Abstract

Objective

To identify when youth are most likely to start using prescription pain relievers to get high or for other unapproved indications outside the boundaries of what a prescribing physician might intend (ie, extramedical use).

Design

Cross-sectional surveys of adolescent cohorts, 2004 to 2008.

Setting

The United States.

Participants

Large nationally representative samples of youth in the United States who had been assessed for the 2004 through 2008 National Surveyon Drug Use and Health, yielding data from 138 729 participants aged 12 to 21 years.

Main Outcome Measures

Estimated age-specific risk of starting extramedical use of prescription pain relievers, year by year, and confirmation of age at peak risk by tracing the experience of individual cohorts during this period.

Results

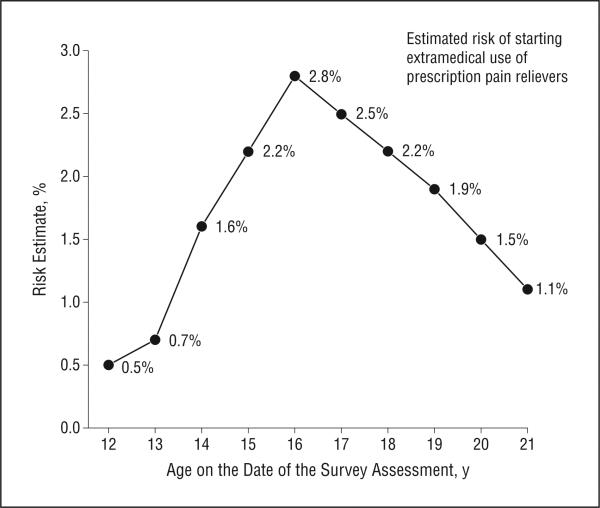

The estimated peak risk of starting extramedical use of prescription pain relievers occurs in midadolescence, well before the college years. The age at peak risk is 16 years, when an estimated 2% to 3% become newly incident users. Smaller risk estimates are observed at age 12 to 14 years and at age 19 to 21 years.

Conclusions

For initiatives to prevent youth from using prescription pain relievers to get high or for other un-approved indications, a focus on the last year of high school and the post–secondary school years may be too little too late. Practice-based approaches are needed in addition to public health interventions based on effective alcohol and tobacco prevention programs during the earlier adolescent years.

Most physicians, other clinicians who prescribe (eg, dentists), and public health professionals know about recent increasing trends of prescribing pain relievers.1 Concurrent evidence demonstrates increased use of these compounds to get high or for other unap-proved indications outside the boundaries set by prescribing clinicians (ie, extramedical use), including evidence of first use in late childhood and early adolescence.1-4 Rates of hazards, such as overdose deaths, also have increased.1

Coverage of these topics in most media outlets, press releases, journal articles, and government reports focuses attention on high school seniors and youth in the post–secondary school years. Nev ertheless, the risk of hazardous consequences may be greatest when extramedical use of prescription pain relievers starts during early adolescence.3-5

In the present study of recent experiences among individuals aged 12 to 21 years in the United States, we sought to identify when youth are most likely to start using prescription pain relievers to get high or for other unapproved indications. Based on epidemiological estimates previously published,6,7 we anticipated a peak risk late in high school or soon thereafter but made allowances for discovery of a peak risk in earlier midadolescence.4,8,9

METHODS

Data are from the 2004 through 2008 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) public use files. The NSDUH uses a cross-sectional design to select a different nationally representative random sample of the US civilian noninstitutionalized population each year. Participants in the NSDUH are 12 years or older and are interviewed once in a cross-sectional manner (ie, participants are never interviewed at a later date, as might be true in a longitudinal study). The NSDUH sampling frames include youth who drop out of school and youth who attend school. Participation levels tend to be acceptable, often at 70% or better during the years under study after parental consent and adolescent assent were secured.8 The NSDUH participants completed a standardized audio-enhanced computer-assisted self-interview (mean duration, about 60 minutes) at a private location within or near the home after informed consent processes approved by institutional review boards for protection of human participants.

One audio-enhanced computer-assisted self-interview module asked about using prescription pain relievers for the “experience or feelings” they caused or if “not prescribed for you” (ie, to get high or for other unapproved indications outside the boundaries of what the prescribing clinician might intend). Specific NSDUH modules and items are available online (http://oas.samhsa.gov/nsduh/methods.cfm). The eAppendix (http://www.archpediatrics.com) lists the standardized survey items, question prompts, and names of compounds covered.8

A total of 138 729 participants aged 12 to 21 years participated in the 2004 through 2008 NSDUH. The estimates herein are based on 119 877 participants aged 12 to 21 years whose self-report assessment indicated that they had never engaged in extramedical use of prescription pain relievers before the year in which they were assessed for the NSDUH; 18 852 participants (13.6%) did not contribute to the study estimates for incidence of use because they had already initiated such use before the year in which they were surveyed. As of the date of assessment, participants in the estimation sample were never users (who were at risk of starting use in a later year) or were newly incident users (who had just started to use). Stratum-specific estimates of the cumulative incidence proportion can be calculated as a ratio of the number of newly incident users divided by the sum of the number of never users plus the number of newly incident users. With age as a marker of cohort membership, the result is a set of risk estimates, year by year and age by age, which makes it possible to trace the experience of individual cohorts over time without a repeated-measures survey design.10 For example, the youngest cohort sampled was aged 12 years in 2004, aged 13 years in 2005, and aged 14 years in 2006. The eTable gives unweighted numbers for each numerator and denominator for each age and year cell. The eAppendix describes in detail the approach used to identify newly incident users, past-onset users, and never users.

Note that these are independently drawn nationally representative samples, year by year. A new sampling process occurs each year. As such, this project is not a longitudinal study of specific individuals with successive assessments over time, which might introduce sample attrition during the follow-up period, as well as problems such as measurement reactivity.11 Instead, the resulting cumulative incidence proportions convey the risk estimate of starting extramedical use of prescription pain relievers based on the epidemiological record of a medical outcome combined with information about the denominators at risk (such as Frost11 used in his classic epidemiological research to estimate age-specific and cohort-specific risk of tuberculosis mortality on the basis of death certificate records). A summary of other features of this research approach based on survey data has been previously published.12

Statistical analysis and an estimation approach appropriate for complex survey designs and sampling weights (representing an estimate of the total number in the target population) used commercially available software (STATA, version 11; Stata-Corp LP), with a subpopulation approach appropriate for the stratification of newly incident users, past-onset users, and never users.8 The meta-analysis summary estimates reported are not simple means; they were calculated using a random-effects meta-analysis software program (STATA, version 11) that weights each year by the inverse of its variance. Standard errors for the estimates are small because of the large NSDUH samples.

RESULTS

Table 1 summarizes the study sample. The main study estimates are given in Table 2, including tracing of individual cohorts and age-specific patterns. For example, an estimated 0.4% of participants aged 12 years in 2004 started extramedical use of prescription pain relievers. The population cohort of participants aged 12 years in 2004 was newly sampled in 2005, when the cohort passed their 13th birthdays. The risk estimate for this new sample of participants, aged 13 years in 2005, was 0.8%. Tracing the cohort diagonally in Table 2 to 2008, this cohort's risk estimate for starting extramedical use of prescription pain relievers at age 16 years is 2.5%, the largest observed value in that population cohort's series of estimates from 2004 through 2008.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 119 877 Youth After Exclusion of Individuals Who Had Previously Started Extramedical Use of Prescription Pain Relieversa

| Characteristic | Unweighted Frequency | Weighted % |

|---|---|---|

| At-risk individuals aged 12-21 y | 119 877 | 100.0 |

| Newly incident users | 2047 | 1.7 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 59 809 | 49.9 |

| Male | 60 068 | 50.1 |

| Race/ethnicityb | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 72 092 | 60.1 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 17 235 | 14.4 |

| Non-Hispanic Native American or Alaskan native | 1791 | 1.5 |

| Non-Hispanic Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 556 | 0.5 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 4032 | 3.4 |

| Non-Hispanic multirace/multiethnicity | 4111 | 3.4 |

| Hispanic | 20 060 | 16.7 |

| Population density | ||

| Metropolitan statistical area with ≥1 million | 48 934 | 40.8 |

| Metropolitan statistical area with <1 million | 55 507 | 46.3 |

| Not in a metropolitan statistical area | 15 436 | 12.9 |

| Age, y | ||

| 12 | 13 447 | 10.4 |

| 13 | 14 327 | 11.0 |

| 14 | 14 162 | 10.9 |

| 15 | 14 203 | 11.1 |

| 16 | 13 677 | 10.3 |

| 17 | 12 780 | 9.8 |

| 18 | 10 728 | 10.5 |

| 19 | 9346 | 9.1 |

| 20 | 8579 | 8.4 |

| 21 | 8628 | 8.5 |

| Year | ||

| 2004 | 23 900 | 19.6 |

| 2005 | 24 307 | 20.0 |

| 2006 | 23 808 | 20.1 |

| 2007 | 23 582 | 20.1 |

| 2008 | 24 280 | 20.2 |

Data are from the 2004 through 2008 National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

Self-reported by participants.

Table 2.

Risk Estimates by Age on the Date of the Survey Assessment for Newly Incident Extramedical Use of Prescription Pain Relievers per 100 Persons per Year Among 119 887 Youth From 2004 Through 2008a

| Risk Estimate, % by Age |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 12 y | 13 y | 14 y | 15 y | 16 y | 17 y | 18 y | 19 y | 20 y | 21 y |

| 2004 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 1.9 | 3.0 | 3.1 | 2.5 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 1.2 | 0.9 |

| 2005 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 1.4 | 2.7 | 2.8 | 2.4 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 1.3 | 1.6 |

| 2006 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 2.9 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 1.9 | 1.7 | 0.6 |

| 2007 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 2.5 | 2.7 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 1.9 | 1.0 |

| 2008 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 1.9 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.7 | 1.9 | 1.3 | 1.2 |

Data are from the 2004 through 2008 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Because of the large samples, all SEs for these estimates were below 0.1%, such that the 95% CIs of these estimates rarely overlapped.

The experience of participants aged 13 years in 2004 is similar, with a low risk estimate of 0.6% at age 13 years. The next risk estimate of 1.4% for this cohort is seen in 2005, when the cohort passed their 14th birthdays. Thereafter, the risk estimate increases to 2.0% at age 15 years in 2006. The final risk estimates are 2.5% at age 16 years in 2007 and 2.5% at age 17 years in 2008.

The experience of the cohort aged 16 years in 2004 helps to confirm that the peak risk occurs in midadolescence, before most youth in the United States have reached their senior year of high school. In 2004, an estimated 3.1% of participants aged 16 years started extramedical use of prescription pain relievers. Thereafter, the risk estimates for the cohort are 2.4% at age 17 years in 2005 and 2.4% at age 18 years in 2006, with subsequent drops to 2.1% at age 19 years in 2007 and 1.3% at age 20 years in 2008.

When Table 2 is studied year by year (row by row), the only year with a peak risk beyond age 17 years is 2008 (bottom row). For that exceptional year, the risk estimates were 2.4% for participants aged 15 years and 2.5% for participants aged 16 to 17 years. The peak risk of 2.7% in 2008 at age 18 years was not appreciably different from the 2.4% to 2.5% values.

Another notable pattern trend was observed during 2008 (bottom row of Table 2). It stands out as the year with the highest proportion of newly incident users across the 10 age groups (12-21 years) in a comparison of values across years (2004-2008) within each age group. During 2008, 6 of 10 age groups reached their peak risk or second-highest risk estimates (peak risk for ages 13, 14, and 18 years and second-highest risk estimates for ages 17, 19, and 21years).

The Figure shows meta-analysis summary estimates for age-specific risk of starting extramedical use of prescription pain relievers. Shown are the peak risks in mid-adolescence and the lower age-specific risk estimates at age 12 to 14 years and at age 19 to 21 years, which are based on all age-specific risk estimates given in Table 2, integrated via a standard meta-analysis for independently drawn study samples.

Figure.

Meta-analysis summary estimates for age-specific risk of newly incident extramedical use of prescription pain relievers. Data are from the 2004 through 2008 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (n=119 877).

COMMENT

We suspect that many physicians, other prescribing clinicians, and public health professionals will share our surprise that for youth in the United States, the peak risk of starting extramedical use of prescription pain relievers generally occurs before the final year of high school, not during the post–secondary school years. Based on this study's estimates for each year between 2004 and 2008, roughly 1 in 60 youth aged 12 to 21 years starts extramedical use of prescription pain relievers. Nonetheless, the peak risk is concentrated at about age 16 years, when roughly 1 in 30 to 40 youth starts extramedical use (meta-analysis summary estimate, 2.8%). Lower risk estimates are found for age 12 to 14 years and for age 19 to 21 years, as seen in the Figure, confirmed by tracing the experience of individual cohorts across the survey years under study (ie, diagonally in Table 2).

Before any detailed discussion or speculation about these findings, several limitations must be acknowledged, including the self-report character of the national sample survey data. Toxicological analysis remains beyond the scope of large nationally representative community samples on this scale, and it is unclear that any drug assay would eliminate uncertainty about the age of starting extramedical use of prescription pain relievers. For example, some users would have positive urine screens due to legitimately prescribed opioid use for approved indications (eg, pain relief after wisdom tooth extraction).

As another potential error, some degree of survey non-participation raises the possibility that youth with extramedical use of prescription pain relievers might not be willing to participate in surveys of this type. Nonetheless, we tried to constrain this source of error by focusing attention on youth who are just starting to use, most of whom do not develop dependence problems or become disengaged from their family or from society at large within 12 to 24 months after the onset of such use.13 In addition, a counterbalanced strength is that this survey is not restricted to youth who attend school; its sample is based on probability sampling of dwelling unit residents within each sampled community, as required for national representation of all youth. Each survey's sampling frame has included youth irrespective of whether they maintain student status, have dropped out of school, are employed in the labor force, or are unemployed.

Notwithstanding such limitations, the NSDUH estimates seem strong relative to available alternatives, but in theory useful comparative estimates might be extracted from data gathered in surveys of youth who attend school. For example, as many as 80% of youth aged 16 years in the United States have not dropped out and continue to attend secondary schools (NSDUH data not shown). As an example of other estimates of this type, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention conducts a National Youth Risk Behavior Survey, with survey questions about pain relievers introduced for the first time in 2009. The agency reported that 26% of 12th graders and 15% of 9th graders in 2009 had ever taken a prescription drug without a physician's prescription.14 However, the observed major increase from 15% to 26% across these secondary school years cannot be ascribed specifically to prescription pain relievers because the survey's single question on this topic does not distinguish prescription pain relievers from other prescribed psychoactive medicines, such as alprazolam and methylphenidate.14

By comparison, the US Monitoring the Future study9 is more informative because it asked 8th, 10th, and 12th graders about the use of narcotics other than heroin, with an explicit list that named methadone hydrochloride, codeine, pantazocine lactate (Talwin), morphine sulfate, opium, meperidine hydrochloride (Demerol), laudanum, and paregoric until 2002, when the list was expanded to include other compounds such as oxycodone (OxyContin), acetaminophen-hydrocodone (Vicodin), acetaminophen–oxycodone hydrochloride (Percocet or Percodan), and hydromorphone hydrochloride (Dilaudid), as well as (unlisted) narcotics other than heroin.

Using school survey data, we aimed to trace recent experience of individual cohorts for prescription pain relievers (eg, comparing use by 8th graders in 2004 with use by 10th graders in 2006 and with use by 12th graders in 2008), as was done in 1988 (when no correlation with age was found)15 and in recently published work on cannabis.16 However, we learned that the data for 8th and 10th graders and estimates on these compounds have not been released in the survey publications; the only data available to researchers outside the survey team are from high school seniors. The survey team acknowledges potential biases in their estimates on these topics, including the fact that the data are retrospective from 12th grade backward over time (and past onset of use might have occurred as early as the 6th grade), in addition to biases associated with absenteeism (estimated to be roughly 20% on the days of survey completion) and school dropout (estimated to be an additional 15%).9 Notwithstanding such limitations, the published data based on retrospective reports of high school seniors seems to be congruent with the evidence seen in the Figure and Table 2 herein. Specifically, in the school survey estimates from 2002 through 2009, the transition from 11th grade to 12th grade is not a marker of the peak risk. Rather, evaluated retrospectively over these years, more high school seniors had started to use narcotics other than heroin between 9th grade and 10th grade and between 10th grade and 11th grade than had been true for the transition year from 11th grade to 12th grade.9

Some prior national community sample reports,10 including an important article4 based on participants aged 12 to 17 years in the 2005 NSDUH, hinted that an incidence peak might exist in early midadolescence: 13.3 years was the estimated mean age at onset of use for youth aged 12 to 17 years who had used pain relievers during the year before NSDUH assessment.4 In contrast to research on youth aged 12 to 17 years, for whom the latest possible age at onset is 17 years, the community sample for our project included youth aged 18 to 21 years and youth aged 12 to 17 years, allowing for later onset. Perhaps most important, our project's focus was on newly incident extramedical users of prescription pain relievers (ie, youth who had just started to use these compounds during the year in which they were surveyed). When an analysis is based on all persons with a lifetime history of drug use or on all recently active users (eg, those with any use in the year before the assessment), the resulting estimates are based on the aggregate of experience across multiple cohorts and years, including the experience of drug users who have been using for many years (and who may not have a clear memory of the exact age at first use). One advantage of focusing on newly incident users is a constrained reliance on long-term memory about age at onset many years ago. In this project, the elapsed time from the initial use to the date of the interview was always constrained to be less than 12 months.

Consistent with our focus on newly incident use, we excluded 13.6% of the NSDUH participants aged 12 to 21 years during 2004 to 2008 from our estimates of cumulative incidence because they had engaged in extra-medical use of prescription pain relievers during the years before the year in which they were surveyed (and were no longer considered at risk of newly incident use). This excluded group of lifetime extramedical users of prescription pain relievers represents roughly 1 in 7 of the youth in this nationally representative sample (not including newly incident users). While such lifetime use estimates can be important indicators of the magnitude of a problem, patterns of newly incident use more clearly highlight when the most effective time might be to prevent first use or to intervene during the earliest stages of a drug dependence process.1-8,10,13,17-23

Appreciating that recent school survey data provide modest external confirmation of this project's nationally representative sample evidence, we draw attention to the timing of potential prevention and intervention approaches given the observed peak risk during midadolescence and a rise and fall of risk estimates before and after midadolescence. With the peak risk at age 16 years and a notable acceleration in risk between ages 13 and 14 years, any strict focus on college students or 12th graders might be an example of too little too late in the clinical practice sector and in public health work. There is reason to strengthen earlier school-based prevention programs and early outreach along the lines of effective school-based alcohol and tobacco public health initiatives. Even so, with as many as 15% of youth not attending school during the observed midadolescence peak risk, there also is reason to design coordinated practice-based efforts by pediatricians, dentists, and other prescribing clinicians in the patient care and public health sectors. Via coordination of school-based and practice-based initiatives, it may be possible to reduce the risks associated with youth starting to use prescription pain relievers to get high or for other unapproved indications outside the boundaries of what a prescribing clinician has intended. Of course, because an estimated 20% to 40% of high school students say that narcotics other than heroin are fairly easy or very easy to get,9,23 it is important to consider not only underuse and overuse of prescription pain relievers but also mechanisms of diversion as might be controlled in a manner that will reduce associated public health hazards.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was supported by grants R01DA016558, K05DA015799, and T32DA021129 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and by Michigan State University.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Study concept and design: Meier, Troost, and Anthony. Acquisitionofdata: Meier,Troost,and Anthony. Analysis and interpretation of data: Meier, Troost, and Anthony. Drafting of the manuscript: Meier,Troost,and Anthony. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Meier, Troost, and Anthony. Statistical analysis: Meier,Troost, and Anthony. Obtained funding: Anthony. Administrative, technical, and material support: Meier and Anthony. Study supervision: Anthony.

Additional Contributions: We thank the US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Office of Applied Studies (now the Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality) for completion of its annual nationally representative surveys on drug use and health, as well as its direction and supervision of the annual data gathering and preparation of public use data sets.

Financial Disclosure: In addition to the National Institute on Drug Abuse and Michigan State University funding/support listed herein, Dr Anthony has received payments in the form of honoraria, scientific advisory board compensation, and consultation fees for his service as a non-employee consultant of the US Food and Drug Administration and of CRS Associates, Inc, on topics pertinent to postmarketing surveillance of prescription opioids, including products by Reckitt-Benckhiser and Purdue Pharma.

Disclaimer: The content is the sole responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of Michigan State University, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, or the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Okie S. A flood of opioids, a rising tide of deaths. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(21):1981–1985. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1011512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Compton WM, Volkow ND. Major increases in opioid analgesic abuse in the United States: concerns and strategies. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;81(2):103–107. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyd CJ, Esteban McCabe S, Teter CJ. Medical and nonmedical use of prescription pain medication by youth in a Detroit-area public school district. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;81(1):37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu LT, Pilowsky DJ, Patkar AA. Non-prescribed use of pain relievers among adolescents in the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;94(1-3):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martins SS, Keyes KM, Storr CL, Zhu H, Grucza RA. Birth-cohort trends in lifetime and past-year prescription opioid-use disorder resulting from nonmedical use: results from two national surveys. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2010;71(4):480–487. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen K, Kandel DB. The natural history of drug use from adolescence to the mid-thirties in a general population sample. Am J Public Health. 1995;85(1):41–47. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kandel DB, Logan JA. Patterns of drug use from adolescence to young adulthood, I: periods of risk for initiation, continued use, and discontinuation. Am J Public Health. 1984;74(7):660–666. doi: 10.2105/ajph.74.7.660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Results From the 2008 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings . Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Office of Applied Studies; Rockville, MD: 2009. NSDUH series H-36. HHS publication SMA 09-4434. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975-2010: Volume I: Secondary School Students. Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; Ann Arbor: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kroutil L, Colliver J, Gfroerer J. Age and cohort patterns of substance use among adolescents. [March 5, 2012];OAS Data Rev. 2010 Sep;:1–9. http://www.samhsa.gov/data/2k10/DataReview/OAS_DataReview003CohortAnalysis.pdf.

- 11.Frost WH. The age selection of mortality from tuberculosis in successive decades. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;141(10):4–9. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117343. reprinted from Am J Hyg. 1939;30:91-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anthony JC. Novel phenotype issues raised in cross-national epidemiological research on drug dependence. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1187:353–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05419.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen CY, Storr CL, Anthony JC. Early-onset drug use and risk for drug dependence problems. Addict Behav. 2009;34(3):319–322. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2009. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2010;59(5):1–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Johnston LD. Period, age, and cohort effects on substance use among young Americans: a decade of change, 1976-86. Am J Public Health. 1988;78(10):1315–1321. doi: 10.2105/ajph.78.10.1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keyes KM, Schulenberg JE, O’Malley PM, et al. The social norms of birth cohorts and adolescent marijuana use in the United States, 1976-2007. Addiction. 2011;106(10):1790–1800. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03485.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bohnert AS, Valenstein M, Bair MJ, et al. Association between opioid prescribing patterns and opioid overdose-related deaths. JAMA. 2011;305(13):1315–1321. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCabe SE, Boyd CJ, Cranford JA, Teter CJ. Motives for nonmedical use of prescription opioids among high school seniors in the United States: self-treatment and beyond. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(8):739–744. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singer N. Taking the fun out of popping pain pills. New York Times; Sep 19, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCauley JL, Amstadter AB, Macdonald A. Non-medicaluseofprescriptiondrugs in a national sample of college women. Addict Behav. 2011;36(7):690–695. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anthony J, Warner L, Kessler R. Comparative epidemiology of dependence on tobacco, alcohol, controlled substance and inhalants: basic findings from the National Comorbidity Survey. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 1994;2(3):244–268. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu LT, Woody GE, Yang C, Pan JJ, Blazer DG. Abuse and dependence on prescription opioids in adults: a mixture categorical and dimensional approach to diagnostic classification. Psychol Med. 2011;41(3):653–664. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710000954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arria AM, Garnier-Dykstra LM, Caldeira KM, Vincent KB, O'Grady KE. Prescription analgesic use among young adults: adherence to physician instructions and diversion. Pain Med. 2011;12(6):898–903. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01107.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.