Abstract

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a common endocrinopathy characterized by increased ovarian androgen biosynthesis, anovulation, and infertility. PCOS has a strong heritable component based on familial clustering and twin studies. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) identified several PCOS candidate loci including, DENND1A, LHCGR, FSHR, ZNF217, YAP1, INSR, RAB5B, and C9orf3. Here, we review the functional roles of strong PCOS candidate loci focusing on FSHR, LHCGR, INSR and DENND1A. We propose that these candidates comprise a hierarchical signaling network by which DENND1A, LHCGR, INSR, RAB5B, adapter proteins, and associated downstream signaling cascades converge to regulate theca cell androgen biosynthesis. Future elucidation of the functional gene networks predicted by the PCOS GWAS will result in new diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for women with PCOS.

Keywords: PCOS, hyperandrogenism, theca, genomics, GWAS, signaling

Hyperandrogenemia and Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS)

PCOS is a common disorder that is reported to affect 5–7% women of reproductive age. The incidence of PCOS appears to be similar across racial/ethnic groups. Although there has been debate about the diagnostic criteria for PCOS, an observed hyperandrogenemia/hyperandrogenism that cannot be explained by other causes, is a hallmark of the disorder, and it is included as an essential element in all “consensus” diagnosis schemes [1, 2]. The hyperandrogenemia is widely believed to be primarily of ovarian theca cell origin, although the adrenal zona reticularis contributes androgens, mainly dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), in approximately 25% of cases. The interconnectedness between the two androgen-secreting organs in PCOS is supported by the suppression of both adrenal and ovarian androgens by oral contraception [3] or insulin sensitizing agents [4, 5]. This review focuses on the genetic component underlying androgen excess in PCOS.

The phenotype of human theca cells from normal and PCOS ovaries

Studies on freshly isolated thecal tissue from normal and PCOS ovaries, or cultures of human theca cells derived from normal and PCOS women, have demonstrated that PCOS theca secretes greater amounts of androgen than theca tissue or cells from regularly ovulating women [6–12]. Recent successes in developing conditions to propagate human theca cells isolated from individual, size-matched follicles from ovaries of normal cycling women and women with PCOS provided evidence of increased expression of the rate limiting enzyme in androgen biosynthesis, P450 17α-hydroxylase/17,20 lyase, encoded by the CYP17A1 gene. In PCOS theca cells augmented CYP17A1 expression results in the increased metabolism of progestin precursors into androgens, among other steroids [10, 13–15]. Previous molecular characterization of PCOS theca cells and normal theca cells from multiple individuals by microarray analysis and quantitative PCR established that PCOS theca cells have molecular signatures that are distinct from those in normal theca cells [16, 17]. In PCOS, this molecular signature is associated with increased expression of certain steroidogenic enzymes involved in androgen biosynthesis including CYP17A1, P450 cholesterol side chain cleavage (CYP11A), 3β-hydroxysteroid type II (HSD2B), 20α-hyroxysteroid (AKR1C1), but not steroidogenic acute regulatory factor (STARD1) [8, 9]. In addition, an array of structural proteins, cell cycle proteins, and transcription factors [16, 17], including the transcription factor GATA-6 show increased expression. GATA-6 was subsequently shown to be a transcriptional activator of the main P450 steroidogenic enzymes involved in androgen biosynthesis including CYP17A1 and CYP11A1 [18].

The genetics of PCOS

PCOS is a heterogeneous disorder with strong evidence for a genetic component [19, 20]. Although there is some evidence for autosomal dominant inheritance, most investigators believe that an oligogenic/polygenic model is most likely, a belief reinforced by the results of recent genome-wide association studies (GWAS) that have identified multiple loci associated with PCOS [20]. Incomplete penetrance, epigenetic modifications, and environmental contributions have complicated attempts to clarify the underlying mode of inheritance. Despite advances in genetic technologies, very few PCOS susceptibility genes have been validated. Numerous candidate gene association studies have been conducted, but few have yielded statistically significant associations that have been consistently replicated [20]. The publication of GWAS with large populations of Han Chinese individuals identified eleven PCOS candidate loci: DENND1A, INSR, YAP1, C9orf3, RAB5B, HMGA2, TOX3, SUMO1P1/ZNF217, THADA, FSHR and LHCGR [21, 22]. The initial study encompassed a total of 4082 cases (defined by the “Rotterdam Criteria”) and 6678 controls, and identified three loci [21] and a follow-up study involving additional patients added confirmed the three loci previously reported, and identified eight new candidate loci [22]. Four studies in European populations published soon thereafter confirmed the association of several of these loci, including the FSHR/LHCGR, DENND1A loci, as well as RAB5B and THADA [23–26]. However, it is important to recognize that different diagnostic criteria (e.g. NIH Consensus vs Rotterdam) have been used in these reported studies, which may confound interpretation.

GWAS permits discovery of unexpected loci contributing to disease risk, including those that confer only modest risk. While loci in or near the genes encoding the FSH receptor (FSHR), LH receptor (LHCGR), and insulin receptor (INSR) might have been anticipated based on the known roles of FSH, LH and insulin in controlling follicular growth, differentiation and steroidogenesis [23], pathophysiological links of the other GWAS loci to reproduction, ovarian function, steroidogenesis or the metabolic phenotype of PCOS were not readily apparent. Moreover, it is not known whether each individual gene or [27] multiple genes are involved in the PCOS phenotype, what the “causal” variants in or near these genes might be, or how they might contribute to the disease phenotype. Here, we review the functional roles of strong candidate PCOS candidate loci identified in the GWAS studies noted above, and subsequently replicated in other populations, focusing on FHSR, LHCGR, INSR and DENND1A.

Coding Sequence Variants in FSHR, LHCGR and INSR associated with PCOS and their functional significance

Follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH) and insulin, all have gonadotropic functions. Although FSH acts on granulosa cells, its regulation of granulosa cell function influences the production of paracrine factors that alter theca cell activity. Both LH and insulin have direct actions on theca cells and increase their steroidogenic activity [27]. Consequently, genetic association of the cognate receptors for these gonadotropins and PCOS is not unanticipated.

In addition to the GWAS and replication studies noted above that implicated the FSHR/LHCGR and INSR loci in PCOS, a number of family-based association studies and subsequent candidate gene studies were carried out in different populations for common single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in these genes [28–33]. Several of these SNPs result in amino acid substitutions and, therefore, might affect protein expression or function [29, 34]. The associations have not always been found, perhaps due to population differences and a limited cohort size and a limited number of genetic variants examined [30, 35].

The FSH receptor (FSHR)

Previous studies have shown that FSHR is associated with the ovarian response to FSH, thereby making it a compelling PCOS candidate gene [37]. Inactivating mutations in the FSHR gene leads to hypergonadotropic hypogonadism, and in the absence of a functional FSHR follicular development is generally halted at the preantral stage. Conversely, mutations in the transmembrane helices and the extracellular domain of FSHR are associated with spontaneous ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome [36, 37]. Several FSHR variants have been studied in association with PCOS (for e.g. two variants in exon 10: rs6165 (T307A) and rs6166 (N680S)) [28, 29, 34, 35, 38, 39]. The SNP rs6166 has been reported to be in association with PCOS in Dutch and Japanese women. Other studies have reported variants in association with circulating FSH levels [33, 35] and in vivo responses to exogenous gonadotropins and clomiphene citrate [40], suggesting that some of these variants might have functional significance in a PCOS context. However, when studied in model cell systems, the variants encoded by the major and minor SNP alleles behave identically with respect to FSH binding and signal transduction [41, 42]. Therefore, there is no clear explanation for the correlation between genotype of the FSHR variants and FSH levels or response to gonadotropins and by extension how exactly these variants contribute to PCOS is not clear.

The LH/CG receptor (LHCGR)

The LHCGR gene codes for a G-protein coupled receptor for LH and human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG). In the ovary, induction of the LHCGR during granulosa cell differentiation is responsible for the pre-ovulatory follicle to respond to the mid-cycle LH surge resulting in ovulation. In women, inactivating mutations of LHCGR are associated with increased LH levels, enlarged ovaries and oligomenorrhea. Women with inactivating LHCGR mutations have no obvious reproductive phenotype as opposed to the precocious puberty observed in males [43]. LHCGR variants have been found to be associated with PCOS in some studies [33, 44–46]. A variant in exon 10 (rs12470652) resulting in an amino acid substitution (N291S) that affects glycosylation and slightly reduces the EC50 for hCG, suggesting it might be more active, has been reported to be associated with PCOS in one small study, but not in another [46]. Another nearby SNP in exon 10 (rs2293275) that causes an amino acid substitution, S312N, has been associated with PCOS in another study [47]. Its functional significance is unknown in that it does not appear to affect glycosylation. The fact that known activating mutations of the LHCGR that cause precocious puberty in males because of premature Leydig cell activation and testosterone production are not associated with hyperandrogenemia of ovarian origin in women calls into question the notion that “hyper-responsive” LHCGR isoforms are related to theca cell dysfunction [45].

The insulin receptor (INSR)

The INSR plays a significant role in insulin metabolism and can play a critical role in PCOS pathogenesis via insulin resistance [21]. The importance of insulin signaling in PCOS is evident through the HAIR-AN syndrome (hyperandrogenism, insulin resistance acanthosis nigricans), which is a sub-phenotype of PCOS characterized by severe insulin resistance [48]. Mutations in the insulin receptor gene, especially in the tyrosine kinase domain have been implicated in HAIR-AN syndrome [49]. An early attempt to identify PCOS genes using a candidate approach of genotyping variable number tandem repeats (VNTRs) identified a statistically significant association with a marker (D19S884, allele 8) selected for its proximity to the INSR gene on chromosome 19p13.2 [50]. This association has been replicated in some but not all studies [51–54]. D19S884 was subsequently found to be in an intron of the fibrillin 3 (FBN3) gene and its relationship to INSR gene expression or function has not been established [54, 55]

A silent SNP (rs1799817) in exon 17, which encodes the tyrosine kinase domain of the INSR, has been associated with PCOS in some studies, but not others [32, 56–62]. Its functional significance (e.g., translational efficiency) in theca cell biology or insulin resistance is unknown. Other SNPs in the INSR associated with PCOS include rs225673, which resides in intron 11, its impact on INSR gene expression or its relationship to a causal genetic variation are unknown [63]. The same is true for SNPs around exon 9 that have been associated with PCOS (rs8107575, rs2245648, rs2245649, rs2963, rs2245655, and rs2962) [64].

Collectively, candidate gene association studies provide some additional support for the notion that the FSHR, LHCGR, and INSR loci are associated with PCOS, consistent with the GWAS and replication studies noted above. However, there has yet to be convincing evidence produced that the variants identified in these genes are functionally significant and contribute to the PCOS theca cell phenotype. Together, these studies also suggest an intersection between the genetic basis of PCOS and T2D in addition to the epidemiological evidence. Genes involved in gonadotropin secretion and insulin signaling may act in a common pathway or network leading to the PCOS theca cell phenotype.

DENND1A - A novel starting point for dissecting the molecular mechanisms underlying PCOS

DENND1A, also termed connecdenn 1, is a member of the conndecdenn family of proteins, which are encoded by 18 genes in humans. The domains of DENND1A are tripartite, consisting of an upstream, core, and downstream DENN domains. DENND1A functions as a guanine nucleotide exchange factor that interacts with members of the Rab family of small GTPases [65]. DENND1A is thought to be involved in clathrin-mediated endocytosis, facilitating internalization of proteins and lipids, receptor recycling, and membrane trafficking [65]. DENND1A has also been associated with phosphoinositol-3-phosphate, and endocytosis/endosome proteins [20, 65].

The DENND1A gene yields two principal transcripts via alternative splicing. DENND1A variant 1 (DENND1A.V1) which encodes a 1009 amino acid (AA) protein with a large C-terminal proline-rich domain; and DENND1A.V2, encodes a 559 AA protein that lacks the proline-rich domain, and includes a distinct C-terminal 33 AA sequence that differs from DENND1A.V1. Both DENND1A.V1 and V2 contain clathrin-binding domains, which may interact differentially with membrane adaptor proteins as a consequence of differences in their distinct C-terminal domains. Notably, as described below, DENND1A is highly expressed in ovarian theca cells and the adrenal zona reticularis, both androgen-producing tissues. Up until recently, little was known about DENND1A expression in cells and tissues related to reproduction [20].

DENND1A.V2 in PCOS theca cells

DENND1A.V2 expression is increased in PCOS theca cells

Studies using theca cells isolated from normal cycling and PCOS women provided the first evidence to demonstrate a functional relationship between augmented DENND1A.V2 and CYP17A1 expression and increased androgen biosynthesis in PCOS theca cells [66]. Immunohistochemical localization studies showed that DENND1A.V2 was increased in PCOS theca cells as compared to normal theca cells, and was localized in the cytosol and nuclei of both PCOS granulosa and theca [66]. In contrast, DENND1A.V1 protein levels are decreased in PCOS theca cells, and the ratio of DENND1A.V2 to DENND1A.V1 is increased in PCOS theca cells. DENND1A.2 mRNA is similarly increased in PCOS theca cells, and precedes the augmented induction of CYP17 mRNA and androgen biosynthesis. In subsequent studies, forced expression of DENND1A.V2 in normal cells converted the cells to a PCOS phenotype of increased CYP17A1 and CYP11A1 gene transcription and androgen biosynthesis. In contrast, knockdown DENND1A.V2 expression, or ablation of DENND1A.V2 function in PCOS theca cells utilizing DENND1A.V2 specific antibodies converts the cells to a normal phenotype.

These data provide strong evidence that increased DENND1A.V2 expression mediates augmented CYP17A1 gene expression and androgen biosynthesis in PCOS theca cells [66]. While the studies summarized above suggest that DENND1A.V2, when over expressed, can produce a theca cell PCOS phenotype, these findings do not exclude the possibility that DENND1A.V2 acts in concert with genetic variants of FSHR, LHCGR and INSR to modulate signal transduction pathways that promote thecal androgen synthesis. However, these data suggest that DENND1A.V2 is a novel therapeutic and diagnostic target for PCOS.

DENND1A.V2: a potential biomarker for PCOS?

Exosomes are small nucleic acid rich vesicles shed into blood and urine, which provide a source of RNA that can be conveniently utilized for diagnostic implications. Studies comparing DENNDD1.V2 mRNA in urine exosomes isolated from normal cycling and PCOS women demonstrated that DENND1A.V2 RNA is increased in PCOS compared to normally cycling women. These experiments provided the first evidence to suggest that increased urine exosomal DENND1A.V2 could be diagnostic for PCOS [66]. A diagnostic method based on urine exosomal RNA would have value in settings when non-invasive diagnostics are needed such as in prepubertal and adolescent females. However, this test requires extensive validation to assess its sensitivity, specificity and positive and negative predictive values.

Functional consequences of DENND1A.V2 overexpression in PCOS

To date, a genetic explanation for increased expression of DENND1A.V2 has not been identified. The DENND1A SNPs identified by GWAS are located in introns and it is not known whether they have functional roles. Moreover, whole exome sequencing has not identified DENND1A coding region variants in PCOS [25]. Possible mechanisms for overexpression include copy number variation (CNV), increased promoter activity, the influence of microRNAs on protein expression, or splicing variation favoring the production of DENND1A.V2. To date, CNVs and proximal promoter variation that could explain the increased expression of DENND1A.V2 have not been reported. At this juncture, genetic variations affecting splicing mechanisms that differentiate DENND1A.V2 from DENND1A.V1 appears to be the most likely explanation.

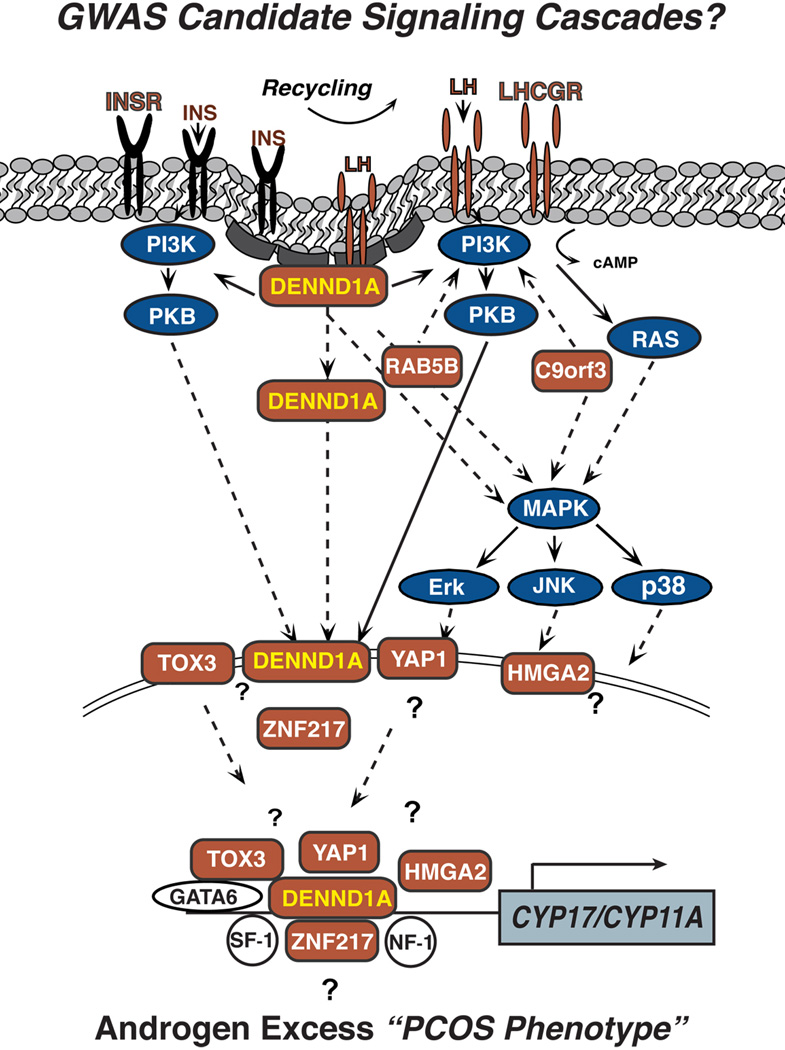

The mechanism(s) by which DENND1A.V2 alters theca cell function is not known. However, the structural features of the DENND1A.V2 protein and its cellular localization offer some important clues. First, DENND1A.V2 could modify signaling via gonadotropin or insulin receptors; perhaps biasing activation of signal transduction cascades, leading to increased expression of steroidogenic enzymes (Fig. 1). DENND1A.V2 could have direct effects in this regard, or it could modify or interfere with the action of DENND1A.V1. Since cyclic AMP-stimulated CYP17A1 and CYP11A1 gene expression and steroidogenesis is amplified by increased DENND1A.V2 expression, DENND1A.V2 appears to have a boosting effect that augments cAMP signaling. Alternatively, DENND1A.V2 localized in the nucleus could influence gene transcription, either through the transport of ligand and/or receptor into the nucleus with the activation of intra-nuclear signal transduction, or DENND1A.V2 might play a role as a scaffold for transcription factors that regulate steroidogenic enzyme gene expression (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Hypothetical model of a GWAS Signaling Cascades involved in PCOS.

The schematic shows a putative network of genes postulated to contribute to the hyperandrogenimia associated with PCOS, based on the loci identified in published GWAS and replication studies (GWAS candidates are labeled in rust). The GWAS loci associated with PCOS include: 1) plasma membrane receptors (LHCGR, FSHR INSR); 2) proteins associated with protein trafficking, endocytotic processes, and receptor recycling (DENND1A, RAB5B); and 3) transcription factors (ZNF217, YAP1, TOX3, HMG). The LH/hCG receptor, FSH-receptor, and insulin receptor are all plasma membrane receptors, which are internalized/recycled by clathrin coated pits [20]. DENND1A encodes the plasma membrane protein connecdenn 1, which is involved in clathrin-binding, endocytic processes and receptor recycling [65, 74, 86]. Ras related protein 5B (RAB5B) is a Rab-GTPase, and is also involved in membrane trafficking, endocytosis and receptor recycling [87, 88]. Yes-associated protein (YAP1), transcriptional coactivator of the p300/CBP-mediated transcription complex (TOX3), high mobility group AT-hook 2 (HMGA2), and zinc finger protein 217 (ZNF217) have all be shown to be involved in transcriptional activation/repression [75–77, 89].

Abbreviations: PCOS, polycystic ovary syndrome; GWAS, Genome Wide Association Study; DENND1A, connecdenn 1; DENND1A.V2, DENND1A variant 2; LHCGR, LH/CG receptor; YAP1, Yes-associated protein; TOX3, transcriptional coactivator of the p300/CBP-mediated transcription complex; HMGA2, high mobility group AT-hook 2; ZNF217, zinc finger protein 217; RAB5B, ras related protein 5B; INSR, insulin receptor; CYP17A1, cytochrome P450 17α-hydroxylase CYP11A1, cytochrome P450 cholesterol side chain cleavage.

Could DENND1A be a “unifying gene” in explaining multiple PCOS phenotypes?

As noted above, PCOS is associated with excess adrenal androgen levels in approximately 25% of women, consistent with an adrenal steroidogenic abnormality [19, 67–70]. The localization of DENND1A.V2 in the human adrenal zona reticularis provides evidence that alterations in expression of this isoform may contribute to the adrenal steroidogenic abnormality in addition to the thecal derangement in androgen production. DENND1A SNPs have been reported to be associated with diverse phenotypes found in PCOS women, including elevated insulin levels and endometrioid carcinoma [71, 72]. Additionally, quantitative trait analyses have linked the DENND1A locus with glucose and insulin levels and body weight in humans [73]. Thus, DENND1A.V2 could possibly contribute directly to or modify a number of PCOS phenotypes, which heretofore have not been tied to a single genetic locus.

A PCOS genetic network incorporating DENND1A

Among the loci associated with PCOS in Han Chinese, several reside in or near genes that potentially define a network. While loci in or near the genes encoding the FSH receptor, LH receptor, and insulin receptor are plausible PCOS candidates; the pathophysiological links of the other GWAS loci to reproduction, ovarian function, steroidogenesis or the metabolic phenotype of PCOS have not been readily apparent [20, 22, 74]. It is currently unknown whether each individual gene or multiple genes are involved in the PCOS phenotype, or what the functional variants in or near these genes might be, or how they might contribute to the disease phenotype.

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) network pathway analysis [75–77] from RNA-Seq expression profiles of the GWAS candidates in normal and PCOS theca cells revealed that DENND1A, ZNF217, YAP1, and HMGA2 are associated in an inter-related pathway. A review of the literature has also revealed that the GWAS candidates, LHCGR, INSR, DENND1A, RAB5B, mediate overlapping intracellular signaling pathways, including the PI3K, PKB, and/or MAPK signaling cascades [14, 78–82]. Comparison of the activation states of the AKT/PKB and MAPK/MEK/ERK signaling pathways in normal and PCOS theca cells has provided evidence that alteration of these signaling cascades may underlie increased androgen production and CYP17A1 gene expression in PCOS [14, 78]. Thus, it is conceivable that various GWAS candidates comprise a hierarchical signaling network by which DENND1A, LHCGR, INSR, RAB5B, adapter proteins, and their associated downstream signaling cascades converge to regulate CYP17A1 expression and androgen biosynthesis. Thus, DENND1A and other PCOS GWAS genes might function in a signaling pathway beginning with cell surface receptors, leading to receptor coupling/recycling, and then to downstream molecules that ultimately regulate gene transcription, either of steroidogenic genes directly, or possibly through the up-regulation of other transcription factors that directly influence steroidogenic gene promoter function (e.g., GATA6) (Fig. 1) [16, 18].

Potential Clinical Utility of DENND1A

The current diagnostic criteria for PCOS are expert based, and accordingly there are a profusion of society based and country based criteria, also proposals to split PCOS into a reproductive and a metabolic disorder [83]. The recent NIH sponsored Evidence Based Methodology Workshop on PCOS endorsed the expert based Rotterdam criteria, but stressed the need for scientifically justified criteria [84]. Having a molecular marker that may identify a pediatric female population who are just developing the disorder at adrenarche or pubarche would allow earlier intervention. Diagnosing PCOS in this population is particularly problematic lacking even expert consensus [85].

Concluding Remarks

An additional area of further exploration is the role of DENND1A variants in predicting response to common treatments for women with PCOS. Hyperandrogenism is clearly associated with the development of hirsutism in women with PCOS, and further is an important predictor of anovulation and failure to respond to ovulation induction. Thus this may be a particularly useful molecular marker for pharmacogenomics studies. Recent large multi-center studies of ovulation induction methods in women with PCOS and anovulatory infertility will certainly aid these studies.

Highlights.

GWAS identified FHSR, LHCGR, INSR and DENND1A as PCOS candidate genes.

Overexpression of DENND1A Variant 2 increases androgen biosynthesis in theca cells from normal cycling women, converting them to a PCOS phenotype.

DENND1A, LHCGR, INSR, RAB5B form a hierarchal signaling network that can influence androgen synthesis.

DENND1A.V2 is a new diagnostic and therapeutic target for PCOS.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH grants U54HD034449, R01HD058300, and R01HD033852, U10 HD038992.

Glossary

- DENN/MADD domain containing 1A (DENND1A)

is a member of the connecdenn family of proteins that function as a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) regulating clathrin-mediated endocytosis through RAB35 activation. DENND1A promotes the exchange of GDP to GTP, converting inactive GDP-bound RAB35 into its active GTP-bound form.

- Follicle-stimulating hormone receptor (FSHR)

is a transmembrane, G-protein coupled receptor found in the ovary, testis and uterus. It is required for the functioning of the Follicle Stimulating Hormone (FSH)

- Hyperandrogenemia

is a medical condition characterized by excessive levels of androgens (supraphysiologic levels of free testosterone) in the body, and one of the primary symptoms of PCOS.

- Insulin receptor (INSR)

belongs to the tyrosine kinase receptor family and is mainly involved in regulation of glucose homeostasis and plays a critical role in PCOS pathogenesis via insulin resistance.

- Luteinizing hormone/choriogonadotropin receptor (LHCGR)

is a G-protein coupled receptor predominantly expressed in the ovary and the testis and is involved in the signaling via luteinizing hormone (LH) and the human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG). In the ovary, LHCGR is involved in the follicular maturation and ovulation.

- Ovarian theca cells

are endocrine cells associated with ovarian follicles that play a key role in fertility. They produce the androgen substrate required for ovarian estrogen biosynthesis. Excessive proliferation of theca cells and ovarian hyperandrogenism is a hallmark of the most common endocrine cause of infertility.

- Zona reticularis

is the inner most layer of the adult human adrenal cortex and the source of the adrenal androgens, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and DHEA sulfate (DHEAS).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Azziz R, et al. Positions statement: criteria for defining polycystic ovary syndrome as a predominantly hyperandrogenic syndrome: an Androgen Excess Society guideline. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2006;91:4237–4245. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS consensus workshop group. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) Human Reproduction. 2004;19:41–47. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Leo V, et al. Effect of oral contraceptives on markers of hyperandrogenism and SHBG in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Contraception. 2010;82:276–280. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Azziz R, et al. Troglitazone decreases adrenal androgen levels in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertility and Sterility. 2003;79:932–937. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)04914-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Azziz R, et al. Troglitazone improves ovulation and hirsutism in the polycystic ovary syndrome: a multicenter, double blind, placebo-controlled trial. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2001;86:1626–1632. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.4.7375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilling-Smith C, et al. Evidence for a primary abnormality in theca cell steroidogenesis in the polycystic ovarian syndrome. Clin Endocrinol. 1997;47:1158–1165. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.1997.2321049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilling-Smith C, et al. Hypersecretion of androstenedione by isolated thecal cells from polycystic ovaries. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1994;79:1158–1165. doi: 10.1210/jcem.79.4.7962289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nelson VL, et al. Augmented androgen production is a stable steroidogenic phenotype of propagated theca cells from polycystic ovaries. Molecular Endocrinology. 1999;13:946–957. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.6.0311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nelson VL, et al. The biochemical basis for increased testosterone production in theca cells propagated from patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2001;86:5925–5933. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.12.8088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wickenheisser JK, et al. Differential activity of the cytochrome P450 17alpha-hydroxylase and steroidogenic acute regulatory protein gene promoters in normal and polycystic ovary syndrome theca cells. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2000;85:2304–2311. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.6.6631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Magoffin DA. Ovarian enzyme activities in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertility and Sterility. 2006;86(Suppl 1):S9–S11. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jakimiuk AJ, et al. Luteinizing hormone receptor, steroidogenesis acute regulatory protein, and steroidogenic enzyme messenger ribonucleic acids are overexpressed in thecal and granulosa cells from polycystic ovaries. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2001;86:1318–1323. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.3.7318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wickenheisser JK, et al. Dysregulation of cytochrome P450 17alpha-hydroxylase messenger ribonucleic acid stability in theca cells isolated from women with polycystic ovary syndrome. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2005;90:1720–1727. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nelson-Degrave VL, et al. Alterations in mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase and extracellular regulated kinase signaling in theca cells contribute to excessive androgen production in polycystic ovary syndrome. Molecular Endocrinology. 2005;19:379–390. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wickenheisser JK, et al. Increased cytochrome P450 17alpha-hydroxylase promoter function in theca cells isolated from patients with polycystic ovary syndrome involves nuclear factor-1. Molecular Endocrinology. 2004;18:588–605. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wood JR, et al. The molecular signature of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) theca cells defined by gene expression profiling. J Reprod Immunol. 2004;63:51–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2004.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wood JR, et al. The molecular phenotype of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) theca cells and new candidate PCOS genes defined by microarray analysis. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278:26380–26390. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300688200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ho CK, et al. Increased transcription and increased messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) stability contribute to increased GATA6 mRNA abundance in polycystic ovary syndrome theca cells. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2005;90:6596–6602. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Legro R, et al. Evidence for a genetic basis for hyperandrogenemia in polycystic ovary syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci (USA) 1998;95:14956–14960. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strauss JF, 3rd, et al. Persistence pays off for PCOS gene prospectors. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2012;97:2286–2288. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen ZJ, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies susceptibility loci for polycystic ovary syndrome on chromosome 2p16.3–2p21 and 9q33.3. Nat Genet. 2011;43:55–59. doi: 10.1038/ng.732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shi Y, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies eight new risk loci for polycystic ovary syndrome. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1020–1025. doi: 10.1038/ng.2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goodarzi MO, et al. Replication of association of DENND1A and THADA variants with polycystic ovary syndrome in European cohorts. J Med Genet. 2012;49:90–95. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2011-100427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Welt CK, et al. Variants in DENND1A are associated with polycystic ovary syndrome in women of European ancestry. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2012;97:E1342–E1347. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-3478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eriksen MB, et al. Genetic alterations within the DENND1A gene in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) PloS one. 2013;8:e77186. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Louwers YV, et al. Cross-ethnic meta-analysis of genetic variants for polycystic ovary syndrome. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2013;98:E2006–E2012. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-2495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Franks S, et al. Insulin action in the normal and polycystic ovary. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1999;28:361–378. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8529(05)70074-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Unsal T, et al. Genetic polymorphisms of FSHR, CYP17, CYP1A1, CAPN10, INSR, SERPINE1 genes in adolescent girls with polycystic ovary syndrome. Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics. 2009;26:205–216. doi: 10.1007/s10815-009-9308-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dolfin E, et al. FSH-receptor Ala307Thr polymorphism is associated to polycystic ovary syndrome and to a higher responsiveness to exogenous FSH in Italian women. Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics. 2011;28:925–930. doi: 10.1007/s10815-011-9619-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fu L, et al. Association study between FSHR Ala307Thr and Ser680Asn variants and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) in Northern Chinese Han women. Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics. 2013;30:717–721. doi: 10.1007/s10815-013-9979-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ioannidis A, et al. Polymorphisms of the insulin receptor and the insulin receptor substrates genes in polycystic ovary syndrome: a Mendelian randomization meta-analysis. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism. 2010;99:174–183. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2009.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Talbot JA, et al. Molecular scanning of the insulin receptor gene in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1996;81:1979–1983. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.5.8626868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mutharasan P, et al. Evidence for chromosome 2p16.3 polycystic ovary syndrome susceptibility locus in affected women of European ancestry. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2013;98:E185–E190. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-2471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gu BH, et al. Genetic variations of follicle stimulating hormone receptor are associated with polycystic ovary syndrome. International Journal of Molecular Medicine. 2010;26:107–112. doi: 10.3892/ijmm_00000441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu XQ, et al. Association between FSHR polymorphisms and polycystic ovary syndrome among Chinese women in north China. Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics. 2014;31:371–377. doi: 10.1007/s10815-013-0166-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huhtaniemi I. The Parkes lecture. Mutations of gonadotrophin and gonadotrophin receptor genes: what do they teach us about reproductive physiology? Journal of Reproduction and Fertility. 2000;119:173–186. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.1190173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aittomaki K, et al. Mutation in the follicle-stimulating hormone receptor gene causes hereditary hypergonadotropic ovarian failure. Cell. 1995;82:959–968. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90275-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Du J, et al. Two FSHR variants, haplotypes and meta-analysis in Chinese women with premature ovarian failure and polycystic ovary syndrome. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism. 2010;100:292–295. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2010.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Conway GS, et al. Mutation screening and isoform prevalence of the follicle stimulating hormone receptor gene in women with premature ovarian failure, resistant ovary syndrome and polycystic ovary syndrome. Clinical Endocrinology. 1999;51:97–99. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.1999.00745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Overbeek A, et al. Clomiphene citrate resistance in relation to follicle-stimulating hormone receptor Ser680Ser-polymorphism in polycystic ovary syndrome. Human Reproduction. 2009;24:2007–2013. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sudo S, et al. Genetic and functional analyses of polymorphisms in the human FSH receptor gene. Molecular Human Reproduction. 2002;8:893–899. doi: 10.1093/molehr/8.10.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Simoni M, et al. Isoforms and single nucleotide polymorphisms of the FSH receptor gene: implications for human reproduction. Human Reproduction Update. 2002;8:413–421. doi: 10.1093/humupd/8.5.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Toledo SP, et al. An inactivating mutation of the luteinizing hormone receptor causes amenorrhea in a 46,XX female. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1996;81:3850–3854. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.11.8923827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu N, et al. Association of the genetic variants of luteinizing hormone, luteinizing hormone receptor and polycystic ovary syndrome. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology : RB&E. 2012;10:36. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-10-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Latronico AC, et al. The effect of distinct activating mutations of the luteinizing hormone receptor gene on the pituitary-gonadal axis in both sexes. Clinical Endocrinology. 2000;53:609–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2000.01135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Piersma D, et al. LH receptor gene mutations and polymorphisms: an overview. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2007:260–262. 282–286. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2005.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Capalbo A, et al. The 312N variant of the luteinizing hormone/choriogonadotropin receptor gene (LHCGR) confers up to 2.7-fold increased risk of polycystic ovary syndrome in a Sardinian population. Clinical endocrinology. 2012;77:113–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2012.04372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rager KM, Omar HA. Androgen excess disorders in women: the severe insulin-resistant hyperandrogenic syndrome, HAIR-AN. The Scientific World Journal. 2006;6:116–121. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2006.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Globerman H, Karnieli E. Analysis of the insulin receptor gene tyrosine kinase domain in obese patients with hyperandrogenism, insulin resistance and acanthosis nigricans (type C insulin resistance) International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders. 1998;22:349–353. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Urbanek M, Legro RS, Driscoll DA, et al. Thirty-seven candidate genes for polycystic ovary syndrome: strongest evidence for linkage is with follistatin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999;96:8573–8578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Villuendas G, et al. Association between the D19S884 marker at the insulin receptor gene locus and polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertility and Sterility. 2003;79:219–220. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)04570-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tucci S, et al. Evidence for association of polycystic ovary syndrome in caucasian women with a marker at the insulin receptor gene locus. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2001;86:446–449. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.1.7274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stewart DR, et al. Fine Mapping of Genetic Susceptibility to Polycystic Ovary Syndrome on Chromosome 19p13.2 and Tests for Regulatory Activity. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2006;91(10):4112–4117. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ewens KG, et al. Family-based analysis of candidate genes for polycystic ovary syndrome. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2010;95:2306–2315. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xie GB, et al. Microsatellite polymorphism in the fibrillin 3 gene and susceptibility to PCOS: a case-control study and meta-analysis. Reproductive Biomedicine Online. 2013;26:168–174. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2012.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee EJ, et al. Single nucleotide polymorphism in exon 17 of the insulin receptor gene is not associated with polycystic ovary syndrome in a Korean population. Fertility and Sterility. 2006;86:380–384. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.12.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen ZJ, et al. Correlation between single nucleotide polymorphism of insulin receptor gene with polycystic ovary syndrome. 2004;39(9):582–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jin L, et al. A novel SNP at exon 17 of INSR is associated with decreased insulin sensitivity in Chinese women with PCOS. Molecular Human Reproduction. 2006;12:151–155. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gal022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mukherjee S, et al. Genetic variation in exon 17 of INSR is associated with insulin resistance and hyperandrogenemia among lean Indian women with polycystic ovary syndrome. European Journal of Endocrinology / European Federation of Endocrine Societies. 2009;160:855–862. doi: 10.1530/EJE-08-0932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ramezani Tehrani F, et al. Relationship between polymorphism of insulin receptor gene, and adiponectin gene with PCOS. Iranian Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 2013;11:185–194. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lee EJ, et al. A novel single nucleotide polymorphism of INSR gene for polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertility and Sterility. 2008;89:1213–1220. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xu X, et al. Family association study between INSR gene polymorphisms and PCOS in Han Chinese. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology : RB&E. 2011;9:76. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-9-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Goodarzi MO, et al. Replication of association of a novel insulin receptor gene polymorphism with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertility and Sterility. 2011;95:1736–1741. e1731–e1711. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hanzu FA, et al. Association of insulin receptor genetic variants with polycystic ovary syndrome in a population of women from Central Europe. Fertility and Sterility. 2010;94:2389–2392. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Marat AL, et al. DENN domain proteins: regulators of Rab GTPases. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011;286:13791–13800. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R110.217067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McAllister JM, et al. Overexpression of a DENND1A isoform produces a polycystic ovary syndrome theca phenotype. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111:E1519–E1527. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400574111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Azziz R, et al. The Androgen Excess and PCOS Society criteria for the polycystic ovary syndrome: the complete task force report. Fertility and Sterility. 2009;91:456–488. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Legro RS, et al. Elevated dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate levels as the reproductive phenotype in the brothers of women with polycystic ovary syndrome. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2002;87:2134–2138. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.5.8387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ehrmann DA, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome as a form of functional ovarian hyperandrogenism due to dysregulation of androgen secretion. Endocrine Reviews. 1995;16:322–353. doi: 10.1210/edrv-16-3-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yildiz BO, Azziz R. The adrenal and polycystic ovary syndrome. Reviews in endocrine & metabolic disorders. 2007;8:331–342. doi: 10.1007/s11154-007-9054-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cui L, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlations of PCOS susceptibility SNPs identified by GWAS in a large cohort of Han Chinese women. Human Reproduction. 2013;28:538–544. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang Z, et al. Variants in DENND1A and LHCGR are associated with endometrioid adenocarcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;2:403–405. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wisconsin BPHMCo. QTL report providing DENND1A phenotype and disease descriptions, mapping, a as well as links to markers and candidate genes. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 74.Allaire PD, et al. The Connecdenn DENN domain: a GEF for Rab35 mediating cargo-specific exit from early endosomes. Molecular Cell. 2010;37:370–382. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.12.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Basu S, et al. Akt phosphorylates the Yes-associated protein, YAP, to induce interaction with 14-3-3 and attenuation of p73-mediated apoptosis. Molecular Cell. 2003;11:11–23. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00776-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cowger JJ, et al. Biochemical characterization of the zinc-finger protein 217 transcriptional repressor complex: identification of a ZNF217 consensus recognition sequence. Oncogene. 2007;26:3378–3386. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yuan SH, et al. TOX3 regulates calcium-dependent transcription in neurons. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:2909–2914. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805555106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Munir I, et al. Insulin augmentation of 17alpha-hydroxylase activity is mediated by phosphatidyl inositol 3-kinase but not extracellular signal-regulated kinase-1/2 in human ovarian theca cells. Endocrinology. 2004;145:175–183. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhang HY, et al. Activation and significance of the PI3K/Akt pathway in endometrium with polycystic ovary syndrome patients. Zhonghua fu chan ke za zhi. 2012;47:19–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ciaraldi TP. Molecular defects of insulin action in the polycystic ovary syndrome: possible tissue specificity. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2000;13(Suppl 5):1291–1293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hojlund K, et al. Impaired insulin-stimulated phosphorylation of Akt and AS160 in skeletal muscle of women with polycystic ovary syndrome is reversed by pioglitazone treatment. Diabetes. 2008;57:357–366. doi: 10.2337/db07-0706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tee MK, et al. Pathways leading to phosphorylation of p450c17 and to the posttranslational regulation of androgen biosynthesis. Endocrinology. 2008;149:2667–2677. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dunaif A, Fauser BC. Renaming PCOS--a two-state solution. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2013;98:4325–4328. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-2040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Executive Summary of National Institutes of Health Evidence-Based Methodology Workshop for Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome. [Accessed September 13, 2013];2012 at http://prevention.nih.gov/workshops/2012/pcos/docs/PCOS_Final_Statement.pdf.

- 85.Legro RS, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2013;98:4565–4592. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-2350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Marat AL, et al. Connecdenn 3/DENND1C binds actin linking Rab35 activation to the actin cytoskeleton. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2012;23:163–175. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-05-0474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Stenmark H. Rab GTPases as coordinators of vesicle traffic. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:513–525. doi: 10.1038/nrm2728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Stenmark H, Olkkonen VM. The Rab GTPase family. Genome Biol. 2001;2 doi: 10.1186/gb-2001-2-5-reviews3007. Reviews 3007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Noro B, et al. Molecular dissection of the architectural transcription factor HMGA2. Biochemistry. 2003;42:4569–4577. doi: 10.1021/bi026605k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]