Abstract

The cell surface receptor Fn14/TWEAKR was recently reported by our laboratory to be a prominent marker in the resistance exercise (RE) induced Transcriptome. The purpose of the present study was to extend our Transcriptome findings and investigate the gene and protein expression time course of markers in the TWEAK-Fn14 pathway following RE or run exercise (RUN). Vastus lateralis muscle biopsies were obtained from 6 RE subjects [25 ± 4 yr, 1-repetition maximum (RM): 99 ± 27 kg] pre- and 0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h post RE (3 × 10 at 70% 1-RM). Lateral gastrocnemius biopsies were obtained from 6 RUN subjects [25 ± 4 yr, maximum oxygen uptake (V̇o2max): 63 ± 8 ml·kg−1·min−1] pre- and 0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h after a 30-min RUN (75% V̇o2max). After RE, Fn14 gene and protein expression were induced (P < 0.05) and peaked at 8 and 12 h, respectively. Downstream markers analyzed showed evidence of TWEAK-Fn14 signaling through the alternative NF-κB pathway after RE. After RUN, Fn14 gene expression was induced (P < 0.05) to a much lesser extent and peaked at 24 h. Fn14 protein expression was only measurable on a sporadic basis, and there was weak evidence of alternative NF-κB pathway signaling after RUN. TWEAK gene and protein expression were not influenced by either exercise mode. These are the first human data to show a transient activation of the TWEAK-Fn14 axis in the recovery from exercise, and our data suggest the level of activation is exercise mode dependent. Furthermore, our collective data support a myogenic role for TWEAK-Fn14 through the alternative NF-κB pathway in human skeletal muscle.

Keywords: exercise, Fn14, skeletal muscle, TWEAK

recently, we completed a large microarray study in humans in which we identified a set (661) of genes that were responsive to resistance exercise (in the untrained and trained state) and correlated with whole muscle size and strength increases after a resistance training program (38). One of the most prominent genes in the array study, both with regards to fold change and correlation value, was fibroblast growth factor-inducible 14 (Fn14), which is also commonly known as the tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-like weak inducer of apoptosis (TWEAK)-receptor. The cell surface receptor Fn14 and its ligand TWEAK belong to the TNFα superfamily and their interaction has been known since 2001 (8, 56). Over the last decade, the TWEAK-Fn14 system has emerged as an important component of tissue remodeling in health and disease (9). Notably, cell and animal studies have also shown that the TWEAK-Fn14 system is a regulator of skeletal muscle biology and is involved in directing skeletal muscle atrophy, regeneration, and mitochondrial function (15, 40, 45).

TWEAK is expressed in many different tissues (31), including human skeletal muscle (38), but leukocytes constitute a major source of TWEAK and contribute to TWEAK's role in injury and inflammation (9). Fn14 is the smallest of all TNFα superfamily receptors and expressed at low levels by most healthy tissues (9), including skeletal muscle (21, 26, 38) and satellite cells (13, 19). Therefore, the activity of the TWEAK-Fn14 axis is greatly dependent on the induction of Fn14 expression (45). In animals, Fn14 has been shown to be highly inducible after cardiotoxin injury (19, 45) or denervation in skeletal muscle (40). Other relevant experimental models in which Fn14 is increased include mechanical stretch and hypertension-induced left ventricular hypertrophy in cardiac tissue of mice (10, 28, 29). Fn14 expression is also sensitive to growth factors such as the fibroblast growth factor (FGF) (which also gave rise to its name), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (8).

The TWEAK-Fn14 system signals via TNF receptor-associated factors (TRAFs) through the multifaceted nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) pathway (7, 9, 15, 52, 56). TWEAK-Fn14 is able to activate both the classical (i.e., canonical) and alternative (i.e., noncanonical) NF-κB pathway (14, 15, 45). High concentrations of TWEAK activate the classical NF-κB pathway, which impairs myogenesis through activation of myoblast proliferation and prevents cell cycle exit and further differentiation (11, 14). Prolonged elevated levels of TWEAK also appear to activate the classical NF-κB pathway and result in marked skeletal muscle atrophy in animals (12, 26, 40). Low concentrations of TWEAK have been shown to activate the alternative NF-κB pathway and elicit a promyogenic response by stimulating myoblast fusion (i.e., terminal differentiation) (14, 15). Collectively, the literature supports that a transient activation of the TWEAK-Fn14 axis is a physiological and promyogenic event, while prolonged or chronic axis activation (e.g., after substantial injury or during inflammation) is considered a pathological event which results in proteolysis and subsequent atrophy in skeletal muscle (15, 40, 45).

To date, relatively little is known about the TWEAK-Fn14 axis in human skeletal muscle. We were the first to report the induction of Fn14 after resistance exercise (RE), among young and old individuals (38). This Fn14 induction was targeted to fast-twitch muscle fibers (38), which hypertrophied with resistance training (37). We also reported that TWEAK gene expression was not affected by RE in young and old adults, which suggests that Fn14 induction is the main regulator of the TWEAK-Fn14 axis in human skeletal muscle (38). In support of our data, Merritt et al. (25) recently reported an increase in Fn14 gene expression and no change in TWEAK gene expression 24 h after an acute bout of RE in middle-aged and old individuals. Collectively, the human data to date suggest that the TWEAK-Fn14 axis has progrowth qualities in healthy human skeletal muscle.

The goal of the present study was to extend our Transcriptome findings (38) and further investigate the TWEAK-Fn14 axis following RE or RUN exercise in humans by examining the gene and protein expression time course of markers involved in the TWEAK-Fn14 pathway. The time course (pre- to 24-h postexercise) of the following 10 genes was investigated: TWEAK, Fn14, TRAF1, TRAF2, TRAF3, NIK (NF-κB inducible kinase), IKK2 (inhibitor of kappa-B kinase beta), IκBα (nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells inhibitor, alpha), PDGF, and VEGF. Protein expression was investigated in a subset of time points for the following proteins: TWEAK, Fn14, TRAF3, NIK, and NFKB2 (i.e., p100/p52). Considering the promyogenic qualities of Fn14, we hypothesized that RE (a hypertrophic stimulus) would elicit a greater induction of Fn14 and its downstream targets compared with RUN (an aerobic stimulus). We also hypothesized that TWEAK expression would not be induced at any time point after RE or RUN exercise.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Twelve healthy, nonsmoking, nonobese, and physically active volunteers participated in this research. Six subjects (2 F, 4 M) were included in the RE protocol, and six other subjects (1 F, 5 M) participated in the submaximal RUN protocol (Table 1). Subjects involved in the RE group had been performing resistance exercise ∼2 times/wk on a regular basis. Subjects involved in the RUN group had been running 3–5 times/wk consistently. All subjects were given oral and written information about the experimental procedures and potential risks before giving their written informed consent. All procedures conformed to the standards set forth by the Declaration of Helsinki, and these procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Ball State University.

Table 1.

Subject characteristics

| RE | RUN | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 25 ± 4 | 25 ± 4 |

| Weight, kg | 74 ± 14 | 72 ± 5 |

| Height, m | 1.71 ± 0.11 | 1.81 ± 0.07 |

| 1-RM, kg | 99 ± 27 | |

| % 1-RM lifted | 70 ± 1 | |

| V̇o2max, l/min | 4.5 ± 0.7 | |

| V̇o2max, ml·kg−1·min−1 | 63 ± 8 | |

| Avg trial % V̇o2max | 75 ± 4 |

Values are means ± SE. RE, resistance exercise; RUN, run exercise; 1-RM, concentric 1 repetition maximum of bilateral knee extension; V̇o2max, maximum O2 uptake.

Experimental Design

All subjects were familiarized with the procedures and equipment and had their anthropometric measures made prior to the trial. RE subjects were tested for their bilateral knee extensor concentric one repetition maximum (1-RM) on a Cybex Eagle Knee Extensor (Cybex, Medway, MA) ∼1 wk prior to the trial. On trial day, RE subjects performed 3 sets of 10 repetitions at 70% of their 1-RM with 2 min of rest between sets. The RUN subjects completed a V̇o2max test using an incremental treadmill test to voluntary exhaustion on a treadmill ∼10 days prior to the trial. Oxygen uptake was measured using indirect calorimetry as previously described (58). On trial day, RUN subjects performed 30 min of treadmill running at 75% of V̇o2max.

For both RE and RUN, subjects refrained from physical activity for at least 48 h prior to the preexercise muscle biopsy and rested in a supine position for at least 30 min prior to each muscle biopsy with the exception of the immediate postexercise time point. All trials began between 6 and 7 am. After the first, and through the 8-h postexercise muscle biopsies, subjects rested quietly in the laboratory. Thereafter, subjects were allowed normal ambulation and returned to the laboratory for the 12- and 24-h postexercise muscle biopsies. Subjects also fasted with ad libitum water intake at least 8 h prior to lying down for the preexercise muscle biopsy and through the 8-h postexercise muscle biopsy. Thereafter, they were fed standardized meals. The 24-h postexercise muscle biopsy was performed after an overnight fast of at least 8 h. It should be highlighted that this study builds upon our previously published time course papers (23, 58), which reported on the gene expression time course of myogenic, proteolytic, metabolic, and interleukin (IL)-related markers after RE and RUN in the same group of subjects as reported here. Therefore, the gene expression results in this manuscript are complementary to our previous genetic analyses of these same samples. The protein expression analysis conducted in the present study was guided by the novel gene expression findings.

Muscle Biopsies

Eight muscle biopsies (4) were taken from the vastus lateralis (VL) of RE subjects and from the lateral head gastrocnemius (LG) of RUN subjects; pre-, immediately post (0 h), and 1-, 2-, 4-, 8-, 12-, and 24-h postexercise. The muscle biopsies alternated between legs with each biopsy being more proximal than the one before on the same lower limb. Following each muscle biopsy, the muscle sample was divided up and placed in 0.5 ml of RNALater (Ambion, Austin, TX) and stored at −20°C until RNA extraction, or immediately frozen and stored in liquid nitrogen until Western blot analysis. The vastus lateralis and gastrocnemius are both considered to be muscles with mixed fiber types, and it was our intention to measure gene and protein expression in the muscles that are engaged in the specific mode of exercise and that have been commonly studied in exercise physiology research.

Muscle Homogenization and Protein Assay for Western Blot Analysis

Muscle samples (10–20 mg) were placed in 20 vol of RIPA buffer (Thermo Scientific) with freshly added Halt Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Thermo Scientific) and Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (Thermo Scientific), homogenized with a glass mortar and motorized glass pestle, and kept on ice. The resulting homogenate was clarified by a 1,000 g centrifugation for 5 min (4°C). The supernatant was collected and the protein concentration of each sample was determined with a BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific), using a bovine serum albumin standard. Specifically, after being stored on ice, a 10-μl aliquot from each sample was combined with 90 μl of RIPA buffer (plus inhibitors) (1:10 vol/vol), mixed thoroughly, and pipetted in triplicate (25 μl each) into a 96-well plate. Protein concentrations were read on an ELX808 IU microplate reader (BioTek). After successful protein assay was confirmed, the remaining sample volume was precisely measured and diluted (vol/vol) with 2X blue buffer [2% SDS, 12 mg/ml EDTA, 0.12 M tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane (pH 6.8), 2 mg/ml bromophenol blue, 15% glycerol and 10% β-mercaptoethanol].

Western Blot Analysis

Western blot analyses were performed as previously described by our laboratory (16, 53, 55). Each Western blot sample was heated in a heating block for 3 min at 95°C prior to its first Western blot use. Equal amounts of total protein, as determined by the BCA protein assay [20 μg for p100/p52, 40 μg for TWEAK, TRAF3 and NIK, and 60 μg for Fn14] were then separated with a 4–20% gradient gel with 10 wells (Thermo Scientific) using SDS-PAGE for 90 min at 100 V and transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (Immobilon-P, Millipore, Bedford, MA) for 90 min at 40 V at ∼4°C. The membrane was blocked with 5% milk in Tris-buffered saline (pH 7.6) and 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST) for 1 h (gently rocking at room temperature), washed (3 × 5 min) in 1xTBST, and incubated with a primary antibody in 1xTBST for TWEAK (1:2,000; ab86287, Abcam), Fn14 (1:2,000; ab109365, Abcam), TRAF3 (1:500; no. 4729, Cell Signaling), NIK (1:1,000; no. 4994, Cell Signaling), and NF-κB2 p100/p52 (1:500; no. 4882, Cell Signaling) at 4°C overnight. Blots were washed (3 × 5 min in 1xTBST), incubated in an anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:4,000; no. 7074, Cell Signaling) mixed with 5% milk in 1xTBST for 1 h, and washed again (4 × 15 min in 1xTBST) prior to being exposed for 5 min to enhanced chemiluminescent substrate (Amersham ECL Prime Western Blotting Detection Reagent, GE Healthcare). Excess chemiluminescent substrate was removed and the blot was placed inside a plastic sheet protector to allow digital images of protein bands to be captured using a chemiluminescent imaging system (FluorChem SP, Alpha Innotech). Protein band density was analyzed using the spot density analysis software provided with the imaging system.

On each gel, five muscle samples from an RE subject (pre, and 4, 8, 12, 24 h post) and four muscle samples from a RUN subject (pre, and 8, 12, 24 h post) were loaded (number of samples was guided by the gene expression results). Molecular weight markers See Blue Plus 2 (molecular mass range: 4–250 kDa) and MagicMark (molecular mass range: 20–220 kDa) (Invitrogen) were used throughout the study and loaded together in the 10th lane on all gels. The See Blue Plus 2 marker served as a visual guide during the gel run and transfer onto the PVDF membrane, while the MagicMark Western Protein Standard was relied upon during the imaging phase. The membranes were stained in a Ponceau solution (Sigma) to verify equal loading across samples (data not shown).

Total RNA Extraction and RNA Quality Check

Total RNA was extracted in TRI Reagent (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH). The quality and integrity (RIN of 7.6 ± 0.1) of extracted RNA (187.8 ± 8.7 ng/μl) was evaluated using an RNA 6000 Nano LabChip kit on an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA) as we have previously described (23, 24, 35, 58).

qPCR

Oligo(dT) primed first-strand cDNA was synthesized (120 ng of total RNA) using SuperScript II RT (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Quantification of mRNA levels (in duplicate) was performed in a 72-well Rotor-Gene 3000 Centrifugal Real-Time Cycler (Corbett Research, Mortlake, NSW, Australia). Housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as a reference gene, as we have previously described (20, 36). All primers used in this study were mRNA-specific (on different exons and crossing over an intron) and designed for qPCR (Vector NTI Advance 9 software, Invitrogen) using SYBR Green chemistry. Details about primer characteristics and sequences are presented in Table 2. The qPCR parameters have been described previously (23, 58). A melting curve analysis was generated for all qPCR runs to validate that only one product was present. A serial dilution curve (cDNA made from 500 ng of total RNA of human skeletal muscle; Ambion, Austin, TX) was generated for each qPCR run to evaluate reaction efficiencies. The amplification calculated by the Rotor-Gene software was specific and highly efficient (efficiency = 1.05 ± 0.01; R2 = 0.99 ± 0.00; slope = 3.21 ± 0.03). The expression of genes of interest was evaluated using the 2−ΔΔCt (fold change) relative quantification method (22, 23, 36).

Table 2.

Nomenclature, gene information, and mRNA characteristics

| Gene | Official Gene Symbol | Accession No. | Sequence (5′ → 3′) | Amplicon Size, bp | mRNA Region, bp | Annealing Temp, °C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TWEAK (tumor necrosis factor superfamily, member 12) | TNFSF12 | NM_003809.2 | F = GCCCATTATGAAGTTCATCCACGACC; R = GCAGAGGGCTGGAGCTGTTGATTCT | 109 | 421–529 | 60 |

| TWEAK-R or Fn14 (tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 12A) | TNFRSF12A | NM_016639.2 | F = ACTTCTGCCTGGGCTGCGCT; R = TCTCCTGCGGCATCGTCTCC | 137 | 271–407 | 60 |

| TRAF1 (TNF receptor-associated factor 1) | TRAF1 | NM_001190945.1a | F = GCCCAGGGCTCTCTGCTGTGC; R = GCCACCTCGGGGTGAGCCTTC | 150 | 521–670 | 60 |

| TRAF2 (TNF receptor-associated factor 2) | TRAF2 | NM_021138.3 | F = GAAAGAATACGAGAGCTGCCACGAAGG; R = TCCAGGTGGCGCTCCTTTTCA | 105 | 411–515 | 60 |

| TRAF3 (TNF receptor-associated factor 3) | TRAF3 | NM_145725.2b | F = GCCCTGCTGAGCTCTTCAAGTCCAAAA; R = CTCTGCACAACCTCTGCTTTCATTCC | 144 | 588–731 | 60 |

| NIK (NF-κB inducible kinase) | MAP3K14 | NM_003954.3 | F = CCCCAAGCTATTTCAATGGTGTGAAAG; R = AGCTGAAGGCTGCAGCTGGGATCT | 141 | 2670–2810 | 60 |

| IKK2 (inhibitor of kappaB kinase beta) | IKK2 | NM_001556.2a | F = ATGTCATCCGATGGCACAATCAGG; R = TGGGTCAGCCTTCTCATGATCTGG | 127 | 260–386 | 60 |

| IκBα (nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells inhibitor, alpha) | NFKBIA | NM_020529.2 | F = CCAACTACAATGGCCACACGTGTCTACA; R = GAGCATTGACATCAGCACCCAAGG | 99 | 646–744 | 60 |

| PDGF (platelet derived growth factor) | PDGFA | NM_002607.5c | F = CCATGTTCTGGCCGAGGAAGC; R = TCTCAGGCTGGTGTCCAAAGAATCC | 145 | 891–1035 | 60 |

| VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) | VEGFA | NM_001025366.2d | F = AGGAGTCCAACATCACCATGCAGATTA; R = TGCTCTATCTTTCTTTGGTCTGCATTCA | 119 | 1331–1449 | 60 |

The first sequence represents the forward (F) primer; the second sequence represents the reverse (R) primer.

Primers detect all 3 variants;

primers detect all 4 variants;

primers detect both variants;

primers detect all 9 variants.

Statistical Analysis

The gene and protein expression response to RE or RUN was examined using a one-way repeated-measures ANOVA. Significance was set at P < 0.05 (two-tailed). Main time effects (P < 0.05) were interpreted using the least significant difference (LSD) pairwise comparisons between preexercise and each postexercise time point (P < 0.05). We chose to perform the LSD pairwise comparisons as opposed to the Bonferroni correction since the LSD pairwise comparisons will provide the scientific community with valuable information about each gene's and protein's expression pattern in the 24-h recovery period after RE or RUN. We do not expect that other research teams will repeat our time course experiment, but instead they may select a specific time point based on the information provided by this investigation. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 17.0 for Windows software package. Data are presented as means ± SE.

RESULTS

The genes of interest in the present study were chosen as they represent markers in the TWEAK-Fn14 pathway, which primarily signals through the NF-κB system. The investigated genes capture targets in both the classical and alternative NF-κB pathways at eight time points (pre and 0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h post) in conjunction with RE or RUN. Protein analyses were guided by the gene expression data and thus examined at five time points (pre and 4, 12, and 24 h post) in the RE group and at four time points (pre and 8, 12, and 24 h post) in the RUN group. The gene expression data suggested activation of both the classical and alternative NF-κB pathway. However, mRNA of a well-established alternative pathway kinase, NIK, was greatly induced after exercise. Considering the lack of information on the alternative NF-κB pathway in human skeletal muscle, and recent reports of its involvement in myogenesis (14, 15), we chose to direct the protein analyses to representative markers of the alternative NF-κB pathway.

TWEAK-Fn14 Pathway Markers After RE

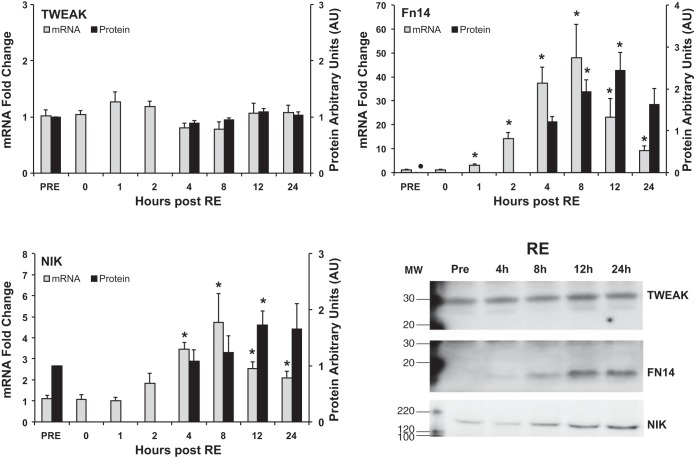

TWEAK and Fn14.

There was a large mRNA induction (P < 0.05) of the TWEAK receptor, Fn14, which started at 1 h (3.2-fold) and peaked at 8 h post (48.0-fold). Fn14 mRNA levels remained elevated through 24 h post RE (9.0-fold). Fn14 protein was nondetectable at pre, but became visible (Table 3) in all RE subjects at 4 h and increased (P < 0.05) further at 8 h and peaked 12 h post RE (Fig. 1). TWEAK gene and protein expression was unaffected in the span of 24 h after RE (Fig. 1).

Table 3.

Fn14 protein expression among RE and RUN subjects

| Subject | Pre | 4 h | 8 h | 12 h | 24 h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RE-1 | − | x | x | x | x |

| RE-2 | − | x | x | x | x |

| RE-3 | − | x | x | x | x |

| RE-4 | − | x | x | x | x |

| RE-5 | − | x | x | x | x |

| RE-6 | − | x | x | x | x |

| RUN-1 | − | n/a | x | x | |

| RUN-2 | − | n/a | |||

| RUN-3 | − | n/a | x | ||

| RUN-4 | − | n/a | x | ||

| RUN-5 | − | n/a | |||

| RUN-6 | − | n/a | x | x |

Preexercise Fn14 protein levels are not detectable (−) in 60 μg of total protein. Fn14 expression is detectable (x) starting at 4 h post RE, but after RUN (8 to 24 h post) the expression pattern is much more sporadic. n/a, not applicable.

Fig. 1.

Gene and protein expression time course of TWEAK, Fn14, and NIK after resistance exercise (RE). Gene expression (fold change) was measured at all 8 time points, while protein expression (arbitrary units, AU) was analyzed at 5 time points (Pre, and 4, 12, and 24 h post) in conjunction with RE. Western blot images are representative data for each protein of interest. MW, molecular weight marker (in kDa). *P < 0.05 compared with Pre. ●, Protein not detectable at this time point.

TRAF1, TRAF2, and TRAF3.

Immediately downstream of Fn14, there was little change in gene expression among the receptor-associated factors, TRAF1, TRAF2, and TRAF3, with only a slight elevation (P < 0.05) in TRAF2 mRNA levels at 12 and 24 h post RE (1.5 and 1.7-fold, respectively) (Table 4). Protein expression was measured for TRAF3 because of its purported involvement in the alternative NF-κB pathway (39, 43). There was a trend (P = 0.09) for TRAF3 induction (up 36%) at 24 h post RE (data not shown).

Table 4.

Gene expression fold change before (Pre), immediately post (0 h), and 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h post resistance exercise

| Gene | Pre | 0 h | 1 h | 2 h | 4 h | 8 h | 12 h | 24 h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRAF1 | 1.04 ± 0.12 | 1.06 ± 0.20 | 0.90 ± 0.13 | 1.11 ± 0.18 | 1.13 ± 0.23 | 1.27 ± 0.26 | 0.97 ± 0.13 | 1.40 ± 0.23 |

| TRAF2a | 1.04 ± 0.13 | 1.05 ± 0.11 | 0.91 ± 0.14 | 0.85 ± 0.09 | 0.99 ± 0.11 | 1.39 ± 0.20 | 1.50 ± 0.20* | 1.65 ± 0.17* |

| TRAF3 | 1.07 ± 0.17 | 1.47 ± 0.41 | 1.28 ± 0.33 | 1.32 ± 0.33 | 1.86 ± 0.47 | 3.08 ± 1.26 | 1.63 ± 0.37 | 1.59 ± 0.45 |

| IKK2a | 1.02 ± 0.10 | 1.09 ± 0.11 | 1.05 ± 0.07 | 1.17 ± 0.14 | 1.08 ± 0.02 | 0.98 ± 0.18 | 1.09 ± 0.11 | 1.69 ± 0.14* |

| IκBαa | 1.13 ± 0.25 | 1.17 ± 0.21 | 0.68 ± 0.09 | 0.50 ± 0.07* | 1.35 ± 0.41 | 0.75 ± 0.21 | 0.42 ± 0.04* | 0.98 ± 0.16 |

| PDGF | 1.08 ± 0.17 | 0.98 ± 0.23 | 0.87 ± 0.12 | 0.97 ± 0.18 | 1.99 ± 0.49 | 3.05 ± 1.06 | 2.05 ± 0.74 | 1.52 ± 0.49 |

| VEGFa | 1.08 ± 0.18 | 1.22 ± 0.29 | 3.01 ± 0.62* | 3.13 ± 0.66* | 2.84 ± 0.39* | 2.30 ± 0.58* | 1.98 ± 0.23* | 1.33 ± 0.28 |

Data are means ± SE. TRAF, TNF receptor-associated factor; IKK2, inhibitor of kappaB kinase beta; IκBα, nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells inhibitor, alpha; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Main time effect, P < 0.05;

P < 0.05 compared with Pre.

NIK.

Further downstream the NF-κB inducible kinase, NIK, is a well-established marker of the alternative NF-κB pathway (39, 44). NIK gene expression was elevated (P < 0.05) by 4 h (3.5-fold), peaked at 8 h (4.7-fold), and remained elevated through 24 h post RE (2.0-fold) (Fig. 1). In agreement with the gene data, NIK protein expression nearly doubled (P < 0.05) by 12 h and still appeared elevated at 24 h post (Fig. 1).

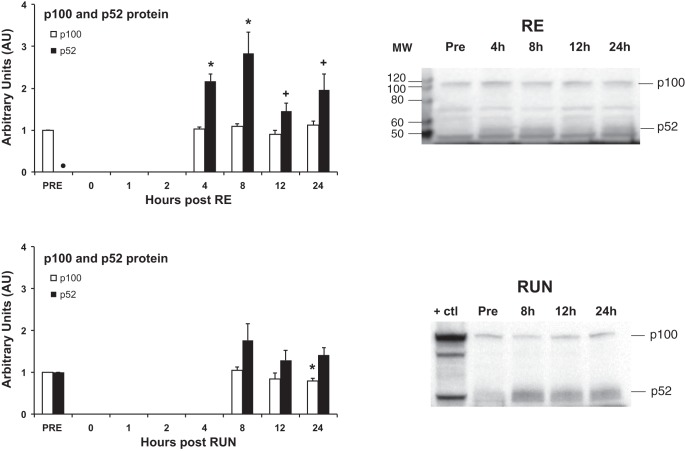

p100-p52.

The cleavage processing of p100 into p52 is considered a signature step of the alternative NF-κB pathway, and thus Western blot analysis illustrating this p100-p52 cleavage process has become a hallmark analysis for the alternative pathway (39). After RE, p52 protein levels were increased (P < 0.05) at 4 and 8 h, and tended to be increased (P < 0.07) at 12 and 24 h post, indicative of alternative NF-κB pathway activation (Fig. 2). There was no significant change detected in p100 protein levels.

Fig. 2.

p100 and p52 protein expression time course after resistance exercise (RE) or run exercise (RUN). Protein expression was analyzed at 5 time points (pre and 4, 12, and 24 h post) in conjunction with RE, and at 4 time points (Pre and 8, 12, and 24 h post) in conjunction with RUN. MW, molecular weight marker (in kDa); +ctl, positive control. *P < 0.05 compared with Pre. ●, Protein not detectable at this time point. +P < 0.07 compared with Pre.

IKK2 and IκBα.

IKK2 mRNA was only elevated (P < 0.05) at 24 h post (1.7-fold), while IκBα mRNA levels were decreased (P < 0.05) at 2 h (0.5-fold) and 12 h (0.4-fold) post RE (Table 4). Protein expression of classical NF-κB pathway markers was not evaluated.

VEGF and PDGF.

We also examined the mRNA levels of the two growth factors PDGF and VEGF since they have been shown to impact Fn14 expression in vitro (8). Only VEGF appeared responsive to RE, with an induction (P < 0.05) that peaked at 2 h (3.1-fold) and remained elevated through 12 h post (2.0-fold) (Table 4). VEGF and PDGF protein expression was not evaluated.

TWEAK-Fn14 Pathway Markers After RUN

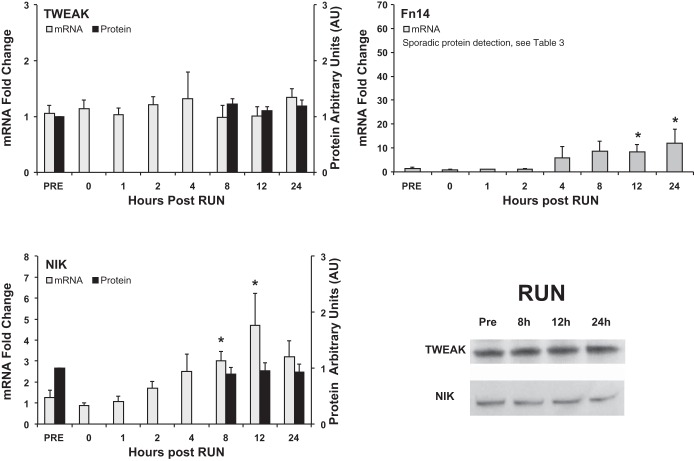

TWEAK and Fn14.

Fn14 mRNA levels were not induced until 12 h (8.5-fold) and peaked 24 h (12.0-fold) post RUN (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3). Although there was an increase in Fn14 gene expression, this was not enough to elicit a detectable increase in Fn14 protein levels. Contrary to the homogeneous Fn14 protein induction in the RE subjects, Fn14 protein induction was sporadic in the runners, with only two of six runners showing induction at 8 h, and two of six at 12 h and at 24 h post RUN (Table 3). Given the sporadic Fn14 protein expression no statistics were conducted on this data set. RUN had no significant impact on the TWEAK mRNA and protein levels in the 24-h period after exercise (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Gene and protein expression time course of TWEAK, Fn14, and NIK after run exercise (RUN). Gene expression (fold change) was measured at all 8 time points, while protein expression (arbitrary units, AU) was analyzed at 4 time points (Pre and 8-, 12-, and 24-h post) in conjunction with RUN. Western blot images are representative data for each protein of interest. *P < 0.05 compared with Pre.

TRAF1, TRAF2, and TRAF3.

Interestingly, TRAF1, TRAF2 (P = 0.08 time effect), and TRAF3 were all affected by RUN (Table 5). TRAF1 was induced (P < 0.05) at 1 h (1.9-fold), and at 8 to 24 h with a peak at 24 h post (2.7-fold). Similarly, TRAF2 was induced (P < 0.05) at 1 h (1.8-fold) and at 12 to 24 h with a peak at 12 h post (2.2-fold) RUN. Last, TRAF3 was also increased at 1, 2, and 8 to 24 h with a peak at 24 h post (3.9-fold) RUN (Table 5). Although there was a robust increase in TRAF3 mRNA after RUN, there was no change in TRAF3 protein levels 8–24 h after exercise (data not shown).

Table 5.

Gene expression fold change before (Pre), immediately post (0 h), and 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h post-run exercise

| Gene | Pre | 0 h | 1 h | 2 h | 4 h | 8 h | 12 h | 24 h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRAF1a | 1.12 ± 0.25 | 1.17 ± 0.11 | 1.87 ± 0.17* | 1.58 ± 0.15 | 1.89 ± 0.51 | 2.29 ± 0.43* | 2.22 ± 0.39* | 2.68 ± 0.35* |

| TRAF2b | 1.06 ± 0.16 | 1.38 ± 0.24 | 1.77 ± 0.42* | 1.83 ± 0.49 | 1.49 ± 0.23 | 1.71 ± 0.30 | 2.21 ± 0.51* | 2.04 ± 0.29* |

| TRAF3a | 1.12 ± 0.26 | 1.41 ± 0.16 | 1.90 ± 0.41* | 1.98 ± 0.51* | 2.59 ± 0.99 | 2.72 ± 0.65* | 3.60 ± 1.02* | 3.85 ± 0.71* |

| IKK2a | 1.08 ± 0.17 | 1.52 ± 0.18 | 1.74 ± 0.24 | 1.41 ± 0.10 | 1.48 ± 0.17 | 1.54 ± 0.18 | 1.89 ± 0.18* | 2.62 ± 0.62 |

| IκBαa | 1.03 ± 0.11 | 1.28 ± 0.15* | 1.15 ± 0.22 | 1.11 ± 0.22 | 0.82 ± 0.21 | 0.87 ± 0.16 | 0.62 ± 0.11* | 1.37 ± 0.31 |

| PDGF | 1.04 ± 0.13 | 0.80 ± 0.18 | 1.12 ± 0.11 | 1.65 ± 0.54 | 1.55 ± 0.36 | 2.30 ± 0.70 | 1.15 ± 0.14 | 2.13 ± 0.74 |

| VEGFa | 1.17 ± 0.30 | 1.28 ± 0.05 | 2.96 ± 0.78* | 3.40 ± 0.99* | 2.86 ± 0.67* | 2.64 ± 0.42* | 2.42 ± 0.37* | 1.85 ± 0.27* |

Data are means ± SE.

Main time effect, P < 0.05;

main time effect trend, P = 0.08;

P < 0.05 compared with Pre.

NIK.

NIK gene expression was elevated (P < 0.05) at 8 h (3.0-fold) and 12 h (4.7-fold), but no change was detected in NIK protein levels 8 to 24 h post RUN (Fig. 3).

p100-p52.

There was a small decrease in p100 protein expression at 24 h post RUN, but no significant change was detected in p52 protein levels at any time point (Fig. 2).

IKK2 and IκBα.

IKK2 gene expression was elevated (P < 0.05) at 12 h post (1.9-fold), while IκBα mRNA levels decreased (P < 0.05) at 12 h (0.6-fold) post RUN (Table 5). Protein expression of classical NF-κB pathway markers was not evaluated.

VEGF and PDGF.

VEGF mRNA levels were affected by RUN as evidenced by an increase (P < 0.05) that started immediately post, peaked at 2 h (3.4-fold), and remained elevated through 24 h post (1.9-fold) RUN (Table 5). PDGF was not affected by RUN exercise. VEGF and PDGF protein expression was not evaluated.

DISCUSSION

In recent years it has become increasingly clear that the TWEAK-Fn14 pathway is involved in the regulation of skeletal muscle mass in animals (15, 40). Simultaneously, our laboratory has compiled convincing evidence that the TWEAK-Fn14 axis is intricately involved in the skeletal muscle biology of humans. We recently reported that human skeletal muscle Fn14 gene expression is very responsive to resistance exercise, targeted to fast-twitch muscle fibers, and its induction positively correlates with skeletal muscle growth and functional improvements at the myocellular and whole muscle level (38). The objectives of the present study were to extend our previous findings and further investigate the cell surface receptor Fn14 and its ligand TWEAK's regulation following exercise in humans. We examined the mixed muscle gene and protein expression time course of markers in the TWEAK-Fn14 pathway after a typical RE bout (3 × 10 at 70% of 1-RM) or a 30-min RUN. Our new data show 1) the TWEAK-Fn14 axis is transiently activated in the recovery from exercise in human skeletal muscle, 2) Fn14 appears to be the primary regulator of the TWEAK-Fn14 axis after exercise, 3) RE substantially stimulates Fn14 expression, while RUN stimulation of Fn14 is more modest, and 4) RE activates the alternative NF-κB pathway.

From our perspective, Fn14’s consistent induction with exercise is intriguing. In the Transcriptome study, 28 of 28 subjects induced Fn14 gene expression after an acute RE bout (identical bout to present study) (38). Highly trained college runners exhibited a robust Fn14 gene response targeted to the fast-twitch fibers after tapered run training, during a time when these muscle fibers substantially increased in size (24, 27). We are now adding another 12 subjects to this “human pool,” verifying our previous microarray RE findings, and also showing that RE affects Fn14 gene and protein expression more so than RUN. The time course design revealed new information about Fn14’s induction pattern after RE and the magnitude of induction is noteworthy. The Fn14 protein data presented here are the first reported in human skeletal muscle. Considering we were only able to detect Fn14 protein on a consistent basis after RE, it appears that a robust gene expression response beyond resting levels may be required in order for the Fn14 protein levels to become detectable. Our time course data also suggest that the Fn14 induction is transient since Fn14 mRNA and protein levels were lower at 24 h post RE compared with 8 and 12 h post, which is indicative of a healthy response (8). The animal research to date has relied upon more extreme stimuli such as cardiotoxin injury or denervation, while we show that modest exercise bouts can activate the TWEAK-Fn14 axis in humans. Collectively, our laboratory's Fn14 data and those from Merritt et al. (25) strongly support that Fn14 is a desired component of the biology involved in the postexercise recovery.

TWEAK mRNA and protein levels were remarkably consistent throughout the 24-h time course after RE, and these data extend and support previous TWEAK mRNA findings after RE (25, 38). Collectively, the data suggest that human skeletal muscle contains a steady low amount of TWEAK and a regular bout of exercise is not insulting enough to elicit an increase in this cytokine. Interestingly, and in line with the hypertrophic nature of RE, it has recently been shown that low concentrations of TWEAK encourage myoblast fusion (14, 15). In animal skeletal muscle, TWEAK levels have been shown to increase dramatically after cardiotoxin injury (19, 45), in which an inflammatory response is elicited.

It is well established that the TWEAK-Fn14 system signals through the multifaceted NF-κB pathway (9, 15, 56), including the classical and alternative NF-κB pathways. The classical pathway can be activated by several cytokines (e.g., TNFα and IL-1), while activation of the alternative pathway is more selective (1, 39, 43), further complicating the interpretation. The two pathways differ greatly in the speed of signal transduction since the alternative pathway relies upon de novo synthesis of its well-known kinase, NIK, to further transduce the signal (39, 44). In the absence of a signal, NIK is constitutively degraded and does not stabilize/accumulate until there is a signal coming via a receptor such as Fn14. Once stable, NIK phosphorylates IKK1, which then phosphorylates p100, upon which p100 is cleaved into p52. Next, p52 combines with RelB to form a heterodimer and enters the nucleus as a transcription factor. The accumulation of NIK and p52 are considered hallmark steps in the activation of the alternative NF-κB pathway (39, 44). Considering our NIK mRNA findings, we chose to focus our protein analyses on the alternative NF-κB pathway. To our knowledge, these are the first protein data on NIK and p100/p52 in human skeletal muscle in conjunction with exercise. NIK protein levels were elevated by 72% at 12 h post RE, clearly showing an accumulation of this pivotal pathway protein. Further evidence for alternative pathway activation was generated through the increase we noted in p52 protein levels starting at 4 h post RE, an increase that lasted through the 24-h time point. We did not see a concomitant drop in p100, but it is possible that p100 levels were kept steady via increased mRNA levels and subsequent protein synthesis of p100.

In the present study we also measured the gene expression of the classical NF-κB pathway markers shown to be affected by TWEAK-Fn14 signaling in cells and animals, namely IKK2 and IκBα (11, 21). IKK2 was relatively unresponsive to exercise. Directly downstream of IKK2, IκBα gene expression decreased early post RE, which is likely a result of quick IκBα protein synthesis in response to its degradation (which occurs upon phosphorylation by IKK2) (3, 41). Upon phosphorylation by IKK2 and degradation, IκBα releases NF-κB, which allows NF-κB to move into the nucleus and initiate transcription of many different genes (32, 57).

Given the human model used here, we cannot say for certain if TWEAK-Fn14 activates both the classical and alternative NF-κB pathway after RE. The classical pathway in particular can be activated by many cytokines (30). It has also previously been shown that a more vigorous bout of RE (same intensity but 3 times greater volume compared with our RE bout) activates the classical NF-κB pathway (51). Our prior time course investigation in these resistance exercisers and runners also supports activation of the classical NF-κB pathway (23). In fact, the classical NF-κB pathway has been shown to impact Fn14 gene expression (57), so it is likely that activation of the classical pathway precedes activation of the alternative NF-κB pathway, which relies on Fn14 induction (14). Therefore, considering the quick signal transduction of the classical pathway, the Fn14 induction time course reported here, and the stable TWEAK levels, it is less likely that TWEAK-Fn14 signals through the classical NF-κB pathway after RE in humans. Collectively, our new gene and protein expression data suggest that the TWEAK-Fn14 axis is potentially involved in the activation of the alternative NF-κB pathway after RE. These data are novel since activation of this pathway has not been previously examined in human skeletal muscle. Importantly, these findings are in line with the recent data from Enwere et al. (14, 15), showing how TWEAK-Fn14 activates the alternative pathway and results in myotube fusion. Previous animal data also suggest that the alternative NF-κB pathway is involved in supporting the oxidative phenotype of skeletal muscle through mitochondrial biogenesis (2), which of course would be an advantage to exercising muscles.

We also analyzed mRNA levels of the TNF receptor-associated factors TRAF1, TRAF2, and TRAF3, all of which have been reported to associate with Fn14’s cytoplasmic tail and mediate the communication between Fn14 and the NF-κB pathways (7). TRAF3 protein levels were also examined because of its purported role in regulating the alternative pathway (via regulation of NIK) (39, 44). To our knowledge, these are the first TRAF data reported in conjunction with exercise in human skeletal muscle. Only TRAF2 gene expression was slightly increased after RE, and a trend for increased TRAF3 protein was noted post RE. Collectively, these data suggest that TRAF levels in RE-trained muscle are adequate to handle signal transduction upon Fn14 induction, and any other TNF-related cytokine signaling through these receptor-associated factors.

TWEAK-Fn14 Pathway Findings After RUN

The Fn14 mRNA induction was modest after RUN. In addition, we were only able to detect Fn14 protein on a sporadic basis after RUN (see Table 3), and therefore we did not conduct any statistics on these data. The different Fn14 mRNA and protein induction pattern between RE and RUN suggests that Fn14 induction is dependent on the exercise mode and thus type of muscle contraction. The RE bout consisted of 30 high intensity concentric-eccentric contractions (3 × 10 at 70% of 1-RM), and this protocol has resulted in skeletal muscle hypertrophy and strength gains if performed over a 12-wk period in our laboratory with different populations (37, 42, 47–49, 54). It is unlikely the robust Fn14 induction among our trained RE subjects was due to injury after the RE bout. We have previously shown that an identical bout of RE in resistance exercise-naive participants does not increase creatine kinase levels during the first 24 h after exercise (59). The 30-min aerobic RUN protocol used in this study resulted in ∼2,700 submaximal contractions (based on the 180 run strides/min estimate, 90 per leg). It should be noted that the subjects in this study were accustomed to RE or RUN, and therefore the exercise stimulus was not novel to them.

It is also possible that peak induction of Fn14 after RUN occurred beyond the 24-h time course investigated here. Fiber type differences between the VL in the lifters (MHC I, 33%; MHC II, 67%) and the LG in the runners (MHC I, 56%; MHC II, 44%) (58) should also be considered when interpreting the Fn14 data. The slightly greater amount of MHC II in the RE group may have impacted the fold-change seen in Fn14 mRNA after RE [since Fn14 induction is targeted to MHC II (27, 38)], but it is unlikely to have impacted the time-course difference seen between RE and RUN.

TWEAK mRNA and protein did not change after RUN, which combined with the RE data strongly suggest that TWEAK levels are not affected by regular exercise in humans. NIK mRNA levels increased post RUN, but interestingly we did not detect any differences in NIK protein levels. We also did not detect any convincing changes in p100 and p52, other than a slight drop in p100 at 24 h post RUN. Collectively, these data are more diffuse and are not convincing to support an activation of the alternative NF-κB pathway within the first 24 h after RUN.

While TRAF levels were barely induced after RE, TRAF1, TRAF2, and TRAF3 were all elevated early after RUN exercise. Since this TRAF induction preceded any Fn14 induction after RUN, this may suggest that other TNF family receptors, most of which associate with TRAFs (6), are activated by cytokines in response to RUN. In support of this notion, we previously reported a biphasic mRNA induction of cytokines TNFα, IL-6, and IL-8 after RUN (23), which is also indicative of classical NF-κB pathway activation given these are all target genes of NF-κB. The mRNA levels of these cytokines increased immediately post RUN after which they returned to basal levels before increasing again to peak levels at 8 to 24 h post RUN. These three cytokines are also known to be circulating in plasma after exhaustive running exercise (33). A further increase in TRAF1, -2, and -3 after RUN was also noted between 8 and 24 h post, which corresponds to the time frame when cytokine mRNA levels increased again (23). The IKK2 and IκBα data after RUN also support activation of the classical NF-κB pathway.

It should be noted that at the 24-h time point, the RUN-induced gene expression levels showed little signs of return toward basal levels in our present and our most recent time course investigation (23). A more prolonged activation of the classical NF-κB pathway is associated with proteolytic and inflammatory outcomes (30, 46), ultimately resulting in an anti-growth environment. This concept may partially explain the difference in skeletal muscle phenotype between resistance-trained and aerobically trained individuals.

We also investigated the gene expression time course of growth factors PDGF and VEGF, both known to induce Fn14 expression in vitro (8). VEGF mRNA levels were very responsive to both RE and RUN, which is in agreement with previous reports (17, 18, 34, 50), and the time course was very similar for both modes of exercise. PDGF induction did not reach statistical significance after either mode of exercise. Given the similar induction pattern of these growth factors after both RE and RUN, these markers likely played an insignificant role in Fn14 induction after exercise, which further supports that exercise mode and type of muscle contraction is more important for Fn14 induction.

Study Limitations

Given the multiple biopsies involved with this time course investigation, a crossover design was not realistic. This influenced our decision to select subjects accustomed to a particular exercise mode (RE vs. RUN), which should be taken into account when evaluating the time course data sets provided here. Moreover, the relatively small sample size with mixed sex may have limited our statistical power and data interpretation. Due to tissue limitations we did not investigate the phosphorylation state of any proteins in the NF-κB pathways that may have provided additional insight and warrants investigation in future studies. Last, we did not include a nonexercise control group to evaluate if numerous muscle biopsies (four per leg) influenced our results. However, Vella et al. (51) have recently shown that three muscle biopsies from the same leg did not affect the classical NF-κB pathway, suggesting that our multiple biopsies scheme did not influence our data set.

Summary

The present investigation presents novel information about TWEAK-Fn14 regulation after RE and RUN exercise in skeletal muscle of young adults. RE and RUN exercise induces a transient activation of the TWEAK-Fn14 axis, suggestive of a normal and physiologically coordinated response to exercise, although the magnitude and time course of activation appears to be exercise mode dependent. Our data also suggest that Fn14 is the regulatory step of TWEAK-Fn14 pathway activity after exercise. We show for the first time in human skeletal muscle that the alternative NF-κB pathway is activated after RE, and this activation may be through the TWEAK-Fn14 axis. Collectively, these new findings coupled with our recent Transcriptome data (38) promote a growth-related role for Fn14 in human skeletal muscle, which supports other reports of Fn14 being involved in myogenesis in cells and animals (13–15, 19).

GRANTS

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant AG-038576 (S. Trappe).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: U.R., B.J., Y.Y., and S.T. conception and design of research; U.R., B.J., Y.Y., and S.T. performed experiments; U.R., B.J., and S.T. analyzed data; U.R., B.J., Y.Y., and S.T. interpreted results of experiments; U.R. prepared figures; U.R. drafted manuscript; U.R., B.J., Y.Y., and S.T. edited and revised manuscript; U.R., B.J., Y.Y., and S.T. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bakkar N, Guttridge DC. NF-kappaB signaling: a tale of two pathways in skeletal myogenesis. Physiol Rev 90: 495–511, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bakkar N, Ladner K, Canan BD, Liyanarachchi S, Bal NC, Pant M, Periasamy M, Li Q, Janssen PM, Guttridge DC. IKKalpha and alternative NF-kappaB regulate PGC-1beta to promote oxidative muscle metabolism. J Cell Biol 196: 497–511, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beg AA, Finco TS, Nantermet PV, Baldwin AS Jr. Tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-1 lead to phosphorylation and loss of I kappa B alpha: a mechanism for NF-kappa B activation. Mol Cell Biol 13: 3301–3310, 1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergström J. Muscle electrolytes in man. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 68: 1–110, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradley JR, Pober JS. Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factors (TRAFs). Oncogene 20: 6482–6491, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown SA, Richards CM, Hanscom HN, Feng SL, Winkles JA. The Fn14 cytoplasmic tail binds tumour-necrosis-factor-receptor-associated factors 1, 2, 3 and 5 and mediates nuclear factor-kappaB activation. Biochem J 371: 395–403, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burkly LC, Dohi T. The TWEAK/Fn14 pathway in tissue remodeling: for better or for worse. Adv Exp Med Biol 691: 305–322, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burkly LC, Michaelson JS, Zheng TS. TWEAK/Fn14 pathway: an immunological switch for shaping tissue responses. Immunol Rev 244: 99–114, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chorianopoulos E, Heger T, Lutz M, Frank D, Bea F, Katus HA, Frey N. FGF-inducible 14-kDa protein (Fn14) is regulated via the RhoA/ROCK kinase pathway in cardiomyocytes and mediates nuclear factor-kappaB activation by TWEAK. Basic Res Cardiol 105: 301–313, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dogra C, Changotra H, Mohan S, Kumar A. Tumor necrosis factor-like weak inducer of apoptosis inhibits skeletal myogenesis through sustained activation of nuclear factor-kappaB and degradation of MyoD protein. J Biol Chem 281: 10327–10336, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dogra C, Changotra H, Wedhas N, Qin X, Wergedal JE, Kumar A. TNF-related weak inducer of apoptosis (TWEAK) is a potent skeletal muscle-wasting cytokine. FASEB J 21: 1857–1869, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dogra C, Hall SL, Wedhas N, Linkhart TA, Kumar A. Fibroblast growth factor inducible 14 (Fn14) is required for the expression of myogenic regulatory factors and differentiation of myoblasts into myotubes. Evidence for TWEAK-independent functions of Fn14 during myogenesis. J Biol Chem 282: 15000–15010, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Enwere EK, Holbrook J, Lejmi-Mrad R, Vineham J, Timusk K, Sivaraj B, Isaac M, Uehling D, Al-awar R, LaCasse E, Korneluk RG. TWEAK and cIAP1 regulate myoblast fusion through the noncanonical NF-kappaB signaling pathway. Sci Signal 5: ra75, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Enwere EK, Lacasse EC, Adam NJ, Korneluk RG. Role of the TWEAK-Fn14-cIAP1-NF-kappaB signaling axis in the regulation of myogenesis and muscle homeostasis. Front Immunol 5: 34, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galpin AJ, Raue U, Jemiolo B, Trappe TA, Harber MP, Minchev K, Trappe S. Human skeletal muscle fiber type specific protein content. Anal Biochem 425: 175–182, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gavin TP, Drew JL, Kubik CJ, Pofahl WE, Hickner RC. Acute resistance exercise increases skeletal muscle angiogenic growth factor expression. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 191: 139–146, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gavin TP, Robinson CB, Yeager RC, England JA, Nifong LW, Hickner RC. Angiogenic growth factor response to acute systemic exercise in human skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol 96: 19–24, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Girgenrath M, Weng S, Kostek CA, Browning B, Wang M, Brown SA, Winkles JA, Michaelson JS, Allaire N, Schneider P, Scott ML, Hsu YM, Yagita H, Flavell RA, Miller JB, Burkly LC, Zheng TS. TWEAK, via its receptor Fn14, is a novel regulator of mesenchymal progenitor cells and skeletal muscle regeneration. EMBO J 25: 5826–5839, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jemiolo B, Trappe S. Single muscle fiber gene expression in human skeletal muscle: validation of internal control with exercise. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 320: 1043–1050, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li H, Mittal A, Paul PK, Kumar M, Srivastava DS, Tyagi SC, Kumar A. Tumor necrosis factor-related weak inducer of apoptosis augments matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) production in skeletal muscle through the activation of nuclear factor-kappaB-inducing kinase and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase: a potential role of MMP-9 in myopathy. J Biol Chem 284: 4439–4450, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2[−Delta Delta C(T)] Method. Methods 25: 402–408, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Louis E, Raue U, Yang Y, Jemiolo B, Trappe S. Time course of proteolytic, cytokine, and myostatin gene expression after acute exercise in human skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol 103: 1744–1751, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luden N, Hayes E, Galpin AJ, Minchev K, Jemiolo B, Raue U, Trappe TA, Harber MP, Bowers T, Trappe SW. Myocellular basis for tapering in competitive distance runners. J Appl Physiol 108: 1501–1509, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Merritt EK, Stec MJ, Thalacker-Mercer A, Windham ST, Cross JM, Shelley DP, Craig Tuggle S, Kosek DJ, Kim JS, Bamman MM. Heightened muscle inflammation susceptibility may impair regenerative capacity in aging humans. J Appl Physiol 115: 937–948, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mittal A, Bhatnagar S, Kumar A, Lach-Trifilieff E, Wauters S, Li H, Makonchuk DY, Glass DJ. The TWEAK-Fn14 system is a critical regulator of denervation-induced skeletal muscle atrophy in mice. J Cell Biol 188: 833–849, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murach K, Raue U, Wilkerson B, Minchev K, Jemiolo B, Bagley J, Luden N, Trappe S. Single muscle fiber gene expression with run taper. PLoS One 9: e108547, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mustonen E, Sakkinen H, Tokola H, Isopoussu E, Aro J, Leskinen H, Ruskoaho H, Rysa J. Tumour necrosis factor-like weak inducer of apoptosis (TWEAK) and its receptor Fn14 during cardiac remodelling in rats. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 199: 11–22, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Novoyatleva T, Janssen W, Wietelmann A, Schermuly RT, Engel FB. TWEAK/Fn14 axis is a positive regulator of cardiac hypertrophy. Cytokine 64: 43–45, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oeckinghaus A, Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Crosstalk in NF-kappaB signaling pathways. Nat Immunol 12: 695–708, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ortiz A, Sanz AB, Munoz Garcia B, Moreno JA, Sanchez Nino MD, Martin-Ventura JL, Egido J, Blanco-Colio LM. Considering TWEAK as a target for therapy in renal and vascular injury. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 20: 251–258, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pahl HL. Activators and target genes of Rel/NF-kappaB transcription factors. Oncogene 18: 6853–6866, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pedersen BK, Hoffman-Goetz L. Exercise and the immune system: regulation, integration, and adaptation. Physiol Rev 80: 1055–1081, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prior BM, Yang HT, Terjung RL. What makes vessels grow with exercise training? J Appl Physiol 97: 1119–1128, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raue U, Slivka D, Jemiolo B, Hollon C, Trappe S. Myogenic gene expression at rest and after a bout of resistance exercise in young (18–30 yr) and old (80–89 yr) women. J Appl Physiol 101: 53–59, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raue U, Slivka D, Jemiolo B, Hollon C, Trappe S. Proteolytic gene expression differs at rest and after resistance exercise between young and old women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 62: 1407–1412, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raue U, Slivka D, Minchev K, Trappe S. Improvements in whole muscle and myocellular function are limited with high-intensity resistance training in octogenarian women. J Appl Physiol 106: 1611–1617, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raue U, Trappe TA, Estrem ST, Qian HR, Helvering LM, Smith RC, Trappe S. Transcriptome signature of resistance exercise adaptations: mixed muscle and fiber type specific profiles in young and old adults. J Appl Physiol 112: 1625–1636, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Razani B, Reichardt AD, Cheng G. Non-canonical NF-kappaB signaling activation and regulation: principles and perspectives. Immunol Rev 244: 44–54, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sato S, Ogura Y, Kumar A. TWEAK/Fn14 signaling axis mediates skeletal muscle atrophy and metabolic dysfunction. Front Immunol 5: 18, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schmid JA, Birbach A. IkappaB kinase beta (IKKbeta/IKK2/IKBKB)—a key molecule in signaling to the transcription factor NF-kappaB. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 19: 157–165, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Slivka D, Raue U, Hollon C, Minchev K, Trappe S. Single muscle fiber adaptations to resistance training in old (>80 yr) men: evidence for limited skeletal muscle plasticity. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 295: R273–R280, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sun SC. Non-canonical NF-kappaB signaling pathway. Cell Res 21: 71–85, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sun SC. The noncanonical NF-kappaB pathway. Immunol Rev 246: 125–140, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tajrishi MM, Zheng TS, Burkly LC, Kumar A. The TWEAK-Fn14 pathway: a potent regulator of skeletal muscle biology in health and disease. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 25: 215–225, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tak PP, Firestein GS. NF-kappaB: a key role in inflammatory diseases. J Clin Invest 107: 7–11, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Trappe S, Godard M, Gallagher P, Carroll C, Rowden G, Porter D. Resistance training improves single muscle fiber contractile function in older women. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 281: C398–C406, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Trappe S, Williamson D, Godard M. Maintenance of whole muscle strength and size following resistance training in older men. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 57: B138–B143, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Trappe S, Williamson D, Godard M, Porter D, Rowden G, Costill D. Effect of resistance training on single muscle fiber contractile function in older men. J Appl Physiol 89: 143–152, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Trenerry MK, Carey KA, Ward AC, Cameron-Smith D. STAT3 signaling is activated in human skeletal muscle following acute resistance exercise. J Appl Physiol 102: 1483–1489, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vella L, Caldow MK, Larsen AE, Tassoni D, Della Gatta PA, Gran P, Russell AP, Cameron-Smith D. Resistance exercise increases NF-kappaB activity in human skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 302: R667–R673, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vince JE, Chau D, Callus B, Wong WW, Hawkins CJ, Schneider P, McKinlay M, Benetatos CA, Condon SM, Chunduru SK, Yeoh G, Brink R, Vaux DL, Silke J. TWEAK-FN14 signaling induces lysosomal degradation of a cIAP1-TRAF2 complex to sensitize tumor cells to TNFalpha. J Cell Biol 182: 171–184, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Williamson D, Gallagher P, Harber M, Hollon C, Trappe S. Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway activation: effects of age and acute exercise on human skeletal muscle. J Physiol 547: 977–987, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Williamson DL, Gallagher PM, Carroll CC, Raue U, Trappe SW. Reduction in hybrid single muscle fiber proportions with resistance training in humans. J Appl Physiol 91: 1955–1961, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Williamson DL, Raue U, Slivka DR, Trappe S. Resistance exercise, skeletal muscle FOXO3A, and 85-year-old women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 65: 335–343, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Winkles JA. The TWEAK-Fn14 cytokine-receptor axis: discovery, biology and therapeutic targeting. Nat Rev Drug Discov 7: 411–425, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wu CL, Kandarian SC, Jackman RW. Identification of genes that elicit disuse muscle atrophy via the transcription factors p50 and Bcl-3. PLoS One 6: e16171, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang Y, Creer A, Jemiolo B, Trappe S. Time course of myogenic and metabolic gene expression in response to acute exercise in human skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol 98: 1745–1752, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang Y, Jemiolo B, Trappe S. Proteolytic mRNA expression in response to acute resistance exercise in human single skeletal muscle fibers. J Appl Physiol 101: 1442–1450, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]