Abstract

Tremendous resources are being invested all over the world for prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of various types of cancer. Successful cancer management depends on accurate diagnosis of the disease along with precise therapeutic protocol. The conventional systemic drug delivery approaches generally cannot completely remove the competent cancer cells without surpassing the toxicity limits to normal tissues. Therefore, development of efficient drug delivery systems holds prime importance in medicine and healthcare. Also, molecular imaging can play an increasingly important and revolutionizing role in disease management. Synergistic use of molecular imaging and targeted drug delivery approaches provides unique opportunities in a relatively new area called `image-guided drug delivery' (IGDD). Single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) is the most widely used nuclear imaging modality in clinical context and is increasingly being used to guide targeted therapeutics. The innovations in material science have fueled the development of efficient drug carriers based on, polymers, liposomes, micelles, dendrimers, microparticles, nanoparticles, etc. Efficient utilization of these drug carriers along with SPECT imaging technology have the potential to transform patient care by personalizing therapy to the individual patient, lessening the invasiveness of conventional treatment procedures and rapidly monitoring the therapeutic efficacy. SPECT-IGDD is not only effective for treatment of cancer but might also find utility in management of several other diseases. Herein, we provide a concise overview of the latest advances in SPECT-IGDD procedures and discuss the challenges and opportunities for advancement of the field.

Keywords: Cancer, Chemotherapy, Image-guided drug delivery, Molecular imaging, Single-photon emission computed tomography, Theranostics

INTRODUCTION

Efficiency is one of the core values of today's clinical environment. In this context, molecular imaging has become an indispensable tool that could change the way the medical community thinks and practices, not only for diagnostic purposes but also for therapy as well (1–3). The last three decades have witnessed unprecedented increase in the number of imaging technologies and their applications in clinical context (4–6). Molecular imaging approaches now attempt to non-invasively measure biological processes at the cellular level in living subjects by using suitable molecular probes, thereby providing the potential for understanding the integrative biology, early detection and characterization of several diseases, and assessment of treatment regimens (2). A relatively newer and increasingly imperative role played by molecular imaging is in the field of `image-guided drug delivery' (IGDD) (7–10). The concept of IGDD is now rapidly maturing with promises for personalized therapy in the foreseeable future.

The conventional systemic drug delivery approaches suffer from properties of poor pharmacokinetics and inappropriate biodistribution of therapeutic drugs leading to toxicity issues (7, 10–12). Also, many drugs cannot show the desired therapeutic efficacy due to their rapid clearance from the biological system (13). Despite persistent pursuit by the medical community over the past several decades, efficient delivery of a drug to its designated site of action is still facing several clinical challenges, especially in cancer chemotherapy (13). In many cases, owing to the absence of an effective and accurate tool for monitoring the drug delivery, many agents that have been shown to be highly effective in vitro are often less effective when delivered in vivo. The novel strategy of IGDD involves an optimized delivery of a therapeutic agent and an imaging probe simultaneously to the disease site, thereby providing a “visibility” in drug delivery during the course of therapy and thus has the potential to overcome the above limitations.

Successful IGDD is based on achieving two major objectives. The first objective is to allow early detection of molecular events indicative of a disease process by developing suitable imaging probes. The developed imaging probes must also possess the capability to monitor the efficacy of therapeutic intervention. Significant progress has been reported to achieve the goal of early detection and monitoring of several diseases, including cancer (14). The second objective is to develop efficient molecular vehicles which can not only take the therapeutic drugs precisely to the desired site but also stimulate sustained release of these drugs. Targeted drug delivery followed by a controlled release at the disease site improves bioavailability of the drug by avoiding its premature degradation and enhancing tumor uptake. This approach also maintains drug concentration within the therapeutic limit by controlling the drug release rate, and minimizing side effects (13). The IGDD strategies involving synergistic combination of diagnostic imaging and targeted therapy have been termed as “theranostics” and are important moves toward achieving simultaneous diagnosis and therapy of diseases.

Currently, several non-invasive imaging modalities are being used in biomedical and clinical settings, which include magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT), positron emission tomography (PET), single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), optical imaging, and ultrasonography (1, 2, 15–18). Among these, SPECT, PET, and optical imaging are regarded as quantitative or semi-quantitative imaging modalities, whereas CT, MRI, and ultrasonography are normally used for acquisition of anatomical information. The advantages and limitations of these imaging modalities have been elaborately discussed in several review articles (1, 2, 15–17). Synergistic advantages over any single modality can be achieved by combining multiple molecular imaging techniques and therefore this approach is gaining popularity in the recent times (16, 17). However, the concept of multimodality imaging is relatively new and most IGDD procedures are reported using any single imaging modality.

Among the various imaging modalities, SPECT and PET are commonly used for IGDD procedures. The recent developments in PET-IGDD have been summarized in a recent review (19). Herein, we attempt to provide a concise overview of the SPECT-IGDD approaches using various multifunctional drug carriers. The outcomes of these studies and the advantages and limitations of SPECT imaging are discussed. Exciting and innovative prospects of these recent developments are highlighted to offer a fascinating sight into the future.

SINGLE-PHOTON EMISSION COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY

SPECT is a nuclear imaging technique using γ-rays that enables assessment of biochemical changes and levels of molecular targets within a living subject (20, 21). For the last few decades, SPECT is the leading nuclear imaging technique due to the extensive use of 99mTc (t½ = 6 h), which can be conveniently obtained from 99Mo/99mTc generators (22). This radioisotope has played a pivotal role in the field of nuclear medicine due to its excellent nuclear decay characteristics and cost-effective availability (22, 23). Technetium-99m is known as the “work-horse” of nuclear medicine and is used for >80% of all diagnostic nuclear imaging procedures (22). It is pertinent to mention that more than 30 million patient studies worldwide (50% of which are in the United States alone) are performed annually using 99mTc-based radiopharmaceuticals (22). Several other radionuclides such as 123I (t½ = 13.3 h), 111In (t½ = 2.8 d), 67Ga (t½ = 3.26 d), etc. have also been used for SPECT imaging (21, 24). For SPECT imaging, a gamma camera is used which rotates around the testing subject to capture data from various positions to get a tomographic reconstruction. The radioisotopes which are used for SPECT imaging are generally categorized into two types: (a) the ones which are used for diagnosis only and (b) others which can be used diagnosis as well as therapy (25). The commonly used radioisotopes for SPECT imaging and their decay characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Physical characteristics of some radionuchdes used for clinical SPECT imaging

| Radionuclide | Half-life | Mode of decay@ | Principal γ-component energy in keV (% abundance) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 99mTc | 6.0 h | IT | 140.5 (88.9) |

| 123I | 13.3 h | EC | 159.0 (82.8) |

| 67Ga | 3.3 d | EC | 93.3 (38.3) |

| 111In | 2.8 d | EC | 245.4 (94.2) |

| 201T1 | 72.9 h | EC | 167.4 (10.0) |

Only principal decay mode is mentioned; EC indicates decay by electron capture; IT indicates decay by isomeric transition.

Though SPECT technology has been widely relied upon over the last few decades, only a limited number of new SPECT radiopharmaceuticals have been developed in the recent times compared to large number of interesting PET tracers which are continuously being reported from different parts of the world for clinical diagnosis (26–29). The major reasons for the decreasing interest in SPECT are its lower sensitivity and resolution compared to PET. Despite these limitations, SPECT still remains the most commonly used nuclear imaging modality in clinics all over the world (20, 30). Considering the unparalleled nuclear characteristics of 99mTc (the most important SPECT radioisotope), its cost-effective accessibility from 99Mo/99mTc generators and availability of relatively larger number of SPECT scanners worldwide, the SPECT technology is likely to retain its clinical impact and play a well-defined role in the field of molecular imaging in the foreseeable future (30, 31). However, in order to remain competitive in clinical context, SPECT has to maintain its advantages and continue to exploit recent technologies to improve diagnostic capabilities. In this regard, the recent advances in development of SPECT scanners are able to provide higher spatial and temporal resolution, higher detection efficiency and greater quantitative accuracy (30, 32, 33). Such developments would have a direct impact on clinical and research practices to influence the future of molecular SPECT imaging.

CARRIERS FOR SPECT-IGDD

A systematic approach to SPECT-IGDD mandates effective procedures for targeting, delivery, activation, and monitoring of the entire process. A large number of multifunctional drug carriers such as liposomes, micelles, microparticles, nanoparticles, microbubbles, dendrimers, copolymers, etc. have been developed in recent years (10, 13, 34, 35). These drug carriers have the potential to be non-toxic and less immunostimulatory, while being adaptable for alteration and taking different types of drug payloads to the targeted lesions. These drug carriers also possess the advantageous ability to be easily radiolabeled with suitable SPECT radionuclides for theranostic purposes. With the latest innovations in materials science, organic chemistry, functional genomics, and proteomics, smart drug delivery systems have now been developed which are biodegradable, biocompatible, can precisely target the disease site, and are stimulus-responsive towards drug release (10, 13, 34, 35). However, circumventing the biological barriers to the delivery of therapeutics into tumor cells is still a major challenge.

Currently, two different strategies are used for loading drugs onto carrier systems (36). In the first approach, drugs are directly conjugated with a targeting ligand. A major limitation of this approach is that the drugs might lose their therapeutic efficacy due to chemical modification and conjugation with the targeting agent. Also, the drugs are exposed to the biological environment and might get degraded during the course of transit to the disease site. These limitations can be avoided in another approach, wherein drugs are encapsulated in high capacity drug carriers such as nanoparticles (13, 35). Such drug delivery systems result in enhanced therapeutic effects by protecting entrapped drugs from degradation during their delivery. In both approaches, the drug delivery platforms are either directly conjugated to targeting ligands such as antibodies, aptamers, peptides, proteins, etc., or are suitably modified for interaction with specific adapters that are conjugated with the targeting ligands (13). One representative example for these adapters is streptavidin/biotin, which is explored in many cases for binding drug carriers to targeting ligands (37).

In SPECT-IGDD procedures, the delivery of the drug to the target tissue can be achieved by both passive and active targeting (38). Passive targeting is based on the ability of the drug carriers to remain in blood circulation for a long time, accumulate in pathological sites with compromised vasculature via the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, and enable drug delivery (38). Especially, nanosized drug carriers match the length scales of most tumor interendothelial junctions facilitating EPR-mediated localization into poorly accessible areas of the tumor (38). Active targeting can be achieved by attaching specific ligands to the surface of drug carriers to distinguish and bind pathological cells (38). It must be mentioned here that simply relying on EPR-mediated passive targeting is not the most ideal approach for drug delivery as therapeutic concentrations can be much lower than optimal at the tumor site. Combination of both passive and active targeting is generally more desirable for maximizing therapeutic efficacy. After targeting, the drug carriers might be internalized by tumor cells via receptor-mediated endocytosis/phagocytosis, resulting in increased drug concentration in tumor tissues (38).

SPECT-IGDD procedures are not just limited to delivery of chemotherapeutic drugs. In certain cases, the targeting carriers are radiolabeled with a suitable therapeutic radioisotopes such as 188Re (t½ = 17 h), 166Ho (t½ = 26.8 h) or 177Lu (t½ = 6.7 d) (Table 2) (25). These radioisotopes act as a drug for radiation therapy and also as a probe for monitoring the efficacy of the therapeutic approach. Various drug carrier systems have been radiolabeled with different γ-emitting radioisotopes for SPECT-IGDD, some of which are summarized in Table 3 and discussed in the following text.

Table 2.

Physical characteristics of some radionuclides which can be used for SPECT image-guided radiotherapy

| Radionuclide | Half-life | Mode of decay@ | α/β− particle energy (keV)# | Principal γ-component energy in keV (% abundance) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 47Sc | 3.3 d | β−, γ | 600.1 | 159.4 (68.0) |

| 67Cu | 61.8 h | β−, γ | 577.0 | 184.6 (48.7) |

| 77As | 38.8 h | β−, γ | 682.9 | 239.0 (1.6) |

| 105Rh | 35.4 h | β−, γ | 567.0 | 318.9 (19.2) |

| 109Pd | 13.7 h | β−, γ | 1115.9 | 88.0 (3.6) |

| 111Ag | 7.4 d | β−, γ | 1036.8 | 342.1 (6.7) |

| 131I | 8.0 d | β−, γ | 970.8 | 364.5 (81.2) |

| 133Xe | 5.2 d | β−, γ | 427.4 | 81.0 (37.1) |

| 142Pm | 19.1 h | β−, γ | 2162.3 | 1575.6 (3.7) |

| 149Pm | 53.1 h | β−, γ | 1071.0 | 285.9 (2.8) |

| 153Sm | 46.3 h | β−, γ | 808.4 | 103.2 (28.3) |

| 159Gd | 18.5 h | β−, γ | 970.6 | 58.0 (26.2) |

| 165Dy | 2.3 h | β−, γ | 1286.2 | 94.7 (3.6) |

| 166Ho | 26.8 h | β−, γ | 1854.5 | 80.6 (6.2) |

| 175Yb | 4.2 d | β−, γ | 470.0 | 396.3 (6.5) |

| 177Lu | 6.7 d | β−, γ | 498.2 | 208.4 (11.0) |

| 186Re | 90.6 h | β−, γ | 1069.5 | 137.2 (8.6) |

| 188Re | 16.9 h | β−, γ | 2120.4 | 155.0 (14.9) |

| 194Ir | 19.3 h | β−, γ | 2246.9 | 328.4 (13.0) |

| 198Au | 2.7 d | β−, γ | 1372.5 | 411.8 (95.5) |

| 199Au | 3.1 d | β−, γ | 452.6 | 158.4 (36.9) |

| 211At | 7.2 h | α, γ | 5982.4 | 687.0 (0.3) |

| 212Bi | 60.6 min | α, γ | 6207.1 | 727.2 (11.8) |

| 213Bi | 45.6 min | α, γ | 5982.0 | 439.7 (27.3) |

| 223Ra | 11.4 d | α, γ | 5979.3 | 269.4 (13.6) |

| 225Ac | 10.0 d | α, γ | 5935.1 | 99.7 (3.5) |

Only principal decay mode is mentioned;

For β− particles, maximum β− energy is mentioned

Table 3.

Representative examples of different drug delivery systems that were radiolabeled with γ-emitting radionuclides for potential SPECT-IGDD applications.

| Drug carrier | Target | Targeting ligand | Therapeutic agent | SPECT isotope | Disease model | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copolymer | None (passive targeting) | None (passive targeting) | Paclitaxel | 125I | Human ovarian cancer | (45) |

| Dendrimer | Folate receptor | Folic acid | None | 99mTc | Human epidermoid cancer | (53) |

| Micelle | Glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78) | GRP78 binding peptide (GRP78BP) | None | 111In | Human gastric cancer | (61) |

| Liposome | None (passive targeting) | None (passive targeting) | Dexamethasone | 111In | Human lung cancer | (81) |

| Microparticle | None (passive targeting) | None (passive targeting) | Metronidazole | 131I | Helicobacter pylori infection | (86) |

| Gold nanospheres | Tyrosine kinase receptors | TNYL-RAW peptide | Doxorubicin | 111In | Ovarian cancer | (105) |

| Carbon nanotube | None (passive targeting) | None (passive targeting) | Hydroxycamptothecin | 99mTc | Hepatic cancer | (123) |

| Polymeric nanoparticles | Folate receptors | Folic acid | Doxorubicin | 123I | Human cervical cancer | (137) |

Drug delivery using copolymers and polylysine based carriers

Over the last several years, a large number of drug carriers have been developed using polymeric materials which are chemically inert, free from leachable impurities and biodegradable (39–41). Some polymeric materials that are currently being used or studied for drug delivery include poly(vinyl alcohol), poly(N-vinyl pyrrolidone), polyacrylamide, polylysine, polyethylene glycol, polystyrene maleic anhydride copolymer, [N-(2)hydroxypropyl]-methacrylamide copolymer (HPMA), and poly(L-glutamic acid) (39–41). Among various polymeric carriers studied, HPMA copolymers and their drug conjugates have been most intensively investigated over last several years and some of the HPMA copolymer drug conjugates have now entered clinical trials (39). HPMA copolymer drug conjugates have distinct advantages over the original therapeutics, which include good biocompatibility, high aqueous solubility and bioavailability, enhanced drug retention time, low systemic toxicity, and increased therapeutic efficacy (39–41). However, certain other polymeric drug carriers might have issues related to biocompatibility and drug loading efficiency. Also, the delivery of drug payload in a highly regulated and site-specific manner to the disease site has not yet been fully achieved using polymeric carriers (39–41).

The development of bone-targeting drug delivery system based on HPMA copolymer was reported by Wang et al (42). The drug delivery systems help to increase the osteotropicity of drugs and improve their pharmacokinetic profile and efficacy for treatment of various musculoskeletal diseases. Targeting moieties such as Alendronate (a bisphosphonate) and D-aspartic acid octapeptide (D-Asp8) were attached to the drug carrier so that it can strongly bind the bone surface. The HPMA copolymer was radiolabeled with 125I and administered intravenously in normal BALB/c mice. In vivo SPECT imaging and biodistribution studies demonstrated high uptake (~12 %ID/g) of bone targeting HPMA copolymer by the entire skeleton and especially at the high bone turnover sites. The authors also evaluated the influence of molecular weights of HPMA copolymer-D-Asp8 conjugates on enhanced bone uptake and found that higher molecular weight polymers demonstrated increased bone uptake due to prolonged circulation half-life of the conjugate. However, bone selectivity was lowered on increasing the molecular weight of the HPMA copolymer conjugates. Despite high bone uptake, insufficient distribution of the delivery system to soft tissues was observed which might cause substantial in vivo side effects and therefore further optimization of the conjugation strategy would be required before this approach can be translated to clinical settings. In a different study, Buckway et al reported the synthesis of 111In-labeled HPMA copolymers conjugated with short peptide sequences targeting pancreatic tumors (43). The authors used cyclic RGD (cRGD) peptide and KCCYSL peptide to target integrin αvβ3 expression and HER2 receptors, respectively. The delivery of macromolecules to pancreatic cancer is generally obstructed by a dense extracellular matrix composed of hyaluronic acid, smooth muscle actin and collagen fibers (44). Hyaluronic acid causes a high intratumoral fluidic pressure which precludes diffusion and penetration of drug conjugates into the pancreatic tumor. Therefore, hyaluronidase enzymes were used to break hyaluronic acid resulting in lowering of pressure (44). In vivo SPECT imaging and biodistribution studies revealed that enhanced tumor targeting (maximum tumor uptake of ~5 %ID/g) with peptide conjugated HPMA copolymers was achieved after treatment with hyaluronidase. The tumor uptake in hyaluronidase treated tumors was 2–3 times greater than non-hyaluronidase treated tumors. The authors concluded that this procedure would help the localization of radiolabeled HPMA copolymers containing chemotherapeutic drugs into the tumor for image-guided therapy.

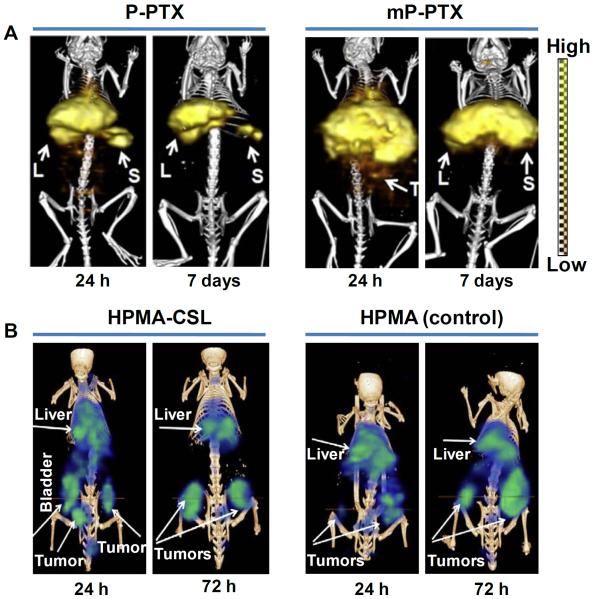

Recently, Zhang et al reported the synthesis of a new-generation multiblock backbone biodegradable HPMA copolymer with relatively high molecular weight (~335 kDa) (45). The behavior of paclitaxel (PTX) conjugated high molecular weight HPMA copolymer (mP-PTX) was compared with conventional HPMA copolymer-PTX conjugate (P-PTX) having molecular weight of 48 kDa. In vitro studies on human ovarian carcinoma (A2780) cells demonstrated that the high molecular weight HPMA copolymer drug conjugate had similar cytotoxic effect as free PTX and P-PTX. The HPMA copolymer drug conjugates were radiolabeled with 125I and in vivo SPECT/CT imaging and biodistribution studies were carried out in mice bearing orthotopic A2780 tumors, which revealed that mP-PTX was cleared more slowly from the blood than commercial PTX and P-PTX formulations (Figure 1A). Biodegradability as well as removal of mP-PTX from the body was also demonstrated from these studies. Different formulations of drug conjugates were intravenously injected (at a single dose of 20 mg equivalent PTX/kg) into mice bearing A2780 tumors and it was shown that tumors in the mP-PTX treated group grew more slowly than those treated with saline, free PTX, and P-PTX. Also, mice treated with mP-PTX had no obvious ascites formation and body-weight loss. The promising results obtained in this study suggests that biodegradable high molecular HPMA copolymers hold promise for image-guided delivery of chemotherapeutic drugs. However, non-target accumulation, particularly in the liver and spleen, might obstruct the detection of nearby metastatic lesions thereby decreasing diagnostic effectiveness. In order to circumvent this limitation, Shi et al reported the development of HPMA copolymers with cathepsin S susceptible linkers (CSLs) that cleave in the presences of cathepsin S, to reduce the non-target accumulation of HPMA copolymers in mononuclear phagocyte (MPS) system (46). Cathepsin S is a lysosomal protease that is selectively and highly expressed in MPS tissues (47). Three different CSLs with linking groups of various lengths (0, 6 and 13 atoms) were conjugated to HPMA copolymers and rapid cleavage of longest linking group (13 atoms) was observed when challenged with cathepsin S in vitro. The HPMA copolymers were radiolabeled with 177Lu and intravenously injected in human pancreatic (HPAC) tumor bearing mice. In vivo SPECT imaging and biodistribution studies showed that CSL incorporated HPMA copolymers showed higher levels of excretion and decrease in long-term hepatic and splenic retention compared to the non-cleavable control (Figure 1B). The maximum tumor uptake (~5 %ID/g) was observed at 5 h post-injection. Contrary to the results observed in vitro, the length of the linking group of CSLs did not significantly impact non-target clearance in vivo. Nevertheless, the authors could demonstrate that CSLs, irrespective of their length, could substantially improve the non-target clearance of HPMA copolymers and this feature might aid in utilization of such materials for image-guided therapy.

Figure 1.

SPECT image-guided tumor targeting using polymer-based carrier. (A) SPECT/CT imaging of mice bearing orthotopic A2780 human ovarian carcinoma after intravenous injection of 125I-labeled P-PTX or 125I-labeled mP-PTX at 24 h and 7 days, post-injection. (L = liver; S = spleen; T = tumor). Adapted from reference (45) with permission. (B) SPECT/CT imaging of mice bearing human pancreatic HPAC tumor after intravenous injection of 177Lu-labeled CSL incorporated HPMA (HPMA-CSL) or 177Lu-labeled HPMA (control) at 24 h and 72 h post-injection. Adapted from reference (46) with permission.

A different strategy was reported by Patil et al. for imaging human prostate cancer xenografts using radiolabeled polymer-drug conjugates (48). In this study, pre-targeting with a bispecific monoclonal-antibody and targeting with 99mTc or 111In-labeled diethylene triamine penta acetic acid (DTPA)-succinyl polylysine were used for visualization of tumors with high contrast. Also, this approach would minimize delivery of therapeutic drugs to non-targeted organs, thereby minimizing the side effects. Radiolabeled polymer was injected intravenously at 24 h after antibody pre-targeting. SPECT/CT imaging enabled detection of very small (1–2 mm) prostate cancer lesions in vivo within 1-3 h post-injection of radiolabeled polymer. Also, most of the radioactivity associated with the polymers cleared from the blood within 3 h. This work was extended by the same group of authors for highly target-specific delivery of polymers conjugated with chemotherapeutic agents to maximize therapeutic efficacy while minimizing non-target bystander toxicity (49). In this study, an anti-cancer drug, doxorubicin (DOX) was conjugated to N-terminal DTPA-modified polyglutamic acid and administered in mice bearing HER2-positive human mammary carcinoma (BT-474) xenografts after pre-targeting with bispecific anti-HER2-affibody anti-DTPA-Fab complexes. The BT-474 lesions were visualized by in vivo SPECT imaging with 99mTc labeled DTPA-succinyl-polylysine polymers. Therapeutic efficacy of this approach using DOX-conjugated polymer in mice was equivalent to treatment with DOX alone. However, total body weight loss was not observed in mice treated with DOX-conjugated polymers even when the drug concentration in the polymer was three times of the doxorubicin equivalent maximum tolerated dose. The pre-targeted therapeutic strategies adopted in these studies are highly target specific, delivering very high specific activity reagents that might aid in development of polymer based theranostic platforms.

Drug delivery using dendrimers

Dendrimers are a relatively newer class of polymeric materials which are generally described as hyper-branched macromolecules with tree-like branching architecture and compact spherical geometry in solution (50). Dendrimers are known for possessing certain unique properties such as uniform size, high degree of branching, water solubility, controlled architecture allowing multivalent attachment possibilities, well-defined molecular weights, available internal cavities, and biocompatibility, which make them attractive for biological and drug delivery applications. Despite excellent attributes of dendrimer based carriers, controlling the release kinetics of the encapsulated drug is problematic and depends on several factors such as the lipophilicity and size of the drug, generation number of the dendritic carrier, and surface modification (50, 51).

Parrott et al. reported the synthesis of a series of aliphatic polyester dendrons with p-toluenesulfonyl ethyl (TSe) ester core (52). A tridentate bis(pyridyl)amine ligand was introduced at the dendrimer core using amidation chemistry to form complexes with 99mTc. In vivo dynamic SPECT imaging and biodistribution studies in rats revealed that the radiolabeled dendrimers were rapidly eliminated from the bloodstream by renal route with negligible non-specific binding (Figure 2). This preliminary study provided the foundation for using radiolabeled dendrimers for SPECT imaging. The synthesis of poly(amidoamine) dendrimers conjugated with folic acid (PAMAM-FA) was reported by Zhang et al (53, 54). The dendrimer conjugate was radiolabeled with 99mTc and injected intravenously in mice bearing human epidermoid carcinoma (KB) xenografts. In vivo SPECT imaging and biodistribution studies showed that the tumor uptake of the radiolabeled dendrimer increased with time and was ~15 %ID/g at 6 h post-injection. Also, significant liver uptake and blood retention were observed even at 6 h post-injection, which is expected for radiolabeled macromolecules. The high kidney uptake (~45 %ID/g) could be attributed to the high abundance of folate receptors in the proximal tubules of the kidneys. Uptake in all other organs was almost negligible. This same group demonstrated that PEGylation of PAMAM-FA conjugate improved the tumor targeting and maximum uptake of ~10 %ID/g was observed at 6 h post-injection of the radiolabeled dendrimer conjugate (53). The work was further extended in order to reduce the high kidney uptake observed in case of PAMAM-FA conjugate (55). This could be achieved by conjugating the dendrimer with avidin instead of folic acid. Biodistribution studies in normal mice showed much lower kidney uptake (~3 %ID/g) at 6 h post-injection demonstrating the effectiveness of this approach. These preliminary studies benchmark the behavior of dendrimers in vivo and enable further investigations of their targeting by conjugation with suitable biomolecules.

Figure 2.

SPECT image-guided biodistribution study using dendrimer based carrier. Dynamic SPECT images were taken from time 0 to 15 min, after intravenous injection of 99mTc-labeled dendrimer in male Copenhagen rats (H = heart, L = liver, K = kidney, B = bladder). Adapted from reference (52) with permission.

In all these studies, development of only imaging strategies using dendrimer-based platforms have been described without direct relation to drug delivery. However, there are several other reports on utility of dendrimer-based carriers for drug delivery (56). Therefore, it was expected that tracking disease progression would be analogous to tracking drug delivery using dendrimer-based carriers. This hypothesis might also be valid for other drug carrier systems described below.

Drug delivery using micelles

A micelle is an aggregate of surface-active molecules dispersed in a liquid colloid and generally consists of two distinct regions: a hydrophilic head-group and a hydrophobic tail (57). The inherent and modifiable properties of micelles make them particularly well suited for drug delivery purposes (57). Miceller structures which are relatively small and uniform, can be prepared from a variety of amphiphilic materials to increase solubility of hydrophobic molecules, and achieve multifunctionality in a single structure. When tagged with suitable contrast agents, these systems can also be used for molecular imaging as well as image-guided drug delivery. In particular, polymeric micelles have demonstrated good biocompatibility and enable effective encapsulation of various poorly soluble agents, and are therefore used most extensively for preclinical and clinical studies (57). However, certain issues related to low drug loading efficiency and in vivo stability of the micellar carriers has not yet been fully resolved (58).

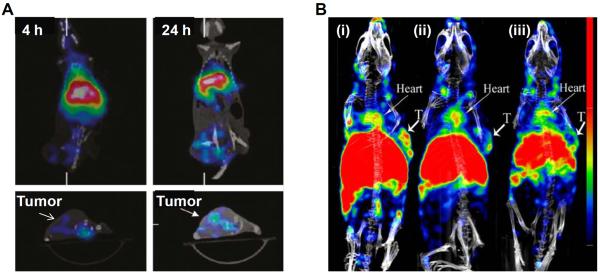

The synthesis of amphiphilic diblock copolymer and its radiolabeling with 111In was reported by Hoang et al (59). The radiolabeled micelles were intravenously injected in normal mice in order to enable real-time and non-invasive evaluation of the pathway and fate of block copolymer micelles in vivo, using microSPECT/CT imaging. Radiolabeled micelles remained in blood circulation for a long time and accumulated mainly in liver (14 ± 3 %ID/g) and spleen (27 ± 6 %ID/g), possibly, due to clearance via MPS, commonly observed with such macromolecular formulations. Though, tumor targeting or drug delivery was not reported, this preliminary study provided insight on the distribution of the micellar assemblies in vivo. In another study, Peng et al. reported the synthesis of multifunctional micelles loaded with the near-infrared (NIR) dye (IR-780 iodide) and radiolabeled with 188Re for multimodality imaging (60). The radioisotope 188Re itself can not only aid in SPECT imaging but is also useful for radiation therapy. In vivo microSPECT/CT imaging and biodistribution studies in mice bearing human colon cancer (HCT-116) xenografts revealed that radioactivity accumulated in the spleen, liver, and tumor at 24 h post-injection of radiolabeled micelle and the maximum tumor uptake was 2-3 %ID/g (Figure 3A). The accumulation of the radiolabeled micelle in tumor took place by EPR effect. The tumor uptake can be improved by conjugating with suitable targeting ligands and this approach might find utility in development of micellar agents for multimodality imaging and drug delivery.

Figure 3.

SPECT image-guided tumor targeting using micelle based carrier. (A) MicroSPECT/CT imaging of mice bearing human colon cancer (HCT-116) xenografts after intravenous injection of 188Re-labeled micelles at 4 h and 24 h, post-injection. Adapted with permission from reference (60) with permission. (B) SPECT/CT imaging of mice bearing human glioblastoma (U87MG) xenografts tumor 24 h after intravenous administration of (i) 111In-labeled micelle-octreotide (targeted), (ii) 111In-labeled micelle-octreotide plus excess of cold micelle-octreotide (blocking) and (iii) 111In-labeled micelle (non-targeted). Arrows indicate tumors (T = tumor). Adapted from reference (62) with permission.

In a recent study, Cheng et al. have reported the synthesis of polymeric micelles targeting glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78), which is a biomarker for gastric cancers (61). The polymeric micelle was conjugated with GRP78 binding peptide (GRP78BP) and radiolabeled with 111In. The radiolabeled micelle was intravenously injected in mice bearing human gastric cancer (MKN45) xenografts and the in vivo distribution was monitored by SPECT imaging at 24 h post-injection. The results revealed that tumor uptake was 2-3 times higher after the administration of 111In-labeled micelles conjugated with GRP78BP peptide compared with non-targeted 111In-labeled micelles, demonstrating the suitability of this peptide in targeting gastric cancer. In a similar study, Hong et al reported the synthesis of 111In-labeled polymeric micelles conjugated with octreotide for neuroendocrine tumor detection (62). In vivo SPECT imaging and biodistribution studies in U87MG tumor bearing mice showed higher uptake the radiolabeled micelle conjugated with the peptide compared to the non-targeted micelle (Figure 3B). Also, the authors demonstrated the specificity of targeting by `blocking' studies. The high tumor accumulation of the radiolabeled micelle conjugated with octreotide was significantly reduced after co-injection of an excess amount of octreotide (Figure 3B). In another interesting study, Maldonado et al. reported the synthesis quantum dot-filled micelles which could be radiolabeled with 99mTc for dual modality SPECT-optical imaging (63). It was demonstrated that Cisplatin (a widely used anticancer drug) could be generated from a Pt(IV) complex by exposure to visible light in the presence of water soluble quantum dot-filled micelle. These studies show the potential of micellar systems for biological imaging, tumor diagnosis, drug delivery and anticancer applications.

Drug delivery using liposomes

Liposomes are closed bilayer phospholipid systems enclosing an aqueous environment and are being extensively used for drug delivery (64). In fact, the pioneering work of large numbers of liposome researchers over last several decades has led to important technological advances in drug loading, targeted drug delivery and stimulated drug release using liposomal carriers (64, 65). Liposomes are composed of naturally occurring components and offer innumerable opportunities for composition and surface modifications which make them extremely flexible drug carriers. However, low in vivo stability, rapid clearance from the biological system, uptake by the reticuloendothelial system, need for extensive surface modification for targeted delivery and short shelf-life are some of the major limitations of the liposomal carriers for drug delivery (64, 65). Generally, the size of liposomes varies in the range from 50 nm to several micrometers, with the most stable and useful size as a drug carrier being in the 90–250 nm (64). In particular, several liposomal formulations in the size range of 90–100 nm are clinically approved for drug delivery (64, 65). Due to the wide variation in sizes of liposomal carriers, they could not be categorized as `microparticles' or `nanoparticles' (as discussed in the subsequent sections) and have been dealt here separately.

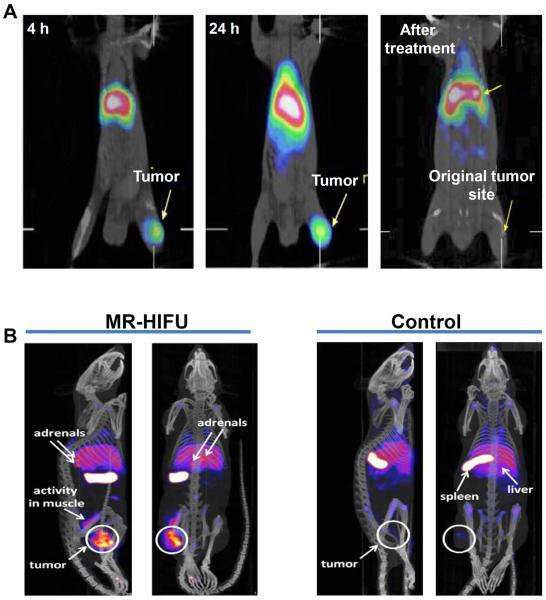

The synthesis of PEGylated N,N-bis (2-mercaptoethyl)-N′,N″-diethylethylenediamine (BMEDA)-liposomes for targeting colon carcinoma by EPR effect was reported by Chen et al (66). The micelles were radiolabeled with 188Re and administered by intraperitoneal route in mice bearing colon carcinoma (C26) ascites. The radiolabeled micelles were determined to be highly stable in saline and rat serum at 37 °C for over 72 h. In vivo SPECT and biodistribution studies revealed that tumor uptake of radiolabeled PEGylated liposomes increased progressively over time and a maximum uptake of ~6 %ID/g was observed at 24 h after injection. Pharmacokinetics studies revealed that the PEG modification of liposomes increased its circulation life-time significantly, thereby, increasing the tumor uptake (66, 67). This work was extended by the same group and a chemotherapeutic drug (DOX) was incorporated in PEGylated BMEDA-liposomes and radiolabeled with 188Re (68). The antitumor effect of the radiolabeled micelle containing DOX was studied and it was revealed that the bimodality radiochemotherapeutics of 188Re-labeled and DOX-loaded liposome showed better mean tumor growth inhibition rate and longer median survival time than those treated with radiotherapeutics of 188Re-labeled liposome (without DOX) and chemotherapeutics of DOX-loaded liposome (without 188Re labeling). In vivo SPECT/CT imaging showed a significant uptake (SUV 4.70 ± 0.36) of 188Re-labeled liposome at 24 h post-injection in mice bearing colon (C26) tumors (Figure 4A). No uptake in the original tumor inoculation site at 24 h after injection of 188Re-labeled liposome was observed 120 days after treatment with 188Re-labeled and DOX-loaded liposome (Figure 4A). This study was further validated by the same group of authors wherein they showed that both 188Re-labeled liposomes and 188Re-labeled and DOX-loaded liposomes had similar biodistribution profile (68). The promising results obtained in these studies demonstrate the potential of radiochemotherapeutics for cancer treatment. In another study, Zavaleta et al. utilized the avidin/99mTc-labeled biotin-liposome system to prolong the retention of liposomes in the peritoneal cavity and draining lymph nodes in an ovarian cancer xenograft model (69). Due to increased retention of liposomes, enhanced drug delivery to the ovarian cancer cells could be achieved which helped in increasing the therapeutic efficacy.

Figure 4.

SPECT image-guided tumor targeting using liposome based carrier. (A) MicroSPECT/CT imaging of mice bearing human colon cancer (C26) xenografts after intravenous injection of 188Re-labeled-liposome at 4 h and 24 h post-injection. No uptake in the original tumor inoculation site at 24 h after injection of 188Re-labeled liposome was observed 120 days after treatment with 188Re-labeled and DOX-loaded liposome. Adapted from reference (68) with permission. (B) SPECT/CT imaging of rats bearing human gliosarcoma (9L) xenografts after intravenous injection of 111In-labeled liposomes at 48 h post-injection. MR-HIFU-mediated hyperthermia of the tumor in combination with 111In-labeled liposomes (left) and a control experiment with 111In-labeled liposomes only (right). Adapted from reference (71) with permission.

In another study, Head et al. studied the effects of SPECT image-guided combination therapy using radiofrequency ablation and intravenously administered 99mTc labeled liposomal carrier containing DOX in mice bearing human head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma xenografts (70). In vivo SPECT/CT imaging showed increased uptake of 99mTc-labeled liposome containing DOX in the ablated tumors compared to the non-ablated ones. Therefore, the authors concluded that this approach can be used for increased delivery of chemotherapeutics for cancer treatment. Recently, de Smet et al. studied the biodistribution pattern of temperature sensitive liposomes (TSLs) for image-guided drug delivery (71). The TSLs release compartmentalized drugs at the melting phase transition temperature of the lipid bilayer (72). The encapsulated drug could be quickly released from the drug carrier into the tumor microvasculature by using TSLs in combination with local heating of the tumor (73). Consequently, the drug is available at a cytotoxic concentration at the surrounding tumor cells. The authors synthesized 111In labeled liposomes co-encapsulated with DOX and [Gd(HPDO3A)(H2O)] for drug delivery guided by SPECT/MR imaging. The micellar formulation was administered in mice bearing gliosarcoma (9L) tumors. For drug release, mild hyperthermia (T = 42 °C) was induced in the tumor using high intensity focused ultrasound under MR image-guidance (MR-HIFU). In vivo SPECT imaging and biodistribution studies showed 4.4 times higher liposomal uptake after 48 h in MR-HIFU-treated tumors in comparison with controls (Figure 4B), while DOX concentration was increased by a factor of 7.9. The MR-HIFU mediated drug delivery guided by SPECT imaging might play an important role in cancer therapeutics.

The synthesis of DTPA-derivatized liposomes radiolabeled with different radiometals such as 99mTc and 111In (for SPECT), 68Ga (for PET) and 177Lu (for therapy), was reported by Helbok et al (74). The conditions for radiolabeling were optimized and in vitro serum stability of the radiolabeled agents were determined to be high (>80%). In vivo SPECT or PET imaging and biodistribution in Lewis rats showed different uptake patterns on use of different radionuclides for labeling. Lower retention in blood (<3.3 %ID/g) and lower liver uptake (<2.7 %ID/g) for 99mTc- and 68Ga, compared to 111In-labeled liposomes (blood, <4 %ID/g; liver, <3.6 %ID/g) was observed, demonstrating the potential impact of radiometals to the liposome distributions. In another study, Rangger et al. reported tumor targeting and SPECT imaging using dual-peptide conjugated multifunctional liposomes (75). For this purpose, liposomes were conjugated with RGD peptide binding to integrin αvβ3 receptors and a substance P peptide binding to neurokinin-1 receptors. The peptide conjugated liposomes were radiolabeled with 111In and administered in U87MG-tumor bearing mice. However, only a moderate tumor uptake (~ 2 %ID/g) and no further advantages via a dual-targeting approach were observed from in vivo SPECT imaging and biodistribution studies, raising questions about the suitability of produced liposome for tumor targeting. Another peptide (tyrosine-3-octreotide) conjugated liposomes were also reported to generate low to moderate tumor uptake (< 2.5 %ID/g) in xenografted mice (76). Also, synthesis of lactoferrin-conjugated PEGylated liposomes loaded with radioisotope complex, 99mTc-labeled N,N-bis(2-mercaptoethyl)-N',N'-diethylethylenediamine (99mTc-BMEDA) for SPECT-IGDD to brain was reported by Huang et al. (77). In vivo SPECT imaging and biodistribution studies revealed that lactoferrin conjugated PEGylated liposome showed two-fold higher brain uptake than control PEGylated liposome. Such strategy might hold promise for treatment of several brain disorders.

Recently, there have been continuous interests in the development of multifunctional liposomes incorporating paramagnetic, fluorescent and PET/SPECT/CT contrast agents as well as chemotherapeutic drugs for multimodality imaging and drug delivery (78–80). Multifunctional drug carrying liposomal carriers are promising candidates for disease theranostics allowing non-invasive multimodality imaging of their in vivo behavior with the synergistic incorporation of the inherent advantages from each imaging modality. In another study, Kim et al. reported the synthesis of 111In-labeled liposomal carrier loaded with a high content of dexamethasone palmitate, a chemotherapeutic adjuvant that decreases interstitial fluid pressure in tumors (81). The radiolabeled formulation was administered intravenously in mice bearing human lung cancer (A549) xenografts. In vivo SPECT imaging showed significant uptake of 111In-labeled drug carrier in tumor. Though dominant liver uptake was seen, no liver toxicity was observed. The authors speculated that enzymatically-catalyzed esterolysis would result in the release of dexamethasone from the liposomes. However, targeted drug delivery and its bioresponsive release behavior of the drug carrier in tumor environment must be demonstrated in suitable animal models to demonstrate the real usability of this approach in cancer theranostics.

Drug delivery using microparticles

Over the last several years, controlled release drug delivery systems based on microparticles, that encapsulate drug and release it at controlled rates over relatively long periods of time are being developed to address several issues related with traditional methods of drug administration (82, 83). While a variety of such devices have been used for drug delivery and its controlled release, biodegradable polymer microspheres are one of the most common types used for such applications (84). Such microspheres can encapsulate a wide variety of drugs and can be easily administered through syringe needles. However, some microparticles used for drug delivery suffer from certain limitations such as difficulty in large-scale manufacturing, inactivation of drug during preparation of drug-loaded microparticles, and poor control of drug release kinetics (82, 83). Also, this strategy is generally suitable for locoregional delivery of drugs and therefore has limited utility.

Vente et al. reported the synthesis of 166Ho-poly(L-lactic acid) microspheres for radioembolization of the liver (85). The authors used a small scout dose of 166Ho-poly(L-lactic acid) microspheres to predict the biodistribution of the therapeutic dose of the radiolabeled microspheres in a porcine model. For this purpose, a scout dose (60 mg) and then a `treatment dose' (540 mg) of 166Ho-poly(L-lactic acid) microspheres were administered into the hepatic artery of pigs and SPECT images were acquired. SPECT images of each animal were compared and the results confirmed that the scout dose can accurately predict the biodistribution of a treatment dose. In another study, Hao et al. reported the synthesis of metronidazole (MTZ)-loaded porous Eudragit®RS (ERS) microparticles for the treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection (86). The authors selected MTZ as a model drug, which has been widely used as a critical component of combination therapies for Helicobacter pylori infection (87). SPECT imaging and biodistribution studies in rabbits demonstrated that 131I-labeled microparticles were retained in stomach for over 8 h. Also it was demonstrated that MTZ-loaded microparticles could eradicate Helicobacter pylori infection completely with lower dose and administration frequency compared to pure drug. In another study, Kim et al. reported a method for delivering local high-dose radiation therapy by using micron-size radiation sources embedded in temperature-sensitive hydrogel (88). 111In was incorporated as the radioactive source in the hydrogel. The authors tested the feasibility of hydrogel delivery to human breast tumors by testing its injectability within the tumor microenvironment under intratumoral pressure. The radiolabeled hydrogel was directly injected into the tumor of mice and no polymerization of hydrogel during injection and intratumoral pressure was observed. In vivo SPECT imaging and biodistribution studies showed that the tumor uptake was much higher when 111In-labeled hydrogel was injected than when an equivalent dose of 111In in saline was injected. This preliminary study suggests that delivery of radiation source using temperature sensitive – hydrogel to a local tumor holds promise and warrants further investigation.

In the recent times, there have been considerable efforts towards developing new aerosol formulations and delivery devices that can target drugs to the lung periphery (89). SPECT imaging combined with lung function measurements and computational modeling can be used to assess the effect of inhaled drug therapy within the airways and in the lung periphery (89, 90). Leclerc et al. reported a comparative study of the nasal deposition patterns of micron and submicron particles using SPECT/CT measurements (91). For this purpose, radiolabeled nebulizations (containing 99mTc-DTPA aerosol) were performed on a plastinated model of human nasal cast coupled with a respiratory pump. The nasal deposition patterns of micron and submicron sized particles were compared and it was found that particles of higher size (2.8 μm) were efficiently deposited in the central nasal cavity contrary to the submicron (230 nm and 550 nm) aerosol particles. Also, it was observed that addition of a 100 Hz acoustic airflow to the 2.8 μm aerosol significantly enhanced the deposition in maxillary sinuses which represent a high interest for sinusitis pathologies treatment.

Drug delivery using nanoparticles

In the recent times, nanotechnology has become a rapidly expanding area of research with huge prospective in many emerging areas. It is increasingly becoming possible to manipulate matter at the atomic, molecular, and supramolecular scale to create new materials (with dimensions from one to hundreds of nanometers) with remarkably innovative properties. In cancer medicine, nanotechnology holds great promise to revolutionize clinical diagnostics, drug delivery and targeted therapy (11, 92–94). This is because nanoparticles demonstrate intense and stable output, high payload drug delivery, specific and strong target binding using suitable ligands, tunable biodistribution profiles, and possibility for multimodality imaging. However, rapid clearance of the nanoparticles by the reticuloendothelial system, high liver and spleen uptake and toxicity issues are some of the major limitations towards utilization of nanoparticles for IGDD (95). The different nanoparticle based systems which can be radiolabeled with suitable γ-emitting radioisotopes for SPECT-IGDD are discussed in the following text.

Inorganic nanoparticles

Among the various inorganic nanoparticles reported to date, the metallic nanoparticles (gold nanoparticles) and oxide nanoparticles (silica and superparamagnetic iron oxide) are most widely used for biomedical applications due to their biocompatibility, small size, ease of characterization, and rich surface chemistry (96–100). Morales-Avila et al. reported the synthesis of 99mTc-labeled gold nanoparticles conjugated with cRGD for targeting of integrin αvβ3 (101). In vivo SPECT imaging and biodistribution studies in mice bearing glioma (C6) tumors showed ~ 8 %ID/g tumor uptake, 3 h after intraperitoneal administration of the radiolabeled agent. The same group of authors reported the synthesis of 99mTc-labeled gold nanoparticles conjugated with Lys3-Bombesin for in vivo gastrin releasing peptide-receptor imaging (102). The radiolabeled agent was intravenously administered in mice bearing prostate cancer xenografts and a tumor uptake of ~ 6 %ID/g was observed 1 h post-injection. The work was extended by the development of lyophilized kits for 99mTc labeling to gold nanoparticles conjugated with Lys3-bombesin, cRGD or thiol-mannose (103). The same group also reported the utilization of 99mTc-labeled gold nanoparticle for sentinel lymph node detection (103). In another study, Agarwal et al. reported the synthesis of gold nanorods conjugated with the tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α) antibody (104). The nanoconjugate was subsequently radiolabeled with 125I and used as a dual-modality agent (photoacoustic and SPECT imaging) for visualization of the distribution of gold nanorods in articular tissues of the rat tail joints.

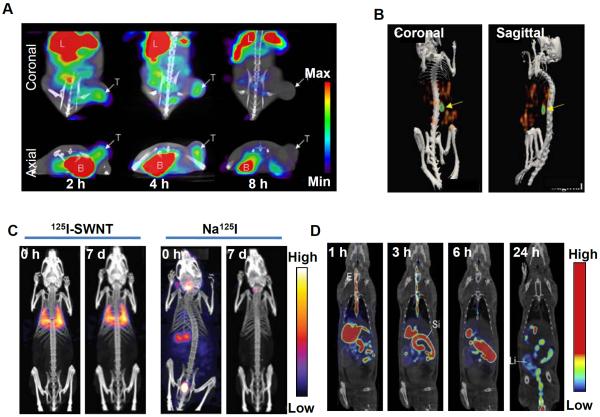

In an interesting study, You et al. reported the synthesis of multifunctional DOX-loaded hollow gold nanospheres targeting tyrosine kinase receptors overexpressed on the cell membrane of multiple tumors and angiogenic blood vessels (105). A peptide (TNYL-RAW) with high affinity towards tyrosine kinase receptors was conjugated with the nanospheres. The drug loaded nanoconjugate was radiolabeled with 111In and administered in EphB4-positive (Hey) tumor bearing mice. High tumor uptake of the radiolabeled nanoparticles was observed by SPECT imaging. Significantly decreased tumor growth was observed on therapy with DOX-loaded and TNYL-RAW conjugated gold nanospheres followed by NIR laser irradiation in comparison to treatments with non-targeted DOX-loaded nanospheres plus laser or gold nanospheres plus laser. The promising results obtained in this study demonstrate the potential of SPECT image-guided concerted photothermal-chemotherapy in cancer management. In another study, Kao et al. reported the synthesis of 123I-labeled gold nanoparticles conjugated with a monoclonal antibody, cetuximab, for targeting epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) expression in A549 human lung cancer (106). Significant tumor uptake could be observed by SPECT/CT imaging on administration of the radiolabeled agent intravenously in A549 tumor bearing mice (Figure 5A). In a similar study, Melancon et al. reported the synthesis of gold nanospheres conjugated with EGFR targeting aptamers or cetuximab (107). Cell binding assay showed selective binding of the nanoconjugate to EGFR. The nanoconjugate was radiolabeled with 111In and used for imaging EGFR expression in mice bearing oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSC-19) xenografts. Significant tumor uptake of the radiolabeled agent was observed by SPECT/CT imaging indicating the potential of this nanoplatform for selective thermal ablation of head and neck cancers overexpressing EGFR.

Figure 5.

SPECT image-guided tumor targeting using nanoparticle based carrier. (A) SPECT/CT imaging of mice bearing A549 tumor at 2, 4, and 8 h after intravenous injection of 123I labeled gold nanoparticles conjugated with cetuximab (B = Bladder, L = Liver, T = Tumor). Arrows indicate tumor. Adapted from reference (106) with permission. (B) SPECT/CT imaging of mice bearing SKOV-3 tumor, 24 h after intraperitoneal injection of 166Ho nanoparticles with surface-bound folate. Arrows indicate tumor. Adapted from reference (110) with permission. (C) Whole-body SPECT/CT images at different time points after intravenous injection (0 h and 7 days) of 125I-labeled single walled carbon nanotube (125I-SWNT) and free Na125I in normal Balb/c mice. Adapted from reference (124) with permission. (D) SPECT/CT images of rats after oral administration of 99mTc-labeled chitosan at 1, 3, 6 and 24 h. (E = esophagus; St = stomach; Li = large intestine). Adapted from reference (128) with permission.

Another metallic nanoplatform which has attracted considerable interest in nanomedicine is silver nanoparticles (108). The synthesis of poly(N-vinyl-2-pyrrolidone)-capped silver nanoparticles and their radiolabeling with 125I was reported by Chrastina et al (109). The suitability of the radiolabeled agent for in vivo SPECT imaging was demonstrated. In a different study, Di Pascua et al. reported the synthesis Ho nanoparticles which were irradiated in a nuclear reactor to produce 166Ho nanoparticles (110). In order to target ovarian SKOV-3 cancer cells overexpressing folate receptors, nanoparticles with surface-bound folate were prepared by adding DSPE-PEG5000-folate to the radioactive formulation. The radiolabeled formulation was administered intraperitoneally in mice bearing ovarian cancer xenograft and after 24 h, significant tumor accumulation (~ 15 %ID/g) of 166Ho was detected by SPECT/CT imaging (Figure 5B). However, no significant difference in tumor accumulation was observed (~ 13 %ID/g) when control 166Ho-nanoparticles without surface-bound folate were tested in the same animal model. Though the authors could not clarify the mechanism of tumor uptake of 166Ho-nanoparticle, such strategy might find utility in SPECT image-guided radiotherapy. The same group of authors further tested 166Ho containing mesoporous silica nanoparticle in the same animal model and similar results were obtained (111).

Iron oxide nanoparticles are gaining increasing popularity as nanoplatforms for multimodality molecular imaging (112, 113). Recently, Madru et al. reported the synthesis of 99mTc-labeled superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPIONs) for SPECT/MRI of sentinel lymph nodes (114). Sandiford et al. reported bisphosphonate-anchored PEGylation and 99mTc-labeling of SPION to achieve long blood circulation times (t½= 2.97 h) of the nanoparticles (115). The circulation half-life of free SPION is just few minutes. Another approach for surface engineering of SPION was reported by Lee et al (116). The authors used adenosine triphosphate (ATP) as a surface-coating material for functionalizing SPION (ATP@SPIONs). ATP@SPIONs were surface-modified with gluconic acid to diminish phagocytosis. The SPIONs were conjugated with cMet-binding peptide, radiolabeled with 125I and intravenously injected in mice bearing U87MG tumor and the tumors could be successfully visualized via multimodality SPECT/MR imaging. In a different approach, Park et al. reported the synthesis of core-shell (Fe3O4@SiO2) nanoparticles and conjugated 3-[131I]iodo-L-tyrosine on its surface for potential use in dual-modality SPECT/MR image-guided radiotherapy (117). Other hybrid core–shell nanosystems, bearing either magnetite (Fe3O4) or cobalt ferrite (CoFe2O4) have also been synthesized and radiolabeled with 99mTc for dual-modality PET/MR imaging (118).

Recently, a new nanoplatform (lipid-calcium phosphate nanoparticles) was synthesized and radiolabeled with 111In for SPECT/CT imaging of lymph node metastases (119). Owing to their favorable characteristics, such nanoparticles can also be used for lymphatic drug delivery. In another study, Kennel et al. reported the synthesis of 125mTe-labeled CdTe nanoparticles capped with ZnS (120). A monoclonal antibody (MAb 201B) that binds to murine thrombomodulin expressed in the lumen of lung blood vessels was attached to the nanoplatform and administered in normal mice. In vivo SPECT imaging and biodistribution studies revealed that the targeted (MAb 201B conjugated) nanoparticles accumulated in the lung (~ 400 %ID/g) within 1 h of intravenous injection while control antibody-coupled nanoparticles exhibited much lower accumulation in lung (~ 10 %ID/g). A large fraction of lung-targeted nanoparticles redistributed to spleen and liver or were excreted within few hours. This nanoplatform has the potential for SPECT image-guided drug delivery for treatment of lung diseases.

Carbon nanotubes

The unique physicochemical properties of carbon nanotubes with easy surface modification have led to a surge in exploring the potential of such materials as carriers for targeted delivery of chemotherapeutic drugs for cancer therapies (121, 122). A multi-walled carbon nanotube (MWNT)-based drug delivery system was developed by Wu et al (123). An antitumor agent 10-hydroxycamptothecin (HCPT) was covalently linked with the MWNT by a hydrophilic spacer of diaminotriethylene glycol through biocleavable ester linkage and a drug loading of ~16% of the MWNT-HCPT conjugates could be achieved. The MWNT-HCPT conjugate was radiolabeled with 99mTc and administered intravenously in hepatic (H-22) tumor bearing mice. In vivo SPECT imaging showed that radiolabeled MWNT-HCPT conjugate had a relatively long blood circulation and significant accumulation (~ 3.5 %ID/g) in the tumor site. The authors also demonstrated that MWNT-HCPT conjugates are superior in antitumor activity compared to clinical HCPT formulation, thereby justifying the use of carbon nanotubes for delivery of anti-cancer drugs. In another study, Hong et al. reported the synthesis of single-walled carbon nanotube (SWNT) filled with Na125I and covalently functionalized with biantennary carbohydrates, improving dispersibility and biocompatibility (124). The radiolabeled SWNT was injected in normal Balb/C mice. Predominant lung accumulation of 125I-labeled SWNT was detected with no signals in the thyroid, stomach or bladder (Figure 5C). When free 125I was administered, it mainly accumulated in thyroid, stomach or bladder (Figure 5C). These results suggest that there was no release of 125I from the SWNT in vivo following administration, thereby demonstrating suitability of such approaches for organ-specific therapeutics and diagnostics.

Polymeric nanoparticles

Polymeric nanoparticles are being increasingly used in IGDD because of their unique physicochemical properties, including biocompatibility and biodegradability (125). In addition, the functional groups of the polymer backbone allow surface modification to develop nanoparticles with diverse structures. The polysaccharide based nanoparticles such as chitosan and dextran are among the most widely investigated polymeric carriers for drug delivery (126, 127). Chen et al. reported the development of chitosan-based nanoparticle system for oral delivery of heparin, a potential anticoagulant (128). Since, heparin is poorly absorbed in the gastrointestinal track, either intravenous or frequent subcutaneous administration of heparin is required which cannot be done on an outpatient basis (129, 130). The drug loading efficiency was determined to be ~100%. The drug loaded chitosan nanoparticles were radiolabeled with 99mTc and administered orally in normal rats. Significant radioactivity uptake in the internal organs was not observed, indicating a minimal absorption of the nanoparticles into the systemic circulation (Figure 5D). Therefore, the authors concluded that chitosan nanoparticle can be used for oral delivery of drugs. In another study, Tian et al. reported the synthesis of glycyrrhetinic acid-modified chitosan/poly(ethylene glycol) nanoparticles for liver targeted drug delivery (131). In this system, glycyrrhetinic acid acted as the targeting ligand. The nanoparticles were labeled with 99mTc and intravenously administered in rats. High liver accumulation of radioactive nanoparticles was observed from SPECT imaging. Also, DOX was loaded in the nanoparticles and administered in mice bearing human liver cancer (H22) xenografts and it was found that the DOX-loaded chitosan nanoparticles could effectively inhibit tumor growth in H22 tumor bearing mice.

Recently, Polyak et al. reported the synthesis of folate-conjugated, biocompatible and biodegradable self-assembled chitosan nanoparticles radiolabeled with 99mTc for targeting tumor cells overexpressing folate receptors (132). In vitro studies confirmed that the nanoparticles accumulated in tumor (HeDe) cells overexpressing folate receptors. The radiolabeled nanoparticles were administered intravenously in tumor-transplanted rat models. In vivo SPECT/CT imaging showed considerably higher uptake in the tumorous kidney than in the non-tumorous contralateral organ and the difference existed for a long time. The uptake by the lungs and thyroid was negligible, confirming the stability of the radiolabeled nanoparticles in vivo. In another study, Chuang et al. reported the synthesis of poly(γ-glutamic acid)–ethylene glycol tetracetic acid conjugate (γPGA–EGTA) to form nanoparticles with chitosan for oral insulin delivery (133). The authors labeled insulin with 123I, loaded it in the nanoparticle system and administered orally in diabetic rats. In vivo SPECT imaging showed accumulation of 123I-labeled insulin in the heart, aorta, renal cortex, renal pelvis and liver, which is the normally expected biodistribution of insulin on oral delivery. The drug carrier played an important role in preventing enzymatic degradation of insulin, increasing its paracellular permeability and ensuring its sustained release to produce a significant and prolonged hypoglycemic effect in diabetic rats. These promising results demonstrate the potential of γPGA–EGTA for oral insulin delivery. Dextran is another member of the polysaccharide family which is used as a carrier for drug delivery (126, 134). Xie et al reported the efficacy of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) delivery using nanoparticles synthesized from glycidyl methacrylated dextran and gelatin for treatment of ischemic vascular diseases (135). Hind limb ischemia model was induced in rabbits and the ischemic limbs were treated with either empty nanoparticles or VEGF-containing nanoparticles. Hind limb blood perfusion was measured by SPECT imaging after 99mTc-sestamibi administration. Treatment with VEGF-containing nanoparticles significantly increased blood perfusion and vessel formation compared to treatment with empty nanoparticles, indicating the therapeutic role of this nanoplatform in angiogenesis.

Besides polysaccharide based nanoparticles, several other biodegradable polymeric nanoparticles have found utility in drug delivery applications (136). Lu et al. reported the synthesis of multifunctional hollow nanoparticles, self-assembling from poly(N-vinylimidazoleco-N-vinylpyrrolidone)-g-poly(D,L-lactide) graft copolymers and methoxyl/functionalized-PEG-PLA diblock copolymers for IGDD (137). An anticancer drug, DOX could be loaded in the hollow core of this multifunctional nanoparticle system and the flexible shell could be used for conjugation with folic acid and radiolabeling with 123I. Mice bearing human cervical cancer (HeLa) xenografts were treated with DOX-loaded radiolabeled nanoparticles. In vivo SPECT imaging showed high intratumoral accumulation (~6 %ID/g) of folic acid conjugated nanoparticles. The results of in vivo tumor growth inhibition studies indicated that nanoparticles demonstrated excellent antitumor activity and a high rate of apoptosis in cancer cells. The promising results obtained in this study demonstrate the potential of such polymeric nanoplatforms to accurately deliver drugs to targeted tumors for cancer therapy.

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

Though the field of IGDD is still in its infancy, it is progressing at an incredibly fast rate. It is a form of personalized therapy with the hybrid of imaging methods for guidance and monitoring of localized and targeted delivery of therapeutics to the disease lesions. The major goal in IGDD is to enhance the therapeutic ratio ideally through optimized biodistribution, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of drugs and personalization of therapeutic procedures. Successful implementation of IGDD requires integrated research efforts in multidisciplinary fields such as cell and molecular biology, material science, chemistry, engineering and physics and has opened up enormous prospects in pharmacokinetics, therapeutic target discovery, and drug delivery research.

Molecular imaging is the cornerstone for the success of IGDD procedures. Among various imaging modalities, nuclear imaging (SPECT or PET) play a key role in guiding the therapeutic events as they are fully translational and non-invasive functional imaging techniques with high sensitivity and provide information of the biological processes at molecular and metabolic levels in vivo (2, 18). SPECT is still the most widely used nuclear imaging modality in daily clinical routines all over the world (20, 31). This is primarily because of cost-effective availability of 99mTc (the most important SPECT radioisotope) from 99Mo/99mTc generators without dependence on onsite nuclear reactors or cyclotrons and wider availability of SPECT scanners. Also, the instrumentation for SPECT is relatively cheaper and is widely available all over the world. These favorable features make SPECT imaging more economical to use in clinical diagnosis, especially in developing countries. However, it cannot be denied that even the modern SPECT technology still suffers from comparatively low image quality. Therefore, SPECT imaging technology is now being improved to deal with this challenge (33). Further improvements in detector technology may fill the gap in spatial resolution when compared with PET. In fact, this process has already begun with development of small-animal SPECT scanners where the most recent major advances have been made to obtain SPECT images of improved quality (33). The combined use of SPECT with CT (hybrid SPECT/CT) is another game changer as it provides the momentum for a paradigm shift in use of SPECT into the quantitative domain in radionuclide emission tomography - a position occupied exclusively by PET until now. Nevertheless, in order to maintain the competitiveness of SPECT in the clinical arena, it is also essential to ensure the sustained production and cost-effective availability of different SPECT radioisotopes and especially the 99Mo/99mTc generator throughout the world (24, 138–144).

Numerous drug carriers based on natural and synthetic polymers, dendrimers, micelles, liposomes, microparticles, nanoparticles, etc. have developed which are able to deliver therapeutic drugs in a selective manner to improve the therapeutic outcome (145). Despite the availability of a plethora of research papers on development of new drug carriers, it is now widely believed that the nanoplatform based drug delivery approaches have greater potential for making advances which can be translated to clinics all over the world. This in turn would positively impact the overall diagnostic and therapeutic processes and thus enhance the quality of life for patients (13, 146, 147). A major advantage of nanotechnology is that it enables control over shape, size and multifunctionality of the drug delivery systems. Functionalization of the nanoparticles aids in appropriate surface modification of the drug carrier thereby minimizing their clearance by the immune system and prolonging circulation times to achieve better tumor targeting efficiency. Also, it is possible to attach suitable ligands (based on aptamers, peptides, proteins, antibodies, etc.) for targeting specific receptors to enhance tumor uptake of the drug carrier by receptor-mediated endocytosis in addition to EPR effect. Another important advantage of multifunctionality of the nanocarriers is that it offers the scope for multimodality molecular imaging which provides synergistic advantages over any single modality alone. In most cases, nanomaterial based drug carriers can protect the entrapped drugs from degradation during their delivery, thereby resulting in improved treatment effects. If required, several therapeutic agents can be simultaneously delivered by nanoplatforms to the disease site which might play a role in enhancing the therapeutic efficacy. Despite these excellent attributes, the design and fabrication of nanoparticles for theranostics still present many challenges which include biocompatibility, toxicity issues, pharmacokinetics, and cost-effectiveness (95). Also, many nanoparticles suffer from poor extravasation in tumor tissues (148–150). Therefore, vasculature-targeted delivery of imaging agents and therapeutic drugs is only possible using nanocarriers and their deep penetration into cancerous lesions has not yet been successfully achieved (95). The solution to these issues lies in nanoparticle design parameters such as shape, size, surface charge, composition, synthesis procedures, decoration with suitable molecules, and controlling drug loading and release kinetics. The recent innovations in materials science have led to the development of biodegradable, biocompatible, stimulus-responsive, and targeted drug delivery systems which have the potential to radically change the practice of IGDD (13).

While much of the SPECT-IGDD technology remains at a proof-of-principle stage, its potential for personalized disease management in humans is exceedingly attractive. Progress toward the clinical adaptation of this technology may be slow as of now, but can definitely be expedited with advancements in SPECT imaging procedures and innovations in fabrication of new drug delivery nanoplatforms which integrate programmability, targetability, and environmental responsiveness. It is worth mentioning that the silica based nanoplatforms have recently received the United States Food and Drug Administration (US FDA)-investigational new drug approval for a first-in-human clinical trial, due to their favorable characteristics, such as bulk renal clearance, acceptable targeting kinetics, lack of acute toxicity, and capability for multimodality imaging (151). Several other drug delivery nanoplatforms and nanosized anticancer drug products are also in the pipeline for achieving FDA approval for initiating clinical trials (152). We anticipate that these favorable developments will play in key role in fostering enthusiasm to develop new concepts in SPECT-IGDD with academia-industry-government partnership to facilitate “bench-to-bedside” translation of this novel approach, while satisfying the rigorous demands of the regulatory authorities in the near future.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is supported, in part, by the University of Wisconsin - Madison, the National Institutes of Health (NIBIB/NCI 1R01CA169365 and P30CA014520), the Department of Defense (W81XWH-11-1-0644), the American Cancer Society (125246-RSG-13-099-01-CCE), and the Fulbright Scholar Program (1831/FNPDR/2013).

References

- 1.Herschman HR. Molecular imaging: looking at problems, seeing solutions. Science. 2003;302(5645):605–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1090585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoffman JM, Gambhir SS. Molecular imaging: the vision and opportunity for radiology in the future. Radiology. 2007;244(1):39–47. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2441060773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weissleder R, Pittet MJ. Imaging in the era of molecular oncology. Nature. 2008;452(7187):580–9. doi: 10.1038/nature06917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kircher MF, Hricak H, Larson SM. Molecular imaging for personalized cancer care. Molecular Oncology. 2012;6(2):182–95. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weber WA, Grosu AL, Czernin J. Technology Insight: advances in molecular imaging and an appraisal of PET/CT scanning. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2008;5(3):160–70. doi: 10.1038/ncponc1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Z-Y, Wang Y-X, Lin Y, Zhang J-S, Yang F, Zhou Q-L, et al. Advance of Molecular Imaging Technology and Targeted Imaging Agent in Imaging and Therapy. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:12. doi: 10.1155/2014/819324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hatefi A, Minko T. Advances in image-guided drug delivery. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2012;2(1):1–2. doi: 10.1007/s13346-011-0057-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacKay JA, Li Z. Theranostic agents that co-deliver therapeutic and imaging agents? Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2010;62(11):1003–4. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chow EK, Ho D. Cancer nanomedicine: from drug delivery to imaging. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5(216):216rv4. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Terreno E, Uggeri F, Aime S. Image guided therapy: the advent of theranostic agents. J Control Release. 2012;161(2):328–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arias JL. Advanced methodologies to formulate nanotheragnostic agents for combined drug delivery and imaging. Expert Opin Drug Del. 2011;8(12):1589–608. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2012.634794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iyer AK, He J, Amiji MM. Image-guided nanosystems for targeted delivery in cancer therapy. Curr Med Chem. 2012;19(19):3230–40. doi: 10.2174/092986712800784685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Y, Chan HF, Leong KW. Advanced materials and processing for drug delivery: the past and the future. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2013;65(1):104–20. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fass L. Imaging and cancer: a review. Mol Oncol. 2008;2(2):115–52. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ametamey SM, Honer M, Schubiger PA. Molecular imaging with PET. Chem Rev. 2008;108(5):1501–16. doi: 10.1021/cr0782426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jennings LE, Long NJ. 'Two is better than one'--probes for dual-modality molecular imaging. Chem Commun (Camb) 2009;(24):3511–24. doi: 10.1039/b821903f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kiessling F, Fokong S, Bzyl J, Lederle W, Palmowski M, Lammers T. Recent advances in molecular, multimodal and theranostic ultrasound imaging. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2014;72C:15–27. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2013.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.James ML, Gambhir SS. A molecular imaging primer: modalities, imaging agents, and applications. Physiol Rev. 2012;92(2):897–965. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00049.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chakravarty R, Hong H, Cai W. Positron Emission Tomography Image-Guided Drug Delivery: Current Status and Future Perspectives. Mol Pharm. 2014 doi: 10.1021/mp500173s. DOI: 10.1021/mp500173s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mariani G, Bruselli L, Kuwert T, Kim EE, Flotats A, Israel O, et al. A review on the clinical uses of SPECT/CT. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37(10):1959–85. doi: 10.1007/s00259-010-1390-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bao S, Cao W, Li J. Advanced Topics in Science and Technology in China. Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2013. Radioisotope Labeled Molecular Imaging in SPECT. Molecular Imaging; pp. 313–32. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eckelman WC. Unparalleled contribution of technetium-99m to medicine over 5 decades. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2(3):364–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2008.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knapp FF, Jr., Mirzadeh S. The continuing important role of radionuclide generator systems for nuclear medicine. Eur J Nucl Med. 1994;21(10):1151–65. doi: 10.1007/BF00181073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]