Abstract

Electrospun polymer nanofibers have multiple applications in the tissue engineering field despite limited cell penetration within the scaffolds and slow synthesis rates. Airbrushing, a proposed alternative to traditional electrospinning, is a technique capable of synthesizing open structure nanofiber scaffolds at high rates. In this study, three biocompatible polymers—poly-D,L-lactic acid (P-DL-LA), polycaprolactone (PCL), and poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA), were airbrushed to form networks for bone tissue regeneration. All three polymers were loaded with up to 20% (w/w) zirconium-modified amorphous calcium phosphate (Zr-ACP). A simple one-step mix and straightforward material deposition yielded open structure networks with well-distributed Zr-ACP. Cell penetration within the airbrushed scaffolds was found to be more than twice the cell penetration within conventional electrospun networks. The airbrushed polymer network supported cell growth and differentiation. Cells grown on the Zr-ACP in P-DL-LA fibers exhibited improved levels of osteocalcin protein with an increase in the Zr-ACP content by day 16. This airbrushing method promises to be a viable and attractive alternative to currently used electrospinning techniques in the formation of composite 3D nanofiber scaffolds for tissue engineering applications.

Introduction

Biocompatible polymer nanofibers are widely used in vitro and increasingly more often for in vivo biomedical research.1,2 Fibers with submicron and nanoscale diameters are uniquely attractive for tissue regeneration because they resemble extracellular matrix (ECM) collagen fiber morphology. The nanofibers have the ability to mimic the ECM and are known to support cell growth and differentiation. Over the past few years, polymer nanofibers have been examined for a number of bioengineered applications such as wound healing and scaffolds for bone regeneration.3,4

The fibers can be synthesized from a wide range of biocompatible polymers by adjusting material chemistry and degradation rates. Different types of polymer fibers can affect the rate of material degradation, loading and release of biomolecules, and material mechanical properties.5,6 The flexibility in material selection allows for engineering scaffolds that can match specific tissue material properties and regeneration dynamics.7,8

Polymer fibers may be synthesized by micro and submicron size extrusion, melt-blowing, force-spinning, flash-spinning or coaxial spinneret electrospinning. However, basic electrospinning is still the most commonly reported and used technique within the literature.9–12

Electrospun scaffolds provide a quasi-three-dimensional (3D) environment that is mainly dominated by cell interactions in horizontal directions. Closely deposited nanofibers can create dense mats limiting cell in-growth within the scaffold and thereby, providing a limited 3D platform.13 Synthesizing scaffolds where cells penetrate within networks and interact in both horizontal and vertical directions is still challenging and underreported.14–16 Ideally, to better facilitate cell connectivity in all directions, fibrous scaffolds should have an open structure while providing biomimicking tissue morphology on both a micro and submicron scale. Adequate cell-material compatibility can potentially guide and promote cell growth, cell–cell communication, and order within a 3D matrix. A recent publication by Kumar et al. has highlighted the importance of nanofiber morphology on cell response in human bone marrow stromal cells (hBMSCs).17 It is also known that cells in osteocyte networks within lacunar and canalicular cavities are highly aligned and feature extensive cell–cell interconnectivity on a microscale.18 In another study, ECM fiber alignment was shown to impact cell length order at lengths greater than a few hundred microns; in addition, it also indicated that the extent of cell order can correspond to bone type and quality.19 These studies underscore the importance of the material morphology on cell arrangement and interconnectivity within native and 3D scaffolds. Properly engineered 3D fibrous scaffolds can potentially facilitate cell–cell interactions that extend in both horizontal and vertical directions to form native tissue-like formation.

Bulk biocompatible materials are known to sustain cell growth, but their bioactivity can be further enhanced by incorporating controlled-release biomolecules.20 As reported in literature, numerous nanofiber composite materials incorporate calcium (Ca) and phosphate (P) biomolecules. Once placed in an aqueous environment, these biomolecules are released and aid bone tissue regeneration.6,21 Calcium, in various forms, is the main bone component essential for maintaining cell and tissue homeostasis. These ubiquitous ions are present in many cell organelles where they actively mediate energy generation, internal cell communication, cell movement, and even its final fate.22,23 Poorly crystallized apatite forms of calcium phosphate are the principle materials in adult bone and tooth structures.24 However, physiological bone formation is a highly dynamic process. During embryonic, infant, and adolescent development, bone becomes progressively more rigid and crystallized when highly soluble amorphous calcium phosphate (ACP) is converted over time to the stable hydroxyapatite form.25 More importantly, bioavailable Ca and P ions are known to be essential for proper bone formation and healing.26 In vitro studies indicate that ACP composites can support mouse osteoblastic cell growth and differentiation.27–29 In addition, recent studies have shown that poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) microspheres coated with zirconium-modified amorphous calcium phosphate (Zr-ACP) promoted preosteoblast cell attachment and supported cell differentiation.28,30

Although electrospinning provides fine control over nanofiber synthesis, there are some limitations to applications in tissue engineering such as the inability to deposit fibers without an electric field, slow deposition rates, complex synthesis setups, and poor cell penetration within a fibrous network.13,31 As shown in this and our earlier studies, nanofiber airbrushing provides a solution to many of these limitations.32 Certain bulk material properties and scaffold morphology, including the Young's modulus, network pore size and porosity were reported to be different between electrospun and airbrushed scaffolds and potentially advantageous for tissue regeneration applications.32 Therefore, the objective of this study was to (a) evaluate the use of an airbrush device as a method of synthesizing Zr-ACP composite nanofiber scaffolds from various polymers; (b) evaluate the extent of cell penetration within more open structure of the nanofiber networks; (c) investigate the ability of a composite fiber to release Zr-ACP biomolecules; and (d) examine the effect of Zr-ACP on hBMSC growth and differentiation.

Materials and Methods

Polymer composite nanofiber fabrication

Three biocompatible polymers were dissolved in organic solvents: 4% (w/w) polycaprolactone (PCL, MW=70–90,000 Da; Sigma-Aldrich) in chloroform, 8% (w/w) poly-D,L-lactic acid (P-DL-LA, MW=115,000 Da; SurModics Pharmaceuticals) in acetone, and 10% (w/w) poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA, MW=500,000 Da; Sigma) in acetone. Master Airbrush (G222-SET), a commercially available airbrush, was used to produce polymer fibers from these polymer solutions. The airbrush was fitted with a 0.3-mm-diameter nozzle, and using pressurized air (30–40 psi), the fibers were deposited 20 cm from the target. Nanofibers were deposited onto a target of tissue culture polystyrene (TCPS) discs (d=11.56 mm) for cell culture experiments.

Separately, Zr-ACP powder (synthesis based on a method described by Eanes et al., and further modified by Zhang et al.) was dispersed in the three polymer solutions listed above at either 5% or 20% (w/w).33,34 The composite polymer nanofibers were produced using a two-step process: (a) mixing Zr-ACP powder with solvent and polymer and (b) airbrushing the composite onto TCPS discs.

Electrospun scaffolds, for the cell penetration study, were fabricated using PCL 10% (w/w) in a chloroform/methanol solution (75:25 ratio) at a rate of 2 mL/h, using a 20-gauge needle and placed 15 cm away from a TCPS target at a charge of 16.5 kV.

Polymer composite nanofiber characterization

The Zr-ACP content within the composite fibers was confirmed by gravimetric measurement of the fibers using thermal gravimetric analysis (model Q500; TA Instruments). Samples were heated at 10°C/min to reach a final temperature of 800°C.

Physical features of all polymer mats were characterized using scanning electron microscopy (SEM, S-4700-II FE-SEM; Hitachi). Three individual scaffolds for each polymer type were imaged using the SEM to assess the average fiber diameter and scaffold thickness. The polymer fiber diameter was calculated by averaging the diameter of 15 fibers on each image. Energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) and AZtecEnergy software were used to detect Ca and P ions in P-DL-L scaffolds.

The calcium and phosphate ion release data were obtained by suspending 100 mg of 0%, 5%, and 20% (w/w) Zr-ACP in P-DL-LA composite scaffolds in individual holders. Each holder was suspended in a 50 mL buffered saline solution (pH=7.4) and continuously stirred at room temperature. Aliquots were collected (1.0 mL) at 0-, 1-, and 4-week intervals and replaced with 1.0 mL of fresh buffer solution. The total cumulative calcium and phosphate ion concentrations were measured with inductively coupled plasma–atomic emission spectroscopy (Prodigy; Teledyne Leeman Labs) using known standards and calibration curves. Data obtained were analyzed with Salsa software for selected Ca line=393.366 nm and P line=213.618 nm wavelengths. The average total weight loss for each type of polymer scaffold (n=4) was calculated by removing the scaffold specimens from the saline solution at different intervals (0, 2, 4, and 6 weeks). Specimens were dried for 24 h under house vacuum, reweighed, and returned to the saline solution.

In vitro cell culturing

Before the cell culture experiments, the scaffold/TCPS discs were sterilized by briefly rinsing twice in 70% ethanol (v/v). The discs were dried and mounted in 48-well polystyrene plates (Corning). Primary hBMSCs [Tulane Center for Gene Therapy, P(4)] were seeded on plates with 10,000 cells per well (n=3) and cultured using 5% (v/v) CO2 at 37°C in the α-minimum essential medium (Invitrogen) containing 16.5% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals) and 4 mmol l-glutamine.17 The cells were cultured up to 50 days without using osteogenic supplements.

Cell fluorescent staining

Cells were stained by fixing cell cultures in 3.7% (v/v) formaldehyde (in phosphate-buffer solution [PBS]) for 15 min, rinsed in PBS, treated for 5 min with 0.2% (v/v) Triton X-100 in PBS and then rinsed twice in PBS. The cells, on scaffolds (n=2), were fluorescently stained with nucleic stain (Hoechst 33342; Invitrogen) and F-actin stain (AlexaFluor 546-phalloidin; Invitrogen) for 30 min, rinsed in PBS, and air-dried. Images were taken at day 16 for better cell assessment. At later time points (day 50), the cells were found to create multilayers and dense ECM that obstructed cell imaging and assessment.

Cell penetration within scaffolds

PCL airbrushed and electrospun scaffolds were used as a model to assess hBMSC morphology and penetration rates within scaffolds. In our previous publication, we reported that the measured relative pore size and porosity were higher in airbrushed scaffolds.32 The cells were fixed, as described above, and fluorescently stained to image the cell nucleus and determine cell penetration rates (Hoechst 33342) at day 1. Four PCL specimens of both airbrushed and electrospun scaffolds were scanned through confocal microscopy (TCS SP5 broadband, 10×/0.3 NA objective; Leica). Z-stack images (0.7 μm step size, 1024×512 pixel image resolution, pinhole size=1 Airy Unit, line averaging of n=3) were examined with ImageJ software (NIH) to calculate the average cell penetration rate.

Cell DNA content

A Picogreen® DNA assay kit (Invitrogen) was utilized to quantify cellular DNA on experimental scaffolds. Specimens were rinsed with PBS and then treated with a lysis buffer (PBS with 0.175 U/mL papain and 14.5 mmol l-cysteine) for 17 h at 60°C to produce cellular lysate. The lysate was then transferred to a 96-well plate (0.2 mL/well), mixed with the Picogreen reagent (0.2 mL/well), and measured using a plate reader to assess DNA concentrations (excitation 485 nm, emission 538 nm). Cell–scaffold constructs were collected at day 1, 16, and 50 to determine the total amount of cell DNA for each scaffold.

Osteocalcin protein content

Intact osteocalcin (OC) protein levels were assessed using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA, BT-460; Biomedical Technologies, Inc.). Collected scaffolds (n=3, for day 16 and 50) were first rinsed in PBS, then treated with 10% (v/v) acetic acid for 1 h at 37°C, lyophilized, and then finally frozen until measurement. One hundred microliters of the sample buffer (from ELISA kit) was added to thaw out samples and resuspend the protein. The reconstituted samples were then processed following the manufacturer's protocol. Collected data were fit to a standard curve to determine the final OC concentration.

Data analysis and statistics

The one-way ANOVA test with Tukey extension was used to analyze data for each polymer type (Figs. 2–4, 6 and 7). The statistical analysis was applied to data that had a normal distribution profile. The significance level was set at p=0.05. Simple linear regression analysis was conducted on ion release and weight loss data (between 0 and 4 weeks) to calculate the correlation coefficient R2 (Fig. 7).

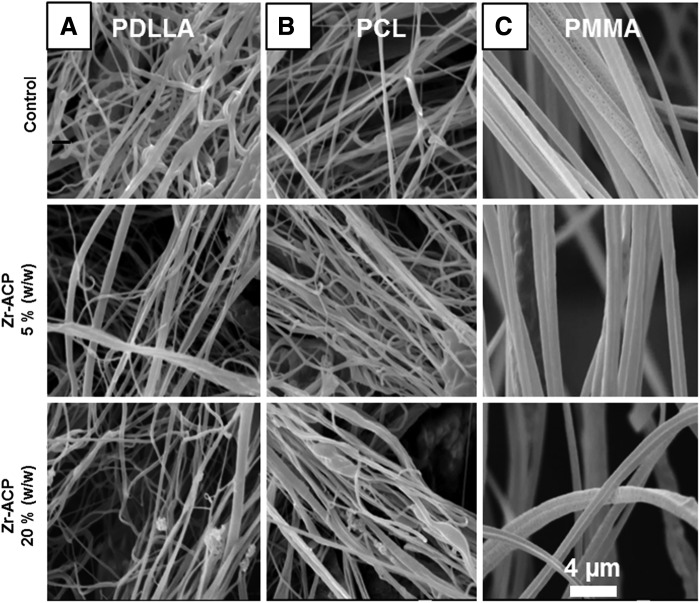

FIG. 2.

Airbrushed polymer Zr-ACP nanofibers. The fibers were loaded with 0%, 5%, and 20% (w/w) Zr-ACP powder. Fiber morphology and diameter were not visibly affected by the Zr-ACP content for either poly-D,L-lactic acid (P-DL-LA) (A), polycaprolactone (B) or poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) (C) polymer. A larger fiber diameter, due to the polymer type, can be seen in PMMA fibers (C).

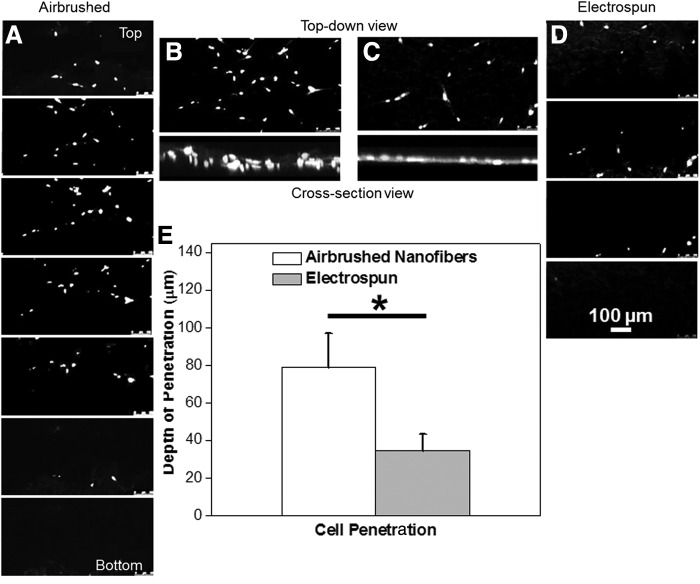

FIG. 3.

Cell penetration within electrospun and airbrushed scaffolds. Nucleus stained human bone marrow stromal cells (hBMSCs) penetrated deeper within the airbrushed networks (image taken at day 1), as seen in the stack of confocal images (A–D). Projected and cross-section view of the scaffold suggests a greater cell distribution in the z vertical direction on the airbrushed mats (B, C). Average cell penetration depth was estimated ∼78 μm on airbrushed and ∼34 μm for electrospun networks (E). “*” Significant difference, p<0.05. Factors compared: cell penetration within the electrospun and airbrushed scaffolds.

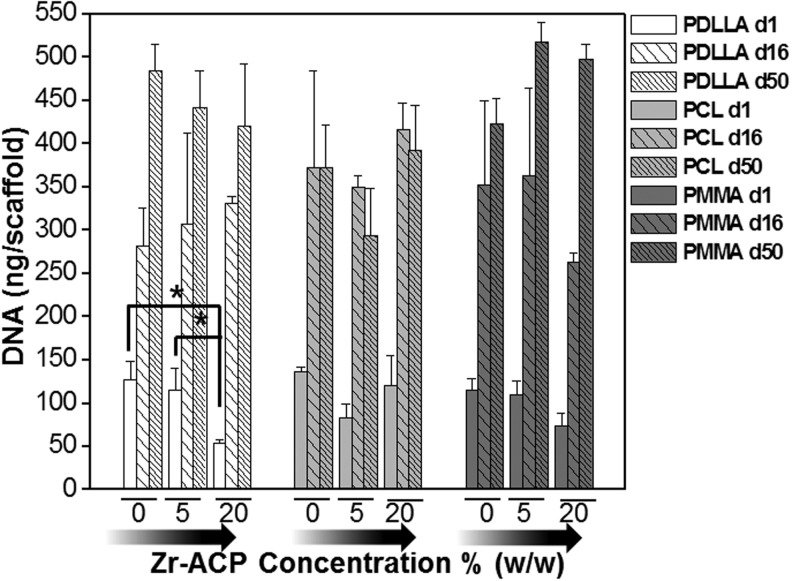

FIG. 4.

Total cell DNA content on composite Zr-ACP nanofiber scaffolds. The cell DNA amount for the same type of polymer scaffold was similar and indifferent to the Zr-ACP content. A significant drop in detected DNA content was observed for cells grown on 20% (w/w) Zr-ACP P-DL-LA fibers at day 1. The DNA level was statistically similar in all other groups for each polymer type by day 16. “*” Significant difference, p<0.05. Factors compared: effect of Zr-ACP content on cell DNA content at day 1, 16, and 50.

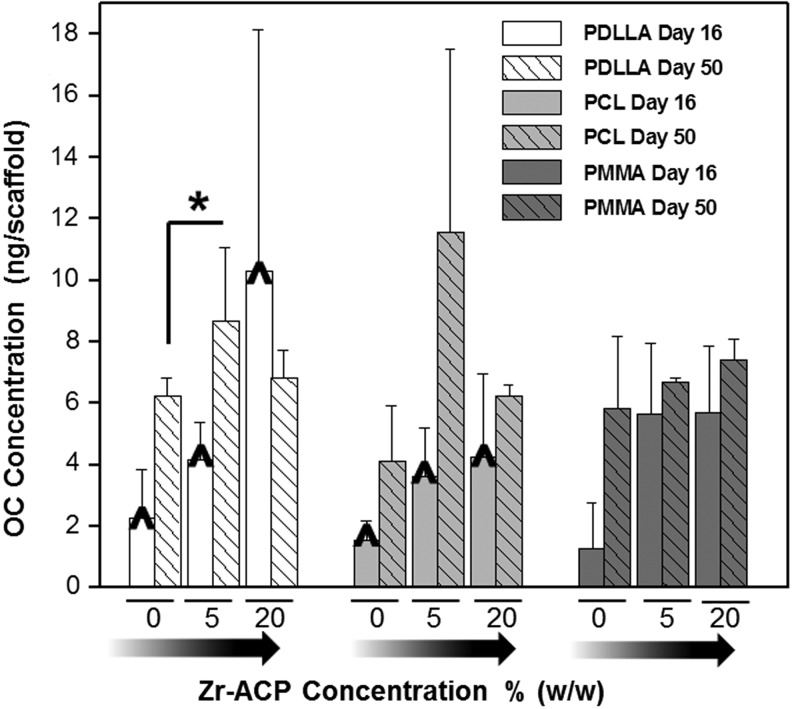

FIG. 6.

Osteocalcin (OC) protein levels in hBMSCs grown on the composite scaffolds at day 16 and 50. Detected OC protein levels were similar in most of the cells grown on the same type of polymer nanofibers regardless of Zr-ACP content. The increase in OC levels (P-DL-LA samples) appeared to correspond with an increase in Zr-ACP concentration and formed a trend, as denoted by “^.” A similar but weaker trend can be seen in cells grown on polycaprolactone (PCL) nanofiber networks. “*” Significant difference, p<0.05. Factors compared: effect of Zr-ACP concentration on OC levels at day 16 and 50.

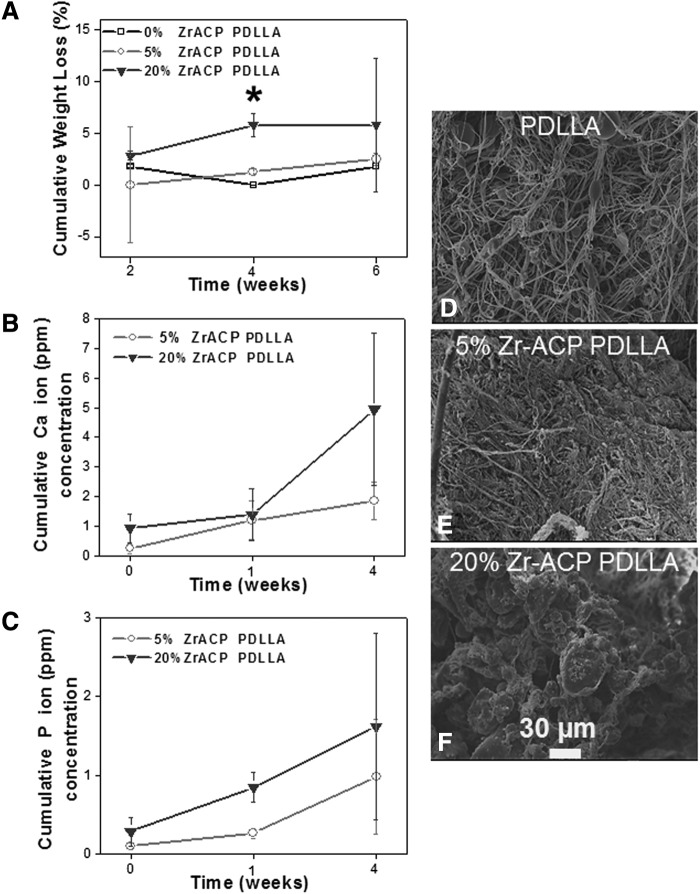

FIG. 7.

Cumulative P-DL-LA scaffold weight loss and calcium (Ca)/phosphate (P) ion release from the composite fibers over time. Highest polymer weight loss was detected in samples with 20% (w/w) Zr-ACP after 4 weeks (A). The increase in weight loss correlated weakly with an increase in Ca/P ion release (B, C). Polymer structural degradation appeared to be the primary driving force for ion release (D–F). Shown micrographs indicated greater morphological changes in fibers with 20% (w/w) Zr-ACP content (F). “*” Significant difference, p<0.05. Factors compared: effect of Zr-ACP concentration on scaffold cumulative weight loss over time.

Results

Airbrushing and characterization of Zr-ACP polymer nanofiber scaffolds

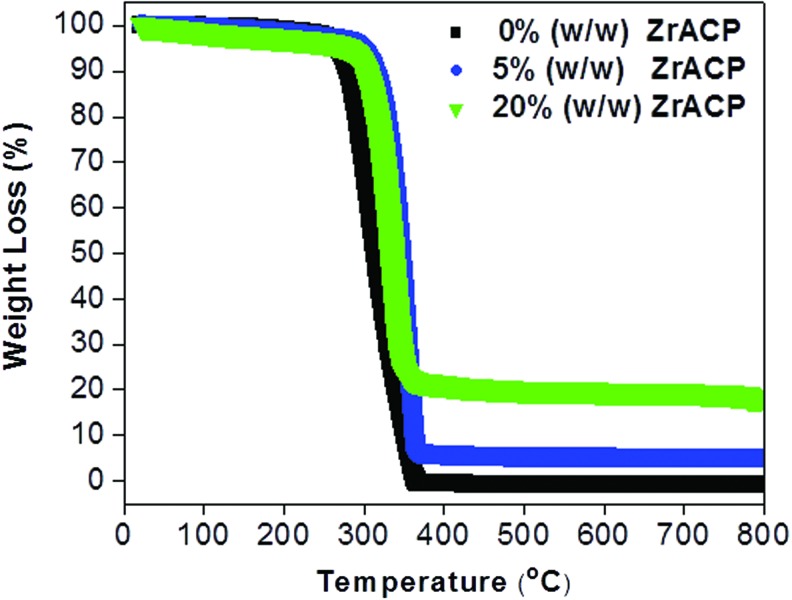

Zr-ACP was successfully incorporated into all three biocompatible polymers (PCL, P-DL-LA, and PMMA) in a one-step process. Submicron and nanofiber scaffolds were easily formed from the experimental polymer compositions using a commercially available airbrush. Our observations and results reported in literature indicated that the type of polymer used had an effect on the final polymer fiber diameter.32,35 The largest fiber diameter was measured for PMMA polymer (dave=0.79±0.2 μm), followed by P-DL-LA (dave=0.28±0.05 μm) and PCL (dave=0.21±0.07 μm). All three polymers were able to incorporate up to 20% (w/w) dry Zr-ACP powder (Fig. 1) without visibly effecting fiber diameters (Fig. 2A–C). SEM-EDS provided a more detailed analysis of the P-DL-LA polymer composite and confirmed that incorporated Ca and P ions were well distributed within the fibers (Supplementary Fig. S1A, B; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec). Similar Ca and P ion distributions were observed in PCL and PMMA fibers (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Zirconium-modified amorphous calcium phosphate (Zr-ACP) content in the poly-D,L-lactic acid (P-DL-LA) nanofiber scaffolds. Thermogravimetric analysis verified the ability of the fibers to retain 5% and 20% (w/w) of Zr-CaP in P-DL-LA polymers. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec

Previously, we reported that the measured relative pore size and porosity were higher in airbrushed scaffolds.32 To assess the biorelevance of this new network macromorphology, hBMSCs were seeded on airbrushed and electrospun PCL scaffolds. The depths of cell penetration were greater in the airbrushed polymer PCL networks than in the electrospun scaffolds. The cells penetrated an average of 78.75±18.46 μm within the airbrushed networks, Figure 3A and B (an average scaffold thickness: 176.06±54.60 μm). Cells deposited on electrospun scaffolds (an average scaffold thickness: 46.18±32.50 μm) had an average penetration depth of 34.75±8.77 μm (Fig. 3C, D). Average cell penetration within the deposited airbrushed scaffold was twice as high as in the electrospun mats (Fig. 3E).

hBMSC response to composite scaffolds

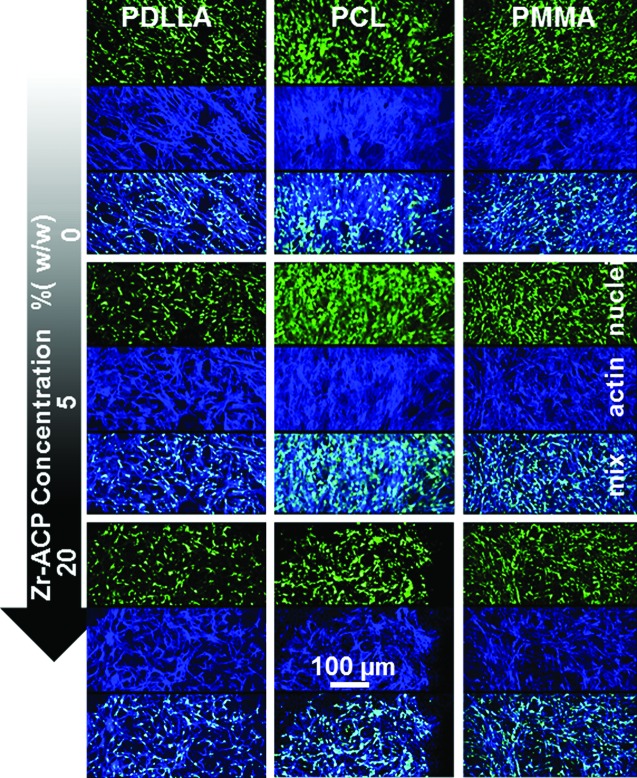

Long-term hBMSC cultures on 0%, 5%, and 20% (w/w) Zr-ACP composite fiber scaffolds showed similar total DNA content patterns, regardless of the biomolecule content for each tested polymer type (Fig. 4), with one exception. At day 1, Zr-ACP 20% (w/w) in P-DL-LA scaffolds had the total cell DNA content decreased drastically; however, by day 16, the DNA amount was statistically similar to all other groups. Changes to cell morphology in response to the tested polymer networks were visually assessed by means of imaging hBMSC nuclei and actin filaments on day 16. Overall, cell spread on polymer fibers and cell distribution appeared to be relatively similar in all imaged samples regardless of the material type and Zr-ACP content (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

hBMSC distribution and microfilament actin spread on the tested polymer scaffolds. Cell distribution (nuclei, green color, top section) and spread (actin, blue color, middle section) on tested polymer nanofibers appeared to be similar in all tested samples by day 16. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec

The impact of polymer composite scaffolds on multipotent hBMSC differentiation was investigated by quantifying OC protein levels in cell–scaffold constructs on day 16 and 50. By day 50, in many cases, no statistical differences were found between OC levels (for specific polymer type), regardless of the Zr-ACP content. Only statistically significant different OC levels were detected in cells grown on 0% and 5% (w/w) Zr-ACP P-DL-LA fibers. However, day 16, specimens exhibited visible signs of a trend for OC levels on P-DL-LA nanofibers with increasing amounts of Zr-ACP (Fig. 6). A similar, yet less prominent, trend on day 16, was also observed in PCL and PMMA composite fiber networks. Comparisons between the OC amounts detected on Zr-ACP P-DL-LA scaffolds [0% and 5% as well as 5% and 20% (w/w)] showed that the results were not statistically significant (p=0.12 and p=0.28). Similar comparison for PCL polymers yielded p=0.11 and p=0.55 and for PMMA polymers, p=0.10 and p=0.64 values, respectively.

In vitro polymer scaffold weight loss and subsequent Ca and P ion release were evaluated to correlate the effect of the composite P-DL-LA fiber degradation on hBMSC responses. Biodegradation results indicated that the P-DL-LA scaffolds alone (0% Zr-ACP) had a low total weight loss (∼2.5%) by week 4. As expected, the composite P-DL-LA with the highest content of Zr-ACP 20% (w/w) had the greatest and statistically significant total weight loss of ∼5% after 4 weeks. Results from the 5% (w/w) Zr-ACP in P-DL-LA composite fibers indicated a small cumulative weight loss (Fig. 7A). Imaged scaffolds revealed that by week 4, the 20% (w/w) Zr-ACP in P-DL-LA composite fibers exhibited an extensive structural decomposition as compared with the relatively intact 0% and 5% (w/w) Zr-ACP in P-DL-LA networks (Fig. 7D–F). Quantification of Ca and P ion release revealed similar relationships. The highest initial and final Ca and P cumulative ion release was recorded for 20% (w/w) Zr-ACP in P-DL-LA composite fibers (Fig. 7B, C). Linear regression analysis showed a weak correlation between polymer weight loss and Ca (R2=0.34) ion release, but improved P (R2=0.67) ion delivery.

Discussion

Electrospun scaffolds offer a quasi-3D environment, in which cells can only interact with other cells on the same horizontal plane. Data presented in this study indicate that a more porous airbrushed scaffold structure allows for a twice deeper cell penetration than does electrospun scaffolds. The ability of cells to penetrate deeper within the scaffolds supports the possibility of creating multilayered interconnected cellular sheets. Airbrushed matrices have the potential to extend cellular interactions into a third z direction with greater lateral and vertical cell–cell connectivity within nanofiber scaffolds. Few electrospun-based techniques can provide scaffolds with enhanced cell penetration, but many (if not all) require extensive material processing. In some cases, during nanofiber scaffold synthesis, the porogen material must be first mixed in and then washed off to form scaffolds with an open-pore structure. Other methods may require unique solvents or specifically designed fiber collecting devices.4,13,16 On the other hand, airbrushing is a simple, safe, and robust method (composite nanofiber synthesis from various polymers) allowing for more open-pore scaffold structure synthesis.

This research also highlights the straightforward approach to incorporate Ca and P ions within the biocompatible polymers. All the tested polymeric matrices (PCL, P-DL-LA, PMMA) exhibited robust loading capability. This one-step approach appears to be limited by the amount of Zr-ACP added to the polymer-solvent solution to form well-blended polymer–biomolecule composites. It is likely that other polymers and biomolecules can be used to form composite fibers. Proper processing parameters such as well-blended composites, the right solvent (low boiling point), and higher MW polymers appear to be the most important parameters required for successful nanofiber synthesis.

In addition, this study also highlights biocompatibility and potential applicability of airbrushed scaffolds for tissue regeneration. A hBMSC-material response evaluation revealed that cells interacted well with all of the tested scaffolds. Specifically, the hBMSCs were shown over time to have increased total DNA content, well-spread actin, and ability to differentiate. A significant drop in cell number on day 1 was observed in 20% (w/w) Zr-ACP in P-DL-LA samples and was likely caused by either sudden fiber degradation (and subsequent ion release from Zr-ACP) or spontaneous ion diffusion out of the fibers. A polymer fiber high-aspect ratio, P-DL-LA hydrophobicity, and a relatively high biomolecule content [20% (w/w)] could have contributed to both a faster polymer breakdown (hydrolysis) and higher Zr-ACP diffusion rates.36 Consequently, released ions may have affected cell signaling pathways leading to lower initial cellular DNA.22 These cells recovered later in the experiment. No similar cellular response was detected in any other sample type.

Long-term cell differentiation results indicated that Zr-ACP incorporated in the PCL and PMMA fibers had a minimum effect on cell response likely due to slow polymer degradation rates. For example, the cell response to Zr-ACP in PMMA composites appeared to be minimal, since measured OC protein levels did not show Zr-ACP-related trends. However, better results were observed for PCL polymer composites by day 16. Our data indicated a slight increase in OC levels in response to the increase in Zr-ACP contents in PCL polymers. A modestly increasing trend was detected between the Zr-ACP content in P-DL-LA and detected average OC protein concentration by day 16. The results suggest that despite the advantage of fiber nanostructure morphology (high-aspect ratios and surface area), the tested polymers could not effectively release Ca and P ions from the fibers. More in-depth analysis of the most responsive P-DL-LA scaffolds showed that the fibrous scaffolds had a relatively low total weight loss. The highest weight loss was recorded for 20% (w/w) Zr-ACP in P-DL-LA samples. Structural breakdown appeared to be the primary driving force for time-dependent Ca and P ion release. The obtained results indicate that fibers made of either P-DL-LA or PCL polymers may be the best choices for controlling material chemistry, degradation rate, and release of Zr-ACP biomolecules.

This report highlights the advantages of using an airbrushing technique for bone tissue regeneration. Airbrushing allows for easy synthesis of polymer nanofiber composite scaffolds with an open structure and higher cell penetration rates. The airbrushing process proves to be an adaptable technique, enabling 3D scaffold synthesis at high rates without the need for extensive material postprocessing. The technique allows for easy Zr-ACP biomolecule incorporation [up to 20% (w/w)] in tested PCL, P-DL-LA, and PMMA biopolymers. Finally, active Ca and P ion release and corresponding hBMSC responses were most prominent in the P-DL-LA composite scaffolds. Tested 5% and 20% (w/w) Zr-ACP in P-DL-LA nanofibers appeared to release the ions at low rates and had a modest effect on OC protein levels.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by the American Dental Association Foundation.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Jin L., et al. Electrospun fibers and tissue engineering. J Biomed Nnanotechnol 8,1, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Behrens A.M., et al. In situ deposition of PLGA nanofibers via solution blow spinning. ACS Macro Lett 3,249, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Badylak S.F.The extracellular matrix as a scaffold for tissue reconstruction. Semin Cell Dev Biol 13,377, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pham Q.P., Sharma U., and Mikos A.G.Electrospinning of polymeric nanofibers for tissue engineering applications: a review. Tissue Eng 12,1197, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moroni L., De Wijn J., and Van Blitterswijk C.3D fiber-deposited scaffolds for tissue engineering: influence of pores geometry and architecture on dynamic mechanical properties. Biomaterials 27,974, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crow B., et al. Evaluation of in vitro drug release, pH change, and molecular weight degradation of poly (L-lactic acid) and poly (D, L-lactide-co-glycolide) fibers. Tissue Eng 11,1077, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hubbell J.A., Biomaterials in tissue engineering. Nat Biotechnol 13,565, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seal B., Otero T., and Panitch A.Polymeric biomaterials for tissue and organ regeneration. Mater Sci Eng R Rep 34,147, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jonoobi M., et al. Mechanical properties of cellulose nanofiber (CNF) reinforced polylactic acid (PLA) prepared by twin screw extrusion. Comp Sci Technol 70,1742, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCann J.T., Marquez M., and Xia Y.Melt coaxial electrospinning: a versatile method for the encapsulation of solid materials and fabrication of phase change nanofibers. Nano Lett 6,2868, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Teo W., and Ramakrishna S.A review on electrospinning design and nanofibre assemblies. Nanotechnology 17,R89, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nayak R., et al. Recent advances in nanofibre fabrication techniques. Text Res J 82,129, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim G., and Kim W.Highly porous 3D nanofiber scaffold using an electrospinning technique. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 81,104, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nisbet D., et al. Review paper: a review of the cellular response on electrospun nanofibers for tissue engineering. J Biomater Appl 24,7, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nam J., et al. Improved cellular infiltration in electrospun fiber via engineered porosity. Tissue Eng 13,2249, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pham Q.P., Sharma U., and Mikos A.G.Electrospun poly (ɛ-caprolactone) microfiber and multilayer nanofiber/microfiber scaffolds: characterization of scaffolds and measurement of cellular infiltration. Biomacromolecules 7,2796, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar G., et al. The determination of stem cell fate by 3D scaffold structures through the control of cell shape. Biomaterials 32,9188, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kerschnitzki M., et al. Architecture of the osteocyte network correlates with bone material quality. J Bone Miner Res 28,1837, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kerschnitzki M., et al. The organization of the osteocyte network mirrors the extracellular matrix orientation in bone. J Struct Biol 173,303, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stevens M.M., Biomaterials for bone tissue engineering. Mater Today 11,18, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim H.W., Lee H.H., and Knowles J.Electrospinning biomedical nanocomposite fibers of hydroxyapatite/poly (lactic acid) for bone regeneration. J Biomed Mater Res A 79,643, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Orrenius S., Zhivotovsky B., and Nicotera P.Regulation of cell death: the calcium–apoptosis link. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 4,552, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown E.M., and MacLeod R.J.Extracellular calcium sensing and extracellular calcium signaling. Physiol Rev 81,239, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dorozhkin S.V., and Epple M.Biological and medical significance of calcium phosphates. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 41,3130, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boskey A.L., Amorphous calcium phosphate: the contention of bone. J Dent Res 76,1433, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petite H., et al. Tissue-engineered bone regeneration. Nat Biotechnol 18,959, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ambrosio A., et al. A novel amorphous calcium phosphate polymer ceramic for bone repair: I. Synthesis and characterization. J Biomed Mater Res 58,295, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Popp J.R., et al. In vitro evaluation of osteoblastic differentiation on amorphous calcium phosphate‐decorated poly (lactic‐co‐glycolic acid) scaffolds. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 5,780, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramalingam M., et al. Nanofiber scaffold gradients for interfacial tissue engineering. J Biomater Appl 27,695, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Skrtic D., Antonucci J., and Eanes E.Amorphous Calcium Phosphate-Based Bioactive Polymeric Composites for Mineralised Tissue Regeneration. J Res 108,167, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li D., et al. Collecting electrospun nanofibers with patterned electrodes. Nano Lett 5,913, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tutak W., et al. The support of bone marrow stromal cell differentiation by airbrushed nanofiber scaffolds. Biomaterials 34,2389, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eanes E.D., Gillessen I.H., Posner A.S.Intermediate states in the precipitation of hydroxyapatite. Nature 208,365, 1965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang F., et al. Ultra‐small‐angle X‐ray scattering–X‐ray photon correlation spectroscopy studies of incipient structural changes in amorphous calcium phosphate‐based dental composites. J Biomed Mater Res A 100,1293, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Medeiros E.S., et al. Solution blow spinning: a new method to produce micro‐and nanofibers from polymer solutions. J Appl Polym Sci 113,2322, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alexis F.Factors affecting the degradation and drug‐release mechanism of poly (lactic acid) and poly [(lactic acid)‐co‐(glycolic acid)]. Polym Int 54,36, 2005 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.