Abstract

Background and Purpose

miR-200c increases rapidly in the brain following transient cerebral ischemia but its role in post-stroke brain injury is unclear. Reelin, a regulator of neuronal migration and synaptogenesis, is a predicted target of miR-200c. We hypothesized that miR-200c contributes to injury from transient cerebral ischemia by targeting reelin.

Methods

Brain infarct volume, neurological score and levels of miR-200c, reelin mRNA and reelin protein were assessed in mice subjected to 1 hr of middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) with/without intracerebroventricular infusion of miR-200c antagomir, mimic or mismatch control. Direct targeting of reelin by miR-200c was assessed in vitro by dual luciferase assay and immunoblot.

Results

Pre-treatment with miR-200c antagomir decreased post-MCAO brain levels of miR-200c, resulting in a significant reduction in infarct volume and neurologic deficit. Changes in brain levels of miR-200c inversely correlated with reelin protein expression. Direct targeting of the Reln 3’UTR by miR-200c was verified with dual luciferase assay. Inhibition of miR-200c resulted in an increase in cell survival subsequent to in vitro oxidative injury. This effect was blocked by knockdown of reelin mRNA, while application of reelin protein afforded protection.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that the post-stroke increase in miR-200c contributes to brain cell death by inhibiting reelin expression, and that reducing post-stroke miR-200c is a potential target to mitigate stroke induced brain injury.

Keywords: microRNA, stroke, ischemia-reperfusion injury, MCAO

Introduction

MicroRNAs (miRs) are endogenous, short (~20 nucleotides) single-stranded RNAs that regulate gene expression by inhibiting translation of specific target mRNAs. Members of the miR-200 family are upregulated in the brain following transient cerebral ischemia (1), but their role in stroke-related injury is not understood. Studies in tumor and endothelial cells demonstrate a pro-apoptotic role for miR-200c (2–4), suggesting that post-stroke increases in miR-200c may contribute to neuronal cell death.

Computational analysis of potential neuronal targets of miR-200c identifies reelin, an extracellular matrix protein essential for proper neuronal migration in the developing brain (5, 6) and in maintaining synaptogenesis in adulthood (7). Reelin coordinates neuronal cell survival by inhibiting apoptosis (8), and may play a protective role in the response to cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury, as reelin-deficient mice are more susceptible to injury following transient cerebral ischemia (9). Therefore, in the present study we sought to determine: 1) whether miR-200c contributes to brain cell death subsequent to transient cerebral ischemia; 2) whether reducing miR-200c with antagomir pre-treatment could decrease the severity of acute stroke injury; and 3) whether the effect of miR-200c on neuronal cell death is mediated by inhibition of reelin.

Methods

More details are provided in the online-only Data Supplement

Animals and in vivo Experimental Protocols

All experimental protocols using animals were approved by the Stanford University Animal Care and Use Committee, and in accordance with NIH guidelines. Adult male CB57/B6 mice (age 8–10 wks, Charles River) were randomly assigned by coin flip to either intracerebroventricular (ICV) pre-treatment with miR-200c antagomir, mimic or mismatch-control and subjected to 1 hr middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO). Neurologic score and infarct volume were assessed by a blinded observer after 24 hrs of reperfusion. In a second set of experiments, animals were randomly divided and pre-treated with either ICV miR-200c antagomir or control infusion 24 hrs prior to 1 hr MCAO, and then sacrificed at 1, 3 and 24 hrs of reperfusion for analysis of brain levels of miR-200c, reelin mRNA, and reelin protein.

Intracerebroventricular (ICV) Pre-treatment

Mice were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane by facemask and placed in a stereotaxic frame. A 26-gauge brain infusion cannula was placed stereotaxically into the left lateral ventricle (bregma: − 0.58 mm; dorsoventral: 2.1 mm; lateral: 1.2 mm) as previously described (10). miR-200c antagomir (3 pmol/g body weight in 2 µL), mimic or mismatch-control (Life Technologies) was mixed with cationic lipid DOTAP (4µl; 6 µl total volume; Roche) and infused over 20 min.

Transient Focal Cerebral Ischemia (MCAO)

Mice (n = 124 for all treatment groups and analyses) were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane and focal cerebral ischemia was produced by 1 hr of MCAO with a 6–0 monofilament followed by reperfusion as previously described (10, 11). Sham-operated mice (n=12) underwent ligation of the external carotid artery but no suture insertion. Temperature and respiratory rate were monitored continuously and rectal temperature was maintained at 37 ± 0.5 °C with a heating pad. After the appropriate duration of reperfusion, mouse brains were rapidly removed following transcardial perfusion with ice cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS to assess infarct volume, or after perfusion only with PBS for RT-qPCR or protein analysis. Mice with no evidence of acute neurological deficit (control = 3/24, antagomir = 2/14, mimic = 2/14), that died < 24 hr following surgery (control = 3/50, antagomir = 4/48, mimic = 1/17), or with evidence of significant bleeding (control = 6/50, antagomir = 7/48, mimic = 2/17) were excluded from analysis. No significant difference (p<0.05) was observed between treatment groups in number of excluded animals.

Neurologic Score and Measurement of Cerebral Infarction Area

Neurologic performance was assessed and scored prior to sacrifice as previously described (10) from a score of 0 (no observable neurological deficit) to 4 (unable to walk spontaneously). Mice were then deeply anesthetized and transcardially perfused with saline followed by 4% paraformaldehyde, and brains were removed. Following coronal sectioning of brains into 50 µm sections with a vibratome and staining with Cresyl Violet (EMD Chemicals), infarct volume was quantified by a blinded observer and corrected for edema using Image J software (v1.46, National Institutes of Health) as described previously (11).

Dual Luciferase Target Validation and Reporter Assay

The luciferase reporter assay was performed as described previously (12). Briefly, mouse neuroblastoma (N2a) cells were co-transfected with 0.25 ng Firefly luciferase control reporter plasmid, 0.05 ng Renilla luciferase target reporter with Reln 3’UTR, and 40 ng miRNA expression vector using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Luminescence was assessed using a Promega Dual-Luciferase assay kit (E1960) with automated microplate reader (Infinite M1000 Pro, Tecan). In an additional set of experiments, we tested a second potential target of miR-200c identified by computational predictive algorithms (Targetscan.org, release v6.2), Grp75 (Hsp9a/Hsp75/mortalin), a mitochondrial-localized member of the HSP70 family known to play a role in neuroprotection (13).

Cell Culture Transfection and Injury

N2a cells were grown in high-glucose DMEM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad) supplemented with 8% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone) and antibiotics (50 U/mL penicillin + 50µg/mL streptomycin; Invitrogen) in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Cells were transfected with 20 pmol miR-200c mimic, inhibitor, or mismatch-control (Thermo Scientific), with and without 20 pmol Reln siRNA (Life Technologies) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Cells were either harvested for analysis of miR-200c, reelin mRNA or reelin protein, or subjected to injury 24 hrs following transfection. In an additional set of experiments, cells were incubated with 0, 50, 100 or 500 ng/µL recombinant reelin protein 1 hr prior, and during, injury. Injury was induced by exposure to 500 µM H2O2 in serum-free DMEM for either 18 or 24 hrs (14) and cell death was quantified by measuring lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) released dead cells as previously described (15).

Reverse Transcription Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated with TRIzol® (Invitrogen). Reverse transcription was performed as previously described (16) using the TaqMan MicroRNA Reverse Transcription Kit for miR-200c and total RNA (Applied Biosystems). Predesigned primer/probes for PCR were obtained from Life Technologies for mouse Reln and GAPDH mRNA, miRNA-200c, and U6 small nuclear RNA (U6). qPCR reactions were conducted as previously described (16) using the TaqMan® Assay Kit (Applied Biosystems). Measurements for reelin mRNA were normalized to within-sample GAPDH, while miR-200c was normalized to U6 (ΔCt). Comparisons were calculated as the inverse log of the ΔΔCT from controls (17).

Reelin Protein Analysis

Immunoblotting was performed as previously described (11). Briefly, 50 µg of protein/sample was separated on a 4–10% Bis-Tris mini-gel (Life Technologies), and electrotransferred to Immobilon polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Millipore Corp.). Membranes were blocked and incubated with primary antibody against full-length reelin (1:500, Abcam, #ab78540) and β-actin (1:3000, LiCOR Bioscience, #926–42210), washed and incubated with 1:15,000 the appropriate conjugated secondary antibody (LiCOR Bioscience, #926–32212, #926–68021). Immunoreactive bands were visualized using the LICOR Odyssey infrared imaging system. Densitometric analysis was performed using Image J software (v1.46, National Institutes of Health). Reelin band intensity was normalized to β-actin.

Statistical Analysis

All cell culture data represent at least three independent experiments. All data reported are mean ± sem. Statistical analysis was performed using t-test if only two conditions, or one-way analysis of variance with the Bonferroni post-test for multiple comparisons. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered significant in all analyses.

Results

Reduction of miR-200c Protects the Brain from Transient Focal Cerebral Ischemia

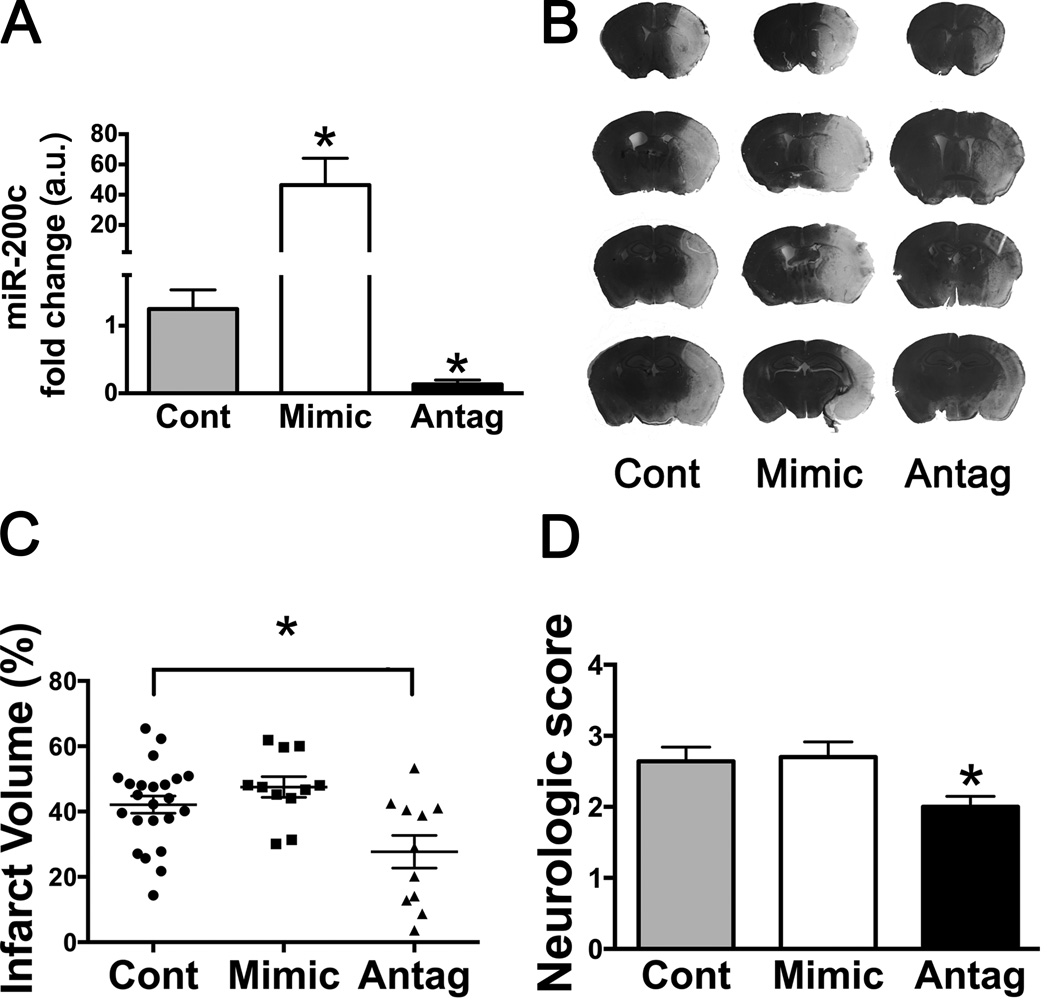

Decreasing miR-200c has been shown to improve cell survival following in vitro ischemia in neuronal SH-SY5Y cells (18). We investigated the effect of miR-200c inhibition in transient focal cerebral ischemia. Pre-treatment with ICV infusion of miR-200c antagomir resulted in significant knockdown of miR-200c to ~13% of control values, while pre-treatment with miR-200c mimic increased miR-200c approximately 40-fold (Figure 1A). After miR-200c antagomir pre-treatment and MCAO infarct volume was significantly decreased, about 30% relative to control animals (Figures 1B and 1C). Gross motor function, estimated by neurological score 24 hrs following reperfusion, was significantly improved with antagomir pre-treatment (Figure 1D). In contrast animals pre-treated with miR-200c mimic were not significantly different from mismatch control in either infarct volume or neurologic score.

Figure 1.

A, Brain miR-200c levels following intracerebroventricular (ICV) pre-treatment decrease with miR-200c antagomir and increase with mimic, relative to mismatch-control (Control). B, Representative Cresyl Violet stained brain sections from mice subjected to ICV pre-treatment, 1 hr MCAO, and 24 hrs of reperfusion. Regions of infarct are lighter in color. C, Effect of altering miR-200c levels on injury: quantification of infarct volume averaged over 4 levels demonstrated significant protection with miR-200c antagomir (Antag) pre-treatment compared to either Control or Mimic. D, Neurologic score in post-MCAO mice: miR-200c antagomir pre-treatment resulted in significantly improved neurologic outcome (lower score). * = p < 0.05 compared to control; n = 11–23 animals/group.

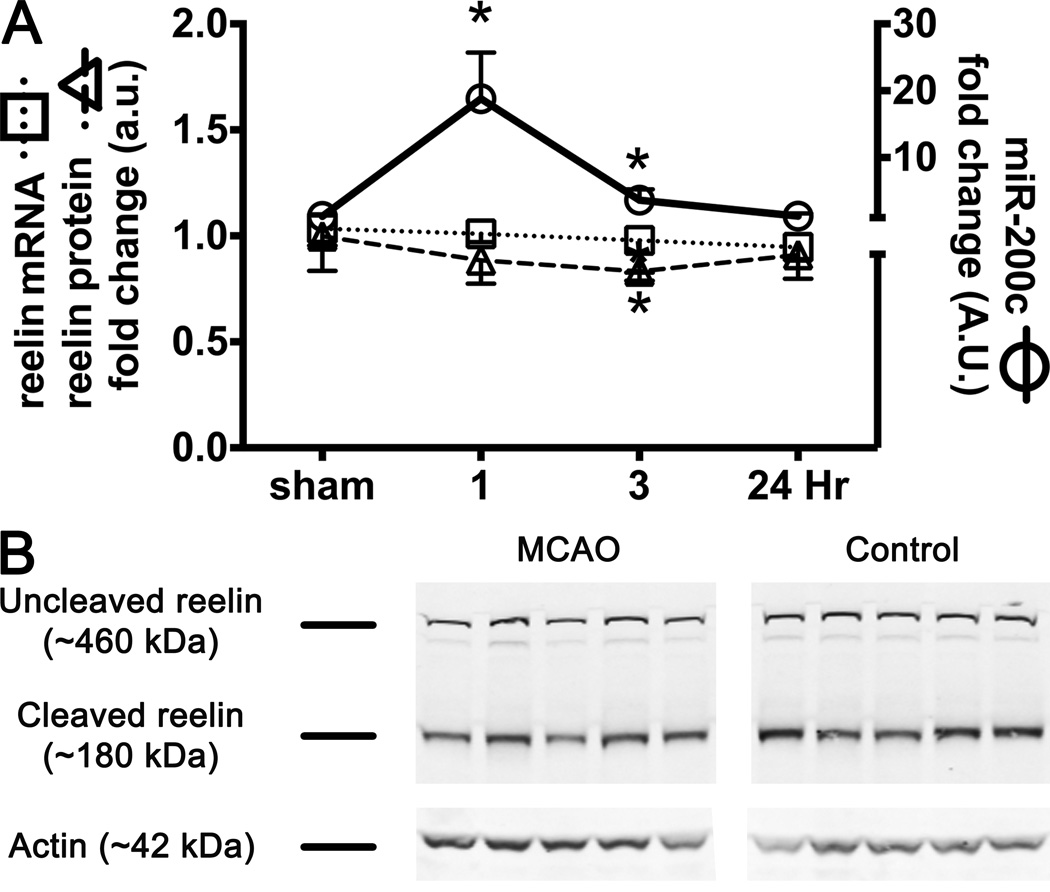

Brain Levels of Reelin Decrease Following MCAO

Brain levels of miR-200c after MCAO significantly increased approximately 17-fold at 1 hr of reperfusion [(Figure 2A ( )], before returning to baseline levels by 24 hrs of reperfusion. Conversely, by 3 hrs of reperfusion brain levels of reelin protein were significantly decreased [(Figure 2A (

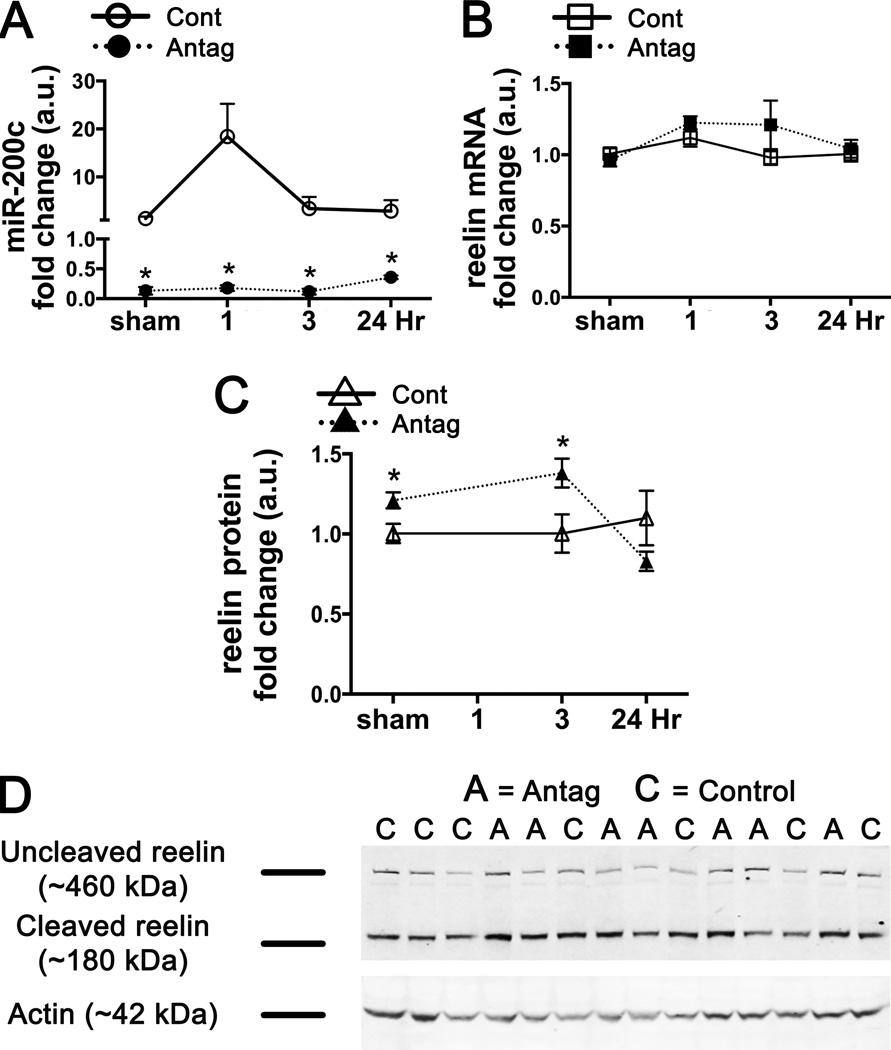

)], before returning to baseline levels by 24 hrs of reperfusion. Conversely, by 3 hrs of reperfusion brain levels of reelin protein were significantly decreased [(Figure 2A ( ), 2B)]. These findings agree with previous data showing an inverse correlation between reelin and miR-200c expression in developing submandibular cells (19). To further define a functional relationship between miR-200c and reelin in the development of injury following transient cerebral ischemia, we assessed post-MCAO brain levels of reelin mRNA and uncleaved reelin protein in animals subjected to miR-200c knockdown prior to MCAO. We observed a significant decrease in miR-200c with antagomir relative to mismatch-control pre-treated animals at baseline and all reperfusion time-points (Figure 3A). An effect of miR-200c knockdown on reelin expression was also observed: both pre-MCAO levels and levels at the 3 hr reperfusion time-point in miR-200c antagomir pre-treated animals demonstrated significantly increased reelin protein (Figures 3C and 3D). However, miR-200c suppression by antagomir did not alter reelin mRNA levels (Figure 3B), suggesting that inhibition of reelin expression by miR-200c occurred via translational silencing rather than mRNA degradation.

), 2B)]. These findings agree with previous data showing an inverse correlation between reelin and miR-200c expression in developing submandibular cells (19). To further define a functional relationship between miR-200c and reelin in the development of injury following transient cerebral ischemia, we assessed post-MCAO brain levels of reelin mRNA and uncleaved reelin protein in animals subjected to miR-200c knockdown prior to MCAO. We observed a significant decrease in miR-200c with antagomir relative to mismatch-control pre-treated animals at baseline and all reperfusion time-points (Figure 3A). An effect of miR-200c knockdown on reelin expression was also observed: both pre-MCAO levels and levels at the 3 hr reperfusion time-point in miR-200c antagomir pre-treated animals demonstrated significantly increased reelin protein (Figures 3C and 3D). However, miR-200c suppression by antagomir did not alter reelin mRNA levels (Figure 3B), suggesting that inhibition of reelin expression by miR-200c occurred via translational silencing rather than mRNA degradation.

Figure 2.

A, Time course of brain levels of miR-200c ( ), reelin mRNA (

), reelin mRNA ( ) and uncleaved reelin protein (

) and uncleaved reelin protein ( ) in mice subjected to 1 hr MCAO. B, Examples of immunoblots for reelin and actin following middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) at the 3 hr reperfusion time point. While levels of miR-200c increased by 1 hr of reperfusion (A), levels of uncleaved reelin protein (A, B) decreased by 3 hrs, suggesting translational inhibition. * = p < 0.05 compared to sham control; n = 8 animals/group.

) in mice subjected to 1 hr MCAO. B, Examples of immunoblots for reelin and actin following middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) at the 3 hr reperfusion time point. While levels of miR-200c increased by 1 hr of reperfusion (A), levels of uncleaved reelin protein (A, B) decreased by 3 hrs, suggesting translational inhibition. * = p < 0.05 compared to sham control; n = 8 animals/group.

Figure 3.

In mice pre-treated with ICV infusion of miR-200c antagomir, post-MCAO miR-200c expression in the brain significantly decreased relative to control (A). Although reelin mRNA remained unchanged (B), uncleaved reelin protein increased (C, D), suggesting silencing by miR-200c rather than degradation. * = p < 0.05 compared to pre-MCAO control; n = 8–11 animals/group.

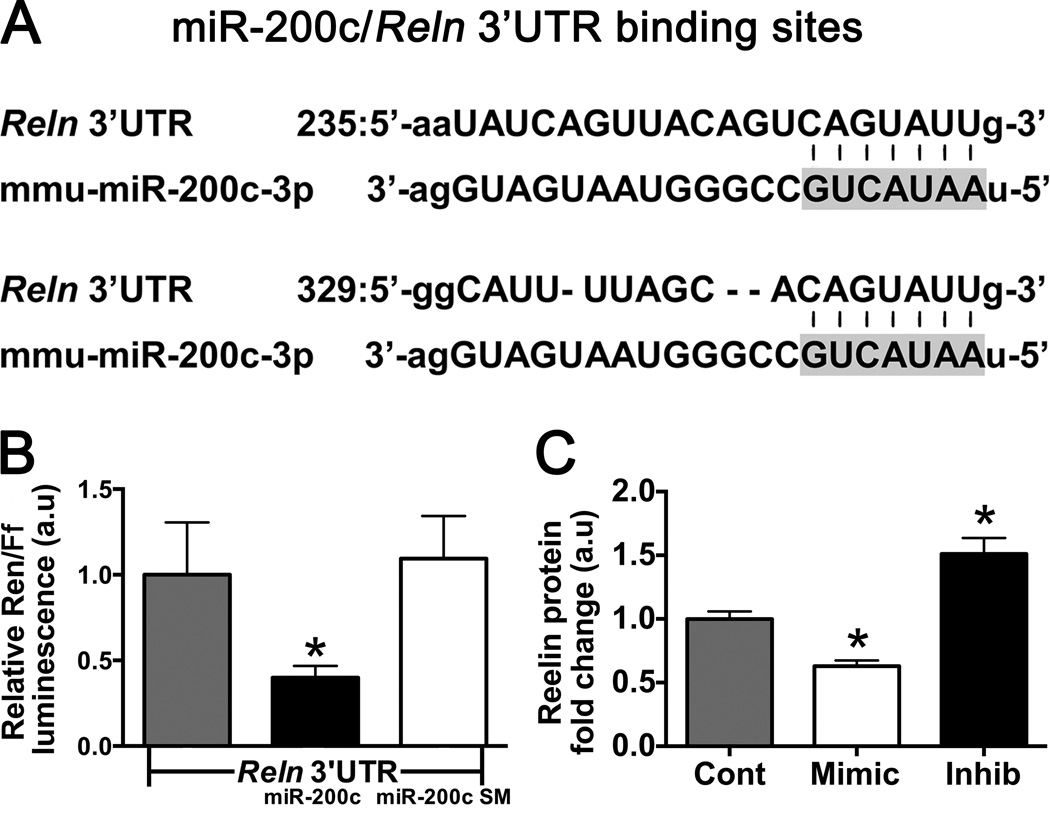

Validation of the 3’UTR of Reln as a Direct Target of miR-200c

To date, only predictive and correlative evidence (19) has been presented suggesting reelin mRNA is a direct target of miR-200c (mature miR-200c sequence listed in Supplemental Figure IA). The 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of Reln contains two potential binding sites for miR-200c (Targetscan.org, release v6.2; Fig 4A). To validate direct targeting of the Reln 3′UTR by miR-200c we utilized the dual luciferase gene reporter assay in N2a cells. The full-length mouse Reln 3’UTR (1119 nt) was cloned (forward primer: GGACTTGGCGAACAGAAAGC; reverse primer: CTAGTCAGAGGCTACAGGGC) and inserted into the Renilla luciferase reporter vector phRL-TK (Promega). We generated a mutant of mouse miR-200c with 3 base substitutions within the seed region (nt 47–53 of the mouse sequence, AAUACUG to AAAAGUC). Both wildtype and mutant inserts were confirmed by DNA sequencing (Stanford Protein and Nucleic Acid Facility). Luciferase activity with the 3′UTR of Reln present was significantly decreased by exposure to miR-200c compared to the miR-200c seed mutant control (Fig 4B). We further assessed the effect of miR-200c levels on reelin protein expression in N2a cells by immunoblot after changing levels with miR-200c mimic, inhibitor or mismatch-control. Transfection with miR-200c mimic significantly decreased, and inhibitor significantly increased, reelin protein expression (Figure 4C), indicating that the luciferase data is also reflected in changes in protein levels in this cell line.

Figure 4.

Reln 3’UTR is a direct target of miR-200c. Predicted binding for miR-200c:Reln 3’UTR (A) was assessed by dual luciferase activity assay in N2a cells co-transfected with Renilla (Ren) Reln 3′UTR target reporter, Firefly (Ff) control reporter, plus either wild type miR-200c or seed mutant (SM). A reduction in luciferase activity with wild type but not SM control indicated that miR-200c recognizes the Reln 3′UTRs (B). Uncleaved reelin protein expression (C) decreases in N2a cells treated with mimic, and increases in cells treated with inhibitor, relative to mismatch control-treated cells. All cell culture experiments were performed in triplicate, * = p < 0.05 compared to control, n= 4–6 wells/condition.

We tested a second potential target of miR-200c predicted by homology, the mitochondrial chaperone Grp75 (Hsp9a). The 3’UTR of Hsp9a shares the same seed sequence homology with miR-200c as the Reln 3’UTR (Supplemental Figure IB). The Hsp9a 3’UTR was cloned (primers listed in Supplemental Figure IC) and assessed with dual luciferase assay. In N2a cells, dual luciferase assay with the Hsp9a 3’UTR and miR-200c yielded no change in luciferase activity (Supplemental Figure ID), indicating that Grp75 is likely not a direct target of miR-200c in these cells.

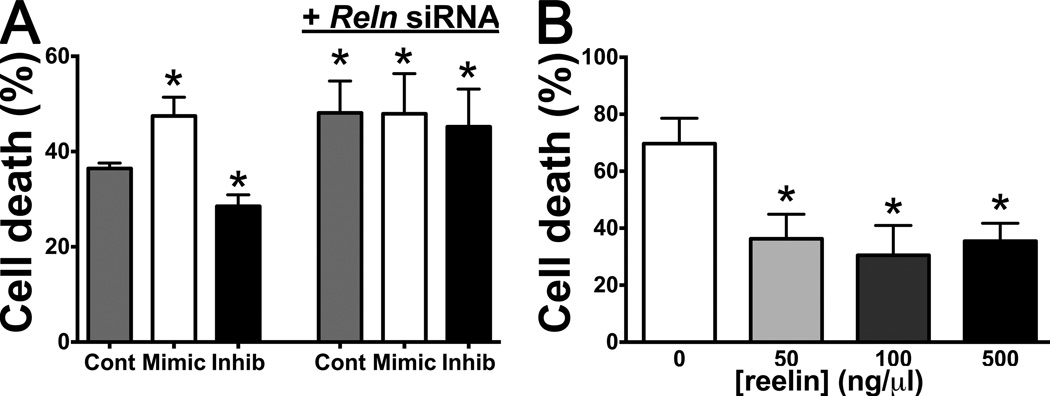

miR-200c Contributes to Neuronal Cell Death by Inhibiting Reelin Expression

Because miRs can theoretically target a large number of different genes, we investigated whether reduction of reelin expression by miR-200c might be a mechanism contributing to cell death. We compared cells with increased or decreased levels of miR-200c using mimic and inhibitor. Cultures were also treated with siRNA to Reln or control to reduce reelin mRNA expression. After altering miR-200c levels using mimic and inhibitor (2513 ± 113 and 0.68 ± 0.06 fold change respectively, relative to control), N2a cells were subjected to 500 µM H2O2 exposure in serum-free medium for 18 hrs and assayed for cell death. Inhibition of miR-200c significantly decreased, while miR-200c mimic increased, cell death from this injury paradigm (Figure 5A). Reelin mRNA was effectively decreased (to 0.22 ± 0.05) with siRNA to Reln, and this abolished the protective effect of miR-200c inhibition (Figure 5A), confirming a role for reelin in the mechanism of miR-200c-mediated cell death. Finally, exogenous application of recombinant reelin at 50, 100 or 500 ng/µl provided significant protection (Figure 5B) from 24 hrs of H202/serum deprivation.

Figure 5.

A, Cell death following in vitro reperfusion injury (18 hrs serum deprivation plus 500 µM H2O2) increased in cells transfected with miR-200c mimic but decreased with miR-200c inhibitor. Co-transfection with Reln siRNA abolished the protective effect of miR-200c inhibition. B, Cell death following 24 hrs serum-deprivation plus 500 µM H2O2 was significantly attenuated by application of recombinant reelin protein. All cell culture experiments were performed in triplicate, * = p < 0.05 compared to control, n= 8 wells/condition.

Discussion

In the present study, we investigated the role of miR-200c in the evolution of injury following transient cerebral ischemia by altering brain levels of miR-200c prior to transient focal cerebral ischemia. Using antagomir pre-treatment, we have demonstrated for the first time that preventing the early increase in miR-200c in the brain subsequent to transient focal cerebral ischemia is protective. We confirmed the protective effect of miR-200c knockdown in an in vitro model using oxidative stress.

We most consistently observed a protective effect with miR-200c inhibition, although increasing levels with miR-200c mimic did not result in further injury in vivo. This may be due to the high endogenous post-stroke levels of miR-200c, whereby any further increase with mimic did not result in additional translational suppression. Previous studies investigating the role of miR-200c in neuronal injury have reported varying outcomes. Lee et al. demonstrated that inhibition of miR-200c decreased cell death following in vitro ischemia in neuronal SH-SY5Y cells (18). This finding agrees with several previous studies (2–4) in other cells implicating miR-200c as contributing to cell death by targeting and silencing anti-apoptotic genes. However, increased survival subsequent to in vitro ischemia in the absence of reperfusion was also reported with overexpression of miR-200c (18). These seemingly conflicting results may be due to different ischemic injury protocols; previous findings indicate that brain levels of miR-200c increase substantially 3 hrs following a transient period of ischemia, but not following a 3 hr period of fixed ischemia (1), suggesting that reperfusion may be an important component in miR-200c induction and function. This agrees with previous findings in endothelial cells where oxidative stress induced increased expression of miR-200c, causing apoptosis and growth arrest (4).

A second major finding of this study is that reelin is a direct target of miR-200c, and that reduction of reelin by miR-200c with antagomir pre-treatment contributes at least in part to stroke-related injury. In the present study, we observed only a modest and transient increase in reelin expression in vivo following miR-200c suppression with antagomir, which may be the result of cell-type or regional heterogeneity in reelin expression, and/or additional cellular factors regulating reelin expression (20). The half-life of antagomir to miR-200c is not known, so the decrease in reelin expression at 24 hrs may also be due to loss of antagomir. However, our observations in cell culture demonstrated a greater alteration in reelin expression with changing levels of miR-200c, supporting our findings using the dual luciferase assay that reelin is a direct target of miR-200c. Since additional targets of miR200c may be relevant for stroke, future studies will need to knockdown specific targets to assess their relevance for protection.

While previous studies have established the role of reelin in neurodevelopment (21), little is known regarding the functional role reelin plays in neuroprotection. Reelin deficient mice provide a loss-of-function model but display early neurological dysfunction and greater susceptibility to excitotoxicity (9), and it is currently unknown if they develop compensatory changes in cell survival signaling which could complicate interpretation of results using these mice. Therefore we performed in vitro reelin loss-of-function experiments using siRNA to demonstrate that the protective effect of miR-200c inhibition is lost when reelin expression is concurrently downregulated. Moreover, our findings demonstrate for the first time that exogenous application of recombinant reelin provides significant protection from oxidative injury in vitro, highlighting a possible clinical role for reelin in the acute phase of stroke treatment. As the role of reelin in modulating neuronal growth is well-established, future studies investigating the utility of post-treatment interventions modulating miR-200c and/or reelin levels may prove interesting and relevant to future clinical treatment and recovery. While we did not investigate the intracellular mechanisms contributing to reelin-mediated cytoprotection, previous studies demonstrate that reelin triggers disabled-1 (Dab-1) phosphorylation and downstream activation of the pro-growth and pro-survival PI3K/Akt pathway through both canonical [via apoER2 and VLDLR activation (22)] and non-canonical [α3β1integrin (23)/cadherin-related neuronal receptor (24)] signaling pathways, ultimately contributing to maintenance of mitochondrial homeostasis. In vivo, reelin may also indirectly promote neuronal cell survival via glia-mediated mechanisms: reelin binds and activates Dab-1 in radial glial cells, astrocyte precursor cells traditionally viewed as providing neuronal support and guidance primarily during embryonic development (25). Recent evidence suggests that radial glia persist and proliferate in the adult brain (26). Moreover, terminally differentiated astrocytes may have the capacity to reactivate their stem cell potential following injury, helping to protect and repair adult neurons (27). Extending the findings in the present study to investigations delineating the mechanisms of reelin-mediated neuronal protection and neuron-glial coupling and differentiation may yield further insight into potential future therapies for stroke.

In summary, the major novel findings of this study are: 1) brain levels of miR-200c influence injury severity following MCAO; 2) reducing levels of miR-200c with antagomir reduces infarct size and improves neurobehavioral outcome; 3) miR-200c directly targets reelin expression; 4) miR-200c regulation of neuronal cell survival occurs, at least in part, by altered reelin expression; and 5) treatment with reelin protein promotes neuronal cell survival. These results suggest that inhibiting brain levels of miR-200c and/or upregulating reelin expression in the acutely injured brain may have clinical utility to both minimize the evolution of injury and enhance recovery.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank William Magruder for assistance in manuscript preparation, and Jeong-mi Moon, MD, for assistance with the N2a cell injury model.

Sources of Funding

Supported by American Heart Association 14FTF-19970029 and National Institutes of Health T32-GM089626 awarded to CMS and National Institutes of Health R01-NS084396 to RGG.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None

References

- 1.Lee ST, Chu K, Jung KH, Yoon HJ, Jeon D, Kang KM, et al. MicroRNAs induced during ischemic preconditioning. Stroke. 2010;41:1646–1651. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.579649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schickel R, Park SM, Murmann AE, Peter ME. miR-200c regulates induction of apoptosis through CD95 by targeting FAP-1. Mol Cell. 2010;38:908–915. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen CH, Xiao WW, Jiang XB, Wang JW, Mao ZG, Lei N, et al. A novel marine drug, SZ-685C, induces apoptosis of MMQ pituitary tumor cells by downregulating miR-200c. Curr Med Chem. 2013;20:2145–2154. doi: 10.2174/0929867311320160007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Magenta A, Cencioni C, Fasanaro P, Zaccagnini G, Greco S, Sarra-Ferraris G, et al. miR-200c is upregulated by oxidative stress and induces endothelial cell apoptosis and senescence via ZEB1 inhibition. Cell Death Differ. 2011;18:1628–1639. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D’Arcangelo G, Miao GG, Chen SC, Soares HD, Morgan JI, Curran T. A protein related to extracellular matrix proteins deleted in the mouse mutant reeler. Nature. 1995;374:719–723. doi: 10.1038/374719a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rice DS, Sheldon M, D’Arcangelo G, Nakajima K, Goldowitz D, Curran T. Disabled-1 acts downstream of Reelin in a signaling pathway that controls laminar organization in the mammalian brain. Development. 1998;125:3719–3729. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.18.3719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pujadas L, Gruart A, Bosch C, Delgado L, Teixeira CM, Rossi D, et al. Reelin regulates postnatal neurogenesis and enhances spine hypertrophy and long-term potentiation. J Neurosci. 2010;30:4636–4649. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5284-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohkubo N, Vitek MP, Morishima A, Suzuki Y, Miki T, Maeda N, et al. Reelin signals survival through Src-family kinases that inactivate BAD activity. J Neurochem. 2007;103:820–830. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Won SJ, Kim SH, Xie L, Wang Y, Mao XO, Jin K, et al. Reelin-deficient mice show impaired neurogenesis and increased stroke size. Exp Neurol. 2006;198:250–259. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiong X, Barreto GE, Xu L, Ouyang YB, Xie X, Giffard RG. Increased brain injury and worsened neurological outcome in interleukin-4 knockout mice after transient focal cerebral ischemia. Stroke. 2011;42:2026–2032. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.593772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Han RQ, Ouyang YB, Xu L, Agrawal R, Patterson AJ, Giffard RG. Postischemic brain injury is attenuated in mice lacking the β2-adrenergic receptor. Anesth Analg. 2009;108:280–287. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e318187ba6b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trujillo RD, Yue SB, Tang Y, O’Gorman WE, Chen CZ. The potential functions of primary microRNAs in target recognition and repression. EMBO J. 2010;29:3272–3285. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu L, Voloboueva LA, Ouyang Y, Emery JF, Giffard RG. Overexpression of mitochondrial Hsp70/Hsp75 in rat brain protects mitochondria, reduces oxidative stress, and protects from focal ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29:365–374. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moon JM, Xu L, Giffard RG. Inhibition of microRNA-181 reduces forebrain ischemia-induced neuronal loss. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33:1976–1982. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu L, Koumenis IL, Tilly JL, Giffard RG. Overexpression of bcl-xL protects astrocytes from glucose deprivation and is associated with higher glutathione, ferritin, and iron levels. Anesthesiology. 1999;91:1036–1046. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199910000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ouyang YB, Lu Y, Yue S, Xu LJ, Xiong XX, White RE, et al. miR-181 regulates GRP78 and influences outcome from cerebral ischemia in vitro and in vivo. Neurobiol Dis. 2012;45:555–563. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-ΔΔ CT) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee YJ, Johnson KR, Hallenbeck JM. Global protein conjugation by ubiquitin-like-modifiers during ischemic stress is regulated by microRNAs and confers robust tolerance to ischemia. PLoS One. 2012;7:e47787. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rebustini IT, Hayashi T, Reynolds AD, Dillard ML, Carpenter EM, Hoffman MP. miR-200c regulates FGFR-dependent epithelial proliferation via Vldlr during submandibular gland branching morphogenesis. Development. 2012;139:191–202. doi: 10.1242/dev.070151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abraham H, Meyer G. Reelin-expressing neurons in the postnatal and adult human hippocampal formation. Hippocampus. 2003;13:715–727. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fatemi SH. Reelin glycoprotein: structure, biology and roles in health and disease. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10:251–257. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bock HH, Jossin Y, Liu P, Forster E, May P, Goffinet AM, et al. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase interacts with the adaptor protein Dab1 in response to Reelin signaling and is required for normal cortical lamination. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:38772–38779. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306416200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dulabon L, Olson EC, Taglienti MG, Eisenhuth S, McGrath B, Walsh CA, et al. Reelin binds α3β1 integrin and inhibits neuronal migration. Neuron. 2000;27:33–44. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Senzaki K, Ogawa M, Yagi T. Proteins of the CNR family are multiple receptors for Reelin. Cell. 1999;99:635–647. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81552-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rakic P. Guidance of neurons migrating to the fetal monkey neocortex. Brain Res. 1971;33:471–476. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(71)90119-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kriegstein A, Alvarez-Buylla A. The glial nature of embryonic and adult neural stem cells. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2009;32:149–184. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robel S, Berninger B, Gotz M. The stem cell potential of glia: lessons from reactive gliosis. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12:88–104. doi: 10.1038/nrn2978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.