SUMMARY

Previous reports focusing on the high prevalence of voice disorders in teachers have suggested that vocal loading might be the main causal factor. The aim of our study was to assess the prevalence of voice disorders in a sample of primary school teachers and evaluate possible cofactors. Our sample was composed of 157 teachers (155 females, mean age 46 years). Participants were asked to complete two selfadministrated questionnaires: one with clinical data, and the second an Italian validated translation of VHI (voice handicap index). On the same day they also underwent a laryngostroboscopic exam and logopedic evaluation. The results were compared with those of a control group composed of accompanying individuals. Teachers presented a higher rate of abnormalities at laryngostroboscopic examination than the control group (51.6% vs. 16%, respectively). Among these, 7.1% presented nodules. In our sample, vocal fold disorders were not correlated with years of teaching, smoking, coffee consumption, or levels of anxiety. Our findings are in agreement with previous reports on the prevalence of pathologic disorders among teachers; nonetheless, the prevalence of nodules was lower than in previous investigations, and voice loading was not correlated with laryngostroboscopic findings. Current Italian law does not include any guidance regarding voice education and screening in subjects with high vocal loading. Our work stresses the need for such legislation.

KEY WORDS: Voice disorders, Vocal folds nodules, Laryngostroboscopy, Teachers

RIASSUNTO

Lavori precedenti hanno focalizzato l'attenzione su una elevata prevalenza dei disturbi vocali negli insegnanti ed il sovraccarico vocale potrebbe esserne il principale responsabile; scopo dello studio è stato quello di valutare tale prevalenza in un campione di insegnanti delle scuole dell'infanzia e determinare eventuali concause. Il campione studiato era costituito da 157 insegnanti (155 donne, con età media di 46 anni). è stato loro chiesto di completare due questionari: il primo riguardante la storia clinica, il secondo costituito dalla versione italiana del VHI (Voice Handicap Index). Nella stessa giornata sono stati sottoposti a laringostroboscopia ed a valutazione logopedica. I risultati sono stati comparati con quelli di un gruppo di controllo costituito dalle persone che accompagnavano gli insegnanti. Gli insegnanti presentavano un tasso più elevato di anomalie all'esame laringostroboscopico rispetto ai controlli (51.6% vs. 16%). Tra gli insegnanti il 7.1% presentava noduli delle corde vocali. Nel nostro campione non è emersa alcuna correlazione tra i disordini vocali e l'età di insegnamento, il fumo, il consumo di caffè ed il livello di ansia. I nostri risultati concordano con la letteratura riguardo la prevalenza di alterazioni tra gli insegnanti; tuttavia la prevalenza di noduli è risultata minore rispetto a quello registrata in lavori precedenti ed il carico vocale non ha presentato correlazioni con i rilievi laringostroboscopici. La legge italiana non prevede protocolli di educazione vocale e di screening nei soggetti con elevato carico vocale. Il nostro lavoro ne sottolinea la necessità.

Introduction

Subjects using their voice as a professional instrument more frequently develop voice disorders; among these, teachers present a high prevalence of voice changes compared with other professional categories 1-3; voice changes may arise from interaction of occupational (vocal loading), behavioural and lifestyle factors.

Vocal loading is defined as a combination of the duration of voice use and environmental features; teachers are often obliged to use load voice without any amplification for several hours a day 4.

Different papers report a correlation between voice disorders and the length of time working as a teacher. Moreover, among environmental factors, teachers working in noisy rooms present a higher rate of voice disorders and a higher score in voice handicap index (VHI) questionnaire 3 5 6.

During their professional education, a small number of teachers receive information about the correct use of voice 7. Some also undergo medical evaluation 8, since logopaedic therapy may be useful in the treatment of dysfunctional dysphonia 9.

Voice disorders provoked by professional use are more often chronic and can lead to an increase in working days missed 4 8 10. Nodules in teachers have been reported to be present in 13-14% of individuals 11 12.

Other factors have been correlated with voice disorders and nodules in teachers, including sex (women are more frequently affected), age between 40 and 59 years and family history of voice disorder 3 13.

Job stress may play a bidirectional role; highly stressed teachers more frequently present voice disorders 14 and subjects with high strain are at risk for developing physical and mental stress 15 16.

Lifestyle related factors (smoking, alcohol and coffee consummation, infections of the upper respiratory tract) have been described as cofactors for voice disorders, although one report has suggested that they are correlated with voice disorders mostly in other professional categories rather than in teachers 17.

Several investigations have assessed voice quality with questionnaires 3 15 18 19, while those based on stroboscopic evaluation have reported a high prevalence of vocal fold alterations 12 20. Laryngostroboscopy is an endoscopic procedure that allows evaluation of vocal fold vibratory function during phonation 21.

The aim of our study was to assess the prevalence of vocal fold disorders and quality of voice in a sample of primary school teachers through self-completed questionnaires, laryngostroboscopic examination and logopaedic evaluation.

Materials and methods

Our sample was composed of 157 teachers (155 females, 2 males) aged between 28 and 60 years (mean 46 ± 8), from 23 primary schools randomly selected in the city of Milan. The average duration of teaching was 22 years.

The results were compared with those of a control group consisting of 75 subjects (72 females, 3 males) aged between 22 and 75 years (mean 43 ± 11). This sample was randomly selected among individuals accompanying the teachers and who did not perform work with high vocal loading. Since most teachers were females, the vast majority of the controls were also females.

All subjects were examined at the outpatient clinic of San Raffaele Resnati in Milan. Data were collected between March 2011 and July 2012.

Questionnaires

Before clinical evaluation, subjects were asked to complete two self-administered questionnaires. The first, composed of 21 questions and mainly based on clinical experience, is designed to gather general information on the patient's health and more specific elements regarding voice disorders 22. Subjects were asked to provide the following information: personal data (gender, age, name of school), behavioural habits (smoking, alcohol, caffeine), health conditions related to voice disorders (diseases, interventions, drugs, endocrine disorders), occupation (years of teaching, methods of use of voice), voice symptoms and physical discomfort (frequency of any disorder, symptoms of hoarseness, throat disorders, previous specialist consultations), effect of voice problems (changes in teaching method, influence on work, ability to communicate, ability to socialise, and emotional interference).

The second questionnaire is the Italian validated translation 23 of the VHI 24, a voice-related quality of life tool. It is divided into physical (P), emotional (E) and functional subscales (F). The questionnaire consists of 30 questions and answers are rated on a five-point scale "0 = never", "1 = almost never," "2 = sometimes," "3 = almost always", "4 = always" . Each of the three parts has a maximum score of 40 points that corresponds to serious pathological situation. Only teachers were asked to complete the questionnaires.

Clinical examination

Both groups underwent laryngostroboscopic evaluation. In the sample of teachers, two refused to undergo laryngoscopic examination.

Laryngeal examination was performed with a XION flexible endoscope in combination with multifunctional videolighting Nomad C (Portable ENT Endoscopy and Documentation System – XION - Germany), which includes both a continuous and strobe source of light. The results were archived using a video-recording program (Divas software). After examination of laryngeal morphology in a normal white light source, vocal function was assessed with strobe light during pronunciation of the vowel /i/. Fundamental frequency was assessed. During the continuous light examination, morphological evaluation of vocal folds was performed.

During the stroboscopic exam, parameters modified by Ricci Maccarini 25 and based on the criteria encoded by Hirano were saved 26: motility, profile, morphology, vibration amplitude, frequency, symmetry, glottic closure, mucosal wave, place of the phonatory vibration and attitude of supraglottic structures. In order to facilitate the collection of information, a summary form was used.

Logopaedic evaluation was made with MDVP (multidimensional voice program, KayPentax, Japan) software, while subjects were asked to pronounce a prolonged (at least 10 sec) vowel /a/; parameters were obtained from the 3 central seconds previously sampled at 50,000 Hz.

During acoustic analysis, we considered, in addition to the fundamental frequency, the 11 parameters recommended by De Colle 27: 1) Jitt% = Jitter Percent (Fundamental Period), 2) vF0% = Fundamental Frequency Variation, 3) Shim% = Shimmer percent (Width of Peak), 4) vAm% = Peak-Amplitude Variation, 5) NHR = Noise to Harmonic Ratio, 6) VTI = Voice Turbulence Index, 7) SPI = Soft Phonation Index, 8) FTRI% = Frequency Tremor Index, 9) ATRI% = Amplitude Tremor Index, 10) DVB% = Degree of Voice Breaks, 11) DSH% = Degree of Sub-harmonics.

Statistical analysis

Data were coded and recorded in an Excel database; statistical analysis was performed with SPSS software (SPSS 21.0). For all data, we carried out frequency analysis and descriptive statistics; different statistical methods were applied depending on the variable analysed. In all statistical analyses, a p < 0.05 was considered significant. To compare categorical variables between groups, a Chisquare (χ2) or Fisher's exact test was used, as appropriate. Data are presented as n (number of cases) and % (percentage within group). To compare continuous variables a Student's t test was used for independent samples or a Mann-Whitney test for variables not showing a normal distribution. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare three or more groups. Data are presented as means ± SD (standards deviation). To compare the rate of laryngostroboscopic alterations in relation with teaching experience, the median age of teaching was used. Since males present a lower fundamental frequency, values of the 2 males in teachers group and the 3 males in the control group were not considered in statistical analysis.

Results

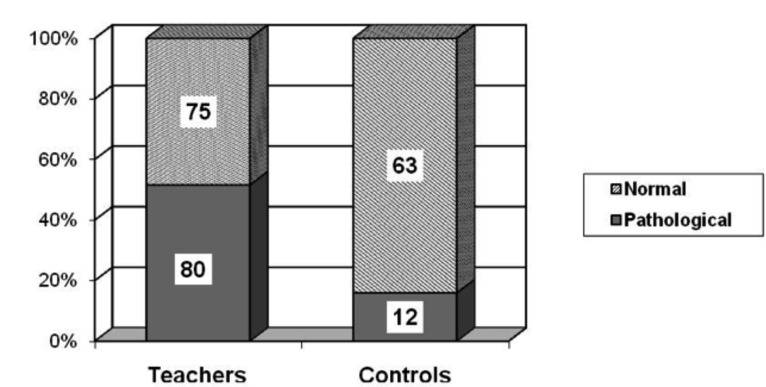

There was no significant difference between teachers and controls considering age. Teachers presented a higher rate of abnormalities at laryngostroboscopic examination than controls (51.6% vs. 16%, respectively, χ2= 26.71; p < 0.001). Results are shown in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Histogram of laryngostroboscopic abnormalities in teachers and controls.

The presence of any anomalies in stroboscopic parameters or laryngoscopic evidence of vocal cord pathology were considered as abnormal in laryngostroboscopic examination. The observed laryngoscopic vocal cord pathologies in both groups are summarised in Table I.

Table I.

Observed vocal cord pathologies. * χ2 test or Fisher's exact test.

| Teachers | Controls | P* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n/N) | % | (n/N) | % | ||

| Cordal thickening | 7/155 | 4.5 | 0/75 | 0.0 | 0.09 |

| Capillary ectasia | 6/155 | 3.9 | 0/75 | 0.0 | 0.18 |

| Nodules | 11/155 | 7.1 | 0/75 | 0.0 | 0.02 |

| Sulcus | 5/155 | 3.2 | 1/75 | 1.3 | 0.67 |

| Reinke's oedema | 2/155 | 1.3 | 1/75 | 1.3 | 0.99 |

| Pre-contact | 4/155 | 2.6 | 0/75 | 0.0 | 0.31 |

| Cysts | 1/155 | 0.6 | 2/75 | 2.7 | 0.25 |

Among teachers, 7.1% presented nodules. Table II details the stroboscopic anomalies in both groups. Teachers with anomalies of glottic closure more frequently presented incomplete closure (38 of 46 cases), while the mucosal wave was of small amplitude in 36 of 39 teachers with abnormalities.

Table II.

Anomalies in stroboscopic parameters. * χ2 test or Fisher's exact test

| Teachers N = 155 |

Controls N = 75 |

P* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n/N) | % | (n/N) | % | ||

| Motility vocal folds | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | |

| Profile vocal folds | 11 | (7.1) | 4 | (5.3) | 0.78 |

| Morphology vocal folds | 21 | (13.5) | 2 | (2.7) | 0.01 |

| Morphology false vocal folds | 2 | (1.3) | 0 | (0.0) | 0.99 |

| Vibration amplitude vocal folds | 6 | (3.9) | 0 | (0.0) | 0.18 |

| Frequency vibratory cycle | 9 | (5.8) | 2 | (2.7) | 0.51 |

| Symmetry cordal vibration | 21 | (13.5) | 4 | (5.3) | 0.06 |

| Glottic closure | 46 | (29.7) | 3 | (4.0) | <0.01 |

| Morphology incomplete glottic closure | 45 | (29.0) | 3 | (4.0) | <0.01 |

| Mucosal wave | 39 | (25.2) | 2 | (2.7) | <0.01 |

| Place of the phonatory vibration | 1 | (0.6) | 0 | (0.0) | 0.99 |

| Attitude of supraglottic structures | 1 | (0.6) | 0 | (0.0) | 0.99 |

The median age of teaching was 22 years. Comparing the presence of vocal fold pathology with years of teaching, a higher frequencies of abnormalities in individuals with fewer years of teaching was observed, although the difference was not statistically significant. The results are shown in Table III (χ2 = 1.64; p = 0.2).

Table III.

Contingency table between years of teaching experience (median 22 years) and vocal folds abnormalities.

| Laryngostroboscopy | Teaching experience | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| More than 22 years (N) | Less than 22 years (N) | ||

| Normal | 42 | 33 | 75 |

| Pathologic | 36 | 44 | 80 |

| Total | 78 | 77 | 155 |

Teachers demonstrated a lower fundamental frequency than controls (174.9 ± 27.4 vs. 235.9 ± 29.6; Mann Whitney test, p < 0.001). Subjects with abnormalities at laryngostroboscopic examination showed a lower fundamental frequency (181.9 ± 35.1 vs. 202.0 ± 43.8; Mann Whitney test, p < 0.001). Parameters of multiparametric voice analysis obtained with the MDVP system are listed in Table IV.

Table IV.

Parameters of voice analysis in teachers and controls. *Student's t-test or Mann-Whitney test.

| Teachers | Controls | P* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| F0 (Hz) | 192.34 | 33.45 | 205.49 | 33.70 | <0.01 |

| Jitt% | 1.85 | 1.37 | 0.83 | 0.77 | <0.01 |

| Vf0% | 4.95 | 7.59 | 2.13 | 4.32 | <0.01 |

| Shim% | 7.31 | 3.19 | 4.34 | 2.02 | <0.01 |

| vAm% | 17.63 | 6.52 | 19.19 | 8.38 | 0.26 |

| NHR | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.04 | <0.01 |

| VTI | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.02 | <0.01 |

| SPI | 9.72 | 5.43 | 5.61 | 2.92 | <0.01 |

| FTRI% | 0.55 | 0.66 | 0.41 | 0.39 | 0.01 |

| ATRI% | 5.50 | 3.68 | 6.74 | 3.63 | 0.02 |

| DVB% | 0.74 | 2.67 | 0.69 | 5.94 | <0.01 |

| DSH% | 3.32 | 4.27 | 1.26 | 3.38 | <0.01 |

The following was reported in the first questionnaire: smoking (22.4%), alcohol (8.3%), coffee consumption (84%), respiratory tract infections (70.5%), nasal allergy (34.6%), deviation of the nasal septum (17.9%), hormonal problems (21.2%), gastro oesophageal reflux disease (32.1%), stress (59.4%), anxiety (50%), surgery (9.6%), chronic treatment (29%) and hormonal disorder (26.5%). None of the parameters collected with the first questionnaire was associated with laryngostroboscopic anomalies (Table II).

During teaching activities, 17.3% of teachers declared to use a low tone, 62.8% a moderate tone and 19.9% a high tone. No correlation was found with abnormalities at laryngostroboscopy (χ2 = 1.4; p = 0.5). However, the reported frequency of voice disorders (0.9% never, 62.8% sometimes, 23.1% often and 3.2% always) was associated with the presence of disorders at laryngostroboscopic examination (χ2 = 17.5; p = 0.001).

Among teachers, 77.6% presented hoarseness, 27.6% shortness of breath, 28.8% tired voice, 35.3% weak voice, 21.8% fatigable voice, 13.5% difficulty to use bass tones, 37.2% difficulty to use high tones, 18.6% need to use low tone voice, 26.3% need to use high tone voice, 55.8% referred dry throat, 46.8% sore throat and 40.4% dysphagia. Previously reported laryngostroboscopic alterations were significantly correlated with tired voice (35.56% without anomalies vs. 64.44% with; p = 0.04), weak voice (31.48% vs. 68.52%; p = 0.002), difficulty to use bass tones (19.05% vs. 80.95%; p = 0.004) and difficulty to use high tones (34.48% vs. 65.52%; p = 0.007).

Only 31 of 155 teachers reported previous ENT consults for voice disorders; 26.3% of teachers with abnormalities at laryngostroboscopic examination had never undergone medical consultation for the problem.

Finally, the first questionnaire investigated the effect of voice disorders on social and professional activities of teachers: 31.4% reported having modified/adapted their teaching method, 37.2% changed judgment on the profession of educator, 42.3% changed their way of communicating, 5.8% reported a change in their social skills and 20.5% reported interference with their emotional state. Comparison of the effects of voice disorders with the presence of laryngostroboscopic anomalies shows a significant correlation with interference on emotional state (5.8% with anomalies vs. 14.8% without; χ2 = 6.629; p = 0.01).

The scores in the second questionnaire (VHI test) showed a distribution in the range between 0 and 64 (median 12). The VHI score was higher in subjects with laryngostroboscopic disorders than in the other subgroup (18.35 ± 13.8 vs. 13.45 ± 11.46; Mann-Whitney test, p = 0.026).

Discussion

The aim of the present investigation was to assess the prevalence of voice disorders in teachers using both anamnestic and clinical evaluation. Several previous reports have focused on the same problem using self-administered questionnaires, with a prevalence of voice disorders of 32.1% to 68.7% of teachers and a 3.5-fold increased risk of developing voice disorders during their occupational life 18 28-30. A previous study reported a prevalence of 20.2% of organic lesions, 29% of functional disorders and 8% of chronic laryngitis in a teaching staff in Spain; subjects were studied with questionnaires, functional vocal examination, acoustic analysis and videolaryngostroboscopy 12. In our sample, the prevalence of pathologic subjects was 51.6% vs. 16% of controls, in accordance with previous publications 11.

The most frequent laryngostroboscopic findings included reduced amplitude of the vocal wave associated with phase asymmetries (29% of teachers) and vocal fold hypotrophy with incomplete glottic closure (11% of teachers). These anomalies may arise from persistent vocal adaptation to increased vocal loading, and may be anatomically correlated with weakened vocal muscle 31.

On the other hand, we found vocal fold nodules in only 7.1% of teachers; in previous reports, the prevalence has ranged from 6% to 14% 11 30 32 33.

Notably, 35.5% of teachers presented clinical symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux, compared with only 2.7% of controls; since gastro-oesophageal reflux may be potentiated by psychological stress 34, it is likely that emotional factors may play a role in this finding.

Although previous papers have identified several cofactors for increased risk of voice disorders 14 29 32, smoking, coffee and stress, in our sample none of these factors correlated with laryngostroboscopic abnormalities. In contrast, we found that job-related stress correlated with the duration of teaching, and it should be noted that a high proportion of teachers referred that voice disorders interfered with their emotional state and social activities.

In our sample, vocal fold disorders were not correlated with years of teaching, and teachers with fewer years of teaching presented a higher rate of abnormalities than subjects with a longer job activity. One possible explanation for this finding is that younger teachers have less experience in job related voice practice, and some subjects may present an "intrinsic predisposition" to develop vocal fold abnormalities.

Finally, it must be underlined that 85.9% of the total sample declared voice disorders at some time during teaching; nonetheless, only 20% of these, and 26.3% of subjects with focal fold abnormalities, underwent medical consultation for the problem. The finding has already been reported in other reports 3 8. It has been hypothesised that teachers consider voice problems an "expectable problem" and that they are unaware that there are therapeutic possibilities that can reduce or prevent them.

Conclusions

Our study highlights the high prevalence of laryngostroboscopic anomalies in teachers, although only a relatively small proportion presented nodules. Vocal loading may play a role in these findings, although vocal fold disorders did not correlate with years of teaching. In our opinion, the present study stresses the need for a preventive voice program for all teachers, possibly at the beginning of their work activity 35.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- VHI

Voice Handicap Index

- ICAWS

Interpersonal Conflict at Work Scale

- OCS

Organizational Constraints Scale

- QWI

Quantitative Workload Inventory

- PSI

Physical Symptoms Inventory

- MDVP

Multi-Dimensional Voice Program

- F0

Average Fundamental Frequency (Hz)

- Jitt%

Jitter Percent (Fundamental Period)

- vF0%

Fundamental Frequency Variation

- Shim%

Shimmer percent (Width of Peak)

- vAm%

Peak-Amplitude Variation

- NHR

Noise to Harmonic Ratio

- VTI

Voice Turbulence Index

- SPI

Soft Phonation Index

- FTRI%

Frequency Tremor Index

- ATRI%

Amplitude Tremor Index

- DVB%

Degree of Voice Breaks

- DSH%

Degree of Sub-harmonics

- GERD

Gastro-Oesophageal Reflux

References

- 1.Williams NR. Occupational groups at risk of voice disorders: a review of the literature. Occup Med (Lond) 2003;53:456–460. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqg113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith E, Lemke J, Taylor M, et al. Frequency of voice problems among teachers and other occupations. J Voice. 1998;12:480–488. doi: 10.1016/s0892-1997(98)80057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roy N, Merrill RM, Thibeault S, et al. Prevalence of voice disorders in teachers and the general population. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2004;47:281–293. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2004/023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roy N, Weinrich B, Gray SD, et al. Voice amplification versus vocal hygiene instruction for teachers with voice disorders: a treatment outcomes study. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2002;45:625–638. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2002/050). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Araujo TM, Reis EJ, Carvalho FM, et al. [Factors associated with voice disorders among women teachers]. Cad Saude Publica. 2008;24:1229–1238. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2008000600004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ceballos AG, Carvalho FM, Araujo TM, et al. Auditory vocal analysis and factors associated with voice disorders among teachers. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2011;14:285–295. doi: 10.1590/s1415-790x2011000200010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Houtte E, Claeys S, Wuyts F, et al. The impact of voice disorders among teachers: vocal complaints, treatmentseeking behavior, knowledge of vocal care, and voice-related absenteeism. J Voice. 2011;25:570–575. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Costa V, Prada E, Roberts A, et al. Voice disorders in primary school teachers and barriers to care. J Voice. 2012;26:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schindler A, Mozzanica F, Ginocchio D, et al. Vocal improvement after voice therapy in the treatment of benign vocal fold lesions. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2012;32:304–308. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Medeiros AM, Assuncao AA, Barreto SM. Absenteeism due to voice disorders in female teachers: a public health problem. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2012;85:853–864. doi: 10.1007/s00420-011-0729-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Preciado-Lopez J, Perez-Fernandez C, Calzada-Uriondo M, et al. Epidemiological study of voice disorders among teaching professionals of La Rioja, Spain. J Voice. 2008;22:489–508. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2006.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Preciado J, Perez C, Calzada M, et al. [Prevalence and incidence studies of voice disorders among teaching staff of La Rioja, Spain. Clinical study: questionnaire, function vocal examination, acoustic analysis and videolaryngostroboscopy]. Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp. 2005;56:202–210. doi: 10.1016/s0001-6519(05)78601-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lauriello M, Angelone AM, Businco LD, et al. Correlation between female sex and allergy was significant in patients presenting with dysphonia. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2011;31:161–166. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roy N, Bless DM. Personality traits and psychological factors in voice pathology: a foundation for future research. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2000;43:737–748. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4303.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giannini SP, Latorre Mdo R, Ferreira LP. [Voice disorders related to job stress in teaching: a case-control study]. Cad Saude Publica. 2012;28:2115–2124. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2012001100011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lauriello M, Cozza K, Rossi A, et al. Psychological profile of dysfunctional dysphonia. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2003;23:467–473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Helidoni M, Murry T, Chlouverakis G, et al. Voice risk factors in kindergarten teachers in Greece. Folia Phoniatr Logop. 2012;64:211–216. doi: 10.1159/000342147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Angelillo M, Maio G, Costa G, et al. Prevalence of occupational voice disorders in teachers. J Prev Med Hyg. 2009;50:26–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Souza CL, Carvalho FM, Araujo TM, et al. Factors associated with vocal fold pathologies in teachers. Rev Saude Publica. 2011;45:914–921. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102011005000055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sataloff RT, Hawkshaw MJ, Johnson JL, et al. Prevalence of abnormal laryngeal findings in healthy singing teachers. J Voice. 2012;26:577–583. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mehta DD, Hillman RE. Current role of stroboscopy in laryngeal imaging. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;20:429–436. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0b013e3283585f04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen SH, Chiang SC, Chung YM, et al. Risk factors and effects of voice problems for teachers. J Voice. 2010;24:183–190. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schindler A, Ottaviani F, Mozzanica F, et al. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Voice Handicap Index into Italian. J Voice. 2010;24:708–714. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jacobson B, Johnson A, Grywalsky C, et al. The Voice Handicap Index (VHI): development and validation. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 1997;6:66–70. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ricci-Maccarini A, Nicola V. La valutazione dei Risultati del Trattamento Logopedico delle Disfonie. Padova: Ed. La Garangola; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirano M, Bless D. Videostroboscopic examination of the larynx. San Diego: Ed. Singular Publishing Group Inc; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Colle W. Voce & Computer: Analisi acustica digitale del segnale verbale (Il sistema CSLMDVP) Turin: Ed. Omega; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Charn TC, Hwei Mok PK. Voice problems amongst primary school teachers in singapore. J Voice. 2012;26:141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nerriere E, Vercambre MN, Gilbert F, et al. Voice disorders and mental health in teachers: a cross-sectional nationwide study. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:370–370. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sliwinska-Kowalska M, Niebudek-Bogusz E, Fiszer M, et al. The prevalence and risk factors for occupational voice disorders in teachers. Folia Phoniatr Logop. 2006;58:85–101. doi: 10.1159/000089610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Obrebowski A, Pruszewicz A, Sulkowski W, et al. [Proposals of rational procedures for certifying occupational voice disorders]. Med Pr. 2001;52:35–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sala E, Laine A, Simberg S, et al. The prevalence of voice disorders among day care center teachers compared with nurses: a questionnaire and clinical study. J Voice. 2001;15:413–423. doi: 10.1016/S0892-1997(01)00042-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Preciado JA, Garcia Tapia R, Infante JC. [Prevalence of voice disorders among educational professionals. Factors contributing to their appearance or their persistence]. Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp. 1998;49:137–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kamolz T, Velanovich T. Psychological and emotional aspects of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Diseases of Esophagus. 2002;15:199–203. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2050.2002.00261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bovo R, Galceran M, Petruccelli J, Hatzopoulos S. Vocal problems among teachers: evaluation of a preventive voice program. J Voice. 2007;21:705–722. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]