induced differentiation into spontaneously contracting myotubes that coincided with loss of gap junction expression.

For mechanical conditioning, cells were integrated into engineered tissue constructs. SMs within tissue constructs exhibited long term survival, ordered alignment, and a preserved ability to differentiate into contractile myotubes. When the tissue constructs were subjected to passive longitudinal tensile stress, the expression of gap junction and cell adherence proteins was maintained or increased throughout differentiation.

Our studies demonstrate that mechanical loading of SMs may provide for improved electromechanical integration within the myocardium, which could lead to more therapeutic opportunities.

Keywords: Skeletal myoblast cell, Connexin, Engineered tissue construct, Cardiac cell therapy

1. Introduction

Cell transplantation strategies for tissue repair have been explored with an increasing focus on cardiovascular disease, due to its global significance as the primary cause of death [1,2]. With the hope of developing an alternative for heart transplantation, which is currently the only therapeutic option for end stage heart failure [3], cell transplantation strategies are the focus of intense investigation at both the pre-clinical [4] and clinical [5] levels.

For over a decade, reports on the use of various cell types for cardiac repair and regeneration have been published [6]. These include trials with skeletal myoblasts (SMs) [7]. SMs were initially considered to represent an attractive option for cardiac cell therapy due to their myogenic and contractile phenotype, availability for autologous transplantation, high proliferative capacity in vitro, and their resistance to ischemia [8]. SMs were the first cell type to be used in clinical studies [9–11], in which they were shown to improve post-infarct heart function, but could also cause ventricular arrhythmias [12]. Electrical isolation of transplanted SMs was caused by the lack of intercellular communication with host cardiomyocytes [13]. The enhancement of gap junctional communication through connexin43 (Cx43) expression, which is typically decreased during differentiation of SMs [14], has been achieved by gene transfer [15] and cyclic stretching [16]. Transplantation of genetically modified SMs expressing Cx43 was shown to prevent arrhythmia [17]. However, other challenges for the application of cell transplantation strategies whether they involve SMs or not remain, including poor cell retention and survival [18].

Recently, we reported transplantation of SM-based engineered tissue constructs (ETC) for propagation of atrio-ventricular electrical conduction in a rat model [19]. Our experiments showed promising long-term results with respect to survival and retention of SM within transplanted ETCs and the conservation of some important electrophysiological properties if this form of treatment were to be applied to humans with complete heart block.

In the present study, we extend this work by improving the cell-to-cell communication characteristics of a SM-based ETC.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Myoblast isolation and culture

Neonatal C57BL/6 mice were euthanized and the limb muscle tissue was harvested for SM isolation as described previously [20]. Tissue samples were further processed by incubation in 0.2% collagenase type IV (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany), 2.4 IU/ml dispase (Invitrogen) and 3 mM calcium chloride (Sigma–Aldrich, Munich, Germany) in PBS. Tissue debris was removed using a 70 μm cell strainer (BD Biosciences, Heidelberg, Germany). Cells were cultured in isolation medium consisting of Ham's-F10 medium (Invitrogen), supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Invitrogen) and 2.5 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF, PeproTech, Hamburg, Germany) at a density of 1 × 105 cells/cm2 on collagen-coated plates (5 μg/cm2 type I colla gen, Invitrogen). These pre-plating steps were performed sequentially after 1, 2, 18 and 48 h of incubation. After the final pre-plating step, cells in suspension were discarded and adherent cells were detached by incubation with 0.05% trypsin/53 mM EDTA (Invitrogen) and then expanded using growth medium consisting of 40% Ham's-F10 medium, 40% Dulbecco's modified eagle medium (DMEM, Invitrogen) supplemented with 20% FBS and 2.5 ng/ml bFGF. All media were supplemented with penicillin/streptomycin (1:100, Invitrogen) and fungizone (1:1000; Invitrogen). Cells were passaged every other day at a ratio of 1:3, including a 15-min pre-plating step to remove contaminating cells. On day 7 of expansion (day 10 after cell isolation) cells at 80% confluence were differentiated by changing culture conditions to differentiation medium, which consisted of DMEM with 2% horse serum (PAA, Coelbe, Germany). Differentiation medium was changed daily for 14 days.

2.2. Fabrication of engineered tissue constructs

For the fabrication of ETCs, a previously published method [19] was modified. Briefly, the supportive matrix was prepared by mixing ice cold isolation medium, collagen (type I, 5 mg/ml), 0.1 M NaOH (Sigma–Aldrich) and Geltrex (Invitrogen) at a ratio of 3:3:1:1. Defined numbers of SMs were re-suspended in 200 μl isolation medium and mixed with 500 μl of the premixed matrix. The resulting cell-matrix suspension was cast into the molds. As a control (non-preconditioned ETC) the cell-matrix mixture was poured directly on a cell culture dish (BD Biosciences). The tissue constructs were warmed to 37 °C and incubated in isolation medium for 3 days, followed by incubation in differentiation medium for 11 days.

2.3. Immunohistochemistry

Cells from expansion (d10) and differentiation culture (d14–d24) were transferred onto collagen coated (5 μg/cm2 collagen type I) microscope cover slips. After fixation (methanol, Sigma–Aldrich) and permeabilization (0.3% Triton X-100 (Sigma–Aldrich) in PBS (Invitrogen), the samples were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA, PAA) and stained with primary antibodies against desmin, N-cadherin (N-Cad), connexin40 (Cx40), connexin43 (Cx43), connexin45 (Cx45), α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), skeletal myosin light chain (MyL), dystrophin and α-actinin2 (ACTN2) or a-actinin3 (ACTN3) diluted in PBS containing 1% BSA. Primary antibodies were detected with species matched AlexaFluor conjugated secondary antibodies (Supplementary material) diluted in 1% BSA in combination with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Invitrogen).

For immunohistochemistry, ETCs of d3 and d14 differentiated SMs were embedded into Tissue Tek OCT (Sakura, Staufen, Germany) and snap frozen in 2-methylbutane (Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany). Sections (10 lm) were fixed, permeabilized and stained using anti-desmin, anti-N-Cad, anti-Cx40, anti-Cx43, anti-Cx45, anti-α-SMA, anti-MyL, anti-dystrophin and anti-ACTN2/3 antibodies (Supplemental material).

Images were acquired using an Axiovert 200 microscope equipped with a DFW-X710 Sony color digital camera (Sony, Berlin, Germany) and Axiovision 4.3 software (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany).

2.4. Flow cytometry

For flow cytometric phenotype analysis SMs were harvested on day 3 and day 10. The cells were fixed, permeabilized and incubated with anti-desmin antibody diluted in PBS containing 1% BSA. Subsequently, cells were incubated with fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibody (Supplemental material) and analyzed on a FACSCalibur cytometer with Cell Quest Pro 6.0 software (BD Biosciences).

2.5. Immunoblot analysis

Immunoblot analyses were performed as described before with the following modifications [19]. Total protein extracts were separated by SDS–PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Braunschweig, Germany, Supplemental material). After blocking with 5% non-fat milk suspended in T-PBS (0.1% Tween20, Sigma–Aldrich), the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies (desmin, Cx43, Cx45, Cx40, N-Cad, N-CAM and β-actin in 1% non-fat milk, Supplemental material) at 4 °C overnight. Horseradish peroxidase conjugated secondary antibodies (Supplemental material) and the ECL kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used for visualization. Densitometric analysis was performed with ImageJ 1.37 software (National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

2.6. Statistical analysis

Numeric data are expressed as mean ± one standard deviation. Statistical analyses were performed using the Sigmastat software package (release 12, Systat Software, San Jose, CA, USA). Data derived from immunoblot densitometry were tested by two-way repeated measure ANOVA followed by a Holm-Sidak post-hoc test for multiple comparisons. A two-tailed probability value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Isolation of skeletal myoblast cells

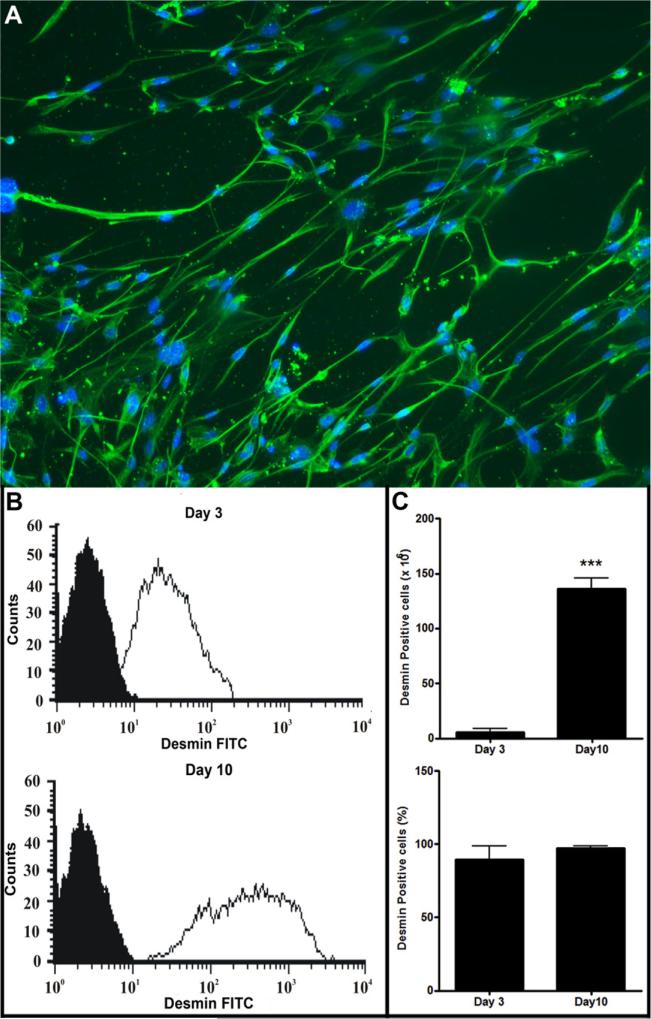

SM isolations from two animals yielded at 162.12 ± 11.85 mg tissue and 12.37 ± 2.10 × 106 cells in the primary isolate (n = 5). Three pre-plating steps and 48 h of incubation diminished the total cell number to approximately 50%. A majority of remaining adherent cells (Supplemental material) showed the typical spindle shaped morphology of SM. Immunocytochemistry showed a majority of cells were positive for desmin (Fig. 1). This was confirmed and quantified by flow cytometry where 89.5 ± 4% (n = 5) of cells were desmin positive (Fig. 1). After 10 days of expansion, a yield of 140.20 ± 11.45 × 106 cells was achieved with even higher purity as determined by desmin staining (97.1 ± 0.1%; n = 5).

Fig. 1.

Skeletal myoblast (SM) isolations from neonatal mice. (A) Immunocytochemical staining of SMs after seven days of cell culture for desmin (green) and DAPI (blue). Scale bar: 50 μm. Flow cytometric analysis of SMs after pre-plating (d3) and culture expansion (d10). Desmin: white histogram; Isotype control: black histogram. (B) Yield of total cells and ratio of desmin positive cells after pre-plating (d3) and culture expansion (d10, ***p < 0.0001; n = 5). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.2. Characterization of skeletal myoblast cells and myogenic differentiation

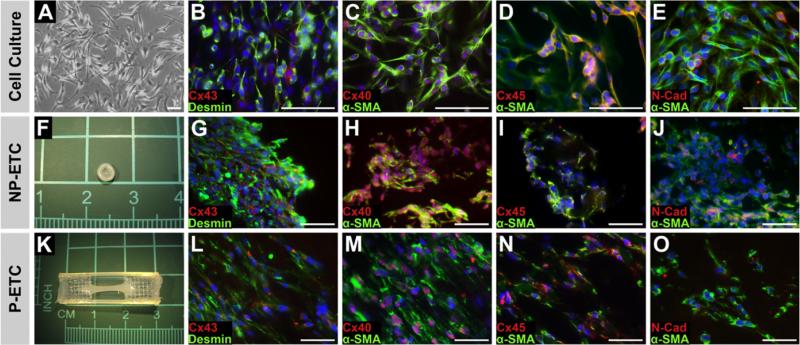

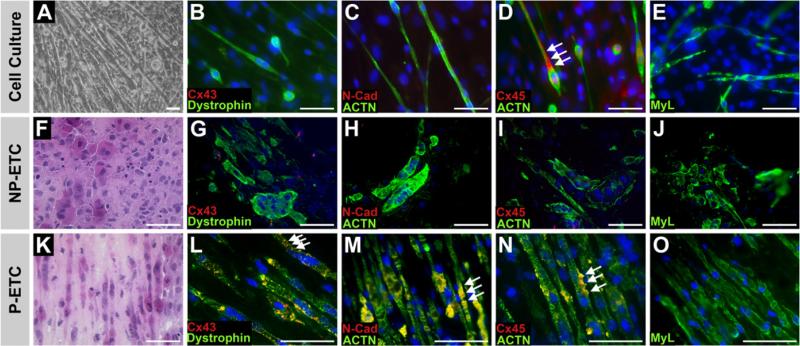

The majority of SMs (>80%) cultured under growth conditions expressed proteins necessary for mechanical (N-Cad) and electrical integration (Cx40, Cx43 and Cx45), as well as α-SMA (Fig. 2). When cells were subjected to serum starvation, distinct morphological changes were observed. After 14 days, SM fused and formed multi-nucleated myotubes (Fig. 3), showing spontaneously contracting clusters (Supplementary video 1). The immunocytochemical analysis of cells on d14 of incubation under differentiation conditions demonstrated a loss of expression of N-Cad, Cx43 and Cx45. Under growth conditions ACTN, dystrophin and MyL were widely expressed (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Skeletal myoblasts in cell culture and tissue constructs before differentiation Cell culture (A–E), non-preconditioned engineered tissue constructs (NP-ETCs (F–J)) and preconditioned engineered tissue constructs (P-ETCs) after three days in isolation medium (K–O). Bright field microscopy images (A) and macroscopic images (F,K). Immunostaining for desmin or α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) visualized in green, as indicated, in combination with connexin40 (Cx40), connexin43 (Cx43), connexin45 (Cx45) or N-cadherin (N-Cad) visualized in red, as indicated. Nuclear staining: DAPI (blue). Scale bar: 50 lm. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Fig. 3.

Skeletal myoblasts in cell culture and tissue constructs after differentiation cell culture (A–E), non-preconditioned engineered tissue construct (NP-ETC, F–J) and preconditioned engineered tissue construct (P-ETC, K–O) after 14 days in differentiation medium. Bright field microscopy images of cell culture (A) and H&E staining of ETC sections (F,K). Immunostaining of dystrophin, α-actinin (ACTN) or skeletal myosin light chain (MyL) visualized in green, as indicated, in combination with connexin43 (Cx43), connexin45 (Cx45) or N-cadherin (N-Cad) visualized in red as indicated. Nuclear staining: DAPI (blue). Arrows point to locations of Cx43 (L); N-Cad (M) and Cx45 expression (D,N). Scale bar: 50 μm. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.3. Engineered tissue construct morphology

At day 10 after isolation (passage 3), SMs from culture expansion (2–6 × 106 cells per ETC; Supplemental material) were used for the ETC fabrication. The application of 5 × 106 cells per ETC resulted in a homogeneous and longitudinal alignment of the myotubes. The NP-ETC showed a random orientation of cells (Fig. 3).

3.4. Engineered tissue construct characterization and differentiation

Both ETCs (P-ETC and NP-ETC) were analyzed for changes in protein expression before and after differentiation. Applying growth conditions, both ETCs were positive for desmin, N-Cad, α-SMA, Cx40, Cx43 and Cx45 (Fig. 2).

After 14 days of differentiation condition, P-ETCs were found to maintain or increase expression of N-Cad, Cx43, and Cx45 (Fig. 3) when compared to growth conditions. In addition, expression of the differentiation markers dystrophin and MyL were increased in P-ETCs.

When NP-ETCs were subjected to differentiation conditions, the expression of desmin was retained (data not shown) whereas expression of Cx43, Cx45 and N-Cad was not detectable. The expression of dystrophin and MyL was reduced in comparison to the P-ETCs (Fig. 3).

3.5. Effect of passive mechanical loading on gap junction and adhesion protein expression

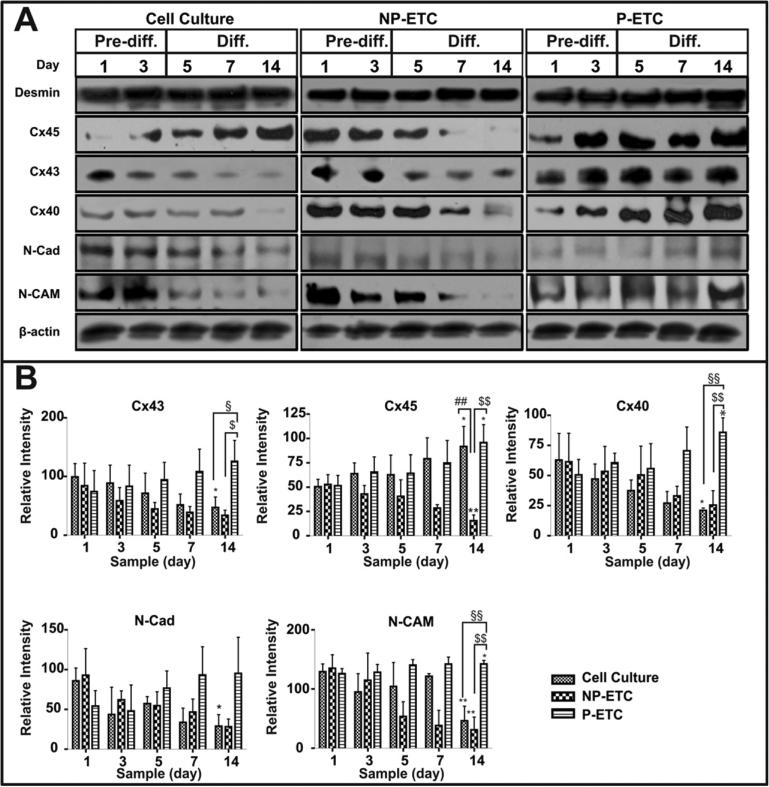

Samples from cell culture SMs, P-ETCs and NP-ETCs from either day 1 and 3 (growth conditions) or day 5, 7 and 14 (differentiation conditions) were further investigated by immunoblot analyses (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Expression of gap junction and adherens proteins in skeletal myoblasts from cell culture and tissue constructs before and after differentiation. (A) Mechanical preconditioning increases the expression of gap junction proteins and adhesion proteins essential for electromechanical coupling. Immunoblot analyses of desmin, connexin45 (Cx45), connexin43 (Cx43), connexin40 (Cx40), N-cadherin (N-Cad) and N-CAM expression for samples from cell culture (left panel), NP-ETC (middle panel) or PETC (right panel) on day 1, 3, 5, 7 and 14. b-actin served as loading control. (B) The intensities of specific bands from immunoblot analyses were quantified by densitometry (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, represents d1 versus d14 in each group; §p < 0.05, §§p < 0.01, §§§p < 0.001, represents P-ETC versus cell culture at d14; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001, represents NP-ETC versus cell culture at d14; $p < 0.05, $$p < 0.01, $$$p < 0.001, represents P-ETC versus NP-ETC at d14; n = 3).

Desmin expression remained constant throughout the differentiation process under all conditions.

Expression levels of gap and tight junction proteins in cultured cells decreased from d1 before differentiation to d14 after differentiation for Cx40 (3.0x, p = 0.0310), Cx43 (2.1x, p = 0.0358), N-Cad (3.0x, p = 0.0102) and N-CAM (2.8x, p = 0.0067), whereas Cx45 increased (1.8x, p = 0.0309). For cells in NP-ETCs, expression levels decreased for Cx45 (3.4x, p = 0.0052) and increased for N-CAM (4.3x, p = 0.0046) and N-Cad (3.3x, p = 0.0319). Cells in P-ETCs showed an increase in expression levels of Cx40 (1.7x, p = 0.0254), Cx45 (1.9x, p = 0.0228) and N-CAM (1.1x, p = 0.0496) from d1 to d14.

No difference in the expression of gap junction and adherens proteins between cells from culture, NP-ETCs and P-ETCs was detectable at day 1.

On day 14, the expression of Cx45 was lower for cells in culture when compared to cells in NP-ETCs (5.9x, p = 0.0035). Cells from cultures showed higher expression levels for Cx40 (4.1x, p = 0.0008), Cx43 (2.7x, p = 0.0266) and N-CAM (3.1x, p = 0.0027) when compared to cells in P-ETCs. Cells from P-ETCs showed higher expression levels for Cx40 (3.4x, p = 0.0035), Cx43 (3.7x, p = 0.0121), Cx45 (6.2x, p = 0.0020) and N-CAM (4.6x, p = 0.0010) compared to those in NP-ETCs.

4. Discussion

Our protocol for the isolation of murine SMs relies on the differential adhesion properties of cell populations derived from neonatal skeletal muscle tissue.

Primary cell isolates are heterogeneous in nature [22]. We confirmed this heterogeneity in the cells by virtue of their irregular morphology with an apparent predominance of fibroblast-like cells. The serial pre-plating steps and subsequent incubation on collagen-coated cell culture dishes, we observed enrichment of SMs (see Supplemental material). Immunocytochemistry and flow cytometry for the myogenic marker desmin [23] confirmed this increased purity (89.5% ± 4%) in our cell population (Fig. 1). Further expansion increased homogeneity to >97% and resulted in an overall yield of 1.4 × 108 cells derived from two neonatal mice (162.12 ± 11.85 mg tissue) within 10 days, representing a remarkable purification and expansion efficiency of SM.

The generation of defined and homogeneous cells is of foremost importance to achieve comparable and reproducible results; thereby, allowing for the unambiguous mechanistic conclusions about possible therapeutic effects.

The cell culture expanded SMs were characterized by immunocytochemistry before and after the initiation of myogenic differentiation by serum starvation. The expression of desmin was nearly ubiquitous under both growth and differentiation conditions, confirming the absence of contaminating cell types.

In conventional 2-D cell cultures, applying the growth conditions that were permissive for SM proliferation and restrictive for differentiation into myotubes, the cells showed high levels of expression for proteins that are essential in mechanical and electrical cell-to-cell interaction. Our studies demonstrate the potential of these methods to create tissues capable of functionally integrating into host myocardial tissues.

When the cells were subjected to serum starvation conditions, formation of multinucleated, spontaneously contracting myotubes were observed (Supplementary video 1). Immunocytochemical analyses showed a loss of adherens and gap junction protein expression. At the same time, dystrophin, ACTN and MyL were widely expressed, reflecting maturation of SMs into myotubes.

SM incorporated within NP-ETCs showed comparable results under growth conditions. However, when NP-ETCs were subjected to differentiation conditions, there was no detectable expression of Cx43 or N-Cad by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 3) or immunoblot analyses (Fig. 4). On the other hand, there was increased expression of dystrophin, ACTN and MyL.

Consistent with SMs in cell cultures and NP-ETCs, cells in P-ETCs retained expression of the myogenic marker desmin and the efficient differentiation into myotubes was confirmed by dystrophin, ACTN and MyL expression as well as the presence of spontaneously contracting myotubes (Supplementary video 2). Interestingly, the immunoblot analysis of P-ETCs under differentiation conditions showed significantly higher expression of Cx43 and Cx40 when compared to cultured SMs and those in NP-ETCs, which reflects the potential for appropriate electromechanical coupling by gap junction formation. Furthermore, immunoblot analyses showed constant levels of N-Cad and N-CAM during differentiation. Both of these proteins are necessary for cell-cell interactions, adhesion and myoblast fusion [24]; suggesting the potential for functional integration after transplantation.

These results directly address two key concerns about the efficacy and safety of SM transplantation as a therapeutic option for treatment of ischemic heart disease. Intra-myocardial delivery of cells directly into the site of infarction has been shown to result in poor cell survival and retention [25,26]. Apoptosis due to local ischemia and inflammation in the host tissue as well as wash-out effects after injection are considered as the main reason for the cell loss [27]. Embedding the cells into a supportive matrix prior to transplantation may provide an optimal delivery platform to overcome the latter obstacle. The feasibility of this approach has been validated in various animal studies [28].

The second fundamental concern for a cell transplantation approach revolves around the therapeutic potential of the cells. Here, functional integration of transplanted cells into the site of injury is of significant importance, especially in a complex organ like the heart, with its highly orchestrated interactions between the conduction system and the working myocardium [29]. It has been shown that expression of proteins necessary for cardiac electrical coupling is decreased during differentiation of myoblasts to more contractile myotubes, which results in the potential for ventricular arrhythmia after transplantation [30].

There have been numerous publications reporting methods to increase expression of gap junction proteins in SMs to reduce the arrhythmogenic potential of transplanted cells. For instance, transgenic over-expression of Cx43 [17,31] or targeted knock-down of regulator miRNA [32] resulted in significant improvement of heart function and reduction of post-transplantational arrhythmia.

Since the transgenic manipulation of donor cells is not ideal for clinical cell therapy, non-transgenic approaches have been studied extensively, including successful manipulation of Cx43 expression by chemical [33], electrical [34] and mechanical [19,35] conditioning. Mechanical forces between cells are transmitted to some extent via adherens junctions and transduced through integrins into proportionate cellular responses regulating growth and survival through altered gene expression [36,37]. Directional mechanical forces increase the rigidity of the extracellular matrix, triggering internal cellular signals modulating cell motility and tissue morphogenesis [38]. Related to our work, it has been shown that directional mechanical force is essential for the formation of structurally organized muscle tissue [39]. This leads to distinctly different SM gene expression patterns in 3-D cultures compared to conventional 2-D cultures [40].

Our approach of seeding highly-purified populations of SMs into a 3-D hydrogel matrix without the need for trans-genetically enhancing expression of gap junction proteins represents an improvement in the clinical utility of SMs as a cardiac therapeutic cell type. It remains to be shown if the presented results hold true in an in vivo transplantation model.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Poornima Sureshkumar and Karthick Natarajan for editorial assistance.

Funding

This work was supported by the Center of Molecular Medicine Cologne, University of Cologne.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.05.016.

References

- 1.Bui AL, Horwich TB, Fonarow GC. Epidemiology and risk profile of heart failure. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2010 doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2010.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO The global burden of disease: 2004 update. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nicolini F, Gherli T. Alternatives to transplantation in the surgical therapy for heart failure. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2009;35:214–228. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dowell JD, Rubart M, Pasumarthi KB, Soonpaa MH, Field LJ. Myocyte and myogenic stem cell transplantation in the heart. Cardiovasc. Res. 2003;58:336–350. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(03)00254-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Menasche P. Cardiac cell therapy: lessons from clinical trials. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laflamme MA, Murry CE. Heart regeneration. Nature. 2011;473:326–335. doi: 10.1038/nature10147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murry CE, Wiseman RW, Schwartz SM, Hauschka SD. Skeletal myoblast transplantation for repair of myocardial necrosis. J. Clin. Invest. 1996;98:2512–2523. doi: 10.1172/JCI119070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Menasche P. Skeletal myoblasts and cardiac repair. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2008;45:545–553. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Menasche P, Hagege AA, Scorsin M, Pouzet B, Desnos M, Duboc D, Schwartz K, Vilquin JT, Marolleau JP. Myoblast transplantation for heart failure. Lancet. 2001;357:279–280. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03617-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Menasche P, Alfieri O, Janssens S, McKenna W, Reichenspurner H, Trinquart L, Vilquin JT, Marolleau JP, Seymour B, Larghero J, Lake S, Chatellier G, Solomon S, Desnos M, Hagege AA. The myoblast autologous grafting in ischemic cardiomyopathy (MAGIC) trial: first randomized placebo-controlled study of myoblast transplantation. Circulation. 2008;117:1189–1200. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.734103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hagege AA, Marolleau JP, Vilquin JT, Alheritiere A, Peyrard S, Duboc D, Abergel E, Messas E, Mousseaux E, Schwartz K, Desnos M, Menasche P. Skeletal myoblast transplantation in ischemic heart failure: long-term follow-up of the first phase I cohort of patients. Circulation. 2006;114:I108–I113. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.000521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Menasche P, Hagege AA, Vilquin JT, Desnos M, Abergel E, Pouzet B, Bel A, Sarateanu S, Scorsin M, Schwartz K, Bruneval P, Benbunan M, Marolleau JP, Duboc D. Autologous skeletal myoblast transplantation for severe postinfarction left ventricular dysfunction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2003;41:1078–1083. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leobon B, Garcin I, Menasche P, Vilquin JT, Audinat E, Charpak S. Myoblasts transplanted into rat infarcted myocardium are functionally isolated from their host. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:7808–7811. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1232447100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hagege AA, Carrion C, Menasche P, Vilquin JT, Duboc D, Marolleau JP, Desnos M, Bruneval P. Viability and differentiation of autologous skeletal myoblast grafts in ischaemic cardiomyopathy. Lancet. 2003;361:491–492. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12458-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abraham MR, Henrikson CA, Tung L, Chang MG, Aon M, Xue T, Li RA, B OR, Marban E. Antiarrhythmic engineering of skeletal myoblasts for cardiac transplantation. Circ. Res. 2005;97:159–167. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000174794.22491.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iijima Y, Nagai T, Mizukami M, Matsuura K, Ogura T, Wada H, Toko H, Akazawa H, Takano H, Nakaya H, Komuro I. Beating is necessary for transdifferentiation of skeletal muscle-derived cells into cardiomyocytes. FASEB J. 2003;17:1361–1363. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-1048fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roell W, Lewalter T, Sasse P, Tallini YN, Choi BR, Breitbach M, Doran R, Becher UM, Hwang SM, Bostani T, von Maltzahn J, Hofmann A, Reining S, Eiberger B, Gabris B, Pfeifer A, Welz A, Willecke K, Salama G, Schrickel JW, Kotlikoff MI, Fleischmann BK. Engraftment of connexin 43-expressing cells prevents post-infarct arrhythmia. Nature. 2007;450:819–824. doi: 10.1038/nature06321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang M, Methot D, Poppa V, Fujio Y, Walsh K, Murry CE. Cardiomyocyte grafting for cardiac repair:graft cell death and anti-death strategies. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2001:907–921. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choi YH, Stamm C, Hammer PE, Kwaku KF, Marler JJ, Friehs I, Jones M, Rader CM, Roy N, Eddy MT, Triedman JK, Walsh EP, McGowan FX, Jr., del Nido PJ, Cowan DB. Cardiac conduction through engineered tissue. Am. J. Pathol. 2006;169:72–85. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rando TA, Blau HM. Primary mouse myoblast purification characterization and transplantation for cell-mediated gene therapy. J. Cell Biol. 1994;125(6):1275–1287. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.6.1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rando TA, Blau HM. Primary mouse myoblast purification, characterization, and transplantation for cell-mediated gene therapy. J. Cell Biol. 1994;125:1275–1287. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.6.1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaufman SJ, Foster RF. Replicating myoblasts express a muscle-specific phenotype. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1988;85:9606–9610. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.24.9606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mege RM, Goudou D, Diaz C, Nicolet M, Garcia L, Geraud G, Rieger F. N-cadherin and N-CAM in myoblast fusion: compared localisation and effect of blockade by peptides and antibodies. J. Cell Sci. 1992;103(Pt 4):897–906. doi: 10.1242/jcs.103.4.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blocklet D, Toungouz M, Berkenboom G, Lambermont M, Unger P, Preumont N, Stoupel E, Egrise D, Degaute JP, Goldman M, Goldman S. Myocardial homing of nonmobilized peripheral-blood CD34+ cells after intracoronary injection. Stem Cells. 2006;24:333–336. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hofmann M, Wollert KC, Meyer GP, Menke A, Arseniev L, Hertenstein B, Ganser A, Knapp WH, Drexler H. Monitoring of bone marrow cell homing into the infarcted human myocardium. Circulation. 2005;111:2198–2202. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000163546.27639.AA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pagani FD, DerSimonian H, Zawadzka A, Wetzel K, Edge AS, Jacoby DB, Dinsmore JH, Wright S, Aretz TH, Eisen HJ, Aaronson KD. Autologous skeletal myoblasts transplanted to ischemia-damaged myocardium in humans. Histological analysis of cell survival and differentiation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2003;41:879–888. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eschenhagen T, Zimmermann WH. Engineering myocardial tissue. Circ. Res. 2005;97:1220–1231. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000196562.73231.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buckberg GD, Coghlan HC, Torrent-Guasp F. The structure and function of the helical heart and its buttress wrapping. VI. Geometric concepts of heart failure and use for structural correction. Semin. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2001;13:386–401. doi: 10.1053/stcs.2001.29959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Makkar RR, Lill M, Chen PS. Stem cell therapy for myocardial repair: is it arrhythmogenic? J Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2003;42:2070–2072. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fernandes S, van Rijen HV, Forest V, Evain S, Leblond AL, Merot J, Charpentier F, de Bakker JM, Lemarchand P. Cardiac cell therapy: overexpression of connexin43 in skeletal myoblasts and prevention of ventricular arrhythmias. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2009;13:3703–3712. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00740.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li YG, Zhang PP, Jiao KL, Zou YZ. Knockdown of microRNA-181 by lentivirus mediated siRNA expression vector decreases the arrhythmogenic effect of skeletal myoblast transplantation in rat with myocardial infarction. Microvasc. Res. 2009;78:393–404. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2009.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Du WJ, Li JK, Wang QY, Hou JB, Yu B. Lithium chloride preconditioning optimizes skeletal myoblast functions for cellular cardiomyoplasty in vitro via glycogen synthase kinase-3beta/beta-catenin signaling. Cells Tissues Organs. 2009;190:11–19. doi: 10.1159/000167699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shafy A, Lavergne T, Latremouille C, Cortes-Morichetti M, Carpentier A, Chachques JC. Association of electrostimulation with cell transplantation in ischemic heart disease. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2009;138:994–991001. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee SW, Kang HJ, Lee JY, Youn SW, Won JY, Kim JH, Lee HC, Lee EJ, Oh SI, Oh BH, Park YB, Kim HS. Oscillating pressure treatment upregulates connexin43 expression in skeletal myoblasts and enhances therapeutic efficacy for myocardial infarction. Cell Transplant. 2009;18:1123–1135. doi: 10.3727/096368909X12483162196809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gomez GA, McLachlan RW, Yap AS. Productive tension: force-sensing and homeostasis of cell-cell junctions. Trends Cell Biol. 2011;21:499–505. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang N, Tytell JD, Ingber DE. Mechanotransduction at a distance: mechanically coupling the extracellular matrix with the nucleus. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009;10:75–82. doi: 10.1038/nrm2594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leckband DE, le Duc Q, Wang N, de Rooij J. Mechanotransduction at cadherin-mediated adhesions. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2011;23:523–530. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang H, Landmann F, Zahreddine H, Rodriguez D, Koch M, Labouesse M. A tension-induced mechanotransduction pathway promotes epithelial morphogenesis. Nature. 2011;471:99–103. doi: 10.1038/nature09765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bian W, Bursac N. Tissue engineering of functional skeletal muscle: challenges and recent advances. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Mag. 2008;27:109–113. doi: 10.1109/MEMB.2008.928460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.