Abstract

Objective

To establish cultures of epithelial cells from all regions of the human epididymis to provide reagents for molecular approaches to functional studies of this epithelium.

Design

Experimental laboratory study.

Setting

University research institute.

Patient(s)

Epididymis from seven patients undergoing orchiectomy for suspected testicular cancer without epididymal involvement.

Intervention(s)

Human epididymis epithelial cells harvested from adult epididymis tissue.

Main Outcome Measure(s)

Establishment of a robust culture protocol for adult human epididymal epithelial cells.

Result(s)

Cultures of caput, corpus, and cauda epithelial cells were established from epididymis tissue of seven donors. Cells were passaged up to eight times and maintained differentiation markers. They were also cryopreserved and recovered successfully. Androgen receptor, clusterin, and cysteine-rich secretory protein 1 were expressed in cultured cells, as shown by means of immunofluorescence, Western blot, and quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). The distribution of other epididymis markers was also shown by means of qRT-PCR. Cultures developed transepithelial resistance (TER), which was androgen responsive in the caput but androgen insensitive in the corpus and cauda, where unstimulated TER values were much higher.

Conclusion(s)

The results demonstrate a robust in vitro culture system for differentiated epithelial cell types in the caput, corpus, and cauda of the human epididymis. These cells will be a valuable resource for molecular analysis of epididymis epithelial function, which has a pivotal role in male fertility.

Keywords: Epididymis epithelial cell culture: caput, corpus, cauda

The biologic functions of the epididymis are critical for normal spermatozoa maturation, because it is during their passage through this organ that spermatozoa acquire full motility and fertility. The three anatomic segments of the epidid-ymis, the caput (head), corpus (body), and cauda (tail), have distinct roles: The caput and corpus are crucial for the early and late processes of spermatozoa maturation, and the cauda serves as a storage site for functionally mature spermatozoa.

The major cell types within the epididymis epithelium are similar along the length of the organ and include principal cells, clear cells, basal cells, and narrow cells, among others (1).However, cells within each region have distinct functions and a unique proteome. Studies of region-specific epididymal proteins show that certain cell types can express quite different subsets of genes, which contributes to the different physiologic functions of the segments (2–4). The different protein expression signatures along the epididymis are controlled by particular transcription factor networks that coordinate region-specific functions (5, 6). These regulatory mechanisms within the caput, corpus, and cauda of the epididymis establish critical sequential changes in epididymis luminal environment, which are required for normal sperm maturation and thence male fertility.

Although a few critical proteins are well studied in the human epididymis epithelium (7–9), there are few genome-wide data sets that adequately describe the transcriptional profile of these cells (5, 10, 11). Moreover, most relevant data derive from tissue segments, rather than isolated epithelial cells, thus complicating the analysis. The epithelial cell layer responds to hormonal and other biologic signals from underlying tissue, blood supply, and the luminal fluid, so it has been argued that these need to be studied together (12). However, many of these stimuli can be mimicked during culture in vitro, and only the pure epithelial cell populations can generate robust data on their differentiated function. Microarray analyses of epididymis tissues of different animal species revealed segment- or region-specific gene expression patterns (13–17), but the function and relevance to epididymis biology of many of these genes is unknown. Primary cultures of epididymis epithelial cells from mice (18) and rats (19–21) generated valuable information on the expression profiles of these cells. However, many genes show different expression patterns in human and rodent epididymis (22, 23), as do several major epididymal secreted proteins (3). In addition, human epididymal tissue has structural and morphologic characteristics that are distinct from other species (24). This species-specific variation necessitates the use of human primary epididymal epithelial (HEE) cells to understand the molecular basis of human epididymis function in health and disease.

Adult HEE cell cultures were established from epididymal fragments, generating small numbers of primary cells (25, 26). However, in-depth studies of epididymis epithelial function by genome-wide approaches currently require more than one million cells per experiment, and many functional studies necessitate cultured cells with a phenotype that is stable over several generations. We previously used cultures of immature HEE cells to map open chromatin genome wide and identified candidate transcriptional networks coordinating gene expression in the epididymis (5). However, because these HEE cells are immature (27) they are unlikely to exhibit all aspects of the differentiated adult human epididymis. To circumvent this limitation, our goal was to test the hypothesis that establishment of equivalent cultures of adult HEE cells would provide suitable reagents to study differentiated functions of the mature HEE. Here we describe a robust method of culturing adult HEE cells on plastic substrates that enables multiple passages before cells lose morphologic and functional differentiation. Cells were cultured separately from the caput, corpus, and cauda regions. Moreover, sufficient numbers of cells retaining specialized epithelial features were generated to enable detailed molecular analysis. These cultures, which are phenotypically characterized here by means of immunocytochemistry, Western blot, and quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR), will be valuable for the study of regional special functions of the human epididymis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of Primary Cultures

Human epididymis tissue was obtained with Institutional Review Board approval from seven patients (age range 2236 years) undergoing inguinal radical orchiectomy for a clinical diagnosis of testicular cancer. None of the epididymides had extension of the testicular cancer, and all were freshly placed into normal saline solution until further processing.

Adult HEE cultures were established with the use of methods described previously for immature HEE cells (27) with modification. Epididymal tissue was placed in Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS), and fat and connective tissue were removed with the use of a pair of Vannas spring scissors and fine forceps under a dissecting microscope. The three different anatomic regions, caput, corpus, and cauda, were separated. Tissues of each segment were cut into 2–3-mm pieces and placed into a 50-mL centrifuge tube with 10-mL digestion buffer containing 150 U/mL collagenase type I, 15 μg/mL DNAse I (both from Worthington) and 0.5 mmol/L Ca2+ in HBSS. Samples were incubated for 2 hours at 37°C in a water bath (shaking every 10–15 min) and with gentle pipetting several times with a 5-mL serologic pipette after 1 hour. The digestion buffer was collected after 1 hour and replaced with fresh buffer for the second 1 hour period. The cell suspensions from the first digestion and the entire second digestion mixture were passed through a 360-μm stainless mesh and then pelleted by centrifugation at 200g for 5 minutes. Pri-maria flasks (BD Bioscience) coated with type I collagen (1:75; Purecol 5005-B) were used. The adult HEE cells were grown in CMRL 1066 medium (containing 15% fetal calf serum [FCS], 2 mmol/L L-glutamine, 1 μg/mL hydrocortisone, 0.2 U/mL insulin, and 10−10 mol/L cholera toxin). In the 1st week of culture, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 0.25 μg/mL amphotericin B were added to the culture medium. Subsequently, cells were cultured in media without these additives and maintained in a humid 5% CO2 incubator at 33°C.

The cells were examined every other day with the use of an inverted phase-contrast microscope (Leica DMIL), and photographs were taken with the use of a digital camera (Leica FCD280). Culture medium was changed every 3 days. The adult HEEs were passaged with trypsin EDTA (0.25% trypsin, 0.53 mmol/L EDTA) before they reached 80% confluence, and the trypsin activity was inhibited with 0.1% soybean trypsin inhibitor.

For cryopreservation, cells were resuspended in fetal bovine serum (FBS) to a concentration of 6 × 106 cells/mL, and mixed with an equal volume of FBS with 10% dimethyl-sulfoxide. Cryovials containing 1-mL aliquots of cell suspension were then frozen by means of standard protocols and stored in liquid nitrogen. For recovery, the cells were thawed rapidly with the use of standard methods and placed on collagen I–coated tissue culture flasks. Cell viability was >95%.

For experiments on androgen receptor (AR)–mediated pathways, cultures were grown in phenol red-free CMRL 1066 medium containing 15% charcoal stripped FCS with the other supplements described above for at least 3 days before treatment with 200 nmol/L testosterone (Sigma T1500) or 1 nmol/L methyltrienolone (R1881; Perkin Elmer NLP0050) for 12–16 hours.

Immunocytochemistry

Epididymal and epithelial markers reported previously in the literature, including cysteine-rich secretory protein 1 (CRISP1), clusterin, AR, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), and cytokeratin 8 (CK8) (22, 28–30) were examined in this study. Primary adult HEEs were grown to confluence on 12-mm circular glass coverslips and fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes. The cells were then permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 15 minutes, followed by blocking in 1% bovine serum albumin for 30 minutes before immunocytochemistry. Antibodies used were to CRISP1 (1:100; Sigma HPA028445), clusterin (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology SC166907), cytokeratin 8 (1:400; Thermo Fisher Scientific PA532469), AR (1:300; Santa Cruz SC816), and CFTR (1:300; Cystic Fibrosis Foundation #570). Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated antirabbit IgG or Alexa Fluor 549 conjugated antimouse IgG (Jackson Immunoresearch) was used as the secondary antibody. Cells were counterstained with 6-diamino-2-phenylindole (Life Technologies) and mounted with the use of Fluorsave (Calbiochem). Samples were then analyzed with the use of a Leica DMR microscope or a Zeiss 510 Meta confocal laser scanning microscope.

Quantitative Reverse-Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction

The qRT-PCR was performed by means of standard protocols. Briefly, cDNA was synthesized with the use of a Taqman Reverse Transcription reagents kit (Applied Biosystems) with random hexamers, and qPCR experiments were carried out with Sybr Green master mixes. The sequences of the primer pairs specific for each target gene and the reaction conditions are listed in Supplemental Table 1 (available online at www.fertstert.org).

Western Blotting

Cells were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer containing 1% (vol/vol) protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma). Crude lysates were separated on denaturing sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Western blots were probed by means of standard methods with the use of a horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibody and visualized with the use of the electrochemiluminescence Western blotting substrate (Thermo Scientific).

Transepithelial Resistance Measurements

To evaluate the effect of androgen on the transepithelial resistance (TER) of adult HEEs, cells were grown on filter inserts with 0.4-μm pore size (BD Biosciences). Cultures were monitored daily by measurement of TER with the use of an EVOM2 epithelial voltohmmeter (World Precision Instruments). When the TER reached 70–75 ohm-cm2, the cultures were treated with testosterone or R1881, as above. After each TER measurement, the culture medium was replaced with fresh medium with or without androgen.

Statistical Analyses

Student t test was used to compare the results for the treated samples with those for the corresponding control samples. Statistical analyses were performed with the use of Prism software (Graphpad).

RESULTS

Characteristics of the Cultured Adult HEE Cells

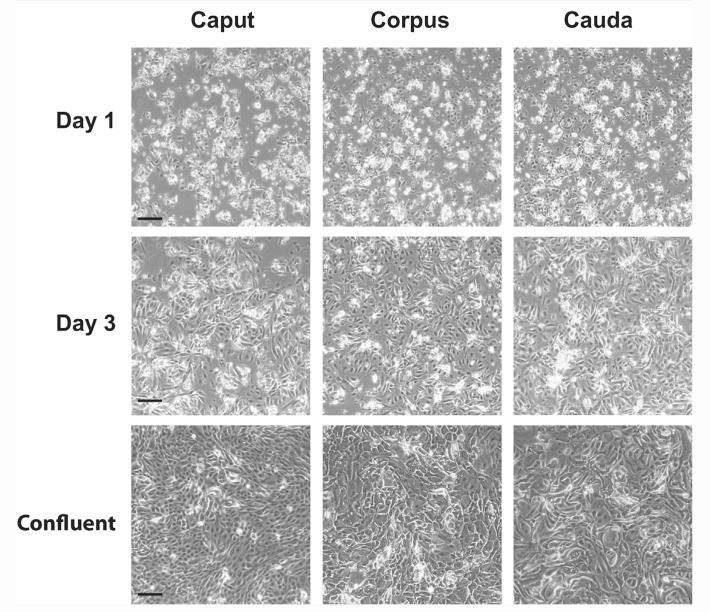

Adult HEE cells isolated from adult human epididymis were initially present as sphere-like clumps and single cells adhering to the substrate within 24 hours of plating. After 48 hours, the clumps of cells gradually flattened and spread into a monolayer, giving the appearance of a colony-like growth configuration (Fig. 1). Compared with adult HEEs from caput, initial cultures from corpus or cauda contained a greater numbers of large cells, though their identity was not yet known. Caput cultures reached confluence within 5 days when plated at a cell density of 3–5 × 104 cells/cm2, and the cells could be passaged with trypsin (0.25%)/EDTA (0.53 mmol/L) at least 8–10 times (at a 1:8 passage ratio) before showing increased numbers of enlarged and irregularly shaped cells. From an initial 6–8 × 106 caput cells at P0 confluence, up to 5 × 1014 cells were obtained at P8 confluence. In contrast, the corpus and cauda cultures required a high density of initial seeding, 6–10 × 104 cells/cm2 (at a 1:3 or 1:4 passage ratio), and required 7 days to become confluent. After 4–5 passages (from an initial P0 of 2–3 × 106 cells), the adult HEEs from the corpus and cauda often showed an increased cell size with abundant cytoplasmic vacuoles indicative of senescence (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Phase-contrast imaging of adult human caput, corpus, and cauda primary cells in culture (scale bar = 100 μm). (Top) One day after plating on collagen-coated plastic substrate. (Middle) By 3 days after plating, the cells flattened and started to grow as a monolayer. (Bottom) Cells at confluence.

Leir. Human epididymis epithelial cell cultures. Fertil Steril 2014.

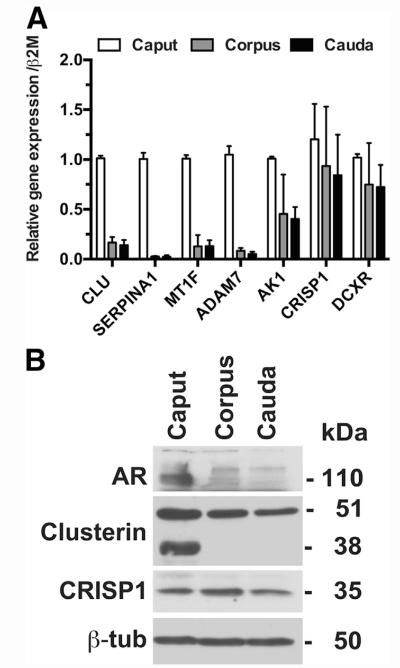

Epididymal Markers

Next, we used cellular markers to establish, first, the unique protein expression signature of the epithelial cells cultured from the caput, corpus, and cauda, and second, to determine which differentiated markers were lost when cells were removed from the intact organs. Further characterization of the epididymal cultured cell population was performed by means of qRT-PCR (Fig. 2A), Western blot (Fig. 2B), and immunostaining (Fig. 3). Seven markers that were previously associated with epididymis function (22, 31–37) were first evaluated by means of qRT-PCR with the use of RNA extracted from caput, corpus, or cauda HEE cell cultures (Fig. 2A). These included clusterin (CLU), serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade A, member 1 (SERPINA1), metal regulatory factor 1 (MTF1), ADAM metallopeptidase domain 7 (ADAM7), adenylate kinase 1 (AK1), CRISP1, and dicarbonyl/L-xylulose reductase (DCXR). CLU, SERPINA1, MTF1, and ADAM7 showed much higher mRNA expression levels in caput cells than in corpus and cauda cells. AK1 mRNA expression in the caput was about twice the level seen in the corpus and cauda, whereas CRISP1 and DCXR showed similar expression levels in all three cell types.

FIGURE 2.

Regional gene and protein expression of epididymal markers in primary human epididymis epithelial cells from caput, corpus, and cauda. (A) Gene expression: total RNA extracted from cultures at passage 3 or 4 from caput, corpus, and cauda. Quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction was performed with the use of Sybr Green with primers for the genes shown. Data are combined from cultures from two independent sets of tissue samples and are normalized to β2-microglobulin. (B) Protein expression: cell lysates separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Western blots probed with antibodies specific for androgen receptor (AR), clusterin, and cysteine-rich secretory protein 1 (CRISP1). β-Tubulin provided the loading control.

Leir. Human epididymis epithelial cell cultures. Fertil Steril 2014.

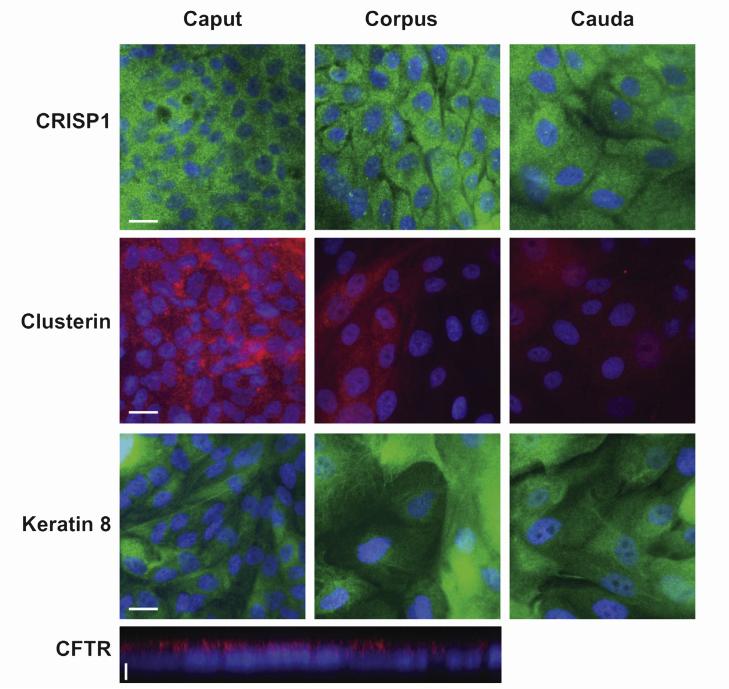

FIGURE 3.

Cysteine-rich secretory protein 1 (CRISP1), clusterin, cytokeratin 8 (scale bar = 20 μm), and cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR; scale bar = 5 μm) expressed in primary human epididymis epithelial cells. Immunofluorescence with the use of specific antibodies as shown in caput, corpus, and cauda cells. Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated antirabbit IgG (green) or Alexa Fluor 549–conjugated antimouse IgG (red) was used as the secondary antibody. Cells were counterstained with 6-diamino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). CFTR in polarized caput cells is shown by means of confocal imaging.

Leir. Human epididymis epithelial cell cultures. Fertil Steril 2014.

The CLU and CRISP1 mRNA data were confirmed by Western blot (Fig. 2B), where CRISP1 was seen in HEE cells from all regions. In contrast, two forms of clusterin were evident: a 50-kDa form present in caput, corpus, and cauda cells, and a 38-kDa form restricted to caput cells though not evident in all cultures. Also shown in Figure 2B is AR, which has very low abundance in the corpus and cauda HEE cells in contrast to much higher levels in caput cells. Immunofluorescent detection of CRISP1 and clusterin expression in HEE cells from all three regions is shown in Figure 3 and was consistent with the Western blot data. CRISP1 was expressed in cells from caput, corpus, and cauda, whereas clusterin is more abundant in the caput HEE cells. As expected, CK8 was seen in a fibrillar cytoplasmic distribution in all cells, and the CFTR protein was particularly evident on the apical surface of polarized caput cells. In general, the cells prepared from the corpus and cauda were larger than those derived from the caput.

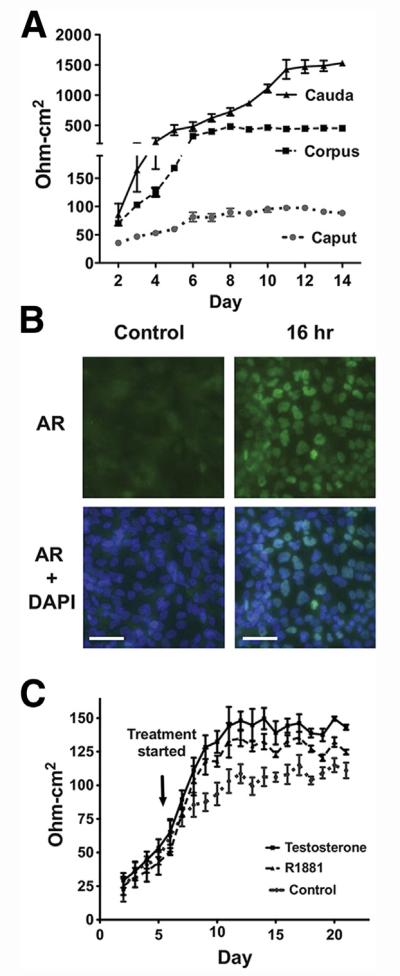

Transepithelial Resistance of the HEE Polarized Cultures

Adult HEE cells were grown on permeable filter membrane supports to form polarized epithelial layers, enabling tight junction integrity to be measured. In the absence of testosterone or R1881 treatment, the TER of the caput cultures remained relatively constant: ~80 ohm-cm2 after 10 days. In contrast, the corpus and cauda cultures reached TER values of ~400 and ~1,500 ohm-cm2, respectively, after day 7 (Fig. 4A). Next, to determine the effect of androgens on TER, because these are known to play a critical role in epididymis epithelial function in vivo, we first showed that HEE caput cells were responsive to AR agonists. R1881 treatment for 12–16 hours at 1 nm was shown to activate AR expression and its translocation to the nucleus (Fig. 4B; 16 h). Exposure of caput cells to testosterone (200 nmol/L) or R1881 (1 nmol/L) caused a significant increase (P< .05) in the TER of these cultures. A maximum TER of 120–140 ohm-cm2 (Fig. 4C) was reached ~6 days after the start of hormone stimulation. With the use of a semiphysiologic concentration of 200 nmol/L testosterone or 1 nmol/L R1881 treatment, caput cells exposed to testosterone showed ~15% higher TER than the cells with R1881 treatment.

FIGURE 4.

Effects of testosterone and R1881 on the transepithelial resistance (TER) of human epididymal epithelial cultures. (A) TER measurements in caput, corpus, and cauda cells cultured on membrane filter supports. (B) Immunofluorescence of androgen receptor (AR) in primary caput HEE cells treated with R1881 for 16 hours. R1881 treatment induced AR relocation from the cytoplasm to the nucleus. 6-Diamino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) was used for nuclear counterstaining (scale bar = 50 μm). (C) Effects of testosterone and R1881 on the maintenance of the tight junction permeability barrier of the caput. The resistance was multiplied by the effective growth area of the filter (~0.31 cm2) to yield the area resistance (ohm-cm2). The net value of the TER was computed by subtracting the background. n = 3; representative experiment shown.

Leir. Human epididymis epithelial cell cultures. Fertil Steril 2014.

DISCUSSION

We have described a robust method to isolate and culture adult HEE cells from human epididymis tissue. The primary cells derived from caput tissue were cultured for 7–8 passages and those from corpus and cauda for 4–5 passages without showing signs of senescence. HEE cells were cultured at 33°C because that is similar to physiologic conditions. Earlier analysis of canine HEEs cultured at 37°C demonstrated a specific down-regulation of CE5 mRNA expression compared with culture at 33°C (38). CE5 is the equivalent of the human CD52/HE5 major sperm surface antigen. In another study of boar HEE cells, the morphologic characteristics of cells cultured at 32°C and 37°C were equivalent except that cells grew faster at 37°C (39). Further advantages of the 33°C maintenance temperature were that epithelial cells were predominant in the culture and the lower temperature appeared to select against fibroblasts, which grow more slowly at 33°C than at 37°C. To further enhance adherence and favorable conditions for HEE cells, culture substrates were coated with collagen I.

Several methods to culture HEE cells from epididymal fragments were reported previously (25, 26, 40). In those cases, most of the connective tissue surrounding the epididymal tubules was removed and aggregates of enzyme-digested epididymal tissue were plated on plastic substrates. The HEEs cultured in that way retain a structure similar to their original architecture and morphology. Although the cultures can grow for a long period of time (42 days [40] or 56 ± 28 days [26]), the cells tend to take longer to become confluent. Adult HEE cells from corpus were also cultured for several passages in another study (41). Here we have shown that when the primary cells from caput, corpus, or cauda were prepared as small cell clumps, the HEEs adhered faster, and not only could they be passaged multiple times, they were also successfully cryopreserved. Frozen cells had good viability after thawing and maintained their differentiated characteristics.

Segment-specific expression of epididymal epithelial markers were retained in the cultures, with the caput HEE cells exhibiting higher expression of clusterin whereas CRISP1 expression was equivalent in caput, corpus, and cauda cells. CRISP1 binds to the postacrosomal region of the sperm head, where it plays a role in sperm-egg fusion (42). CRISP1 is regulated by androgens and other testicular factors (43, 44). Clusterin may provide the sperm surface with a protective coat, guarding them against nonspecific proteases, glycosidases, or other injurious agents (33, 36). We also examined regional expression of a number of additional markers that were previously reported to be associated with epididymis function (22). qRT-PCR showed caput-selective expression of SERPINA1 and MTF1 consistent with earlier data on human epididymis tissue (22). In rodent epididymis, several SERPIN domain–containing genes were associated with sperm maturation and fertility processes (32, 37). ADAM7, which may participate in the sperm-egg interaction (35), was also abundant only in the caput HEE cells. In contrast, DCXR, which encodes an epididymal-originating acrosomal sperm protein known to be involved in sperm–zona pellucida interaction (31, 34), was expressed at similar levels in cells from all three regions of the epididymis. MTF1 belongs to a family of cytosolic stress response proteins that are modulated by androgens and show segment specific androgen-dependent expression at the mRNA level (45). AK1 is localized in the flagella of mouse sperm and is proposed to play a role in sperm motility control (46). Although DCXR and ADAM7 were shown to be corpus-specific in an earlier analysis of epididymal tissue (22), the present data suggest either variability between individuals or a difference in cultured HEE cells compared with whole tissue.

Androgen receptor was expressed in HEE cells from all regions, although it was more abundant in caput HEE cells. Androgen regulation is known to be important for epididymal development and maintaining the normal functions of the epididymis (8, 47). Several studies have shown that the testosterone level in the human epididymis is ~40 ng/g wet tissue and the dihydrotestosterone level is 10–20 ng/g wet tissue (48–50). In addition, there were no significant concentration differences along the epididymal fractions of the caput, corpus, and cauda. Testosterone controls the expression of tight junction components that form the blood-testis barrier in the testis (51, 52). Immortalized human epididymis epithelial cell cultures form tight junctions, with an increase in the TER across the cell monolayer, which can reach ~140 ohm-cm2 when cultured with 5 nmol/L testosterone in the medium (53). Here we saw that caput HEE cultures generate a TER of 70–90 ohm-cm2 in the absence of added androgens. However, the TER increased to 130–140 ohm-cm2 when caput cells were grown in testosterone or R1881. Interestingly, the corpus and cauda HEE cultures had much higher TERs of ~ 1,500 ohm-cm2 without androgens and showed no increase in TER when treated with testosterone or R1881. These data suggest that tight junctions in the caput are androgen regulated, although those in the corpus and cauda are androgen independent. The high TER in the later segments might be related to their function of active fluid absorption to further concentrate the spermatozoa. Of note, when grown on permeable supports the HEE cells maintained high TER for more than 1 month.

A significant hurdle in advancing molecular studies on the adult human epididymis epithelium has been a shortage of cell culture models. Recently, human epididymal cell lines were generated from caput and corpus tissues (53). These lines have considerable value in circumventing the limited prolifer-ative capacity of primary cells. However, the primary adult HEE cultures described here maintain more of the cellular diversity of the intact epithelium and recapitulate its normal differentiated properties. These cells provide a robust resource for elucidating the transcriptional networks that coordinate functions of epididymis epithelium, and for studying biologic mechanisms relevant to its health and disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01HD068901 to A.H.) and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (Harris11G0 to A.H.).

Footnotes

S.-H.L. has nothing to disclose. J.A.B. has nothing to disclose. S.E.E. has nothing to disclose. A.H. has nothing to disclose.

Discuss: You can discuss this article with its authors and with other ASRM members at http://fertstertforum.com/eirsh-epididymis-epithelial-cell-culture/

Use your smartphone to scan this QR code and connect to the discussion forum for this article now.*

* Download a free QR code scanner by searching for “QR scanner” in your smartphone’s app store or app marketplace.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shum WW, da Silva N, Brown D, Breton S. Regulation of luminal acidification in the male reproductive tract via cell-cell crosstalk. J Exp Biol. 2009;212:1753–61. doi: 10.1242/jeb.027284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cornwall GA, von Horsten HH. Sperm Maturation in the epididymis. In: Carrell DT, editor. The genetics of male infertility. Humana Press; Totowa, New Jersey: 2007. pp. 211–31. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dacheux JL, Dacheux F. Protein secretion in the epididymis. In: Robaire B, Hinton BT, editors. The epididymis: from molecules to clinical practice. Springer; New York: 2002. pp. 151–68. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cornwall GA, Lareyre JJ, Matusik RI, Hinton BT, Orgebin-Crist MC. Gene expression and epididymal function. In: Robaire B, Hinton BT, editors. The epididymis: from molecules to clinical practice. Springer; New York: 2002. pp. 169–200. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bischof JM, Gillen AE, Song L, Gosalia N, London D, Furey TS, et al. A genome-wide analysis of open chromatin in human epididymis epithelial cells reveals candidate regulatory elements for genes coordinating epididymal function. Biol Reprod. 2013;89:104. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.113.110403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Browne JA, Yang R, Leir SH, Song L, Crawford GE, Harris A. Open chromatin mapping identifies transcriptional networks regulating human epididymis epithelial function. Mol Hum Reprod. 2014;20:1198–207. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gau075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cornwall GA. New insights into epididymal biology and function. Hum Reprod Update. 2009;15:213–27. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmn055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arrotéia KF, Garcia PV, Barbieri MF, Justino ML, Pereira L. The epididymis: embryology, structure, function and its role in fertilization and infertility. In: Pereira L, editor. Embryology–updates and highlights on classic topics. Intech; Rijeka: 2012. pp. 41–66. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dacheux JL, Dacheux F. New insights into epididymal function in relation to sperm maturation. Reproduction. 2014;147:R27–42. doi: 10.1530/REP-13-0420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang JS, Liu Q, Li YM, Hall SH, French FS, Zhang YL. Genome-wide profiling of segmental-regulated transcriptomes in human epididymis using oligo microarray. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2006;250:169–77. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2005.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu S, Yao G, Guan X, Ni Z, Ma W, Wilson EM, et al. Research resource: genome-wide mapping of in vivo androgen receptor binding sites in mouse epididymis. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24:2392–405. doi: 10.1210/me.2010-0226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chauvin TR, Griswold MD. Androgen-regulated genes in the murine epididymis. Biol Reprod. 2004;71:560–9. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.026302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dubé E, Chan PT, Hermo L, Cyr DG. Gene expression profiling and its relevance to the blood-epididymal barrier in the human epididymis. Biol Reprod. 2007;76:1034–44. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.106.059246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnston DS, Jelinsky SA, Bang HJ, DiCandeloro P, Wilson E, Kopf GS, et al. The mouse epididymal transcriptome: transcriptional profiling of segmental gene expression in the epididymis. Biol Reprod. 2005;73:404–13. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.039719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnston DS, Turner TT, Finger JN, Owtscharuk TL, Kopf GS, Jelinsky SA. Identification of epididymis-specific transcripts in the mouse and rat by transcriptional profiling. Asian J Androl. 2007;9:522–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7262.2007.00317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jelinsky SA, Turner TT, Bang HJ, Finger JN, Solarz MK, Wilson E, et al. The rat epididymal transcriptome: comparison of segmental gene expression in the rat and mouse epididymides. Biol Reprod. 2007;76:561–70. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.106.057323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guyonnet B, Marot G, Dacheux JL, Mercat MJ, Schwob S, Jaffrezic F, et al. The adult boar testicular and epididymal transcriptomes. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:369. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carballada R, Saling PM. Regulation of mouse epididymal epithelium in vitro by androgens, temperature and fibroblasts. J Reprod Fertil. 1997;110:171–81. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.1100171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klinefelter GR, Amann RP. Isolation of principal cells and basal cells by elutriation of suspensions of rat epididymal tissue. Int J Androl. 1980;3:287–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.1980.tb00119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown DV, Amann RP, Wagley LM. Influence of rete testis fluid on the metabolism of testosterone by cultured principal cells isolated from the proximal or distal caput of the rat epididymis. Biol Reprod. 1983;28:1257–68. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod28.5.1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Byers SW, Citi S, Anderson JM, Hoxter B. Polarized functions and permeability properties of rat epididymal epithelial cells in vitro. J Reprod Fertil. 1992;95:385–96. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0950385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thimon V, Koukoui O, Calvo E, Sullivan R. Region-specific gene expression profiling along the human epididymis. Mol Hum Reprod. 2007;13:691–704. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gam051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jalkanen J, Kotimaki M, Huhtaniemi I, Poutanen M. Novel epididymal protease inhibitors with Kazal or WAP family domain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;349:245–54. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Turner TT. On the epididymis and its role in the development of the fertile ejaculate. J Androl. 1995;16:292–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moore HD, Curry MR, Penfold LM, Pryor JP. The culture of human epididymal epithelium and in vitro maturation of epididymal spermatozoa. Fertil Steril. 1992;58:776–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akhondi MA, Chapple C, Moore HD. Prolonged survival of human spermatozoa when co-incubated with epididymal cell cultures. Hum Reprod. 1997;12:514–22. doi: 10.1093/humrep/12.3.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harris A, Coleman L. Ductal epithelial cells cultured from human foetal epididymis and vas deferens: relevance to sterility in cystic fibrosis. J Cell Sci. 1989;92(Pt 4):687–90. doi: 10.1242/jcs.92.4.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harris A, Chalkley G, Goodman S, Coleman L. Expression of the cystic fibrosis gene in human development. Development. 1991;113:305–10. doi: 10.1242/dev.113.1.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Bryan MK, Mallidis C, Murphy BF, Baker HW. Immunohistological localization of clusterin in the male genital tract in humans and marmosets. Biol Reprod. 1994;50:502–9. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod50.3.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ungefroren H, Ivell R, Ergun S. Region-specific expression of the androgen receptor in the human epididymis. Mol Hum Reprod. 1997;3:933–40. doi: 10.1093/molehr/3.11.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boué F, Bérubé B, de Lamirande E, Gagnon C, Sullivan R. Human sperm-zona pellucida interaction is inhibited by an antiserum against a hamster sperm protein. Biol Reprod. 1994;51:577–87. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod51.4.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu ZH, Liu Q, Shang Q, Zheng M, Yang J, Zhang YL. Identification and characterization of a new member of Serpin family–HongrES1 in rat epididymis. Cell Res. 2002;12:407–10. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Law GL, Griswold MD. Activity and form of sulfated glycoprotein 2 (clusterin) from cultured Sertoli cells, testis, and epididymis of the rat. Biol Reprod. 1994;50:669–79. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod50.3.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Légaré C, Gaudreault C, St-Jacques S, Sullivan R. P34H sperm protein is preferentially expressed by the human corpus epididymidis. Endocrinology. 1999;140:3318–27. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.7.6791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin YC, Sun GH, Lee YM, Guo YW, Liu HW. Cloning and characterization of a complementary DNA encoding a human epididymis-associated disintegrin and metalloprotease 7 protein. Biol Reprod. 2001;65:944–50. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod65.3.944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mattmueller DR, Hinton BT. In vivo secretion and association of clusterin (SGP-2) in luminal fluid with spermatozoa in the rat testis and epididymis. Mol Reprod Dev. 1991;30:62–9. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1080300109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamazaki K, Adachi T, Sato K, Yanagisawa Y, Fukata H, Seki N, et al. Identification and characterization of novel and unknown mouse epididymis-specific genes by complementary DNA microarray technology. Biol Reprod. 2006;75:462–8. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.048058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pera I, Ivell R, Kirchhoff C. Body temperature (37°C) specifically down-regulates the messenger ribonucleic acid for the major sperm surface antigen CD52 in epididymal cell culture. Endocrinology. 1996;137:4451–9. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.10.8828507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bassols J, Kadar E, Briz M, Pinart E, Sancho S, Garcia-Gil N, et al. Effect of culture conditions on the obtention of boar epididymal epithelial cell monolayers. Anim Reprod Sci. 2006;95:262–72. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cooper TG, Yeung CH, Meyer R, Schulze H. Maintenance of human epididymal epithelial cell function in monolayer culture. J Reprod Fertil. 1990;90:81–91. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0900081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sun GH, Liu HW, Lin YC, Yu DS, Chang SY. Identification of maturation-related wheat-germ lectin-binding proteins in the culture of human corpus epididymal epithelial cells. Arch Androl. 2000;45:53–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ellerman DA, Cohen DJ, Da Ros VG, Morgenfeld MM, Busso D, Cuasnicu PS. Sperm protein “DE” mediates gamete fusion through an evolutionarily conserved site of the CRISP family. Dev Biol. 2006;297:228–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haendler B, Habenicht UF, Schwidetzky U, Schuttke I, Schleuning WD. Differential androgen regulation of the murine genes for cysteine-rich secretory proteins (CRISP) Eur J Biochem. 1997;250:440–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.0440a.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Turner TT, Bomgardner D. On the regulation of Crisp-1 mRNA expression and protein secretion by luminal factors presented in vivo by microperfusion of the rat proximal caput epididymidis. Mol Reprod Dev. 2002;61:437–44. doi: 10.1002/mrd.10115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cyr DG, Dufresne J, Pillet S, Alfieri TJ, Hermo L. Expression and regulation of metallothioneins in the rat epididymis. J Androl. 2001;22:124–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cao W, Haig-Ladewig L, Gerton GL, Moss SB. Adenylate kinases 1 and 2 are part of the accessory structures in the mouse sperm flagellum. Biol Reprod. 2006;75:492–500. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.106.053512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brooks DE. Epididymal functions and their hormonal regulation. Aust J Biol Sci. 1983;36:205–21. doi: 10.1071/bi9830205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bidlingmaier F, Dorr HG, Eisenmenger W, Kuhnle U, Knorr D. Testosterone and androstenedione concentrations in human testis and epididymis during the first two years of life. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1983;57:311–5. doi: 10.1210/jcem-57-2-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Suescun MO, Campo S, Rivarola MA, Gonzalez-Echeverria F, Scorticati C, Ghirlanda J, et al. Testosterone, dihydrotestosterone, and zinc concentrations in human testis and epididymis. Arch Androl. 1981;7:297–303. doi: 10.3109/01485018108999321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leinonen P, Hammond GL, Vihko R. Testosterone and some of its precursors and metabolites in the human epididymis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1980;51:423–8. doi: 10.1210/jcem-51-3-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meng J, Holdcraft RW, Shima JE, Griswold MD, Braun RE. Androgens regulate the permeability of the blood-testis barrier. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:16696–700. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506084102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yan HH, Mruk DD, Lee WM, Cheng CY. Blood-testis barrier dynamics are regulated by testosterone and cytokines via their differential effects on the kinetics of protein endocytosis and recycling in Sertoli cells. FASEB J. 2008;22:1945–59. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-070342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dubé E, Dufresne J, Chan PT, Hermo L, Cyr DG. Assessing the role of claudins in maintaining the integrity of epididymal tight junctions using novel human epididymal cell lines. Biol Reprod. 2010;82:1119–28. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.109.083196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.