Abstract

Objective. To develop and implement a capstone course that would allow students to reflect on their development as a professional, assess and share their achievement of the college’s outcomes, complete a professional portfolio, establish a continuing professional development plan, and prepare to enter the pharmacy profession.

Design. Students were required to complete a hybrid course built around 4 online and inclass projects during the final semester of the curriculum.

Assessment. Faculty used direct measures of learning, such as reading student portfolios and program outcome reflections, evaluating professional development plans, and directly observing each student in a video presentation. All projects were evaluated using standardized rubrics. Since 2012, all graduating students met the course’s minimum performance requirements.

Conclusion. The course provided an opportunity for student-based summative evaluation, direct observation of student skills, and documentation of outcome completion as a means of evaluating readiness to enter the profession.

Keywords: capstone, assessment, pharmacy academia, continuing professional development

INTRODUCTION

Capstones are the top facing stones of a structure. They are more than decorative, however; they shield a finished structure by protecting the mortar in the joints below. Metaphorically, capstones represent a crowning achievement, or the culmination, of a complex effort.1 Curricular capstone courses leverage both connotations to provide an intentional, carefully constructed “binding agent” at the key degree program transition point: the movement between formal coursework and self-directed learning following formal studies. As such, capstone courses are obvious tools to achieve learning goals articulated for pharmacy education.2 Achieving these goals enables practitioners to manage a multi-decade career arch within complex, changing practice realities.3-4

Capstone courses scheduled as the final instructional activity in doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) curricula are not prevalent.2 Yet, this placement solves challenges facing pharmacy faculty members such as documenting achievement of curriculum learning goals, including students in meaningful learning/achievement assessment, providing proof of educational effectiveness of a program, supporting institutional assessment efforts, and reinforcing the bond between graduating students and the program. The article describes one institution’s integrative/reflective capstone course and shares details of that course’s structure and outcomes.

Terminal capstone courses are embedded across the US post-secondary academic landscape.5 Graduate programs have long labeled these capstone courses “thesis/dissertation development and defense.” As the final act of a master’s or doctoral student, these courses require a public demonstration of the candidate’s academic accomplishment and an ability to communicate awareness of this accomplishment to professional peers. The type, location, and level of institutional integration among undergraduate senior capstone courses have multiplied since the 1970s.5 Capstone courses are an increasingly common part of undergraduate life.6 Typically, these capstone courses review program goals, lead students through a structured reflection process (to understand and articulate the totality of each student’s learning, including general education: academic major connections, integration and synthesis within the major, meaningful, major-career experience connections), shift these near-graduates’ self-identity from faculty-dependent learner to self-managed learner, and forecast what they have learned across their future.6

In this article, we refer to this course outcome model as an “integrative/reflective capstone” course. Despite their proven worth, end-of-program, integrative/reflective capstone courses are rare within professional health care programs, particularly in pharmacy education. In January 2014, a survey of school/college web content was conducted of 136 AACP member institutions’ curricula for their PharmD programs (ie, posted curricula grids, catalog descriptions, and, when needed, course syllabi). Of these programs, only 6 offered a course at the end of the PharmD curriculum that embodied clear integrative/reflective capstone course outcome goals. Twenty-seven programs placed a non-experiential course in the final program year, but these courses fell into 1 of 4 categories: advanced pharmacy practice experiences (APPE) preparation; student presentation; grand rounds/therapeutics review; or licensure test preparation. Another 7 institutions placed a “capstone” course at the end of year 3, with a quarter of the curriculum left to complete afterwards.

The absence of integrative/reflective capstone courses in pharmacy education is surprising considering the maturing of pharmacy’s guiding educational purposes and processes. Publications of American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy’s (AACP) Argus Commission and the Commission to Implement Change in Pharmaceutical Education from as early as the late 1980s and early 1990s mark the turn in pharmacy education from “trade” to “professional.”7-9 The Argus Commission shaped the contemporary entry-level PharmD degree contours by delineating ability outcomes and competencies that supported professional practice in complex, multi-disciplinary health care systems.8-9 Agreement was strong that critical-thinking (analytic/problem-solving), rhetorical (oral and written), interpersonal, quantitative, intercultural, and professional/ethical abilities were obvious outcomes for professional sustainability moving forward. This emphasis was initially described under the heading “liberalizing the profession.”9 Equally acknowledged was the need for pharmacy education, as with all professional education, to develop students’ ability to reflect on their experiences, their learning, and their on-going professional needs.10 The founding faculty members of the Belmont University College of Pharmacy (BUCOP) had been profoundly affected by this pioneering work and had thought for years about how to achieve these curricular outcomes. They saw tight alignment between the educational goals of interactive/reflective capstone courses and the higher-order learning needed for pharmacy practice. The 2011-2012 Argus Commission report, which advocated for the introduction of capstone courses in PharmD curricula, reinforced the college’s belief that its integrated/reflective capstone course was on the forefront of best educational practice.11

These efforts propelled pharmacy education from a technical to a professional curriculum. Instead of a linear, content-coverage model, pharmacy academy consensus (reflected in revised accreditation standards4) pressed for curricula that treated professional knowledge, skill, and attitudinal development as equal components. Additionally, there was an expectation that this student growth would be developed via intentional and assessed mechanisms, resulting in noticeable differences in students.

In 2007 Belmont University developed a PharmD program honoring the university’s defining academic mandate by including a terminal capstone course.12 Thus, a capstone course was created and offered in the eighth semester of the PharmD program. It has been taught to the college’s graduating classes since 2012.

The capstone is a 1-credit graduate course that all PharmD students take in the spring semester of fourth curricular year. The course was designed and initially taught by 2 founding faculty members of the college, whose efforts were guided by 2 currents of thought. The course’s structure, goals, and projects were influenced by the work of Schön, Bloom et al, Bonwell and Eison, and the Commission to Implement Change in Pharmaceutical Education.7,10,13,14 The course strives to develop students’ abilities to engage in “reflection-in-action” (Schön); higher-order “evaluative thinking” (Bloom et al); and “active learning” as a key to sophisticated abilities development (Bonwell and Eison).

Equally influential on the course was the Belmont University commitment to a liberal arts education, and the story of Janus, the 2-headed god of Roman mythology. The course reflects the university’s institutional belief, articulated by former Belmont University Provost, Dr. Marsha McDonald, that “… A capstone course enables the student to synthesize the wide array of curricular and cocurricular learning that has been a part of his/her program of study and to prepare to use that learning in a meaningful way as he/she begins a career and a lifetime of learning.”12 From Roman mythology’s Janus, the course borrows the awareness that one must look backward and forward to understand the present.15

Through a semester-long mix of online and in-person activity, course faculty members coached students through a structured review/analysis of their entire professional training and discussed students’ readiness to enter professional practice. Course activities prompted students to examine the “big picture” from the perspective of having finished the first formal portion of professional training (ie, the PharmD curriculum) and to develop plans for the next portion of their professional development, self-managed practice.

DESIGN

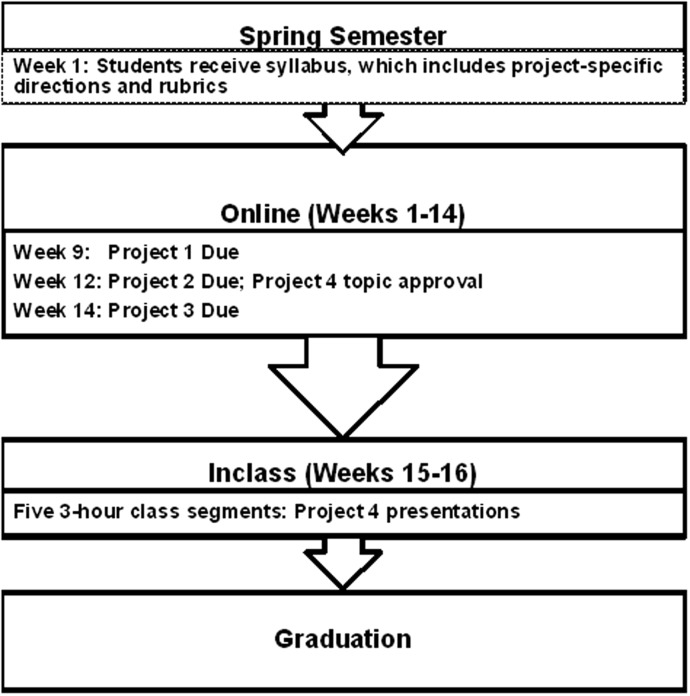

The PharmD capstone course included a 14-week online component followed by a 2-week in-person component, scheduled for the 2 weeks immediately preceding graduation (Figure 1). Students communicated with the course instructor(s) and submitted projects via e-mail during the online portion. To retain the reflection-focused course goals, the instructors’ roles were defined as coach or evaluator. No new content was built into the course because at this point in the students’ careers, new material would be selected by the student. Rather, the course allowed students to demonstrate their ability to perform at levels commensurate with entry-level professional practice in the following areas: critical thinking, self-assessment, written and oral communication, self-directed learning, and professionalism.

Figure 1.

The PharmD capstone course (PHM 6365) structure at Belmont University's College of Pharmacy

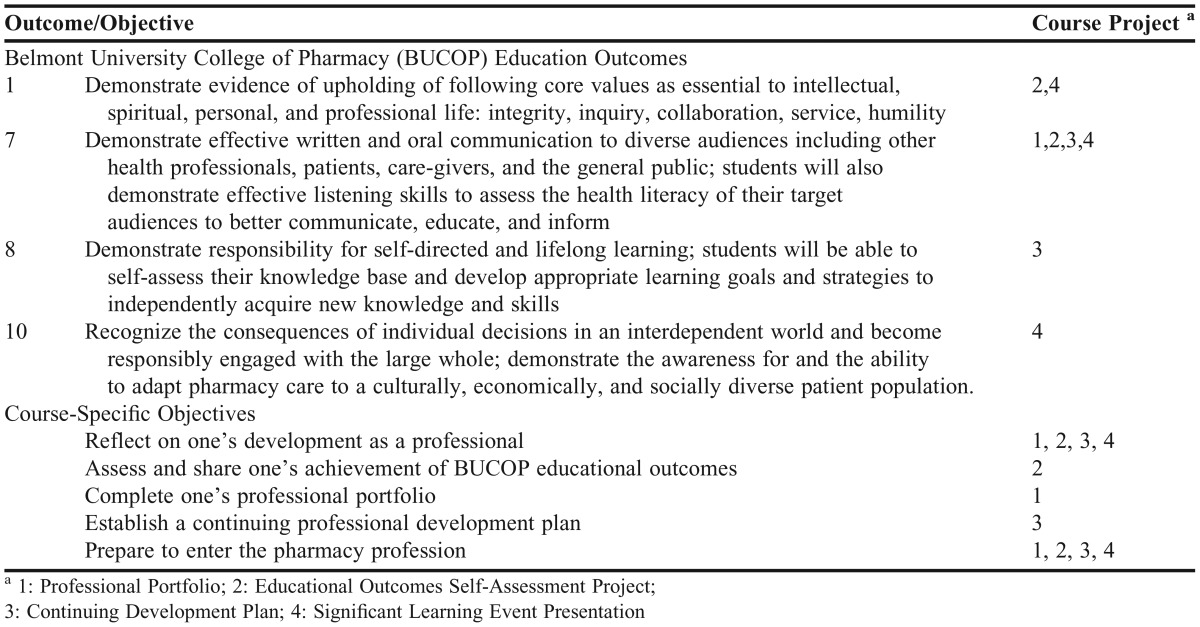

The capstone course was structured around 4 projects that turned students’ analytic/evaluative attention to 3 specific times in their professional development: the past (where they had been and what they had learned in the past 4 years); the present (where/who they were on the cusp of graduation); the future (where did they want to go; how would they get there). Each project was designed to enable students to demonstrate completion of course-specific objectives and mastery of select college curricular outcomes (Table 1). Each project resulted in an assessed, public artifact that confirmed students’ abilities and professional growth. Students received detailed instructions for each of the 4 projects at the start of the term, including performance criteria, grading rubrics (Appendix 1), available support, and due dates. There was no final examination, and the course used pass/fail grades.

Table 1.

Projects Used to Demonstrate Achievement of Learning Objectives for the PharmD Capstone Course

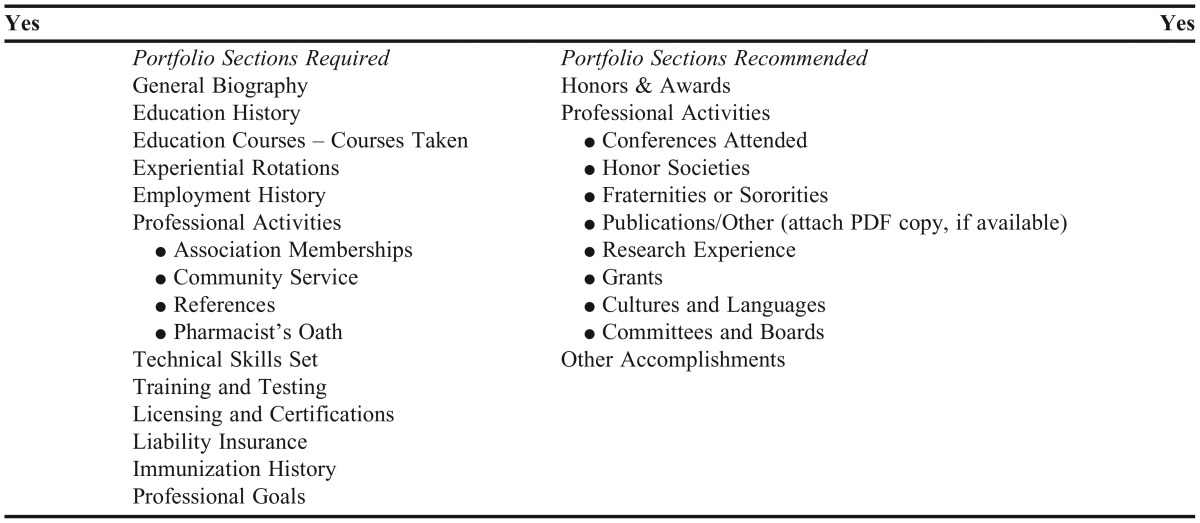

Project 1, the Professional Portfolio (“Looking Back and Recording the Journey”), required each student to complete an electronic portfolio (RxPortfolio, RXinsider, West Warwick, RI) they had established upon matriculation. The portfolio served as a living document that recorded development from student to independent practitioner. The project verified that each student’s portfolio was up-to-date, included all required portfolio elements prior to graduation, and offered students access to experienced faculty mentorship in selecting documentary artifacts to share with external audiences, such as potential employers and residency directors, and with internal audiences such as college and university assessment committees. Course instructors assessed the completed portfolios using a 3 performance-level rubric (excellent, acceptable, unacceptable) included in the project directions packet.

Project 2 was the BUCOP Educational Outcomes Self-Assessment (“Assessing Today”), which challenged students to produce a detailed, well-written, 6-12 page self-assessment of their achievement of the college’s 10 educational outcomes. For each outcome, students accounted for where they were at matriculation versus where they were at graduation. They linked that development to specific program-related elements that contributed to the growth they claimed had occurred. Because the self-assessment was 1 of 2 formal papers required at the end of curricular program, it provided an artifact to demonstrate each student’s ability to author professional-grade documents. Project 2 instructions included detailed performance criteria and a 3 performance-level grading rubric. Directions and project advice reinforced the expectation that a successful self-assessment document should demonstrate a writer’s ability to articulate and develop a focused, persuasive message that aligns with the task’s goals, identify strengths/weaknesses, articulate specific continued development options, and edit with accuracy. Each project was graded by course instructors using a project-specific grading tool, or rubric.

Project 3 documented the transition from student to professional (“Looking Back/Looking Forward”), which required students to prepare a Continuing Professional Development (CPD) plan using a 5-step process. Because the project presentation template included career goal definitions and a planning process developed by the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE), students were encouraged to complete ACPE’s 1-hour, online CPD presentation. Each student identified the accomplishments, experiences, training, achievements, etc., needed to become proficient in their current interest area. Using the SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and timed) outline, students developed a list of professional goals. Students then selected a classmate who identified a similar career direction and conducted a 30- to 45-minute focused discussion to assess and strengthen each other’s goals. Finally, students developed a written CPD plan that validated their goals and strategy for accomplishing these goals. This document was the second of 2 formal papers students produced prior to graduation. Each plan was evaluated by course instructors using the project’s 3 performance-level rubric and provided information useful to programmatic assessment.

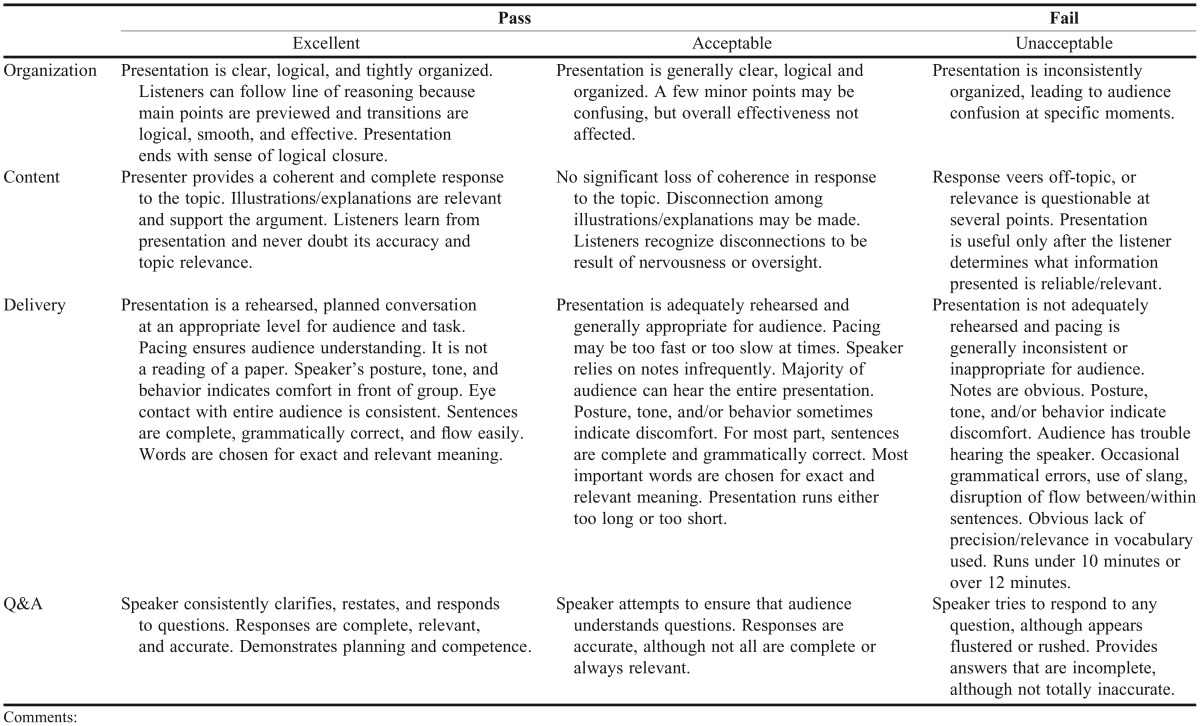

Project 4, the Significant Learning Event Presentation (“Sharing the Key”), served as the final, formal oral presentation students made in the PharmD curriculum. The topic was self-identified, within specific parameters, and approved by course instructors. Students reviewed their time in the program to identify a “significant learning event,” a singular moment that proved to be powerful in their pharmacy education. Students delivered an 8- to 10-minute speech with a 2-minute question session (ie, “podium presentation”) to a large audience of professional peers (classmates and faculty members). The presentations occurred on campus during weeks 15 and 16 of the spring semester. Speeches were evaluated using a standardized presentation evaluation rubric and were videotaped and archived so they could serve as retrievable learning artifacts.

The Belmont University Institutional Review Board determined that this study was exempt from review.

EVALUATION AND ASSESSMENT

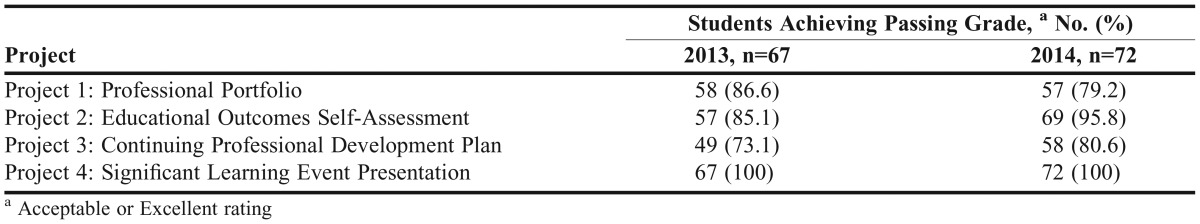

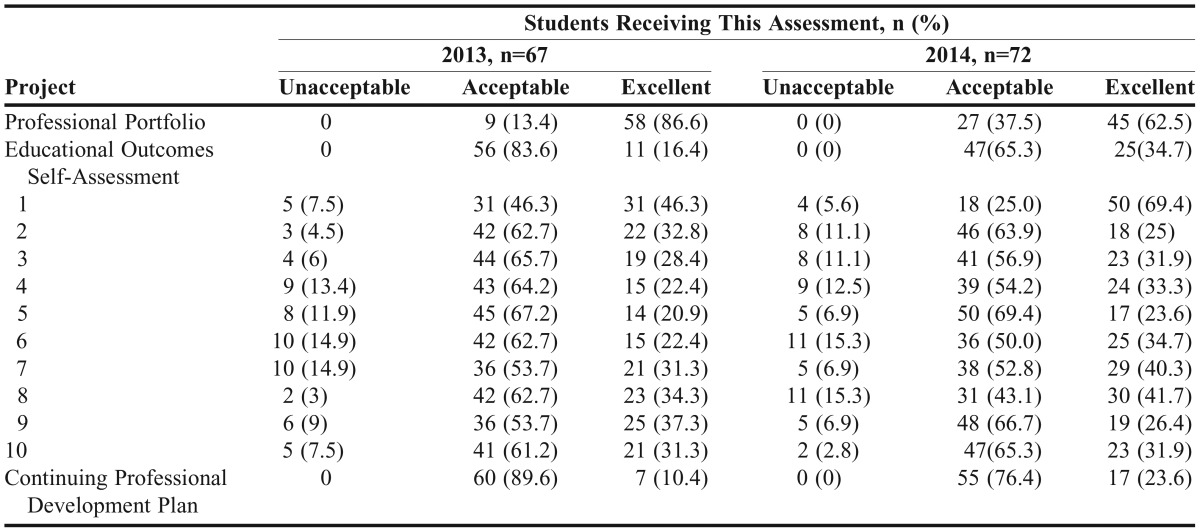

In the pilot offering of the course, data were not collected for pass rates or grades for each project. The data presented here reflects the activity of students enrolled in the capstone course during the second and third offerings in spring 2013 and spring 2014. At least 73% of enrolled students passed Projects 1, 2, and 4 on initial submission (Table 2). While course instructors scored most Projects 1 and 4 submissions “excellent,” “acceptable” was the most common score awarded for Projects 2 and 3. Instructors provided feedback to any student whose initial project submissions did not receive a passing grade. After consultation and revisions, students resubmitted projects for reevaluation; however, “acceptable” was the highest rating a resubmission could receive. All students passed each project by the third attempt. Table 3 shows the final assessment results for each project.

Table 2.

Student Achievement of Passing Grade on Initial Submission in the PharmD Capstone Course

Table 3.

Final Individual Student Assessment Results for Projects 1-3 in the PharmD Capstone Course

Projects 1, 3, and 4 took the least amount of time for faculty members to grade (5 minutes, 20 minutes, and 12 minutes per submission, respectively). Due to the amount of time required to grade Project 2 (30 minutes per submission), the 2 course instructors shared the responsibility of grading this assignment. The Cohen Kappa test was performed to assess the inter-rater agreement of the grades (excellent, acceptable, or unacceptable). Results verified that the instructors evaluated the student reflections equally.16,17 Kappa agreement was 68% for the 3 sets of observations measured, with kappa scores of 0.68 (substantial), 0.52 (moderate) and 0.65 (substantial). In the third offering, one instructor graded all the projects, and consistency was assumed to be intact since this instructor was involved with the course in all 3 offerings.

For Project 1, most students submitted portfolios that reflected well upon them as new members of the professional community. They showcased students excelling in service to others, leadership, completion of core courses and academic concentration electives, and documented their training and experiences for career mobility. Because the project focused on collecting relevant information using predetermined, restrictive presentation templates, it required the least higher-order thinking of the 4 course projects.

As intended by the course designers, Project 2 required students to engage in higher-order cognitive activity: they were required to reflect, make judgments, and craft persuasive written arguments to be read and evaluated by persons in authority positions. Unacceptable ratings on Project 2 resulted most often from underdeveloped arguments or less than thorough document editing. This difficulty reflected similar reports from multiple disciplines of students struggling to provide clear and appropriate linkages between experiences and program outcomes.18

Course faculty identified several educational outcome-specific themes within the students’ self-assessment: (1) students argued that they entered the PharmD program with a deep loyalty to the program’s core values, having been taught these values as children. Seeing these values practiced by their peers affirmed their beliefs; (2) the majority of students drew on their experiential education experiences exclusively to illustrate their growth as critical/analytic thinkers and problem solvers. Nonexperiential, didactic coursework was rarely mentioned as a developmental catalyst; (3) the majority of students did not like group work and collaboration. Having succeeded as individuals and shared the common experience of working in suboptimal groups, students accepted begrudgingly that group work was necessary in pharmacy. At the same time, however, they made clear connections between group tasks and the curriculum’s emphasis on group skills to prepare them for working with others in the future; (4) students expected to provide patient care, and saw themselves as well-prepared to do so as new members of the health care community; (5) the majority of students were less confident that they understood integrated health systems and the resources and processes that underlie complex systems. Many students’ comments recommended that faculty members address improving this area of student development; (6) regardless of whether or not they viewed writing and public speaking as pleasant, the students’ resulting artifacts demonstrated effective writing and presentation ability. Many students acknowledged the noticeable strides they made in improving their communication abilities across 4 years; (7) students were able to reflect on the impact choices have on their lives and how their choices controlled their future.

Students struggled with Project 3 (the CPD Plan) based on the initial and final assessment results (Tables 2 and 3), even though all students achieved a pass rating. Students found it difficult to forecast realistic work contexts, professional needs, and emerging opportunities. Few argued for concentrated continuing education (formal or informal) in their short-range or intermediate-range future other than residency training or mandatory continuing education programming. The CPD plans typified those of professional novices. However, because professional novice was the position in which these students found themselves as newly-minted pharmacists, this outcome was not disheartening; students left the program with a CPD plan off of which they could build, going forward.

When given the freedom in Project 4 to select a defining, singularly significant moment in their education and professional development, nearly every student rose to the challenge. They looked across their experience and identified many stories they believed were worth sharing in a public forum to their peers, faculty members, and guests. Faculty members observed that during the discursive process between students and faculty members, students worked to have their presentation topic approved, which led to a tightly-focused and relevant central message for their presentations; in other words, it demonstrated the students’ ability to seek and use expert advice and apply it to their work. Not one of the presentations included instances of inappropriate humor, unethical disclosure of sensitive information, or other hallmarks of presentations made by students earlier in their education. Faculty members also observed that the civility and respect of students extended to their peers during presentations—many of which were highly personal—was also a marked difference from their own cohort normative behavior in years past. In the opinion of faculty members, these presentations were made by individuals ready to join a professional community, who would be able to deploy the public speaking skills and appropriate social behaviors befitting a PharmD recipient.

Each year, university-managed course evaluations are made available to students at the end of the semester; participation is optional. Eighteen percent of the 2012 and 2013 students completed the evaluations, a response rate in line with university averages. Respondents reported that the capstone course projects required them to think critically, were challenging, and contributed to their learning. From the qualitative comments gathered in the student evaluations, some students viewed the capstone course as an inconvenience (returning to campus for 2 weeks prior to graduation); however, once the course convened and students came back together as a cohort of peers, the perception of inconvenience was negated by student engagement. After completing the course, students routinely thanked the course faculty members for the opportunity to reflect on and share their experiences. Additionally, students verbally reported appreciating the opportunity to gather and rebond as a community after being separated and isolated during their 10-month-long APPE courses.

DISCUSSION

Schools of pharmacy must demonstrate to stakeholders that students who complete the curriculum achieve specific abilities through engagement with the program of study. Many of these abilities or outcomes, however, such as critical thinking, self-assessment, written and oral communication, self-directed learning, and professionalism, cannot be easily documented. However, these were the educational outcomes the capstone course intended to assess just before students left the program.

Each project provided an artifact students could use to demonstrate they met entry-level performance expectations in these 4 ability areas. This end-of-program, integrated, reflective capstone course helped the program (1) document that each student had a complete and well-organized portfolio; (2) verify that each student understood the program’s educational outcomes and could articulate their achievement of these outcomes; (3) verify that students had an initial direction for their career and short-range and intermediate-range plans to achieve their goals; and (4) document one significant learning opportunity in each student’s preparation for independent practice.

A 1-hour course at the end of the curriculum is not without its challenges. Students are anxious to graduate, and without the mandate presented in this course, few, if any, would likely volunteer to spend time reflecting on 4 years of training in a systematic way. Some members of the college community continue to view the 2-week return to campus as an imposition on students, even though this requirement is made clear to all prospective and matriculated students. Moreover, once students understand the scope of the projects, they see the advantage of the course. The capstone course can create some short-term inconveniences for students and a few heavy grading days for faculty members. However, it is an opportunity to provide closure for the class after a significant number of experiences (individual and shared) spanning 4 years. Surveys of alumni will be conducted as well to determine how the course impacted their professional readiness.

SUMMARY

The PharmD capstone course at Belmont University’s College of Pharmacy is novel, measures critical educational outcomes, and captures artifacts that document student accomplishments. The course is offered at the end of the PharmD curriculum and covers APPE experiences in addition to the didactic and introductory pharmacy practice experience coursework in years 1-3. Unlike the narrow focus of the few capstone-like courses mentioned in the pharmacy literature, or described in pharmacy curricula, this integrative/reflective capstone model’s focus is broad, encompassing the student’s entire time in the program and more than one ability outcome. Students report learning from the experience, and the course provides them, the college, and the institution with artifacts that validate educational growth.

Appendix 1. Project Rubrics

Project One – Portfolio Completion Rubric

Student Name: Project Assessment: E A U (circle one)

Assessment:

Excellent (Pass)

An Excellent project addresses all required (and selected optional) portfolio elements with equal depth, detail, and quality. No elements call into question the author’s credibility either by inappropriate or inaccurate content, inappropriate comments or tone, or less than thorough editing across the entire portfolio. This level of performance differs from Acceptable due to the obvious care that the author has invested in the entire project.

Acceptable (Pass)

An Acceptable project includes all required (and selected optional) portfolio elements, although not all elements are developed with equal depth, detail, and quality. One or two elements may call into question the author’s engagement with the project either by inappropriate or inaccurate content, inappropriate comments or tone, or less than thorough editing.

Unacceptable (Fail)

An Unacceptable project meets one or more of the following: does not complete all required elements; does not establish a definitive sense of author commitment to developing a quality portfolio; does not maintain a professional persona throughout the portfolio; exhibits less than thorough editing.

Project 2 - Grading Rubric

Student Name: Project Assessment: E A U (circle one)

Excellent

An Excellent project addresses all outcomes with equal depth, detail, and honesty. The author is courteous and informed, yet independent and assured. In no way does a response call the author’s credibility into question, either by inappropriate comments, unsupported argument, unassertive author presence, or less than thorough editing of the document. This level of performance differs from Acceptable due to the obvious control that the author has established over the entire project.

Acceptable

An Acceptable project includes all elements mandated in the project, although two to three responses are less equal in their depth, detail, and honesty. There may be elements that call into question the information presented or the author’s credibility. Flaws may include inappropriate comments, unsupported argument, or less than thorough editing of the document. This level of performance differs from Unacceptable due to the completion of all required elements with an acceptable level of document completeness, correctness, accurateness, and cleanliness.

Unacceptable

An Unacceptable project fails to achieve one or more of the following: completes all required elements of the project; establishes a definitive sense of who the author is and why s/he is writing; displays appropriate levels of author courtesy and knowledge; maintains a professional persona that is independent and assured. There are distinct moments within the responses that call information or author credibility/professionalism into question, by inappropriate comments, unsupported argument, unassertive author presence, or less than thorough editing. There are many incidents of less than thorough editing, and these affect smooth reading of the document. This performance questions the author’s ability to perform activities expected of a pharmacy practitioner on the cusp of independent practice.

Notes/Comments/Suggestions:

Project 3 - Grading Rubric

Student Name: Project Assessment: E A U (circle one)

Excellent

An Excellent project addresses all parts of a complete CPD plan with equal depth, detail, and honesty. The author is clearly reflective, informed, independent, and logical. In no way does a response call the author’s credibility or sincerity into question, either by inappropriate comments, evidence of lack of maturity and engagement, unsupported argument, unassertive author presence, or less than thorough editing of the document. This level of performance differs from Acceptable due to the obvious control that the author has established over the entire project.

Acceptable

An Acceptable project includes all CPD elements mandated in the project, although one or two elements are less equal in their depth, detail, and evidence of honest engagement. There may be elements that call into question the information presented or the author’s credibility. Flaws may include inappropriate comments, of lack of maturity and engagement, unsupported argument, unassertive author presence, or less than thorough editing of the document. This level of performance differs from Unacceptable due to the completion of all required elements with an acceptable level of document completeness, correctness, accurateness, and cleanliness.

Unacceptable

An Unacceptable project fails to achieve one or more of the following: completes all required elements of the project; establishes a definitive sense of who the author is and why s/he is writing; displays appropriate levels of author maturity/engagement and knowledge; maintains a professional persona that is independent and assured. There are distinct moments within the document that call information or author credibility/professionalism into question by inappropriate comments, lack of maturity and engagement, unsupported argument, unassertive author presence, or less than thorough editing. There are many incidents of less than thorough editing, and these affect smooth reading of the document. This performance questions the author’s ability to perform activities expected of a pharmacy practitioner on the cusp of independent practice.

Notes/Comments/Suggestions:

Project 4 - Grading Rubric

Student Name: Grade: Pass Fail

REFERENCES

- 1.The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language. Fourth Edition. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wuller CA. A capstone advanced pharmacy practice experience in research. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(10) doi: 10.5688/aj7410180. Article 180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy Center for the Advancement of Pharmaceutical Education. Educational Outcomes 2004. http://www.aacp.org/resources/education/Documents/CAPE2004.pdf. Accessed January 29, 2014.

- 4.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation Standards and Guidelines for the Professional Program in Pharmacy Leading to the Doctor of Pharmacy Degree. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/FinalS2007Guidelines2.0.pdf. Accessed January 29, 2014.

- 5.Henscheid JM, Barnicoat LR. Capstone Courses in Higher Education – Types of Courses, the Future. StateUniversity.Com. http://education.stateuniversity.com/pages/1812/Capstone-Courses-in-Higher-Education.html. Accessed January 29, 2014.

- 6.Cuseo JB. The Senior Year Experience: Facilitating Reflection, Integration, Closure and Transition. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1998. Objectives and benefits of senior year programs. [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. AACP Commission to Implement Change in Pharmaceutical Education, Entry Level, Curricular Outcomes, Curricular Content and Educational Process, Background Paper II. http://www.aacp.org/resources/historicaldocuments/Documents/BackgroundPaper2.pdf. Accessed January 29, 2014.

- 8.Chalmers RK, Gibson RD, Schumacher GE, et al. Liberal education – a key component in pharmacy education Report of the 1986-87 Argus Commission. Am J Pharm Educ. 1987;51:446–450. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chalmers RK, Grotpeter JJ, Hollenbeck G, et al. Changing to an outcome-based, assessment-guided curriculum: a report of the Focus Group on Liberalization of the Professional Curriculum. Am J Pharm Educ. 1994;58(1):108–15. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schön DA. Educating the Reflective Practitioner: Toward a New Design for Teaching and Learning in the Professions. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Speedie MK, Baldwin JN, Carter RA, et al. Cultivating “habits of mind” in the scholarly pharmacy clinician: Report of the 2011-12 Argus Commission. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76(6) doi: 10.5688/ajpe766S3. Article S3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Marcia A. McDonald, PhD. Personal communication, 2008.

- 13.Bloom B.S., editor. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives Book 1: Cognitive Domain. White Plains, N.Y: Longman; 1956. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bonwell CC, Eison JA. Active learning: creating excitement in the classroom. ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report No. 1. Washington, D.C: The George Washington University; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cotterell A, Janus Storm R. The Ultimate Encyclopedia of Mythology. London, England: Hermes House; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1960;20(1):37–46. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Plaza CM, Drauglias JR, Slack MK, Skrepnek GH, Sauer KA. Use of reflective portfolios in health sciences education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(2) doi: 10.5688/aj710234. Article 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]