Abstract

Despite the clear efficacy of methadone for opioid dependence, one less desirable phenomenon associated with methadone may be weight gain. We examined changes in body mass index (BMI) among patients entering methadone treatment. A retrospective chart review was conducted for 96 patients enrolled in an outpatient methadone clinic for ≥6 months. The primary outcome of BMI was assessed at intake and a subsequent physical examination approximately 1.8±0.95 years later. Demographic, drug use and treatment characteristics were also examined. There was a significant increase in BMI following intake (p < 0.001). Mean BMIs increased from 27.2±6.8 to 30.1±7.7 kg/m2, translating to a 17.8-pound increase (10% increase in body weight) in the overall patient sample. Gender was the strongest predictor of BMI changes (p < 0.001), with significantly greater BMI increases in females than males (5.2 vs. 1.7 kg/m2, respectively). This translates to a 28-pound (17.5%) increase in females vs. a 12-pound (6.4%) increase in males. In summary, methadone treatment enrollment was associated with clinically significant weight gain, particularly among female patients. This study highlights the importance of efforts to help patients mitigate weight gain during treatment, particularly considering the significant health and economic consequences of obesity for individuals and society more generally.

INTRODUCTION

Opioid abuse and dependence are significant public health problems in the United States, costing $56 billion annually and including emergency department visits, premature death, HIV, hepatitis, criminal activity and lost workdays (Birnbaum et al., 2009). Agonist maintenance is the most effective treatment for opioid dependence and dramatically reduces morbidity, mortality and spread of infectious disease (Johnson et al., 2009; Stotts et al., 2009). Methadone, a full muopioid, is the most commonly used medication for treatment of opioid dependence and has been widely demonstrated to reduce illicit drug use, infectious disease and mortality (Ball & Ross, 1991).

Despite the clear efficacy of methadone treatment for opioid dependence, one less desirable phenomenon associated with treatment may include weight gain (Nolan et al., 2007; Rajs et al., 2004). Prior studies have suggested that opioid administration is associated with weight gain and glycemic dysregulation. A recent review by Mysels and Sullivan (2010) reported that activation of the mu-opioid receptor is associated with increased sweet taste preference, hyperglycemia induced by direct action on pancreatic islet cells, and potential insulin resistance caused by dietary preference for sugary foods. Increased preference for and ingestion of sweet foods can result in subsequent weight gain. Among patients receiving methadone treatment specifically, when questioned about potential side effects associated with their treatment, 80% of patients complain of weight gain (Gronbladh & Ohlund, 2011). In a retrospective chart review of methadone-maintained patients, Mysels and colleagues (2011) reported mean weight increases of 1.86% and 3.67% between treatment intake and the 3- and 6-month assessments, respectively. While these increases may appear small, they translated to an approximate 10-lb weight gain during the first 6 months of treatment. However, that study utilized a small sample of methadone-maintained patients (n=16) and their analyses were restricted to the first six months following intake, representing a limited timeframe for a treatment paradigm that often continues for years. Overall, the potential weight-increasing effects of methadone have clear public health implications, as overweight and obesity are associated with increased risk of heart disease, diabetes, stroke and premature death (CDC, 2012).

In the present study, we sought to examine changes in body mass index (BMI) among patients entering methadone treatment while extending upon prior studies in several ways. First, we included a larger sample of patients than used previously. Second, the timeframe of monitoring in our chart review encompassed a longer duration than was used in prior studies. Finally we included additional demographic, drug use and treatment characteristics in an effort to identify variables that may predict weight gain during treatment.

METHODS

A review of patient charts was conducted for opioid-dependent adults admitted to an outpatient methadone maintenance treatment program in New England between 2002 and 2011. To be included in the analyses, patients had to remain in treatment for ≥ 6 months and provide height and weight measurements at intake and a subsequent physical examination. Exclusion criteria included patients who were pregnant at intake or who became pregnant during treatment, as well as those who had transferred from another methadone clinic. The authors received approval from the University of Vermont Institutional Review Board prior to conducting chart reviews and data analyses.

Measures

Each participant’s Body Mass Index (BMI) was assessed at treatment intake (Time 1) and at a subsequent physical examination (Time 2), with a mean±SD interval between the two measurements of 1.8±0.9 (range: 0.67 – 6.0) years. BMI is a widely-used and reliable measurement of the relative percentage of adiposity and muscle mass in the human body, in which mass in kilograms is divided by height in meters squared (kg/m2). The calculation is used as an index of obesity (Centers for Disease Control, 2011). BMIs lower than 18.5 kg/m2 are regarded as underweight, between 18.5 and 24.9 kg/m2 are considered normal weight, those between 25–29.9 kg/m2 overweight, and BMIs >30 kg/m2 obese.

Several additional self-report and staff-administered questionnaires were administered at treatment intake which permitted characterization of patients’ current and past alcohol and drug use. These included the Addiction Severity Index (ASI; McClellan, 1985), Michigan Alcohol Screening Test (MAST; Selzer, 1971), as well as demographics (e.g., age, gender) and opioid use (e.g., history of intravenous drug use, primary opioid of abuse) characteristics at intake. Patients’ methadone dose at the time of second weight assessment was also documented.

ANALYSES

The primary outcome was BMI (kg/m2). Outcomes are also presented in pounds for several reasons: First, inclusion of pounds aids interpretation among readers less familiar with BMI. Second, presentation of the data in pounds permits comparison of our findings with prior studies which solely reported their methadone-associated weight gains in terms of pounds (e.g., Mysels et al., 2011). Finally, the use of BMI as a marker for adiposity may have limitations, especially in adult overweight (BMI 25</=30) males (Pasco et al., 2014; Romero-Corral et al., 2008). Thus, clinically significant weight gain (>/= 5% total body weight per Food and Drug Association) may provide a more sensitive estimate of weight changes during treatment.

A two-tailed paired t-test was performed to compare BMI at Time 1 vs. 2 and patients’ time in treatment between males and females. Hierarchical linear regression was used to examine predictors of BMI changes during treatment. Predictors included age, gender, time in treatment (e.g., the interval between BMI assessments), lifetime history of intravenous drug use (i.e., IV or no IV), patients’ methadone dose, and patients’ primary opioid of abuse at treatment intake (i.e., heroin, prescription opioids, both). A test for co-linearity among predictors was computed prior to determining the final statistical model. Statistical significance was determined based on alpha =0.05 (two-sided). Analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics 22 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

RESULTS

One hundred ninety-five charts were reviewed and 96 met eligibility criteria for inclusion. The remaining 99 charts were excluded, with the majority excluded due to either missing biometric data at either Time 1 or 2 or to a positive pregnancy status. Patient characteristics are presented in Table 1. There was a significant increase in mean BMI following entry into methadone treatment (p <0.001), with mean BMIs increasing from 27.2±6.8 to 30.1±7.7 kg/m2 at Times 1 and 2, respectively, for an overall change of 2.9 kg/m2 (CI 2.2–3.7, 95% confidence). In terms of pounds, mean weight increased from 177.6 to 195.4 pounds, representing an increase of 17.8 pounds (10% increase in body weight).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics (N=96)

| Demographics | |

| % Male | 64% |

| % Caucasian | 98% |

| Age, yrs | 38??9.2 |

| Drug use | |

| % Reporting ever used IV | 65% |

| Primary opioid of abuse | |

| Prescription opioids | 48% |

| Heroin | 24% |

| Combination | 28% |

| MAST score | 9.75 |

| Methadone dose, mg (range) | 116 (30–260) |

| Addiction Severity Index Composite Subscalesb | |

| Opiate | 0.44??0.25 |

| Cocaine | 0.06??0.16 |

| Drug | 0.27??0.13 |

| Alcohol | 0.04??0.10 |

| Employment | 0.60??0.32 |

| Legal | 0.14??0.19 |

| Family/Social | 0.15??0.18 |

| Psychiatric | 0.29??0.24 |

| Medical | 0.74??0.36 |

Data are presented as mean ?? SD unless otherwise specified.

Subscale score range: 0–1.

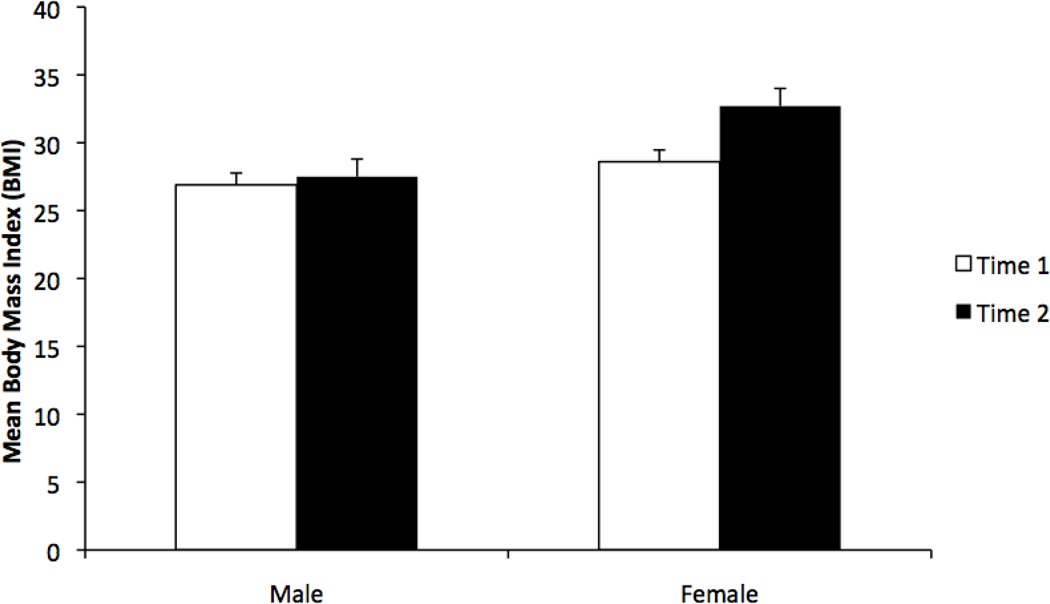

Examination of co-linearity among the predictor variables determined that they were not significantly correlated and thus they were entered into the regression model (Table 2). Gender was the only variable associated with BMI changes during treatment (ß=3.5, t87=4.78, p<.001, model R2=.23). The increase in BMI was significantly greater in females, with an increase of 5.2 kg/m2 in females (27.5 and 32.7 at Times 1 and 2 respectively) vs. 1.7 kg/m2 in males (26.9 and 28.6 at Times 1 and 2 respectively; Figure 1). When presented in pounds, mean weight for females increased from 159.9 to 187.9 pounds, representing an increase of 28.0 pounds (17.5% increase in body weight). Mean weight for males increased from 187.7 to 199.7 pounds, representing a 12-pound (6.4%) increase. When we examined whether this difference in weight gain between males and females could be explained by the length of time in treatment, there was no evidence that this was the case (p=0.85). In addition, time in treatment did not differ between genders, with males and females in treatment an average of 640.8 vs. 669.6 days, respectively (p=0.696). Finally, we descriptively examined the percentage of patients, within each gender, that fell into each of the BMI categories (i.e., underweight, normal weight, overweight, obese) at the two BMI assessment time points (Table 3).

Table 2.

Predictors of BMI Change During Methadone Treatment

| Unstandardized Coefficients |

95% Confidence Interval for B | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | B | Std. Error | t | Sig. | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |

| 1 | (Constant) | 1.656 | .447 | 3.703 | <.001 | .768 | 2.545 |

| Gender | 3.501 | .733 | 4.776 | <.001 | 2.045 | 4.957 | |

| 2 | (Constant) | 1.263 | .807 | 1.565 | .121 | −.340 | 2.866 |

| Gender | 3.488 | .736 | 4.740 | <.001 | 2.026 | 4.950 | |

| Time in treatment | .001 | .001 | .587 | .559 | −.001 | .003 | |

| 3 | (Constant) | 2.388 | 1.602 | 1.491 | .140 | −.794 | 5.570 |

| Gender | 3.440 | .740 | 4.650 | <.001 | 1.971 | 4.910 | |

| Time in treatment | .001 | .001 | .777 | .439 | −.001 | .003 | |

| Age | −.033 | .041 | −.814 | .418 | −.114 | .048 | |

| 4 | (Constant) | 2.107 | 1.637 | 1.287 | .201 | −1.146 | 5.361 |

| Gender | 3.362 | .747 | 4.503 | <.001 | 1.878 | 4.845 | |

| Time in treatment | .001 | .001 | .809 | .420 | −.001 | .003 | |

| Age | −.031 | .041 | −.774 | .441 | −.112 | .049 | |

| History of IV use | .646 | .755 | .856 | .395 | −.855 | 2.147 | |

| 5 | (Constant) | 1.353 | 1.862 | .727 | .469 | −2.346 | 5.053 |

| Gender | 3.304 | .751 | 4.402 | <.001 | 1.812 | 4.796 | |

| Time in treatment | .001 | .001 | .742 | .460 | −.001 | .003 | |

| Age | −.033 | .041 | −.800 | .426 | −.114 | .048 | |

| History of IV use | .625 | .757 | .826 | .411 | −.879 | 2.130 | |

| Methadone dose | .007 | .009 | .856 | .394 | −.010 | .025 | |

| 6 | (Constant) | 2.668 | 2.178 | 1.25 | .224 | −1.662 | 6.997 |

| Gender | 3.305 | .753 | 4.387 | <.001 | 1.807 | 4.802 | |

| Time in treatment | .001 | .001 | .861 | .392 | −.001 | .003 | |

| Age | −.036 | .042 | −.852 | .397 | −.120 | .048 | |

| History of IV use | .146 | .954 | .153 | .879 | −1.751 | 2.042 | |

| Methadone dose | .008 | .009 | .934 | .353 | −.009 | .026 | |

| Primary opioid | −.819 | 1.013 | −.809 | .421 | −2.833 | 1.194 | |

| Change Statistics | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | R | R Square | R Square Change |

F Change | df1 | df2 | Sig. F Change |

| 1 | .446 | .199 | .199 | 22.807 | 1 | 92 | .000 |

| 2 | .449 | .202 | .003 | .345 | 1 | 91 | .559 |

| 3 | .456 | .208 | .006 | .662 | 1 | 90 | .418 |

| 4 | .463 | .214 | .006 | .732 | 1 | 89 | .395 |

| 5 | .470 | .220 | .006 | .733 | 1 | 88 | .394 |

| 6 | .482 | .233 | .012 | .691 | 1 | 86 | .504 |

Figure 1.

Mean Body Mass Index values during methadone treatment. Data are presented for female and male methadone patients measured at Time 1 (open bars) and Time 2 (solid bars). The y-axis represents a restricted range to permit improved resolution of data for visual inspection.

Table 3.

BMI Categories

| Females | Males | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 1 | Time 2 | |

| Underweight | 3% | 0% | 5% | 5% |

| Normal | 49% | 17% | 46% | 25% |

| Overweight | 11% | 31% | 23% | 36% |

| Obese | 37% | 51% | 26% | 34% |

DISCUSSION

We observed a significant increase in BMI in the months following patients’ entry into methadone treatment. These data are consistent with prior reports of weight gain early in methadone treatment, particularly the recent report by Mysels and colleagues (2011) noting an approximate 10-pound weight gain among patients during the first six months of methadone treatment. In the present study, we observed an approximate 17.8-pound increase within the first approximately two years of treatment. These data extend prior research by including a larger sample size (n=96) and a longer period of monitoring (approximately 2 years) than was used in previous studies. Overall, these results suggest that clinically significant weight gain occurred in the months following patients’ entry into methadone treatment. Indeed, using the definition put forth by the American College of Sports Medicine (Donnelly, 2009), 65% of our patients experienced a 5% or greater increase in BMI and thus clinically significant weight gain.

We also observed significant differences in during-treatment weight gain between males and females. Female patients showed a much greater increase in BMI than males, with an increase in body weight that was almost three-fold that of males. These findings stand in contrast to a small study by Kolarzyk and colleagues (2005) who examined weight changes among 30 Polish methadone patients and found a modest weight loss in female patients vs. a modest weight gain in males. While low testosterone resulting from methadone-related HPA suppression could cause weight gain and increased fat mass in males (Bhasin, 2006), it does not account for the significantly greater increase in BMI among female patients in our study. While the exact reasons underlying the differential weight gain between male and female patients are important to examine in future studies, our finding that female patients gained on average 28 pounds (a 17.5% increase in body weight) has serious potential health implications.

Also worth noting is that the observed BMI increases during treatment were not solely a function of undernourished illicit drug abusers moving toward a healthier weight as they become stabilized in methadone treatment, which stands in contrast to prior suggestions that weight increases during treatment may be due to a malnourished state at intake (Grondbladh, 2011; Okruhlica & Slezakova, 2007). Indeed, the mean BMI for the overall group, as well as females, placed patients in the overweight category (BMIs 25.0–29.9 kg/m2) at time of intake and moved them from clinically overweight to obese (BMIs >30.0kg/m2) by Time 2.

While these data provide additional support for concerns about clinically significant weight gain among patients receiving methadone treatment, they do not isolate the mechanism involved or suggest pharmacological specificity. This was not a randomized trial and all patients received methadone as well as other numerous treatment components standard in our methadone program. Thus, it is not possible to dismantle whether the weight gain observed was a direct pharmacological effect of methadone administration specifically vs. other more general changes in behaviors (e.g., eating behavior, nutritional intake, increased access to food, physical activity levels, other drug use, increased clinical stability) that could have co-occurred with treatment intake. Similarly, it is unknown whether maintenance treatment with the partial opioid agonist, buprenorphine (Suboxone®), would also be associated with weight gain. Several prior studies have also reported that individuals in methadone maintenance report increased cravings for sugar (Bogucka-Bonikowska et al., 2002; Nolan & Scagnelli, 2007; Zador et al., 1996), which is consistent with preclinical data suggesting preferences for palatable foods following mu-agonist administration (Olszewski & Levine, 2007). It is also worth noting that in Mysels et al. (2011) report of weight gain in individuals receiving methadone treatment, the authors also followed another small group of patients receiving naltrexone (n=20), and these patients showed a similar weight gain. This suggests that there may be more general treatment-related factors other than the medication per se that may influence BMI during treatment. Regardless of the precise mechanism involved, these weight gains, which amounted to approximately 0.82 pounds per month of treatment in the overall patient group, are of potential clinical and medical significance.

Several additional limits of the present study should be noted. First, the primary limitation is that it was a retrospective review of patient charts and, while more extensive than prior studies on the topic, it still had a limited sample size and assessment history. However, the information gained from this study may aid efforts to further evaluate and address weight gain during opioid treatment. A second consideration is the possible limited generality of research done with methadone patients in Vermont (i.e. primary Caucasian opioid users in a rural setting) to more ethnically diverse samples of those residing in urban settings. However, as noted previously, our data are generally consistent with the recent study by Mysels et al. (2011), which was conducted with methadone treatment patients in New York City. Third, we limited our analyses to patients who had provided at least two BMI measurements, and our data did not capture the patients who might have left the clinic or failed to complete two BMI assessments. Concurrent medications and other health factors were also not assessed. These factors should be considered in future studies on this topic. Finally, while this study extended the monitoring period of weight changes during methadone treatment, we did not assess BMI frequently enough to characterize the timecourse with which these changes occurred. It is possible that patients’ weight gain may have continued well beyond the first two years of treatment and thus went undetected in our study. It is also possible that weight gain occurred in the initial months following intake and then subsequently plateaued. These are important questions that should be addressed in future studies, as the typical duration of patients’ methadone treatment episodes tend to be on the order of years and often decades rather than months (D’Aunno, Foltz-Murphy, Lin, 1999).

Taken together, the present study suggests that clinically significant weight gain may occur among many patients entering methadone treatment, with particularly striking increases in female patients. Although weight gain is noted as a possible side effect of methadone administration (Mallinckrodt, 2009), this study represents one of only a few that have directly examined this question. Our findings highlight the importance of ongoing monitoring of weight and other health-related changes among methadone patients during treatment. These data also support efforts to develop and implement interventions early in methadone treatment in order to help patients mitigate weight gain during treatment. Indeed, education and support around weight, nutrition, and physical activity are likely to be important treatment components for all patients entering treatment. Also important to note is that methadone patients are seen frequently during the early months of treatment and thus may be an especially convenient and receptive audience for delivery of evidence-based health interventions as part of treatment. Considering the differential changes in weight as a function of gender, educational interventions customized specifically for each gender may be warranted. Finally, the number of Americans being prescribed opioids for pain far exceeds that for addiction (5 million vs. 350,000, respectively; Parsells-Kelly et al., 2008; SAMHSA, 2011). Thus, scientific efforts to disentangle the pharmacological or other mechanisms involved in treatment-associated weight changes may extend well beyond patients receiving opioids for addiction.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this manuscript was supported in part by National Institutes of Health research grant R34DA037385, as well as Center of Biomedical Research Excellence award P20GM103644 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Ball JC, Ross A. The effectiveness of methadone maintenance treatment. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bhasin S, Cunningham G, Hayes F, Matsumoto A, Snyder P, Swerdloff R, Montori V. Testosterone therapy in adult men with androgen deficiency syndromes: An endocrine society clinical practice guideline. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2006;91(6):1995–2010. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum H, White A, Schiller M, Waldman T, Cleveland J, et al. Societal costs of prescription opioid abuse, dependence and misuse in the United States. Pain Medicine. 2011;12:657–667. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogucka-Bonikowska A, Baran-Furga H, Chmielewska K, Boguslaw H, Scinska A, Kukwa A, Przemyslaw B. Taste function in methadone maintained opioid dependent men. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2002;68:113–117. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00186-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control. Healthy weight: It’s not a diet, it’s a lifestyle. 2011 Retrieved from: http://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/adult_bmi/index.html.

- Centers for Disease Control. What causes overweight and obesity. 2012 Retrieved from: http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/adult/causes/index.html.

- D’Aunno T, Folz-Murphy N, Lin X. Changes in methadone treatment practices: Results from a panel study, 1988–1995. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1999;25(4):681–699. doi: 10.1081/ada-100101886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly JE, Blair SN, Jakicic JM, Manore MM, Rankin JW, Smith BK. Appropriate physical activity intervention strategies for weight loss and prevention of weight regain for adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(2):459–469. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181949333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gronbladh L, Ohlund L. Self-reported differences in side-effects for 110 heroin addicts during opioid addiction and during methadone treatment. Heroin Addiction and Related Clinical Problems. 2011;13(4):5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RE, Chutaupe MA, Strain EC, Walsh SL, Stitzer ML, et al. A comparison of levomethadyl acetate, buprenorphine, and methadone for opioid dependence. New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;343(18):1290–1297. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011023431802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolarzyk E, Pach D, Wojtowicz B, Szpanowska-Wohn A, Szurkowska M. Nutritional status of the opiate dependent persons after 4 years of methadone maintenance treatment. Przeglad Lekarski. 2005;62(6):373–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan A, Luborsky L, Cacciola J, Griffith J, Evans F, Barr H, O'Brien C. New data from the Addiction Severity Index. Reliability and validity in three centers. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disorders. 1985;173(7):412–423. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198507000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mysels DJ, Sullivan MA. The relationship between opioid and sugar intake: Review of evidence and clinical applications. Journal of Opioid Management. 2010;6(6):445–452. doi: 10.5055/jom.2010.0043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mysels D, Vosburg S, Benga I, Levin F, Sullivan M. Course of weight change during naltrexone vs. methadone maintenance for opioid-dependent patients. Journal of Opioid Management. 2011;7(1):47–53. doi: 10.5055/jom.2011.0048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Library of Medicine. Daily Med: methadone (methadone hydrochloride) concentrate drug label [document on internet] 2011 Available from: http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/lookup.cfm?setid=808a9d0b-720b-4034-a862-5122ff514608.

- Nolan L, Scagnelli L. Preference for sweet foods and higher body mass index in patients being treated in long-term methadone maintenance. Substance Use and Misuse. 2007;42:1555–1566. doi: 10.1080/10826080701517727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okruhlica L, Slezakova S. Weight gain among the patients in methadone maintenance program as come-back to population norm. Cas Lek Cesk. 2008;147(8):426–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olszewski P, Levine A. Central opioids and consumption of sweet tastants: when reward outweighs homeostasis. Physiology and Behavior. 2007;97:506–512. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsells-Kelly J, Cook SF, Kaufman DW, Anderson T, Rosenberg L, Mitchell AA. Prevalence and characteristics of opioid use in the US adult population. Pain. 2008;138:507–513. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasco JA, Holloway KL, Dobbins AG, Kotowicz MA, Williams LJ, Brennan SL. Body mass index and measures of body fat for defining obesity and underweight: A cross-sectional, population-based study. BMC Obesity. 2014;1(1):9. doi: 10.1186/2052-9538-1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajs J, Petersson A, Thiblin I, Olsson-Mortlock C, Fredriksson A, Eksborg S. Nutritional status of deceased illicit drug addicts in Stockholn, Sweden—a longitudinal medicolegal study. The Journal of Forensic Science. 2004;49(2):1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Corral A, Somers VK, Sierra-Johnson J, Thomas RJ, Collazo-Clavell ML, Korinek J, Lopez-Jimenez F. Accuracy of body mass index in diagnosing obesity in the adult general population. International Journal of Obesity. 2008;32(6):959–966. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selzer M. The Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test: The quest for a new diagnostic instrument. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1971;127(12):1653–1658. doi: 10.1176/ajp.127.12.1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stotts AL, Dodrill DC, Kosten TR. Opioid dependence treatment: Options in pharmacotherapy. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 2009;10(11):1727–1740. doi: 10.1517/14656560903037168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Trends in the Use of Methadone and Buprenorphine at Substance Abuse Treatment Facilities: 2003 to 2011. 2011 Retrieved from: http://www.samhsa.gov/data/2k13/NSSATS107/sr107-NSSATS-BuprenorphineTrends. htm. [PubMed]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. SAMSHA; 2011. Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Addiction: 2010 State Profiles. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zador D, Lyons Wall P, Webster I. High sugar intake in a group of women on methadone maintenance in southwestern Sydney, Australia. Addiction. 1996;91(7):1053–1061. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]