Abstract

Mayaro virus (MAYV) is widely distributed throughout South America and is the etiologic agent of Mayaro fever, an acute febrile illness often presenting with arthralgic manifestations. The true incidence of MAYV infection is likely grossly underestimated because the symptomatic presentation is very similar to that of dengue fever and other acute febrile tropical diseases. We report the complete genome sequence of a MAYV isolate detected from an Acrelândia patient presenting with fever, chills, and sweating, but with no arthralgia. Results show that this isolate belongs to genotype D and is closely related to Bolivian strains. Our results suggest that the Acre/Mayaro strain is closely related to the progenitor of these Bolivian strains that were isolated between 2002 and 2006.

Mayaro virus (MAYV) is a member of the genus Alphavirus, family Togaviridae. It is widely distributed in Brazil, having been detected in the Amazonia, Central and Northeastern regions.1–5 Outbreaks of arthralgic disease caused by MAYV are usually limited to rural areas within/near rainforests where the mosquito vector Haemagogus janthinomys is abundant.6 The virus is endemic in many parts of the Amazon region of Brazil, with high seropositivity levels among the local populations (typically 5–60%).7–9 However, human viremia is short-lived (around 3 days), thereby making virus isolation from serum samples very difficult.6 Non-human primates and possibly migratory birds are important for enzootic virus circulation.6 The MAYV also has the potential to be transmitted in urban settings by the Aedes aegypti mosquito,10 which is widely distributed in Brazilian cities.11

Human infections caused by MAYV have been described in several countries, including Trinidad,12 Bolivia,13,14 French Guiana,15 Peru,14,16 Venezuela,17 and Brazil.7,18,19 In 1978, during an epidemic in Belterra, Pará State, Brazil, the virus was isolated from 43 patients.7 In 2000, in São Paulo state (Southeast Brazil), MAYV was isolated from a patient who had been fishing in Mato Grosso do Sul State.2 During 2007–2008, surveillance for acute febrile illness cases was performed in Manaus, Amazonia State, and 5.2% of all patients presented with anti-MAYV immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies.19

Phylogenetic studies of MAYV based on the E1/E2 envelope glycoprotein genes have recognized two major lineages: Genotype D includes isolates from 1954 to 2003, including samples from Trinidad, Brazil, French Guiana, Surinam, Peru and Bolivia, and Genotype L contains six isolates from the north-central Brazil, isolated between 1955 and 1991.20

Herein, we describe a case of MAYV infection that occurred in Acre, Amazon Basin, Brazil. We also compare the complete genomic sequence of our isolate with those currently available in GenBank to identify its phylogenetic relatedness to other MAYV strains.

The patient was identified in June, 2004, during an ongoing epidemiological survey, in Acrelância, Acre State, Brazil, which is located in the Western Amazon Basin, bordering with Peru, Bolivia, and the Brazilian states of Amazonas and Rondônia. The blood sample was collected from a 27-year-old malaria-negative female patient presenting with fever, chills, and sweating. The patient was recruited at a health post during a population-based survey of acute febrile illnesses and examined for signs and symptoms of arboviral infections at the time of recruitment. The study was approved by the Ethical Review Board of the Institute of Biomedical Sciences of the University of São Paulo, Brazil (protocol 538/2004) and additional epidemiological features of this survey were described previously by Silva-Nunes and others, 2008.21

The patient had a non-complicated disease and completely recovered. No signs or symptoms of joint pain, swelling, or arthralgia were recorded at the time of the recruitment, but no follow-up was performed, therefore it is unclear if the characteristic arthralgic symptoms of MAYV infection arose after initial examination. The RNA was extracted from the patient's serum and multiplex-nested reverse transcription-polymerase chain reactions (RT-PCRs) performed for several flaviviruses and alphaviruses as described by Bronzoni and others, 2005.22 The sample was RT-PCR-positive for MAYV, and the virus was subsequently isolated in C6/36 mosquito cells and the multiplex-nested RT-PCR was used to confirm MAYV infection in the culture supernatant. Viral RNA was obtained using the QIAamp Viral RNA Kit (Qiagen, Germany), double strand complementary DNA (cDNA) was prepared according to Green and Sambrook (2012),23 and Nextera-XT DNA (Illumina, San Diego, CA) was used to prepare the library that was sequenced with the MiSeq v3 Reagent Kit, 150 cycles (Illumina) in the MiSeq System (Illumina). Geneious R6 (Biomatters, Auckland, New Zealand) was used to assemble the sequence using a Brazilian MAYV complete genome (accession NC_003417) as a reference. De novo assembly was also performed with the reads based on the assembled contig to confirm the sequence. The sequence has been submitted to GenBank under accession no. KM400591.

The Acre/Mayaro sequence was manually aligned with MAYV sequences available in the GenBank database using Se-Al (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/seal/). A set of 61 taxa representing all available partial E2-E1 envelope glycoprotein sequences was prepared and used for phylogenetic analysis. A Bayesian phylogeny was inferred in Mr. Bayes24 using the General Time Reversible (GTR+I+Γ4) nucleotide substitution model. The analysis was performed for 1 million steps sampling every 1,000 and discarding the first 10% as burn-in.

Silva-Nunes and collaborators (2006)3 previously reported strong evidence of MAYV circulation and human infection in Acre state. Approximately half of the individuals sampled who were seropositive for MAYV were native Acreans, but the virus was never isolated there. Our study further supports their suggestion of endemicity with the isolation of MAYV from a serum sample collected in 2004.

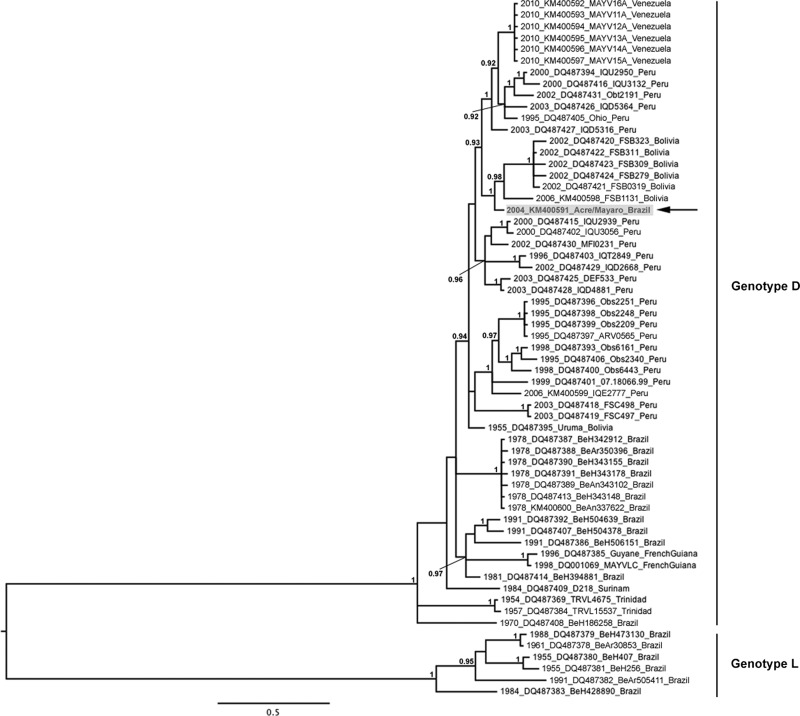

Our Bayesian phylogeny supports the MAYV genetic structure previously described by Powers and others,20 with both genotypes being clearly delineated. The Acre/Mayaro strain grouped most closely with Bolivian strains isolated between 2002 and 2006 within genotype D (Figure 1). This result was not unexpected given the proximity of Acre state to Bolivia. In our phylogeny, the Acre/Mayaro strain was positioned basal to the clade containing the Bolivian strains, suggesting that it is closely related to the progenitor for these Bolivian strains. However, the Acre/Mayaro isolate was phylogenetically distinct from the Bolivian strains with which it clustered, and from all previously published Brazilian sequences. This relationship was supported by the high posterior probability value (> 0.99) at the node supporting the Acre/Mayaro branch. According to its position in the phylogeny and its genetic divergence from other Brazilian strains isolated between 1978 and 1991 (92.1–98.8% nt sequence identity), relative to Bolivian strains isolated between 1955 and 2006 (98.8–99.3% nt sequence identity), and Peruvian strains isolated between 1995 and 2003 (98.6–99.4% nt sequence identity), Acre/Mayaro may represent another circulating phylogenetically distinct lineage within Brazil. However, there are very limited sequence data available for Brazilian MAYV strains after 1991, and these would be required to confirm this finding.

Figure 1.

Midpoint-rooted Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) phylogeny based on Mayaro virus (MAYV) partial E2-E1 sequences. Numbers at nodes indicate posterior probabilities ≥ 0.9. Taxon/tip labels include years of isolation, accession numbers, strain names, and countries where the virus was isolated. Scale bar shows percent nucleotide sequence divergence. Acre/Mayaro sequence is highlighted in gray and indicated with an arrow.

Human MAYV infections are strongly associated with occupational or recreational exposure in rainforest environments.25 However, increasing intercontinental travel and tourism-based forest excursions have increased the chance of acquiring these infections and possibly spreading the virus internationally. Therefore, infectious disease specialists need to be aware of febrile illnesses followed by persistent arthralgia, as patients can be easily misdiagnosed because Mayaro disease is not well known outside endemic regions.25–27

The threat of Mayaro and other arbovirus outbreaks (Dengue virus [DENV], Yellow fever virus [YFV], St. Louis encephalitis virus [SLEV], Chikungunya virus [CHIKV], Oropouche virus [OROV], equine encephalitis viruses, etc.) is extremely important to public health in the Americas and warrants further surveillance as part of an effective control program for humans and domestic animals. However, the epidemiology of the diseases caused by them is poorly explored in Brazil and other South America countries,1,28 because laboratory diagnostics for suspected cases are generally unavailable and clinical diagnosis based on signs and symptoms is difficult.1

This study reports the symptomatic profile of a patient presenting with Mayaro fever in the absence of acute arthralgia. The sequence reported here is the first to be described from Brazil in ∼15 years and represents a genetically distinct Brazilian MAYV lineage. Surveillance of healthy at risk populations and those presenting with acute undifferentiated febrile illnesses will be the best approach to understanding the epidemiology and clinical presentation of MAY disease among infected individuals.

Disclaimer: The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Financial support: This work was supported by INCT-Dengue and FAPESP (grant no. 2012/11733-6 to MLN). AJA was supported by the James W. McLaughlin Endowment fund.

Authors' addresses: Ana Carolina B. Terzian, Danila Vedovello, and Maurício L. Nogueira, Faculdade de Medicina de São José do Rio Preto, São José do Rio Preto, SP, Brazil, E-mails: anacarolinaterzian@gmail.com, danvedo@hotmail.com, and mnogueira@famerp.br. Albert J. Auguste and Scott C. Weaver, Institute for Human Infections and Immunity and Department of Pathology, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX, E-mails: aj1augus@utmb.edu and sweaver@utmb.edu. Marcelo U. Ferreira and Monica da Silva-Nunes, Instituto de Ciências Biológicas/Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil, E-mails: muferrei@gmail.com and msnunes1@yahoo.com.br. Márcia A. Sperança, Rodrigo B. Suzuki, and Camila Juncansen, Universidade Federal do ABC, Santo André, São Paulo, Brazil, E-mails: speranca@yahoo.com, rbsuzuki@gmail.com, and camilacj@yahoo.com.br. João P. Araújo Jr., Universidade Estadual Paulista, Botucatu, São Paulo, Brazil, E-mail: jpessoa@ibb.unesp.br.

References

- 1.Figueiredo LT. Emergent arboviruses in Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2007;40:224–229. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822007000200016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coimbra TL, Santos CL, Suzuki A, Petrella SM, Bisordi I, Nagamori AH, Marti AT, Santos RN, Fialho DM, Lavigne S, Buzzar MR, Rocco IM. Mayaro virus: imported cases of human infection in Sao Paulo State, Brazil. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2007;49:221–224. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46652007000400005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silva-Nunes M, Malafronte Rdos S, Luz Bde A, Souza EA, Martins LC, Rodrigues SG, Chiang JO, Vasconcelos PF, Muniz PT, Ferreira MU. The Acre Project: the epidemiology of malaria and arthropod-borne virus infections in a rural Amazonian population. Cad Saude Publica. 2006;22:1325–1334. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2006000600021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tavares-Neto J, Freitas-Carvalho J, Nunes MR, Rocha G, Rodrigues SG, Damasceno E, Darub R, Viana S, Vasconcelos PF. Serologic survey for yellow fever and other arboviruses among inhabitants of Rio Branco, Brazil, before and three months after receiving the yellow fever 17D vaccine. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2004;37:1–6. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822004000100001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vasconcelos PF, Travassos da Rosa AP, Rodrigues SG, Travassos da Rosa ES, Degallier N, Travassos da Rosa JF. Inadequate management of natural ecosystem in the Brazilian Amazon region results in the emergence and reemergence of arboviruses. Cad Saude Publica. 2001;17((Suppl)):155–164. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2001000700025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vasconcelos PF, Travassos da Rosa AP, Pinheiro FP, Shope RE, Travassos da Rosa JF, Rodrigues SG, Dégallier N, Travassos da Rosa ES. Arboviruses pathogenic for man in Brazil. In: Travassos da Rosa AP, Vasconcelos PF, Travassos da Rosa JF, editors. An Overview of Arbovirology in Brazil and Neighbouring Countries. Belém: Evandro Chagas Institute; 1998. pp. 72–99. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pinheiro FP, Freitas RB, Travassos da Rosa JF, Gabbay YB, Mello WA, LeDuc JW. An outbreak of Mayaro virus disease in Belterra, Brazil. I. Clinical and virological findings. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1981;30:674–681. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1981.30.674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pinheiro FP, LeDuc JW. Mayaro virus disease. In: Monath TP, editor. The Arboviruses: Epidemiology and Ecology. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1988. pp. 137–50. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Theiler M, Downs WG. The Arthropod-Borne Viruses of Vertebrates. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Long KC, Ziegler SA, Thangamani S, Hausser NL, Kochel TJ, Higgs S, Tesh RB. Experimental transmission of Mayaro virus by Aedes aegypti. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011;85:750–757. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2011.11-0359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Travassos da Rosa, ATdR JF, Pinheiro FP, Vasconcelos PF. Arboviroses. In: de Leão RN, editor. Doenças Infecciosas e Parasitarias: Enfoque Amazônico. Belém: CEJUP; 1997. pp. 207–22. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson CR, Downs WG, Wattley GH, Ahin NW, Reese AA. Mayaro virus: a new human disease agent. II. Isolation from blood of patients in Trinidad, B.W.I. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1957;6:1012–1016. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1957.6.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schaeffer M, Gajdusek DC, Lema AB, Eichesewald H. Epidemic jungle fevers among Okinawan colonists in the Bolivian rain forest. I. Epidemiology. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1959;8:372–396. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1959.8.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forshey BM, Guevara C, Laguna-Torres VA, Cespedes M, Vargas J, Gianella A, Vallejo E, Madrid C, Aguayo N, Gotuzzo E, Suarez V, Morales AM, Beingolea L, Reyes N, Perez J, Negrete M, Rocha C, Morrison AC, Russell KL, Blair PJ, Olson JG, Kochel TJ. Group NFSW Arboviral etiologies of acute febrile illnesses in Western South America, 2000–2007. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4:e787. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Talarmin A, Chandler LJ, Kazamji M, de Thoisy B, Debon P, Lelarge J, Labeau B, Bourreau E, Vié JC, Shope RE, Sarthou J-L. Mayaro virus fever in French Guiana: isolation, identification and seroprevalence. Am Soc J Trop Med Hyg. 1981;59:452–456. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.59.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Halsey ES, Siles C, Guevara C, Vilcarromero S, Jhonston EJ, Ramal C, Aguilar PV, Ampuero JS. Mayaro virus infection, Amazon Basin region, Peru, 2010–2013. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:1839–1842. doi: 10.3201/eid1911.130777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Munoz M, Navarro JC. Mayaro: a re-emerging arbovirus in Venezuela and Latin America. Biomedica. 2012;32:286–302. doi: 10.1590/S0120-41572012000300017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Causey O, Maroja OM. Mayaro virus: a new human disease agente. III. Investigation of an epidemic of acute febrile illnes on the River Guama in Pará, Brazil, and isolation of Mayaro virus as a causative agent. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1957;6:1017–1023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mourao MP, Bastos Mde S, de Figueiredo RP, Gimaque JB, Galusso Edos S, Kramer VM, de Oliveira CM, Naveca FG, Figueiredo LT. Mayaro fever in the city of Manaus, Brazil, 2007–2008. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2012;12:42–46. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2011.0669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Powers AM, Aguilar PV, Chandler LJ, Brault AC, Meakins TA, Watts D, Russell KL, Olson J, Vasconcelos PF, Da Rosa AT, Weaver SC, Tesh RB. Genetic relationships among Mayaro and Una viruses suggest distinct patterns of transmission. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;75:461–469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.da Silva-Nunes M, de Souza VA, Pannuti CS, Speranca MA, Terzian AC, Nogueira ML, Yamamura AM, Freire MS, da Silva NS, Malafronte RS, Muniz PT, Vasconcelos HB, da Silva EV, Vasconcelos PF, Ferreira MU. Risk factors for dengue virus infection in rural Amazonia: population-based cross-sectional surveys. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;79:485–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Morais Bronzoni RV, Baleotti FG, Ribeiro Nogueira RM, Nunes M, Moraes Figueiredo LT. Duplex reverse transcription-PCR followed by nested PCR assays for detection and identification of Brazilian alphaviruses and flaviviruses. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:696–702. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.2.696-702.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Green MR, Sambrook J. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F. MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:754–755. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.8.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neumayr A, Gabriel M, Fritz J, Gunther S, Hatz C, Schmidt-Chanasit J, Blum J. Mayaro virus infection in traveler returning from Amazon Basin, northern Peru. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18:695–696. doi: 10.3201/eid1804.111717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Receveur MC, Grandadam M, Pistone T, Malvy D. Infection with Mayaro virus in a French traveler returning from the Amazon region, Brazil, January, 2010. Euro Surveill. 2010;15:19563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hassing RJ, Leparc-Goffart I, Blank SN, Thevarayan S, Tolou H, van Doornum G, van Genderen PJ. Imported Mayaro virus infection in The Netherlands. J Infect. 2010;61:343–345. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2010.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuniholm MH, Wolfe ND, Huang CY, Mpoudi-Ngole E, Tamoufe U, LeBreton M, Burke DS, Gubler DJ. Seroprevalence and distribution of Flaviviridae, Togaviridae, and Bunyaviridae arboviral infections in rural Cameroonian adults. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;74:1078–1083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]