Abstract

The objective of this study was to ascertain risk factors for complications (reactions or neuritis) in leprosy patients at the time of diagnosis in three leprosy-endemic countries. Newly diagnosed patients were enrolled in Brazil, the Philippines, and Nepal, and risk factors for reactions and neuritis were assessed using a case-control approach: “cases” were patients with these complications, and controls were patients without complications. Of 1,972 patients enrolled in this study, 22% had complications before treatment. Type 1 reaction was diagnosed in 13.7% of patients, neuritis alone in 6.9.%, and type 2 reaction in 1.4%. The frequency of these complications was higher in Nepal, in lepromatous patients, in males, and in adults versus children. Reactions and neuritis were seen in patients at diagnosis, before treatment was started. Reactions were seen in adults and children, even in patients with only a single lesion. Neuritis was often present without other signs of reaction. Reactions and neuritis were more likely to occur in lepromatous patients, and were more likely to be seen in adults than in children.

Introduction

“Reactions” are systemic inflammatory complications often presenting as medical emergencies during the course of treated or untreated leprosy, an infection that is otherwise remarkably indolent. Two major clinical types of leprosy reactions occur; together they may affect 30–50% of all leprosy patients.1–3 Because Mycobacterium leprae infect peripheral nerves, the inflammation associated with reactions often leads to severe nerve injury with the possibility of subsequent paralysis and deformity. These reactions appear to have different underlying immunologic mechanisms, but both are poorly understood and the factors that initiate them are completely unknown.4

Endocrine influences in the initiation of reactions have long been proposed.5 Reports have indicated that leprosy reactions may be affected by pregnancy and lactation6,7 and puberty,5 for example. In lepromatous males, insufficiency of testicular hormone secretion has been documented,8,9 resulting in gynecomastia and impotence. Interaction between the immune and endocrine systems is well established,10 and recent reports have suggested the interplay between endocrine hormones and cytokines in leprosy,11,12 offering a possible mechanistic basis for the potential influence of hormones on immunity in leprosy. The possibility that hormonal influences on immunity may initiate or modulate acute leprosy reactions is of great clinical importance, because these reactions are responsible for much of the morbidity and nerve injury in this disease.

This report describes the methodological issues and the baseline data of a multicenter study assessing clinical and endocrine factors for leprosy reactions in three endemic countries. We compared the demographic and clinical characteristics in newly detected leprosy patients in three countries. The potential risk factors for leprosy reactions and neuritis at the time of diagnosis were assessed using a case-control approach.

Methods

Study design and setting.

This study was designed as a multicenter cohort. Baseline data from all patients enrolled were analyzed. Comparisons were made between patients with complications (T1R, T2R, or neuritis) and patients who did not have these complications using a case-control approach.

Patients were enrolled at four clinics in three endemic countries: in Brazil, at the Reference Center for Diagnosis and Treatment, in Goiania-Central Brazil (population 1.2 million, leprosy prevalence 6.5/100,000), and at the Fundacao Alfredo da Matta in Manaus-North Region (pop. 1.6 million, prevalence of 5.8/100,000); in the Republic of the Philippines at the Eversley Childs Sanitarium, Leonard Wood Memorial, Cebu (pop. 4 million, leprosy prevalence 0.34/100,000); and in Nepal at Lalgadh Leprosy Services Center, Lalgadh (three Terai districts pop. 2.0 million, prevalence 13.4/100,000). These sites were selected based on substantial patient recruitment, established local expertise and experience in diagnosis, classification, and management of leprosy by physicians, and experience in clinical–epidemiological research studies. The field study was conducted between the years 2003 and 2008.

Eligibility criteria.

All newly diagnosed leprosy patients were eligible for the study, regardless of age, gender, or other illness. The exclusion criteria were treatment with corticosteroids before enrollment, or anticipated lack of follow-up, usually caused by distance of residence from the clinic.

Leprosy classification and diagnosis of reactions and neuritis.

Leprosy classification was performed using the Ridley-Jopling scale,13 and the definition of reactions followed standard criteria.14,15 A diagnostic skin biopsy was obtained from each patient agreeing to this procedure; biopsies were evaluated by an experienced pathologist. When skin biopsies were not available, skin smears were used to assist in classification. A type 1 reaction (T1R) was diagnosed when a patient had erythema and edema of the skin lesion, sometimes accompanied by edema of the hands, feet, and face. A type 2 reaction (T2R) was diagnosed by the onset of crops of tender erythematous lesions anywhere on the body. Either reaction may be accompanied by neuritis, malaise, and fever. The skin signs were obligatory; the nerve and systemic signs optional. For this initial data analysis, neuritis was defined as the presence of pain, tenderness, or loss of function at the time of diagnosis or within 3 months before diagnosis.

Data collection.

All clinics used a standard protocol to document the demographic characteristics, weight and height of patients, aspects of endocrine history, date of last menstrual period, gestational history, and current and past co-morbidity. The physical examination was performed by experienced doctors, and included a chart to draw the lesions and a special form to report results of sensory and motor function tests.

Case-control approach.

Cases were newly detected leprosy patients diagnosed with T1R or T2R or neuritis at baseline. Controls were newly detected leprosy patients who did not have T1R or T2R or neuritis at the time of initial diagnosis.

For the baseline data on all patients enrolled, three case-control approaches were performed: 1) combining all patients with acute leprosy events (T1R, T2R, or neuritis) as cases compared with patients without acute events as controls; 2) selecting patients with T1R as cases versus controls; 3) selecting patients with neuritis as compared with controls. Type 2 reaction was not analyzed separately because of the low frequency of this event at baseline. We combined data from patients recruited in both cities in Brazil (Goiania and Manaus). Leprosy clinical forms were aggregated into paucibacillary (indeterminate [I], polar tuberculoid [TT], and borderline tuberculoid [BT]) and multibacillary (mid-borderline [BB], borderline lepromatous [BL], and polar lepromatous [LL]) types.

Data analysis.

Descriptive statistics were applied to the patient's characteristics. Body mass index (BMI) levels was calculated as kg/m2 for patients ≥ 18 years of age, and classified as the standard criteria: < 18.49, underweight; 18.50–25.00, normal; 25.01–30.00, overweight; > 30.00, obese.16 Clinical forms classified as indeterminate, pure neural, and single lesion types were combined and designated indeterminate for purposes of analysis.

The number of days since the last menstrual period to the initial visit was calculated for all fertile women (13–45 years of age), who were not pregnant or lactating at baseline. This period was compared for women with or without reactions/neuritis. When the last menstrual period was > 40 days before initial medical visit the record was excluded.

Exploratory data analysis, including box-plot, medians, and standard deviation were calculated for the assessment of the time since reaction. The χ2 tests were applied to compare differences of proportions of reaction types among sites.

Means and medians were calculated to summarize continuous variables. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the post hoc test (Tamhane's test for unequal variance assumption) were used to identify homogeneous subsets for the variables age and BMI among the sites. The P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical tests of hypotheses are two-sided.

Case-control analysis.

We applied unconditional logistic regression to assess risk factors associated with the different types of events at baseline. Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence levels for risk factors were estimated from their respective model coefficients in the multivariate logistic regression model. Only risk factors with P values < 0.10 in univariate analyses were included in the final multivariate models. All statistical analyses and graphics were produced with SPSS (version 18; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Sample size.

For the case-control approaches, the following parameters were used to assess the statistical power and confidence levels: 1,531 controls and 35% of exposure among the control group. For the first approach, the sample size of 434 cases (T1R or T2R or neuritis) compared with controls, was sufficient to estimate an OR ≥ 1.5 with 95% confidence and power levels. For the second analysis, the sample size of 270 cases (T1R) compared with controls were sufficient to estimate an OR ≥ 1.5 with 95% confidence level and 80% power. For the third case-control approach, the sample size of 136 cases of neuritis compared with controls were sufficient to estimate an OR ≥ 1.8 with 95% confidence level and 80% power. We used all controls for the analyses to achieve optimum power to detect associations.

Ethical considerations.

The study was approved by human studies committees in each country. Consent forms were prepared in the patient's own language. Patients were registered in the study after obtaining written informed consent (or the guardian of the patients when children or adolescents). The study was reviewed and approved by the authorized ethical committee at each site.†

Results

Patients' characteristics.

A total of 1,972 newly untreated leprosy patients were recruited; 53.3% were from Nepal, 33.4% from two Brazilian sites, and 13.3% from the Philippines. In all sites the majority of the cases were detected in patients > 15 years of age. There was a statistically significant difference of mean age by settings using the ANOVA approach for multiple comparisons, and the post hoc test detected that the participants recruited in Goiania were older compared with the other sites, which represented a homogenous subset. There was a predominance of male patients in all sites and the ratio between males and females was more than two in the Asian countries. The nutritional status was in the normal or overweight range for the majority of the patients recruited in Brazil. In contrast, 50.5% of patients recruited in Nepal were considered underweight with < 3% of patients considered overweight. There were three homogeneous subgroups considering the BMI variable; Nepal had the lowest mean BMI (18.8; SD = 2.7); followed by Cebu 22.3 (SD = 3.5); and the third subgroup comprised the two Brazilian Goiania and Manaus with 24.6 (SD = 4.4) and 25.6 (SD = 4.8), respectively. In Brazil, 59.8% and 34.5% of the patients were classified as BT cases, in the Central-West region and North region, respectively. In the Philippines, BL and LL types were the predominant classifications (43.3% and 27.4%, respectively). In Nepal the patients classified BT were 44.4% of the recruited cases, followed by 18.6% with the Indeterminate form and 14.6% were TT. Overall, indeterminate forms represented 12% of the participants (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of leprosy patients at baseline by recruitment sites

| Variables | Participants | Brazil | Philippines | Nepal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goiania | Manaus | Cebu | Lalgadh | ||

| N = 1972 (%) | N = 351 (%) | N = 307 (%) | N = 263 (%) | N = 1051 (%) | |

| Age (years) | |||||

| 0–14 | 163 (8.3) | 9 (2.6) | 23 (7.5) | 19 (7.2) | 112 (10.7) |

| 15–29 | 641 (32.5) | 110 (31.3) | 119 (38.8) | 110 (41.8) | 302 (28.7) |

| 30–44 | 567 (28.7) | 97 (27.6) | 73 (23.8) | 75 (28.5) | 322 (30.6) |

| 45–59 | 417 (21.1) | 93 (26.5) | 60 (19.5) | 41 (15.6) | 223 (21.2) |

| ≥ 60 | 184 (9.3) | 42 (12.0) | 32 (10.4) | 18 (6.8) | 92 (8.8) |

| Mean age (SD) | 35.5 (16.0) | 39.3 (16.3) | 35.2 (16.7) | 33.1 (14.8) | 34.8 (15.8) |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 1299 (65.9) | 201 (57.3) | 194 (63.2) | 183 (69.6) | 721 (68.6) |

| Female | 673 (34.1) | 150 (42.7) | 113 (36.8) | 80 (30.4) | 330 (31.4) |

| Body mass index* | |||||

| Underweight | 421 (21.3) | 9 (5.8) | 6 (2.5) | 20 (9.3) | 386 (50.5) |

| Normal | 706 (35.8) | 79 (50.6) | 115 (47.1) | 154 (71.6) | 358 (46.9) |

| Overweight | 191 (9.9) | 51 (29.8) | 92 (37.7) | 34 (15.8) | 15 (2.0) |

| Obese | 61 (3.1) | 19 (11.1) | 31 (12.7) | 7 (3.3) | 5 (0.7) |

| Clinical Form† | |||||

| I | 237 (12.0) | 7 (2.0) | 27(8.8) | 8 (3.0) | 195 (18.6) |

| TT | 241 (12.2) | 20 (5.7) | 67 (21.8) | 1 (0.4) | 153 (14.6) |

| BT | 841 (42.6) | 210 (59.8) | 106 (34.5) | 58 (22.1) | 467 (44.4) |

| BB | 165 (8.4) | 51 (14.5) | 41 (13.8) | 10 (3.8) | 63 (6.0) |

| BL | 253 (12.8) | 32 (9.1) | 37 (12.1) | 114 (43.3) | 70 (6.7) |

| LL | 235 (12.0) | 31 (8.1) | 29 (9.4) | 72 (27.4) | 103 (9.8) |

| Reactions‡ | |||||

| Type 1 | 271 (13.7) | 28 (8.0) | 32 (10.4) | 28 (10.6) | 183 (17.4) |

| Type 2 | 28 (1.4) | 6 (1.7) | − | 8 (3.0) | 14 (1.3) |

| Neuritis | 136 (6.9) | 17 (4.8) | 15 (4.9) | 5 (1.9) | 100 (9.5) |

Body Mass Index (BMI) (kg/m2) for ≥ 18 years of age. Underweight < 18.49; Normal weight = 18.50 thru 25.00; Overweight = 25.01 thru 30.00; Obese = 30.01 thru highest.

Sixty-five patients were classified as indeterminate (Goiania = 3; Manaus = 20; Cebu = 8; Lalgadh = 34); 59 patients were classified as Pure Neural (Goiania = 4; Manaus = 6; Lalgadh = 49); 113 patients were classified as single lesion (Manaus = 1; Lalgadh = 112).

Reaction at onset and diagnosis.

I = indeterminate; TT = polar tuberculoid; BT = borderline tuberculoid; BB = mid-borderline; BL = borderline lepromatous; LL = polar lepromatous.

Frequency of reactions and neuritis.

At baseline 435 (22.1%) out of 1,972 patients had T1R, T2R, or neuritis. Overall, the most frequent event was T1R (13.7%) followed by neuritis with no signs of reactions (6.9%) and T2R (1.4%). These complications were observed in about 15% of all patients in Brazil and in the Philippines, statistically lower than the percentage (∼30%) found in Nepal (χ2 = 49.7; P < 0.001). Among those who had reactions at the time of diagnosis, T1R was diagnosed in 17.4% of new patients in Nepal, ∼10% in Manaus, and Cebu and 8% in Goiania. The frequency of T2R at the time of diagnosis varied from 0% to 3% (Table 1).

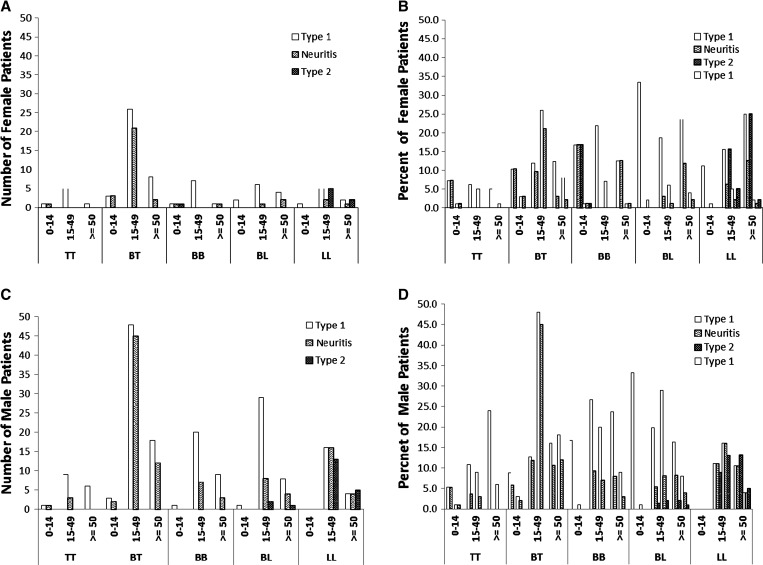

Type 1 reaction was observed in 14.6% of males and 12.1% of females, and T2R in 1.6% and 1.7%, respectively. Figure 1 shows the occurrence of events by age group, by clinical forms, and sex. Of 614 females, 73 (10.8%) had T1R, the most frequent event in all age groups, followed by neuritis (5%). T2R were present in only 8 out of 614 newly diagnosed females (1%), in BB, BL, and LL types (Figure 1A and B). Of 1,186 males 190 (16.0%) presented T1R at the time of diagnosis, followed by 8.8% with neuritis and 1.7% of T2R (Figure 1C and D). Simultaneous occurrence of both reactions was recorded in 4 patients (0.9%).

Figure 1.

Frequency of leprosy reactions or neuritis in females (A and B) and males (C and D) at time of diagnosis, by age group and leprosy classification. Open bars, T1R; Solid bars, T2R; Hatched bars, Neuritis without other sign of reaction. Leprosy classifications: I = indeterminate; TT = polar tuberculoid; BT = borderline tuberculoid; BB = mid-borderline; BL = borderline lepromatous; LL = polar lepromatous.

Risk factors assessment.

In the univariate analysis, patients recruited in Nepal had a higher risk of developing any adverse event (OR crude = 2.25; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.73–2.93) when compared with patients recruited in the Brazilian sites males were more prone to develop reactions or neuritis than females (OR crude = 1.49; 95% CI 1.17–1.90). There was an upward trend to the occurrence of any adverse event in older age groups. The risk of reaction or neuritis associated with nutritional status was greater for the underweight group (OR crude = 1.09; 0.82–1.46) when compared with the normal BMI category. However, difference in the nutritional status was not statistically significantly associated with the cases with reactions or neuritis compared with controls and therefore this variable was not included in the multivariate models (data not shown).

In multivariate analysis, patients recruited in Nepal had 2-fold increased risk of having any event (OR adjusted = 2.62; 95% CI 1.81–3.79) compared with patients from Brazilian settings, after adjusting for the potential confounders (Table 2). Male patients were more prone to have reactions (OR adjusted = 1.33; 95% CI 1.05–1.79) compared with females. A trend was observed between increasing age and the development of complications (reactions or neuritis). The multibacillary (MB) forms were more likely to be independently associated with reactions or neuritis combined.

Table 2.

Association between risk factors for all events at time of diagnosis*

| Variables | Cases (N = 435) | Controls (N = 1531) | OR crude (95% CI) | OR adjusted (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sites | ||||

| Brazil | 97 | 555 | 1 | 1 |

| Philippines | 41 | 222 | 1.06 (0.70–1.74) | 1.39 (0.69–1.54) |

| Nepal | 297 | 754 | 2.25 (1.73–2.93) | 2.62 (1.81–3.79) |

| Sex | ||||

| Females | 119 | 551 | 1 | 1 |

| Males | 316 | 980 | 1.49 (1.17–1.90) | 1.33 (1.05–1.79) |

| Age years | ||||

| 0–14 | 23 | 140 | 1 | 1 |

| 15–29 | 124 | 514 | 1.47 (0.89–2.45) | 0.87 (0.57–1.32) |

| 30–44 | 139 | 427 | 1.98 (1.20–3.30) | 0.92 (0.62–1.39) |

| 45–59 | 106 | 311 | 2.07 (1.24–3.50) | 1.14 (0.76–1.71) |

| ≥ 60 | 43 | 139 | 1.88 (1.04–3.42) | 1.76 (0.99–3.13) |

| Clinical types | ||||

| PB | 245 | 1073 | 1 | 1 |

| MB | 190 | 458 | 1.86 (1.39–2.48) | 2.30 (1.72–3.07) |

All events include T1R, T2R, and neuritis.

Adjusted odds ratio (OR) estimated by multivariate analysis.

CI = confidence interval; PB = paucibacillary; MB = multibacillary.

The association between risk factors for T1Rs at the time of diagnoses is shown in Table 3. Older age groups were only marginally associated with T1R or neuritis.

Table 3.

Association between risk factors for Type 1 reactions at time of diagnosis*

| Variables | Cases (N = 271) | Controls (N = 1531) | OR crude (95% CI) | OR adjusted (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sites | ||||

| Brazil | 60 | 555 | 1 | 1 |

| Philippines | 28 | 222 | 1.17 (0.73–1.88) | 1.09 (0.64–1.75) |

| Nepal | 183 | 754 | 2.24 (1.64–3.07) | 2.58 (1.88–3.51) |

| Sex | ||||

| Females | 81 | 551 | 1 | 1 |

| Males | 190 | 980 | 1.31 (1.01–1.74) | 1.14 (0.85–1.51) |

| Age years | ||||

| 0–14 | 17 | 140 | 1 | 1 |

| 15–29 | 76 | 514 | 1.22 (0.70–2.13) | 2.29 (0.73–2.28) |

| 30–44 | 85 | 427 | 1.63 (0.94–2.86) | 1.64 (0.93–2.99) |

| 45–59 | 64 | 311 | 1.69 (0.96–3.00) | 1.72 (0.96–3.08) |

| ≥ 60 | 29 | 139 | 1.72 (0.90–3.27) | 1.67 (0.86–3.24) |

| Clinical types | ||||

| PB | 154 | 1073 | 1 | 1 |

| MB | 117 | 458 | 1.78 (1.36–2.32) | 2.14 (1.52–3.02) |

Adjusted odds ratio (OR) estimated by multivariate analysis.

CI = confidence interval; PB = paucibacillary; MB = multibacillary.

The risk of neuritis at time of diagnosis was higher in Nepal (OR adjusted = 2.5, 95% CI 1.64–3.83) compared with Brazil (Table 4). The risk of neuritis was greater in males than females, and greater in MB than paucibacillary (PB) cases (OR adjusted = 1.58, 95% CI 1.05–2.37).

Table 4.

Association between risk factors for neuritis at time of diagnosis

| Variables | Cases (N = 136) | Controls (N = 1531) | OR crude (95% CI) | OR adjusted (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sites | ||||

| Brazil | 32 | 555 | 1 | 1 |

| Philippines | 5 | 222 | 0.39 (0.15–1.02) | 0.34 (0.13–0.87) |

| Nepal | 99 | 754 | 2.27 (1.51–3.45) | 2.50 (1.64–3.83) |

| Sex | ||||

| Females | 30 | 551 | 1 | 1 |

| Males | 106 | 980 | 1.99 (1.31–3.02) | 1.72 (1.12–2.63) |

| Age years | ||||

| 0–14 | 6 | 140 | 1 | 1 |

| 15–29 | 43 | 514 | 1.95 (0.81–4.67) | 2.08 (0.85–5.06) |

| 30–44 | 43 | 427 | 2.35 (0.98–5.65) | 2.19 (0.90–5.32) |

| 45–59 | 35 | 311 | 2.62 (1.08–6.37) | 2.52 (1.02–6.23) |

| ≥ 60 | 9 | 139 | 1.51 (0.52–4.37) | 1.32 (0.45–3.87) |

| Clinical types | ||||

| PB | 92 | 1073 | 1 | 1 |

| MB | 44 | 458 | 1.12 (0.77–1.63) | 1.58 (1.05–2.37) |

Adjusted odds ratio (OR) estimated by multivariate analysis.

CI = confidence interval; PB = paucibacillary; MB = multibacillary.

Reactions related to the menstrual cycle.

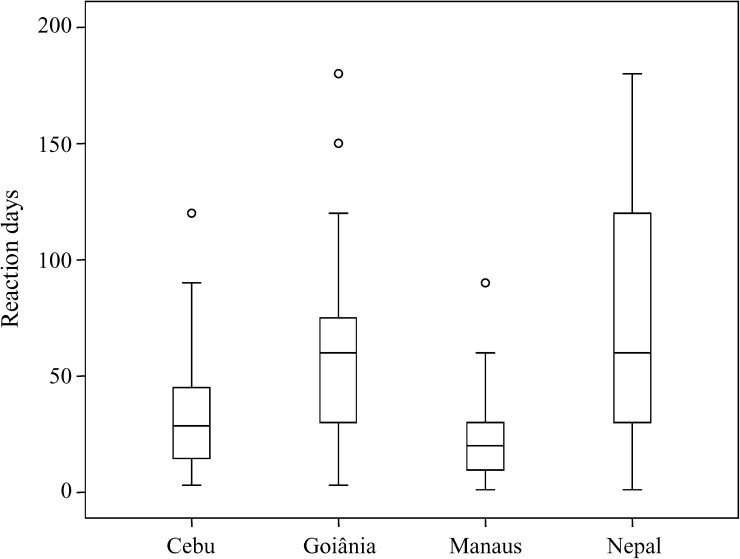

Because the menstrual cycle reflects well-established fluctuations of gonadotrophic hormones, we attempted to determine whether the occurrence of reactions could be associated with specific phases of this cycle. Of the 673 women about 60% were during reproductive age, with similar frequencies among sites. The majority of these women did not present signs of reactions at the onset of the diagnosis (Table 5). The box-plot distribution of the length of time between the last menstrual period and reaction is shown in Figure 2 , stratified by recruitment site.

Table 5.

Occurrence of reactions or neuritis at baseline according to days since the last menstrual period among fertile women, by sites

| Women | Participants | Brazil | Philippines | Nepal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goiania | Manaus | Cebu | Lalgadh | ||

| Fertile*/total (%) | 402/673 (59.7) | 94/150 (62.7) | 61/113 (54.0) | 53/80 (66.2) | 194/330 (58.8) |

| No reaction/fertile† (%) | 283/402 (70.4) | 79/94 (84.0) | 49/61 (80.3) | 42/53 (79.2) | 113/194 (58.2) |

| Range–days | 0–39 | 0–33 | 0–31 | 1–33 | 1–39 |

| Median–days | 14 | 13 | 17 | 14 | 13 |

| Reaction/fertile† (%) | 51/402 (12.7) | 6/94 (6.4) | 5/61 (8.2) | 6/53 (11.3) | 34/194 (17.5) |

| Range–days | 0–35 | 1–30 | 10–29 | 7–26 | 0–35 |

| Median–days | 16 | 6.5 | 19 | 16.5 | 17 |

Fertile: 13–45 years old, not pregnant and with last menstrual period (LMP) date.

Women age 13–45 years, not pregnant, LMP ≤ 40 days.

Figure 2.

Duration (days) of reaction symptoms before clinic visit at the time of leprosy diagnosis at each site. In box plots, boxes encompass 25th and 75th percentiles of each variable distribution. Black lines within boxes indicate median values.

Discussion

This multicenter study of nearly 2,000 patients provides a contemporary picture of the prevalence of reactions and neuritis in leprosy in four clinics in three widely separated endemic countries, and enables comparisons between them. Data collection for this study separated the occurrence of neuritis alone from that occurring during reactions. The evidence here indicates that neuritis is a complication of leprosy that is often not associated with the other clinical signs and symptoms of reaction, although other studies have clearly shown that neuritis does often complicate reactions, also.15,17,18

Because both T1R and T2R were observed at the initial diagnostic visit, before the start of treatment (in 13.7% and 1.4% of patients, respectively), it is evident that leprosy reactions are not necessarily the result of treatment. These findings are in agreement with the results of a large retrospective study in India ∼10 years ago3 in which 30.9% of patients had a reaction at the time of the first visit, but indicate a greater prevalence of reaction at the time of diagnosis than observed in Ethiopia (9.8%) in the late 1980s.1

Although the factors that may trigger T1R are not known, recent studies19,20 have suggested some genetic associations with a higher risk of leprosy reactions. If there is a genetic susceptibility to T1R or T2R, this risk may then be expected to apply before treatment has begun.

Reactions and neuritis were observed in children (< 14 years of age), both male and female, with all forms of leprosy (Figure 1A and B). However, children had the lowest incidence of these complications and, as noted in Table 3, the risk of reaction appeared to be correlated with increasing age. This is consistent with prior reports of the association of T1R with older age.21 It is notable that T1R and neuritis were observed in a substantial number of children with indeterminate or single-lesion disease. Previous studies have also observed T1R in single-lesion disease.22 Although these are generally considered to be milder forms of leprosy, and short treatment regimens have been encouraged by some,16 the presence of these complications during multidrug therapy is a reminder that even early leprosy is a serious disease and must not be underestimated.

Among all LL and BL patients in this study, T2R was much less frequent than T1R, in contrast to the previous findings in Thailand in the 1980s in which T2R was slightly more prevalent than T1R (25% and 20%, respectively) in lepromatous patients.2 This may be influenced by the ethnic group studied; among Ethiopian patients, also studied in the late 1980s, T2R represented only about 10% of all reactions among MB patients.1 However, in this study of patients in South American and Asian populations, the overall prevalence of reactions is remarkably consistent. The T2R may also have been underestimated in this study as a result of the exclusion of patients who had received prednisone at local health centers prior to the diagnosis of leprosy. Although many patients in this study were underweight, nutritional status was not a risk factor for the development of reactions or neuritis.

To test the hypothesis that endocrine changes might precipitate reactions, we asked whether the timing of reactions in women is related to the different phases of the menstrual cycle. But such an association could not be shown with the study design and methods used. A substantial number/percentage of women did not present to the clinic in a timely manner after the onset of reaction symptoms and the resulting data collected included time spans of more than a month for both the history of onset of reaction symptoms and the date of last menstrual period. Additional findings concerning the possibility of an association between reactions and levels of circulating hormones will be presented in a future report.

Conclusions

Reactions and neuritis (without reaction) occurred in all age groups and all types of leprosy, with an overall frequency that was similar in different parts of the world. Neuritis, a complication of leprosy that may occur during reactions, often was not associated with the other clinical signs and symptoms of reaction in this study. In all populations studied, T1R greatly outnumbered T2R. Although children had the lowest incidence of reactions and neuritis, these complications occurred in many children with single-lesion disease. The risk of reaction appeared to be correlated with increasing age.

In a multivariate analysis, nutritional status was not a risk factor for the development of reactions or neuritis. No association was identified between the timing of reactions or neuritis and phases of the menstrual cycle; long delays in seeking medical attention and uncertainties about the time involved made it impossible to reach conclusions about this with certainty.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Victoria Balagon, Cebu Skin Clinic, and LWM's technical and Support Staff for technical and clerical assistance; to Bimela Ojha, Director of Leprosy Services, Ministry of Health, Nepal; Graeme Clugston and Jeevan Thapa at Lalgath Leprosy Services Center; and Kamal Shrestha, Nepal Leprosy Trust; and to Noemia Teixeria de Siqueitra Filha for assistance in preparing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Financial support: We are grateful to the American Leprosy Missions for financial support. Support was also received from the Brazilian government (CNPq grant 306489/2010-4 to Celina M. T. Martelli; CNPq grant 310582/2011-3 to Mariane M. A. Stefani).

Authors' addresses: David M. Scollard, National Hansens Disease Programs, Clinical Branch, Baton Rouge, LA, E-mail: dscollard@hrsa.gov. Celina M. T. Martelli, Universidade Federal de Goiás, Instituto de Patologia Tropical e Saúde Publica, Departamento de Saúde Coletiva, Goiania, Goiás, Brazil, E-mail: celina@pq.cnpq.br. Mariane M. A. Stefani, Federal University of Goiás, Institute of Tropical Pathology and Public Health, Goiás, Brazil, and Immunology, Goiania, Goias, Brazil, E-mail: mariane.stefani@pq.cnpq.br. Maria de Fatima Maroja, Fundação de Dermatologia Tropical Alfredo da Matta, Dermatology, Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil, E-mail: dahw.am@click21.com.br. Laarni Villahermosa and Fe Pardillo, Leonard Wood Memorial Center for Leprosy Research, Dermatology, Cebu, The Philippines, E-mails: lgvmed@hotmail.com and pardillo_feeleanor@yahoo.com. Krishna B. Tamang, Lalgadh Leprosy Hospital and Services Center, Surgery, Lalgadh, Dhanusha District, Nepal, E-mail: tsuman@mos.com.np.

In the United States, by the IRB of Tulane University (S 0430); in Brazil, by the Ethical Committees of the Federal University of Goias (CEPMHA/HC/ UFG No 102/2003) and the Fundacao Alfredo da Matta in Manaus (CEP/FUAM no. 006/2004); in Cebu by the Institutional Regulator Board of the Leonard Wood Memorial; and in Nepal, by the Ministry of Health.

References

- 1.Becx-Bleumink M, Berhe D. Occurrence of reactions, their diagnosis and management in leprosy patients treated with multidrug therapy; experience in the leprosy control program of the All Africa Leprosy and Rehabilitation Training Center (ALERT) in Ethiopia. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1992;60:173–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scollard DM, Smith T, Bhoopat L, Theetranont C, Rangdaeng S, Morens DM. Epidemiologic characteristics of leprosy reactions. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1994;62:559–567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumar B, Dogra S, Kaur I. Epidemiological characteristics of leprosy reactions: 15 years experience from north India. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 2004;72:125–133. doi: 10.1489/1544-581X(2004)072<0125:ECOLRY>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scollard DM, Adams LB, Gillis TP, Krahenbuhl JL, Truman RW, Williams DL. The continuing challenges of leprosy. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:338–381. doi: 10.1128/CMR.19.2.338-381.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davey TF, Schenck RR. The endocrines in leprosy. In: Cochrane R. G., Davey T.F., editors. Leprosy in Theory and Practice. Bristol, UK: John Wright and Sons, Ltd.; 1964. p. 198. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duncan ME. An historical and clinical review of the interaction of leprosy and pregnancy: a cycle to be broken. Soc Sci Med. 1993;37:457–472. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90281-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saunderson P, Gebre S, Byass P. Reversal reactions in the skin lesions of AMFES patients: incidence and risk factors. Lepr Rev. 2000;71:309–317. doi: 10.5935/0305-7518.20000034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dash RJ, Samuel E, Kaur S, Datta BN, Rastogi GK. Evaluation of male gonadal function in leprosy. Horm Metab Res. 1978;10:362. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1095837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saporta L, Yuksel A. Androgenic status in patients with lepromatous leprosy. Br J Urol. 1994;74:221–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1994.tb16590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chrousos GP. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and immune-mediated inflammation. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1351–1362. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505183322008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leal AM, Magalhaes PK, Souza CS, Foss NT. Pituitary-gonadal hormones and interleukin patterns in leprosy. Trop Med Int Health. 2006;11:1416–1421. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leal AM, Foss NT. Endocrine dysfunction in leprosy. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;28:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s10096-008-0576-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ridley DS, Jopling WH. Classification of leprosy according to immunity: a five-group system. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1966;34:255–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lockwood D, Scollard DM. Report of workshop on nerve damage and reactions. Int J Lepr. 1999;67:6–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saunderson P, Gebre S, Desta K, Byass P, Lockwood DN. The pattern of leprosy-related neuropathy in the AMFES patients in Ethiopia: definitions, incidence, risk factors and outcome. Lepr Rev. 2000;71:285–308. doi: 10.5935/0305-7518.20000033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.WHO . Physical Status: The Use and Interpretation of Anthropometry. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lockwood DN, Sinha HH. Pregnancy and leprosy: a comprehensive literature review. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1999;67:6–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Brakel WH, Nicholls PG, Das L, Barkataki P, Suneetha SK, Jadhav RS, Maddali P, Lockwood DN, Wilder-Smith E, Desikan KV. The INFIR Cohort Study: investigating prediction, detection and pathogenesis of neuropathy and reactions in leprosy. Methods and baseline results of a cohort of multibacillary leprosy patients in north India. Lepr Rev. 2005;76:14–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sousa AL, Fava VM, Sampaio LH, Martelli CM, Costa MB, Mira MT, Stefani MM. Genetic and immunological evidence implicates interleukin 6 as a susceptibility gene for leprosy type 2 reaction. J Infect Dis. 2012;205:1417–1424. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Macdonald M, Berrington WR, Misch EA, Ranjit C, Siddiqui MR, Kaplan G, Hawn TR. Association of TNF, MBL, and VDR polymorphisms with leprosy phenotypes. Hum Immunol. 2010;71:992–998. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ranque B, Nguyen VT, Vu HT, Nguyen TH, Nguyen NB, Pham XK, Schurr E, Abel L, Alcaïs A. Age is an important risk factor for onset and sequelae of reversal reactions in Vietnamese patients with leprosy. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:33–40. doi: 10.1086/509923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sousa AL, Stefani MM, Pereira GA, Costa MB, Rebello PF, Gomes MK, Narahashi K, Gillis TP, Krahenbuhl JL, Martelli CM. Mycobacterium leprae DNA associated with type 1 reactions in single lesion paucibacillary leprosy treated with single dose rifampin, ofloxacin, and minocycline. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;77:829–833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]