Abstract

Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (CCHF) is an expanding tick-borne hemorrhagic disease with increasing human and animal health impact. Immense knowledge was gained over the past 10 years mainly due to advances in molecular biology, but also driven by an increased global interest in CCHFV as an emerging/re-emerging zoonotic pathogen. In the present article we discuss the advances in research with focus on CCHF ecology, epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnostics, prophylaxis and treatment. Despite tremendous achievements, future activities have to concentrate on the development of vaccines and antivirals/therapeutics to combat CCHF. Vector studies need to continue for better public and animal health preparedness and response. We conclude with a roadmap for future research priorities.

Keywords: Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever, ecology, epidemiology

1. Introduction

Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (CCHF) is characterized by fever and hemorrhagic manifestations with fatality up to 30%1. It is endemic in focal areas in Asia, Europe and Africa, with geographic distribution following that of Hyalomma ticks, the main vectors of CCHF virus (CCHFV). Apart from the bite of an infected tick (Figure 1), the virus can be transmitted to humans by direct contact with blood or tissues of viremic patients or animals. Nosocomial and intra-family transmission have been reported2, 3.

Figure 1.

Tick on the back of a patient.

The disease typically presents an incubation phase (1–9 days), prehemorrhagic and hemorrhagic phases (in severe cases), and convalescence5. The hemorrhagic manifestations range from petechiae and epistaxis to extended ecchymosis and bleeding from various systems (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

A patient with Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever presenting ecchymosis on the right lower extremity and the pelvic area.

CCHFV (genus Nairovirus, family Bunyaviridae) is an enveloped single-stranded negative sense RNA virus with a tri-segmented genome consisting of a small, medium and large RNA segments, encoding for the nucleocapsid protein (N), the glycoproteins Gn and Gc and the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, respectively. CCHFV is characterized by a great genetic variability with complex evolutionary patterns6. Due to its high pathogenicity and the lack of approved vaccines and specific intervention strategies, CCHFV must be handled under biosafety level 4 (BSL-4) containment. The recent emergence of CCHFV causing either sporadic human infections7, 8 or epidemics in previously unaffected areas9, 10, has raised animal and public health concerns. As a result, great progress has been made in CCHF pathogenesis, diagnostics and epidemiology/ecology, while efforts are underway to design effective vaccines and treatment strategies including antiviral and immunotherapeutic compounds. This article summarizes and discusses the progress in the field over the past decade and identifies knowledge gaps and future research perspectives.

2. Advances in eco-epidemiology

CCHFV is maintained in nature by ixodid ticks mainly of the genus Hyalomma11, 12. Additional tick species from the genera Dermacentor, Boophilus, Amblyomma, Rhipicephalus, and Haemaphysalis, have been implicated in harboring CCHFV in the field or were shown to be experimentally infected, but there is little evidence for a role of these species in natural transmission or maintenance of CCHFV13. Thus, it appears that Hyalomma ticks are necessary for the maintenance of active CCHFV foci even during periods of enzootic or silent activity. Studies on the vectorial abilities of soft ticks (family Argasidae) confirmed that these ticks cannot transmit the virus despite getting infected while feeding on viremic hosts and detectable virus in blood remnants14. Thus, reports on the vectorial capacity of other ticks are unreliable and less convincing15–17. Detection of CCHFV RNA in those tick species is likely the result of virus uptake while feeding on viremic hosts.

In addition to the fundamental role played by the presence and abundance of the most prominent tick vectors, an adequate density of reservoir hosts seems to be necessary in order to reach a critical transmission rate of CCHFV12, 18. For other tick-borne diseases, such as tick-borne encephalitis or Lyme disease, it has been speculated that changes in host abundance, social habitats, economic fluctuations, environmental conditions, and to a lesser extent climate, have increased the disease incidence rate19–22. Climate change, however, has been frequently linked to CCHF outbreaks. The development of a process-driven model for H. marginatum, the main vector in the Mediterranean region23, has provided an adequate framework to study the impact of climate features on virus spread by the tick vector in an endemic area24 and to evaluate the effect of host abundance on viral transmission25. It has been proposed that such study should precede the active surveillance of the tick vectors26. Results from modeling approaches indicated that the Balkans are the area in the Mediterranean basin where climate trends might have a larger impact on the spread of H. marginatum24. The modeling study provided evidence that the most important factor for increased transmission of CCHFV might be the increased abundance of large hosts (e.g. wild and domestic ungulates), on which adult ticks feed, thus, allowing further amplification through transovarial transmission24. Further field surveys investigating the infestation and infection rates of different wild animals (mammals and birds) would enable a better understanding of the virus transmission cycle.

In the past years, the importance of habitat fragmentation and its consequences in the maintenance of active CCHFV foci have been discussed. There is evidence that a fragmented landscape with multiple smaller patches of vegetation within a matrix of unsuitable tick habitat, may lead to isolated populations of both ticks and hosts producing an amplification cycle with ticks feeding on infected hosts27. Due to the isolation of these host populations, the local movements of hosts are limited, and, therefore, new naive animals carrying uninfected ticks do not dilute the prevalence rate in the isolated patch27. For CCHFV eco-epidemiology, the degree of habitat patchiness contributes to the increased contact rate among reservoir hosts, humans, and ticks.

3. Advances in basic virology

Humans are the only known host that develops disease after CCHFV infection. The major pathological abnormalities of CCHF are related to vascular dysfunction resulting in hemorrhagic manifestations largely driven by erythrocyte and plasma leakage into the tissues28. Endothelial damage can contribute to coagulopathy by deregulated stimulation of platelet aggregation, which in turn activates the intrinsic coagulation cascade, ultimately leading to clotting factor deficiency and hemorrhages. Vascular leakage may be caused either by destruction of endothelial cells or by a disruption of the endothelial cell junctions. It is still unknown whether vascular dysfunction is due to a direct effect of virus on the endothelial cells or a consequence of a cytokine storm. In fact, for other hemorrhagic fever viruses, such as Ebola and Dengue viruses, there is a correlation among the level of the pro-inflammatory response, vascular leakage, and disease severity29–33. Key players in disease progression are interleukin (IL)-10, IL-1, IL-6 and tumour necrosis factor-a (TNF-a)32. In vitro studies showed that CCHFV replicates in human dendritic cells and macrophages resulting in the release of TNF-a, IL-6 and IL-8, which then can activate endothelial cells in vitro34, 35. In contrast to milder CCHF cases, elevated levels of pro-inflammatory mediators (such as TNF-, IL-6, IL-10) and serum markers of vascular activation (sICAM-1 and sVCAM-1) have been detected in fatal CCHF cases36–38. These clinical observations are mirrored in an in vitro experiment, in which it was demonstrated that CCHFV infected endothelial cells can up-regulate ICAM-1 and VCAM-I39. It was shown that CCHFV induces apoptosis in vitro late post infection in human target cell lines40, 41. This suggests that CCHFV may induce plasma leakage from the vessels and cause loss of lymphocytes by apoptosis. However, it remains unclear whether induction of apoptosis is due to direct effects of virus replication to indirect effects induced by certain pro-inflammatory mediators known to induce apoptosis.

An efficient and rapid host response against virus invasion is the production of type I interferons (IFN-a/b). Besides their role as antiviral messengers, IFNs posses a wide range of biological activities including inhibition of cell proliferation, regulation of apoptosis, and immune-modulation42, 43. CCHFV is IFN-sensitive44 and despite the strong inhibitory effect of type I IFNs on its replication in vitro, CCHFV still runs its devastating course in the human host, probably because virus-induced IFN production in the host is inefficient or not timely. It has been shown that IFN has no significant activity against an already established CCHFV infection45. This indicates that CCHFV strongly counteracts IFN signalling. It has been demonstrated that CCHFV employs a range of strategies to evade and counteract the innate immune response. RIG-I recognition is circumvented by removal of the 5' triphosphate group from the viral genome46, IRF-3 activation, mediated by a particle recognition pathway is delayed by a yet to be identified viral factor45, and NF-kappaB activation and the antiviral action of ISG15 are down regulated by the OTU domain on the L protein47. The knowledge that IFN plays a key role in controlling CCHFV replication was utilized for the development of CCHF animal models in adult mice lacking IFN responses48–50. Recently, these models have been used to understand the pro-inflammatory response during active CCHFV infections50. Most probably, capillary fragility caused by CCHFV is due to multiple host-induced mechanisms in response to CCHFV infection.

4. Advances in clinical virology

A prompt and accurate laboratory diagnosis during the first days of the disease is critical for both patient's management and prevention of transmission. Virus isolation is seldom tried for CCHF diagnosis, due to the time-consuming procedure and the biocontainment needed for handling specimens. Molecular methods are increasingly used for the detection of CCHFV in acute clinical samples. Furthermore, in combination with genetic characterization an immediate insight into the molecular epidemiology of the disease causing CCHFV strain is achieved. The tremendous genetic variability of CCHFV as well as the potential for reassortment and recombination events has to be considered for the design of diagnostic assays and vaccines.

4.1. Molecular methods

Several real-time PCR-based diagnostic assays for rapid detection of CCHFV in clinical samples have been described; primers are designed either to detect the majority of CCHFV genetic lineages or they are lineage-specific51–58. A commercial quantitative real time RT-PCR kit is currently available. Assays using simple equipment have been developed, including a low-density macroarray59, a high-density resequencing DNA microarray60, a method based on padlock probes with colorimetric readout61, and a loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay62. Some of these assays seem more practical than the real-time PCR for rapid detection of CCHFV in the field and in rural hospitals with resource-poor settings, but assay efficiency under those conditions remains to be evaluated on site. The padlock probes have been used for in situ rolling circle amplification detection of viral and complementary RNA molecules, enabling studies of CCHFV replication63.

4.2. Serologic methods

Serological methods have greatest use after the 5th day of illness. Antibody production is delayed or even absent in CCHF patients with severe disease. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and indirect immunofluorescent assay (IFA) kits are commercially available for the detection of human IgM and IgG CCHFV-specific antibodies. The CCHFV N protein induces an early, strong and long-lasting immune response in humans and therefore the native or recombinant N protein is often used as the antigen in serological assays. Capture ELISAs for detection of CCHFV-specific IgM (μ-capture) and IgG (rheumatoid factor capture) have been developed64, while the recent development of an indirect ELISA for the parallel measurement of CCHFV IgG and IgM antibodies using recombinant N protein as antigen removes the reliance on polyclonal antibody preparations65.

The characteristics, performance, and on-site applicability of serologic and molecular assays for diagnosis of CCHF have been evaluated66. An international external quality assessment of CCHFV molecular diagnostics showed differences in performance depending on the method used, the type of CCHFV strain targeted, the virus load of the sample and the laboratory performing the test, indicating that there is a need for improved performance and standardized protocols67. As with most viral diseases, for accurate laboratory diagnosis a combination of molecular and serologic methods should be applied taking always into consideration the day of sampling during illness, the course of the disease and the immunological status of the patient.

Neutralization assays are of great confirmatory value; however, CCHFV has to be handled in BSL-4 containment making application of this diagnostic assay difficult. A recently described pseudo-plaque reduction neutralization test was suggested as an alternative, fast, reproducible and sensitive method for the measurement of CCHFV neutralizing antibodies68.

5. Advances in prophylaxis and therapy

A number of studies regarding treatment and prevention have been recently performed. No specific therapy has been confirmed as effective enough for the treatment of CCHF patients. Differential diagnosis is very important. The initial nonspecific symptoms of CCHF can mimic other infections, leading to misdiagnosis and delay of proper treatment. CCHF patients must be closely monitored for effective supportive treatment69, 70.

5.1. Supportive treatment

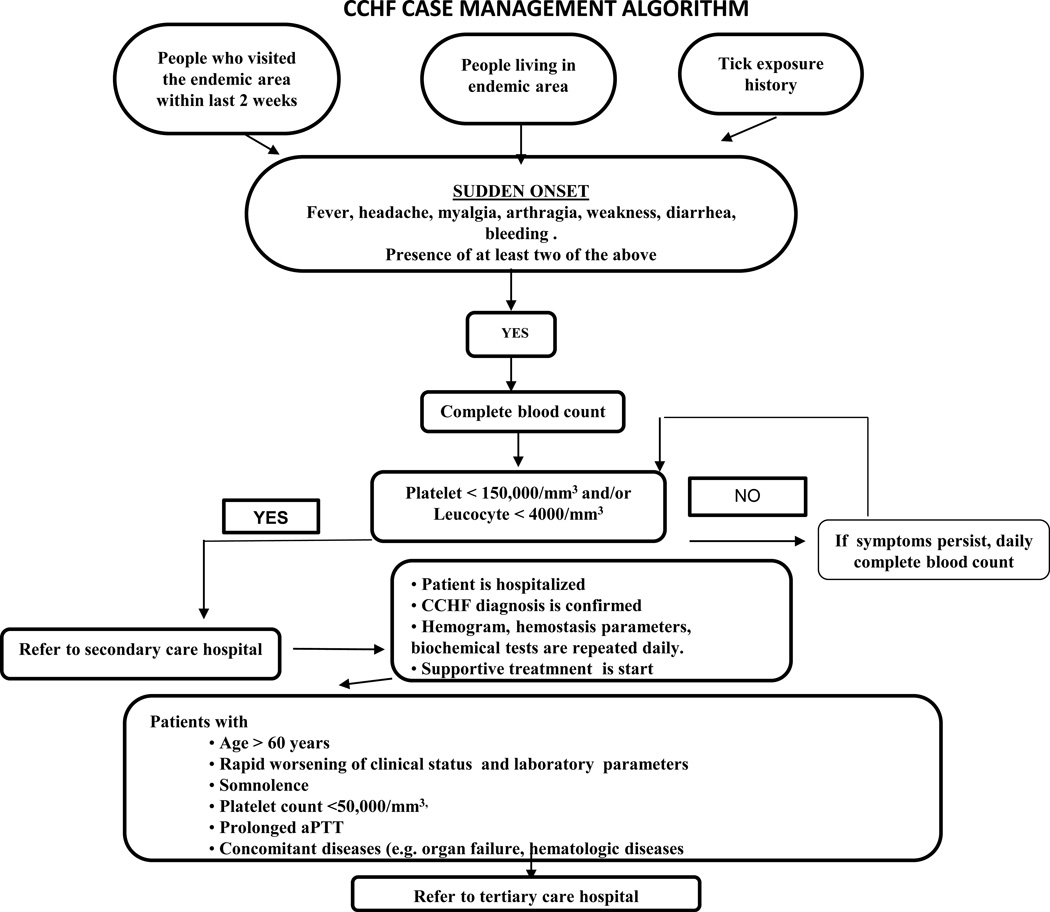

The most important step in the management of CCHF patients is supportive treatment70, 71. Figure 3 summarizes an algorithm of CCHF case management.

Figure 3.

Algorithm of CCHF case management.

Patients with a confirmed CCHF diagnosis are usually hospitalized for monitoring. Laboratory tests, like complete while blood cells count, serum electrolytes and transaminases, renal function tests, and coagulation parameters (such as prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time and international normalized ratio) are very informative and critical. Patients with organ failure must be monitored in intensive care units, especially for respiratory and renal complications69, 72.

Fluid substitution, blood transfusion, and other supportive therapies, such as fresh frozen plasma and platelet transfusions, should be initiated as soon as possible if indicated. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) should be given to severe CCHF patients with refractory thrombocytopenia69, 72. There is also a study reporting the efficacy of methylprednisolone in CCHF cases73.

5.2. Antiviral therapy

Ribavirin is the only antiviral drug that has been used for the treatment of CCHF cases. It is a broad spectrum synthetic purine nucleoside analogue that acts by several mechanisms which are not totally understood yet. Ribavirin inhibits CCHFV replication in vivo and in vitro in a concentration-dependent manner74. Its effectiveness in humans is largely based on clinical observations69. Overall, however, the effectiveness of ribavirin is controversial. Some studies have suggested that ribavirin is effective when given in the early stage of the disease75. However, other recent studies do not support the efficacy of ribavirin. One such study reported that despite a decline in the use of ribavirin from 68% to 12% in Turkey during 2004–2007, there was no change in CCHF mortality rate, which remained stable at around 5%76. A randomized prospective study performed in the Black Sea region of Turkey did not determine a positive effect on clinical and laboratory parameters in CCHF patients given ribavirin and hospitalization was even prolonged in ribavirin-treated patients; mortality rates were similar in patients receiving ribavirin or not77. A systematic review and meta-analysis did not support the idea that ribavirin is effective in the CCHF treatment, since the results of patients treatment with ribavirin were compared with those of patients without ribavirin treatment and found that ribavirin did not increase the survival rate, did not shorten the length of hospitalization and did not reduce the need for blood and blood products78. Similar results have been reported from another meta-analysis reporting drug-related adverse effects in patients receiving ribavirin79. On the other hand, combination therapy might be beneficial as shown in a study involving six patients who were treated with corticosteroids and ribavirin early in infection80.

Flusin et al. reported that the combination of ribavirin and small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) exhibited a synergistic antiviral effect against Hazara virus in an animal model suggesting that the treatment might be also beneficial for CCHFV81. Others investigated compounds/drugs such as recombinant and natural interferon-alpha, however no human studies have been conducted82.

5.3. Specific immunoglobulin therapy

In the past, some CCHF patients have been treated with horse immunoglobulin and human convalescent serum. However, data regarding the effectiveness of this approach is still limited69, 79. Specific immunoglobulin derived from plasma of convalescent CCHF patients has been given intramuscularly for prophylactic and therapeutic purposes, particularly in Bulgaria83. In a study performed in Turkey, CCHFV hyperimmunoglobulin prepared from healthy donors was given to 15 patients, who had high CCHF viral load (108 copies/mL). The application of anti-CCHF hyperimmunoglobulin may represent a new therapeutic approach, particularly for high-risk patients84.

5.4. Post exposure prophylaxis

The benefit of post exposure prophylaxis following contact with CCHFV is debatable. However, studies on health care workers with a high risk of transmission and percutaneous exposure suggest that ribavirin prophylaxis might be beneficial85–87. It is recommended that ribavirin be started immediately after injury/exposure based on the knowledge that the benefit of ribavirin is best when administered early in infection70. According to these studies, ribavirin prophylaxis can be recommended for health personnel with high risk exposure to CCHFV such as through percutaneous injury88, 89. Ribavirin prophylaxis is administered orally as a 2g loading dose, followed by 4 g/day for 4 days and 2 g/day for 6 days90. Future studies need to address the efficacy, dose and duration of ribavirin prophylaxis for CCHF exposure.

5.5. Modes of prevention

As with all tick-borne diseases, persons have to pay attention to avoid tick bites. Since CCHFV is highly infectious after direct contact with secretions or blood of viremic patients or animals, in particular livestock, individuals occupied in animal husbandry and slaughterhouses, as well as healthcare workers, must follow infection control procedures, such as use of gloves, masks, gowns and face shields, which proved to be sufficient for protection87, 91. Barrier nursing and patient isolation are needed while managing CCHF patients.

5.6. Vaccines

Initial attempts to develop CCHF vaccines began in the 1960s69. The first inactivated vaccine was based on brain tissue derived from CCHFV infected suckling mice and rats. This vaccine was approved in 1970 by the Soviet Ministry of Health. In the same year, serum samples were collected from approximately 2,000 healthy individuals before vaccination and after 2nd and 3rd vaccination, and tested for the presence of neutralizing CCHFV antibodies. Neutralizing CCHFV antibodies developed within 1–4 weeks after the 3rd dose, but titers decreased 3–6 months thereafter69, 82. In 1974, the Soviet vaccine was licensed in Bulgaria and was administered to military, medical personnel and agricultural workers in places where CCHF is endemic. The Bulgarian Ministry of Health reported that over a 22-year period the number of CCHF cases decreased four-fold after the introduction of vaccination85. Modern vaccine approaches need to be urgently developed, like virus-like particle-based or DNA vaccines. Discovery and evaluation of new CCHFV vaccine candidates are difficult in the absence of proper animal model and a lack of interest by industry. The recently developed knouckout mouse models may be temporary solutions to drive urgently needed research efforts for vaccine development69, 91.

6. Ten-year research roadmap

CCHFV is the most widely distributed tick-borne hemorrhagic fever virus with endemic areas in more than 30 countries. Recent emergence and re-emergence of CCHFV underline the importance of this pathogen for global human and animal health. The tick vector of CCHFV is widely distributed in the Old World; its movement and expansion will define known and new endemic regions for this pathogen and CCHF disease. Despite improving knowledge on the biology of the virus, a better understanding of the clinical aspects of the disease and the establishment of rapid and sensitive diagnostics over the past 10 years, there are still many gaps to be filled. Future research needs to particularly focus on the vector-virus interaction, the impact of infection on livestock and other animals, and the development of vaccines and treatment strategies for humans and animals.

A priority future goal should be studies on CCHFV dynamics in reservoirs and vectors. The role of birds, climate change and reservoir/host abundance for the distribution of ticks and the establishment of new CCHFV endemic areas should be investigated. The creation of an epidemiological predictive risk map for CCHF would be of tremendous impact for ‘One Health’ preparedness.

The development of countermeasures such as vaccines and treatment options are urgent priorities. Vaccine strategies should be based on new recombinant technologies as they are generally safer, better suited for production purposes, and, probably easier approved by authorities. Gain in knowledge and better understanding of the virus biology have already produced targets for intervention, but new targets need to be identified and current strategies need to be moved forward towards efficacy testing and approval. The lack of proper animal models is a huge drawback and the development of immunocompetent CCHF disease models is an urgent short-term need. The lack of success in this area of research most likely has multiple reasons, but CCHFV adaptation through tissue culture passaging could be a simple explanation. Therefore, there is a need to establish tick colonies for virus seed stock propagation; those colonies would also be a tremendous tool to study the interaction of the virus with its tick vector.

Overall, the path forward for the next 5–10 years is laid out by the needs for public and animal health preparedness and response. Given the importance and urgency of CCHF for the health systems of many nations, short- and long-term deliverables are being expected over the next decade.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Anna Papa and Ali Mirazimi are part of the CCH Fever Network (Collaborative Project) supported by the European Commission under the Health Cooperation Work Program of the 7th Framework Program (Grant agreement no. 260427). Ali Mirazimi is also supported by the Swedish Research Council. Heinz Feldmann is supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIAID, NIH.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Ethical approval: Not required.

References

- 1.Papa A. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever and hantavirus infections. In: Maltezou H, Gikas A, editors. Tropical and Emerging Infectious Diseases. Kerala, India: Research Signpost; 2010. pp. 49–73. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aradaib IE, Erickson BR, Mustafa ME, et al. Nosocomial outbreak of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever, Sudan. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:837–839. doi: 10.3201/eid1605.091815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Naderi HR, Sarvghad MR, Bojdy A, Hadizadeh MR, Sadeghi R, Sheybani F. Nosocomial outbreak of Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever. Epidemiol Infect. 2011;139:862–866. doi: 10.1017/S0950268810002001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sargianou M, Papa A. Epidemiological and behavioural factors associated with CCHFV infections in humans. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2013 doi: 10.1586/14787210.2013.827890. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ergonul O. Clinical and pathological features of Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever. In: Ergonul O, Whitehouse CA, editors. Crimean Congo Hemorrhagic Fever A Global Perspective Dordrecht. The Netherlands: Springer; 2007. pp. 207–220. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anagnostou V, Papa A. Evolution of Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever virus. Infect Genet Evol. 2009;9:948–954. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2009.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Papa A, Dalla V, Papadimitriou E, Kartalis GN, Antoniadis A. Emergence of Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever in Greece. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16:843–847. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crimean-Congo hem. fever - Uganda (03): (KM, AG) fatal. 2013 (Accessed at. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karti SS, Odabasi Z, Korten V, et al. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever in Turkey. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:1379–1384. doi: 10.3201/eid1008.030928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mishra AC, Mehta M, Mourya DT, Gandhi S. Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever in India. Lancet. 2011;378:372. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60680-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoogstraal H. The epidemiology of tick-borne Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever in Asia, Europe, and Africa. J Med Entomol. 1979;15:307–417. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/15.4.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Estrada-Pena A, Jameson L, Medlock J, Vatansever Z, Tishkova F. Unraveling the ecological complexities of tick-associated crimean-congo hemorrhagic Fever virus transmission: a gap analysis for the Western palearctic. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2012;12:743–752. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2011.0767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watts DM, Ksiazek TG, Linthicum KJ. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever. In: Monath TP, editor. The arboviruses: Epidemiology and Ecology. Boca Raton, FL: CRS Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shepherd AJ, Swanepoel R, Cornel AJ, Mathee O. Experimental studies on the replication and transmission of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus in some African tick species. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1989;40:326–331. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1989.40.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Albayrak H, Ozan E, Kurt M. Molecular Detection of Crimean-Congo Haemorrhagic Fever Virus (CCHFV) but not West Nile Virus (WNV) in Hard Ticks from Provinces in Northern Turkey. Zoonoses Public Health. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1863-2378.2009.01316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tekin S, Bursali A, Mutluay N, Keskin A, Dundar E. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus in various ixodid tick species from a highly endemic area. Vet Parasitol. 2011;186:546–552. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Telmadarraiy Z, Ghiasi SM, Moradi M, et al. A survey of Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever in livestock and ticks in Ardabil Province, Iran during 2004–2005. Scand J Infect Dis. 2010 doi: 10.3109/00365540903362501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hartemink NA, Randolph SE, Davis SA, Heesterbeek JA. The basic reproduction number for complex disease systems: defining R(0) for tick-borne infections. Am Nat. 2008;171:743–754. doi: 10.1086/587530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Randolph SE. The shifting landscape of tick-borne zoonoses: tick-borne encephalitis and Lyme borreliosis in Europe. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2001;356:1045–1056. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2001.0893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sumilo D, Asokliene L, Bormane A, Vasilenko V, Golovljova I, Randolph SE. Climate change cannot explain the upsurge of tick-borne encephalitis in the Baltics. PLoS One. 2007;2:e500. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sumilo D, Bormane A, Vasilenko V, et al. Upsurge of tick-borne encephalitis in the Baltic States at the time of political transition, independent of changes in public health practices. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;15:75–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.02121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jaenson T, Lindgren E. The range of Ixodes ricinus and the risk of contracting Lyme borreliosis will increase northwards when the vegetation period becomes longer. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2011;2:44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Estrada-Pena A, Martinez M, Munoz MJ. A population model to describe the distribution and seasonal dynamics of the tick Hyalomma marginatum in the Mediterranean Basin. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2011;58:213–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1865-1682.2010.01198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Estrada-Pena A, N S, Estrada-Sánchez A. An assessment of the distribution and spread of the tick Hyalomma marginatum in the western Palearctic under different climate scenarios. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2012;12:758–768. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2011.0771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Estrada-Pena A, Ruiz-Fons F, Acevedo P, Gortazar C, de la Fuente J. Factors driving the circulation and possible expansion of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus in the western Palearctic. J Appl Microbiol. 2013 doi: 10.1111/jam.12039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gale P, Estrada-Pena A, Martinez M, et al. The feasibility of developing a risk assessment for the impact of climate change on the emergence of Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever in livestock in Europe: a Review. J Appl Microbiol. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2009.04638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Estrada-Pena A, Vatansever Z, Gargili A, Ergonul O. The trend towards habitat fragmentation is the key factor driving the spread of Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138:1194–1203. doi: 10.1017/S0950268809991026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ergonul O. Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:203–214. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70435-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bray M, Geisbert TW. Ebola virus: the role of macrophages and dendritic cells in the pathogenesis of Ebola hemorrhagic fever. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2005;37:1560–1566. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bray M, Pilch R. Filoviruses: recent advances and future challenges. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2006;4:917–921. doi: 10.1586/14787210.4.6.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen ST, Lin YL, Huang MT, et al. CLEC5A is critical for dengue-virus-induced lethal disease. Nature. 2008;453:672–676. doi: 10.1038/nature07013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen HC, Hofman FM, Kung JT, Lin YD, Wu-Hsieh BA. Both virus and tumor necrosis factor alpha are critical for endothelium damage in a mouse model of dengue virus-induced hemorrhage. J Virol. 2007;81:5518–5526. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02575-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lei HY, Yeh TM, Liu HS, Lin YS, Chen SH, Liu CC. Immunopathogenesis of dengue virus infection. J Biomed Sci. 2001;8:377–388. doi: 10.1007/BF02255946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Connolly-Andersen AM, Douagi I, Kraus AA, Mirazimi A. Crimean Congo hemorrhagic fever virus infects human monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Virology. 2009;390:157–162. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peyrefitte CN, Perret M, Garcia S, et al. Differential activation profiles of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus- and Dugbe virus-infected antigen-presenting cells. J Gen Virol. 2010;91:189–198. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.015701-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Papa A, Bino S, Velo E, Harxhi A, Kota M, Antoniadis A. Cytokine levels in Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever. J Clin Virol. 2006;36:272–276. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ergonul O, Tuncbilek S, Baykam N, Celikbas A, Dokuzoguz B. Evaluation of serum levels of interleukin (IL)-6, IL-10, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in patients with Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:941–944. doi: 10.1086/500836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ozturk B, Kuscu F, Tutuncu E, Sencan I, Gurbuz Y, Tuzun H. Evaluation of the association of serum levels of hyaluronic acid, sICAM-1, sVCAM-1, and VEGF-A with mortality and prognosis in patients with Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever. J Clin Virol. 2010;47:115–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Connolly-Andersen AM, Moll G, Andersson C, et al. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus activates endothelial cells. J Virol. 2011;85:7766–7774. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02469-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karlberg H, Tan YJ, Mirazimi A. Induction of caspase activation and cleavage of the viral nucleocapsid protein in different cell types during Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus infection. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:3227–3234. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.149369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rodrigues R, Paranhos-Baccala G, Vernet G, Peyrefitte CN. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus-infected hepatocytes induce ER-stress and apoptosis crosstalk. PLoS One. 2012;7:e29712. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hertzog PJ, O'Neill LA, Hamilton JA. The interferon in TLR signaling: more than just antiviral. Trends Immunol. 2003;24:534–539. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Le Bon A, Tough DF. Links between innate and adaptive immunity via type I interferon. Curr Opin Immunol. 2002;14:432–436. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(02)00354-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Andersson I, Lundkvist A, Haller O, Mirazimi A. Type I interferon inhibits Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus in human target cells. J Med Virol. 2006;78:216–222. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Andersson I, Karlberg H, Mousavi-Jazi M, Martinez-Sobrido L, Weber F, Mirazimi A. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus delays activation of the innate immune response. J Med Virol. 2008;80:1397–1404. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Habjan M, Andersson I, Klingstrom J, et al. Processing of genome 5' termini as a strategy of negative-strand RNA viruses to avoid RIG-I-dependent interferon induction. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2032. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Frias-Staheli N, Giannakopoulos NV, Kikkert M, et al. Ovarian tumor domain-containing viral proteases evade ubiquitin- and ISG15-dependent innate immune responses. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;2:404–416. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bereczky S, Lindegren G, Karlberg H, Akerstrom S, Klingstrom J, Mirazimi A. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus infection is lethal for adult type I interferon receptor-knockout mice. J Gen Virol. 2010;91:1473–1477. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.019034-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bente DA, Alimonti JB, Shieh WJ, et al. Pathogenesis and immune response of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus in a STAT-1 knockout mouse model. J Virol. 2010;84:11089–11100. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01383-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zivcec M, Safronetz D, Scott D, Robertson S, Ebihara H, Feldmann H. Lethal Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus infection in interferon alpha/beta receptor knockout mice is associated with high viral loads, proinflammatory responses, and coagulopathy. J Infect Dis. 2013;207:1909–1921. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yapar M, Aydogan H, Pahsa A, et al. Rapid and quantitative detection of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus by one-step real-time reverse transcriptase-PCR. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2005;58:358–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Papa A, Drosten C, Bino S, et al. Viral load and Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:805–806. doi: 10.3201/eid1305.061588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ibrahim SM, Aitichou M, Hardick J, Blow J, O'Guinn ML, Schmaljohn C. Detection of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever, Hanta, and sandfly fever viruses by real-time RT-PCR. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;665:357–368. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-817-1_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Garrison AR, Alakbarova S, Kulesh DA, et al. Development of a TaqMan minor groove binding protein assay for the detection and quantification of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;77:514–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Duh D, Saksida A, Petrovec M, et al. Viral load as predictor of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever outcome. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:1769–1772. doi: 10.3201/eid1311.070222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wolfel R, Paweska JT, Petersen N, et al. Virus detection and monitoring of viral load in Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus patients. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:1097–1100. doi: 10.3201/eid1307.070068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kondiah K, Swanepoel R, Paweska JT, Burt FJ. A Simple-Probe real-time PCR assay for genotyping reassorted and non-reassorted isolates of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus in southern Africa. J Virol Methods. 2010;169:34–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Atkinson B, Latham J, Chamberlain J, et al. Sequencing and phylogenetic characterisation of a fatal Crimean - Congo haemorrhagic fever case imported into the United Kingdom, October 2012. Euro Surveill. 2012;17 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wolfel R, Paweska JT, Petersen N, et al. Low-density macroarray for rapid detection and identification of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:1025–1030. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01920-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Filippone C, Marianneau P, Murri S, et al. Molecular diagnostic and genetic characterization of highly pathogenic viruses: application during Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever virus outbreaks in Eastern Europe and the Middle East. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013 doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ke R, Zorzet A, Göransson J, et al. Colorimetric nucleic acid testing assay for RNA virus detection based on circle-to-circle amplification of padlock probes. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:4279–4285. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00713-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Osman HA, Eltom KH, Musa NO, Bilal NM, Elbashir MI, Aradaib IE. Development and evaluation of loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay for detection of Crimean Congo hemorrhagic fever virus in Sudan. J Virol Methods. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Andersson C, Henriksson S, Magnusson KE, Nilsson M, Mirazimi A. In situ rolling circle amplification detection of Crimean Congo hemorrhagic fever virus (CCHFV) complementary and viral RNA. Virology. 2012;426:87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Emmerich P, Avsic-Zupanc T, Chinikar S, et al. Early serodiagnosis of acute human Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus infections by novel capture assays. J Clin Virol. 2010;48:294–295. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dowall SD, Richards KS, Graham VA, Chamberlain J, Hewson R. Development of an indirect ELISA method for the parallel measurement of IgG and IgM antibodies against Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever (CCHF) virus using recombinant nucleoprotein as antigen. J Virol Methods. 2012;179:335–341. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2011.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vanhomwegen J, Alves MJ, Zupanc TA, et al. Diagnostic assays for crimean-congo hemorrhagic fever. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18:1958–1965. doi: 10.3201/eid1812.120710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Escadafal C, Olschlager S, Avsic-Zupanc T, et al. First international external quality assessment of molecular detection of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1706. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Canakoglu N, Berber E, Ertek M, et al. Pseudo-plaque reduction neutralization test (PPRNT) for the measurement of neutralizing antibodies to Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus. Virol J. 2013;10:6. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-10-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Keshtkar-Jahromi M, Kuhn JH, Christova I, Bradfute SB, Jahrling PB, Bavari S. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever: current and future prospects of vaccines and therapies. Antiviral research. 2011;90:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ergonul O. Treatment of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever. Antiviral Res. 2008;78:125–131. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Koksal I, Yilmaz G, Aksoy F, et al. The efficacy of ribavirin in the treatment of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever in Eastern Black Sea region in Turkey. Journal of clinical virology : the official publication of the Pan American Society for Clinical Virology. 2010;47:65–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Leblebicioglu H, Bodur H, Dokuzoguz B, et al. Case management and supportive treatment for patients with Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever. Vector borne and zoonotic diseases. 2012;12:805–811. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2011.0896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dilber E, Cakir M, Erduran E, et al. High-dose methylprednisolone in children with Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever. Trop Doct. 2010;40:27–30. doi: 10.1258/td.2009.090069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tignor GH, Hanham CA. Ribavirin efficacy in an in vivo model of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus (CCHF) infection. Antiviral Res. 1993;22:309–325. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(93)90040-P. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tasdelen Fisgin N, Ergonul O, Doganci L, Tulek N. The role of ribavirin in the therapy of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever: early use is promising. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;28:929–933. doi: 10.1007/s10096-009-0728-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yilmaz GR, Buzgan T, Irmak H, et al. The epidemiology of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever in Turkey, 2002–2007. Int J Infect Dis. 2009;13:380–386. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2008.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Koksal I, Yilmaz G, Aksoy F, et al. The efficacy of ribavirin in the treatment of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever in Eastern Black Sea region in Turkey. J Clin Virol. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ascioglu S, Leblebicioglu H, Vahaboglu H, Chan KA. Ribavirin for patients with Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:1215–1222. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Soares-Weiser K, Thomas S, Thomson G, Garner P. Ribavirin for Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:207. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jabbari A, Besharat S, Abbasi A, Moradi A, Kalavi K. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever: case series from a medical center in Golestan province, Northeast of Iran (2004) Indian J Med Sci. 2006;60:327–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Flusin O, Vigne S, Peyrefitte CN, Bouloy M, Crance JM, Iseni F. Inhibition of Hazara nairovirus replication by small interfering RNAs and their combination with ribavirin. Virol J. 2011;8:249. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-8-249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Maltezou HC, Papa A. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever: epidemiological trends and controversies in treatment. BMC medicine. 2011;9:131. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Christova I, Di Caro A, Papa A, et al. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever, southwestern Bulgaria. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:983–985. doi: 10.3201/eid1506.081567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kubar A, Haciomeroglu M, Ozkul A, et al. Prompt administration of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (CCHF) virus hyperimmunoglobulin in patients diagnosed with CCHF and viral load monitorization by reverse transcriptase-PCR. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2011;64:439–443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Christova I, Kovacheva T, Georgieva D, Ivanova S, Argirov D. Vaccine against Congo-Crimean haemorrhagic fever virus – Bulgarian input in fighting the disease. Probl Inf Parasit Dis. 2010;37:7–8. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tarantola A, Ergonul O, Tattevin P. Estimates and prevention of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever risks for health-care workers. In: Ergonul O, Whitehouse CA, editors. Crimean Congo Hemorrhagic Fever A Global Perspective. Dortrecht: Springer; 2007. pp. 281–294. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ergonul O. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus: new outbreaks, new discoveries. Current opinion in virology. 2012;2:215–220. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tütüncü EEGY, Ozturk B, Kuscu F, Sencan I. Crimean Congo haemorrhagic fever, precautions and ribavirin prophylaxis: a case report. Scand J Infect Dis. 2009;41:378–380. doi: 10.1080/00365540902882434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tarantola A, Ergonul O PT. Estimates and prevention of Crimean Congo hemorrhagic fever risks for health careworkers. In: E O, W CA, editors. Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever:AGlobal Perspective. Dordrecht, NL: Springer; 2007. pp. 281–294. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tutuncu EE, Gurbuz Y, Ozturk B, Kuscu F, Sencan I. Crimean Congo haemorrhagic fever, precautions and ribavirin prophylaxis: a case report. Scand J Infect Dis. 2009;41:378–380. doi: 10.1080/00365540902882434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mertens M, Schmidt K, Ozkul A, Groschup MH. The impact of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus on public health. Antiviral research. 2013;98:248–260. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]