Abstract

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), a noninvasive neuroimaging method that provides an indirect measure of neuronal activity by detecting blood flow changes, has experienced an explosive growth in the past years. Statistical methods play a crucial role in understanding and analyzing fMRI data. Bayesian approaches, in particular, have shown great promise in applications. A remarkable feature of fully Bayesian approaches is that they allow a flexible modeling of spatial and temporal correlations in the data. This paper provides a review of the most relevant models developed in recent years. We divide methods according to the objective of the analysis. We start from spatio-temporal models for fMRI data that detect task-related activation patterns. We then address the very important problem of estimating brain connectivity. We also touch upon methods that focus on making predictions of an individual's brain activity or a clinical or behavioral response. We conclude with a discussion of recent integrative models that aim at combining fMRI data with other imaging modalities, such as EEG/MEG and DTI data, measured on the same subjects. We also briefly discuss the emerging field of imaging genetics.

Keywords: Bayesian Statistics, Brain Connectivity, Classification and Prediction, fMRI, Spatio-Temporal Activation Models

Introduction

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) is a noninvasive neuroimaging method that measures blood-oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) signals in the brain in vivo. Neural activity is associated with localized changes in metabolism. As a brain area becomes active, for example in response to a task, there is an increase in local oxygen consumption and, consequently, more oxygen-rich blood flows to the active brain area. Thus, activated brain areas show a relative increase in oxyhemogloblin and a relative decrease in deoxyhemoglobin, as the increased supply of oxygen outpaces the increased demand for it. BOLD signals measure metabolic activity in the brain as the difference between the oxyhemoglobin and deoxyhemoglobin levels arising from changes in local blood flow.

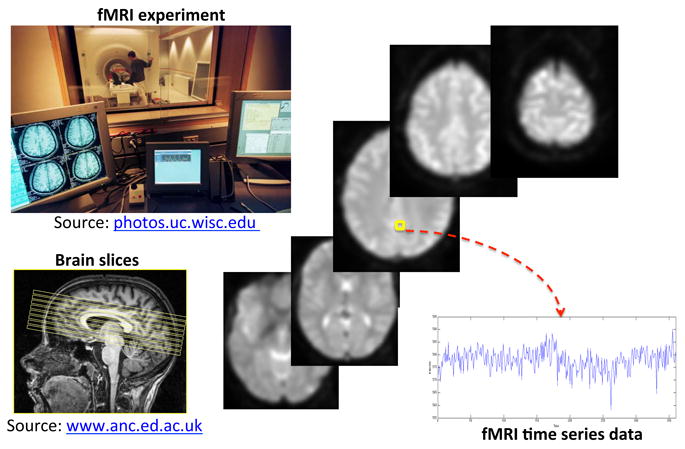

Figure 1 illustrates a typical fMRI experiment. Distributed three-dimensional (3D) maps of localized brain activity are measured over time while the subject lies in the MRI scanner. Scans are typically acquired every two to three seconds, with each scan arranged in a three dimensional array of volume elements (or “voxels”). Time series of BOLD responses are produced at every voxel, as the temporal evolution of brain activity at that location. An fMRI experiment on a single subject can yield hundreds of scans in a single session. fMRI data are therefore massive collection of hundreds of thousands of time series, arising from spatially distinct locations.

Figure 1.

Typical fMRI experiment: 3D maps are acquired over time while the subject lies in the scanner, producing time series of fMRI BOLD responses measured at each brain voxel. Selected 2D arrays, corresponding to axial slices across the third dimension, are shown.

Statistical methods play a crucial role in the analysis of fMRI data7,68,76,96, due to the complex spatial and temporal correlation structure of the data, as well as their large dimensionality. Early approaches to the analysis of such data would calculate voxel-wise t-test or ANOVA statistics and/or fit a linear model at each voxel after a series of preprocessing steps, including scanner drift and motion corrections, adjustment for cardiac and respiratory-related noise, normalization and spatial smoothing, see Huettel et al.54, Chapter 10. However, spatial correlation is expected in a voxel-level analysis of fMRI data because the response at a particular voxel is likely to be similar to the responses of neighboring voxels. Also, correlation among voxels does not necessarily decay with distance. All this makes single-voxel approaches not appropriate, as the test statistics across voxels are not independent. In addition, serious multiplicity issues arise, due to the large dimensionality of the data.

This paper provides a review of the most relevant Bayesian modeling approaches to fMRI data analysis that have been developed in recent years. Bayesian approaches have a great potential in applications as they allow a flexible modeling of spatial and temporal correlations in the data126. We divide methods according to the objective of the analysis. We start from spatio-temporal models that estimate task-related activation patterns. In a typical task-related fMRI experiment, the whole brain is scanned at multiple times while a subject performs a series of tasks. The objective of the analysis is then to detect those brain regions that get activated by the external stimulus. We discuss general linear and nonlinear models, as well as mixture models, for both single- and multiple-subject studies.

Another important task in fMRI studies, which has received increased interest in recent years, is to infer brain connectivity. In general terms, connectivity looks at how brain regions interact with each other and how information is transmitted between them, with the aim of uncovering the actual mechanisms of how our brain functions. We discuss Bayesian approaches for both functional (undirected) and effective (directed) connectivity, as first defined by Friston27. Functional connectivity studies seek to identify multiple brain areas that exhibit similar temporal profiles, either task-related or at rest, while effective connectivity seeks to estimate the directed influence of one brain region on another.

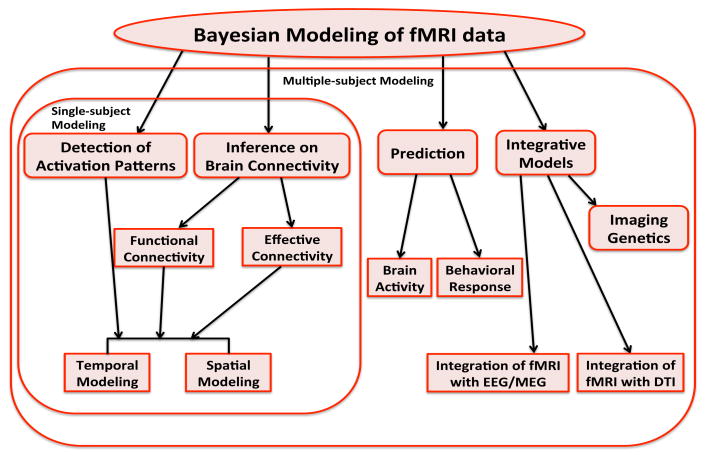

In the last part of our review, we touch upon methods that focus on making predictions of an individual's brain activity or a clinical or behavioral response and then conclude the paper with a discussion of recent integrative models that aim at combining fMRI data with other imaging modalities, such as EEG/MEG and DTI data, measured on the same subjects. We also briefly discuss the emerging field of imaging genetics. Figure 2 shows an outline of our review.

Figure 2.

Outline of the Bayesian methods for fMRI data reviewed in this paper. Methods are divided according to the objective of the analysis.

Detection of Activated Brain Regions

Detecting brain regions activated by an external stimulus or condition is probably the most common objective in fMRI studies. Neuronal activation in response to a stimulus occurs in milliseconds and cannot be observed directly. However, neuronal activation is followed by the metabolic process which increases blood flow and volume in the activated areas, and can therefore be measured by fMRI.

Single-subject modeling

In a typical task-related fMRI experiment, the whole brain is scanned at multiple times while a subject performs a series of tasks, and a time series of BOLD response is acquired for each voxel of the brain.

The most common statistical model of a time series of BOLD responses relies on the Gaussian linear model, known as general linear model (GLM) in the fMRI literature, as first proposed by Friston et al.31. This models the observed fMRI signal as the underlying BOLD response plus a noise component. Let Yυ be the T × 1 response vector of time series data for voxel υ, for υ = 1, …, V, with T the number of time points and V the number of voxels, and let Xυ be the T × p design matrix, with p being the number of experimental tasks or input stimuli. We write the voxel-wise general linear model as

| (1) |

where βυ = (βυ,1, …, βυ,p)T is a p × 1 vector of regression coefficients and ∈υ is a T × 1 error vector. The error component in (1) captures random noise and various nuisance components due to the hardware as well as subject-related physiological noise.

Let's consider the underlying BOLD response component Xυβυ in model (1). This captures the relationship between the vascular response and the stimulus as follows. When measuring the change in the metabolism of BOLD contrast due to an outside stimulus, the MR signal gets delayed hemodynamically12. Such a hemodynamic response is typically referred to as the hemodynamic response function (HRF). A widely used model to account for the lapse of time between the stimulus onset and the vascular response looks at the BOLD signal as the convolution of the stimulus pattern with the HRF. This implies that in model (1) each column (task or input stimulus) of Xυ is modeled as

| (2) |

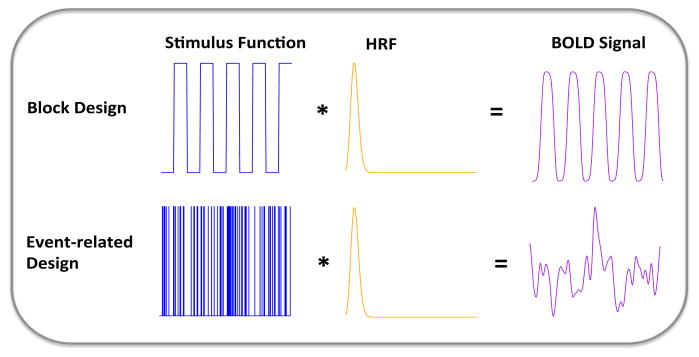

where x(s) represents the external time-dependent stimulus function for that particular task, which is known and corresponds to the experimental paradigm (for example, a vector defined with elements set to 1 when the stimulus is “on” and 0 when it is “off”). Figure 3 depicts such BOLD signal modeling for two commonly used experimental designs, block and event-related.

Figure 3.

Typical modeling of the BOLD signal at a given voxel, for both block and event-related designs. The BOLD signal is modeled as the convolution of the experimental stimulus and the hemodynamic response function (HRF).

Several models for the HRF hυ(t) have been proposed. Early proposals included Poisson31 functions of the type

| (3) |

Gaussian32 functions and gamma functions67 of the type

| (4) |

More common choices include the Canonical HRF, defined as the difference of two gamma functions33

| (5) |

and the inverse logit function77, which is generated as a superposition of three separate inverse logit functions, that is,

| (6) |

with L(x) = 1/(1 + e−x).

Several Bayesian approaches to models of type (1) have been investigated in the literature and successfully applied to fMRI data24,29,43,48,50,57,62,70,93,94,97,108,109,127,132,139.

These employ hierarchical models that make explicit assumptions on the model parameters, allowing inference via posterior densities. A remarkable feature of such approaches is their flexibility in modeling temporal and spatial correlation features of the data.

Temporal Modeling

Clearly, some of the temporal correlation of fMRI data is captured via the modeling of the HRF, as described above. As temporal characteristics of the HRF vary across brain voxels, and across subjects, some authors have employed Bayesian models of type (1) where the parameters of the HRFs are voxel-dependent97,127,139, while Xia et al.132 have proposed to model the HRF at each voxel non-parametrically.

A significant amount of work has been done in capturing temporal correlation in fMRI data via the choice of the noise structure. One approach, often used in the classical literature on fMRI data, is to prewhiten the data by obtaining an initial estimate of the autocorrelation structure, based on the data, and then removing this correlation by applying a transformation to the data31. Other approaches, particularly in the Bayesian literature, look at directly modeling the error term. The most common choice is to impose an autoregressive structure of order q (AR(q)) on ∈υ in (1),

| (7) |

with wυ = (ωυ,1, …, ωυ,q)T a q × 1 vector of AR coefficients and zυ,t a white noise, assuming prior distributions on the AR coefficients70,93,94,127. An important source of variability in the signal results from scanner drift, which induces slow changes in voxel intensity over time (low-frequency noise), and physiological noise, due to patient motion, respiration and heartbeat causing fluctuations in signal across both space and time. To account for this, a level shift or deterministic trend, modeled, for example, as a pth order polynomial function, can be included in model (1)76,131. Alternatively, wavelet transforms can be used to filter noise125. In the Bayesian literature, Jeong et al.57 and Zhang et al.139 considered a general error structure

| (8) |

with Συ(m, n) = [γ(|m − n|)] and γ(h) the auto-covariance function of the process generating the data, and modeled the correlated noise as being from a 1/f long memory process107. The authors applied discrete wavelet transforms (DWT) to model (1), transforming the data into the following model in the wavelet domain

| (9) |

with and W an orthogonal T × T matrix representing the wavelet transform, and performing inference on the model parameters based on the transformed data. Wavelet transforms have the advantage of “whitening” the data, i.e., reducing the dense covariance matrix structure of the long memory to i.i.d. errors 11,22,84.

Spatial Modeling

Spatial correlation is expected in a voxel-level analysis of fMRI data because the response at a particular voxel is likely to be similar to the responses of neighboring voxels. In Bayesian modeling, spatial dependence between brain voxels is captured by imposing spatial priors on the model parameters. Many approaches use Gaussian Markov random field (GMRF) priors on the jth regression coefficient vector β(j) = (β1,j, …, βV,j)T43,97 of the type

| (10) |

with precision matrix Q having elements

| (11) |

with nυ the number of neighbors of voxel υ, and with υ ∼ k denoting that voxels υ and k are neighbors. Prior (10) with precision matrix Q as in (11) is equivalent to

| (12) |

from which we have

| (13) |

where β−υ,j = {βl,j; l ≠ υ}. Similarly, Penny et al.94 considered a spatial prior on the regression coefficient vector β(j) of the type

| (14) |

with S a V × V spatial kernel matrix equal to the Laplacian operator L, i.e., if w(j) = Lβ(j) then ωυ,j is equal to the sum of the differences between βυ,j and its neighbors, for υ = 1, …, V, and αj a spatial precision parameter. Each element of w(j) follows a zero-mean Gaussian distribution with precision αj. Other spatial prior constructions on the regression coefficients that have been investigated in the literature include the diffusion-based spatial priors of Harrison et al.50 and the conditional autoregressive (CAR) priors of Harrison and Green48, while Flandin and Penny24 used sparse spatial basis function (SSBF) priors on wavelet-based regression coefficients.

Alternative modeling approaches to those described above look at the task of selecting activated voxels as a variable selection problem, that is the identification of the nonzero βυ,j in model (1). A common class of priors adopted in the Bayesian literature on variable selection specifies mixture distributions with a spike at zero (commonly called spike-and-slab priors) on the regression coefficients9,38,106. For model (1) we can write

| (15) |

with γυ = (γυ,1, …, γυ,p) binary indicators representing the activation status, i.e., βυ,j = 0 if γυ,j = 0, for inactive voxels, and βυ,j ≠ 0 if γυ,j = 1, for active voxels, for j = 1, …, p, and with I(A) the indicator function equal to 1 if A is true and 0 otherwise62,70,108,139. Kalus et al.62 considered the case p = 1 and specify a spatial probit model for the prior probabilities of activation, that is P(γυ = 1) = Φ(αυ), with Φ the standard normal cdf and α = (α1, …, αV)T following a Gaussian Markov random field (GMRF) prior. Specifically, the authors considered a first order intrinsic GMRF (IGMRF) prior

| (16) |

with Q as in (11) and ξ2 a variance parameter determining the degree of smoothness, or a CAR prior of the type

| (17) |

with P = I + τ2 Q and τ2 > 0 modeled by a positively truncated Normal prior. Alternatively, Zhang et al.139 specified a Markov Random Field (MRF) prior on γυ, parameterizing its conditional probability as

| (18) |

with Nυ the set of neighboring voxels of voxel υ, d ∈ (−∞,∞) a sparsity parameter controlling the expected prior number of activated voxels and e > 0 the smoothing parameter which affects the probability of identifying a voxel as active according to the activation of its neighbors. Smith and Fahrmeir108 and Lee et al.70 considered spatial MRF priors for the case p > 1, incorporating anatomical prior information as well as spatial interaction between voxels. They wrote the prior on γ = {γυ,j, υ = 1, …, V, j = 1, …, p} as , where γ(j) = (γ1,j, …, γV,j)T and

| (19) |

with , called the “external field”, capturing anatomical prior information, typically as a linear combination of the parameters αυ,j(γυ,j) = αυ,jγυ,j, with scalars αυ,j fixed a priori, and with the second term in the exponential function being the interaction effect of neigbouring voxels υ and k, with pre-specified weights ωυ,k (typically, it is assumed θυ,k,j = θj). Smith et al.109 and Xia et al.132 also considered a spatial prior of type (19).

As a point of summary, among the contributions we have described above, Lee et al.70 and Penny et al.94 model both temporal and spatial correlations but assume pre-specified HRFs, while Zhang et al.139 also include the estimation of the HRF. Woolrich et al.127 impose a nonseparable space-time vector autoregressive structure on the error term of the model and incorporate the estimation of the HRF. Flandin and Penny24, Gössl et al.43, Harrison and Green48, Kalus et al.62, Quirós et al.97, Smith and Fahrmeir108, Smith et al.109 make use of spatial priors on the model parameters but assume independent error terms. Gössl et al.43 and Quirós et al.97 also incorporate the estimation of the HRF.

MCMC and Scalability

Many of the Bayesian approaches described above achieve posterior inference via numerical integration methods, such as Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling algorithms43,57,62,70,97,108,109,127,132,139. These models are often fit to single 2D slices, as the large dimensionality of the data makes it impossible to model the entire 3D map of the data at once. Nevertheless, MCMC requires a large amount of computer time, even when inference is limited to single slices. This has motivated many authors to investigate alternative techniques for Bayesian inference that do not rely on numerical integration. A common approach is to employ Variational Bayes (VB) methods. Penny et al.93 first proposed the use of a VB method for inference in a general linear model of type (1) with AR errors, and several other authors have adopted VB methods since then24,48,94,128. The basic idea of VB methods is to approximate the true posterior density with an analytically tractable form by using a factorization of the posterior distribution over the model parameters.

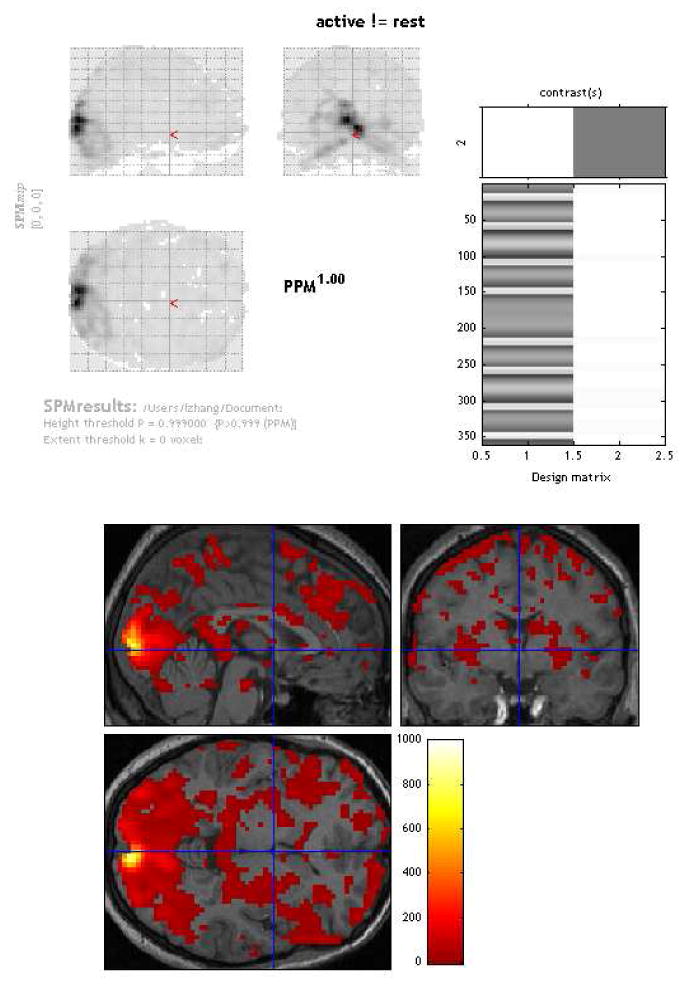

Posterior Probability Maps

For posterior inference, the major goal is to produce a spatial mapping of the activated brain regions. This can be achieved via inference on the regression parameters βυ's in model (1). In particular, activations can be detected by constructing posterior probability maps (PPMs) based on the estimated regression parameters, for example as done by Friston et al.26 and Friston and Penny29. These authors proposed to detect activations by mapping the estimates of the model parameters at each voxel of single slices of imaging data and then thresholding the corresponding conditional posterior probabilities at a specified confidence level. Specifically, at each voxel the conditional posterior probability that a particular effect, specified by a contrast weight vector w, exceeds some threshold κ is calculated as

| (20) |

with Mβυ|Y and Cβυ|Y the posterior mean and covariance of the parameter βυ, respectively. PPMs can be displayed as images, see Figure 4 for an example.

Figure 4.

Top left: An Example of PPMs generated with the software SPM8 (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm). Top right: Design matrix. Bottom: Overlay of χ2 statistic values showing regions where activity is different between active and rest conditions.

When spike-and-slab priors of type (15) are employed, PPMs can be obtained directly by thresholding the activation probabilities p(γυ,j = 1|Y). In particular, an individual voxel can be classified as active if p(γυ,j = 1|Y) > ϱ, and as inactive otherwise, with ϱ a threshold to be chosen. There are several ways to decide the value of the threshold. Smith et al.109, Smith and Fahrmeir108 and Lee et al.70 suggested ϱ = 0.8722, following Raftery98 who considered the statistic −2log(1 − p(γυ,j = 1|Y))/p(γυ,j = 1|Y) approximately distributed χ2(1) and solved the threshold at a critical value of 3.841, for a p value of 0.05. Kalus et al.62 suggested choosing the threshold based on the Bayesian false discovery rate (FDR)88. The decision on the optimal threshold can also be formulated in a compound decision theoretic framework, by minimizing a loss function defined as a linear combination of false positive and false negative counts87. Sun et al.116 have recently shown that procedures thresholding posterior probability maps allow to control also the frequentist FDR in large-scale spatial multiple testing.

Nonlinear and Mixed Models

Many investigators have acknowledged the presence of nonlinearities in BOLD responses, particularly for event-related designs34,124, both across brain regions and stimuli. Among the Bayesian contributions, Genovese37 presented a nonlinear Bayesian hierarchical model that included the estimation of the drift function and the HRF, assuming independent error terms and without taking into account spatial correlation. Also, Yue et al.135 proposed a Bayesian adaptive spatial smoothing approach to capture non-stationary spatial correlation, with a Gaussian smoothing kernel varying across space and time. Their model can be written as

| (21) |

for j = 1, …, n1 and k = 1, …, n2, with yjk the fMRI response data observed at location [uj, uk], at a given time point, and with f an unknown function representing the smoothed image. The authors applied their model to the raw fMRI data at each time point, independently, imposing a spatially adaptive IGMRF prior on the function f and assuming independent errors.

Another class of models that has been quite successful for the analysis of fMRI data, particularly in the Bayesian literature, is mixture models. Here the idea is to characterize the spatial distribution of the data via a (possibly infinite) mixture of distributions, each capturing a distinct cluster of activations. These models are often applied to processed data, either “contrast” maps, obtained by estimating the β coefficients of a general linear model fitted to the fMRI time-series data, or simple z-statistic images. Woolrich et al.129 first considered finite mixture models with adaptive spatial regularization priors on the model parameters. Their model was implemented in the software FSL. Other authors have considered infinite mixture model with Dirichlet process (DP) priors that enable learning on the number of components from the data58,66.

A formal definition of a DP, a stochastic process commonly used in Bayesian nonparametric inference, was first given by Ferguson23. Here it suffices to consider a DP as a prior on a class of probability distribution. Let G denote such random probability measure on the distribution space, with

| (22) |

indicating that the model depends on two parameters, the base measure G0 and the total mass parameter η. The base measure G0 is the prior mean of G, i.e. E(G) = G0. Typically, the unknown G is centered around a known parametric model, while the total mass parameter η determines the variation of the random measure around the prior mean, with smaller values of η implying higher uncertainty. Any realization G from a DP defines a discrete distribution almost surely. Let φi | G ∼ G, i = 1, …, n, be an i.i.d. sample from a distribution G, then G can be almost surely written as a mixture of point masses,

| (23) |

with , Vj ∼ Beta(1, η), j = 1, …, h, and atoms , h = 1, …, ∞. The discreteness of the DP is best appreciated by looking at the predictive distribution of φi, conditional on all the other values φ− i = {φj : j ≠ i},

| (24) |

which gives positive probability to ties, therefore implying that the φi's can form clusters. The parameter η acts as a weight, i.e., the larger η, the higher the probability that φi is sampled from the base measure G0 and thus the larger the number of clusters.

For fMRI data analysis, Kim et al.66 used mixture models with DP priors to model processed data of the type yυ, υ = 1, …, V, with yυ the estimate of the β coefficient of a GLM fitted to fMRI time-series data at voxel υ at position xυ = (xυ1,xυ2),

| (25) |

with C a set of component labels, p(yυ|c, xυ,θ) a Gaussian-shaped surface model for each of the mixture components, and with a DP prior imposed on the component label cυ, υ = 1, …, V. Also, Johnson et al.58 considered an infinite mixture model applied to z-scores yυ, υ = 1, …, V. The model is conditional upon a latent activation state cυ ∈ {−1, 0, 1}, υ = 1, …, V, with labels -1, 0, and 1 denoting three classes/states as deactivated, null, and activated, respectively. With a non-parametric hidden Markov random field model (Potts model) imposed on c, the model is given by

| (26) |

with Fm a Gaussian distribution with parameters and Gm0 a Gaussian distribution with mean μm0 and .

Multiple-subject Modeling

Spatio-temporal models of type (1) have been also extended to multiple subjects6,103. The model becomes

| (27) |

with βiυ = (βiv1, …, βiυp) and βiυk the effect corresponding to condition k on voxel υ for subject i.

The computational challenge of fitting spatio-temporal models of type (27) to voxel-wise data on multiple subjects has motivated researchers to adopt approaches where voxels are grouped into regions of interest (ROIs) and “summary statistics” are calculated for each ROI, so that inference at the group level is based on the summary statistics from the lower level. This approach has also been dominant in the frequentist literature, under the name of group analysis, where GLM-based estimates of the regression parameters obtained at the voxel level are treated as summary statistics at the group level53. One Bayesian approach to group analysis was proposed by Su et al.115, who used a hierarchical model with shrinkage estimation of residual variance by combining information across voxels.

Other Bayesian approaches have used two-stage modeling. Bowman et al.6 combined whole-brain voxel-by-voxel modeling and ROI analysis within a Bayesian hierarchical framework aiming at the detection of task-related activated brain regions. At the first stage a voxel-wise general linear model is fitted for each subject, assuming serially correlated errors and a pre-specified HRF. At the second stage, the authors considered an anatomical parcellation of the brain consisting of G regions and defined a contrast fMRI BOLD response vector associated with stimulus j as βigj = (βig(1)j, …, βig(Vg)j)T, with Vg the number of voxels in region g = 1, …, G. They then fit a spatial hierarchical model of the type

| (28) |

with μgj = (μg(1)j, …, μg(Vg)j)T, and αij = (αi1j, …, αiGj)T.

A different two-stage modeling approach was put forward by Sanyal and Ferreira103, who first fit a general linear model of type (27), assuming independent errors and regressor Xiυ as convolution of the stimulus function with an empirically derived subject-specific HRF. The authors first estimated the regression coefficients by an empirical Bayes methodology and then transformed the estimated standardized coefficients via discrete wavelet transforms to obtain a model in the wavelet space, where they imposed spike-and-slab priors on the wavelet coefficients, extending the wavelet basis prior of Flandin and Penny24 from one subject to multiple subjects.

Bayesian mixture models have also been successfully applied in multi-subject fMRI studies, to capture clusters of activation. Xu et al.133 developed a spatial model for multiple-subject fMRI data to capture the inter-subject variability in activation locations. The authors considered scalar t-images, obtained by fitting an intra-subject fMRI model to each subject, and modeled those via a Gaussian mixture with an unknown number of components. Bayesian nonparametric methods for infinite mixtures were employed by Thirion et al.117 to model the spatial positions of brain regions. For subject s and ROI j, their model can be written as

| (29) |

with the spatial coordinates of the center of the areas related to which is the corresponding ROI for subject s, j = 1, …, I(s), and with denoting the cluster to which is associated. The model infers spatial ROIs activations at group level while computing inter-subject correspondence via Bayesian network models. Jbabdi et al.56 imposed a hierarchical Dirichlet process mixture model on voxel-wise connectivity scores.

Brain Connectivity

While constructing maps of brain regions activated by specific stimuli is certainly of major interest in imaging studies, another important task, which has received increased interest in recent years, is to infer brain connectivity. In general terms, connectivity looks at how brain regions interact with each other and how information is transmitted between them, with the aim of uncovering the actual mechanisms of how our brain functions. General interest in connectivity studies may be in comparing connectivity properties among subgroups of subjects and between different scanning sessions. Such studies often look at resting state data, as opposed to task data. Also, of major interest is to understand the role that connectivity patterns, and their disruption, play in mental health disorders and brain diseases.

As defined in the fMRI literature27, two types of connectivity can be inferred based on fMRI data: Functional connectivity is defined as the undirected association, or temporal correlation, between BOLD signals from spatially remote brain regions, while effective connectivity is the directed influence of one brain region on other regions. Friston28 provided a nice review on functional and effective connectivity.

Functional Connectivity

Functional connectivity aims at identifying parts of the brain showing similar temporal characteristics and, as such, can be quantified using statistical measures of dependence among remote neurophysiological events. In the classical literature, simple approaches to capture functional connectivity are based on temporal correlations between regions of interest, or between a “seed” region and other voxels throughout the brain137. Alternative approaches include clustering methods, to partition the brain into regions that exhibit similar temporal characteristics, and multivariate methods for dimension reduction, such as Principal Components Analysis (PCA)1 and Independent Components Analysis (ICA)14,82, which determine spatial patterns that account for most of the variability in the time series data. Approaches that allow to estimate partial correlations between predefined regions of interest (ROIs) have also been proposed, for example by using the graphical Lasso (GLasso), which estimates a sparse precision matrix16,122.

Initial efforts in the development of Bayesian methods to assess functional connectivity were put forward by Patel et al.91,92, who dichotomised the time series data based on a threshold to indicate presence or absence of elevated activity at a given time point and then modeled the relationship between pairs of distinct brain regions by comparing expected joint and marginal probabilities of elevated neural activity. In their two-stage modeling approach, Bowman et al.6 employed a measure of the strength of task-related intra-regional (or short-range) connectivity based on model (28) defined as

| (30) |

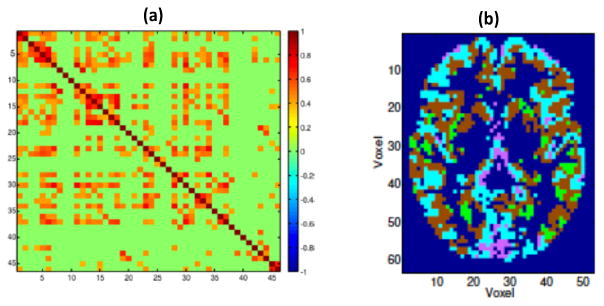

where reflects the similarity in the neural activity between voxels within a given brain region g and is gth diagonal element of Γj. The authors also defined an interregional (or long-range) connectivity between regions g1 and g2 (see Figure 5 (a)) as

Figure 5.

Functional connectivity. (a) Matrix of posterior estimates of inter-regional correlations (Bowman et al.6); (b) Posterior clustering map of spatially remote voxels (Zhang et al. 139).

| (31) |

In their estimation approach to spatio-temporal Bayesian models of type (1), Zhang et al.139 allow clustering of spatially remote voxels that exhibit fMRI time series with similar characteristics (see Figure 5 (b)), by imposing Dirichlet Process (DP) prior on the parameters of long memory error term (8). The induced clustering can be viewed as an aspect of functional connectivity, as it naturally captures statistical dependencies among remote neurophysiological events.

In addition, there has been recent interest in dynamic functional connectivity models that investigate temporal dynamic interactions among brain regions. Zhang et al.138 proposed a dynamic Bayesian variable partition model that simultaneously infers global functional interaction patterns within brain networks and their temporal transition boundaries.

Effective Connectivity

Non-generative modeling measures of connectivity based on statistical dependence, such as temporal correlation, can be affected by spurious results, as they can change between conditions or groups simply due to changes in, for example, the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in the data28. Effective connectivity employs biologically plausible generative models of a typically small network of connected brain regions, assessing the statistical significance of the individual directed connections and effectively modeling the SNR. Being activity-dependent, effective connectivity is dynamic, that is, time-varying, in nature. Effective connectivity refers to causal dependence, as opposed to simple association. Commonly used approaches therefore include many of the methods typically employed to represent causal analysis. The most successful have been Structural Equation Modeling (SEM)10,83, Dynamic Causal Modeling (DCM)35, vector autoregressive (VAR) models49, Granger causality40 and Bayesian networks140. It should be pointed out, however, that even though such methods allow inference on directed connections between brain regions, none of them is able to measure physiological causality, as the direct influence of one region on another, which is ultimately where the scientific interest lies.

Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was proposed for use in econometrics, and then applied to functional brain imaging data by Mclntosh and Gonzalez-Lima83. Most of the existing methods use frequentist approaches, with the exception of Scheines et al. 105.

Granger causality (GC) was first defined by Granger44 for temporally structured data, such as time-series data. In its most general terms, GC does not rely on the prior specification of a structural model, but it is rather based on the idea that causes always precede effects. Therefore, past signal values from one brain region can be used to predict current values in another region. However, methods that directly model Granger causality cannot be applied to fMRI data, due mostly to the mismatch between the sampling interval of the data and the much faster timings of the neurodynamics events110,111, resulting in GC mainly estimating causal interactions in the observed BOLD signals, rather than in the underlying neuronal responses. GC also does not properly take into account the experimentally induced modulatory effects while estimating causal interactions25.

A certain type of Granger causality can be expressed in a state space form via vector autoregressive (VAR) models, as these models nicely account for time-varying parameters51. Let yg(t) be the measured BOLD response for the gth region at time t, with g = 1, …, G and t = 1, …, T, and let xg(t) be the expected BOLD response. Then a model for the observed fMRI signal can be specified as

| (32) |

where αg and βg(t) are the baseline and time-varying activation coefficients for the gth region at the tth time point. Assume that xg(·) = x(·), βg(t) can be modeled in terms of the noise-free BOLD response in the other regions at the previous time point t − 1 as

| (33) |

where ωg(t) are independent zero-mean normal distributed errors and the effective connectivity parameter γgl(t) is the influence of the lth region on the gth region at time t. Equations (32) and (33) specify a type of VAR model. The objective is to make inference on the parameters γgl(t), that capture effective connectivity. In the Bayesian literature, Bhattacharya et al.4 proposed a symmetric random walk model for γgl(t),

| (34) |

with δgl independent zero-mean normal distributed errors, while Bhattacharya and Maitra3 used nonparametric DP priors on Γgl = (γgl(1), …, γgl(T))T,

| (35) |

with g, l = 1, …, G, and with G(T) a T-variate distribution with mean being the T-variate distribution implied by a standard time series such as AR(1). Yu et al.134 used a slightly different model, by imposing a VAR-type structure on the noise term in (32), defining effective connectivity in terms of the corresponding VAR coefficients, and then using spike-and-slab priors on the VAR parameters to select the effective connectivities. Their model also leads to a measure of conditional and overall functional connectivity between ROIs based on precision matrix of the temporally uncorrelated noise component. As inference on VAR models is computationally challenging, due to the large size of the model space, applications of such models are typically done by considering a relatively small number of pre-selected regions, on single subjects. Recently, Gorrostieta et al.42 have developed a Bayesian hierarchical VAR model for effective connectivity in multiple subjects, accounting for the variability in the connectivity structure within and between subjects.

Other much more sophisticated classes of state space models have recently been developed to model effective connectivity. For example, Ryali et al.101 proposed a class of multivariate dynamical models that used vector autoregressive state-space models incorporating both intrinsic and modulatory causal interactions. Intrinsic interactions reflect causal influences independent of external stimuli and task conditions, while modulatory interactions reflect context dependent influences. Causal interactions are modeled at the level of latent signals, rather than at the level of the observed BOLD-fMRI signals.

Directed acyclic graphs, or Bayesian networks (BNs), represent putative causal links between a set of variables in terms of conditional independence. Dynamic Bayesian networks (DBNs), which takes into account the dynamic nature of the process, make use of VAR-type time series modeling to represent Granger causality. These approaches have been recently used to reveal effective connectivity among brain regions65,73,74,75,99. Kim et al. 65 used a discrete dynamic Bayesian network (dNBN) to discriminate brain regions between schizophrenic patients and healthy controls, measuring effective connectivity by the relative likelihood of correlations between brain regions in one group versus another. Rajapakse and Zhou99 employed dynamic Bayesian networks and Li et al.73 compared multiple-subject approaches that either pool the data or learn a separate BN for each subject or place the same BN structure on each of the subjects. Li et al.74 and Li et al.75 inferred effective connectivity among multiple resting-state networks (RSNs) in the brain by using a group independent component analysis (ICA) first, to identify the RSNs, and then applied a BN learning approach to infer the conditional dependencies among RSNs.

Another popular approach to effective connectivity is Dynamic Causal Modeling (DCM), originally proposed by Friston et al.35. Stephan et al.112 offered a nice review of the approach and its applications to fMRI data. DCM models interactions among brain regions directly at the neuronal level using fMRI time series at the hemodynamic level. These models heavily rely on complex biological assumptions, such as how the neuronal states enter a region-specific hemodynamic model to produce the BOLD responses. These assumptions have not yet been adequately verified119. The basic idea under DCM is to treat the brain as a nonlinear dynamic system with multiple inputs and outputs. Effective connectivity is parameterized in terms of the coupling among unobserved neuronal activity in different regions. The coupling parameters are estimated via perturbing the system, adapting to the fMRI experimental inputs (e.g. stimulus function), and measuring the response. The gen eral mathematical framework of DCM is based on differential equations. More specifically, DCM for fMRI models state changes in a system (or network) of n interactive brain regions, with each region being represented by a state variable, via a bilinear differential equation of the type

| (36) |

where θ = (A, B, C) are the neuronal parameters defining connectivity, or coupling, and interactions between brain regions. In particular, the matrix A is a fixed connectivity matrix representing the intrinsic connectivity among the brain regions in the absence of inputs, Bj represents changes in connectivity induced by the jth input and the matrix C reflects the strength of extrinsic influence of the inputs on neuronal activity. Based on state equation (36), the parameters θ can be written as

| (37) |

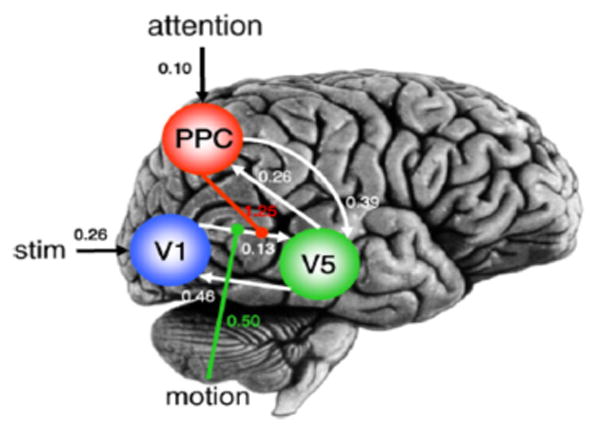

DCM models are quite complex in structure and inference is usually infeasible with more than a few regions. Bayesian approaches have been particularly helpful for model parameter estimation20,30,36,71,113. Typically, Normal priors are placed on the model parameters and an optimization scheme is used to estimate parameters that maximize the posterior probability. The posterior density is then used to make inferences about the significance of the connections between various brain regions. Stephan et al. 113 proposed a nonlinear extension of DCM, augmenting the state equation (36) with additional nonlinear terms representing how connection strengths change due to the activity of other brain regions (see Figure 6). Daunizeau et al.20, Li et al.71 used stochastic dynamic models that accommodate for random fluctuations in neuronal states, allowing application to resting-state fMRI data. Friston et al.36, Friston and Penny 30 used DCM for network discovery, to detect the dependence graph structure which best fits the observed fMRI data.

Figure 6.

Effective connectivity. Maximum a posteriori estimates of parameters measuring effective connectivity in an fMRI study on attention to motion (Stephan et al.113).

Classification and Prediction

Another important task in studies based on fMRI data is the ability to do classification or prediction. Some studies look at predicting individuals' brain activity. For example, the prediction of post-treatment brain activity may be of interest to clinicians as a guide to individualized treatment selection. Other studies consider the prediction of a clinical or a behavioral response.

For prediction of brain activity, Guo et al.46 developed a two-stage hierarchical Bayesian model using patient's pre-treatment scans of fMRI, in combination with other relevant patient characteristics, to predict the brain activity of the patient following a specific treatment. At the first-stage, the authors considered a GLM for the dependent variable with Yi1(υ) and Yi2(υ) the (T1 × 1) pre- and (T2 × 1) post-treatment serial BOLD responses for subject i, measured at voxel υ, which is given by

| (38) |

where are design matrices convolved with a HRF and are high-pass filtering matrices. At the second stage, the subject-specific effects Bij(υ), j = 1, 2 are modeled via a linear model with design matrix containing covariates including treatment assignment and other relevant patient characteristics, to capture the association between pre- and post-treatment neuroimaging measurements. Prediction is done via the conditional distribution of the post-treatment effects Bi2(υ) given the pre-treatment effects Bi1(υ). Derado et al.21 proposed an extension of the model of Bowman et al.6 that takes into account the spatial correlations between neighboring brain regions and intra-regional voxels in addition to capturing the temporal correlations between scans. Even though they applied the model in a study using positron emission tomography (PET) data, their proposed method is applicable to fMRI studies as well.

Linear regression models have been used for the prediction of clinical or behavioral outcomes based on fMRI data. Michel et al.85 developed a multiclass sparse Bayesian regression model, based on a clustering of the voxels, for the prediction of cognitive states. van Gerven et al.121 employed a Bayesian logistic regression model with a multivariate Laplace prior on the regression coefficients to predict experimental conditions (i.e., handwritten digits), based on BOLD response data. Morcom and Friston86 used a multivariate Bayesian model to infer which activity patterns predict memory formation.

Furthermore, scalar-on-image regression models of the type

| (39) |

with Y a n × 1 response variable (for instance, measurements of subjects' emotion) and X a n × p matrix of imaging-related predictors at p voxels, have recently attracted significant interest. Goldsmith et al.41 considered spike-and-slab priors on η, with an Ising prior on the selection indicator. Li et al.72 proposed priors of the type

| (40) |

to select voxels that are predictive of the subjects' response while simultaneously achieving clustering of similar regression coefficients.

Integrative Imaging

An important recent trend in the literature on fMRI data is the use of multi-modal techniques, that is, combining measurements originated from multiple imaging methods, to overcome the limitations when only one modality is used and to aid estimation and prediction13. Also, nowadays more and more studies look at collecting both imaging and genetics data on the same subjects, making it possible to develop statistical models that aim at linking neural activity across multiple individuals to their genetic information78,118. As patterns of brain connectivity in fMRI scans are known to be related to the subjects' genome, the ability to model the link between the imaging and genetic components could indeed lead to improved diagnostics and therapeutic interventions.

Multi-Modal Techniques

A number of Bayesian methods have been proposed for the integration of fMRI data with other neuroimaging techniques that provide information on the brain function or structure. Electroencephalography (EEG)89 is a functional neuroimaging technique that achieves a direct recording of the brain's electrical activity via multiple electrodes placed on the scalp that measure voltage fluctuations from ionic current flows within the brain's neurons. Magnetoencephalography (MEG)47 maps brain activity by measuring the magnetic fields resulting from electrical current in the brain via magnetic field sensors. Unlike fMRI, EEG and MEG have a very high temporal resolution (in the order of milliseconds) but poor spatial resolution. In addition, Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI)69 is a noninvasive magnetic resonance imaging technique that measures the diffusion of water in biological tissues to produce neural tract images of the brain in vivo, therefore capturing structural information. Clearly, the ability to combine neuroimaging techniques could enable researchers to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of the brain.

The complementary characteristics of temporal and spatial resolutions of EEG/MEG and fMRI techniques makes their integration highly desirable. Jorge et al.59 presented a review on integrative methods. Information from EEG/MEG data has been incorporated in some of the modeling approaches for fMRI data that we have previously described. For example, Kalus et al.61 extended the approach in Kalus et al.62 by using EEG-informed spatial priors in their Bayesian variable selection approach to detect brain activation. Specifically, they relate the prior activation probabilities to a latent predictor stage ζ = (ζ1, …, ζV)T via a probit link p(γυ = 1) = Φ(ζυ), with Φ the standard normal cdf and ζυ consisting of an intercept term and an EEG effect, that is

| (41) |

where Jυ, υ = 1, …, V is the continuous spatial EEG information and where 0, glob and flex indicate three types of predictors: predictor 0 contains a spatially-varying intercept ς0 = (ς0,1, …, ς0,V)T, and corresponds to an fMRI activation detection scheme without incorporating EEG information; predictor glob contains a global EEG effect ςG in addition to the intercept; predictor flex contains a spatially-varying EEG effect ς = (ς1, …, ςV)T. With an IGMRF, the priors of ς0 and ς are of the form in (16). Other approaches focus on incorporating information from fMRI into models for EEG/MEG data. A common approach to EEG/MEG data looks at source localization as an ill-posed inverse problem and uses other imaging techniques to determine prior information that impose constraints on source activity and locations18,52,60,81,95,104. Automatic Relevance Determination (ARD) priors on the variance of the source current at each source location were used by Sato et al.104, fMRI-based activity maps as priors on the source location by Phillips et al.95, Mattout et al.81 and Henson et al.52, exponential distribution as fMRI-based prior on the source locations by Jun et al.60. Babajani-Feremi et al.2 explored variational Bayesian expectation maximization methods for the estimation of the model parameters.

A truly joint model of EEG/MEG and event-related fMRI data was first proposed by Daunizeau et al.19. These authors consider a linear system of equations of the type

| (42) |

where M represents the p × t1 matrix of EEG data, with p the number of sensors and t1 the number of time points, G is a p × n matrix associated with the position and orientation of the dipoles, J is a n × t1 matrix of the unknown time courses of the dipoles, Y is the t2 × n matrix of voxel-wise fMRI data, with t2 the number of time points and n the number of voxels, h is the k×n matrix of unknown HRFs at each voxel and B is the t2 × k design matrix. The authors considered a finite parcellation of the cortical surface into q anatomically and functionally homogeneous regions, associating a time course to each region Pi (i = 1, …, q). They then defined a bioelectric event-related response for source J as

| 43 |

with X being an unknown q × t1 matrix of the q time courses, C the known n × q matrix describing the cortex parcelling (Cji = 1 if j ∈ Pi, and Cji = 0 otherwise), wEEG a n × 1 unknown vector describing the spatial profile of each active cortical source, and R a residual bioelectric activity. Similarly, they specify a hemodynamic event-related response of the type

| (44) |

with Z an unknown k × q matrix of the HRF temporal shape of the q regions, wfMRI an unknown n × 1 vector associated with the spatial profile of the hemodynamic activity sources and L a residual term. The author assume wEEG = wfMRI=w and specify priors for the cortical currents and the HRF, as well as spatial priors based on a spatial Laplacian on w. See also Ou et al.90 and Luessi et al.80 for extensions to more general and flexible prior models.

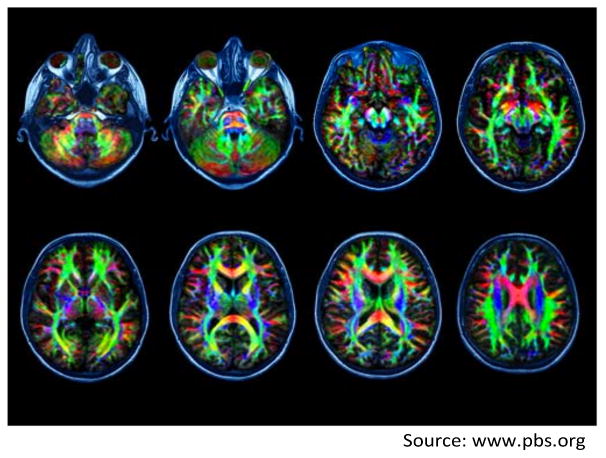

An interesting avenue for future research is the development of methods for the integration of fMRI and DTI data141. DTI is an MRI technique that provides information regarding the structure of white matter in the brain (see Figure 7). Axons, neuron fibers that serve as lines of transmission in the nervous system, form bundles of textured fibers in the white matter. This extensive system of white-matter bundles directly links some brain structures. DTI non-invasively maps these white-matter fiber tracts in the brain by measuring the diffusion of water molecules, therefore providing a measure of the so-called anatomical (or structural) connectivity, which refers to how different brain regions are physically connected. Many of the existing approaches to modeling functional connectivity by supplementing fMRI data with information from DTI data use frequentist models8,17,45, while Iyer et al.55 employ Bayesian networks informed by DTI data.

Figure 7.

Example of Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI) data.

Imaging Genetics

It is generally known that human brain mapping and connectivity can be affected by the individual's genetic characteristics. Studies that allow to investigate how particular subsets of polymorphisms can affect functional brain activity are of paramount importance. In addition, such studies could facilitate the identification of the genetic determinants of complex brain-related disorders such as autism, dementia and schizophrenia. Imaging genetics refers, in particular, to situation where structural and functional neuroimaging techniques are applied to study subjects carrying genetic risk variants that relate to a psychiatric disorder.

Recently proposed approaches for integrative analyses of fMRI and genetic data use frequentist methods, such as classical regression models or PCA-ICA dimension reduction techniques15,79,123. In the Bayesian literature, Stingo et al.114 proposed a hierarchical mixture model based on ROI summary measures of BOLD signal intensities measured on schizophrenic patients and healthy subjects. Their model incorporates spatial MRF priors for the selection of features (e.g. ROIs) that discriminate schizophrenic from healthy controls and mixture components that depend on selected covariates (e.g. single nucleotide polymorphisms - SNPs) measured on the individual subjects. Posterior inference results into the simultaneous selection of a set of discriminatory ROIs and the relevant SNPs, together with the reconstruction of the correlation structure of the selected regions. Salazar et al.102 proposed a joint model of ordered/categorical questionnaire data, fMRI and S NP data. Their approach aims at predicting questionnaire answers based on fMRI and SNP data and brain responses to external stimuli based on SNP data and answers to questionnaires.

Imaging genetic studies have great potential for the discovery of biomarkers implicated in brain functions and are expected to be the topic of much research in the future. One interesting area of research, for example, is the study of family data, in particular twin studies. With family data, the genetic similarity (on average) between the subjects within a family allows to infer the heritability of a phenotype. Even though this type of experimental design has been used primarily on structural data, some contributions also exist in fMRI studies, see for example Glahn et al.39 and van den Berg et al.120 for an early Bayesian model.

Conclusions

There has been a continued interest in the use of fMRI data, and this has motivated a very rapid development of statistical techniques for the analysis of such data. In this review paper we have focused on Bayesian methods. Unlike many of the classical inferential techniques, Bayesian models allow for flexibility, mainly via spatial and adaptive priors that can readily incorporate external information, and can be easily fitted via full MCMC or approximate computational techniques.

In this review paper we have divided methods according to the objective of the analysis. First, we have described spatio-temporal hierarchical models for the estimation of the task-related activation patterns. We have then addressed methods for functional and effective brain connectivity. We have also touched upon methods for prediction of a psychological condition or a treatment response and, finally, have presented a discussion of models that aim at combining multi-modal imaging techniques, particularly fMRI data with EEG/MEG and DTI data. We have also briefly discussed the emerging field of imaging genetics. The latter topics, on integrative models, are quite recent and certainly represent interesting avenues for further developments of Bayesian methodologies. Indeed, many more important contributions are to be expected by Bayesian statisticians working in the area of fMRI data analysis.

Throughout the paper we have highlighted that fMRI experiments produce massive amount of spatially and temporally correlated data, posing challenges to statistical analysis, for both classical and Bayesian procedures. Even though posterior inference can be often carried out via standard MCMC methods, the dimensionality of the data may limit the practical use of Bayesian methodologies. We have briefly discussed alternative posterior approximation methods, such as Variational Bayes, which drastically reduce the computation times. Further research is needed in the development of those estimation schemes, especially in order to accurately assess the trade-off between the gain in computation time and the precision of the resulting estimates. For example, while Variational Bayes methods may lead to good approximations of the posterior means, it is generally well-understood that they may underestimate the posterior variance and also poorly estimate the correlation structure of the data5,100.

Many software tools have been developed for fMRI data analysis. The most popular are FMRIB Software Library (FSL) http://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl, Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM) http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm, Analysis of Functional NeuroImages (AFNI) http://afni.nimh.nih.gov and Brain Voyager http://www.brainvoyager.com. Among those, both FSL and SPM include Bayesian methods. For example, the models of Friston et al.26, Penny et al.93,94 are implemented in SPM and the method of Woolrich et al.130 in FSL, allowing the option of either a full MCMC or a Variational Bayes algorithm for posterior inference. In SPM, for example, spatio-temporal models of type (1) can be fitted with priors as Unweighted Graph Laplacian (UGL), Weighted Graph Laplacian (WGL), Gaussian Markov Random Field (GMRF), etc, and with AR or independent error terms. A list of choices for the HRF are also available.

In spite of our best efforts, the coverage of Bayesian approaches for fMRI data analysis we have presented in this paper is, of course, not comprehensive. For example, we have not discussed meta-analysis, which is an important area in fMRI. Since multi-subject studies often have limited sample sizes, it is important to adopt strategies to determine whether task-related changes in brain activity, or networks of activated brain regions, are consistent across studies. Some of the recent methodological developments use Bayesian hierarchical models with spatial point processes63,64 and Bayesian nonparametric regression models136. Studies with larger sample sizes are also beginning to emerge, as the result of collaborative efforts among various teams of researchers.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the Editor and the three referees for their constructive comments. We also thank Brian Caffo, Vince Calhoun, Ciprian Crainiceanu, Ivor Cribben, Marco Ferreira, Nicole Lazar, Hernando Ombao and Hongtu Zhu for comments on an earlier version of this paper.

References

- 1.Andersen AH, Gash DM, Avison MJ. Principal component analysis of the dynamic response measured by fMRI: a generalized linear systems framework. Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 1999;17(6):795–815. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(99)00028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babajani-Feremi A, Bowyer S, Moran J, Elisevich K, Soltanian-Zadeh H. Variational Bayesian framework for estimating parameters of integrated E/MEG and fMRI model. SPIE Medical Imaging. 2009:72621T–72621T. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhattacharya S, Maitra R. A nonstationary nonparametric Bayesian approach to dynamically modeling effective connectivity in functional magnetic resonance imaging experiments. The Annals of Applied Statistics. 2011;5(2B):1183–1206. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhattacharya S, Ho M, Purkayastha S. A Bayesian approach to modeling dynamic effective connectivity with fMRI data. NeuroImage. 2006;30:794–812. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bishop CM. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning. Springer; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bowman F, Caffo B, Bassett S, Kilts C. A Bayesian hierarchical framework for spatial modeling of fMRI data. NeuroImage. 2008;39(1):146–156. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bowman FD. Brain imaging analysis. Annu Rev Stat Appl. 2014;1:61–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev-statistics-022513-115611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bowman FD, Zhang L, Derado G, Chen S. Determining functional connectivity using fMRI data with diffusion-based anatomical weighting. NeuroImage. 2012;62:1769–1779. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown PJ, Vannucci M, Fearn T. Multivariate Bayesian variable selection and prediction. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Statistical Methodology) 1998;60(3):627–641. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Büchel C, Friston KJ. Modulation of connectivity in visual pathways by attention: cortical interactions evaluated with structural equation modelling and fMRI. Cerebral Cortex. 1997;7(8):768–778. doi: 10.1093/cercor/7.8.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bullmore E, Fadili J, Maxim V, Şendur L, Whitcher B, Suckling J, Brammer M, Breakspear M. Wavelets and functional magnetic resonance imaging of the human brain. NeuroImage. 2004;23:234–249. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buxton R, Frank L. A model for the coupling between cerebral blood flow and oxygen metabolism during neural stimulation. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism. 1997;17(1):64–72. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199701000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calhoun VD, Lemieux L. Neuroimage: Special issue on multimodal data fusion. NeuroImage. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.04.070. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calhoun VD, Adali T, Pearlson GD, Pekar JJ. A method for making group inferences from functional MRI data using independent component analysis. Human Brain Mapping. 2001;14(3):140–151. doi: 10.1002/hbm.1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen J, Calhoun V, Pearlson G, Ehrlich S, Turner J, Ho B, Wassink T, Michael A, Liu J. Multifaceted genomic risk for brain function in schizophrenia. NeuroImage. 2012;61(4):866–875. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cribben I, Haraldsdottir R, Atlas LY, Wager TD, Lindquist MA. Dynamic connectivity regression: Determining state-related changes in brain connectivity. NeuroImage. 2012;61:907–920. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.03.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Damoiseaux JS, Greicius MD. Greater than the sum of its parts: a review of studies combining structural connectivity and resting-state functional connectivity. Brain Struct Funct. 2009;213:525–533. doi: 10.1007/s00429-009-0208-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Daunizeau J, Grova C, Mattout J, Marrelec G, Clonda D, Goulard B, Pélégrini-Issac M, Lina J, Benali H. Assessing the relevance of fMRI-based prior in the EEG inverse problem: a Bayesian model comparison approach. Signal Processing, IEEE Transactions on. 2005;53(9):3461–3472. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daunizeau J, Grova C, Marrelec G, Mattout J, Jbabdi S, Pélégrini-Issac M, Lina J, Benali H. Symmetrical event-related EEG/fMRI information fusion in a variational Bayesian framework. NeuroImage. 2007;36(1):69–87. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daunizeau J, Friston KJ, Kiebel S. Variational Bayesian identification and prediction of stochastic nonlinear dynamic causal models. Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena. 2009;238(21):2089–2118. doi: 10.1016/j.physd.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Derado G, Bowman FD, Zhang L. Predicting brain activity using a Bayesian spatial model. Statistical methods in medical research. 2013;22(4):382–397. doi: 10.1177/0962280212448972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fadili MJ, Bullmore ET. Wavelet-generalised least squares: A new BLU estimator of linear regression models with 1/f errors. NeuroImage. 2002;15:217–232. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferguson TS. A Bayesian analysis of some nonparametric problems. The Annals of Statistics. 1973;1(2):209–230. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Flandin G, Penny W. Bayesian fMRI data analysis with sparse spatial basis function priors. NeuroImage. 2007;34(3):1108–1125. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Friston K. Causal modelling and brain connectivity in functional magnetic resonance imaging. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e33. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Friston K, Penny W, Phillips C, Kiebel S, Hinton G, Ashburner J. Classical and Bayesian inference in neuroimaging: Theory. NeuroImage. 2002;16:465–483. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Friston KJ. Functional and effective connectivity in neuroimaging: a synthesis. Human Brain Mapping. 1994;2:56–78. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Friston KJ. Functional and effective connectivity: a review. Brain Connectivity. 2011;1(1):13–36. doi: 10.1089/brain.2011.0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Friston KJ, Penny W. Posterior probability maps and SPMs. NeuroImage. 2003;19(3):1240–1249. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00144-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Friston KJ, Penny W. Post hoc Bayesian model selection. NeuroImage. 2011;56(4):2089–2099. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.03.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Friston KJ, Jezzard P, Turner R. Analysis of functional MRI time-series. Human Brain Mapping. 1994;1(2):153–171. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Friston KJ, Holmes AP, Poline JB, Grasby PJ, Williams SCR, Frackowiak RSJ, Turner R. Analysis of fMRI time-series revisited. NeuroImage. 1995;2(1):45–53. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1995.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Friston KJ, Fletcher P, Josephs O, Holmes A, Rugg MD, Turner R. Event-related fMRI: characterizing differential responses. NeuroImage. 1998;7(1):30–40. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1997.0306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Friston KJ, Mechelli A, Turner E, Price CJ. Nonlinear responses in fMRI: the Balloon model, Volterra kernels and other hemodynamics. NeuroImage. 2000;9:416–429. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Friston KJ, Harrison L, Penny W. Dynamic causal modelling. NeuroImage. 2003;19(4):1273–1302. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00202-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Friston KJ, Li B, Daunizeau J, Stephan K. Network discovery with DCM. NeuroImage. 2011;56(3):1202–1221. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.12.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Genovese CR. A Bayesian time-course model for functional magnetic resonance imaging data. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2000;95(451):691–703. [Google Scholar]

- 38.George EI, McCulloch RE. Approaches for Bayesian variable selection. Statistica Sinica. 1997;7(2):339–373. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Glahn DC, Winkler AM, Kochunov P, Almasy L, Duggirala R, Carless MA, Curran JC, Olvera RL, Laird AR, Smith SM. Genetic control over the resting brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107(3):1223–1228. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909969107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goebel R, Roebroeck A, Kim D, Formisano E. Investigating directed cortical interactions in time-resolved fMRI data using vector autoregressive modeling and Granger causality mapping. Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2003;21(10):1251–1261. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2003.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goldsmith J, Huang L, Crainiceanu CM. Smooth scalar-on-image regression via spatial Bayesian variable selection. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics. 2014;23(1):46–64. doi: 10.1080/10618600.2012.743437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gorrostieta C, Fiecas M, Ombao H, Burke E, Cramer S. Hierarchical vector auto-regressive models and their applications to multi-subject effective connectivity. Frontiers in Computational Neuroscience. 2013;7 doi: 10.3389/fncom.2013.00159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gössl C, Auer D, Fahrmeir L. Bayesian spatio-temporal inference in functional magnetic resonance imaging. Biometrics. 2001;57(2):554–562. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2001.00554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Granger C. Investigating causal relations by econometric models and cross-spectral methods. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society. 1969:424–438. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Greicius MD, Supekar K, Menon V, Dougherty RF. Resting-state functional connectivity reflects structural connectivity in the default mode network. Cerebral Cortex. 2009;19:72–78. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guo Y, Bowman FD, Kilts C. Predicting the brain response to treatment using a Bayesian hierarchical model with application to a study of schizophrenia. Human Brain Mapping. 2008;29(9):1092–1109. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hämäläinen M, Hari R, Ilmoniemi RJ, Knuutila J, Lounasmaa OV. Magnetoencephalography—theory, instrumentation, and applications to non-invasive studies of the working human brain. Reviews of Modern Physics. 1993;65(2):413–497. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harrison L, Green G. A Bayesian spatiotemporal model for very large data sets. NeuroImage. 2010;50(3):1126–1141. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harrison L, Penny W, Friston KJ. Multivariate autoregressive modeling of fMRI time series. NeuroImage. 2003;19(4):1477–1491. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00160-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harrison L, Penny W, Daunizeau J, Friston KJ. Diffusion-based spatial priors for functional magnetic resonance images. NeuroImage. 2008;41(2):408–423. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Havlicek M, Jan J, Brazdil M, Calhoun VD. Dynamic Granger causality based on Kalman filter for evaluation of functional network connectivity in fMRI data. NeuroImage. 2010;53:65–77. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.05.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Henson R, Flandin G, Friston KJ, Mattout J. A parametric empirical Bayesian framework for fMRI-constrained MEG/EEG source reconstruction. Human Brain Mapping. 2010;31(10):1512–1531. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Holmes AP, Friston KJ. Generalisability, random effects & population inference. NeuroImage. 1998;7:S754. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huettel SA, Song AW, McCarthy G. Functional magnetic resonance imaging. Vol. 1. Sinauer Associates Sunderland; MA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Iyer SP, Shafran I, Grayson D, Gates K, Nigg JT, Fair DA. Inferring functional connectivity in MRI using Bayesian network structure learning with a modified PC algorithm. NeuroImage. 2013;75:165–175. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.02.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jbabdi S, Woolrich M, Behrens T. Multiple-subjects connectivity-based parcellation using hierarchical Dirichlet process mixture models. NeuroImage. 2009;44(2):373–384. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jeong J, Vannucci M, Ko K. A wavelet-based Bayesian approach to regression models with long memory errors and its application to fMRI data. Biometrics. 2013;69:184–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2012.01819.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Johnson T, Liu Z, Bartsch A, Nichols T. A Bayesian non-parametric Potts model with application to pre-surgical fMRI data. Statistical Methods in Medical Research. 2013;22(4):364–381. doi: 10.1177/0962280212448970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jorge J, van der Zwaag W, Figueiredo P. EEG-fMRI integration for the study of human brain function. NeuroImage. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.05.114. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jun S, George J, Kim W, Paré-Blagoev J, Plis S, Ranken D, Schmidt D. Bayesian brain source imaging based on combined MEG/EEG and fMRI using MCMC. NeuroImage. 2008;40(4):1581–1594. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kalus S, Sämann P, Czisch M, Fahrmeir L. Technical Report 146. University of Munich; 2013. fMRI activation detection with EEG priors. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kalus S, Sämann P, Fahrmeir L. Classification of brain activation via spatial Bayesian variable selection in fMRI regression. Advances in Data Analysis and Classification. 2013:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kang J, Johnson TD, Nichols TE, Wager TD. Meta analysis of functional neuroimaging data via Bayesian spatial point processes. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2011;106(493):124–134. doi: 10.1198/jasa.2011.ap09735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kang J, Nichols TE, Wager TD, Johnson TD. A Bayesian hierarchical spatial point process model for multi-type neuroimaging meta analysis. 2014 doi: 10.1214/14-aoas757. Submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kim D, Burge J, Lane T, Pearlson G, Kiehl K, Calhoun VD. Hybrid ICA-Bayesian network approach reveals distinct effective connectivity differences in schizophrenia. NeuroImage. 2008;42(4):1560–1568. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.05.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kim S, Smyth P, Stern H. A nonparametric Bayesian approach to detecting spatial activation patterns in fMRI data. Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2006. 2006:217–224. doi: 10.1007/11866763_27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lange N, Zeger SL. Non-linear Fourier time series analysis for human brain mapping by functional magnetic resonance imaging. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series C (Applied Statistics) 1997;46(1):1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lazar NA. The statistical analysis of functional MRI data. Springer; New York: 2008. Statistics for Biology and Health. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Le Bihan D, Mangin J, Poupon C, Clark C, Pappata S, Molko N, Chabriat H. Diffusion tensor imaging: concepts and applications. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2001;13(4):534–546. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lee K, Jones GL, Caffo BS, Bassett SS. Spatial Bayesian variable selection models on functional magnetic resonance imaging time-series data. Bayesian Analysis. 2014;9(3):699–732. doi: 10.1214/14-BA873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li B, Daunizeau J, Stephan K, Penny W, Hu D, Friston KJ. Generalised filtering and stochastic DCM for fMRI. NeuroImage. 2011;58(2):442–457. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.01.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li F, Zhang T, Wang Q, Gonzalez MZ, Maresh EL, Coan J. Spatial Bayesian variable selection and grouping in high-dimensional scalar-on-image regressions. 2014 Submitted. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Li J, Wang Z, Palmer S, McKeown M. Dynamic Bayesian network modeling of fMRI: a comparison of group-analysis methods. NeuroImage. 2008;41(2):398–407. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.01.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Li R, Chen K, Fleisher A, Reiman E, Yao L, Wu X. Large-scale directional connections among multi resting-state neural networks in human brain: a functional MRI and Bayesian network modeling study. NeuroImage. 2011;56(3):1035–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li R, Wu X, Chen K, Fleisher A, Reiman E, Yao L. Alterations of directional connectivity among resting-state networks in Alzheimer disease. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 2012;34(2):340–345. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lindquist M. The statistical analysis of fMRI data. Statistical Science. 2008;23(4):439–464. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lindquist M, Wager T. Validity and power in hemodynamic response modeling: a comparison study and a new approach. Hum Brain Mapping. 2007;28(8):764–784. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Liu J, Calhoun VD. A review of multivariate analyses in imaging genetics. Frontiers in Neuroinformatics. 2014;8 doi: 10.3389/fninf.2014.00029. Article 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Liu J, Pearlson G, Windemuth A, Ruano G, Perrone-Bizzozero N, Calhoun V. Combining fMRI and SNP data to investigate connections between brain function and genetics using parallel ICA. Human Brain Mapping. 2009;30(1):241–255. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Luessi M, Babacan S, Molina R, Booth J, Katsaggelos A. Bayesian symmetrical EEG/fMRI fusion with spatially adaptive priors. NeuroImage. 2011;55(1):113–132. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.11.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mattout J, Phillips C, Penny W, Rugg M, Friston KJ. MEG source localization under multiple constraints: an extended Bayesian framework. NeuroImage. 2006;30(3):753–767. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.McKeown M, Makeig S, Brown G, Jung T, Kindermann S, Bell A, Sejnowski T. Analysis of fMRI data by blind separation into independent spatial components. Human Brain Mapping. 1998;6:160–188. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0193(1998)6:3<160::AID-HBM5>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mclntosh A, Gonzalez-Lima F. Structural equation modeling and its application to network analysis in functional brain imaging. Human Brain Mapping. 1994;2(1):2–22. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Meyer FG. Wavelet-based estimation of a semiparametric generalized linear model of fMRI time-series. IEEE transactions on Medical Imaging. 2003;22(3):315–322. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2003.809587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Michel V, Eger E, Keribin C, Thirion B. Multiclass sparse Bayesian regression for fMRI-based prediction. Journal of Biomedical Imaging. 2011:2–14. doi: 10.1155/2011/350838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Morcom A, Friston KJ. Decoding episodic memory in ageing: a Bayesian analysis of activity patterns predicting memory. NeuroImage. 2012;59(2):1772–1782. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.08.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Müller P, Parmigiani G, Rice K. FDR and Bayesian multiple comparisons rules. In: Bernardo JM, Bayarri MJ, Berger JO, Dawid AP, Heckerman AFM, Smith D, West M, editors. Bayesian Statistics 8. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]