Abstract

Abnormal behavior, ranging from motor stereotypies to self-injurious behavior, has been documented in captive nonhuman primates, with risk factors including nursery rearing, single housing, and veterinary procedures. Much of this research has focused on macaque monkeys; less is known about the extent of and risk factors for abnormal behavior in baboons. Because abnormal behavior can be indicative of poor welfare, either past or present, the purpose of this study was to survey the presence of abnormal behavior in captive baboons and to identify potential risk factors for these behaviors with an aim of prevention. Subjects were 144 baboons (119 females, 25 males) aged 3–29 (median = 9.18) years temporarily singly housed for research or clinical reasons. A 15-minute focal observation was conducted on each subject using the Noldus Observer® program. Abnormal behavior was observed in 26% of the subjects, with motor stereotypy (e.g., pace, rock, swing) being the most common. Motor stereotypy was negatively associated with age when first singly housed (p < 0.005) while self-directed behavior (e.g., hair pull, self-bite) was positively associated with the lifetime number of days singly housed (p < 0.05) and the average number of blood draws per year (p < 0.05). In addition, abnormal appetitive behavior was associated with being male (p < 0.05). Although the baboons in this study exhibited relatively low levels of abnormal behavior, the risk factors for these behaviors (e.g., social restriction, routine veterinary procedures, and sex) appear to remain consistent across primate species.

Keywords: baboon, stereotypy, rearing, housing

Introduction

Abnormal behavior has been observed in a wide variety of primate species housed in captive environments such as zoos and laboratories [Capitanio, 1986; Marriner and Drickamer, 1994]. Behaviors can be considered abnormal if they are qualitatively different (i.e., occur in captivity but not typically in the natural setting) or quantitatively different (i.e., occur significantly more or significantly less than what is observed in the natural setting; Erwin and Deni, 1979). Such behaviors are often stereotypic, in that they are repetitive, frequently idiosyncratic, actions that do not serve any obvious function [Mason, 1991a]. Examples of abnormal behaviors can include motor stereotypies (e.g., pacing, rocking), self-directed behaviors (e.g., hair-pulling, eye-poking), abnormal appetitive behavior (e.g., regurgitation/reingestion, coprophagy), or potentially self-injurious behavior (e.g., self-biting, head-banging; Bayne and Novak, 1998). Abnormal behavior is not an uncommon occurrence; as many as 89–100% of singly housed macaque monkeys have been reported to exhibit some form of abnormal behavior [Bayne et al., 1992; Camus et al., 2013; Lutz et al., 2003], and over 25% of singly and/or indoor-housed rhesus macaques were reported to exhibit motor stereotypy [Lutz et al., 2003; Vandeleest et al., 2011]. These behaviors, especially if they are excessive or result in injury, can negatively impact the animal’s wellbeing as well as the research in which the animal is involved [Novak et al., 2012]. Although abnormal behavior may not always cause an animal harm, it can be an indicator of suboptimal environments, either past or present [Mason, 1991b] and should be further investigated with an aim of improved animal welfare.

Once acquired, abnormal behavior can be very resistant to treatment [Novak et al., 2012]. Although a wide variety of interventions such as additional cage toys, foraging devices, grooming devices, and increased cage space have resulted in reduced abnormal behavior in some animals [Bayne et al., 1991; Bayne et al., 1992; Draper and Bernstein, 1963; Kessel and Brent, 1998], these same manipulations had mixed results or little impact on others [Kaufman et al., 2004; Line et al., 1990; Novak et al., 1998; Paulk et al., 1977; Rommeck et al., 2009a]. Social housing tends to be more effective at reducing abnormal behavior [Bourgeois and Brent, 2005; Kessel and Brent, 2001; Schapiro et al., 1996; Gilbert and Baker, 2011]; however, as with inanimate enrichment, social housing may reduce, but not necessarily eliminate, abnormal behavior [Bourgeois and Brent, 2005; Crockett and Gough, 2002].

Because interventions are typically not successful in eliminating abnormal behavior once it has become a part of the animal’s behavioral repertoire, it is important to identify environmental risk factors with a goal of prevention. Upon identifying relevant risk factors, behavioral management can be appropriately modified, with a focus on the elimination of the initial causes of abnormal behavior. Changing or improving environmental conditions known to be risk factors before the animal first exhibits abnormal behavior may be the most effective strategy for reducing behavioral problems in captive primate populations. However, in order to accomplish such husbandry improvements, the environmental impact on behavior, both early and throughout the animal’s life, needs to be better understood.

Early research by Harlow and Harlow [1962] demonstrated that one main predictor of abnormal behavior in nonhuman primates was an impoverished rearing environment; those reared in partial or total isolation exhibited behavioral abnormalities including pacing, self-clasping, self-biting, and other forms of self-injurious behavior. These findings are supported as more recent studies further demonstrate the impact of rearing history on behavior. Nursery rearing, as well as specific types of nursery rearing (e.g., surrogate-peer-rearing), were shown to be significant predictors for self-biting and “floating limb” in macaque monkeys [Bellanca and Crockett, 2002; Lutz et al., 2007; Rommeck et al., 2009b], and single housing at an early age was associated with abnormal behaviors such as motor stereotypies, self-grasping, self-biting, and self-injury [Lutz et al., 2003]. In addition, monkeys reared indoors were significantly more likely to exhibit motor stereotypies and self-injurious behavior than were those reared in outdoor enclosures [Gottlieb et al., 2013; Rommeck et al., 2009a].

Experiences occurring later in life can also have a negative impact on behavior. In macaque monkeys, single housing for a greater proportion of the animal’s life or for an extended period of time were shown to be significant predictors of abnormal behaviors such as motor stereotypy, eye-poking, hair-pulling, self-biting, and self-injurious behavior [Gottlieb et al., 2013; Lutz et al., 2003; Vandeleest et al., 2011]. In addition, the proportion of the first four years of life in single housing explained approximately 17.3% of the variance in abnormal behavior [Bellanca and Crockett, 2002] and the proportion of life lived indoors was a significant predictor of motor stereotypies [Vandeleest et al., 2011]. The number of sedated blood draws or sedation events performed on the animal was also a significant predictor of motor stereotypies, eye-poking, and self-injurious behavior [Lutz et al., 2003; Vandeleest et al., 2011]. Relocation resulted in an increase in self-biting in monkeys with a history of self-injury [Davenport et al., 2008] and the number of relocations to a different cage showed a significant positive relationship to motor stereotypy and self-injurious behavior [Gottlieb et al., 2013; Rommeck et al., 2009a]. However, this association has not been demonstrated in all subjects [Davenport et al., 2008] or in all studies [Lutz et al., 2003].

Intrinsic factors not affected by the environment can also have an impact on behavioral outcomes. For example, an animal’s sex can play a role in the display of abnormal behavior, and when there was a sex difference, males have typically exhibited more abnormal behavior than females [Bellanca and Crockett, 2002; Gottlieb et al. 2013; Lutz et al., 2003; Novak et al., 2002; Rommeck et al., 2009a; Vandeleest et al., 2011]. Similarly, there are species differences in the display of abnormal behavior. For example, there was no difference between observed and expected numbers (based on percentage in the population) of Macaca fascicularis exhibiting excessive abnormal behavior. However, Macaca nemestrina males exhibited more, and females less, abnormal behavior than expected [Novak et al., 2002], and rhesus macaque “isolates” exhibited abnormal behavior to a greater extent than did pigtail macaque isolates [Sackett et al., 1976]. Finally, age can also play a role in behaviors exhibited. Self-sucking and motor stereotypies tended to decrease with age [Cross and Harlow, 1965; Gottlieb et al., 2013], and younger animals tended to display more active types of abnormal behavior while older animals displayed more self-directed behaviors [Lutz et al., 2003].

Although much has been reported on the extent of, and risk factors for, abnormal behavior in the macaque population [Bellanca and Crockett, 2002; Gottlieb et al., 2013; Lutz et al., 2003; Rommeck et al., 2009a; Vandeleest et al., 2011], less is known about abnormal behavior in the captive baboon population. In 1997, Brent and Hughes reported abnormal behavior such as hair pulling, regurgitation, and pacing in group-housed baboons along with risk factors such as nursery rearing and single housing for these behaviors. However, similar studies in more restrictive environments such as single housing have not been conducted. The purpose of this study was to further document abnormal behavior in captive baboons and to identify potential risk factors for aberrant behaviors in this population.

Methods

Subjects

The subjects were 144 baboons (Papio hamadryas spp.), 25 males and 119 females, ranging in age from 3 to 29 years (median = 9.18) and housed at the Southwest National Primate Research Center in San Antonio, TX. Although the baboons are normally housed outdoors in social groups of approximately 10 individuals, at the time of observation, the subjects had been temporarily singly housed a median of 9 days (Table 1) for either clinical or research reasons. They were maintained in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals [Institute for Laboratory Research, 2011] and were housed in cages ranging from 8 to 15 ft2 depending on the size of the animal, with visual and auditory access to conspecifics. They were all fed a nutritionally balanced diet supplemented with additional fresh produce and food treats, and were provided with chew toys, balls, and other forms of environmental enrichment. The primate facility is accredited by the Association for the Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International, and the behavioral data collection was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. This research adhered to the legal requirements governing research with nonhuman primates in the United States, and to the American Society of Primatologists’ Principles for the Ethical Treatment of Nonhuman Primates.

Table 1.

Quantitative Variables for Subjects

| Variable | Minimum | 1st Quartile | Median | Mean | 3rd Quartile | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 3.14 | 6.96 | 9.18 | 11.73 | 15.74 | 29.34 |

| Average number of blood draws per year | 0.18 | 0.66 | 1.22 | 1.31 | 1.71 | 10.35 |

| Lifetime days singly housed | 8 | 155 | 268.5 | 326.8 | 429.75 | 1415 |

| Age (years) when first singly housed | 0.003 | 0.81 | 1.69 | 2.67 | 4.10 | 10.36 |

| Number of moves to and from single-housing | 1 | 11.75 | 19 | 22.48 | 31 | 85 |

| Consecutive number of days singly housed prior to observation | 0 | 4 | 9 | 24.85 | 28.25 | 184 |

| Number of baboons in room at time of observation | 1 | 4 | 7 | 7.35 | 9 | 22 |

Procedures

Data were collected from September 2007 to August, 2010. A 15-minute focal observation was conducted on each subject using the Noldus Observer® program. The observer was seated approximately 1–1.5 meters from the subject, depending on the arrangement of the room. The observers were not familiar to the subjects and started data collection within minutes of entering the room. Although both normal and abnormal behaviors were recorded, the focus of this study was on abnormal behavior. The abnormal behaviors recorded are listed in Table 2. Two observers collected the data, and they had an inter-observer reliability score of 94% for duration and 92% for frequency. Due to the brief observation period, the data were transformed into one/zero categories for analyses.

Table 2.

Behavioral Categories Recorded

| Behavior | Definition |

|---|---|

| Motor Stereotypy | |

| head toss | Repeated circular movement of the head at the neck, can be performed rapidly or slowly |

| pace | Repeated walking in the same pattern (e.g., back and forth) for at least 3 revolutions |

| rock | Repeated back and forth or side to side movement of the body, occurring at least 3 times |

| swing | Repetitive back-and-forth movement when hanging from the cage side or ceiling |

| Self-directed Behavior | |

| eye poke | placement of fingers or toes into, or right next to, the eye for an extended period of time; often appears as if the animal is “saluting” |

| hair pull | Pulling own hair from body |

| self-bite | Mouth-to-self contact where teeth contact the skin |

| Abnormal Appetitive | |

| abnormal mouth movements | Repeated movement of mouth, lips, or tongue, not associated with eating or manipulating an object in the mouth. |

| coprophagy | Ingesting or manipulating feces in the mouth |

| hair-eat | Chewing or ingestion of hair |

| regurgitate | The backward flow of already swallowed food |

| wiggle digits | Repeated movement of fingers or toes usually at, in, or around the mouth, often associated with regurgitation. |

| Other abnormal | |

| idiosyncratic abnormal behaviors not included in the above list | |

Data Analyses

Because abnormal behavior was relatively infrequent in this population, the analyses were conducted on the categories of behavior (motor stereotypy, self-directed behavior, abnormal appetitive, and other abnormal; Table 1) rather than on individual behaviors. There was no behavioral difference between baboons housed for clinical or research reasons (motor stereotypy: χ2(1) = 1.013, p > 0.30; self-directed: χ2(1) = 0.344, p > 0.50; abnormal appetitive: χ2(1) = 0.118, p > 0.70; other abnormal χ2(1) = 0.558, p > 0.45). Therefore, the two groups (clinical and research) were combined for data analyses.

Even with the grouping of behaviors into categories, overfitting of the data is a concern since it is desirable to have no more than n/10 predictor variables if they are continuous and min(n1, n2) if the variable is dichotomous (such as sex) [Harrell 2010]. In the case of these data n is 144, n1 = 25, and n2 = 119. Since inclusion of sex as a predictor variable allows overfitting to occur with more than two predictor variables, the logistic regressions were performed with and without sex as a covariate.

A logistic regression with the logit link function was used to predict the presence or absence of the various behaviors based on predictor variables made up from a subset of covariates listed in Table 1. The resulting models were used to calculate the Somers’ Dxy rank correlation between predicted probabilities and observed responses. When Dxy = 0, the model is making random predictions and when Dxy = 1, the model is making perfectly accurate predictions.[Harrell, 2010].

Though model selection may use stepwise methods, a single model was chosen to fit each behavior based on a selection of predictor variables (covariates) that have been associated with abnormal behaviors in prior studies and that can in some cases be utilized in the management of captive nonhuman primates. In addition, age related collinearity has been removed where possible as described in the next paragraph. Not using stepwise method and removal of collinearity prevents unwanted bias in the standard errors, p-values, and coefficient estimates (Harrell, 2010).

A subset of the covariates described in Table 1 was selected to use in the analyses of logistic models of each of the four categories of behaviors. Age was correlated with lifetime days singly housed, consecutive number of days singly housed immediately prior to observation, and sex, and was therefore removed as a covariate in the logistic analyses. The need to remove animal age from the covariates also explains the use of blood draws per year instead of the total number of blood draws as a covariate. The complete model included one of the behavior categories as the categorical dependent variable and predictor variables made up of (1) age when first singly housed, (2) average number of blood draws per year, (3) consecutive number of days singly housed prior to observation, (4) lifetime days singly housed, (5) number of animals within the bay at the time of observation, and (6) number of moves to and from single-housing. This complete model was run for each behavior with and without sex as a categorical predictor variable. There were no animals with missing data for any of the covariates.

Statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.02 [R Core Team, 2013] within the RStudio development environment RStudio, 2012].

Results

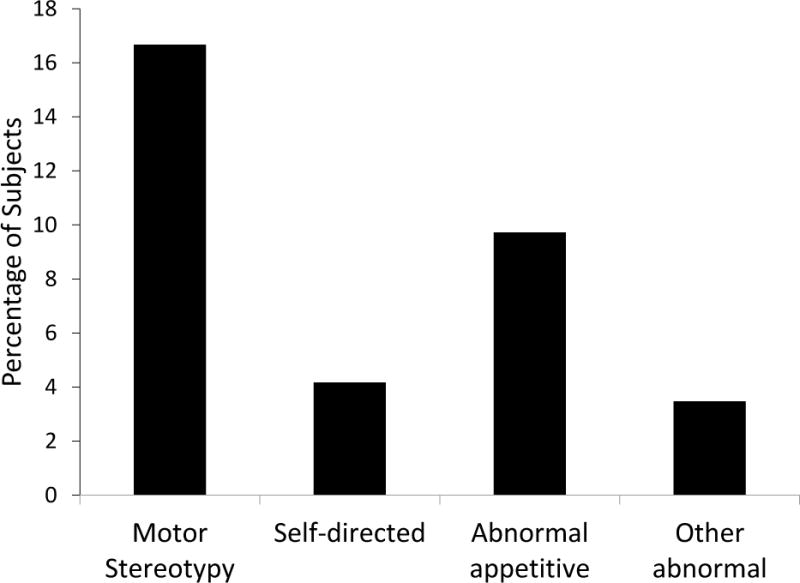

Thirty-seven (26%) of the subjects exhibited at least one abnormal behavior during the 15-minute observation. When lumped into categories, the most common behavioral category observed was motor stereotypy (Figure 1). Presence or absence of sex as a covariate did not change the regression results except in the case of abnormal appetitive behavior where sex has a significant effect. Abnormal appetitive behavior is associated with male baboons (p < 0.05; Table 3). The Somers’ Dxy rank correlation is 0.44. Motor stereotypy was associated with a younger age when first singly housed (p < 0.005; Table 3). The Somers’ Dxy rank correlation is 0.56. Self-directed behavior was associated with higher rates of blood draws (p < 0.05, Table 3) and more lifetime days singly housed (p < 0.05; Table 3). The Somers’ Dxy rank correlation is 0.82. The large standard errors relative to the coefficient estimate sizes precluded the use of these estimates for meaningful interpretation of the magnitude of these effects and thus we have focused on the direction of the effects. There was no significant effect found for the “other abnormal” category of behaviors.

Figure 1.

The extent of abnormal behavior in the study population.

Table 3.

Significant effects of logistic models

| Behavior | Variables | estimate | std. error | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motor Stereotypy | ||||

| – | Age when first singly housed | −0.55 | 0.19 | 0.003 |

| Self-Directed Stereotypy | ||||

| – | Number of blood draws per year | 1.25 | 0.61 | 0.04 |

| – | Lifetime days singly housed | 0.004 | 0.002 | 0.04 |

| Abnormal Appetitive Behavior | ||||

| – | Sex (male) | 1.74 | 0.73 | 0.02 |

Discussion

The aim of this study was to expand our understanding of abnormal behavior in captive nonhuman primates by further assessing aberrant behavior in baboons. The objective was to determine the extent of, and risk factors for, abnormal behavior in baboons, and whether the risk factors in baboons are consistent with those reported in other species of nonhuman primates. Twenty-six percent of the baboons in the present study exhibited some form of abnormal behavior. Although this number is lower than what has been reported in rhesus monkeys, there are study and experiential differences that make a direct comparison difficult. For example, the rhesus monkeys in the Bayne et al. (1992) and the Lutz et al. (unpublished data, 2003) studies had been singly housed at least a year prior to observation, while the baboons in the present study were singly housed for less than a month on average, but were otherwise socially housed outdoors. In addition, there were study differences in length of observation periods and methods of data collection between the present study and those of macaque monkeys [Bayne et al., 1992; Camus et al., 2013; Lutz et al., 2003; Vandeleest et al., 2011]. However, in spite of these study differences, the patterns of behavior exhibited were similar across species. As reported in rhesus [Lutz et al., 2003; Vandeleest et al., 2011] and pigtailed [Bellanca and Crockett, 2002] macaques, as well as in prosimians [Tarou et al., 2005], motor stereotypies (e.g., pace, rock, swing) were more common than other types of abnormal behavior. This contrasts with Brent and Hughes (1997) who report higher levels of self-directed behaviors in baboons. However, the baboons in the Brent and Hughes (1997) study were group-housed in larger enclosures at the time of data collection. Because relative cage size can impact pacing in captive animals [Draper and Bernstein, 1963; Paulk et al., 1977], the differences in types of behaviors displayed may be due to differences in housing condition.

In the present study, a sex difference was observed in abnormal appetitive behavior; males were more likely to exhibit this behavior than were females. This male-biased result is consistent with a number of studies reporting that when there is a sex difference, being male is a significant risk factor for abnormal behavior [Bayne et al., 1995; Brent and Hughes, 1997; Gottlieb et al., 2013; Lutz et al., 2003; Vandeleest et al., 2011]. However, the reason for a significant sex difference remains unclear and should be further investigated.

Age when first singly housed was significantly associated with abnormal behavior; the younger the animal was when first singly housed, the more likely it was to exhibit motor stereotypies. Because age when first singly housed is associated with nursery rearing (i.e., infants that were nursery-reared were classified as singly housed), this result is similar to that obtained by Brent and Hughes (1997) where nursery-reared baboons were also more likely to exhibit motor stereotypies. Previous studies have demonstrated the impact of nursery rearing on other abnormal behaviors such as digit-sucking [Lutz et al., 2003], motor stereotypies [Gottlieb et al., 2013], and self-biting [Bellanca and Crockett, 2002; Gottlieb et al., 2013; Lutz et al., 2007] in macaque monkeys. Behaviors such as floating limb and self-biting were observed to occur as early as 32 days of age in nursery-reared rhesus monkeys [Rommeck et al., 2009b]. In addition, hand-reared primates housed in a zoo environment were significantly more likely to display stereotyped behaviors than were their mother-reared counterparts [Marriner and Drickamer, 1994]. These results all point to the impact of rearing history on later behavioral development and the benefits of mother-rearing.

Duration of single housing also played a role in the display of abnormal behavior. The longer a baboon was singly housed during its lifetime, the more likely it was to exhibit self-directed abnormal behavior. This result is similar to that found in group-housed baboons [Brent and Hughes, 1997] in which baboons that were singly housed for a longer period of time during their lives were more likely to exhibit abnormal behavior such as motor stereotypy. Single housing has often been reported to be a risk factor for abnormal behaviors such as motor stereotypies, self-directed behavior, and self-injurious behavior in rhesus macaques [Bayne et al., 1992; Gottlieb et al., 2013; Lutz et al., 2003; Vandeleest et al., 2011]. In contrast, social housing has consistently been shown to be beneficial to captive nonhuman primates. It enhances a more normal behavioral repertoire [Bayne et al., 1992] and helps to reduce abnormal behavior [Kessel and Brent, 2001].

The impact of routine husbandry events such as relocations on abnormal behavior was mixed. The present study reported no relationship between relocations and abnormal behavior. This result is consistent with previous work in rhesus monkeys [Lutz et al., 2003]. However, other studies reported that cage relocations were associated with motor stereotypies and self-injurious behavior in rhesus monkeys [Davenport et al., 2008; Gottlieb et al., 2013; Rommeck et al. 2009a]. Further research needs to be conducted to better determine the true impact of relocations on nonhuman primates. Blood draws, either for clinical or research purposes, are another routine event for captive nonhuman primates, and they are typically performed on a sedated animal. In the present study, self-directed behavior was positively associated with the average annual number of sedated blood draws the animal experienced. This result is consistent with previous studies which found that an increased number of sedated blood draws was associated with behaviors such as pacing, eye-poking, and self-injury [Lutz et al., 2003], and monkeys with self-injurious behavior (SIB) experienced more medical procedures and more blood sampling in a 5-year period than monkeys without SIB [Novak, 2003]. Vandeleest et al. (2011) assessed anesthesia events and unsedated blood draws separately and found that the anesthesia, and not the blood draw, was a risk factor for motor stereotypy. Because the blood draws in the present study were sedated events, they could not be assessed independently from sedation. However, the results in Vandeleest et al. (2011) suggest that the two events may have a differential impact on behavior.

Correctly identifying variables that are risk factors for abnormal behavior is an important step in improving the care of captive nonhuman primates. Because environmental enrichment can reduce, but not typically eliminate, abnormal behavior, the best strategy is to understand the risk factors for these behaviors with an aim of prevention. Our results indicate that although baboons may exhibit relatively low levels of abnormal behavior, risk factors for these behaviors are similar to those identified in other species. Single housing, either at an early age or for an extended period of time, is consistently shown to have a negative impact on an animal’s later behavior. In addition, routine procedures such as sedations or blood draws have also been shown to have a negative impact on behavior, while other routine procedures, such as relocations, may not. This information can help colony managers understand how their procedures impact the behavior of captive primates and to create a better environment for the animals under their care.

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by Grant # R24OD01180-15 to Melinda Novak at the University of Massachusetts and P51OD011133 to Texas Biomedical Research Institute (SNPRC). We would like to thank K.A. Linsenbardt for assistance with data collection.

References

- Bayne K, Dexter S, Suomi S. A preliminary survey of the incidence of abnormal behavior in rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) relative to housing condition. Lab Animal. 1992;21:38–46. [Google Scholar]

- Bayne K, Haines M, Dexter S, Woodman D, Evans C. Nonhuman primate wounding prevalence: a retrospective analysis. Lab Animal. 1995;24:40–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bayne K, Mainzer H, Dexter S, Campbell G, Yamada F, Suomi S. The reduction of abnormal behaviors in individually housed rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) with a foraging/grooming board. American Journal of Primatology. 1991;23:23–35. doi: 10.1002/ajp.1350230104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayne K, Novak M. Behavioral disorders. In: Bennett BT, Abee CR, Henrickson R, editors. Nonhuman Primates in Biomedical Research, Diseases. New York: Academic Press; 1998. pp. 485–500. [Google Scholar]

- Bellanca RU, Crockett CM. Factors predicting increased incidence of abnormal behavior in male pigtailed macaques. American Journal of Primatology. 2002;58:57–69. doi: 10.1002/ajp.10052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgeois SR, Brent L. Modifying the behaviour of singly caged baboons: evaluating the effectiveness of four enrichment techniques. Animal Welfare. 2005;14:71–81. [Google Scholar]

- Brent L, Hughes A. The occurrence of abnormal behavior in group-housed baboons. American Journal of Primatology. 1997;42:96–97. [Google Scholar]

- Camus SMJ, Blois-Heulin C, Li Q, Hausberger M, Bezard E. Behavioural profiles in captive-bred cynomolgus macaques: towards monkey models of mental disorders? PLOS One. 2013;8:1–14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capitanio JP. Behavioral pathology. In: Mitchell G, Erwin J, Swindler DR, editors. Comparative Primate Biology, vol 2A: Behavior, Conservation, and Ecology. New York: Alan R. Liss, Inc; 1986. pp. 411–454. [Google Scholar]

- Crockett CM, Gough GM. Onset of aggressive toy biting by a laboratory baboon coincides with cessation of self-injurious behavior. American Journal of Primatology (Supplement 1) 2002;57:39. [Google Scholar]

- Cross HA, Harlow HF. Prolonged and progressive effects of partial isolation on the behavior of macaque monkeys. Journal of Experimental Research in Personality. 1965;1:39–49. [Google Scholar]

- Davenport MD, Lutz CK, Tiefenbacher S, Novak MA, Meyer JS. A rhesus monkey model of self-injury: Effects of relocation stress on behavior and neuroendocrine function. Biological Psychiatry. 2008;63:990–996. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draper WA, Bernstein IS. Stereotyped behavior and cage size. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 1963;16:231–234. doi: 10.2466/pms.1963.17.2.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erwin J, Deni R. Strangers in a strange land: abnormal behaviors or abnormal environments? In: Erwin J, Maple TL, Mitchell G, editors. Captivity and Behavior, Primates in Breeding Colonies, Laboratories, and Zoos. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold; 1979. pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert MH, Baker KC. Social buffering in adult male rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta): effects of stressful events in single vs. pair housing. Journal of Medical Primatology. 2011;40:71–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2010.00447.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb DH, Capitanio JP, McCowan B. Risk factors for stereotypic behavior and self-biting in rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta): animal’s history, current environment, and personality. American Journal of Primatology. 2013;75:995–1008. doi: 10.1002/ajp.22161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlow HF, Harlow MK. Social deprivation in monkeys. Scientific American. 1962;207:136–146. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican1162-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell FE. Regression modeling strategies: with applications to linear models, logistic regression, and survival analysis. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2010. pp. 56–61. [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Laboratory Animal Research. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. 8. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman BM, Pouliot AL, Tiefenbacher S, Novak MA. Short and long-term effects of a substantial change in cage size on individually housed, adult male rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 2004;88:319–330. [Google Scholar]

- Kessel AL, Brent L. Cage toys reduce abnormal behavior in individually housed pigtail macaques. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science. 1998;1:227–234. doi: 10.1207/s15327604jaws0103_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessel A, Brent L. The rehabilitation of captive baboons. Journal of Medical Primatology. 2001;30:71–80. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0684.2001.300201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Line SW, Morgan KN, Markowitz H, Strong S. Increased cage size does not alter heart rate or behavior in female rhesus monkeys. American Journal of Primatology. 1990;20:107–113. [Google Scholar]

- Lutz CK, Davis EB, Ruggiero AM, Suomi SJ. Early predictors of self-biting in socially-housed rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) American Journal of Primatology. 2007;69:584–590. doi: 10.1002/ajp.20370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz C, Well A, Novak M. Stereotypic and self-injurious behavior in rhesus macaques: a survey and retrospective analysis of environment and early experience. American Journal of Primatology. 2003;60:1–15. doi: 10.1002/ajp.10075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marriner LM, Drickamer LC. Factors influencing stereotyped behavior of primates in a zoo. Zoo Biology. 1994;13:267–275. [Google Scholar]

- Mason GJ. Stereotypies: a critical review. Animal Behaviour. 1991a;41:1015–1037. [Google Scholar]

- Mason GJ. Stereotypies and suffering. Behavioural Processes. 1991b;25:103–115. doi: 10.1016/0376-6357(91)90013-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak MA. Self-injurious behavior in rhesus monkeys: new insights into its etiology, physiology, and treatment. American Journal of Primatology. 2003;59:3–19. doi: 10.1002/ajp.10063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak MA, Crockett CM, Sackett GP. Self-injurious behavior in captive macaque monkeys. In: Schroeder SR, Oster-Granite ML, Thompson T, editors. Self-Injurious Behavior: Gene-Brain-Behavior Relationships. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Books; 2002. pp. 151–161. [Google Scholar]

- Novak MA, Kelly BJ, Bayne K, Meyer JS. Behavioral disorders of nonhuman primates. In: Abee C, Mansfield K, Tardif S, Morris T, editors. Nonhuman Primates in Biomedical Research Biology and Management. Vol. 1. Waltham, MA: Elsevier; 2012. pp. 177–196. [Google Scholar]

- Novak MA, Kinsey JH, Jorgensen MJ, Hazen TJ. Effects of puzzle feeders on pathological behavior in individually housed rhesus monkeys. American Journal of Primatology. 1998;46:213–227. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2345(1998)46:3<213::AID-AJP3>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulk HH, Dienske H, Ribbens LG. Abnormal behavior in relation to cage size in rhesus monkeys. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1977;86:87–92. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.86.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2013. URL http://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- RStudio. RStudio: Integrated development environment for R (Version 0.98.216) [Computer software] Boston, MA: 2012. Retrieved July 24, 2013. Available from http://www.rstudio.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Rommeck I, Anderson K, Heagerty A, Cameron A, McCowan B. Risk factors and remediation of self-injurious and self-abuse behavior in rhesus macaques. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science. 2009a;12:61–72. doi: 10.1080/10888700802536798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rommeck I, Gottlieb DH, Strand SC, McCowan B. The effects of four nursery rearing strategies on infant behavioral development in rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) Journal of the American Association for Laboratory Animal Science. 2009b;48:395–401. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sackett GP, Holm RA, Ruppenthal GC. Social isolation rearing: species differences in behavior of macaque monkeys. Developmental Psychology. 1976;12:283–288. [Google Scholar]

- Schapiro SJ, Bloomsmith MA, Suarez SA, Porter LM. Effects of social and inanimate enrichment on the behavior of yearling rhesus monkeys. American Journal of Primatology. 1996;40:247–260. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2345(1996)40:3<247::AID-AJP3>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarou LR, Bloomsmith MA, Maple TL. Survey of stereotypic behavior in prosimians. American Journal of Primatology. 2005;65:181–196. doi: 10.1002/ajp.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandeleest JJ, McCowan B, Capitanio JP. Early rearing interacts with temperament and housing to influence the risk for motor stereotypy in rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 2011;132:81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]