Abstract

Objective

We sought to assess the relationship between a short interpregnancy interval (IPI) following a pregnancy loss and subsequent live birth and pregnancy outcomes.

Study Design

A secondary analysis of women enrolled in the Effects of Aspirin in Gestation and Reproduction trial with an hCG-positive pregnancy test and whose last reproductive outcome was a loss were included in this analysis (n=677). IPI was defined as the time between last pregnancy loss and last menstrual period of the current pregnancy and categorized by 3-month intervals. Pregnancy outcomes include live birth, pregnancy loss, and any pregnancy complications. These were compared between IPI groups using multivariate relative risk estimation by Poisson regression.

Results

Demographic characteristics were similar between IPI groups. The mean gestational age of prior pregnancy loss was 8.6 ± 2.8 weeks. The overall live birth rate was 76.5%, with similar live birth rates between those with IPI ≤ 3 months as compared to IPI > 3 months, aRR=1.07 (95% CI 0.98–1.16). Rates were also similar for peri-implantation loss (aRR=0.95; 95% CI 0.51–1.80), clinically confirmed loss, (aRR=0.75; 95% CI 0.51–1.10), and any pregnancy complication (aRR=0.88; 95% CI 0.71–1.09) for those with IPI ≤ 3 months as compared to IPI > 3 months.

Conclusion

Live birth rates and adverse pregnancy outcomes, including pregnancy loss, were not associated with a very short IPI after a prior pregnancy loss. The traditional recommendation to wait at least 3 months after a pregnancy loss before attempting a new pregnancy may not be warranted.

Keywords: interpregnancy interval, miscarriage, pregnancy loss, pregnancy outcomes, spontaneous abortion

Introduction

Pregnancy loss is the most frequent complication of early pregnancy (most commonly occurring prior to 10 weeks gestation) and affects approximately 12–15% of clinically recognized pregnancies.1,2 After a pregnancy loss, couples often seek counseling on how long they should wait before attempting to conceive. The length of delay is of particular concern for women who may be sub-fertile or who are over 35 years of age.

Most studies addressing interpregnancy interval (IPI) concentrate on the interval between live births and subsequent pregnancies. There is considerable evidence that an IPI less than 18 months after a term or preterm delivery is associated with an increased risk for poor maternal and perinatal outcome.3–6 However, there is significant controversy as to what the optimal timing is for the next pregnancy following a pregnancy loss.

It is common practice for obstetricians to recommend waiting at least 3 months before attempting a new pregnancy after an early pregnancy loss,7 while the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends a minimum IPI of at least 6 months after a spontaneous or elective abortion.8,9 However, there are few data to support these recommendations and contemporary studies demonstrate an inverse relationship between the rate of live birth and increasing IPI.10–13 Furthermore, published studies consist mostly of retrospective studies without uniformity in documentation of gestational age and outcomes, and the majority do not address very short IPI (less than 3 months).9–12 Thus, our primary objective was to assess the relationship between the interval between pregnancy loss and subsequent live birth in a large cohort of women, recruited from multiple clinical centers in the United States, who were actively trying to conceive following a pregnancy loss. Our secondary objective was explore the relationship between IPI and subsequent pregnancy complications including peri-implantation and clinical loss, preterm birth, preeclampsia, and gestational diabetes.

Materials and Methods

This study is a secondary data analysis of women enrolled in the Effects of Aspirin in Gestation and Reproduction (EAGeR) trial. The EAGeR trial, a block-randomized, multi-center, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial of preconception low-dose aspirin or placebo, enrolled 1228 women, aged 18–40, with a history of one to two pregnancy losses. Details of the study design and protocol have been published previously.14 Women were stratified by eligibility criteria. The “original” eligibility stratum, included women actively trying to conceive with a history of only one prior pregnancy loss at <20 weeks’ gestation during the past year, up to one prior live birth, up to one elective termination/ectopic pregnancy, regular menstrual cycles of 21–42 days in length during the preceding 12 months, no history of diagnosed or treated infertility and aged 18 to 40 years. Women in the “expanded” stratum included women who had one or two pregnancy losses, including those at >20 weeks’ gestation, with pregnancy losses occurring more than one year prior to enrollment, and with up to two prior live births. All other criteria were identical between the two strata. Of note, 14 women withdrew immediately following randomization and were excluded from further analysis because they contributed no observed follow-up time.

The trial was conducted at four clinical sites in the United States with recruitment between 2007 and 2011. Women were followed for up to six menstrual cycles while trying to conceive and through delivery if they became pregnant. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at each site, with each site serving as the IRB designated by the National Institutes of Health under a reliance agreement. All participants gave written informed consent prior to randomization.

Medical records were obtained documenting at least one of the up to two prior pregnancy losses with hCG, ultrasound, and/or histology. Each woman underwent an extensive questionnaire at baseline regarding her medical and obstetric history. Medical records were abstracted by trained study personnel. The majority of women (n=653, 96.5%) had a medically documented date of last loss. For the remaining 24 women (3.5%), we relied on their self-reported date of last loss. Similarly, the majority of women (n=589, 87.0%) had a medically documented gestational age of last loss, with an additional 86 women having a self-reported gestational age of loss.

Data for this study assessing interpregnancy interval and pregnancy outcomes were limited to women whose last reproductive outcome was a pregnancy loss (n=1074/1214, 88.5%) and subsequently became pregnant (n=677/1214, 55.8%). Pregnancy was ascertained by a urine pregnancy test (clinic and/or home with the majority [89%] having both) and confirmed by a 6–7 week ultrasound. IPI was defined as the time between previous loss and the last menstrual period of the confirmed pregnancy. IPI was categorized by 3-month intervals (0 to 3 months, > 3 to 6 months, > 6 to 9 months, > 9 to 12 months, and > 12 months).

The primary outcome was live birth. Secondary outcomes included pregnancy loss, types of pregnancy loss,15 and obstetric complications (preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, and preterm birth < 37 weeks). Peri-implantation loss was defined as a pregnancy loss before 5 weeks with no gestational sac visible on ultrasound. Pre-embryonic loss was defined as a pregnancy loss at 5 0/7 to 5 6/7 weeks with visible gestational sac and/or yolk sac, but no visible embryo on ultrasound. Embryonic loss was defined as a pregnancy loss at 6 0/7 to 9 6/7 weeks of an embryo with crown rump length (CRL) < 10mm and no visible cardiac activity on ultrasound. Fetal loss was defined as a pregnancy loss at 10 0/7- 19 6/7 weeks with documented fetal cardiac activity at or beyond 10 weeks (CRL ≥ 30mm) or passage of conceptus with CRL measuring at least 30mm. Stillbirth was defined as a pregnancy loss of a fetus at ≥ 20 weeks gestation without signs of life at the time of delivery. Clinically confirmed loss was defined as any stillbirth, preembryonic, embryonic, fetal loss, or other (including ectopic pregnancy). Preeclampsia was defined as having a systolic pressure ≥ 140 mmHg and/or diastolic pressure ≥ 90 mmHg that does not antedate the pregnancy and presents after 20 weeks gestation on ≥ 2 occasions at least 4 hours apart and proteinuria ≥ 0.3 grams in a 24-hour urine specimen or 1+ on dipstick.16 Preterm birth was defined as any delivery prior to 37 weeks (including spontaneous and medically indicated preterm births).

Participant demographic, lifestyle, and reproductive history characteristics between IPI intervals were compared using chi-squared or where appropriate Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables, and ANOVA for continuous variables. Multivariable Poisson regression with robust error variance (to correctly estimate the standard error) was used to assess the relative risk (RR) of live birth, peri-implantation loss, clinical loss, or pregnancy complication by IPI category (0–3, > 6–9, > 9–12, and > 12 versus reference of > 3–6 months; and ≤ 3 months versus reference of > 3 months).17,18 Models adjusted for potential confounders that were selected a priori and included factors known to be associated with IPI and pregnancy or live birth success, and not on the causal pathway. Final models were adjusted for maternal age, race, BMI, eligibility stratum, and gestational age of last loss. We compared results to models that additionally adjusted for self-reported months trying to achieve most recent pregnancy to adjust for potential undiagnosed and untreated subfertility. We conducted several sensitivity analyses including additionally adjusting for treatment group (e.g., aspirin or placebo), intercourse frequency in the prior 12 months, and additional demographic, lifestyle or reproductive history characteristics. As much of the literature makes comparisons between an IPI of ≤ 6 months versus a longer IPI, we also estimated the relative risks for live birth, pregnancy loss, and any pregnancy complication for women with an IPI ≤ 6 months versus > 6 months along with assessing differences in very short IPI (0–1, > 1–2, and > 2–3 months).

Results

Of the 677 women who became pregnant and whose last reproductive outcome was a pregnancy loss, 2.7% of women became pregnant within the first month, 33.2% became pregnant within 3 months and 65.7% became pregnant within 6 months. The median IPI was 4.3 months (inter-quartile range [IQR]: 2.6–7.4 months) and the median time from most recent pregnancy loss to study entry was 13.8 weeks (IQR: 7.4–31.0 weeks). There were no significant differences among IPI categories for demographic and lifestyle characteristics (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic, lifestyle, and reproductive history by interpregnancy interval

| Characteristics | Interpregnancy interval | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total n=677 | 0–3mo (n = 225) 33.2% |

3–6mo (n = 220) 32.5% |

6–9mo (n = 118) 17.4% |

9–12mo (n = 37) 5.5% |

>12 mo (n = 77) 11.4% |

P-value | |

| Demographics & Lifestyle | |||||||

| Age (mean ± SD) | 28.6 ± 4.6 | 28.5 ± 4.4 | 28.9 ± 4.8 | 28.4 ± 4.6 | 28.8 ± 5.0 | 28.5 ± 4.6 | 0.84 |

| BMI (mean ± SD) | 25.4 ± 6.1 | 25.1 ± 5.8 | 25 ± 6.3 | 25.9 ± 5.7 | 25.6 ± 6.3 | 26.6 ± 7.0 | 0.30 |

| Race (n [%]) | 0.21 | ||||||

| White | 657 (97.0) | 218 (96.9) | 216 (98.2) | 116 (98.3) | 35 (94.6) | 72 (93.5) | |

| Non-White | 20 (3.0) | 7 (3.1) | 4 (1.8) | 2 (1.7) | 2 (5.4) | 5 (6.5) | |

| Education (n [%]) | 0.12 | ||||||

| > High School | 607 (90.0) | 201 (89.3) | 204 (92.7) | 107 (90.7) | 31 (83.8) | 64 (83.1) | |

| ≤ High School | 70 (10.3) | 24 (10.7) | 16 (7.3) | 11 (9.3) | 6 (16.2) | 13 (16.9) | |

| LDA Treatment (n [%]) | 351 (51.9) | 118 (52.4) | 114 (51.8) | 56 (47.5) | 19 (51.4) | 44 (57.1) | 0.77 |

| Smoking in past year (n [%]) | 0.81 | ||||||

| Never | 604 (89.8) | 206 (92.4) | 193 (88.1) | 106 (90.6) | 33 (89.2) | 66 (85.7) | |

| Sometimes (<6 times/week) | 48 (7.1) | 13 (5.8) | 18 (8.2) | 7 (6) | 3 (8.1) | 7 (9.1) | |

| Daily | 21 (3.1) | 4 (1.8) | 8 (3.7) | 4 (3.4) | 1 (2.7) | 4 (5.2) | |

| Alcohol consumption in past year (n [%]) | 0.35 | ||||||

| Never | 454 (67.8) | 160 (71.4) | 139 (64.1) | 82 (70.1) | 21 (58.3) | 52 (68.4) | |

| Sometimes | 199 (29.7) | 62 (27.7) | 69 (31.8) | 31 (26.5) | 14 (38.9) | 23 (30.3) | |

| Often | 17 (2.5) | 2 (0.9) | 9 (4.2) | 4 (3.4) | 1 (2.8) | 1 (1.3) | |

| Physical Activity (n [%]) | 1.00 | ||||||

| Low | 171 (25.3) | 60 (26.7) | 53 (24.1) | 31 (26.3) | 10 (27.0) | 17 (22.1) | |

| Moderate | 287 (42.4) | 94 (41.8) | 93 (42.3) | 50 (42.4) | 15 (40.5) | 35 (45.5) | |

| High | 219 (32.4) | 71 (31.6) | 74 (33.6) | 37 (31.4) | 12 (32.4) | 25 (32.5) | |

| Reproductive History | |||||||

| Previous Live Births (n [%]) | 0.01 | ||||||

| 0 | 304 (44.9) | 82 (36.4) | 93 (42.3) | 63 (53.4) | 22 (59.5) | 44 (57.1) | |

| 1 | 260 (38.4) | 104 (46.2) | 84 (38.2) | 40 (33.9) | 10 (27.0) | 22 (28.6) | |

| 2 | 113 (16.7) | 39 (17.3) | 43 (19.6) | 15 (12.7) | 5 (13.5) | 11 (14.3) | |

| Number of Previous Pregnancy Losses (n [%]) | 0.72 | ||||||

| 1 | 436 (64.4) | 147 (65.3) | 144 (65.5) | 74 (62.7) | 26 (70.3) | 45 (58.4) | |

| 2 | 241 (35.6) | 78 (34.7) | 76 (34.6) | 44 (37.3) | 11 (29.7) | 32 (41.6) | |

| Gestational agea of previous loss (n[%]) | 0.05 | ||||||

| < 8 weeks | 293 (43.4) | 101 (45.1) | 92 (41.8) | 44 (37.3) | 17 (46.0) | 39 (51.3) | |

| 8–13 weeks | 347 (51.4) | 118 (52.7) | 112 (50.9) | 67 (56.8) | 20 (54.1) | 30 (39.5) | |

| 14–19 weeks | 35 (5.2) | 5 (2.2) | 16 (7.3) | 7 (5.9) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (9.2) | |

| Gestational age of prior lossb | 8.6 ± 2.8 | 8.3 ± 2.5 | 8.7 ± 3 | 9.2 ± 3 | 8.1 ± 2.4 | 8.2 ± 3.1 | 0.07 |

| D & C performed on prior loss (n [%]) | 230 (34.0) | 77 (34.2) | 75 (34.1) | 44 (37.3) | 13 (35.1) | 21 (27.3) | 0.71 |

| Eligibility criteria (n [%]) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Original | 344 (50.8) | 118 (52.4) | 119 (54.1) | 67 (56.8) | 22 (59.5) | 18 (23.4) | |

| Expanded | 333 (49.2) | 107 (47.6) | 101 (45.9) | 51 (43.2) | 15 (40.5) | 59 (76.6) | |

| Months trying for most recent pregnancy (mean ± SD) | 4.3 ± 4.9 | 3.6 ± 4.6 | 3.9 ± 3.9 | 4.4 ± 4.2 | 5.8 ± 6 | 6.8 ± 7.3 | <0.001 |

| Ever tried for more than 12 months to become pregnant (n [%]) | 31 (4.7) | 7 (3.1) | 7 (3.2) | 6 (5.1) | 2 (5.7) | 9 (12.2) | 0.01 |

| Intercourse in the past 12 months (n [%]) | 0.44 | ||||||

| 3–6 times/week or more | 226 (34.0) | 78 (35.3) | 74 (34.4) | 35 (29.9) | 11 (30.6) | 28 (36.8) | |

| 1–2 times/week | 329 (49.5) | 106 (48) | 109 (50.7) | 62 (53) | 22 (61.1) | 30 (39.5) | |

| 2–3 times/month or less | 110 (16.5) | 37 (16.7) | 32 (14.9) | 20 (17.1) | 3 (8.3) | 18 (23.7) | |

Analyses performed via chi-square or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and analysis of variance or Kruskel-Walis for continuous variables. Study population includes women with one to two previous pregnancy losses enrolled in the EAGeR trial (2007–2011), whose last reproductive outcome was a pregnancy loss and subsequently became pregnant (n=677).

n=675; 589 documented (continuous) and 86 self-report (categorical <8 weeks, 8–13 weeks, and 14–19 weeks).

n=589 with documented loss recorded continuously (self-report assessed categorically <8 weeks, 8–13 weeks, and 14–19 weeks).

All women had a previous pregnancy loss prior to 19 weeks, with a mean gestational age of loss at 8.6 ± 2.8 weeks (range 2–19 weeks). Thirty-five women (5.2%) had a previous pregnancy loss between 14 and 19 weeks. Reproductive histories stratified by IPI group are shown in Table 1. Rates of dilation and curettage in the previous pregnancy were similar for the different IPI groups. The number of previous pregnancy losses was similar among IPI ≤ 3 months versus > 3 months as well as individual 3 month IPI groups. Groups differed slightly regarding prior live births with relatively fewer nulliparous women with an IPI < 3 months.

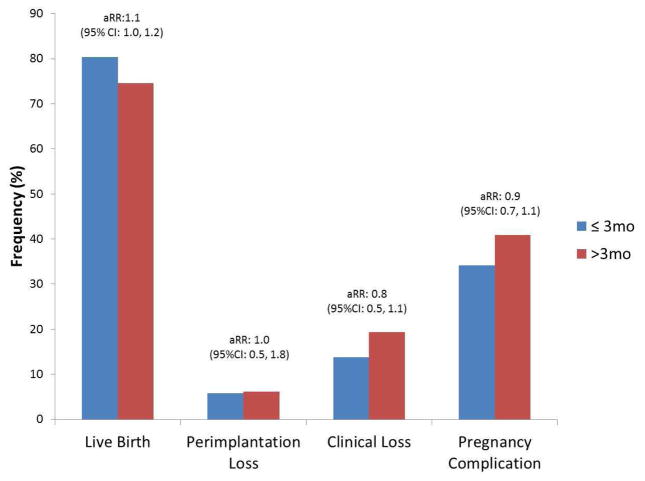

The overall live birth rate in our cohort was 76.5% (518/677). Live birth rates for IPI ≤ 3 months versus > 3 months were 80.4% (181/225) and 74.6% (337/452), respectively (Table 2). After adjustment for age, race, BMI, eligibility criteria, gestational age of previous loss, and months tried to conceive for most recent pregnancy, there was no significant difference in rate of achieving a live birth for IPI ≤ 3 months as compared to > 3 months, aRR=1.07 (95% CI, 0.98–1.16) (illustrated in Figure 1). A finer breakdown of IPI categories by 3-month intervals demonstrated highest live birth rates for the 0–3 month IPI (80.4%) with the lowest occurring in the > 12 month IPI group (65.0%). However, there were no statistically significant differences in live birth rates between 0–3, > 6–9, > 9–12, and > 12 month IPI groups compared to the reference of > 3–6 months. Live birth rates remained similar when the 0–3 month IPI group was further broken down by one month intervals, with 83.3%, 85.9% and 76.2% achieving a live birth for 0–1 month, > 1–2 month, and > 2–3 month IPI groups respectively.

Table 2.

Incidence of achieving live birth according to interpregnancy interval (n=677 women)

| Relative Risk (95% Confidence Interval) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Interpregnancy interval | Live Birth/Total n (%) | Model 1 | P-valuea | Model 2 | P-valueb |

| 0–3 mo | 181/225 (80.4) | 1.1 (1–1.2) | 0.32 | 1.0 (0.9–1.2) | 0.37 |

| 3–6mo | 168/220 (76.4) | REF | na | REF | na |

| 6–9mo | 91/118 (77.1) | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 0.86 | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 0.86 |

| 9–12mo | 28/37 (75.7) | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | 0.95 | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | 0.95 |

| >12mo | 50/77 (64.9) | 0.9 (0.7–1.0) | 0.09 | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 0.09 |

|

| |||||

| ≤ 3 months vs. >3 months | 181/225 (80.4) vs. 337/452 (74.6) | 1.1 (1.0–1.2) | 0.09 | 1.1 (1.0–1.2) | 0.15 |

Analyses performed via multivariate relative risk (RR) estimation by Poisson regression with robust error variance. Study population includes women with one to two previous pregnancy losses enrolled in the EAGeR trial (2007–2011), whose last reproductive outcome was a pregnancy loss and subsequently became pregnant (n=677).

Model 1: Adjusted for age, race, BMI, eligibility criteria, and gestational age of prior loss.

Model 2: Adjusted for age, race, BMI, eligibility criteria, gestational age of prior loss, and months tried to conceive for most recent pregnancy.

Figure 1. Pregnancy outcomes for women with an interpregnancy interval ≤ 3 months versus > 3 months.

1 Adjusted for age, race, BMI, eligibility criteria, gestational age of prior loss, and months tried to conceive for most recent pregnancy.

The average gestational age of a pregnancy loss that occurred during the trial was 9.9 ± 4.1 wks (Table 3). The most common type of loss was embryonic (53.4%) followed by pre-embryonic (27.1%), fetal (6.8%), and stillbirths (3.0%). These were similar for the different IPI groups compared to the reference of > 3–6 months, with the exception of a greater risk for peri-implantation failure among women with an IPI > 12 versus > 3–6 month IPI (aRR=3.70, [95% CI: 1.49–9.19]) after adjusting for age, race, BMI, eligibility criteria, gestational age of prior loss, and months tried to conceive for most recent pregnancy (Table 4). The risk of a clinically confirmed loss, however, remained similar between the different 3-month IPI groups.

Table 3.

Secondary obstetric outcomes according to interpregnancy interval (n=677 women)

| Characteristics | Interpregnancy interval | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total n=677 | 0–3mo (n = 225) 33.2% |

3–6mo (n = 220) 32.5% |

6–9mo (n = 118) 17.4% |

9–12mo (n = 37) 5.5% |

>12 mo (n = 77) 11.4% |

P-value | |

| Preterm birtha | 42 (8.1) | 12 (6.6) | 15 (8.9) | 8 (8.8) | 4 (14.3) | 3 (6.0) | 0.65 |

| Peri-implantation Loss (n [%]) | 41 (6.0) | 13 (5.8) | 9 (4.1) | 8 (6.8) | 1 (2.7) | 10 (13.0) | 0.06 |

| Clinical Loss (n [%]) | 118 (17.4) | 31 (13.8) | 43 (19.6) | 19 (16.1) | 8 (21.6) | 17 (22.1) | 0.34 |

| Clinical Loss Type (n [%])b | 0.53 | ||||||

| Embryonic | 71 (53.4) | 18 (58.1) | 22 (51.2) | 10 (52.6) | 6 (75.0) | 9 (52.9) | |

| Pre-Embryonic | 36 (27.1) | 11 (35.5) | 9 (20.9) | 7 (36.8) | 1 (12.5) | 3 (17.7) | |

| Fetal Loss | 9 (6.8) | 1 (3.2) | 5 (11.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (12.5) | 1 (5.9) | |

| Stillbirth | 4 (3.0) | 1 (3.2) | 2 (4.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.9) | |

| Otherc | 13 (9.8) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (11.6) | 2 (10.5) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (17.7) | |

| Gestational Age of Loss | 9.9 ± 4.1 | 10.1 ± 5.5 | 10.1 ± 4.1 | 8.2 ± 1.7 | 11.9 ± 2.9 | 9.9 ± 3.7 | 0.26 |

| Pre-eclampsia d | 58 (9.0) | 19 (8.8) | 20 (9.4) | 8 (7.2) | 6 (16.7) | 5 (7.3) | 0.51 |

| Gestational Diabetesd | 20 (3.1) | 6 (2.8) | 9 (4.2) | 2 (1.8) | 1 (2.8) | 2 (2.9) | 0.81 |

Analyses performed via chi-square or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate for categorical variables and analysis of variance for continuous variables.

Among the live births (n=518)

Among those with a clinical loss (n=118)

Other included ectopic (n=8), very early (n=3), or unknown (n=2)

n=645

Table 4.

Incidence of secondary obstetric outcomes according to interpregnancy interval (n=677 women)

| Relative Risk (95% Confidence Interval) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Interpregnancy interval | Outcome/Total n (%) | Model 1 | P-valuea | Model 2 | P-valueb | |

| Peri-implantation Loss | 0–3mo | 13/225 (5.8) | 1.4 (0.6–3.1) | 0.44 | 1.6 (0.7–3.6) | 0.30 |

| 3–6mo | 9/220 (4.1) | REF | na | REF | na | |

| 6–9mo | 8/118 (6.8) | 1.7 (0.7–4.2) | 0.26 | 1.9 (0.7–4.9) | 0.18 | |

| 9–12mo | 1/37 (2.7) | 0.6 (0.1–4.7) | 0.67 | 0.7 (0.1–4.4) | 0.68 | |

| >12mo | 10/77 (13.0) | 3.5 (1.5–8.3) | 0.01 | 3.7 (1.5–9.2) | 0.01 | |

|

| ||||||

| Peri-implantation Loss | ≤ 3 months vs. >3 months | 13/225 (5.7) vs. 28/452 (6.2) | 0.9 (0.5–1.7) | 0.71 | 1.0 (0.5–1.8) | 0.88 |

|

| ||||||

| Clinical Loss | 0–3mo | 31/225 (13.8) | 0.7 (0.5–1.1) | 0.13 | 0.7 (0.5–1.1) | 0.13 |

| 3–6mo | 43/220 (19.6) | REF | na | REF | na | |

| 6–9mo | 19/118 (16.1) | 0.8 (0.5–1.3) | 0.41 | 0.8 (0.5–1.3) | 0.35 | |

| 9–12mo | 8/37 (21.6) | 1.1 (0.6–2.1) | 0.75 | 1.1 (0.6–2.1) | 0.77 | |

| >12mo | 17/77 (22.1) | 1.1 (0.6–1.8) | 0.80 | 1.0 (0.6–1.7) | 0.91 | |

|

| ||||||

| Clinical Loss | ≤ 3 months vs. >3 months | 31/225 (13.8) vs. 87/452 (19.3) | 0.7 (0.5–1.1) | 0.12 | 0.8 (0.5–1.1) | 0.14 |

|

| ||||||

| Pregnancy Complicationc | 0–3mo | 77/225 (34.2) | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 0.22 | 1.0 (0.9–1.2) | 0.37 |

| 3–6mo | 88/220 (40.0) | REF | na | REF | na | |

| 6–9mo | 44/118 (37.3) | 0.9 (0.7–1.2) | 0.61 | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 0.89 | |

| 9–12mo | 17/37 (46.0) | 1.1 (0.8–1.6) | 0.55 | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | 0.94 | |

| >12mo | 36/77 (46.8) | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) | 0.40 | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 0.15 | |

|

| ||||||

| Pregnancy Complicationc | ≤ 3 months vs. >3 months | 77/225 (34.2) vs. 185/452 (40.9) | 0.8 (0.7–1.0) | 0.12 | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 0.24 |

Analyses performed via multivariate relative risk (RR) estimation by Poisson regression with robust error variance.

Model 1: Adjusted for age, race, BMI, eligibility criteria, and gestational age of prior loss.

Model 2: Adjusted for age, race, BMI, eligibility criteria, gestational age of prior loss, and months tried to conceive for most recent pregnancy.

Pregnancy complication includes peri-implantation loss, clinical loss, preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, or preterm birth.

For this study of EAGeR women whose last outcome was a pregnancy loss, 9.0% had preeclampsia, 3.1% had gestational diabetes, and 8.1% had preterm birth among those achieving a live birth. The unadjusted and adjusted risks for preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, and preterm birth did not differ for IPI ≤ 3 months as compared to IPI > 3 months nor across 3-month IPI groups (data not shown). Similarly, the risk for any pregnancy complication was similar across 3-month IPI groups.

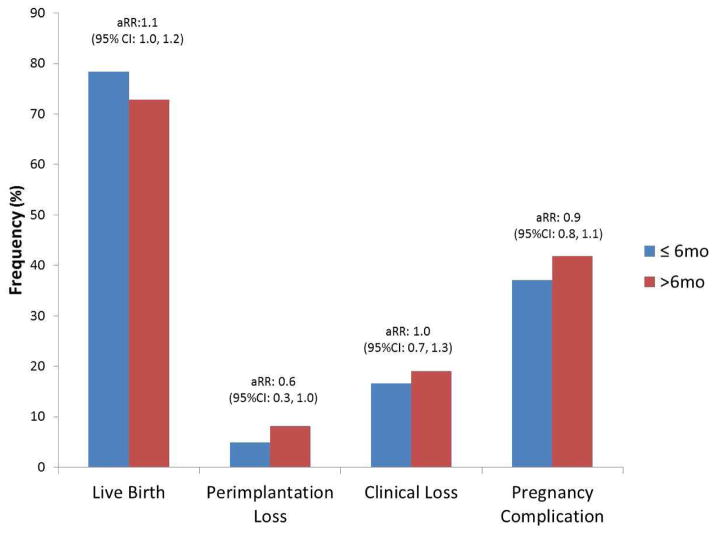

Inclusion of either treatment group (e.g., aspirin or placebo) or the intercourse frequency in the prior 12 months did not appreciably alter the effect measures (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2) nor did adjustment for additional demographic, lifestyle or reproductive history characteristics. For women with an IPI ≤ 6 months versus > 6 months, we found similar relative risks for live birth, pregnancy loss, and any pregnancy complication (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Pregnancy outcomes for women with an interpregnancy interval ≤ 6 months versus > 6 months.

1 Adjusted for age, race, BMI, eligibility criteria, gestational age of prior loss, and months tried to conceive for most recent pregnancy.

Comment

Women conceiving within 3 months of their last pregnancy loss had similar live birth rates and rates of obstetric complications as those who conceived ≥ 3 months from their last pregnancy loss. This study is unique in that it includes women with very short IPIs of less than 3 months with the added strength that participants were enrolled preconceptionally and followed closely while trying to conceive.

Current guidelines from the WHO recommend a minimum IPI of at least 6 months after a spontaneous or elective abortion.8 This recommendation is based on one retrospective study of 258,108 Latin American women who had a previous abortion (spontaneous and induced).9 They reported greater rates of adverse obstetric outcomes (including low birth weight <2500g, preterm delivery <37, and premature rupture of membranes) for those with a post-abortion IPI of 0–2 and 3–5 months as compared to women with a post-abortion IPI of 18–23 months. While this is the largest study of its kind, findings from this study should be interpreted with caution given that no distinction was made between spontaneous and induced abortion. This was done in part because of the stigma and illegality associated with induced abortion.9 Furthermore, because of the illegality of induced abortion in Latin America, it may be assumed that safe abortions were not available to these women at the time of the study.

Subsequent contemporary studies on women with one or more spontaneous abortions suggest reproductive outcomes are best for an IPI less than 6 months, with an inverse relationship between live birth rate and increasing IPI.10–13 Love et al reported decreasing live birth rates of 85.2%, 77.8%, and 73.3% with increasing IPI of <6 months, 12–18 months, and > 24 months respectively among Scottish women who had a spontaneous abortion in their first pregnancy.10 These results are consistent with a recent prospective study of 4,619 Egyptian women with a history of spontaneous abortion in their first pregnancy.13 El Behery and colleagues noted that women who conceived within 6 months were twice as likely to have a live birth as compared to those who conceived over 12 months after their first spontaneous abortion.13

Although these studies provide evidence that reproductive outcomes, particularly live birth rates, are better for an IPI less than 6 months after a spontaneous abortion, they do not focus on whether an interval of at least 3 months is necessary to optimize outcomes. Only one study in an industrialized country has reported pregnancy outcomes for IPI ≤ 3 months.11 This was a limited secondary analysis of retrospectively collected data for 325 Israeli women, finding no significant differences in pregnancy loss rates for IPI ≤ 3 months as compared to IPI 3–6 months and > 6 months.11

Women with a longer IPI in our study tended to have lower (though non-significant) rates of live births and increased peri-implantation losses, a pattern also reported in other studies.10,12 Unlike these studies, the women with a longer IPI within our study were not significantly older, nor were they more likely to be smokers, or alcohol consumers. However, we found that these women were more likely to be nulliparous. It is possible that women with a longer IPI are more likely to have an unidentified underlying condition causing delayed conception and adverse pregnancy outcomes such as infertility or sub-fertility.

Because much of the literature makes comparisons between an IPI of ≤ 6 months versus a longer IPI, we also estimated the relative risks for live birth, pregnancy loss, and any pregnancy complication for women with an IPI ≤ 6 months versus > 6 months and found no significant difference. However, these results should be interpreted with some qualifications, since our cohort consisted of women actively trying to achieve pregnancy (only 34.3% of our cohort had an IPI > 6 months) while other studies primarily investigated IPIs of longer duration and used different IPI for their reference groups.

There are few studies examining adverse perinatal outcomes and IPI after a prior pregnancy loss. El Behery et al identified a lower rate of preeclampsia and preterm birth < 36 weeks for women with IPI less than 6 months as compared to women with IPI greater than 12 months.13 Love and colleagues noted a higher risk for PTB < 36 weeks among those with IPI greater than 24 months as compared to shorter IPI.10 While our study did not identify an association between varying IPI intervals and preterm birth or preeclampsia, we were limited in the numbers of obstetric complications to make definitive conclusions regarding these outcomes.

Our study had several limitations. First, as a secondary analysis, the trial was not primarily designed and powered to examine live birth incidence and adverse pregnancy outcomes associated with IPI. Second, not all women were enrolled in the study immediately after their pregnancy loss. Accordingly we lack some data regarding whether women were trying to conceive and on sub-clinical pregnancy loss in the months between their last loss and enrollment in the EAGeR trial. This bias, however, was likely reduced by the fact that the median delay between the most recent pregnancy loss and study entry was 11.9 weeks. Furthermore, including the duration couples tried to conceive for the most recent pregnancy as a marker of potential undiagnosed subfertility within our multivariate models did not alter our findings. Results also remained robust even after additional consideration of intercourse frequency within the year prior to study enrollment and the time interval from last pregnancy loss to time the couple began to attempt conception. Nevertheless, a future study that is designed and powered to assess differences in pregnancy outcomes by IPI, enrolling and prospectively following women right after their loss through pregnancy outcome, is recommended.

There were also numerous strengths of the study. Most importantly, all participants were actively trying to conceive and were closely monitored for evidence of early pregnancy loss using home and clinic pregnancy tests and early first trimester sonogram. Such studies are difficult to conduct and as a consequence have been rare. Second, the timing and details of prior losses were carefully and objectively documented. Third, the study was prospective, allowing for early and accurate gestational dating, as well as characterization of the type of pregnancy loss. Finally, there were a large number of participants with a range of IPIs including over 200 women who became pregnant less than 3 months after a pregnancy loss.

Traditional recommendations are to delay conception for 3 months following early pregnancy loss.7 These recommendations stem from theoretical concerns regarding normalization of hormone levels rather than clear scientific evidence. Pregnancy loss is an emotionally distressing event and attempting to conceive again is often the only thing that makes couples who have experienced a loss feel better.19 In addition, some women have medical reasons to avoid delays in becoming pregnant such as advanced maternal age, optimal windows with regard to chronic medical problems, or infertility. Our study suggests that IPI ≤ 3 months is not associated with a lower rate of live birth, and appears to be comparable to those with an IPI > 3 months. Similarly, longer IPI after a prior loss does not appear to be associated with decreased rates of pregnancy loss, preterm birth, or preeclampsia. Thus, reevaluation of the traditional recommendation for women with a prior pregnancy loss to wait at least 3 months before attempting conception after a prior loss is warranted.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Financial Support: This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland (Contract Nos. HHSN267200603423, HHSN267200603424, HHSN267200603426).

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors report no conflict of interest.

Presentation: This paper was presented in part as a poster at the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine 34th Annual Meeting, Hilton New Orleans Riverside, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA, February 3–8, 2014 (final abstract ID# 412)

Reprints will not be available.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Rai R, Regan L. Recurrent miscarriage. Lancet. 2006;368:601–611. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR, O’Connor JF, et al. Incidence of early loss of pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:189. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198807283190401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu BP, Rolfs RT, Nangle BE, Horan JM. Effect of the interval between pregnancies on perinatal outcomes. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:589. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902253400801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fuentes-Afflick E, Hessol NA. Interpregnancy interval and the risk of premature infants. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:383–90. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00583-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhu BP, Haines KM, Le T, McGrath-Miller K, Boulton ML. Effect of the interval between pregnancies on perinatal outcomes among white and black women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:1403–10. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.118307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conde-Agudelo A, Rosas-Bermudez A, Kafury-Goeta AC. Birth spacing and risk of adverse perinatal outcomes – a metaanalysis. JAMA. 2006;295:1809–23. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.15.1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katz VL. Spontaneous and recurrent abortion: etiology, diagnosis, treatment. In: Katz VL, editor. Comprehensive Gynecology. 5. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Inc; 2007. p. 381. [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. [Accessed May 22, 2014];Report of a WHO technical consultation on birth spacing. 2005 http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/birth_spacing.pdf.

- 9.Conde-Agudelo A, Belizan JM, Breman R, Brockman SC, Rosas-Bermudez A. Effect of the interpregnancy interval after an abortion on maternal and perinatal health in Latin America. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005;89(Suppl 1):S34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Love ER, Bhattacharya S, Smith NC, Bhattacharya S. Effect of interpregnancy interval on outcomes of pregnancy after miscarriage: retrospective analysis of hospital episode statistics in Scotland. BMJ. 2010;341:c3967. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bentolila Y, Ratzon R, Shoham-Vardi I, Serjienko R, Mazor M, Bashiri A. Effect of interpregnancy interval on outcomes of pregnancy after recurrent pregnancy loss. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013;26:1459–64. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2013.784264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DaVanzo J, Hale L, Rahman M. How long after a miscarriage should women wait before becoming pregnant again? Multivariate analysis of cohort data from Matlab, Bangladesh. BMJ Open. 2012;2 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001591. pii: e001591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.El Behery MM, Siam S, Seksaka MA, Ibrahim ZM. Reproductive performance in the next pregnancy for nulliparous women with history of first trimester spontaneous abortion. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2013;288:939–44. doi: 10.1007/s00404-013-2809-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schisterman EF, Silver RM, Perkins NJ, et al. A randomised trial to evaluate the effects of low-dose aspirin in gestation and reproduction: design and baseline characteristics. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2013;27:598–609. doi: 10.1111/ppe.12088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silver RM, Branch DW, Goldenberg R, Iams JD, Klebanoff MA. Nomenclature for pregnancy outcomes: time for a change. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:1402–8. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182392977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Hypertension in pregnancy: Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:1122–31. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000437382.03963.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zou G. A Modified Poisson Regression Approach to Prospective Studies with Binary Data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:702–6. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spiegelman D. und Hertzmark, Easy SAS Calculations for Risk or Prevalence Ratios and Differences. E Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162:199–205. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cuisinier M, Janssen H, De Graauw C, Bakker S, Hoogduin C. Pregnancy following miscarriage: course of grief and some determining factors. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 1996;17:168–74. doi: 10.3109/01674829609025678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.