Abstract

Objective

To examine whether longitudinal urinary incontinence (UI) characteristics, race or ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and education were associated with UI treatment-seeking in a prospective cohort of community-dwelling midlife women.

Methods

We analyzed data from 9 years of the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN). The study asked participants reporting at least monthly UI about seeking treatment for their UI at baseline and in visit years 7, 8 and 9. Our main covariates included self-reported race or ethnicity, income, level of difficulty paying for basics, and education level. We used multiple logistic regression to examine associations between demographic, psychosocial, and longitudinal UI characteristics and whether women sought UI treatment. We explored interactions by race or ethnicity, socioeconomic status measures, and education level.

Results

A total of 1550 women (68% of women with UI) reported seeking treatment for UI over the 9 years of this study. In multivariable analyses, women had higher odds of seeking treatment when UI in the year prior to seeking treatment was more frequent (adjusted odds ratio (aOR) 3.16, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.15–8.67) and more bothersome (aOR 1.09, 95% CI 1.01–1.18), with longer symptom duration, and with worsening UI symptoms (aOR 1.75, 95% CI 1.01–3.04). Women who saw physicians regularly, had more preventive women’s health visits, or both were more likely to seek UI treatment (aOR 1.18, 95% CI 1.07, 1.30). Race or ethnicity, socioeconomic measures, and education were not significantly related to seeking treatment for UI.

Conclusion

We found no evidence of racial or ethnic, socioeconomic or education level disparities in UI treatment–seeking. Rather, longitudinal UI characteristics were most strongly associated with treatment-seeking behavior in midlife women.

Introduction

Urinary incontinence (UI) is a frequent problem in mid-life and older women1. About 45% of mid-life women between the ages of 45–55 years report UI occurring at least a few times per month, and about 15% report daily UI2. UI can affect women’s lives negatively, leading to decreased quality of life3–6 and significant morbidity, such as functional decline7 and increased risk of falls and fractures in the elderly8.

Many effective treatments are available to women for any level of UI, including behavioral (e.g., limiting fluid intake, changing voiding habits), pelvic floor muscle exercises, pessaries, medications, and surgery9. In cross-sectional studies, less than half of women with UI tell health care providers about their problem10–13. These studies have identified factors associated with UI treatment-seeking, such as male gender11, greater social support14, and higher use of other health care services14.

Gaps in knowledge about disparities in UI treatment–seeking still exist. It is not known if changes in UI characteristics and physical, social, and psychological factors over time may affect whether women seek UI treatment. Even less clear is whether UI duration, changes in UI frequency and other factors associated with seeking treatment might differ between racial or ethnic, socioeconomic, educational backgrounds, or a combination of these. The present analyses explored potential disparities in UI treatment–seeking in a racial or ethnically diverse cohort of community-dwelling midlife women followed longitudinally over 9 years.

Materials and Methods

This is a secondary analysis of data from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) from 1996–2007. The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation is a multi-center, multi-racial or ethnic prospective cohort study investigating longitudinally the biological and psychosocial characteristics and common symptoms of midlife women across the menopausal transition. Briefly, from a sample of women recruited by random-digit-dialing and list-based sampling, each site of seven sites recruited approximately 450 women for Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation, consisting of about 50% white (non-Hispanic) women and 50% women from one designated minority racial or ethnic group. In this study, we included all women from six of the clinical sites (Pittsburgh, Oakland, Los Angeles, Detroit, Chicago, Boston) representing white (non-Hispanic), black, Chinese and Japanese women. We could not include the white (non-Hispanic) and Hispanic women from the New Jersey site as questionnaires were not administered there during the years of this investigation. Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation enrollment inclusion criteria included: age 42–52 years, self-identification as black; Japanese, Chinese, Hispanic or white, premenopausal or early perimenopausal status. Enrollment exclusion criteria included: inability to speak English, Japanese, or Cantonese; hysterectomy and/or bilateral oophorectomy, on any hormonal medications, or pregnant or lactating. The study protocol was approved by all institutional review boards, and participants provided written, informed consent.

Based on data from Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation questionnaires that were self-administered (6th grade reading level) at an approximately annual in-person visit, we created variables to describe UI characteristics as follows. We defined responses to the question “In the last month, about how many times have you leaked urine, even a small amount?” as daily for “almost daily or daily,” weekly for “several days per week,” monthly for “less than one day per week” and no clinically significant UI as “less than once per month” or none. We defined UI type by responses to the question “under what circumstances does leakage occur?” We defined women who reported leakage with “coughing, laughing, sneezing, jumping up and down, with physical activity” as having stress UI, while women who reported leakage with “when you have the urge to void and can’t reach the toilet fast enough” as having urge UI. We defined mixed UI when women responded positively to both circumstances of leakage. Finally, women who reported UI at any time point and then reported an increase in frequency from one annual visit to the next were considered to have worsening UI, i.e. from no regular UI to monthly or more, from monthly to weekly or more or from weekly to daily. We considered women who reported a decrease in frequency of UI from one annual visit to the next as having improving UI. In the same in-person visit self-administered questionnaire, participants reported on treatment-seeking behaviors for UI by responding yes or no to the following question that Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation included at baseline and in visits 7, 8 and 9: “Have you ever discussed your leakage with a doctor, nurse, or other health care professional?” after they had responded “yes” to a stem question: “Have you ever leaked urine, even a small amount?”

Covariates included self-reported race or ethnicity, income, and education level, level of difficulty in paying for basics, depressive15 and anxiety symptoms16, social support or network17, and experience of discrimination18, medical history and health care utilization. We calculated body mass index (weight/height2) based on measurements obtained by calibrated balance beam scale and by stadiometer. Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation defined menopause status using Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop (STRAW) criteria19. We created summary variables for the patterns of UI and these other variables as in prior publications2,20,21.

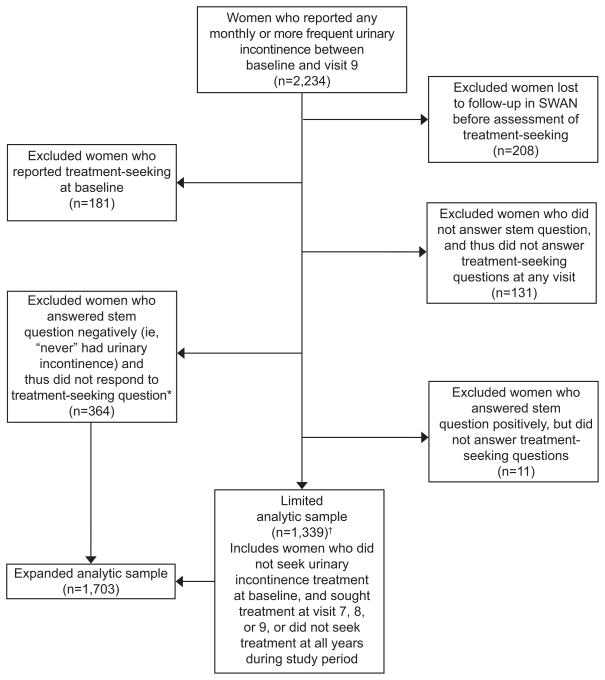

Women in our main analytic sample were those who remained in the study, reported UI at any visit, and responded to the treatment-seeking questions in visits 7, 8 or 9, or were presumed to have not sought treatment (Figure 1). We examined bivariate associations with seeking treatment using chi-squared tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables. We then used multiple logistic regression analysis, exploring forward, backward and stepwise methods to examine the associations between demographic, psychosocial, physical, health care, and UI characteristic variables and UI treatment–seeking across the first nine years of cohort observation. We chose our independent variables a priori based on the literature2,6,14 and from our bivariate analysis when p-values were ≤ 0.3. We selected our models based on best fit, defined as the lowest Aikaike Information Criterion (AIC)22.

Figure 1.

Study flowchart. *Expanded analytic sample includes the incontinent women who answered the treatment-seeking questions in visits 7, 8, or 9 and the 364 women who reported urinary incontinence in previous visits, but reported “never” having had urinary incontinence to stem questions in visits 7, 8, and 9, and thus did not respond to treatment-seeking questions. In our analyses of this expanded analytic sample, we presumed these 364 women did not seek treatment because at the time of those questions, they did not recall having reported urinary incontinence in the past. †Limited analytic sample includes 113 women who were censored in visits 7 and 8 for nonresponse after these years or loss to follow-up. SWAN, Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation.

We examined interactions in two ways. First, we developed stratified models using our primary independent variables: racial or ethnic category, socioeconomic status, and education. Second, we explored interaction between UI frequency and UI duration and each of these variables within our main model by entering these combinations as interaction terms.

Because women were questioned about UI treatment–seeking behaviors at baseline and then not until visit 7, we could not determine when during that 8-year interval women actually sought treatment and thus which factors preceded treatment-seeking behavior. To address this, we secondarily examined multivariable models in a subsample of women who had not reported seeking treatment before visit 7, following them through visit 9.

A subset of Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation–incontinent women had missing data because, although they reported UI one or more times prior to visit 7, they answered the stem question “Have you ever leaked urine, even a small amount” at visit 7, 8 and/or 9 negatively (N = 364), and thus did not respond to our treatment-seeking questions. To evaluate the potential bias this non-response could have on our results, we compared two sampling strategies. First, we counted the 364 women as missing and did not include them in what we defined as the limited analytic sample. Second, we assumed that these 364 incontinent women who responded negatively the stem question would not likely have sought treatment. For these women, we imputed “no UI treatment seeking” and included them in an expanded analytic sample, the primary results presented here. We compared the multivariable models for the limited and expanded analytic samples to examine the effect of our assumption.

Results

Of the 3302 women enrolled in the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation longitudinal cohort, 2234 (68%) reported monthly or more UI at any visit between baseline and year 9. Of these women who reported UI, a total of 1520 (68%) reported seeking UI treatment, most between baseline and year 9 (Figure 1). Compared to the 2251 women who remained in the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation through year 9, women who dropped out of the study or had missing data were more likely to be white with lower annual income and education at baseline, have a higher BMI, and either had no medical insurance or had public insurance. They were also more likely to report daily UI of urge or mixed type with a higher level of bothersomeness (data not shown).

The characteristics of incontinent women who did and did not seek UI treatment are shown in Table 1. Longitudinal characteristics of UI associated with seeking treatment in bivariate analyses were a longer duration of UI and more years reporting daily UI (Table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Incontinent Women, by Report of Seeking or Not Seeking Treatment for Urinary Incontinence in Visits 7, 8, and 9

| Sought Treatment (N = 525) | Did Not Seek Treatment (N = 1178) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number or Mean Percent (%) or Standard deviation (SD) | Number or Mean Percent (%) or Standard deviation (SD) | ||

| Race/ethnicity | <0.001 | ||

| White* | 282 (32.3) | 592 (67.7) | |

| Black | 173 (34.4%) | 330 (65.6) | |

| Asian | 70 (21.5) | 256 (78.5) | |

| Born in U.S. | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 448 (32.5) | 929 (67.5) | |

| No | 47 (19.7) | 192 (80.3) | |

| Difficulty paying for basics (baseline) | 0.09 | ||

| Not hard | 326 (29.4) | 783 (70.6) | |

| Somewhat hard | 153 (32.4) | 319 (67.6) | |

| Very hard | 45 (38.4) | 72 (61.5) | |

| Annual Household Income** | 0.12 | ||

| $35K and above | 374 (30.2) | 864 (69.8) | |

| Below $35K | 141 (33.9) | 275 (66.1) | |

| Education Level (baseline) | 0.82 | ||

| High School or Less | 93 (31.1) | 955 (69.0) | |

| Some college or greater | 430 (30.4) | 213 (69.6) | |

| Marital status (baseline) | 0.03 | ||

| Single | 74 (31.4) | 162 (68.6) | |

| Married or living as married | 328 (29.0) | 805 (71.1) | |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 116 (36.5) | 202 (63.5) | |

| BMI (mean at baseline) | 29.4 (7.8) | 27.8 (7.3) | < 0.001 |

| Parity | 0.06 | ||

| Nulliparous | 77 (26.2) | 217 (73.8) | |

| Parous | 447 (31.8) | 960 (68.2) | |

| Medical (baseline) | |||

| Diabetes | 27 (32.5) | 56 (67.5) | 0.71 |

| Hypertension | 129 (37.6) | 212 (62.2) | 0.001 |

| Medical insurance | 0.49 | ||

| Private | 474 (30.6) | 1074 (69.4) | |

| Public (Medicare, Medicaid, Military) | 27 (37.0) | 46 (63.0) | |

| None | 24 (29.3) | 58 (70.7) | |

| Baseline number of doctor’s visits (mean) | 4.3 (6.4) | 3.3 (5.0) | 0.001 |

| Baseline women health visits | < 0.001 | ||

| Visit in the last year | 407 (33.9) | 795 (66.1) | |

| Visit in the last 2 years | 75 (26.8) | 205 (73.2) | |

| Visit in the last 3+ years | 41 (19.6) | 168 (80.4) | |

| Depressive symptom score (0–60, mean) | 10.2 (9.4) | 10.2 (9.2) | 0.99 |

| Anxiety symptoms score (0–16, mean) | 2.7 (2.5) | 2.4 (2.2) | 0.02 |

| Importance of religion/spirituality | 0.04 | ||

| None | 43 (24.0) | 136 (76.0) | |

| A little | 143 (28.7) | 355 (71.3) | |

| A great deal | 339 (33.1) | 684 (66.9) | |

| Experience of discrimination | 0.002 | ||

| Sometimes/often any blatant | 156 (37.8) | 257 (62.2) | |

| Sometimes/often any subtle | 145 (29.3) | 350 (70.7) | |

| No significant mistreatment | 224 (28.2) | 571 (71.8) | |

| Reason for discrimination | < 0.001 | ||

| Race/ethnicity | 90 (35.9) | 161 (64.1) | |

| Gender | 26 (23.9) | 83 (76.2) | |

| Physical appearance | 43 (44.3) | 54 (55.7) | |

| Other reasons | 125 (33.4) | 249 (66.6) | |

| No reason given | 241 (27.7) | 630 (72.3) | |

| Number of people in household (mean) | 2.1 (1.6) | 2.3 (1.6) | 0.04 |

| SF-36ŧ physical score (0–100, mean) | 69.7 (38.2) | 76.5 (35.1) | <0.001 |

| SF-36ŧ vitality score (0–100, mean) | 53.9 (20.4) | 55.3 (19.7) | 0.18 |

| SF-36ŧ social function score (0–100, mean) | 78.2 (23.1) | 82.2 (20.3) | < 0.001 |

| SF-36ŧ emotional score (0–100, mean) | 74.5 (36.1) | 78.2 (34.1) | 0.05 |

| Age (years) at first report of UI | 0.002 | ||

| Less than 47 | 273 (34.6) | 515 (65.4) | |

| 47 or greater | 252 (27.5) | 663 (72.5) | |

| Menopausal status at first report of UI | < 0.001 | ||

| Pre- or Early peri-menopause | 482 (33.1) | 974 (66.9) | |

| Late peri- or Postmenopause | 21 (13.4) | 136 (86.6) | |

| Frequency of UI at first report | < 0.001 | ||

| Daily | 55 (58.5) | 39 (41.5) | |

| Weekly | 101 (43.2) | 133 (56.8) | |

| Monthly | 369 (26.8) | 1006 (73.2) | |

| Type of UI at first report | 0.001 | ||

| Stress | 250 (29.1) | 608 (70.9) | |

| Urge | 112 (29.2) | 272 (70.8) | |

| Mixed | 154 (39.1) | 240 (60.9) | |

| Bothersomeness of UI (0–10, mean)ŧŧ | 4.5 (2.8) | 3.2 (2.8) | < 0.001 |

All values are from baseline unless otherwise indicated. P-values are from chi-square test and t-test.

White refers to white, non-Hispanic,

Based on US median household income in 1995 of $33K

Short Form (36) Health Survey

Bothersomeness of UI was not asked in years 4,5,6, women whose first report of UI in 4,5,6 were excluded.

Missing data: For contiuous variables, N = 63. For categorical variables: N represented by numbers in table

Table 2.

Longitudinal Urinary Incontinence Characteristics of Incontinent Women by Report of Seeking or Not Seeking Treatment in Years 7, 8, and 9 in Extended Analytical Sample

| Sought Treatment (N=525) | Did Not Seek Treatment* (N =1178) | p-value§ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N or Mean Percent (%) or Standard deviation (SD) | N or Mean Percent (%) or Standard deviation (SD) | ||

| Duration of UI | < 0.001 | ||

| UI present at baseline | 373 (40.1) | 557 (59.9) | |

| Developed UI after baseline | 152 (19.7) | 621 (80.3) | |

| Mean person-years of UI frequency prior to seeking/not seeking treatment | |||

| Daily | 0.9 (1.7) | 0.3 (1.1) | < 0.001 |

| Weekly | 1.6 (1.8) | 1.0 (1.7) | < 0.001 |

| Monthly | 3.4 (2.3) | 4.3 (2.7) | < 0.001 |

| Frequency of UI in year prior to seeking/not seeking treatment | < 0.001 | ||

| Daily | 79 (65.3) | 42 (34.7) | |

| Weekly | 120 (46.9) | 136 (53.1) | |

| Monthly | 244 (31.9) | 522 (68.1) | |

| Change in frequency prior to seeking/not seeking treatment** | 0.13 | ||

| UI worsened | 228 (36.8) | 391 (63.2) | |

| UI unchanged with high variance | 195 (26.5) | 540 (73.5) | |

| UI unchanged with low variance | 25 (39.1) | 39 (60.9) | |

| UI improved | 77 (27.0) | 208 (73.0) | |

| Mean person-years of UI type prior to seeking/not seeking treatment | |||

| Stress only | 2.9 (2.9) | 3.6 (3.5) | < 0.001 |

| Urge only | 1.4 (2.3) | 1.8 (2.7) | 0.007 |

| Mixed | 2.5 (2.6) | 1.9 (2.6) | < 0.001 |

| Type of UI in year prior to seeking/not seeking treatment | < 0.001 | ||

| Stress only | 203 (27.6) | 533 (72.4) | |

| Urge only | 112 (27.9) | 289 (72.1) | |

| Mixed | 208 (38.0) | 340 (62.0) | |

| Change in UI type over years prior to seeking/not seeking treatment*** | 0.12 | ||

| Only stress | 79 (38.5) | 126 (61.5) | |

| Only urge | 25 (32.9) | 51 (67.1) | |

| Stress -> Mixed | 169 (26.0) | 482 (74.0) | |

| Urge -> Mixed | 87 (28.2) | 221 (71.8) | |

| Mixed or all other combinations | 163 (35.4) | 298 (64.6) | |

For women who did not report seeking treatment for UI through Year 9, calculations of mean person years are included through Year 9. Similarly, Year 8 values are used for frequency and type of UI in the “year prior” to not seeking treatment as Year 9 is the last documented time point for this observation.

Tests used for p-values are Chi-square test and t-test.

Change in UI was calculated as follows. Reports of an increase in UI frequency between categories were assigned a value of +1, reports of no change were assigned a 0, and reports of a decrease in UI frequency between categories was assigned a value of −1. These were summed to define: Worsening – overall score of >0 (N = 619) Improving – overall score of <0 (N = 285)

No change with high variance = 0, but with many changes in frequency over years of reporting UI (N = 735)

No change with low variance = 0, but with few changes in frequency over years of reporting UI (N = 64)

Definitions of change until each report of seeking treatment versus not seeking treatment.

Only stress at all visits prior (N = 205) Only urge at all visits prior (N = 76)

Stress -> Mixed – reports stress UI only at first or more visits, then reports both stress and urge (N = 651)

Urge -> Mixed – reports urge UI only at first or more visits, then reports both stress and urge (N = 308)

Mixed or other combinations – reports mixed at every visit, following none of above patterns (N = 461)

Missing data: N = 18

In multivariable analyses, women had higher odds of seeking treatment when they reported experiencing symptoms for more than 7 years, when UI worsened over time, when UI was at least daily and bothersome just before seeking treatment. Importantly, women who saw physicians regularly or had more visits for preventive women’s health care were also more likely to discuss their UI with a health care provider. When stratifying our models by race or ethnicity (Table 3), by level of difficulty paying for basics and by educations level (data not shown), we found few unique factors associated with seeking treatment. Likewise, in our primary multivariable models, interactions between UI frequency (p = 0.77) and duration (p = 0.94) and race or ethnicity as well as UI frequency (p = 0.60) and duration (p = 0.31) and difficulty paying for basics were not statistically significant. However, our power for detecting interactions between these variables, was low (0.40 with alpha = 0.05).

Table 3.

Adjusted Odds Ratios for Factors Associated with Seeking Treatment for Urinary Incontinence in Visits 7, 8, or 9

| All racial groups aOR (95% CI) |

White aOR (95% CI) |

Black aOR (95% CI) |

Asian aOR (95% C)) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race | ||||

| White* | Reference | |||

| Black | 1.25 (0.77, 2.04) | |||

| Asian | 0.74 (0.42, 1.33) | |||

| Difficulty paying for basics | ||||

| Not hard at all | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Somewhat hard | 1.29 (0.80, 2.08) | 1.14 (0.57, 2.28) | 1.77 (0.77, 4.07) | 0.88 (0.23, 3.36) |

| Very hard | 1.47 (0.61, 3.52) | 1.10 (0.26, 4.54) | 1.93 (0.56, 6.65) | 1.61 (0.08, 31.5) |

| Education Level (baseline) | ||||

| High School or Less | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Some college or greater | 1.07 (0.61, 1.87) | 0.90 (0.38, 2.16) | 1.17 (0.49, 2.80) | 1.42 (0.30, 6.73) |

| Parity | ||||

| Nulliparous | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Parous | 1.43 (0.80, 2.54) | 1.61 (0.79, 3.30) | 1.34 (0.37, 4.88) | 0.88 (0.19, 4.18) |

| Number of years with anxiety | 1.01 (0.92, 1.10) | 1.07 (0.79, 1.22) | 0.96 (0.82, 1.12) | 0.96 (0.75, 1.24) |

| SF-36 vitality score | 1.01 (1.00, 1.02) | 1.02 (1.01, 1.03) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.03) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.02) |

| Number women’s health visits | 1.18 (1.07, 1.30) | 1.20 (1.04, 1.38) | 1.12 (0.94, 1.34) | 1.30 (0.99, 1.72) |

| Average number MD visits | 1.07 (1.02, 1.12) | 1.07 (1.00, 1.14) | 1.09 (0.99, 1.20) | 1.04 (0.92, 1.18) |

| Diabetes | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 0.63 (0.24, 1.64) | 0.94 (0.18, 5.03) | 0.51 (0.13, 1.99) | 0.58 (0.05, 7.02) |

| Frequency of UI at first report | ||||

| Monthly | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Weekly | 1.71 (0.91, 3.19) | 1.85 (0.75, 4.55) | 1.22 (0.40, 3.67) | 2.26 (0.45, 11.4) |

| Daily | 2.38 (0.89, 6.36) | 3.43 (0.79, 14.8) | 1.50 (0.31, 7.15) | 3.49 (0.21, 57.30) |

| Frequency of UI in year prior to report | ||||

| None | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Monthly | 1.75 (0.98, 3.15) | 1.66 (0.67, 4.12) | 1.75 (0.67, 4.56) | 2.08 (0.47, 9.24) |

| Weekly | 2.17 (0.99, 4.76) | 2.20 (0.67, 7.24) | 1.93 (0.54, 6.94) | 2.89 (0.32, 26.4) |

| Daily | 3.16 (1.15, 8.67 | 3.67 (0.83, 16.3) | 2.57(0.51, 12.90) | 1.66 (0.05, 52.20) |

| Duration of UI | ||||

| Present at baseline (> 7 yrs) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Less than 4 years | 0.41 (0.15, 1.08) | 0.39 (0.10, 1.53) | 0.50 (0.10, 2.53) | 0.15 (0.01, 6.72) |

| 4–7 years | 0.37 (0.21, 0.65) | 0.31 (0.13, 0.72) | 0.38 (0.15, 1.01) | 0.58 (0.13, 2.64) |

| UI improve in year prior | 0.62 (0.32, 1.19) | 0.54 (0.22, 1.35) | 0.85 (0.26, 2.83) | 0.51 (0.10, 2.64) |

| UI worse in year prior | 1.75 (1.01, 3.04) | 1.90 (0.87, 4.13) | 1.94 (0.75, 4.99) | 1.19 (0.26, 5.56) |

| Bothersomeness of UI | 1.09 (1.01, 1.18) | 1.10 (0.98, 1.23) | 1.12 (0.98, 1.29) | 1.05 (0.85, 1.28) |

White refers to white, non-Hispanic, aOR = adjusted Odds Ratio, CI = Confidence Interval

CIs in this model represent correction for 78 comparisons: alpha = 0.05/78 or p = 0.0064

Bolded values represent those results that are statistically significant

All values from baseline unless otherwise indicated. All variables in model are represented in the table.

Independent variables selected by stepwise selection using 0.3 as entry criteria and 0.2 as stay criteria.

For our secondary analysis of incontinent women who had not sought treatment for their UI before year 7, overall, about 12% reported seeking UI treatment between visits 7 and 9 (about 6% per year). As with our primary analysis, we found that frequency of UI in the year prior to seeking treatment and longer duration of UI had the strongest association with UI treatment–seeking. Among this smaller subset of women, we found no differences in the rates of seeking treatment by racial or ethnic group (data not shown).

The 364 incontinent women who did not answer the treatment-seeking questions because they answered “no” to the stem question “Have you ever leaked urine, even a small amount?” and for whom we imputed “no treatment seeking” in our expanded analytic sample differed from those for whom we had complete data. They were more likely to be black or Asian, not born in the US, and have a lower education level and annual household income. More than 50% of these 364 women had reported UI at least twice during the previous years; however, they were less likely to report daily UI, less likely to report mixed UI symptoms, and had a lower level of UI bothersomeness. When we compared our multivariable models of the expanded analytic sample to those in the limited analytic sample, we found few differences. Black women were statistically more likely than white women to seek treatment in our limited analytic sample (OR 1.59, 95% CI 1.18, 2.16), than in our expanded sample (aOR 1.25, 95% CI 0.77, 2.04). Frequent UI in the year prior to seeking treatment was strongly associated with seeking treatment in our expanded analytic sample, but not in our limited analytic sample. Otherwise, point estimates for all other variables were similar.

Discussion

In this 9-year, longitudinal study of midlife women, we found no clear or consistent evidence of racial, educational or socioeconomic disparities in seeking treatment for UI. Rather, longitudinal characteristics of UI had the strongest association with UI treatment-seeking behavior. In cross-sectional studies, women with more frequent and bothersome UI symptoms were more likely to seek care 14,23,24. Over time, we found that worsening symptoms, longer duration of symptoms, and persistent symptoms of daily UI were associated with women seeking UI treatment.

We found that women with more health care contact were more likely to report seeking treatment for their UI14. Women who seek care for other health concerns may be more likely to seek care for UI, or more health care visits may provide more opportunity to discuss UI. Higher health care use may also represent a closer doctor–patient relationship. Of particular importance to gynecologists, the results of our study suggest that regular women’s preventive health visits have the benefit of increasing the opportunity for incontinent women to discuss their UI.

Our study results do not support previous findings that black women or women with lower socioeconomic circumstances are either less likely to seek care or seek care only at a higher level of bother or UI frequency than white women or women of higher socioeconomic resources25. Some of the intriguing findings in our bivariate analyses, such as experience of discrimination, higher importance of spirituality, anxiety symptoms, and greater social support, which may be related to race or ethnicity, socioeconomic status, or education level did not persist after adjustment in multivariable models but warrant further investigation.

The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation has collected a rich variety data that allowed a multi-layered exploration of changes in UI characteristics and UI treatment–seeking in a diverse community-based sample of women over 9 years. However, our study had some important limitations. While our UI questions were very similar to those in validated questionnaires 26,27, such instruments were not available at the initiation of the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Women with UI were more likely to drop out of our study. Race or ethnicity, income and education play a role in longitudinal cohort retention; white women with lower income and education were more likely to drop out of the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. These factors may also have affected questionnaire responses as more black, Asian, and immigrant women with lower incomes and education did not respond to our treatment-seeking questions due to inconsistent UI reporting. Hispanic women could not be included in this analysis. The women who participated in the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation over 9 years represent those who actively engage in regular study visits and thus may be more likely to engage the medical system. Only 5% of our cohort reported not having health insurance, half the national average for this age group and time frame28 and thus our cohort had ready access to care. For all these reasons, our study participants were probably more likely to seek care than the general population. Some of our analyses were limited by small numbers. For some of our analyses, we did not know exactly when in the intervening period between baseline and visit 7 a woman sought UI treatment; patterns of UI (such as worsening or no change in UI) may have crossed over the point of UI treatment seeking, rather than clearly preceded it. However, our analysis of longitudinal UI characteristics in women who sought care for the first time after visit 7 yielded similar results, suggesting minimal effect of this uncertainty.

The results of our investigation are important for research, public health outreach, and the clinical care of women. Our findings demonstrate some important problems in UI epidemiologic research. We demonstrated higher rates of inconsistent UI reporting among black, Asian and immigrant women on our questionnaires, suggesting differences in either meaning given to their UI problem or problems in interpretation of the questionnaire. Consideration should be given to developing instruments for assessing and validating change in UI over time in diverse populations. For public health educators, messages that encourage women to seek care for worsening or a longer duration of UI may be important for encouraging women to seek care. Clinicians should be more vigilant questioning infrequent health care system users about this common condition that may be affecting quality of life. While women may not report their UI problem at its onset, clinicians can use preventive women’s health visits to educate patients about returning for worsening of UI symptoms, thus establishing a relationship that encourages seeking treatment for UI at future health care visits.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial Support and Acknowledgements

Supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) and NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health (ORWH) Grant: DK092864. The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) has grant support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), DHHS, through the National Institute on Aging (NIA), the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) and the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health (ORWH) (Grants U01NR004061; U01AG012505, U01AG012535, U01AG012531, U01AG012539, U01AG012546, U01AG012553, U01AG012554, U01AG012495).

The authors thank the study staff at each site and all the women who participated in SWAN.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIA, NINR, ORWH or the NIH.

References

- 1.Hannestad YS, et al. A community-based epidemiological survey of female urinary incontinence: the Norwegian EPINCONT study. Epidemiology of Incontinence in the County of Nord-Trondelag. J of Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:1150–1157. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00232-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waetjen LE, et al. Factors associated with prevalent and incident urinary incontinence in a cohort of midlife women: a longitudinal analysis of data: study of women’s health across the nation. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:309–318. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Botlero R, Bell RJ, Urquhart DM, Davis SR. Urinary incontinence is associated with lower psychological general well-being in community-dwelling women. Menopause. 2010;17:332–337. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181ba571a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Margareta N, Ann L, Othon L. The impact of female urinary incontinence and urgency on quality of life and partner relationship. Neurourol Urodyn. 2010;28:976–981. doi: 10.1002/nau.20709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salvatore S, et al. The impact of urinary stress incontinence in young and middle-age women practising recreational sports activity: an epidemiological study. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43:1115–1118. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2008.049072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Minassian VA, et al. Predictors of care seeking in women with urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn. 2012;31:470–474. doi: 10.1002/nau.22235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Omli R, et al. Urinary incontinence and risk of functional decline in older women: data from the Norwegian HUNT-study. BMC geriatrics. 2013;13:47. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-13-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown JS, et al. Urinary incontinence: does it increase risk for falls and fractures? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:721–725. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb04744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abrams P, et al. Fourth International Consultation on Incontinence Recommendations of the International Scientific Committee: Evaluation and treatment of urinary incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse, and fecal incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn. 29:213–240. doi: 10.1002/nau.20870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shaw C. A review of the psychosocial predictors of help-seeking behaviour and impact on quality of life in people with urinary incontinence. J Clin Nurs. 2001;10:15–24. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2001.00443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roberts RO, et al. Urinary incontinence in a community-based cohort: prevalence and healthcare-seeking. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:467–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb02468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hagglund D, et al. Quality of life and seeking help in women with urinary incontinence. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001;80:1051–1055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seim A, et al. Female urinary incontinence--consultation behaviour and patient experiences: an epidemiological survey in a Norwegian community. Fam Pract. 1995;12:18–21. doi: 10.1093/fampra/12.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burgio K, et al. Treatment seeking for urinary incontinence in older adults. J Amn Geriatr Soc. 1994;42:208–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1994.tb04954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Radloff L. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–283. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gold EB, et al. Longitudinal analysis of the association between vasomotor symptoms and race/ethnicity across the menopausal transition: study of women’s health across the nation. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1226–1235. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32:705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams DSM, Jackson JS. Race, social identity, and physical health: Interdisciplinary explorations. Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soules MR, et al. Executive summary: Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop (STRAW) Fertil Steril. 2001;76:874–878. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)02909-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Waetjen LE, et al. Factors associated with worsening and improving urinary incontinence across the menopausal transition. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:667–677. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31816386ce. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waetjen LE, et al. Association between Menopausal Transition Stages and Developing Urinary Incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 2009 doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181bb531a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akaike H. Information measures and model selection. Int Stat Inst. 1983;22:277–291. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fultz NH, Herzog AR. Self-reported social and emotional impact of urinary incontinence. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:892–899. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sampselle CM, et al. Urinary incontinence predictors and life impact in ethnically diverse perimenopausal women. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:1230–1238. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02241-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berger MB, et al. Racial differences in self-reported healthcare seeking and treatment for urinary incontinence in community-dwelling women from the EPI study. Neurourol Urodyn. 30:1442–1447. doi: 10.1002/nau.21145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown JS, et al. The sensitivity and specificity of a simple test to distinguish between urge and stress urinary incontinence. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:715–723. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-10-200605160-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lukacz ES, et al. Epidemiology of prolapse and incontinence questionnaire: validation of a new epidemiologic survey. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2005;16:272–284. doi: 10.1007/s00192-005-1314-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States 2010. 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.