Abstract

Background

Therapeutic hypothermia (TH) improves neurological outcomes after cardiac arrest (CA) and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). Although nitric oxide prevents organ injury induced by ischemia and reperfusion, role of nitric oxide during TH after CPR remains unclear. Here, we examined the impact of endogenous nitric oxide synthesis on the beneficial effects of hypothermia after CA/CPR. We also examined whether or not inhaled nitric oxide during hypothermia further improves outcomes after CA/CPR in mice treated with TH.

Methods

Wild-type (WT) mice and mice deficient for nitric oxide synthase 3 (NOS3−/−) were subjected to CA at 37°C and then resuscitated with chest compression. Body temperature was maintained at 37°C (normothermia) or reduced to 33°C (TH) for 24 hours after resuscitation. Mice breathed air or air mixed with nitric oxide at 10, 20, 40, 60, or 80 ppm during hypothermia. To evaluate brain injury and cerebral blood flow, magnetic resonance imaging was performed in WT mice after CA/CPR.

Results

Hypothermia up-regulated the NOS3-dependent signaling in the brain (n=6–7). Deficiency of NOS3 abolished the beneficial effects of hypothermia after CA/CPR (n=5–6). Breathing nitric oxide at 40 ppm improved survival rate in hypothermia-treated NOS3−/− mice (n=6) after CA/CPR compared to NOS3−/− mice that were treated with hypothermia alone (n=6, P<0.05). Breathing nitric oxide at 40 (n=9) or 60 (n=9) ppm markedly improved survival rates in TH-treated WT mice (n=51) (both P<0.05 vs TH-treated WT mice). Inhaled nitric oxide during TH (n=7) prevented brain injury compared to TH alone (n=7) without affecting cerebral blood flow after CA/CPR (n=6).

Conclusions

NOS3 is required for the beneficial effects of TH. Inhaled nitric oxide during TH remains beneficial and further improves outcomes after CA/CPR. Nitric oxide breathing exerts protective effects after CA/CPR even when TH is ineffective due to impaired endogenous nitric oxide production.

Introduction

Sudden cardiac arrest (CA) is a leading cause of death worldwide.1 Out-of-hospital CA (OHCA) claims the lives of an estimated 310,000 Americans each year.2 Despite advances in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) methods, only about 10% of adults treated for OHCA survive to hospital discharge, and up to 60% of survivors have moderate to severe cognitive deficits 3 months after resuscitation.3 Most of the post-CA mortality and morbidity is caused by global ischemic brain injury.4 To date, no pharmacological agent is available to improve the outcome after CA/CPR.

Although therapeutic hypothermia (TH) confers significant neuroprotective effects when applied for 12–24 hours after ventricular fibrillation-induced OHCA in adults, TH has been shown to benefit, at most, 20% of victims in whom return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) is achieved.5,6 It is unknown why many patients do not benefit from TH after OHCA. Elucidating the mechanisms responsible for the protective effects of TH will enable not only optimization of TH but also development of other novel therapeutic strategies to improve the outcome after CA/CPR.

Nitric oxide is produced by nitric oxide synthases (NOS1, NOS2, and NOS3). One of the primary targets of nitric oxide is soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC), which is activated by nitric oxide to generate the second messenger cGMP. cGMP activates cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PKG) which phosphorylates a number of proteins including vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP). Nitric oxide exerts several effects that would be expected to attenuate ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury.7 Studies using mice genetically-deficient for NOS3 have demonstrated that NOS3 reduces I/R injury in multiple organs including brain and heart.8,9 We recently reported that deficiency of NOS3 or the α1 subunit of sGC (sGCα1) worsened outcomes after CA/CPR, whereas cardiomyocyte-specific over-expression of NOS3 rescued NOS3-deficient mice from myocardial and neurological dysfunction and death after CA/CPR.10 However, we did not previously investigate whether NOS3 has protective roles after CA/CPR when animals are treated with TH. Specifically, whether or not the beneficial effects of TH require NOS3 remains to be determined.

Although originally developed as a selective pulmonary vasodilator, inhaled nitric oxide has been shown to have systemic effects in a variety of pre-clinical and clinical studies without causing systemic vasodilation. For example, inhaled nitric oxide attenuates myocardial I/R injury in mice11 and swine,12 and it reduces hepatic I/R injury in patients undergoing liver transplantation.13 We recently reported that inhaled nitric oxide improved the survival rate after CA/CPR in mice.14 However, we have not studied whether or not nitric oxide breathing further improves outcomes after CA/CPR in mice that are also treated with TH.

The primary goal of this study was to determine whether inhaled nitric oxide remains beneficial in mice treated with TH after CA/CPR. We also sought to examine the hypothesis that endogenous nitric oxide synthesis by NOS3 is required for the beneficial effects of TH after CA/CPR.

Materials and Methods

Animals

After approval by the Massachusetts General Hospital Subcommittee on Research Animal Care (Boston, MA), we studied 2- to 3-month-old age and weight-matched male C57BL/6J wild-type (WT) and NOS3-deficient (NOS3−/−, B6.129P2-Nos3tm1Unc/J) mice on a C57BL/6J background.

Animal preparation

Mice were intubated, mechanically ventilated (mini-vent, Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA), and instrumented under anesthesia as previously described.10,14–16 Arterial blood pressure was measured via left femoral arterial line. A microcatheter (PE-10, Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) was inserted into the left femoral vein for drug and fluid administration. Blood pressure and needle-probe electrocardiogram monitoring data were recorded and analyzed with the use of a PC-based data acquisition system.

Murine CPR model

Cardiac arrest and CPR in mice were performed as previously described with some minor modifications.10,14–16 Two different protocols were used in this study.

Protocol 1

To determine whether or not the beneficial effects of hypothermia require NOS3 after CA/CPR, WT mice were subjected to 7.5 minutes of CA, whereas NOS3−/− mice were subjected to 6.5 minutes of CA using the protocol previously described.14 After CA, chest compressions were delivered with a finger at a rate of 300–350 per minute with resumption of mechanical ventilation (FiO2 = 1.0) and continuous i.v. infusion of epinephrine. Core body temperature was maintained at 37°C by a warming lamp after ROSC for 1 hour and then mice were kept in a room temperature to allow spontaneous hypothermia (~33°C). In subgroups of NOS3−/− mice, we examined the effects of nitric oxide inhalation at 40 ppm mixed in air starting at 1 hour after ROSC and continued for 24 or 48 hours in custom-made chambers via an INOvent, NO Delivery System (IKARIA, Hampton, NJ), as previously described.14

Protocol 2

To examine the effects of nitric oxide inhalation in TH-treated mice, WT mice were subjected to a prolonged cardiac arrest of 8 minutes at 37°C. After 8 minutes of CA, chest compressions were delivered at a rate of 300 per minute with a novel mouse CPR device. The mouse CPR device is consist of a controller and an air-driven piston chest compressor and enables chest compression with a uniform rate and force. The core body temperature measured by esophageal temperature probe was maintained at 37°C using a warming lamp for 30 minutes after ROSC, whereupon TH was induced by application of a small ice pack. The core body temperature was then maintained at 33°C for the first 24 hours after CA/CPR and documented using a telemeter system (TA10TA-F20, DSI, St. Paul, MN) in a subgroup of mice. Similarly, blood pressure was measured continuously using a telemeter system (TA11PA-C10, DSI) in another group of mice that were treated with TH or maintained at normothermia after CA/CPR. Mice breathed nitric oxide at 10, 20, 40, 60, or 80 ppm starting 30 minutes after ROSC and continued for 24 hours. In subgroups of mice, effects of nitric oxide inhalation at 40 ppm starting at 2 or 6 hours after ROSC and continued for 24 hours were also examined. Medical grade nitric oxide (INOMAX: NO 800 ppm, balance nitrogen; IKARIA) gas was mixed with 100% oxygen between 30 to 60 minutes after ROSC. Thereafter, mice breathed nitric oxide mixed with air in custom-made chambers.

Measurement of protein levels and phosphorylation

Cerebral cortex tissue were obtained from mice 3 hours after sham operation or CA/CPR and treated with hypothermia or maintained at normothermia. Tissue homogenates were centrifuged and the supernatant proteins were fractionated on Mini-PROTEAN TGX gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and transferred to PVDF membranes. Membranes were blocked for 1 hour in 2% ECL Prime blocking agent (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) and incubated overnight with primary antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology Inc., Danvers, MA, unless otherwise noted) against NOS1 (1:5,000), NOS2 (1:5,000), total NOS3 (1:5,000; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), phospho NOS3 at Ser1177 (1:1,000), phosho NOS3 at Thr495 (1:5,000; BD Biosciences), total (1;1,000) and phospho Akt at Ser473 (1;1,000) and Ser308 (1;1,000), total (1;1,000) and phoshpho 5'-prime-Amp-activated protein kinase α (AMPKα) at Thr172 (1;1,000), total (1;1,000) and phospho VASP at Ser239 (1;1,000), Heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90, 1;10,000), and β-tubulin (1:5,000). Bound antibody was detected with a horseradish peroxidase-linked antibody directed against rabbit IgG (1:5,000) or mouse IgG (1:20,000; Thermo-Pierce, Rockford, IL) and was visualized using chemiluminescence with Lumigen TMA-6 (Lumigen, Inc., Southfield, MI) or Immobilon Western (Millipore, Billerica, MA).

Measurement of nitrite levels

Nitrite levels in serum and brain homogenates were determined by the tri-iodide-based liquid phase chemiluminescence assay (Sievers 280i Nitric Oxide Analyzer, General Electric Company, Boulder, CO), as described previously.17

Acquisition and analysis of MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed 24 hours after CA/CPR in WT mice that were treated with TH alone or TH combined with inhaled nitric oxide at 40 ppm. Imaging employed a 9.4 Tesla magnet and a 4-channel phased array receiver coil inside a volume radio frequency transmitter (Bruker BioSpin Corporation, Billerica, MA). All scans were acquired at an isotropic in-plane resolution of 150 microns with 400-micron coronal slices that covered the brain from olfactory bulb to cerebellum. To search for focal lesions of the type that should appear bright on T2-weighted images, we employed fast spin-echo imaging with 8 echoes per excitation and an effective echo time of 60 ms. In addition, we acquired multiple images with stepped echo time values (10, 30 and 50 ms) using a conventional spin-echo sequence in order to enable calculation of regional T2 values.

Cerebral blood flow measurement after CA/CPR

Cerebral blood flow (CBF) after successful CPR in WT mice were measured by continuous arterial spin labeling (ASL) with MRI as described previously.18 CBF were measured in WT mice in the following order: baseline (20 minutes), inhaled nitric oxide (40 ppm, 10 minutes), baseline (20 minutes), inhaled carbon dioxide (CO2, 10 minutes), and baseline (10 minutes). We used carbon dioxide (CO2 7%, oxygen 21%, and balance nitrogen) as a positive control since carbon dioxide is known to increase CBF based on a previous report.19

Statistical Analysis

All data are expressed as mean±SD. Data were analyzed using unpaired t-test or one-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni post hoc test. Differences in survival rates were analyzed with log-rank test. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA) with two tailed hypothesis. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Permissive spontaneous hypothermia improves survival rate after CA/CPR in WT, but not in NOS3−/−, mice

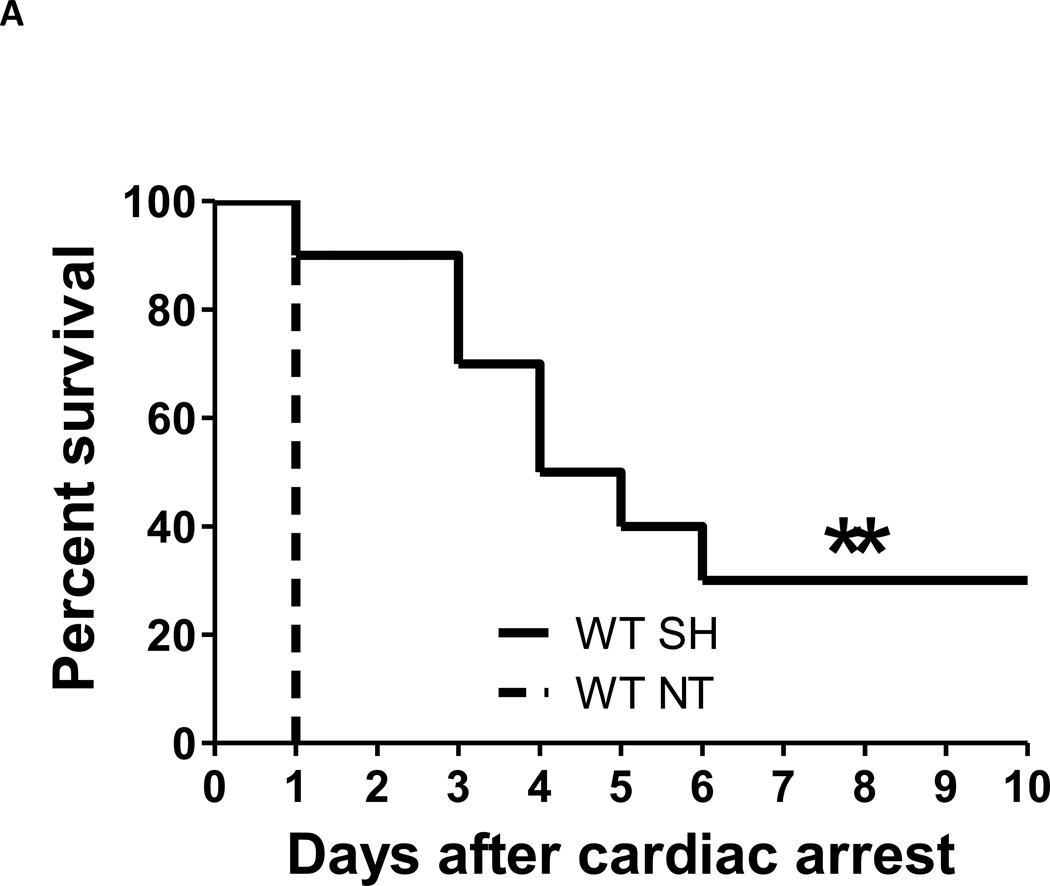

To examine the impact of NOS3 on the beneficial effects of hypothermia after CA/CPR, WT and NOS3−/− mice were subjected to CA/CPR followed by permissive spontaneous hypothermia. When mice were kept in a warmed environment to maintain normothermia for 24 hours, all mice of both genotypes died within 24 hours after CA/CPR. When mice were maintained at room temperature after CA/CPR, their body temperature declined spontaneously (permissive spontaneous hypothermia [~33°C]). Spontaneous hypothermia markedly improved the survival rate in WT mice after 7.5 minutes of CA and subsequent CPR (fig. 1A). In contrast, spontaneous hypothermia failed to improve the survival rate in NOS3−/− mice subjected to 6.5 minutes of CA and CPR (fig. 1B). These results suggest that NOS3 is required for the ability of hypothermia to improve survival rate after CA/CPR.

Fig. 1.

Survival rate during the first 10 days after cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CA/CPR). (A) WT SH, WT mice that were treated with spontaneous hypothermia after CA/CPR. WT NT, WT mice that maintained at normothermia for 24 hours after CA/CPR. N=10 and 5 respectively. **P<0.01 vs WT NT. (B) NOS3−/− SH + iNO for 48 h, NOS3−/− mice that were treated with spontaneous hypothermia combined with inhaled NO at 40 ppm starting at 1 hour after ROSC and continued for 48 hours. NOS3−/− SH + iNO for 24 h, NOS3−/− mice that were treated with spontaneous hypothermia combined with inhaled NO at 40 ppm starting at 1 hour after ROSC and continued for 24 hours. NOS3−/− SH, NOS3−/− mice that were treated with spontaneous hypothermia after CA/CPR. NOS3−/− NT, NOS3−/− mice that maintained at normothermia for 24 hours after CA/CPR. N= 6, 6, 6, and 5 respectively. *P<0.01 vs NOS3−/− NT and NOS3−/− SH, and P<0.05 vs NOS3−/− SH + iNO for 24 h. # P<0.01 vs NOS3−/− NT. Differences in survival rates were analyzed with log-rank test.

Inhaled nitric oxide rescues NOS3−/− mice treated with permissive spontaneous hypothermia after CA/CPR

To examine whether supplementing nitric oxide via inhalation improves the survival rate in NOS3−/− mice, we studied the impact of breathing nitric oxide at 40 ppm on survival after CA/CPR in NOS3−/− mice that were treated with spontaneous hypothermia. Nitric oxide inhalation at 40 ppm starting 1 hour after ROSC and continuing for 24 hours, which markedly improved survival rates in WT mice in a previous study,14 only modesty prolonged the survival time in NOS3−/− mice. In contrast, breathing nitric oxide for 48 hours markedly improved the 10-day survival rate in NOS3−/− mice treated with spontaneous hypothermia (fig. 1B). These results suggest that nitric oxide inhalation improves outcomes after CA/CPR even when hypothermia is ineffective due to deficiency of NOS3.

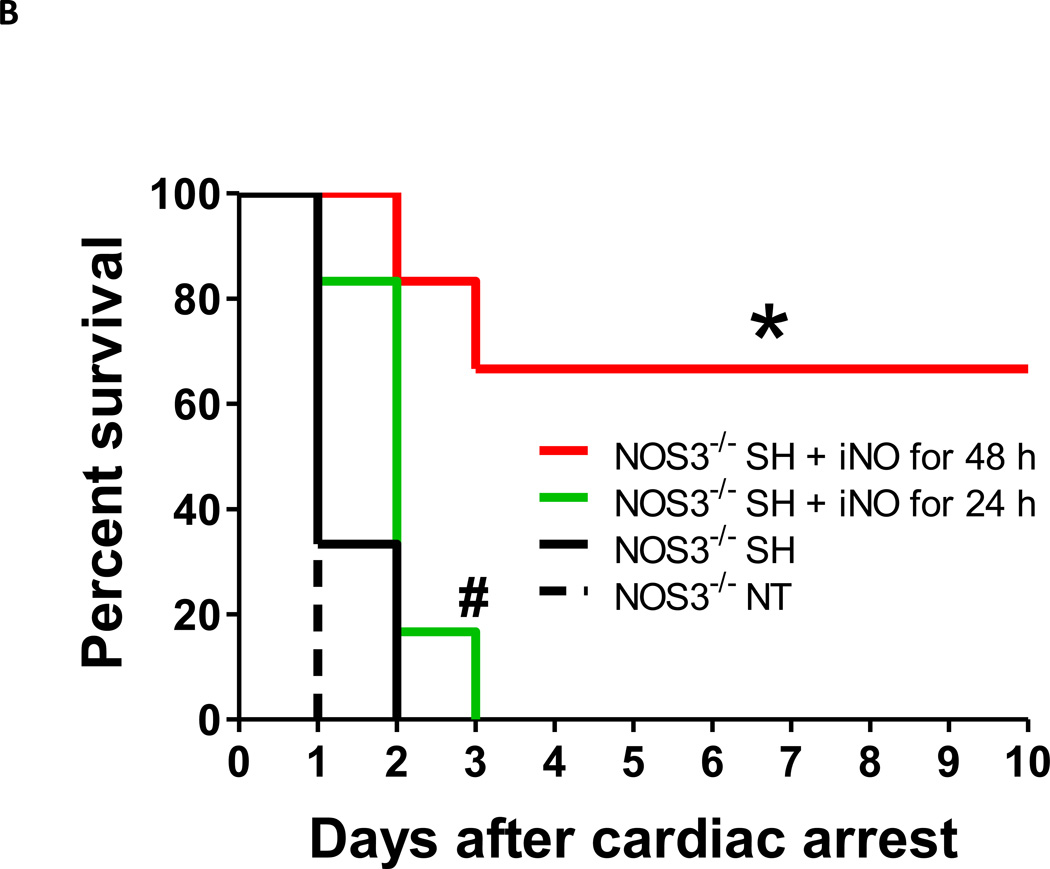

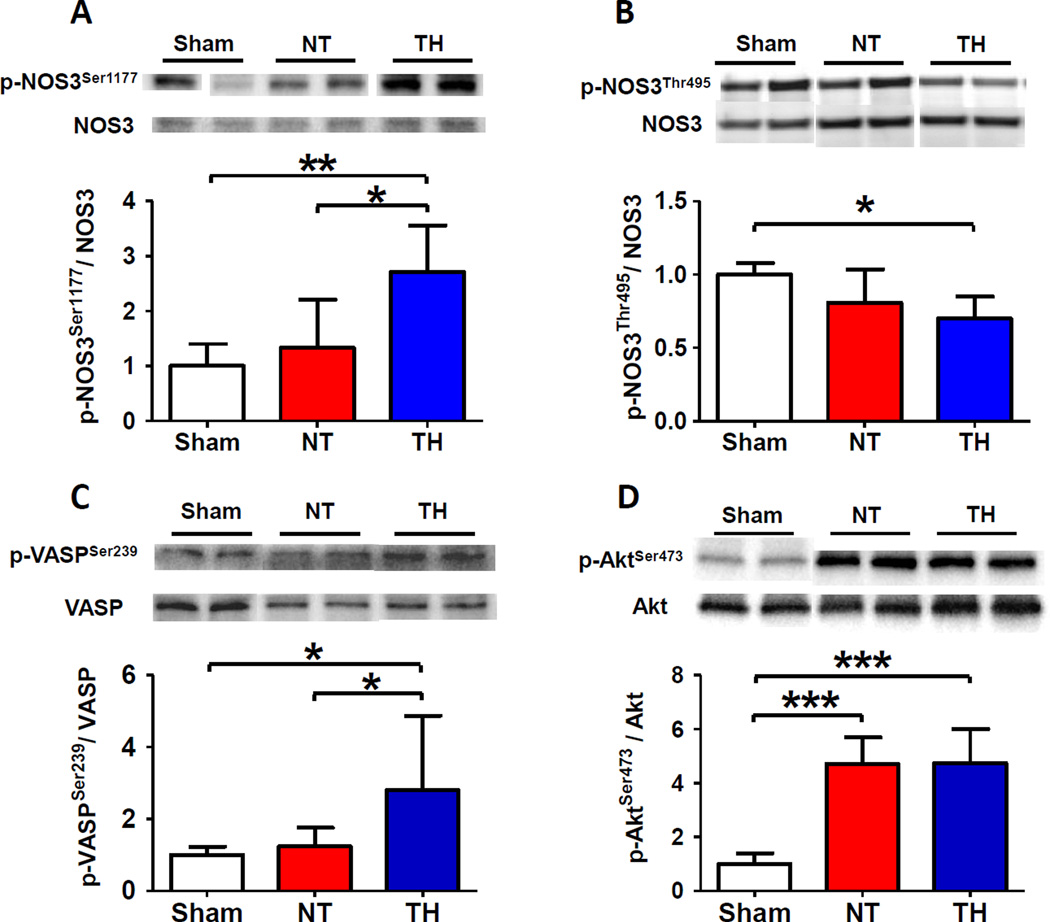

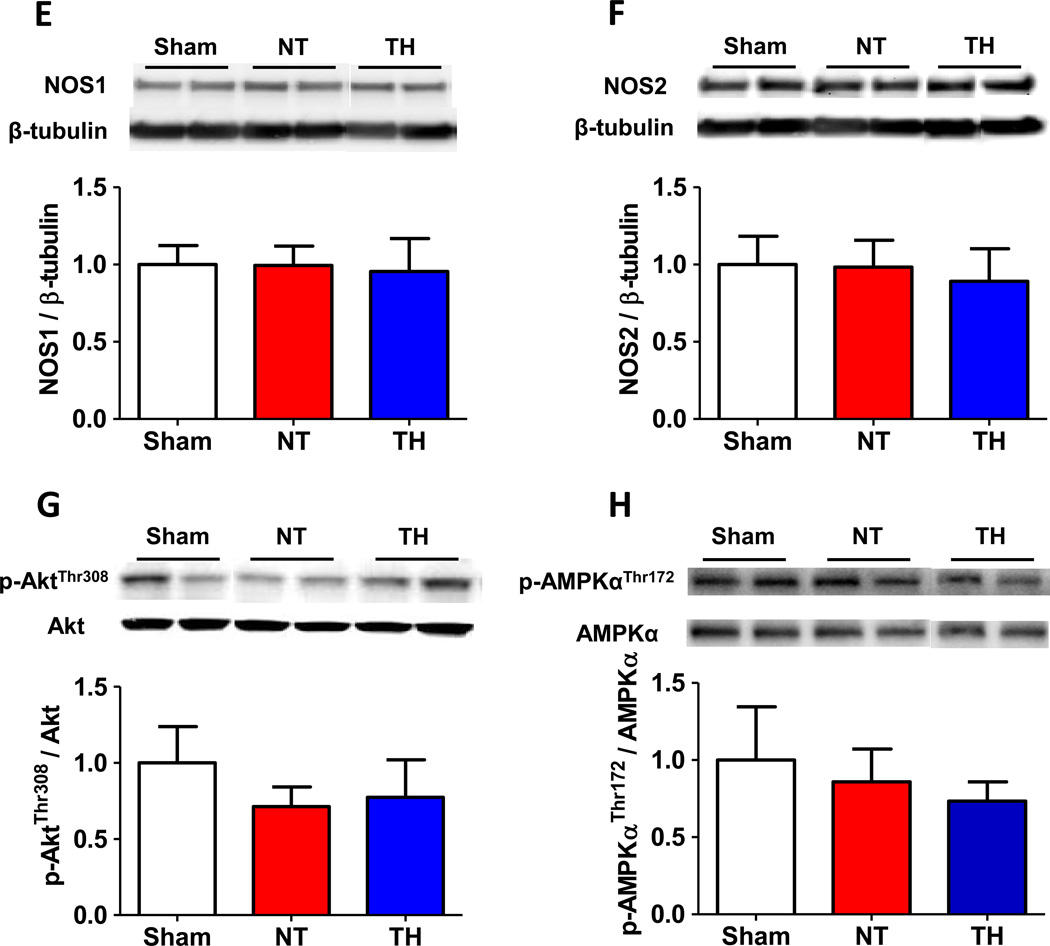

Therapeutic hypothermia up-regulated NOS3-dependent signaling in the brain after CA/CPR

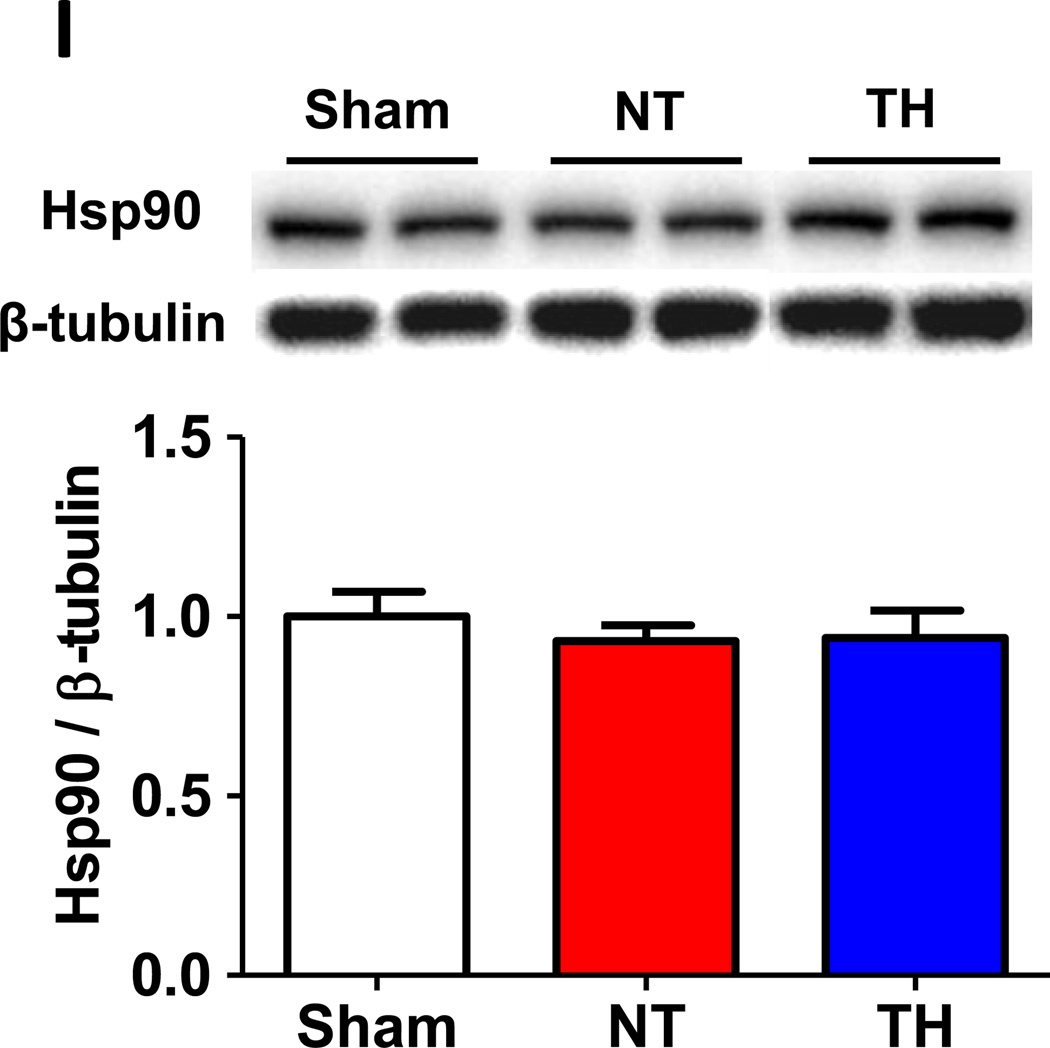

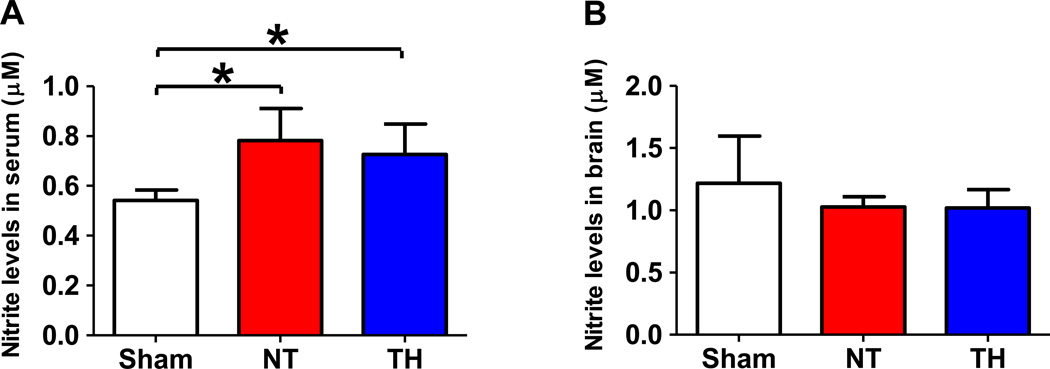

To elucidate the role of NOS3 in the beneficial effects of TH, we examined expression levels of total and phosphorylated NOS3 and VASP, a downstream target of PKG, in the brain tissue of mice. Although CA/CPR did not affect the total NOS3 expression, TH markedly increased the expression of phosphorylated NOS3 at Ser1177 in the brain compared to sham operated control mice and mice subjected to CA/CPR and maintained at normothermia (fig. 2A). On the other hand, TH decreased the expression of phosphorylated NOS3 at Thr495 compared to sham control (fig. 2B). Since phosphorylation at Ser1177 activates whereas phosphorylation at Thr495 inhibits NOS3, these observations suggest that TH activates NOS3 in the brain after CA/CPR. We also found that TH increased phosphorylated VASP at Ser239 compared to sham control and mice maintained at normothermia after CA/CPR corroborating the augmented NOS3 activity by TH after CA/CPR (fig. 2C). Cardiac arrest and CPR markedly increased the expression of phosphorylated Akt at Ser473 regardless of the temperature control (fig. 2D). Abundance of NOS1, NOS2, phosphorylated Akt at Thr308, phosphorylated AMPKα at Thr172, and Hsp90 were not affected by CA/CPR and TH (fig. 2, E–I). Although nitrite levels in serum were increased 3 hours after CA/CPR, TH did not affect the serum nitrite levels compared with normothermic control. Nitrite levels of brain homogenates were not affected by CA/CPR and TH (fig. 3, A and B).

Fig. 2.

Protein expression in brain cortex 3 hours after sham operation or cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CA/CPR). Sham, mice that were subjected to sham operation without CA/CPR. NT, mice that were maintained normothermia for 3 hours after CA/CPR. TH, mice that were treated with TH for 3 hours after CA/CPR. (A) Relative phosphorylated NOS3 at Ser1177 levels were quantified by dividing the phosphorylated at NOS3 at Ser1177 immunoreactivity by NOS3 immunoreactivity and normalized to values of sham-operated mice. (B) Relative phosphorylated NOS3 at Thr495 levels were quantified by dividing the phosphorylated NOS3 at Thr495 immunoreactivity by NOS3 immunoreactivity and normalized to values of sham-operated mice. (C) Relative phosphorylated VASP at Ser239 levels were quantified by dividing the phosphorylated VASP at Ser239 immunoreactivity by VASP immunoreactivity and normalized to values of sham-operated mice. (D) Relative phosphorylated Akt at Ser473 levels were quantified by dividing the phosphorylated Akt at Ser473 immunoreactivity by Akt immunoreactivity and normalized to values of sham-operated mice. (E) Relative NOS1 levels were quantified by dividing the NOS1 immunoreactivity by β-tubulin immunoreactivity and normalized to values of sham-operated mice. (F) Relative NOS2 levels were quantified by dividing the NOS2 immunoreactivity by β-tubulin immunoreactivity and normalized to values of sham-operated mice. (G) Relative phosphorylated Akt at Thr308 levels were quantified by dividing the phosphorylated Akt at Thr308 immunoreactivity by Akt immunoreactivity and normalized to values of sham-operated mice. (H) Relative phosphorylated AMPKα at Thr172 levels were quantified by dividing the phosphorylated AMPKα at Thr172 immunoreactivity by AMPKα immunoreactivity and normalized to values of sham-operated mice. (I) Relative Hsp90 levels were quantified by dividing the Hsp90 immunoreactivity by β-tubulin immunoreactivity and normalized to values of sham-operated mice. Representative blots are shown of 6 blots in each group. N=6–7. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, and ***P<0.001. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni post hoc test.

Fig. 3.

Nitrite concentrations in serum and brain homogenates 3 hours after sham operation or cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CA/CPR). Sham, mice that were subjected to sham operation. NT, mice that were maintained normothermia for 3 hours after CA/CPR. TH, mice that were treated with TH for 3 hours after CA/CPR. *P<0.05. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni post hoc test.

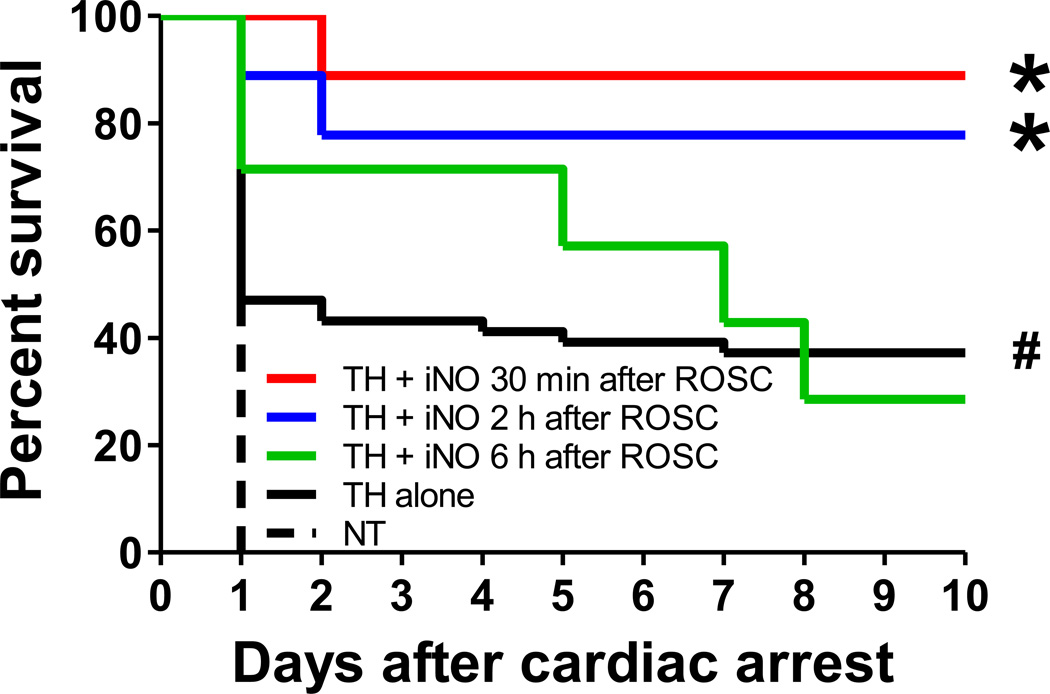

Survival after CA/CPR is better in mice treated with the combination of inhaled nitric oxide and TH than in mice treated with TH alone

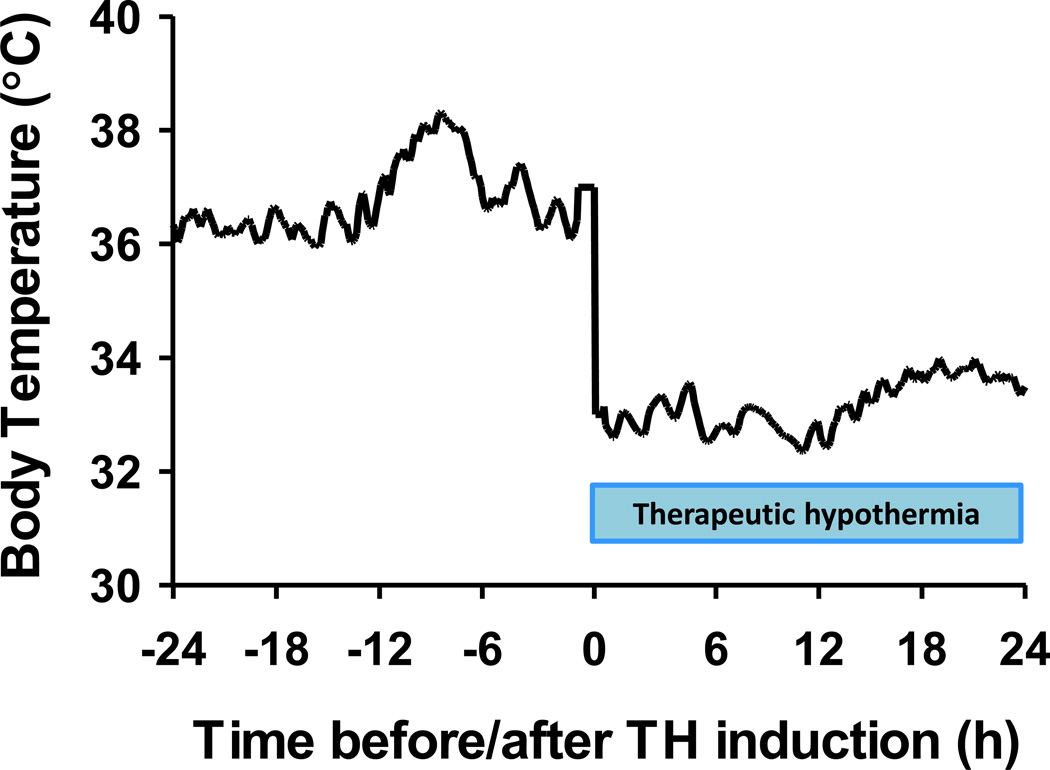

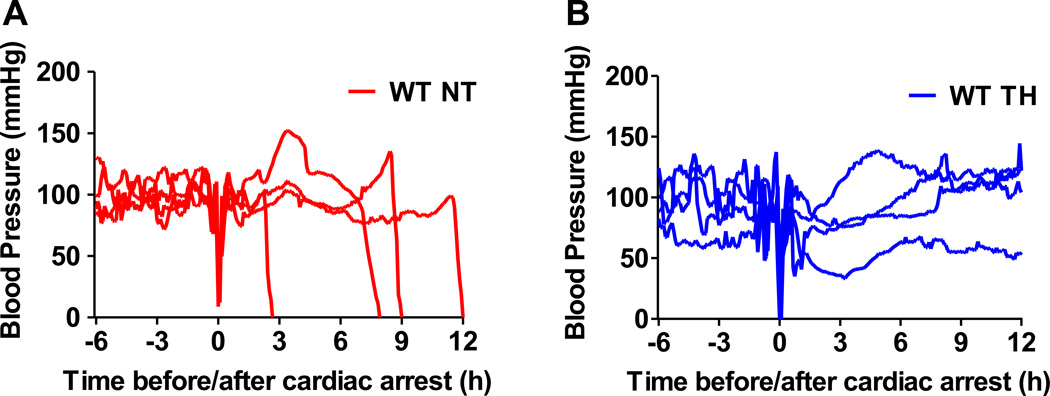

To determine whether or not inhaled nitric oxide improves outcomes after CA/CPR in normal mice treated with TH, we examined the effects of nitric oxide inhalation at 10, 20, 40, 60 and 80 ppm in WT mice treated with TH. To mimic the clinical care of CA patients more accurately, we developed a new protocol that includes a mechanical chest compression device and targeted temperature control (fig. 4, see Protocol 2 in Methods section). When maintained at normothermia (37°C) for the first 24 hours after 8 minutes of CA and CPR, 100% of WT mice died within 24 hours. TH initiated at 30 minutes after ROSC markedly improved survival rate of WT mice (fig. 5). Blood pressure after ROSC did not differ between surviving mice maintained at normothermia or treated with TH (fig. 6, A and B). Inhalation of nitric oxide at 40 or 60 (data not shown) ppm starting at 30 minutes after ROSC and continued for 24 hours further improved the survival rate after CA/CPR in mice treated with TH. While breathing nitric oxide at 10, 20, and 80 ppm tended to improve the survival rate in TH-treated mice, inhaled nitric oxide failed to provide statistically significant improvement in survival rate compared to TH alone at these doses (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Average body temperature of 4 WT mice before and after therapeutic hypothermia (TH) induction. Body temperature was recorded by a radiotelemetry device.

Fig. 5.

Survival rate during the first 10 days after cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CA/CPR). TH + iNO 30 min after ROSC, WT mice that were subjected to CA/CPR and treated with therapeutic hypothermia (TH) combined with inhaled NO at 40 ppm starting 30 minutes after ROSC. TH + iNO 2 h after ROSC, WT mice that were subjected to CA/CPR and treated with TH combined with inhaled NO at 40 ppm starting 2 hours after ROSC. TH + iNO 6 h after ROSC, WT mice that were subjected to CA/CPR and treated with TH combined with inhaled NO at 40 ppm starting 6 hours after ROSC. TH alone, WT mice that were treated with TH after CA/CPR. NT, WT mice that were maintained at normothermia for 24 hours after CA/CPR. N=9, 9, 7, 51, and 5 respectively. *P<0.05 vs TH alone. #P<0.05 vs NT. Differences in survival rates were analyzed with log-rank test.

Fig. 6.

Blood pressure before and after cardiac arrest. (A) WT NT, WT mice that maintained at normothermia for 24 hours after CA/CPR. N=4. (B) WT TH, WT mice that were treated with therapeutic hypothermia after CA/CPR. N=4. Blood pressure was recorded by a radiotelemetry device.

Inhaled nitric oxide remains beneficial during TH when initiated up to 2 hours after CA/CPR

To determine the window of opportunity during which inhaled nitric oxide is able to improve outcomes after CA/CPR in TH-treated mice, we examined the effects of nitric oxide inhalation starting 2 or 6 hours after ROSC on the survival rate after CA/CPR. Nitric oxide inhalation at 40 ppm starting up to 2 hours after ROSC improved the survival rate after CA/CPR (fig. 5). However, initiation of nitric oxide breathing 6 hours after ROSC failed to improve the survival rate in TH-treated mice.

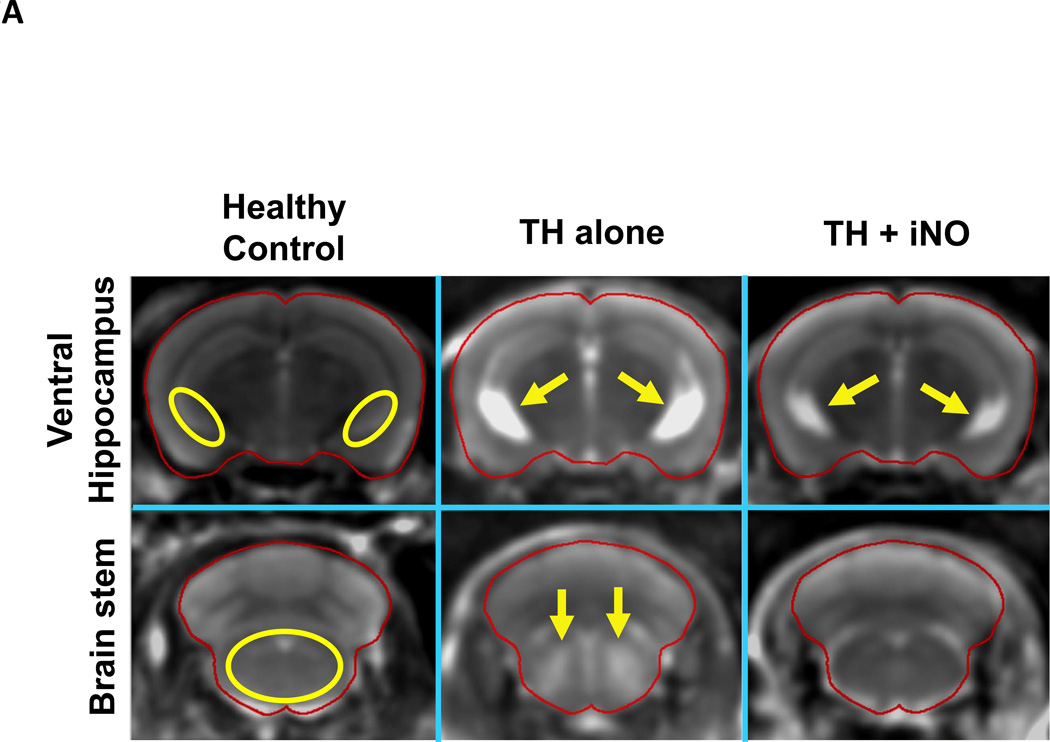

Inhaled nitric oxide prevents the brain injury after CA/CPR in TH-treated WT mice

TH confers neuroprotective effects after CA/CPR.5,6 To determine whether or not nitric oxide inhalation confers additional brain protection in mice treated with TH, we performed brain MRI 24 hours after CA/CPR in WT mice that were treated with TH alone or TH combined with inhaled nitric oxide at 40 ppm. T2-weighted images revealed that the brains of mice treated with TH alone exhibited hyperintense signal areas suggesting the development of vasogenic edema (fig. 7A). Breathing nitric oxide decreased the T2 intensity in the brain stem and ventral hippocampus of TH-treated WT mice (fig. 7, A and B). These results suggest that inhaled nitric oxide exerts brain protection above and beyond what is afforded by TH alone after CA/CPR.

Fig. 7.

(A) Representative brain T2 images of MRI in live mice at 24 hours after cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CA/CPR). Yellow circles indicate the region of interest containing the ventral hippocampus and brain stem. Yellow arrows indicate hyperintense signal areas. TH alone, mice that were treated with therapeutic hypothermia (TH) after CA/CPR. TH + iNO, mice that were treated with TH combined with inhaled NO at 40 ppm starting at 30 minutes after ROSC and continued for 24 hours. (B) Averaged T2 value in ventral hippocampus and brain stem. N=7 in each group. *P<0.05. Data were analyzed using unpaired t-test.

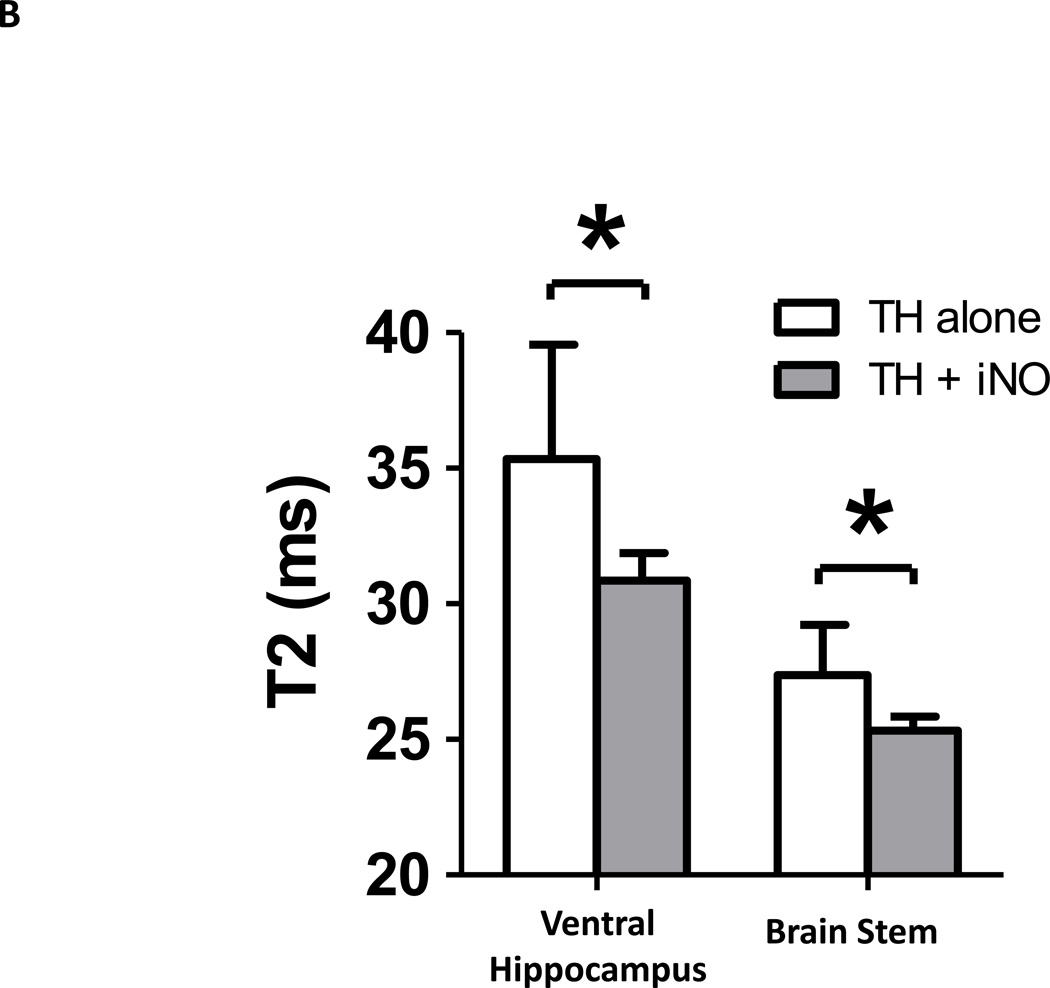

Inhaled nitric oxide does not increase the cerebral blood flow after CA/CPR

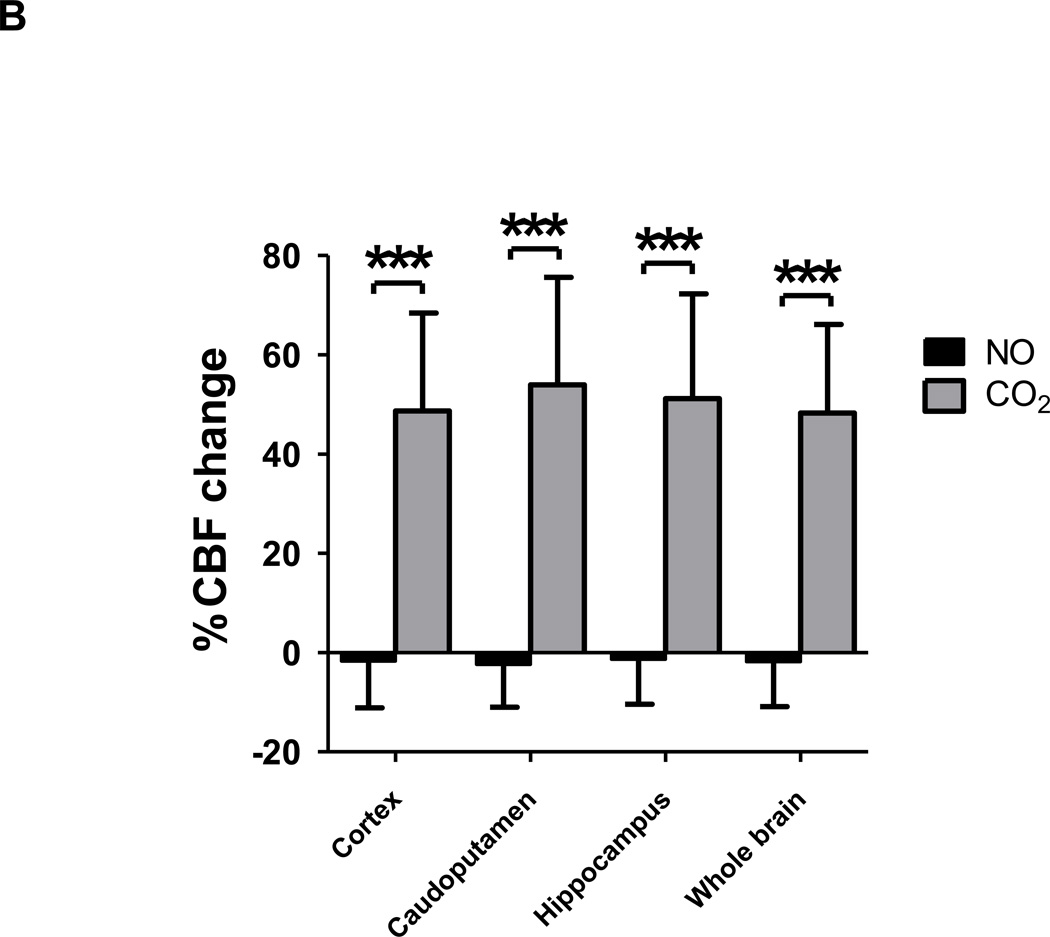

To characterize the mechanisms responsible for the neuroprotective effects of inhaled nitric oxide after CA/CPR, we measured CBF by continuous ASL technique with MRI in WT mice. ASL demonstrated that breathing nitric oxide gas at 40 ppm mixed with air did not increase CBF after CA/CPR in any regions in the brain during hypothermia (~33°C). In contrast, inhalation of 7% CO2 with 21% oxygen markedly increased CBF after CA/CPR in cortex, caudoputamen, hippocampus, and whole brain (fig. 8, A and B). These results suggest that nitric oxide inhalation does not exert its beneficial effects after CA/CPR by increasing CBF.

Fig. 8.

(A) Time-series of averaged % cerebral blood flow (CBF) change relative to the baseline after cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CA/CPR). CBF was measured by continuous arterial spin labeling (ASL) in cortex, caudoputamen, hippocampus, and whole brain. Gray shaded areas indicate inhalation of either 40 ppm NO mixed with air or 7% CO2 with 21% oxygen. N= 6. (B) Averaged % CBF change relative to the baseline after CA/CPR in response to the inhalation of NO and CO2. N=6. ***P<0.001 vs NO and baseline. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni post hoc test.

Discussion

Potential role of nitric oxide-dependent signaling in the beneficial effects of hypothermia have been suggested previously.20 Along these lines, we previously reported that short term (24 hours) survival rate of mice resuscitated from CA with intra-arrest cooling was markedly worsened by deficiency of NOS3 or sGCa1 in mice.10 By directly comparing the survival rates of WT and NOS3−/− mice maintained at normothermia or treated with hypothermia after resuscitation from CA, the current results extended these findings and revealed that NOS3 is required for the protective effect of hypothermia in a mouse model of CA/CPR. The critical role of NOS3 in the salutary effects of TH is further supported by the observation that beneficial effects of TH in WT mice resuscitated from CA were associated with activation of NOS3 and phosphorylation of VASP in the brain. Taken together, our observations suggest that beneficial effects of TH are mediated via the NOS3-cGMP-dependent signaling mechanisms after cardiac arrest and CPR.

Since hypothermia failed to improve the survival rate in NOS3−/− mice, we examined whether or not replacement of nitric oxide by nitric oxide inhalation could improve outcomes after CA/CPR in hypothermia-treated NOS3−/− mice. We observed that breathing nitric oxide at 40 ppm for 48 hours, but not 24 hours, markedly improved the survival rate in NOS3−/− mice compared to NOS3−/− mice treated with or without hypothermia. These results suggest that nitric oxide inhalation improves outcomes after CA/CPR in NOS3−/− mice in which hypothermia alone is insufficient to improve survival rates. If these observations are extrapolated to human beings, nitric oxide inhalation combined with hypothermia may be able to improve outcomes after CA/CPR in patients in whom TH alone is ineffective due to the impaired ability to produce nitric oxide (e.g., endothelial dysfunction). Further studies are warranted to examine effects of nitric oxide inhalation on outcomes after CA/CPR in mouse models of endothelial dysfunction (e.g., mice with diabetes mellitus or obesity).

To determine the effects of nitric oxide inhalation in WT mice resuscitated from CA and treated with targeted hypothermia of 33°C, we modified our experimental protocol. Since TH alone markedly improved survival rate of WT mice subjected to 7.5 minutes of CA (e.g., greater than 90% at 10 days after CA), we prolonged the arrest time to 8 minutes in the new protocol (see Protocol 2 in the Method section). We also developed and used a novel mechanical mouse CPR device in the new protocol to increase the consistency of chest compression across multiple experimental groups. All normothermic control mice maintained at 37°C died within 24 hours after subjected to 8 minutes of CA. Therapeutic hypothermia at 33°C markedly improved the survival rate of WT mice to approximately 40% at 10 days after CA. Using this robust protocol, we observed that nitric oxide breathing at 40 or 60 ppm markedly improved outcomes after CA/CPR in TH-treated mice above and beyond TH alone.

While nitric oxide inhalation at 10, 20, and 80 ppm failed to improve the survival rate after CA/CPR in mice treated with TH, inhaled nitric oxide did not impair the beneficial effects of TH at any concentrations. The reason why some concentrations of inhaled nitric oxide exerted additional beneficial effects above and beyond TH, whereas higher and lower concentrations did not, is unclear. Absence or attenuation of the beneficial effects of inhaled nitric oxide at 80 ppm on ischemic brain injury appears to be consistent with previous studies in stroke models. For example, Li and colleagues reported that inhaled nitric oxide at 10, 20, 40 and 60 ppm, but not at 80 ppm, reduced the infarct volume in adult mice subjected to middle cerebral artery occlusion and reperfusion.21 Charriaut-Marlangue and colleagues reported that breathing nitric oxide at 20 ppm during ischemia, but not 5 or 80 ppm, reduced the infarct volume in a model of neonatal rat brain ischemia.22 It is of note that breathing 80 ppm nitric oxide during ischemia increases nitrotyrosine-positive neurons in cortex of newborn rats compared to rats that breathed air in the latter study. It is possible that breathing high concentration of nitric oxide may increase production of injurious peroxynitrite during I/R when the production of reactive oxygen species is also increased.

We observed that initiating nitric oxide inhalation 30 minutes or 2 hours, but not 6 hours, after ROSC markedly improved the survival rates in mice that were treated with TH. There was no difference between the survival rates of mice that breathed nitric oxide starting 30 minutes and 2 hours after ROSC. These results suggest that there is a therapeutic window after which the benefit of inhaled nitric oxide on survival after CA/CPR is lost. We found this therapeutic window for inhaled nitric oxide to close between 2 and 6 hours after ROSC in our mouse model. Although the therapeutic window in humans remains to be determined, our results suggest that nitric oxide inhalation can improve neurological outcomes after CA/CPR, even if it is initiated several hours after ROSC. The implication of these observations for clinical implementation of inhaled nitric oxide after CA/CPR is significant because our results suggest that inhaled nitric oxide can be started after patients are transported to the hospital, and informed consent is obtained.

In previous studies, inhaled nitric oxide has been shown to cause cerebral vasodilation during brain ischemia in rodents and sheep.23 To determine whether or not the beneficial effects of nitric oxide inhalation after CA/CPR are associated with augmentation of cerebral perfusion, we measured whole brain CBF by ASL technique. Surprisingly, nitric oxide inhalation starting 1 hour after CPR during hypothermia failed to alter CBF in mice. In contrast, inhalation of 7% CO2 robustly increased CBF in WT mice 1 hour after CA/CPR. These observations suggest that vasoreactivity of cerebral vessels are intact after CA/CPR and that the ASL technique used in our study has sufficient sensitivity to detect changes in CBF in mice. The reasons why our findings differ from those of Terpolilli et al. are likely multifactorial and include differences in the models studied and methods used to assess CBF. Nonetheless, our results do not support the hypothesis that nitric oxide inhalation improves outcomes after CA/CPR by increasing cerebral perfusion.

Although we observed that serum nitrite levels were markedly elevated at 3 hours after CPR, TH did not further increase serum nitrite levels compared to normothermia. In addition, brain nitrite levels were not affected by CA/CPR or TH. Although these results appear to conflict with the apparent activation of NOS3 in the brain, tissue and blood nitrite levels are regulated not only by NOS activity but multiple factors including enzymatic and nonenzymatic reduction of nitrite/nitrate to nitric oxide, and nitrite and nitrate levels in diet.24 Further, NOS3 is more concentrated in CA1 hippocampal pyramidal neurons than in any other brain areas.25 It is conceivable that TH may augment nitric oxide levels in selected regions of the brain without affecting global levels of nitrite.

A previous study suggested the potential role of Akt-dependent signaling in the beneficial effects of TH after CA.26 Since Akt phosphorylates NOS3, we examined expression of phosphorylated Akt in the brain of WT mice resuscitated from CA/CPR. While CA/CPR markedly increased Akt phosphorylation at Ser473, no difference was detected between brains treated with normothermia or hypothermia. Levels of phosphorylated Akt at Thr308, phosphorylated AMPKα at Thr172, Hsp90 were not affected by CA/CPR or TH, suggesting that phosphorylation of NOS3 were augmented via other mechanisms during TH. Mechanisms responsible for the TH-induced NOS3 phosphorylation remains to be determined in the future studies.

In summary, the present study revealed that nitric oxide breathing remains beneficial in TH-treated mice. Our observations also suggest that NOS3-derived nitric oxide is required for the beneficial effects of TH to improve outcomes after CA/CPR. Since endothelial dysfunction is associated with reduced vascular nitric oxide bioavailability, our findings in mice that are genetically deficient in vascular nitric oxide synthesis (NOS3−/− mice) raises the possibility that patient with endothelial dysfunction (due a broad spectrum of cardiovascular disorders) may be less likely to benefit from TH after CA/CPR. Lastly, our current results suggest an exciting possibility that nitric oxide breathing may improve outcomes after CA/CPR in patients in whom TH alone is ineffective due to impaired endogenous nitric oxide production.

What we know about the topic.

Inhaled nitric oxide (NO) and therapeutic hypothermia have previously been shown to improve survival in mice after cardiac arrest and CPR; however, the mechanism of protection during hypothermia is unknown.

What this study tells us that is new

Endothelial NO synthase derived NO is required for protection by therapeutic hypothermia after CPR; but inhaled NO remains beneficial even during therapeutic hypothermia. These results suggest that inhaled NO may be beneficial after CPR during disease states characterized by impaired NO bioavailability.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING SOURCES: This work was supported by postdoctoral fellowships from the American Heart Association’s Founders Affiliate and from the Massachusetts General Hospital Tosteson Fund for Medical Discovery to KK, R01 grants from the NHLBI (HL101930 to FI and HL110378 to FI and KB), a network grant from the Foundation LeDucq to KB, and a sponsored research agreement from IKARIA Inc. to FI.

Reference List

- 1.Field JM, Hazinski MF, Sayre MR, Chameides L, Schexnayder SM, Hemphill R, Samson RA, Kattwinkel J, Berg RA, Bhanji F, Cave DM, Jauch EC, Kudenchuk PJ, Neumar RW, Peberdy MA, Perlman JM, Sinz E, Travers AH, Berg MD, Billi JE, Eigel B, Hickey RW, Kleinman ME, Link MS, Morrison LJ, O'Connor RE, Shuster M, Callaway CW, Cucchiara B, Ferguson JD, Rea TD, Vanden Hoek TL. Part 1: Executive Summary: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2010;122:S640–S656. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.970889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WRITING GROUP. Roger VrL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, Bravata DM, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Makuc DM, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, Moy CS, Mozaffarian D, Mussolino ME, Nichol G, Paynter NP, Soliman EZ, Sorlie PD, Sotoodehnia N, Turan TN, Virani SS, Wong ND, Woo D, Turner MB. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2012 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125:e2–e220. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823ac046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roine RO, Kajaste S, Kaste M. Neuropsychological sequelae of cardiac arrest. JAMA. 1993;269:237–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laver S, Farrow C, Turner D, Nolan J. Mode of death after admission to an intensive care unit following cardiac arrest. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:2126–2128. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2425-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mild Therapeutic Hypothermia to Improve the Neurologic Outcome after Cardiac Arrest. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:549–556. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernard SA, Gray TW, Buist MD, Jones BM, Silvester W, Gutteridge G, Smith K. Treatment of Comatose Survivors of Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest with Induced Hypothermia. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:557–563. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa003289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bloch KD, Ichinose F, Roberts JD, Zapol WM. Inhaled NO as a therapeutic agent. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;75:339–348. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang Z, Huang PL, Ma J, Meng W, Ayata C, Fishman MC, Moskowitz MA. Enlarged Infarcts in Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase Knockout Mice Are Attenuated by Nitro-l-Arginine. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1996;16:981–987. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199609000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones SP, Girod WG, Palazzo AJ, Granger DN, Grisham MB, Jourd'Heuil D, Huang PL, Lefer DJ. Myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury is exacerbated in absence of endothelial cell nitric oxide synthase. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1999;276:H1567–H1573. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.5.H1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nishida T, Yu JD, Minamishima S, Sips PY, Searles RJ, Buys ES, Janssens S, Brouckaert P, Bloch KD, Ichinose F. Protective effects of nitric oxide synthase 3 and soluble guanylate cyclase on the outcome of cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation in mice. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:256–262. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318192face. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hataishi R, Rodrigues AC, Neilan TG, Morgan JG, Buys E, Sruti S, Tambouret R, Jassal DS, Raher MJ, Furutani E, Ichinose F, Gladwin MT, Rosenzweig A, Zapol WM, Picard MH, Bloch KD, Scherrer-Crosbie M. Inhaled Nitric Oxide Decreases Infarction Size and Improves Left Ventricular Function in a Murine Model of Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H379–H384. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01172.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu X, Huang Y, Pokreisz P, Vermeersch P, Marsboom G, Swinnen M, Verbeken E, Santos J, Pellens M, Gillijns H, Van de WF, Bloch KD, Janssens S. Nitric oxide inhalation improves microvascular flow and decreases infarction size after myocardial ischemia and reperfusion. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:808–817. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lang JD, Jr, Teng X, Chumley P, Crawford JH, Isbell TS, Chacko BK, Liu Y, Jhala N, Crowe DR, Smith AB, Cross RC, Frenette L, Kelley EE, Wilhite DW, Hall CR, Page GP, Fallon MB, Bynon JS, Eckhoff DE, Patel RP. Inhaled NO accelerates restoration of liver function in adults following orthotopic liver transplantation. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2583–2591. doi: 10.1172/JCI31892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Minamishima S, Kida K, Tokuda K, Wang H, Sips PY, Kosugi S, Mandeville JB, Buys ES, Brouckaert P, Liu PK, Liu CH, Bloch KD, Ichinose F. Inhaled Nitric Oxide Improves Outcomes After Successful Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation in Mice. Circulation. 2011;124:1645–1653. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.025395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kida K, Minamishima S, Wang H, Ren J, Yigitkanli K, Nozari A, Mandeville JB, Liu PK, Liu CH, Ichinose F. Sodium sulfide prevents water diffusion abnormality in the brain and improves long term outcome after cardiac arrest in mice. Resuscitation. 2012;83:1292–1297. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Minamishima S, Bougaki M, Sips PY, De Yu J, Minamishima YA, Elrod JW, Lefer DJ, Bloch KD, Ichinose F. Hydrogen Sulfide Improves Survival After Cardiac Arrest and Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation via a Nitric Oxide Synthase 3-Dependent Mechanism in Mice. Circulation. 2009;120:888–896. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.833491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacArthur PH, Shiva S, Gladwin MT. Measurement of circulating nitrite and S-nitrosothiols by reductive chemiluminescence. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2007;851:93–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zaharchuk G, Mandeville JB, Bogdanov AA, Weissleder R, Rosen BR, Marota JJA. Cerebrovascular Dynamics of Autoregulation and Hypoperfusion: An MRI Study of CBF and Changes in Total and Microvascular Cerebral Blood Volume During Hemorrhagic Hypotension. Stroke. 1999;30:2197–2205. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.10.2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spano VR, Mandell DM, Poublanc J, Sam K, Battisti-Charbonney A, Pucci O, Han JS, Crawley AP, Fisher JA, Mikulis DJ. CO2 Blood Oxygen Level-dependent MR Mapping of Cerebrovascular Reserve in a Clinical Population: Safety, Tolerability, and Technical Feasibility. Radiology. 2013;266:592–598. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12112795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang L, Kumar S, Kaminski A, Kasch C, Sponholz C, Stamm C, Ladilov Y, Steinhoff G. Importance of endothelial nitric oxide synthase for the hypothermic protection of lungs against ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Thorac Cardiovas Surg. 2006;131:969–974. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li YS, Shemmer B, Stone E, Nardi A, Jonas S, Quartermain D. Neuroprotection by inhaled nitric oxide in a murine stroke model is concentration and duration dependent. Brain Res. 2013;1507:134–145. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Charriaut-Marlangue C, Bonnin P, Gharib A, Leger PL, Villapol S, Pocard M, Gressens P, Renolleau S, Baud O. Inhaled Nitric Oxide Reduces Brain Damage by Collateral Recruitment in a Neonatal Stroke Model. Stroke. 2012;43:3078–3084. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.664243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Terpolilli NA, Kim SW, Thal SC, Kataoka H, Zeisig V, Nitzsche B, Klaesner B, Zhu C, Schwarzmaier S, Meissner L, Mamrak U, Engel DC, Drzezga A, Patel RP, Blomgren K, Barthel H, Boltze J, Kuebler WM, Plesnila N. Inhalation of Nitric Oxide Prevents Ischemic Brain Damage in Experimental Stroke by Selective Dilatation of Collateral Arterioles. Circ Res. 2012;110:727–738. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.253419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park JW, Piknova B, Huang PL, Noguchi CT, Schechter AN. Effect of Blood Nitrite and Nitrate Levels on Murine Platelet Function. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55699. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dinerman JL, Dawson TM, Schell MJ, Snowman A, Snyder SH. Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase Localized to Hippocampal Pyramidal Cells: Implications for Synaptic Plasticity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:4214–4218. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.10.4214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beiser DG, Wojcik KR, Zhao D, Orbelyan GA, Hamann KJ, Vanden Hoek TL. Akt1 genetic deficiency limits hypothermia cardioprotection following murine cardiac arrest. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298:H1761–H1768. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00187.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]