Abstract

Background and Objectives

Impulsive, maladaptive, and potentially self-damaging behaviors are a hallmark feature of borderline personality (BP) pathology. Difficulties with emotion regulation have been implicated in both BP pathology and maladaptive behaviors. One facet of emotion regulation that may be particularly important in the relation between BP pathology and urges for maladaptive behaviors is emotion differentiation.

Methods

Over one day, 84 participants high (n = 34) and low (n = 50) in BP pathology responded to questions regarding state emotions and urges to engage in maladaptive behaviors using handheld computers, in addition to a measure of emotion-related difficulties controlling impulsive behaviors.

Results

Results revealed that individuals high in BP pathology reported greater emotion-related impulsivity as well as daily urges to engage in maladaptive behaviors. However, the association between BP group and both baseline emotion-related impulsivity and daily urges for maladaptive behaviors was strongest among individuals who had low levels of positive emotion differentiation. Conversely, negative emotion differentiation did not significantly moderate the relationships between BP group and either emotion-related difficulties controlling impulsive behaviors or state urges for maladaptive behaviors.

Limitations

Limitations to the present study include the reliance upon an analogue sample and the relatively brief monitoring period.

Conclusions

Despite limitations, these results suggest that, among individuals with high BP pathology, the ability to differentiate between positive emotions may be a particularly important target in the reduction of maladaptive behaviors.

Keywords: Emotions, borderline personality disorder, emotion regulation, maladaptive behaviors

Introduction

Features of borderline personality disorder (BPD) include affective instability, identity disturbance, disruptions within relationships, and impulsive, self-destructive behaviors (American Psychiatric Association [APA] 2013). Indeed, borderline personality (BP) pathology is associated with a range of maladaptive behaviors, including substance misuse (Trull, Sher, Minks-Brown, Durbin, and Burr 2000), non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI; Muehlenkamp, Ertelt, Miller, and Claes 2011), binge eating (Sansone, Levitt, and Sansone, 2005), and risky sexual behavior (Tull, Gratz, and Weiss 2011). In the context of BPD, these behaviors have largely been viewed as means to avoid or escape aversive emotional states (Linehan, 1993). Given that emotion regulation deficits are considered central to BPD (Linehan 1993) and risky behaviors (Weiss, Tull, Viana, Anestis, and Gratz 2012), further examination of the role of various aspects of emotion regulation in maladaptive behaviors among individuals with BP pathology is warranted.

Emotion regulation difficulties encompass maladaptive ways of responding to emotions, including lack of emotional awareness or acceptance, limited access to effective emotion modulation strategies, behavioral dyscontrol in the face of emotional distress, and lack of emotional clarity (Gratz and Roemer 2004). Existing research (e.g., Chapman, Leung, and Lynch 2008; Salsman and Linehan 2012) and theory (e.g., Linehan 1993) provide support for a robust association between BP pathology and difficulties regulating emotions. Importantly, emotion regulation deficits may play an important role in driving maladaptive behaviors among persons with BP pathology. For example, findings have demonstrated that other disorders linked to maladaptive behaviors (e.g., substance abuse [e.g., Fox, Hong, and Sinha 2008]; pathological gambling [Williams, Grisham, Erskine, and Cassedy 2012]) are positively associated with emotion regulation difficulties. Furthermore, difficulties in emotion regulation has been shown to be a significant predictor of NSSI (Gratz and Tull 2010), risky sexual behavior (Tull, Weiss, Adams, and Gratz 2012), and binge eating (Whiteside, Chen, Neighbors, Hunter, Lo, and Larimer 2007) above and beyond other relevant risk factors. Persons with BPD are particularly prone to engage in these types of maladaptive behaviors that have been linked to emotion regulation deficits more broadly. More directly, a study of individuals high and low in BP pathology yielded the unexpected finding that observing emotions, in comparison with emotional suppression, resulted in greater urges to engage in maladaptive behaviors in daily life among participants high in BP pathology (Chapman, Rosenthal, and Leung 2009), in line with increasing research that suggests suppression may have some benefits (at least in the short term; Dunn et al., 2009). Conversely, awareness of emotions may elicit distress, if not used in conjunction with other skills (e.g., nonjudgmental stance; Baer et al. 2008; Peters, Eisenlohr-Moul, Upton, & Baer in press). Taken together, this body of research supports a link between maladaptive behaviors and emotion regulation difficulties in persons with BP features.

Focusing on specific domains of emotion regulation difficulties, evidence suggests that individuals with BPD may struggle with emotion differentiation, or the ability to distinguish between distinct emotions of similar valence (Barrett, Gross, Christensen, and Benvenuto 2001), instead reporting (and possibly experiencing) their emotional experiences in broader, non-specific terms (e.g., as good or bad). Indeed, BP pathology is associated with a lack of emotional clarity (Salsman and Linehan 2012), lower emotional awareness (Leible and Snell 2004), and difficulties identifying and labeling specific emotions (Modestin, Furrer, and Malti 2004; Wolff, Stiglmayr, Bretz, Lammers, and Auckenthaler 2007). Preliminary evidence suggests that, when describing their emotional experiences, individuals with BPD emphasize valence (i.e., whether an emotion is pleasant or unpleasant) over arousal (whether an emotion is more calm or low in arousal, vs. highly arousing) (Suvak et al. 2011). Furthermore, research suggests that individuals with BPD demonstrate poorer negative emotion differentiation in their everyday lives, relative to controls (Zaki, Coifman, Rafaeli, Berenson, and Downey 2013). Collectively, these studies underscore the relevance of emotion differentiation to BP pathology. Further examination of the possible consequences of poor emotion differentiation with respect to maladaptive behaviors (and urges to engage in them) is needed, in order for us to better understand the practical importance of this emotion regulation deficit in BPD.

The ability to differentiate among distinct, similarly-valenced emotions may confer resiliency, buffering individuals from maladaptive behaviors and other negative outcomes. For instance, the ability to distinguish between positive emotions has been shown to predict less avoidant or impulsive coping in response to stress (Tugade, Fredrickson, and Barrett 2004). Furthermore, in a study of social drinkers, among those with intense negative emotions, higher levels of emotion differentiation in daily life predicted less alcohol consumption (Kashdan, Ferssizidis, Collins, and Muraven 2010). To date, however, only one study has examined the association between emotion differentiation and maladaptive behaviors in the context of BP pathology. Zaki and colleagues (2013) found that, controlling for rumination, negative emotion differentiation predicted less NSSI within a sample of participants with BPD. Although the mechanisms by which emotion differentiation may confer resiliency are not well-understood, research and theory suggest that a lack of emotional clarity may heighten distress (Linehan, 1993), whereas labeling emotions may decrease emotional arousal (Lieberman et al. 2007). As such, it is possible that undifferentiated emotions may heighten emotional arousal, setting the stage for more impulsive behaviors that function to regulate such intense emotions. Despite the clear clinical implications of this line of research, extant studies have not examined the moderating role of emotion differentiation in the relationship of BP features with other forms of maladaptive behaviors. Furthermore, to our knowledge, no studies have examined the association of positive emotion differentiation with maladaptive behaviors in the context of BP pathology. In light of emerging research underscoring the importance of positive affect on impulsivity (e.g., Veilleux et al. 2013), consideration of both positive and negative emotion differentiation in the context of maladaptive behaviors is warranted.

The primary aim of the present study was to extend existing research by examining the roles of positive and negative emotion differentiation in daily life in predicting emotion-related difficulties controlling impulsive behaviors and urges for a range of maladaptive behaviors among individuals high and low levels in BP pathology. Based on past research (Kashdan et al. 2010; Tugade et al. 2004), we hypothesized that emotion differentiation would moderate the relationship between BP features and difficulties controlling maladaptive behaviors and urges for maladaptive behaviors. Specifically, we expected that the high-BP group would endorse greater emotion-related difficulties controlling impulsive behaviors and higher urges for maladaptive behaviors at low levels of emotion differentiation.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Participants were university students recruited from a larger sample (N = 275) based on their scores on the Personality Assessment Inventory-Borderline Features Scale (PAI-BOR; Morey, 1991). Following Trull (2001), individuals who scored greater than or equal to 38 on the PAI-BOR were designated “high-BP.” This cutoff has high positive predictive power (0.97) with respect to SCID-II diagnoses of BPD, indicating that this is an appropriate method of delineating individuals for the high-BP group (Jacobo, Blais, Baity, and Harley 2007). Individuals who scored below 23 (the mean score among undergraduates; Morey, 1991) on the PAI-BOR were designated “low-BP.” Of the eligible participants (n = 116), 28 declined to participate, and 4 did not complete the procedures, resulting in a final sample of 34 high-BP and 50 low-BP participants (mean age = 21.15, SD = 3.01). Consistent with the demographics of undergraduate psychology courses at the university, the majority of the participants were female (81%) and either East Asian Canadian (50.00%) or White/Caucasian (32.14%).

Procedures

This study received approval by the university’s Research Ethics Board. After providing written informed consent, participants completed a set of questionnaires, including the PAI-BOR. Participants were provided with a Personal Digital Assistant (PDA: PalmTM Zire 22), programmed using the Purdue Momentary Assessment Tool (PMAT; Weiss, Beal, Lucy, and MacDermid 2004). The PDAs beeped eight times per day on a pseudorandomized schedule (constrained by inter-beep intervals 60-90 min) over 12 hours (based on the participants’ start and end times). These data were collected as part of a larger study examining the effects of emotion regulation strategies on urges for maladaptive behaviors over 4 days (see Author, Year). For the purposes of the present study, we restricted our examination to the day during which participants received instructions to respond to their emotions normally (whereas in the remainder of the study, participants were instructed to use specific strategies to regulate their emotions; see Author, Year). Participants were paid $40 for their time.

Measures

Borderline personality pathology

As described above, the PAI-BOR (Morey, 1991) was used to designate high and low levels of BP features. The PAI-BOR contains 24 items, rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale, which assess four domains of BP features (affective instability, identity problems, negative relationships, and self-harm). In the present study, the PAI-BOR demonstrated good internal consistency (α = 0.88).

Emotion-related difficulties controlling impulsive behaviors

One dimension of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS; Gratz and Roemer, 2004) was used to assess difficulties controlling impulsive behaviors when distressed (DERS IMPULSE). The DERS IMPULSE subscale consists of 6 items (range 5-30), including items such as “When I’m upset, I lose control over my behaviors.” Participants rate the extent to which each item applies to them on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = almost never, 5 = almost always). Items were recoded and summed such that higher scores indicated greater difficulties controlling impulsive behaviors when distressed. While extant research highlights the multi-faceted nature of impulsivity (Cyders, Smith, Spillane, Fischer, Annus, and Peterson 2007; Whiteside, Lynam, Miller, and Reynolds 2005), a growing body of literature indicates that emotion-based dispositions to engage in rash action, such as urgency (a construct that theoretically and empirically overlaps with DERS IMPULSE; Cyders and Smith 2007, 2008; Gratz and Roemer 2004), predict a range of risky behaviors above and beyond other impulsivity domains (see Cyders and Smith, 2007, 2008 for a review). The DERS has been found to have high internal consistency (α = 0.93), good test–retest reliability over a period ranging from 4 to 8 weeks (ρI = 0.88, p < 0.01), and adequate construct and predictive validity (Gratz and Roemer, 2004). Internal consistency in the current study was good (α = 0.88).

Potential covariates

We assessed overall affect intensity using the total score from the Affect Intensity Measure (AIM; Larsen and Diener 1984), which demonstrated good internal consistency in the present study (α = 0.90). In addition, we administered the Brief Symptom Inventory (Derogatis 1994), a 53-item self-report measure which yields the global severity index, a weighted score that takes into account the number of symptoms endorsed, as well as the intensity of the associated distress. This measure demonstrated high internal consistency in the present study (α = .97).

Question sets administered by PDA

Emotion differentiation

Following each beep on the PDA, participants completed the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson, Clark, and Tellegen 1988). The PANAS is a well-validate measure of emotional state, and contains 10 positive and 10 negative positive affect adjectives, each rated on a 5-point Likert scale, where higher scores reflect greater intensity. In addition to rating the items on the PANAS, participants were also instructed to rate intensity of “sad.” To measure emotion differentiation, consistent with past research (e.g., Kashdan et al. 2010; Tugade et al. 2004; similar methods also used by Barrett et al. 2001; Zaki et al. 2013), we calculated the average intraclass correlations with absolute agreement across ratings (on a 5-point Likert scale) of the eleven negative affect adjectives (ten negative affect adjectives from the PANAS and “sad”) and ten positive affect adjectives (from the PANAS), resulting in negative and positive emotion differentiation indices. These correlations were normalized (to z scores) and reversed such that larger correlations indicate a greater ability to discriminate across different emotions, whereas smaller correlations indicate that different emotions were rated similarly, suggestive of lower emotion differentiation. Using similar methods, Barrett and colleagues (2001) found that emotion differentiation was associated with use of adaptive emotion regulation strategies.

State urges to engage in maladaptive behaviors

Following each beep on the PDA, participants rated how strong their urges were to engage in twelve maladaptive behaviors on a scale from 1 “not at all or very slightly” to 5 “extremely”(Chapman et al. 2009). These items map onto the behaviors described in the impulsive criterion for BPD (APA 2013), with the addition of “self-injury” and “escape your emotions.” Items included the following: binge eat (eating much more than a regular meal); purge (vomiting, exercise, laxatives); use drugs; use alcohol; harm yourself/self-injury (e.g., cut, burn, hit self, or other self-injury); yell/scream; hit someone/throw things; drive recklessly; spend money you don’t have or gamble; engage in unprotected/risky sexual activity; get away from your emotions by going to sleep; and escape your emotions. Consistent with past research using this measure, (Chapman et al. 2009), urges were summed, and internal consistency was good (α = 0.96).

Data Analytic Plan

First, preliminary analyses were conducted to examine descriptive statistics and ensure variables fell within the acceptable range of normality (skew < 2.0, kurtosis < 7.0; Curran, West, and Finch 1996). We examined the zero-order associations between demographic (i.e., age, race/ethnicity [dichotomized to represent minority vs. White], and sex) and other relevant potential covariates (i.e., number of beeps on the PDA completed, affective intensity and general psychopathology) and the dependent variables to determine which covariates to include in the primary analyses.

To examine the question of whether emotion differentiation would moderate the association between BP group and impulses for maladaptive behaviors, we conducted a series of hierarchical multiple regression analyses. Specifically, we conducted separate analyses for each dependent variable (difficulties in impulse control when distressed [DERS IMPULSE] and state urges for maladaptive behaviors). For each dependent variable, we examined two models: (1) positive emotion differentiation as a moderator, and (2) negative emotion differentiation as a moderator. In each of these models, relevant covariates were entered in the first step, BP group and emotion differentiation were entered in the second step, and the interaction of BP group and emotion differentiation were entered in the final step. Any significant interactions were explored following the methods described by Aiken and West (1991). Regressions lines were plotted by BP group and one standard deviation above and below mean levels of emotion differentiation, following which follow-up tests were conducted to test whether the slopes of the regression lines differed significantly from zero.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

All variables of interest fell within the acceptable range of normality, with the exceptions of age and positive emotion differentiation, which were log (base 10) transformed, in accordance with recommendations (Tabachnick and Fidell 2000). On average, participants responded to 6.32 (SD = 1.40; range = 2-8) of the 8 beeps on the PDA, and there were no significant differences between the high-BP and low-BP groups in terms of number of missed beeps (t (82) 1.28, p = 0.20). The high-BP and low-BP groups were comparable in terms of age (t (82) = 1.36, p = 0.18), sex (χ2 (1) = 0.29, p = 0.59), and racial/ethnic composition (χ2 (1) = 1.94, p = 0.16). In terms of potential covariates, there were no significant associations (rs < 0.16, ps > 0.17) between the dependent variables and demographic variables or number of beeps completed on the PDA, with one exception: DERS IMPULSE was associated with non-White ethnicity (r = 0.22, p = 0.047). Furthermore, general psychopathology and affective intensity were associated with DERS-IMPULSE and state urges for maladaptive behaviors (rs = 0.32 - 0.77, ps < 0.01). As such, analyses were conducted with these covariates. Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations between variables of interest are available in Table 1.

Table 1.

Intercorrelations, means, and standard deviations of primary variables of interest.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Affect intensity | - | 0.42*** | -0.07 | -0.15 | 0.41*** | 0.32** |

| 2. General psychopathology | - | - | -0.09 | -0.09 | 0.77*** | 0.59*** |

| 3. Negative emotion differentiationa | - | - | - | 0.21 | -0.22 | -0.08 |

| 4. Positive emotion differentiationa | - | - | - | - | -0.20 | -.14 |

| 5. DERS-IMPULSE | - | - | - | - | - | 0.56*** |

| 6. Total daily urges | - | - | - | - | - | - |

|

| ||||||

| Mean (SD) low BP group | 143.04 (18.76) |

0.58 (0.35) |

0.16 (1.06) |

0.13 (1.20) |

8.75 (2.03) |

1.09 (0.13) |

| Mean (SD) high BP group | 164.01 (18.23) |

1.75 (0.64) |

-0.19 (0.90) |

-0.18 (0.57) |

17.16 (5.11) |

1.50 (0.36) |

| Test statistic t | 5.09*** | 9.76*** | 1.57 | 1.60 | 9.12*** | 6.33*** |

Note. DERS-IMPULSE = impulsive behavior when distressed scale of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale assessed at baseline; BP = borderline personality.

Means displayed are transformed.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Primary Analyses

Emotion-related difficulties controlling impulsive behaviors

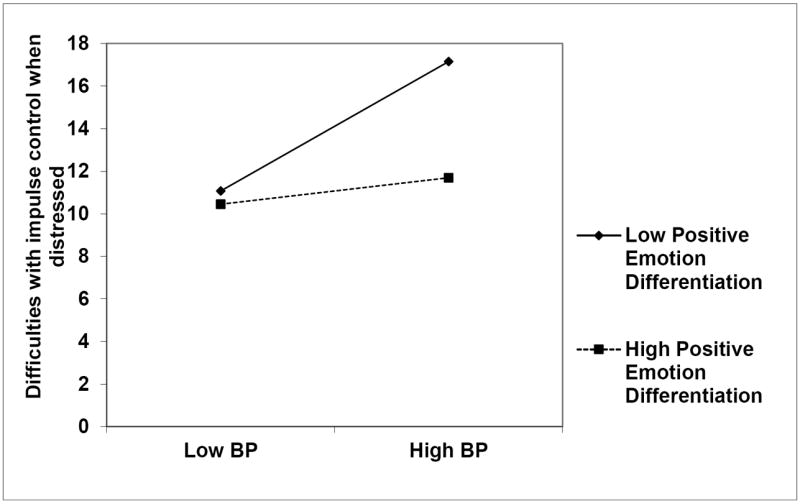

The hierarchical regression analysis examining the main and interactive effects of BP and positive emotion differentiation on DERS-IMPULSE was significant, R2 = 0.70, p < 0.001 (see Table 2). In the final step of the model, BP group, β = 0.33, p = 0.002, and the BP × positive emotion differentiation interaction, β = -0.16, p = 0.02, emerged as significant predictors, whereas positive emotion differentiation did not, β = -0.06, p = 0.42. The addition of the BP × positive emotion differentiation interaction significantly improved the model, ΔR2 = 0.02, p = 0.02. Tests of the slopes of the regression lines (see Figure 1) revealed that the relationship between BP group and DERS-IMPULSE increased in magnitude as positive emotion differentiation moved from high (b = 1.25, SE = 1.70, t = 0.73, p = 0.47) to low (b = 6.07, SE = 1.40, t = 4.34, p < 0.001).1

Table 2.

Hierarchical regression analyses exploring the roles of borderline personality group, emotion differentiation, and their interaction in difficulties controlling impulses when distressed.

| Variables | β | R2 (Adj. R2) | ΔR2 | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Positive Emotion Differentiation | ||||

| Step 1 | 0.61 (0.59) | 41.83*** | ||

| Race/ethnicity (0 = non-White) | -0.05 | |||

| General psychopathology | 0.72*** | |||

| Affective intensity | 0.11 | |||

| Step 2 | 0.68 (0.66) | 0.07*** | 32.96*** | |

| BP group (0 = low BP) | 0.38** | |||

| Positive emotion differentiation | -0.12 | |||

| Step 3 | 0.70 (0.68) | 0.02* | 29.91*** | |

| BP × positive emotion differentiation | -0.16* | |||

| Model 2: Negative Emotion Differentiation | ||||

| Step 1 | 0.59 (0.58) | 35.96*** | ||

| Race/ethnicity (0 = non-White) | -0.06 | |||

| General psychopathology | 0.71*** | |||

| Affective intensity | 0.09 | |||

| Step 2 | 0.67 (0.64) | 0.07** | 28.54*** | |

| BP group (0 = low BP) | 0.36*** | |||

| Negative emotion differentiation | -0.12 | |||

| Step 3 | 0.67 (0.64) | 0.002 | 23.63*** | |

| BP × negative emotion differentiation | -0.05 | |||

Note. BP = borderline personality.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Fig. 1.

Interactive effect of borderline personality (BP) group and positive emotion differentiation on difficulties controlling impulses when under distress.

The hierarchical regression analysis examining the main and interactive effects of BP and negative emotion differentiation on DERS-IMPULSE was significant, R2 = 0.67, p < 0.001 (see Table 1). BP group emerged as a significant predictor, β = 0.35, p = 0.003, whereas negative emotion differentiation did not, β = -0.09, p = 0.32. The addition of the BP × negative emotion differentiation interaction did not significantly improve the model, ΔR2 = 0.002, p = 0.55.

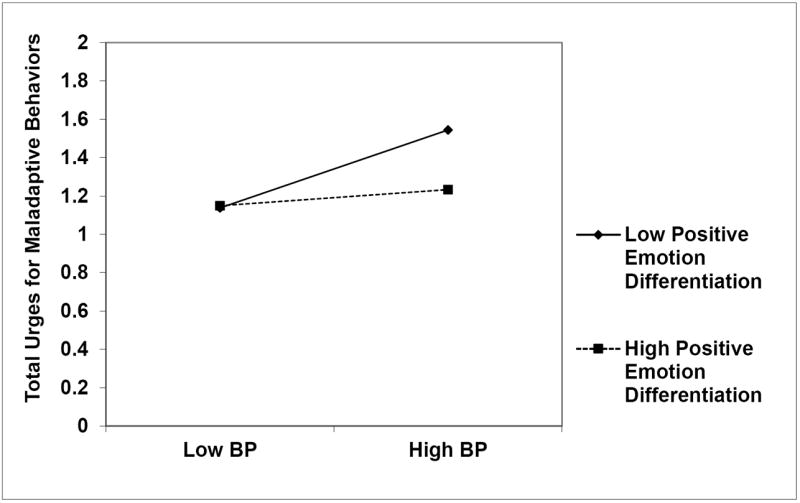

State urges to engage in maladaptive behaviors

The hierarchical regression analysis examining the main and interactive effects of BP and positive emotion differentiation on state urges was significant, R2 = 0.45, p < 0.001 (see Table 3). BP group emerged as a significant predictor, β = 0.38, p = 0.01, whereas positive emotion differentiation did not, β = -0.02, p = 0.84. The addition of the BP × positive emotion differentiation interaction significantly improved the model, β = -0.19, ΔR2 = 0.03, p = 0.049. Tests of the slopes of the regression lines (see Figure 2) revealed that the relationship between BP group and state urges for maladaptive behaviors increased in magnitude as positive emotion differentiation moved from high (b = 0.08, SE = 0.13, t = 0.64, p = 0.42) to low (b = 0.41, SE = 0.11, t = 3.72, p < 0.001).2 In supplementary analyses, we examined the main and interactive effects of BP and positive emotion differentiation on the 12 urges in separate regression models. The BP × positive emotion differentiation interaction was significant in the prediction of urges for bingeing and hitting/throwing, ps = 0.03, but not the other specific behaviors, ps > 0.05.

Table 3.

Hierarchical regression analyses exploring the roles of borderline personality group, emotion differentiation, and their interaction in state urges to engage in maladaptive behaviors.

| Variables | β | R2 (Adj. R2) | ΔR2 | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Positive Emotion Differentiation | ||||

| Step 1 | 0.35 (.33) | 21.75*** | ||

| General psychopathology | 0.54*** | |||

| Affective intensity | 0.10 | |||

| Step 2 | 0.43 (0.40) | 0.08** | 14.59*** | |

| BP group (0 = low BP) | 0.43** | |||

| Positive emotion differentiation | -0.05 | |||

| Step 3 | 0.45 (0.42) | 0.03* | 12.90*** | |

| BP × positive emotion differentiation | -0.19* | |||

| Model 2: Negative Emotion Differentiation | ||||

| Step 1 | 0.33 (0.31) | 18.53*** | ||

| General psychopathology | 0.50*** | |||

| Affective intensity | 0.13 | |||

| Step 2 | 0.41 (0.38) | 0.08** | 12.87*** | |

| BP group (0 = low BP) | 0.47** | |||

| Negative emotion differentiation | 0.03 | |||

| Step 3 | 0.44 (0.40) | 0.03 | 11.45*** | |

| BP × negative emotion differentiation | 0.22 | |||

Note. BP = borderline personality.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Fig. 2.

Interactive effect of borderline personality (BP) group and positive emotion differentiation on state urges for maladaptive behaviors.

The hierarchical regression analysis examining the main and interactive effects of BP and negative emotion differentiation on state urges was significant, R2 = 0.44, p < 0.001. BP group emerged as a significant predictor, β = 0.51, p < 0.001, whereas negative emotion differentiation did not, β = -0.10, p = 0.37. The addition of the BP × negative emotion differentiation interaction did not significantly improve the model, β = 0.22, ΔR2 = 0.03, p = 0.06. However, the direction of the nonsignificant effect was counter to expectations, with the relationship between BP group and state urges for maladaptive behavior nonsignificantly stronger at low levels of negative emotion differentiation.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to examine the role of emotion differentiation in the relationship between BP pathology and impulses for maladaptive behaviors. The results of the present study provide mixed and contradictory support for our hypothesis that the relationship between BP pathology and difficulties controlling impulsive behaviors under distress and state urges for maladaptive behaviors would be weaker at lower levels of emotion differentiation. The ability to differentiate among specific positive emotions was found to moderate the relationship between BP pathology and difficulties controlling impulsive behaviors, as well as heightened state urges for maladaptive behaviors in daily life. Specifically, the association between high BP status and heightened levels of difficulties controlling impulsive behaviors and state urges for maladaptive behaviors was significant among those with low, but not high, levels of positive emotion differentiation. This was not the case, however, for negative emotion differentiation. As such, these results provide preliminary evidence for the role of positive emotion differentiation as a potential protective factor in the relation between BP pathology and maladaptive behaviors.

The present study adds to a growing literature demonstrating that the ability to identify specific emotional experiences constitutes a resilience factor (e.g., Barrett et al. 2001). Consistent with past research (Kashdan et al. 2004), findings highlight the relevance of emotion differentiation to negative outcomes among at-risk groups. Specifically, findings support the role of positive emotion differentiation in reducing state urges for maladaptive behaviors and difficulties controlling impulsive behaviors among persons with high (but not low) levels of BP pathology, even when controlling for general psychopathology and affective intensity. However, these findings suggest that negative emotion differentiation does not impact urges for such behaviors, suggesting that reducing urges may not be the mechanism by which emotion differentiation facilitates non-engagement in maladaptive behaviors.

Although the finding of a relation between positive (but not negative) emotion differentiation and impulses for maladaptive behaviors may appear surprising, it is not without support. In fact, there is evidence to suggest that regulatory difficulties may occur across both negative and positive emotional systems (e.g., Linehan 1993; Linehan, Bohus, and Lynch 2007; Segal, Williams, and Teasdale, 2001). For example, the regulation of positive emotions has been found to be cognitively taxing (Gross and John 2003; Gross and Levenson 1997), which may deplete self-regulatory resources and, subsequently, heighten risk for involvement in maladaptive behaviors (Baumeister, Bratslavsky, Muraven and Tice 1998). Further, there is evidence that individuals may be nonaccepting of positive emotions (e.g., Beblo, Fernando, Klocke, Griepenstroh, Aschenbrenner, and Driessen 2012; Kissen 1986) or seek to avoid physiological arousal associated with positive emotions (see Roemer, Litz, Orsillo, and Wagner 2001; Tull 2006). Additionally, extant literature suggests that positive emotional states increase distractibility (Dreisbach and Goschke, 2004) and lead to less discriminative use of information (Forgas 1992; Forgas and Bower 1987), increasing risk for poor decision-making (Slovic, Finucane, Peters, and MacGregor 2004). Similarly, difficulties regulating positive emotions has been shown to be associated with a range of clinically-relevant maladaptive behaviors (e.g., substance use and risky sexual behavior; Cyders, Flory, Rainer, and Smith 2009; Cyders and Smith 2008; Zapolski, Cyders, and Smith 2009). For instance, positive emotions in particular have been associated with heightened cravings (i.e., for cigarettes; Veilleux, Contrad, and Kassel 2013). Thus, results of the present study extend aforementioned investigations by providing preliminary evidence of the role of positive emotion differentiation (one dimension of emotion regulation) in impulses for maladaptive behaviors.

The question of how the ability to distinguish emotional nuances actually protects individuals with BP pathology from urges for maladaptive behaviors remains unresolved. An inability to differentiate specific emotions has been hypothesized to contribute to difficulties with emotion regulation (Linehan 1993). Emotional responses are often viewed as functional responses to stressors, which can serve as motivators to solve problems or solicit assistance from others via emotional expression. In the absence of correct emotion identification, such problem solving and effective emotional expression may be negatively impacted, thereby heightening distress. By providing a more nuanced understanding of emotional arousal, emotion differentiation may reduce the all-or-nothing, good-or-bad appraisals of emotional experience, thereby reducing fear of emotional experiences, and subsequent arousal. Consistent with this notion, the inability to label emotions has been more strongly linked with distress among persons with BPD than among other groups (Ebner-Priemer et al. 2008). Conversely, clarity regarding emotional experiences may actually decrease arousal. Data from brain imaging studies suggest that labeling emotions (vs. matching emotional facial expressions) results in decreased emotional arousal (Lieberman et al. 2007). Thus, it is possible that emotion differentiation reduces arousal or increases distress tolerance, thereby reducing the need to engage in maladaptive behaviors that may serve to reduce or distract away from distress. Alternatively, emotional differentiation may be one consequence of other contributing factors, such as mindfulness, which has been inversely associated with impulsivity (Peters, Erisman, Upton, Baer, and Roemer 2011). However it remains unclear as to why emotion differentiation with regard to positive, but not negative, emotions may be so important in the link between impulsivity and BP pathology. In the present study, it is possible that the inability to make fine-grained distinctions among negative emotions resulted in more global appraisals of positive emotional experiences (e.g., feeling “good” rather than feeling “alert” or “calm”), resulting in enhanced positive emotional experiences, which may have, in turn, heightened cravings (e.g., Veilleux et al. 2013). Furthermore, there is evidence that the ability to differentiate between negative emotions buffers the impact of rumination on NSSI among individuals with BPD (Zaki et al. 2013). Thus it is possible that the role of negative emotion differentiation on impulsive behaviors in BPD is only evident in the context of use of maladaptive coping styles. While the current study provides preliminary support for the role of positive emotion differentiation in maladaptive behaviors among individuals with high levels of BP pathology, future investigations are needed to clarify the emotion regulatory function of emotion differentiation in maladaptive behaviors.

There were several limitations of the present study. First, we relied upon a college sample, resulting in a relatively young group of participants. Second, we did not conduct diagnostic interviews; thus, findings may not generalize to individuals with clinical diagnoses of BPD (although the PAI-BOR has evidenced good predictive validity of BPD diagnoses; Jacoby et al. 2007). Third, the one-day monitoring period may have been too brief to adequately capture emotion differentiation (although past research has used similar within-day ratings for this construct; Boden, Thompson, Dizén, Berenbaum, and Baker in press) or urges for maladaptive behaviors, and was insufficient to assess actual engagement in maladaptive behaviors. Furthermore, we were unable to examine temporal relationships between changes in emotion differentiation and urges for maladaptive behaviors, and this constitutes an important avenue for future research. Fourth, our supplementary analyses suggesting positive emotion differentiation moderated the impact of BP pathology particularly with regard to urges for binge eating and violent behaviors relied on single-item measurement. Future studies could benefit from more rigorous measurement of specific maladaptive urges and behaviors. Fifth, although several studies have supported similar operationalizations of emotion differentiation used in the present study (Barrett et al. 2001; Boden et al. in press; Kashdan et al. 2010; Tugade et al. 2004; Zaki et al. 2013), this particular definition may conflate the ability to identify experiencing multiple emotions at once with difficulties identifying specific emotions. As such, subsequent studies should incorporate additional measures of emotional clarity. Finally, in the absence of clinical controls, it is unclear whether the protective role of positive emotion differentiation is unique to BPD, or whether this ability serves a similar function across other psychopathologies. Importantly, however, a significant interaction between BP features and positive emotion differentiation on emotion-related difficulties controlling impulsive behaviors and state urges for maladaptive behaviors was detected even when controlling for general psychopathology. Future studies could benefit from the inclusion of diagnostic assessments and longer monitoring periods.

Despite these limitations, results of the present study contribute to our understanding of maladaptive behaviors among individuals with BP pathology. This is among the first studies to highlight a specific domain of emotion regulation as central to the relation between BP pathology and emotion-related difficulties controlling impulsive behaviors and state urges for maladaptive behaviors. Furthermore, these findings bear substantial clinical implications. Specifically, these data underscore the potential utility of teaching individuals with BPD how to differentiate nuances among positive emotions, such as through self-monitoring, mindfulness of positive emotions, or targeted psychoeducation around positive emotions. Such interventions targeting enhancing the ability to distinguish between positive emotions may be particularly important in reducing the maladaptive, potentially self-damaging behaviors characteristic of BPD.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by a President’s Research Grant from Simon Fraser University and a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada Small Research Grant awarded to the second author, and a grant from the National Institutes of Health (T32DA019426) awarded to the third author.

Footnotes

When BP group is examined as the moderator, tests of the slopes of the regression lines revealed that the relationship between positive emotion differentiation and DERS-IMPULSE was significant for the high-BP group (b = -2.71, SE = 0.96, t = -2.83, p = 0.01), but not the low-BP group (b = -0.31, SE = 0.38, t = -0.81, p = 0.42).

When BP group is examined as the moderator, tests of the slopes of the regression lines revealed that the relationship between positive emotion differentiation and state urges for maladaptive behaviors was significant for the high-BP group (b = -0.15, SE = 0.07, t = -2.07, p = 0.04), but not the low-BP group (b = 0.01, SE = 0.03, t = 0.20, p = 0.84).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA, Smith GT, Lykins E, Button D, Krietemeyer J, Sauer S, Walsh E, Duggan D, Williams JMG. Construct validity of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionaire in meditating and nonmedittating samples. Assessment. 2008;15:329–342. doi: 10.1177/1073191107313003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett LF, Gross J, Christensen TC, Benvenuto M. Knowing what you’re feeling and knowing what to do about it: Mapping the relation between emotion differentiation and emotion regulation. Cognition & Emotion. 2001;15:713–724. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Bratslavsky E, Muraven M, Tice DM. Ego depletion: Is the active self a limited resource? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:1252–1265. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.5.1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beblo T, Fernando S, Klocke S, Griepenstroh J, Aschenbrenner S, Driessen M. Increased suppression of negative and positive emotions in major depression. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2012;141:474–479. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk R, MacDonald J. Overdispersion and poisson regression. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 2008;24:269–284. [Google Scholar]

- Boden MT, Thompson RT, Dizén M, Berenbaum H, Baker JP. Are emotional clarity and emotion differentiation related? Cognition & Emotion. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2012.751899. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman AL, Leung DW, Lynch TR. Impulsivity and emotion dysregulation in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2008;22:148–164. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2008.22.2.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman AL, Rosenthal MZ, Leung D. Emotion suppression and borderline personality disorder: An experience-sampling study. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2009;23:27–45. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2009.23.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, West SG, Finch JF. The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychological Methods. 1996;1:16–29. [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Flory K, Rainer S, Smith GT. The role of personality dispositions to risky behavior in predicting first year college drinking. Addiction. 2009;104:193–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02434.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT. Mood-based rash action and its components: Positive and negative urgency. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;43:839–850. [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT. Emotion-based dispositions to rash action: The trait of urgency. Psychological Bulletin. 2008;134:807–828. doi: 10.1037/a0013341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT, Spillane NS, Fischer S, Annus AM, Peterson C. Integration of impulsivity and positive mood to predict risky behavior: Development and validation of a measure of positive urgency. Psychological Assessment. 2007;19:107–118. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR. Symptom checklist-90-R: Administration, scoring, and procedures manua. 3. Minneapolis, MN: National Computer Systems; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Dreisbach G, Goschke T. How positive affect modulated cognitive control: Reduced perseveration at the cost of increased distractibility. Journal of Experimental Psychology - Learning Memory and Cognition. 2004;30:343–353. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.30.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn BD, Billotti D, Murphy V, Dalgleish T. The consequences of effortful emotion regulation when processing distressing material: A comparison of suppression and acceptance. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2009;47(9) doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebner-Priemer U, Kuo J, Schlotz W, Kleindienst N, Rosenthal MZ, Detterer L, Linehan M, Bohus M. Distress and affect regulation in patients with borderline personality disorder: A psychophysiological ambulatory monitoring study. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2008;196(4):314–320. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31816a493f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgas JP. Affect in social judgments and decisions: A multiprocess model. In: Zanna M, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1992. pp. 227–275. [Google Scholar]

- Forgas JP, Bower GH. Mood effects on person-perception judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;53:53–60. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.53.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox HC, Hong KA, Sinha R. Difficulties in emotion regulation and impulse control in recently abstinent alcoholics compared with social drinkers. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33:388–394. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Roemer L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2004;26:41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Tull MT. The relationship between emotion dysregulation and deliberate self-harm among inpatients with substance use disorders. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2010;34:544–553. doi: 10.1007/s10608-009-9268-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross J, John OP. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;85:348–362. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross J, Levenson RW. Hiding feelings: The acute effects of inhibiting positive and negative emotions. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:95–103. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilbe JM. Negative Binomial Regressio. Cambridge University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobo MC, Blais MA, Baity MR, Harley R. Concurrent validity of the Personality Assessment Inventory Borderline Scales in patients seeking dialectical behavior therapy. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2007;88:74–80. doi: 10.1080/00223890709336837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB, Ferssizidis P, Collins RL, Muraven M. Emotion differentiation as resilience against excessive alcohol use: An ecological momentary assessment in underage social drinkers. Psychological Science. 2010;21(9):1341–1347. doi: 10.1177/0956797610379863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissen M. Characterological aspects of depression in borderline patients. Current Issues in Psychoanalytic Practice. 1986;2:45–63. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen RJ, Diener E. Affect intensity as an individual difference characteristic: A review. Journal of Research in Personality. 1987;21:1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Leible TL, Snell WE. Borderline personality disorders and aspects of emotional intelligence. Personality and Individual Differences. 2004;37:393–404. [Google Scholar]

- Liang KY, Zeger SL. Logiudinal data-analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman MD, Eisenberger NI, Crocket M, Tom SM, Pfiefer JH, Way BM. Putting feelings into words: Affect labeling disrupts amygdala activity in response to affective stimuli. Psychological Science. 2007;18:421–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorde. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Bohus M, Lynch TR. Dialectical behavior therapy for pervasive emotion dysregulation: Theoretical and practical underpinnings. In: Gross JJ, editor. Handbook of emotion regulation. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2007. pp. 581–606. [Google Scholar]

- Longford NT. Regression analysis of multilevel data with measurement error. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology. 1993;46(2):301–311. [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, Kurtz JE, Yamagata S, Terracciano A. Internal consistency, retest reliability, and their implications for personality scale validity. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2011;15(1):28–50. doi: 10.1177/1088868310366253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GA, Chapman JP. Misunderstanding analysis of covariance. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110(1):40–48. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modestin J, Furrer R, Malti T. Study on alexithymia in adult non-patients. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2004;56:707–709. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00125-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey LC. Personality Assessment Inventory: Professional Manual. Odessa, Florida: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Muehlenkamp JJ, Ertelt TW, Miller AL, Claes L. Borderline personality symptoms differentiate non-suicidal and suicidal self-injury in ethnically diverse adolescent outpatients. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2011;52:148–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters JR, Erisman SM, Upton BT, Baer RA, Roemer L. A preliminary investigation of the relationships between dispositional mindfulness and impulsivity. Mindfulness. 2011;2:228–235. [Google Scholar]

- Peters JR, Eisenlohr-Moul TA, Upton BT, Baer RA. Nonjudgment as a moderator of the relationship between present-centered awareness and borderline features: Synergistic interactions in mindfulness assessment. Personality and Individual Differences. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Roemer L, Litz BT, Orsillo SM, Wagner AW. A preliminary investigation of the role of strategic withholding of emotions in PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2001;14:149–156. [Google Scholar]

- Salsman NL, Linehan MM. An investigation of the relationships among negative affect, difficulties in emotion regulation, and features of borderline personality disorder. Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Assessment. 2012;34:260–267. [Google Scholar]

- Sansone RA, Levitt JL, Sansone LA. The prevalence of personality disorders among those with eating disorders. Eating Disorders. 2005;13:7–21. doi: 10.1080/10640260590893593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal ZV, Williams JMG, Teasdale JD. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: A new approach to preventing relaps. New York, NY: Guilford; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Slovic P, Finucane ML, Peters E, MacGregor DG. Risk as analysis and risk as feelings: Some thoughts about affect, reason, risk, and rationality. Risk Analysis. 2004;24:311–322. doi: 10.1111/j.0272-4332.2004.00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suvak MK, Litz BT, Sloan DM, Zanarini MC, Barrett LF, Hofmann SG. Emotional granularity and borderline personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120:414–426. doi: 10.1037/a0021808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 4. Pearson Allyn & Bacon; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ. Structural relations between borderline personality disorder features and putative etiological correlates. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:471–481. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.3.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ, Sher KJ, Minks-Brown C, Durbin J, Burr R. Borderline personality disorder and substance use disorders: A review and integration. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;20:235–253. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tugade MM, Fredrickson BL, Barrett LF. Psychological resilience and positive emotional granularity: Examining the benefits of positive emotions on coping and health. Journal of Personality. 2004;72(6):1161–1190. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00294.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tull MT. Expanding an anxiety sensitivity model of uncued panic attack frequency and symptom severity: The role of emotion dysregulation. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2006;30:177–184. [Google Scholar]

- Tull MT, Gratz KL, Weiss NH. Exploring associations between borderline personality disorder, crack/cocaine dependence, gender, and risky sexual behavior among substance-dependent inpatients. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. 2011;2:209–219. doi: 10.1037/a0021878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tull MT, Weiss NH, Adams CE, Gratz KL. The contribution of emotion regulation difficulties to risky sexual behavior within a sample of patients in residential substance abuse treatment. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37:1084–1092. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veilleux JC, Conrad M, Kassel JD. Cue-induced cigarette craving and mixed emotions: A role for positive affect in the craving process. Addictive Behaviors. 2013;38:1881–1889. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss HM, Beal DJ, Lucy SL, MacDermid SM. Constructing EMA studies with PMAT: The Purdue momentary assessment tool user’s manual. Military Family Research Institute Purdue University 2004 [Google Scholar]

- Weiss NH, Tull MT, Viana AG, Anestis MD, Gratz KL. Impulsive behaviors as an emotion regulation strategy: Examining associations between PTSD, emotion dysregulation, and impulsive behaviors among substance dependent inpatients. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2012;26:453–458. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, Lynam DR, Miller JD, Reynolds SK. Validation of the UPPS Impulsive Behavior Scale: A four-factor model of impulsivity. European Journal of Personality. 2005;19:559–574. [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside U, Chen E, Neighbors C, Hunter D, Lo T, Larimer M. Difficulties regulation emotions: Do binge eaters have fewer strategies to modulate and tolerate negative affect? Eating Behaviors. 2007;8:162–169. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams AD, Grisham JR, Erskine A, Cassedy E. Deficits in emotion regulation associated with pathological gambling. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2012;51:223–238. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.2011.02022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff S, Stiglmayr C, Bretz HJ, Lammers CH, Auckenthaler A. Emotion identification and tension in female patients with borderline personality disorder. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2007;46:347–360. doi: 10.1348/014466507X173736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaki LF, Coifman KG, Rafaeli E, Berenson KR, Downey G. Emotion differentiation as a protective factor against nonsuicidal self-injury in borderline personality disorder. Behavior Therapy. 2013;44:529–540. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2013.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapolski TCB, Cyders MA, Smith GT. Positive urgency predicts illegal drug use and risky sexual behavior. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23:348–354. doi: 10.1037/a0014684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]