Abstract

Increased vascular endothelial permeability and inflammation are major pathological mechanisms of pulmonary edema and its life-threatening complication, the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). We have previously described potent protective effects of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) against thrombin-induced hyperpermeability and identified the Rac pathway as a key mechanism of HGF-mediated endothelial barrier protection. However, anti-inflammatory effects of HGF are less understood. This study examined effects of HGF on the pulmonary endothelial cell (EC) inflammatory activation and barrier dysfunction caused by the gram-negative bacterial pathogen lipopolysaccharide (LPS). We tested involvement of the novel Rac-specific guanine nucleotide exchange factor Asef in the HGF anti-inflammatory effects. HGF protected the pulmonary EC monolayer against LPS-induced hyperpermeability, disruption of monolayer integrity, activation of NF-kB signaling, expression of adhesion molecules intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, and production of IL-8. These effects were critically dependent on Asef. Small-interfering RNA-induced downregulation of Asef attenuated HGF protective effects against LPS-induced EC barrier failure. Protective effects of HGF against LPS-induced lung inflammation and vascular leak were also diminished in Asef knockout mice. Taken together, these results demonstrate potent anti-inflammatory effects by HGF and delineate a key role of Asef in the mediation of the HGF barrier protective and anti-inflammatory effects. Modulation of Asef activity may have important implications in therapeutic strategies aimed at the treatment of sepsis and acute lung injury/ARDS-induced gram-negative bacterial pathogens.

Keywords: hepatocyte growth factor, guanine nucleotide exchange factors, cytoskeleton, pulmonary endothelium, inflammation, permeability, vascular leak

acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is often associated with sepsis and remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality with an overall mortality rate of 30–40% (26, 33). Increased capillary endothelial permeability and reduced alveolar liquid clearance capacity are major pathological mechanisms of pulmonary edema and ARDS. Mechanisms of endothelial cell (EC) permeability involve dynamic cytoskeletal changes, assembly and disassembly of cell-cell junctions, and signaling cross talk between various cytoskeletal compartments, such as actin networks and microtubules (24, 27). Interestingly, alterations in cell cytoskeleton also play an important role in the modulation of inflammatory responses. In vascular endothelium, inflammatory mediators increase expression of cell adhesion molecules [intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM), and E-selectin], which trigger adhesion and tissue transmigration of activated neutrophils (13, 40, 45). These events escalate general lung inflammation. However, little is known about intracellular processes, which determine lung EC barrier preservation and reduce inflammation in acute lung injury (ALI), and effective barrier-protective substances for ALI/ARDS treatment remain to be identified.

Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) is a prosurvival mediator that regulates different biological processes, including the maintenance of vascular barrier integrity, and appears at increased concentrations in lung circulation under pathological conditions such as ALI, sepsis, lung inflammation, and ventilator-induced lung injury (25, 34, 51). Novel therapeutic strategies using HGF have been suggested for cardiovascular diseases (1, 43). Increased HGF levels have been detected in inflamed lungs and are suggested to serve as a compensatory mechanism to help protect lung vascular integrity in ALI conditions and attenuate devastating consequences of lung inflammation and tissue injury (46). HGF binding to c-Met receptor stimulates receptor tyrosine kinase activity and recruitment of multiple SH2 domain-containing signaling molecules (32, 36). In turn, HGF-induced activation of Rac-GTPase leads to endothelial barrier protection via enhancement of the peripheral actin cytoskeleton and increased interactions between adherens junction proteins α/β-catenin and VE-cadherin (3, 23).

Our previous studies demonstrated the involvement of the Dbl family member Rac-specific guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) Tiam1 in the EC barrier protection induced by several agonists, including HGF (3, 10, 11, 37). However, Tiam1 downregulation did not cause complete suppression of HGF protective effects, suggesting activation of additional mechanisms. Another Rac/Cdc42-specific GEF, APC-stimulated guanine nucleotide exchange factor (Asef), has been originally identified in cancer cells. Asef contains Dbl homology domain exhibiting GEF activity, plekstrin homology domain which determines the subcellular localization and activity by interacting with phosphatidylinositol phosphate, Src homology (SH) 3 autoinhibitory domain, and a region that binds tumor suppressor adenomatous polyposis coli protein (APC) (19). Asef-dependent Rac and Cdc42 signaling has been implicated in regulation of actin cytoskeleton dynamics in epithelial and neuronal cells (20).

This study investigated the role of Asef in control of lung endothelial barrier. With the use of comprehensive evaluation of lung barrier function, including biochemical assays, imaging studies, molecular inhibition approaches, and a genetic animal model, this study investigated the role of Asef in HGF-mediated vascular barrier protection against lung inflammation and injury induced by bacterial pathogens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and reagents.

Human pulmonary artery endothelial cells (HPAEC) were obtained from Lonza (Allendale, NJ), propagated according to the manufacturer's recommendations, and used for experiments at passages five to seven. Human HGF was obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Cell-permeable c-Met kinase inhibitor, N-[3-fluoro-4-(7-methoxy-4-quinolinyl)phenyl]-1-(2-hydroxy-2-methylpropyl)-5-methyl-3-oxo-phenyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-pyrazole carboxamide, also known as carboxamide, was purchased from EMD Millipore (Billerica, MA). Carboxamide is a cell-permeable quinoline compound that acts as a potent inhibitor of HGF receptor c-Met (IC50 = 4 nM) and used as selective c-Met inhibitor in endothelial cells. Reagents for immunofluorescence were purchased form Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). Antibodies against NF-κB and IκBα were obtained from Cell Signaling (Beverly, MA); Asef, VE-cadherin, ICAM-1, and VCAM-1 antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Unless specified, biochemical reagents including LPS were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

Measurement of endothelial permeability.

The cellular barrier properties were analyzed by measurements of transendothelial electrical resistance across confluent human pulmonary artery endothelial monolayers using an electrical cell-substrate impedance sensing system (Applied Biophysics, Troy, NY) as previously described (2, 4). Express micromolecule permeability testing assay (XPerT) was recently developed in our group (14) and currently available from Millipore (catalog no. 17–10398; Vascular Permeability Imaging Assay). This assay is based on high-affinity binding of avidin-conjugated FITC-labeled tracer to the biotinylated extracellular matrix proteins immobilized on the bottom of culture dishes after the EC barrier is compromised by treatment with a barrier-disruptive agonist. XPerT permeability assays were performed in 96-well plates. Visualization of EC monolayer permeability was performed in HPAEC plated on glass cover slips coated with biotinylated gelatin followed by agonist stimulation, incubation with FITC-avidin tracer, fluorescence microscopy, and imaging analysis as previously described (14, 42).

Asef knockdown in human pulmonary EC culture.

To deplete endogenous Asef, an Asef-specific set of three Stealth Select small-interfering RNA (siRNA) duplexes was purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) in ready-to-use, desalted, deprotected, annealed double-strand form. Nonspecific RNA (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO) was used as a control treatment. Transfection of EC with siRNA was performed as previously described (7). After 72 h of transfection, cells were used for experiments or harvested for Western blot verification of specific protein depletion.

Immunofluorescence.

Endothelial monolayers plated on glass cover slips were subjected to immunofluorescence staining as described previously (5). Texas red phalloidin was used to visualize F-actin. VE-cadherin antibody was used to visualize adherens junctions. Slides were analyzed using a Nikon video imaging system (Nikon Instech, Tokyo, Japan). Images were processed with Image J (National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD) and Adobe Photoshop 7.0 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA) software.

Immunoblotting.

After stimulation with agonist of interest, cells were lysed, and protein extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membrane, and probed with specific antibodies. Immunoreactive proteins were detected with the enhanced chemiluminescent detection system according to the manufacturer's protocol (Amersham, Little Chalfont, UK). Equal protein loading was verified by reprobing membranes with antibody to β-actin or β-tubulin.

Neutrophil migration and ELISAs.

Neutrophil chemotaxis was measured in a 96-well chemotaxis chamber (Neuroprobe, Gaithersburg, MD) as described previously (28). Concentration of interleukin-8 (IL-8) and soluble ICAM-1 was measured in HPAEC conditioned media using an ELISA kit available from R&D Systems.

In vivo model of ALI.

All animal care and treatment procedures were approved by the University of Chicago Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were handled according to the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Generation of Asef−/− mice is described elsewhere (18). Hetero- and homozygous Asef−/− mice were fertile and indistinguishable from their wild-type littermates based on growth rates, external appearance, and pathological examination of internal organs. Absence of Asef appeared to be compatible with normal physiological functioning of mice except for modest impairment of retinal angiogenesis in neonatal mice and reduced angiogenic potential in adult mice (18). Adult male Asef−/− mice and matching wild-type controls, 8–10 wk old, with average weight 20–25 g were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (75 mg/kg) and acepromazine (1.5 mg/kg). HGF (10 μg/kg) was first administered intravenously via jugular vein followed by intratracheal instillation of bacterial LPS (0.7 mg/kg; Escherichia coli O55:B5, it) or saline (∼15 min after onset of HGF injection). Second HGF injection to maintain HGF circulating levels was performed 5 h after LPS challenge. After 24 h, animals were killed under anesthesia.

Evaluation of lung injury parameters.

After the experiment, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed using 1 ml of sterile Hanks' balanced saline buffer. The BAL protein concentration was determined by the BCATM Protein Assay kit (Thermo Scientific, Pittsburg, PA). BAL inflammatory cell counting was performed using a standard hemacytometer technique (6, 16). Total lung myeloperoxidase (MPO) content was determined from homogenized lungs as described elsewhere (29). For analysis of LPS-induced lung vascular leak, Evans blue dye (30 ml/kg) was injected into the external jugular vein 2 h before termination of the experiment. Measurement of Evans blue accumulation in the lung tissue was performed by spectrofluorimetric analysis of lung tissue lysates according to the protocol described previously (30, 31). For histological assessment of lung injury, the lungs were harvested without lavage collection and fixed in 10% formaldehyde. After fixation, the lungs were embedded in paraffin, cut into 5-μm sections, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Sections were evaluated at ×40 magnification.

Statistical analysis.

Results are presented as means ± SD of three to six independent experiments. Stimulated samples were compared with controls by unpaired Student's t-test. For multiple-group comparisons, a one-way ANOVA, followed by the post hoc Tukey test, were used. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

HGF attenuates endothelial hyperpermeability induced by LPS.

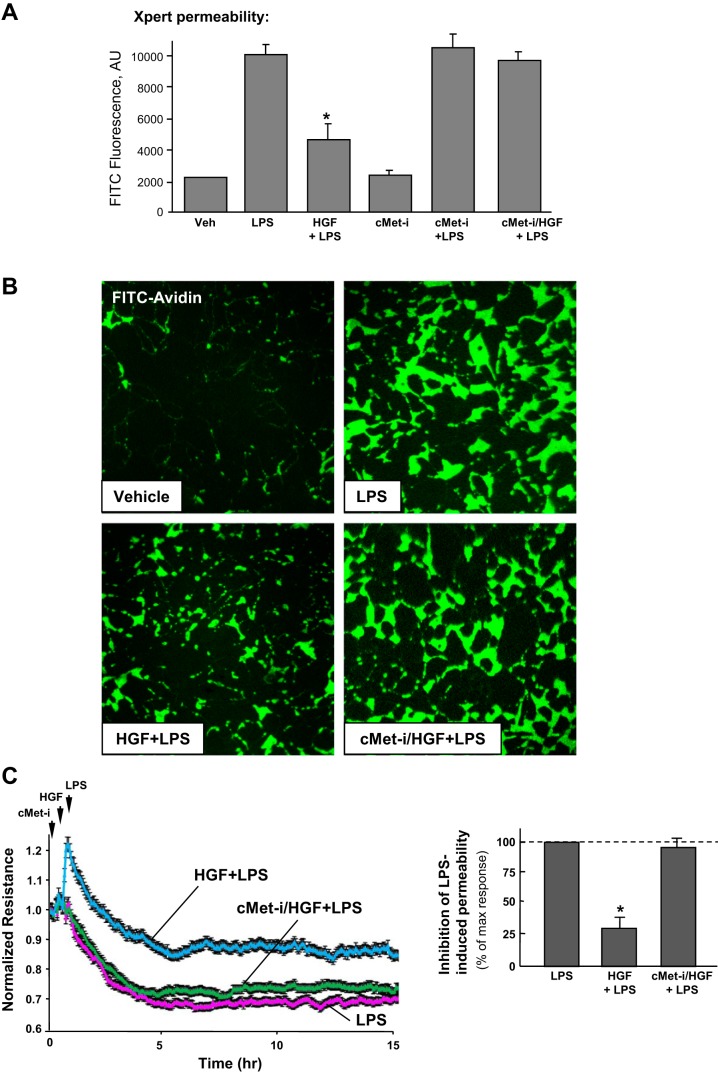

Effects of HGF on LPS-induced lung EC monolayer permeability for macromolecules associated with septic inflammation were analyzed using an express permeability testing assay developed by our group and described in materials and methods (14). LPS significantly increased EC monolayer permeability for FITC-labeled avidin, whereas HGF attenuated LPS barrier disruptive effects (Fig. 1, A and B). HGF protective effect was abolished by cell pretreatment with the pharmacological inhibitor of c-Met receptor, carboxamide. The results show no effect of inhibitor alone (without HGF administration) on basal and LPS-induced EC permeability. Visualization of permeability sites in the LPS-challenged EC monolayers showed penetration of fluorescent probe via weakened cell-cell junctions and LPS-induced paracellular gaps. HGF pretreatment of EC monolayers before LPS challenge markedly decreased penetration of FITC-labeled avidin through intercellular junctions (Fig. 1B). Effects of HGF on EC dysfunction induced by LPS were further examined using the measurements of transendothelial electrical resistance. HPAEC were pretreated with HGF followed by incubation with LPS for up to 15 h. HGF dramatically attenuated disruptive effects of LPS (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Effect of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) on lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced endothelial cell (EC) permeability. A and B: human pulmonary artery endothelial cells (HPAEC) grown in 96-well plates (A) or on glass cover slips (B) with immobilized biotinylated gelatin (0.25 mg/ml) were treated with vehicle or HGF (50 ng/ml, 15 min) with or without pretreatment with cell-permeable c-Met kinase inhibitor (cMet-i, 50 nM carboxamide, 30 min), followed by challenge with LPS (300 ng/ml, 5 h) and addition of FITC-avidin (25 μg/ml, 3 min). Unbound FITC-avidin was removed, and FITC fluorescence was measured. XPerT, express micromolecule permeability testing assay. Data are expressed as means ± SD of 4 independent experiments; *P < 0.05 vs. LPS alone. C: HPAEC plated on microelectrodes were treated with HGF (50 ng/ml, 15 min) with or without pretreatment with c-Met kinase inhibitor (50 nM carboxamide, 30 min), followed by stimulation with LPS (300 ng/ml), as shown by arrows. Transendothelial electrical resistance (TER) was monitored over 15 h. Permeability data are expressed as means ± SD of 6 independent experiments; *P < 0.05.

HGF suppresses LPS-induced EC monolayer disruption.

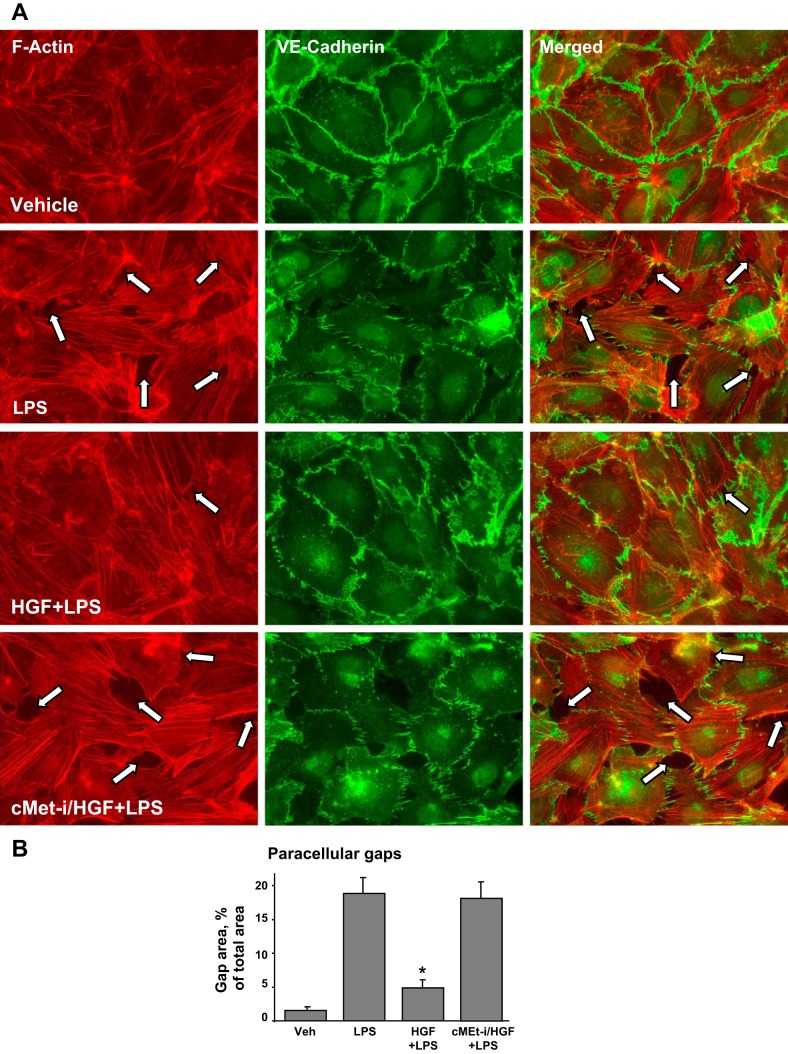

Effects of HGF on LPS-induced EC monolayer disruption were next examined by analysis of actin cytoskeleton remodeling and changes in adherens junction integrity. LPS induced formation of actin stress fibers and cell contraction associated with appearance of paracellular gaps after 5 h of LPS treatment, the time point corresponding to a pronounced increase in EC monolayer permeability. These changes were reduced by EC pretreatment with HGF (Fig. 2, A and B). Immunofluorescence analysis of adherens junction remodeling confirmed disruption of cell-cell contacts in response to LPS. In turn, HGF pretreatment preserved the continuous adherens junction pattern in LPS-challenged EC (Fig. 2A). Pretreatment with c-Met inhibitor abrogated HGF protective effects against LPS-induced disruption of EC monolayer integrity. These results reflect potent protective effects of HGF against EC barrier dysfunction caused by endotoxin derived from gram-negative bacteria.

Fig. 2.

Effect of HGF on LPS-induced cytoskeletal remodeling and gap formation. Endothelial monolayers were treated with HGF (50 ng/ml, 15 min) with or without pretreatment with carboxamide (50 nM cMet-i, 30 min) and stimulated with LPS (300 ng/ml) for 5 h. A: analysis of actin cytoskeletal rearrangement and adherens junctions remodeling was performed by immunofluorescence staining with Texas red phalloidin and VE-cadherin, respectively. Paracellular gaps are marked by arrows. B: quantitative analysis of paracellular gap formation in control and treated HPAEC. Data are expressed as means ± SD of 4 independent experiments; *P < 0.05 vs. LPS alone.

HGF inhibits LPS-induced activation of inflammatory signaling.

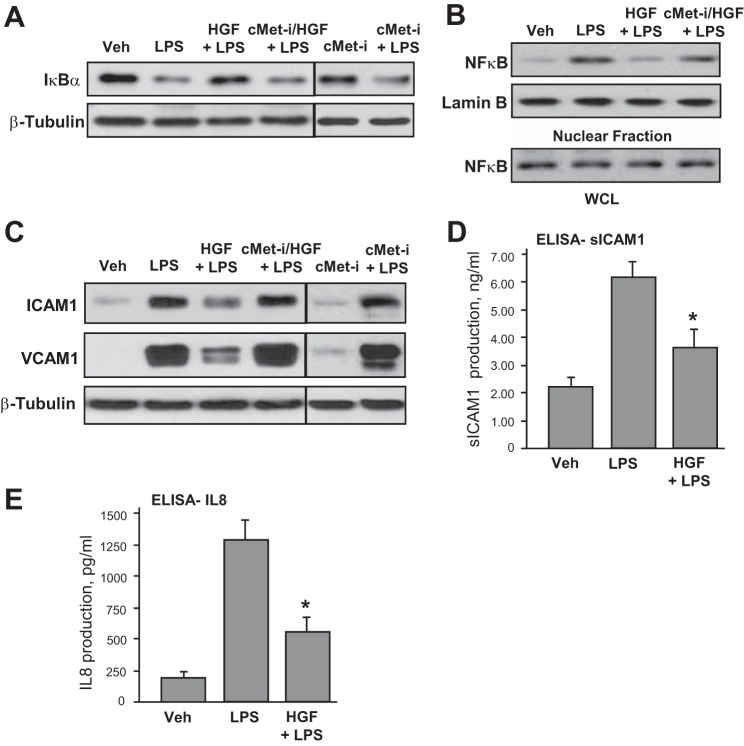

Attenuation of LPS-induced barrier disruptive and inflammatory signaling by HGF was further examined. LPS stimulation of pulmonary EC triggered the canonical inflammatory pathway and induced degradation of IκBα inhibitory subunit leading to activation of NF-κB signaling. These effects were inhibited by HGF (Fig. 3A). LPS-induced activation of NF-κB-dependent inflammatory gene expression requires nuclear translocation of NF-κB p65 subunit. Subcellular fractionation assays (Fig. 3B) showed nuclear translocation of NF-κB after LPS challenge that was attenuated by HGF.

Fig. 3.

Effects of HGF on LPS-induced inflammatory signaling. A and B: HPAEC were treated with vehicle or HGF (50 ng/ml, 15 min), with or without pretreatment with carboxamide (50 nM cMet-i, 30 min), followed by stimulation with LPS (300 ng/ml) for 1 h. A: degradation of IκBα was detected using antibodies against nonphosphorylated protein. Equal protein loading was confirmed by determination of β-tubulin content in total cell lysates. B: fractionation assay was performed, and the content of NF-κB in the nuclear fraction was determined by Western blot analysis with specific antibodies. Determination of NF-κB content in corresponding total cell lysates and lamin B content in nuclear fractions were used to ensure equal loading. C and D: HPAEC were pretreated with HGF (50 ng/ml, 15 min) with or without carboxamide (50 nM cMet-i, 30 min), followed by stimulation with LPS (300 ng/ml) for 6 h. C: intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1 and vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM)-1 expression was detected by Western blot with corresponding antibody. β-Tubulin staining was used as a normalization control. Soluble ICAM-1 (D) and IL-8 production (E) in EC preconditioned medium was evaluated by ELISA. *P < 0.05 vs. LPS alone.

Activation of vascular endothelium by inflammatory agents stimulates neutrophil adhesion to the vascular EC lining followed by neutrophil transmigration through the EC monolayer and neutrophil recruitment to the inflamed lung tissue.

The following studies evaluated effects of HGF on EC inflammatory activation. Western blot experiments showed the time-dependent, LPS-induced expression of EC surface adhesion molecules ICAM-1 and VCAM-1, which are involved in neutrophil adhesion. This LPS effect was attenuated by HGF pretreatment (Fig. 3C). In complementary studies, a content of soluble ICAM-1 was measured in HPAEC conditioned media. Similarly to analysis of ICAM-1 expression, LPS treatment caused elevation of soluble ICAM-1, whereas HGF inhibited this increase (Fig. 3D). We next measured IL-8 content in preconditioned medium collected from control and stimulated EC. LPS induced IL-8 expression by pulmonary EC, which was abolished by HGF pretreatment (Fig. 3E). Collectively, these data suggest potent protective effects of HGF against LPS-induced activation of inflammatory signaling in pulmonary endothelium.

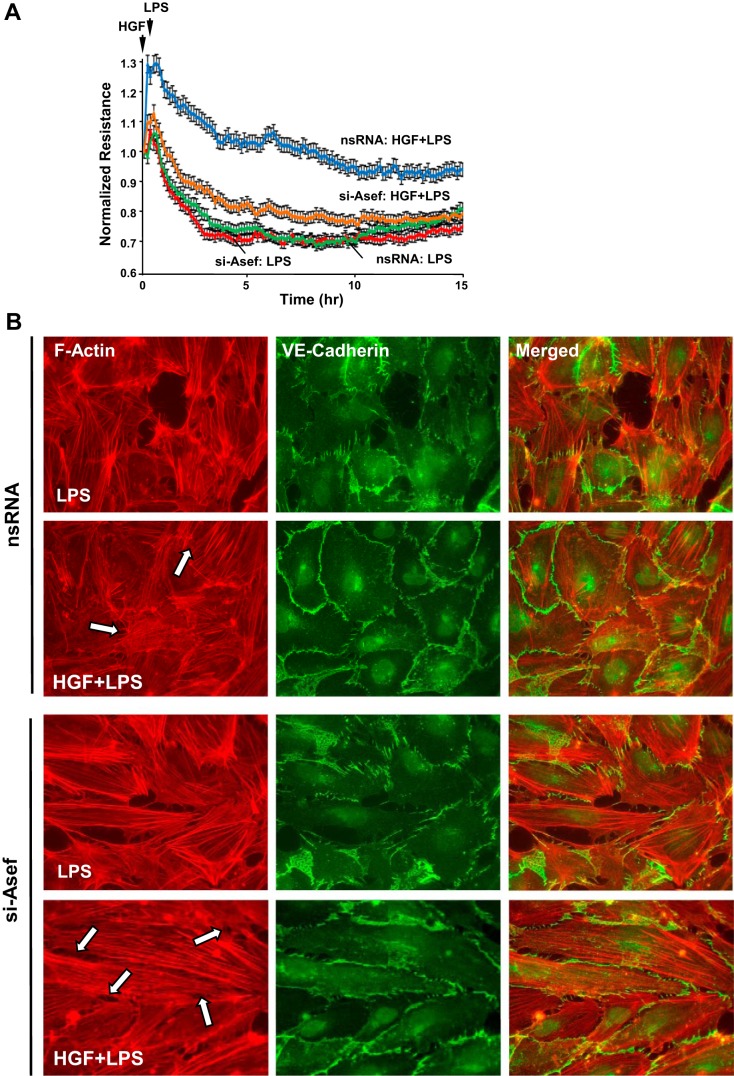

Asef mediates HGF-induced protection of EC barrier.

Previous works demonstrated the role of HGF-activated Rac1 signaling in EC barrier enhancement. The following experiments tested involvement of novel Rac1-specific guanine nucleotide exchange factor Asef in the HGF-induced downregulation of inflammatory signaling. siRNA-induced Asef knockdown did not significantly change the permeability response to LPS alone but attenuated protective effects of HGF against LPS-induced permeability (Fig. 4A). EC treatment with Asef-specific siRNA resulted in 80–90% reduction of Asef endogenous protein content, as shown below (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 4.

Effects of APC-stimulated guanine nucleotide exchange factor (Asef) knockdown on HGF-induced EC barrier protection. HPAEC were transfected with nonspecific RNA (nsRNA) or with Asef-specific small-interfering RNA (siRNA) for 72 h. A: cells plated on microelectrodes were treated with vehicle or HGF (50 ng/ml, 15 min) followed by LPS stimulation (300 ng/ml). TER was monitored over 15 h. B: cells were treated with vehicle or HGF followed by LPS stimulation (300 ng/ml, 5 h). Actin and adherens junction remodeling were assessed by double-immunofluorescence staining of F-actin with Texas red phalloidin and VE-cadherin. Paracellular gaps are marked by arrows.

Fig. 5.

Effects of Asef knockdown on HGF-mediated protection against LPS-induced inflammatory signaling. A and B: HPAEC were treated with HGF (50 ng/ml, 15 min) followed by stimulation with LPS (300 ng/ml) for 1 h. A: degradation of IκBα was detected using antibodies against nonphosphorylated protein. Equal protein loading was confirmed by determination of β-tubulin content in total cell lysates. siRNA-induced Asef protein depletion was monitored by Western blot analysis of cell lysates with Asef antibody (bottom). Bar graph represents results of quantitative densitometry analysis; *P < 0.05, n = 5. B: NF-κB nuclear translocation was assessed by immunofluorescence staining with specific antibody. DAPI staining was used to visualize cell nuclei. C and D: EC were treated with HGF (50 ng/ml, 15 min) followed by stimulation with LPS (300 ng/ml) for 6 h. C: ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression was detected by Western blot with corresponding antibody. β-Tubulin staining was used as a normalization control. D: soluble ICAM-1 (sICAM-1) production in EC preconditioned medium was evaluated by ELISA. *P < 0.05 vs. nsRNA.

The role of Asef in the HGF barrier protective effects was further assessed by analysis of cytoskeletal remodeling in control and Asef-depleted HPAEC stimulated with LPS with or without HGF pretreatment. Similarly to nontransfected EC (Fig. 2), HGF pretreatment attenuated LPS-induced stress fiber formation and disruption of monolayer integrity in cells transfected with nonspecific RNA. These effects of HGF were inhibited by Asef knockdown (Fig. 4B).

Asef knockdown also abolished protective effects of HGF against LPS-induced activation of NF-κB signaling (Fig. 5, A and B). siRNA-induced Asef protein knockdown was confirmed by Western blot with Asef-specific antibody (Fig. 5A, bottom). Moreover, Asef knockdown attenuated the protective effect of HGF against LPS-induced ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression (Fig. 5C) and release of soluble ICAM-1 (Fig. 5D), a hallmark of inflammatory activation of endothelial cells.

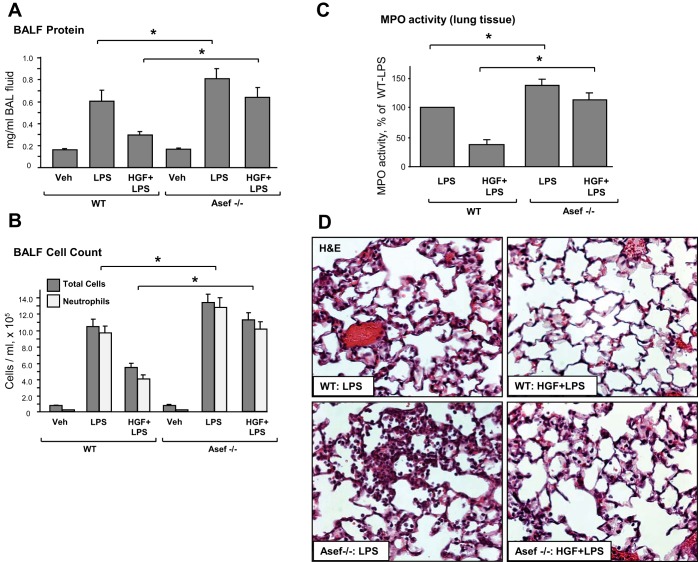

Asef mediates protective effects of HGF in vivo.

The studies in pulmonary EC culture described above demonstrate a critical role for Asef as a key mediator of HGF-induced signaling. The role of Asef in the HGF-induced lung protection was further investigated in the model of ALI induced by intratracheal instillation of LPS (9, 50). Asef−/− mice (18) and matching wild-type controls were injected with HGF or vehicle (iv) followed by LPS intratracheal administration in the next 10–15 min. The HGF group also received a second HGF intravenous injection 5 h after LPS instillation. Control mice were treated with vehicle (saline solution) alone. After LPS challenge (24 h), lung injury was evaluated by measurements of BAL cell count, protein concentration, myeloperoxidase activity, histological analysis of lung sections, and measurements of Evans blue accumulation in the lung tissue. In both the wild-type and Asef−/− mice, LPS instillation caused pronounced lung inflammation, reflected by elevation of protein content (Fig. 6A) and total cell and neutrophil count (Fig. 6B) in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF). Compared with wild-type controls, Asef knockout mice developed more severe lung injury in response to LPS. In wild-type controls, HGF exhibited strong protective effects. Importantly, HGF protective effects against LPS-induced increases in BALF protein content and cell count observed in wild-type controls were attenuated in Asef−/− mice.

Fig. 6.

Role of Asef in HGF-mediated protection against LPS-induced lung inflammation in vivo. Wild-type and Asef−/− mice were treated with LPS (0.7 mg/kg it) with or without concurrent HGF administration (10 μg/kg iv at 0 and 5 h after LPS instillation). Control animals were treated with sterile saline solution alone. A–B: protein concentration (A) and total cell and neutrophil count (B) were determined in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) collected 24 h after treatments. Data are expressed as means ± SD, n = 6–10/condition; *P < 0.05. C: myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity was measured in lung tissue homogenates. Data are expressed as means ± SD, n = 4/condition; *P < 0.05. D: whole lungs were fixed in 10% formalin and used for histological evaluation by hematoxylin and eosin staining; n = 4–6/condition; magnification ×40.

Severity of lung injury and inflammation was also monitored by measurements of MPO activity, a marker of neutrophil activation and tissue oxidative stress. LPS significantly increased MPO activity measured in tissue homogenates (Fig. 6C). HGF decreased MPO activity in the lungs of LPS-exposed wild-type mice, whereas in the Asef−/− mice this effect was abolished. Histological analysis of lung tissue sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin revealed that, in wild-type and Asef−/− mice, LPS caused alveolar wall thickening and increased leukocyte infiltration into the lung interstitium and alveolar space (Fig. 6D). Pretreatment with HGF markedly attenuated LPS-induced inflammatory cell infiltration in the wild-type mice but failed to induce comparable protective effects in Asef knockouts.

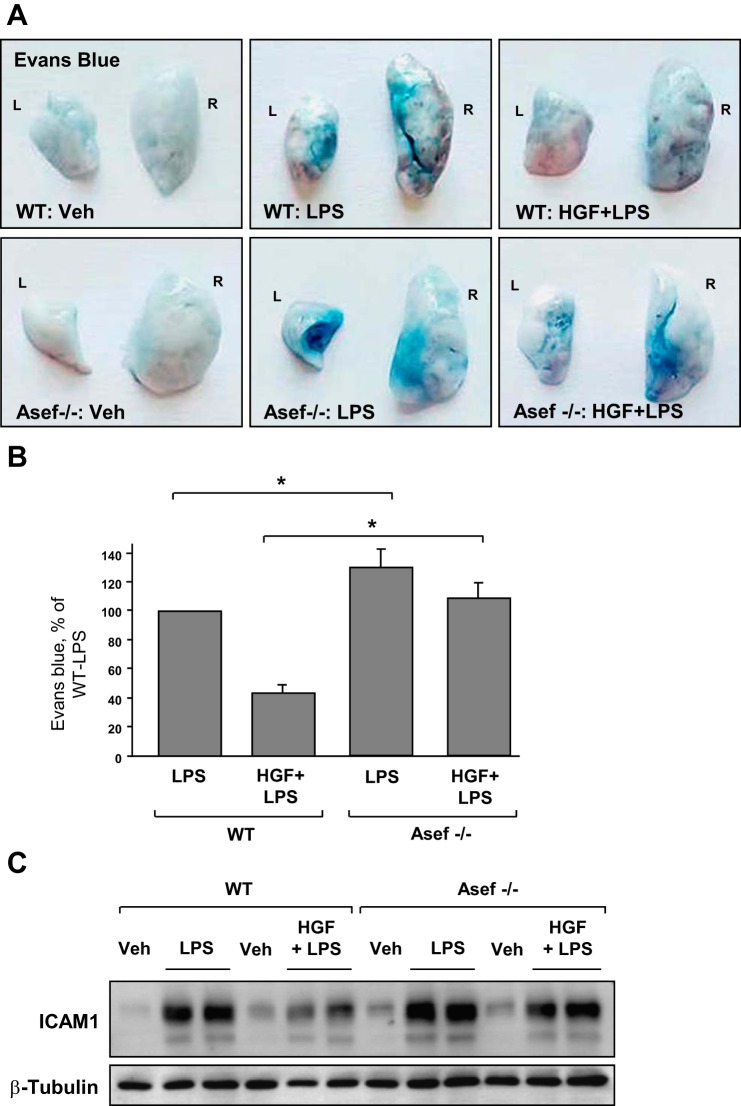

The protective effects of HGF against LPS-induced lung vascular leak in wild-type and Asef−/− mice were further assessed by measurement of Evans blue leakage into the lung tissue. LPS induced noticeable Evans blue dye accumulation in the lung parenchyma that was significantly decreased by HGF in wild-type controls (Fig. 7A). Protective effects of HGF were suppressed in the Asef−/− mice. These results were further confirmed by quantitative analysis of Evans blue-labeled albumin extravasation in the lung preparations (Fig. 7B). In consistence with cell culture studies, HGF treatment inhibited LPS-induced ICAM-1 expression in the lung, as detected by Western blot analysis of lung tissue homogenates from wild-type mice. This effect was abolished in Asef−/− mice (Fig. 7C).

Fig. 7.

Role of Asef in HGF-mediated protection against LPS-induced vascular leak and EC inflammatory activation in vivo. Wild-type and Asef−/− mice were treated with LPS (0.7 mg/kg it) with or without concurrent HGF administration (10 μg/kg iv at 0 and 5 h after LPS instillation). Control animals were treated with sterile saline solution alone. A and B: lung vascular permeability was assessed by Evans blue accumulation in the lung tissue (A). Left (L) and right (R) lung lobes are marked. The quantitative analysis of Evans blue-labeled albumin extravasation was performed by spectrophotometric analysis of Evans blue extracted from the lung tissue samples; n = 4/condition; *P < 0.05 (B). C: ICAM-1 expression after LPS challenge with or without HGF treatment was determined in lung tissue homogenates by Western blot analysis with specific antibodies. Equal protein loading was confirmed by membrane reprobing with β-tubulin antibodies.

Taken together, these results demonstrate the role for Asef in the mediation of HGF effects and further support anti-inflammatory and barrier-protective effects of HGF against septic inflammation and vascular endothelial barrier dysfunction in cell culture and the animal models of LPS-induced lung injury.

DISCUSSION

HGF is produced by endothelial cells, alveolar macrophages, fibroblasts, bronchial cells, and even by activated alveolar neutrophils (22). HGF levels are elevated in lung fluid of patients with ALI, suggesting the role of HGF in lung repair under inflammatory conditions (44). This study shows that, in addition to protecting against agonist-induced EC permeability via downregulation of Rho-mediated barrier disruptive signaling (3), HGF is capable of suppressing the LPS-induced endothelial inflammatory activation and barrier disruption.

Rac-specific GEF Asef has been recently described in epithelial cell lines and shown to be involved in HGF-induced epithelial cell adhesion and migration (35). Asef expression increased the renal tubules as a cellular response to injury necessary for cell proliferation and repair of renal tubules (12). Molecular inhibition of Asef decreased the rates of basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF)- and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-induced endothelial cell migration and partially suppressed angiogenesis (18). The role of Asef in modulation of inflammation has been unknown.

This study shows a novel mechanism of HGF anti-inflammatory effect via Asef-dependent attenuation of EC barrier disruption, expression of adhesion molecules ICAM-1 and VCAM-1, and production of interleukin-8. This mechanism is further supported by experiments with Asef knockdown in human pulmonary EC and Asef−/− mice. Asef knockouts developed more severe lung injury in response to LPS, whereas barrier protective and anti-inflammatory effects of HGF in the LPS model were suppressed. In support of the key role of Asef in the HGF-induced protective mechanism described in this study, Asef ablation also caused nearly complete inhibition of Rac activation in response to VEGF and bFGF in cells isolated from Asef−/− mice, leading to impaired cell migration and tube formation, although expression of other Rac-specific GEFs was not affected (18).

A role of Rac-Rho cross talk in control of lung inflammation and injury is not well understood. LPS-induced activation of Rho signaling occurs in parallel to stimulation of canonical inflammatory cascades (15, 41, 48, 49). One mechanism of LPS-induced Rho activation involves release from microtubules and activation of Rho-specific activator GEF-H1 (21). In turn, activation of the Rho pathway further enhances LPS-induced activation of NF-kB and stress kinases. This amplification of inflammatory signaling may be ceased by pharmacological inhibition of Rho kinase activity (8, 39, 47, 48). Alternatively, molecular inhibition of GEF-H1 in vitro and gene ablation in vivo attenuated LPS-induced EC permeability and suppressed LPS-induced upregulation of ICAM-1, IL-8, and neutrophil adhesion (21). The precise mechanism of Asef-dependent attenuation of inflammation requires further investigation. However, based on our present and published data, and Asef function as Rac activator, we speculate that Asef activation may shift the balance between Rac and Rho activities toward Rac, leading to the reduction of Rho pathway input into the LPS-induced inflammatory response.

Our results demonstrate potent, but incomplete, inhibition of HGF anti-inflammatory and barrier protective effects by Asef knockdown in EC culture and in Asef knockout mice. In consistence with this observation, retinal angiogenesis was also modestly impaired in Asef−/− mice, which, similarly to our observations, did not show other significant abnormalities. These phenotypic features of Asef−/− mice raise the possibility that Asef function might be backed by other members of Dbl family guanine nucleotide exchange factors. Indeed, HGF may activate other Rac specific GEF Tiam1, shown to stimulate Rac activity and cortical actin remodeling, enhance endothelial cell adherens junctions, and strengthen the endothelial barrier (3, 38). Therefore, activation of Tiam1 by HGF may complement anti-inflammatory effects of Asef. This signaling cross talk warrants further investigation.

Involvement of multiple GEFs in Rac1 GTPase activation by various factors may be dictated by necessity for space- and time-dependent orchestration of Rac activity in response to agonist-induced or mechanical stimulation. Therefore, Asef and other GEFs such as Tiam1 may be involved in different steps of HGF-induced Rac regulation. Alternatively, activation of two or more GEFs by HGF may provide fine tuning of the levels of Rac activation by specific barrier protective agonists, mechanical signals, or disruption of monolayer integrity. Further studies are warranted to investigate the GEF interplay in the HGF-induced preservation of EC barrier and attenuation of inflammatory activation.

In summary, this study shows a novel mechanism of anti-inflammatory HGF effects on the LPS-induced endothelial inflammatory activation and lung injury mediated by HGF-activated Rac-specific GEF Asef. These results suggest that targeted activation of Rac-specific GEFs such as Asef may attenuate lung injury induced by bacterial pathogens and accelerate restoration of lung function.

GRANTS

This work was supported by Grant HL-107920 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: F.M., A.M., and N.M. performed experiments; F.M., A.M., N.M., and A.A.B. analyzed data; F.M., A.M., N.M., and A.A.B. prepared figures; F.M. drafted manuscript; F.M., A.M., N.M., G.M.M., Y.K., T.A., and A.A.B. approved final version of manuscript; G.M.M., T.A., and A.A.B. edited and revised manuscript; Y.K., T.A., and A.A.B. interpreted results of experiments; A.A.B. conception and design of research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aoki M, Morishita R, Taniyama Y, Kaneda Y, Ogihara T. Therapeutic angiogenesis induced by hepatocyte growth factor: potential gene therapy for ischemic diseases. J Atheroscler Thromb 7: 71–76, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Birukova AA, Adyshev D, Gorshkov B, Bokoch GM, Birukov KG, Verin AA. GEF-H1 is involved in agonist-induced human pulmonary endothelial barrier dysfunction. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 290: L540–L548, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Birukova AA, Alekseeva E, Mikaelyan A, Birukov KG. HGF attenuates thrombin-induced permeability in the human pulmonary endothelial cells by Tiam1-mediated activation of the Rac pathway and by Tiam1/Rac-dependent inhibition of the Rho pathway. FASEB J 21: 2776–2786, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birukova AA, Birukov KG, Smurova K, Adyshev DM, Kaibuchi K, Alieva I, Garcia JG, Verin AD. Novel role of microtubules in thrombin-induced endothelial barrier dysfunction. FASEB J 18: 1879–1890, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birukova AA, Cokic I, Moldobaeva N, Birukov KG. Paxillin is involved in the differential regulation of endothelial barrier by HGF and VEGF. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 40: 99–107, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Birukova AA, Fu P, Chatchavalvanich S, Burdette D, Oskolkova O, Bochkov VN, Birukov KG. Polar head groups are important for barrier protective effects of oxidized phospholipids on pulmonary endothelium. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 292: L924–L935, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birukova AA, Fu P, Xing J, Yakubov B, Cokic I, Birukov KG. Mechanotransduction by GEF-H1 as a novel mechanism of ventilator-induced vascular endothelial permeability. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 298: L837–L848, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Birukova AA, Wu T, Tian Y, Meliton A, Sarich N, Tian X, Leff A, Birukov KG. Iloprost improves endothelial barrier function in lipopolysaccharide-induced lung injury. Eur Respir J 41: 165–176, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Birukova AA, Xing J, Fu P, Yakubov B, Dubrovskyi O, Fortune JA, Klibanov AM, Birukov KG. Atrial natriuretic peptide attenuates LPS-induced lung vascular leak: role of PAK1. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 299: L652–L663, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Birukova AA, Zagranichnaya T, Alekseeva E, Bokoch GM, Birukov KG. Epac/Rap and PKA are novel mechanisms of ANP-induced Rac-mediated pulmonary endothelial barrier protection. J Cell Physiol 215: 715–724, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Birukova AA, Zagranichnaya T, Alekseeva E, Fu P, Chen W, Jacobson JR, Birukov KG. Prostaglandins PGE2 and PGI2 promote endothelial barrier enhancement via PKA- and Epac1/Rap1-dependent Rac activation. Exp Cell Res 313: 2504–2520, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng HT, Juang IP, Chen LC, Lin LY, Chao CH. Association of Asef and Cdc42 expression to tubular injury in diseased human kidney. J Investig Med 61: 1097–1103, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dosquet C, Weill D, Wautier JL. Molecular mechanism of blood monocyte adhesion to vascular endothelial cells. Nouv Rev Fr Hematol Suppl 34: S55–S59, 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dubrovskyi O, Birukova AA, Birukov KG. Measurement of local permeability at subcellular level in cell models of agonist- and ventilator-induced lung injury. Lab Invest 93: 254–263, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Essler M, Staddon JM, Weber PC, Aepfelbacher M. Cyclic AMP blocks bacterial lipopolysaccharide-induced myosin light chain phosphorylation in endothelial cells through inhibition of Rho/Rho kinase signaling. J Immunol 164: 6543–6549, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fu P, Birukova AA, Xing J, Sammani S, Murley JS, Garcia JG, Grdina DJ, Birukov KG. Amifostine reduces lung vascular permeability via suppression of inflammatory signalling. Eur Respir J 33: 612–624, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giannopoulou M, Dai C, Tan X, Wen X, Michalopoulos GK, Liu Y. Hepatocyte growth factor exerts its anti-inflammatory action by disrupting nuclear factor-kappaB signaling. Am J Pathol 173: 30–41, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawasaki Y, Jigami T, Furukawa S, Sagara M, Echizen K, Shibata Y, Sato R, Akiyama T. The adenomatous polyposis coli-associated guanine nucleotide exchange factor Asef is involved in angiogenesis. J Biol Chem 285: 1199–1207, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawasaki Y, Sato R, Akiyama T. Mutated APC and Asef are involved in the migration of colorectal tumour cells. Nat Cell Biol 5: 211–215, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawasaki Y, Senda T, Ishidate T, Koyama R, Morishita T, Iwayama Y, Higuchi O, Akiyama T. Asef, a link between the tumor suppressor APC and G-protein signaling. Science 289: 1194–1197, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kratzer E, Tian Y, Sarich N, Wu T, Meliton A, Leff A, Birukova AA. Oxidative stress contributes to lung injury and barrier dysfunction via microtubule destabilization. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 47: 688–697, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lindsay CD. Novel therapeutic strategies for acute lung injury induced by lung damaging agents: the potential role of growth factors as treatment options. Hum Exp Toxicol 30: 701–724, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu F, Schaphorst KL, Verin AD, Jacobs K, Birukova A, Day RM, Bogatcheva N, Bottaro DP, Garcia JG. Hepatocyte growth factor enhances endothelial cell barrier function and cortical cytoskeletal rearrangement: potential role of glycogen synthase kinase-3beta. FASEB J 16: 950–962, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lucas R, Verin AD, Black SM, Catravas JD. Regulators of endothelial and epithelial barrier integrity and function in acute lung injury. Biochem Pharmacol 77: 1763–1772, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsumoto K, Nakamura T. Emerging multipotent aspects of hepatocyte growth factor. J Biochem (Tokyo) 119: 591–600, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matthay MA, Zimmerman GA, Esmon C, Bhattacharya J, Coller B, Doerschuk CM, Floros J, Gimbrone MA Jr, Hoffman E, Hubmayr RD, Leppert M, Matalon S, Munford R, Parsons P, Slutsky AS, Tracey KJ, Ward P, Gail DB, Harabin AL. Future research directions in acute lung injury: summary of a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute working group. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 167: 1027–1035, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mehta D, Malik AB. Signaling mechanisms regulating endothelial permeability. Physiol Rev 86: 279–367, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meliton AY, Munoz NM, Meliton LN, Binder DC, Osan CM, Zhu X, Dudek SM, Leff AR. Cytosolic group IVa phospholipase A2 mediates IL-8/CXCL8-induced transmigration of human polymorphonuclear leukocytes in vitro (Abstract). J Inflam 7: 14, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meliton AY, Munoz NM, Meliton LN, Birukova AA, Leff AR, Birukov KG. Mechanical induction of group V phospholipase A2 causes lung inflammation and acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 304: L689–L700, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moitra J, Sammani S, Garcia JG. Re-evaluation of Evans Blue dye as a marker of albumin clearance in murine models of acute lung injury. Transl Res 150: 253–265, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nonas S, Birukova AA, Fu P, Xing J, Chatchavalvanich S, Bochkov VN, Leitinger N, Garcia JG, Birukov KG. Oxidized phospholipids reduce ventilator-induced vascular leak and inflammation in vivo (Abstract). Crit Care 12: R27, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ponzetto C, Bardelli A, Zhen Z, Maina F, dalla Zonca P, Giordano S, Graziani A, Panayotou G, Comoglio PM. A multifunctional docking site mediates signaling and transformation by the hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor receptor family. Cell 77: 261–271, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ricard JD, Dreyfuss D, Saumon G. Ventilator-induced lung injury. Eur Respir J Suppl 42: 2s–9s, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosen EM, Goldberg ID. Scatter factor and angiogenesis. Adv Cancer Res 67: 257–279, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sagara M, Kawasaki Y, Iemura SI, Natsume T, Takai Y, Akiyama T. Asef2 and Neurabin2 cooperatively regulate actin cytoskeletal organization and are involved in HGF-induced cell migration. Oncogene 28: 1357–1365, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schaeper U, Gehring NH, Fuchs KP, Sachs M, Kempkes B, Birchmeier W. Coupling of Gab1 to c-Met, Grb2, and Shp2 mediates biological responses. J Cell Biol 149: 1419–1432, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Singleton PA, Chatchavalvanich S, Fu P, Xing J, Birukova AA, Fortune JA, Klibanov AM, Garcia JG, Birukov KG. Akt-mediated transactivation of the S1P1 receptor in caveolin-enriched microdomains regulates endothelial barrier enhancement by oxidized phospholipids. Circ Res 104: 978–986, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Singleton PA, Salgia R, Moreno-Vinasco L, Moitra J, Sammani S, Mirzapoiazova T, Garcia JG. CD44 regulates hepatocyte growth factor-mediated vascular integrity. Role of c-Met, Tiam1/Rac1, dynamin 2, and cortactin. J Biol Chem 282: 30643–30657, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Slotta JE, Braun OO, Menger MD, Thorlacius H. Fasudil, a Rho-kinase inhibitor, inhibits leukocyte adhesion in inflamed large blood vessels in vivo. Inflamm Res 55: 364–367, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith CW. Leukocyte-endothelial cell interactions. Semin Hematol 30: 45–53, 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tasaka S, Koh H, Yamada W, Shimizu M, Ogawa Y, Hasegawa N, Yamaguchi K, Ishii Y, Richer SE, Doerschuk CM, Ishizaka A. Attenuation of endotoxin-induced acute lung injury by the Rho-associated kinase inhibitor, Y-27632. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 32: 504–510, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tian X, Tian Y, Gawlak G, Sarich N, Wu T, Birukova AA. Control of vascular permeability by atrial natriuretic peptide via GEF-H1-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem 289: 5168–5183, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tomita N, Morishita R, Higaki J, Ogihara T. Novel molecular therapeutic approach to cardiovascular disease based on hepatocyte growth factor. J Atheroscler Thromb 7: 1–7, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Verghese GM, McCormick-Shannon K, Mason RJ, Matthay MA. Hepatocyte growth factor and keratinocyte growth factor in the pulmonary edema fluid of patients with acute lung injury. Biologic and clinical significance. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 158: 386–394, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang Q, Doerschuk CM. The signaling pathways induced by neutrophil-endothelial cell adhesion. Antioxid Redox Signal 4: 39–47, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ware LB, Matthay MA. Keratinocyte and hepatocyte growth factors in the lung: roles in lung development, inflammation, and repair. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 282: L924–L940, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu T, Xing J, Birukova AA. Cell-type-specific crosstalk between p38 MAPK and Rho signaling in lung micro- and macrovascular barrier dysfunction induced by Staphylococcus aureus-derived pathogens. Transl Res 162: 45–55, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xiaolu D, Jing P, Fang H, Lifen Y, Liwen W, Ciliu Z, Fei Y. Role of p115RhoGEF in lipopolysaccharide-induced mouse brain microvascular endothelial barrier dysfunction. Brain Res 1387: 1–7, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xing J, Birukova AA. ANP attenuates inflammatory signaling and Rho pathway of lung endothelial permeability induced by LPS and TNFalpha. Microvasc Res 79: 26–62, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xing J, Yakubov B, Poroyko V, Birukova AA. Opposite effects of ANP receptors in attenuation of LPS-induced endothelial permeability and lung injury. Microvasc Res 83: 194–199, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang L, Himi T, Morita I, Murota S. Hepatocyte growth factor protects cultured rat cerebellar granule neurons from apoptosis via the phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase/Akt pathway. J Neurosci Res 59: 489–496, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]