Abstract

Buruli ulcer (BU) is an infectious skin disease that occurs mainly in West and Central Africa. It can lead to severe disability and stigma because of scarring and contractures. Effective treatment with antibiotics is available, but patients often report to the hospital too late to prevent surgery and the disabling consequences of the disease. In a highly endemic district in Ghana, intensified public health efforts, mainly revolving around training and motivating community-based surveillance volunteers (CBSVs), were implemented. As a result, 70% of cases were reported in the earliest—World Health Organization category I—stage of the disease, potentially minimizing the need for surgery. CBSVs referred more cases in total and more cases in the early stages of the disease than any other source. CBSVs are an important resource in the early detection of BU.

Buruli ulcer (BU) is a neglected tropical infectious skin disease caused by Mycobacterium ulcerans that is mainly endemic in West and Central Africa. BU typically starts with a small nodule that eventually ulcerates,1 and it often affects people in remote rural areas with limited access to healthcare. Here, the disease is perceived to be caused by witchcraft or a curse, and patients often resort to traditional treatment and report to the health facility late.2,3 The currently recommended treatment of 8 weeks of streptomycin and rifampicin is highly effective in resolving the infection,4 but with late presentation, most ulcers require surgery and prolonged hospitalization and have a higher risk of contractures and disability.5,6

A relevant measure of early reporting is the size of the lesion, which is reflected by the World Health Organization (WHO) categorization system for BU. In this system, a category I lesion is below 5 cm in cross-sectional diameter, a category II lesion is between 5 and 15 cm in diameter, and a category III lesion is larger than 15 cm in diameter or involving critical sites (e.g., the eye or genitals). Currently, only 32% of BU cases in Africa report to the hospital with a category I lesion (i.e., in the earliest stage of the disease).7 Late reporting has consequences for subsequent management. In three recent large case series, between 25% and 72% of patients required surgery in addition to drug treatment,8–10 with the size of the lesion at presentation being the major risk factor, and in one study, 30% of patients were hospitalized for the full duration of their treatment.9

Early detection of cases seems to be of vital importance and could, together with standardized drug treatment, drastically reduce the need for hospitalization and surgery. There are indications that community-based surveillance volunteers (CBSVs) can be effective in the early referral of BU cases,11 but solid evidence is lacking.12 Here, we report on the early detection activities of the BU Clinic in Agogo in the Ashanti region of Ghana, where recent advances in diagnosis and treatment of BU have been implemented and combined with rigorous public health efforts aimed at early detection and decentralized care.

Agogo, where the Agogo Presbyterian Hospital and the BU Clinic are based, is a relatively affluent town in the Ashanti region of Ghana. The endemic communities in its catchment area, however, are remote rural farming communities; they are characterized by high levels of poverty and illiteracy, and they do not have access to running water or electricity.

Two main methods were used for early detection of BU cases. First, BU team members joined outreach activities of the National Immunization Program and visited a different community each month, mainly targeting schools. In addition, the BU team visited each endemic community in the evening one time per year. During these evenings, a presentation was given about the disease, a WHO documentaries on BU was shown, and community members were screened for the disease.

Second, a network of 44 CBSVs was established, with one volunteer for each community in the catchment area of Agogo Presbyterian Hospital. The CBSVs are usually not selected by the health authorities but nominated by opinion leaders in their communities on the basis of such perceived traits as interest in the disease, being proactive and being knowledgeable in general. There are no formal criteria, but all CBSVs are literate; however, none of them had any previous training or experience in healthcare.

The CBSVs come to the hospital for training by the BU team approximately one time every 3 months. CBSVs are encouraged to do home visits, actively screen community members for BU in schools, churches, and mosques, and monitor treatment compliance of BU patients receiving medication. Over the years, the CBSVs were equipped with bicycles and mobile phones to facilitate transportation and communication.

CBSVs transportation costs (approximately US$1.50) are reimbursed when they accompany a patient to the hospital, and for each case that is confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), an incentive of approximately US$3.00 is given.

Tissue swabs or fine-needle aspirates are sent for diagnostic confirmation by PCR to a reference laboratory 80 km away in Kumasi, the regional capital, and the results come back within 1 week. After diagnosed, the patient is counseled and given a 14-day supply of rifampicin and streptomycin. Drugs and dressing materials are supplied by Ghana's National Buruli Ulcer Control Program and provided free of charge. Streptomycin administration by intramuscular injection and dressing take place in health centers in the communities, and patients come for review to the hospital one time every 2 weeks.

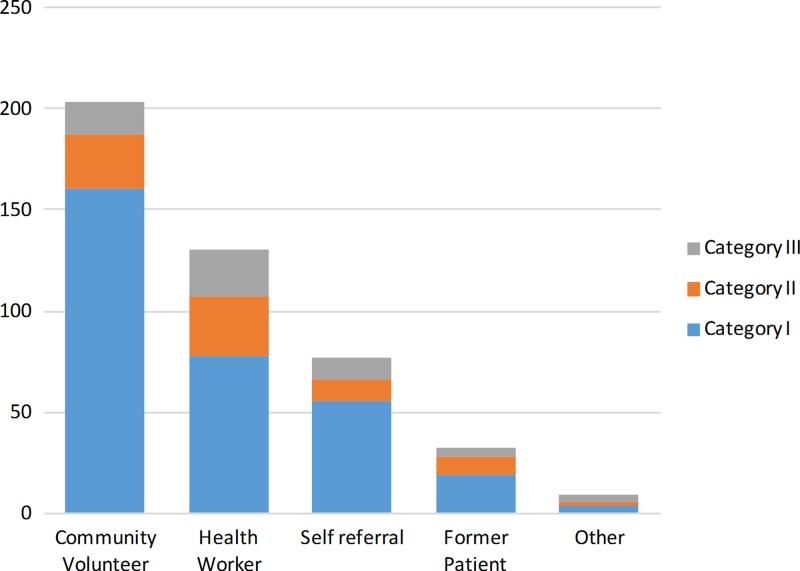

To measure the impact of the early detection activities at Agogo, we collected clinical data from patients seen at the Agogo BU Clinic between 2009 and 2013. We chose 2009 as the start, because by this year, PCR confirmation of cases had become standard practice. The total number of BU cases seen for the period was 451; 53% of cases were female, and 58% of cases were younger than 16 years. The categories of lesions by source of referral are shown in Figure 1. In total, 70% of patients presented with a category I lesion, 17% of patients presented with a category II lesion, and 13% of patients presented with a category III lesion. Forty percent of patients presented with nodules. CBSVs were the single most important source of cases for the clinic over the past 5 years, with 45% of cases being referred by them. Other referrals came from health workers or former patients, or they were self-referrals.

Figure 1.

Category of lesions by source of referral (Agogo Buruli Ulcer Clinic 2009–2013).

CBSVs reported more cases in the early stages of the disease than any other group; 79% of cases referred by CBSVs were category I lesions compared with 60% of cases referred by health workers (P < 0.001 by χ2), 72% of cases that were self-referrals (not significant by χ2), and 59% of cases referred by former patients (P = 0.013 by χ2). Another indicator of early detection is the percentage of patients who present in the earliest—nodular—stage; 49% of cases referred by CBSVs were nodules versus 38% of cases referred by health workers (P = 0.047 by χ2), 33% of cases that were self-referrals (P = 0.014 by χ2), and 41% of cases referred by former patients (not significant by χ2).

Of 451 cases reported, 375 (83%) cases were confirmed by PCR. As an indication for the quality of the referrals by CBSVs, the rate of cases that were confirmed by PCR did not differ between CBSVs and health workers (86% versus 83%; not significant by χ2).

Originally, care for BU was largely hospital-based, with an average duration of hospitalization of more than 100 days.13 However, the advent of successful antibiotic treatment together with early detection have the potential to shift the focus to community-based care. Although a high standard of clinical care is still necessary for more advanced cases, we believe that national and local programs should now focus on public health aspects of BU control—health education and early detection.

The CBSVs program at Agogo is a relatively simple and inexpensive program that uses lay community members who receive basic training and are provided with modest logistic support. As our findings show, this program is the largest source of BU cases referred to the clinic, with a good quality of referrals and more patients in the early stages of the disease than any other referral source. Early detection can drastically reduce the need for surgery and advanced wound care. This, in turn, can pave the way for decentralized care in the affected communities, reducing the impact on the healthcare system and the loss of schooling and productivity associated with prolonged hospitalization.

A key element of the program is the financial incentive scheme, which motivates the CBSVs to invest time in their task. Based on the number of cases reported in this paper, the cost of implementing this incentive scheme was less than US$400 per year. The incentive is only given for PCR-confirmed cases. This ensures that the clinic is not flooded with dubious referrals simply to obtain an incentive, and it motivates the CBSVs to develop good diagnostic skills.

Certainly, there will be circumstances where the structure of the Agogo BU program might be less appropriate. For instance, in situations where cases are scattered across the country, distances are extremely large, or cases only present in small numbers, an extensive system of village volunteers liaising with local health posts might not be cost-effective, but our experience can be adapted to the local situation. In endemic areas, a strong focus on early detection involving CBSVs coupled with standardized but decentralized treatment will likely minimize the need for long hospitalization and surgery and prevent disability.

Footnotes

Authors' addresses: Kabiru Mohammed Abass, Justice Abotsi, Samuel Osei Mireku, and William N. Thompson, Buruli Ulcer Clinic, Agogo Presbyterian Hospital, Agogo, Ghana, E-mails: abas@agogopresbyhospital.org, info@agogopresbyhospital.org, inf@agogopresbyhospital.org, and wnat111@yahoo.com. Tjip S. van der Werf, Ymkje Stienstra, and Sandor-Adrian Klis, Department of Internal Medicine–Infectious Diseases, University of Groningen, University Medical Center, Groningen, The Netherlands, E-mails: t.s.van.der.werf@umcg.nl, y.stienstra@umcg.nl, and s.klis@umcg.nl. Richard O. Phillips and Fred S. Sarfo, Internal Medicine, Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital, Kumasi, Ghana, and School of Medicine, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana, E-mails: rodamephillips@gmail.com and stephensarfo78@gmail.com. Kingsley Asiedu, Neglected Tropical Diseases, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, E-mail: asieduk@who.int.

References

- 1.Portaels F, Silva MT, Meyers WM. Buruli ulcer. Clin Dermatol. 2009;27:291–305. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2008.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mulder AA, Boerma RP, Barogui Y, Zinsou C, Johnson RC, Gbovi J, van der Werf TS, Stienstra Y. Healthcare seeking behaviour for Buruli ulcer in Benin: a model to capture therapy choice of patients and healthy community members. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008;102:912–920. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stienstra Y, van der Graaf WT, Asamoa K, van der Werf TS. Beliefs and attitudes toward Buruli ulcer in Ghana. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002;67:207–213. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2002.67.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nienhuis WA, Stienstra Y, Thompson WA, Awuah PC, Abass KM, Tuah W, Awua-Boateng NY, Ampadu EO, Siegmund V, Schouten JP, Adjei O, Bretzel G, van der Werf TS. Antimicrobial treatment for early, limited Mycobacterium ulcerans infection: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;375:664–672. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61962-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barogui Y, Johnson RC, van der Werf TS, Sopoh G, Dossou A, Dijkstra PU, Stienstra Y. Functional limitations after surgical or antibiotic treatment for Buruli ulcer in Benin. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;81:82–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stienstra Y, van Roest MH, van Wezel MJ, Wiersma IC, Hospers IC, Dijkstra PU, Johnson RC, Ampadu EO, Gbovi J, Zinsou C, Etuaful S, Klutse EY, van der Graaf WT, van der Werf TS. Factors associated with functional limitations and subsequent employment or schooling in Buruli ulcer patients. Trop Med Int Health. 2005;10:1251–1257. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization . WHO Fact Sheet on Buruli Ulcer, 2012. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saka B, Landoh DE, Kobara B, Djadou KE, Yaya I, Yekple KB, Piten E, Balaka A, Akakpo S, Kombate K, Mouhari-Toure A, Kanassoua K, Pitche P. Profile of Buruli ulcer treated at the national reference centre of Togo: a study of 119 cases. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 2013;106:32–36. doi: 10.1007/s13149-012-0241-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chauty A, Ardant MF, Adeye A, Euverte H, Guedenon A, Johnson C, Aubry J, Nuermberger E, Grosset J. Promising clinical efficacy of streptomycin-rifampin combination for treatment of Buruli ulcer (Mycobacterium ulcerans disease) Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:4029–4035. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00175-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ackumey MM, Kwakye-Maclean C, Ampadu EO, de Savigny D, Weiss MG. Health services for Buruli ulcer control: lessons from a field study in Ghana. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5:e1187. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vouking MZ, Takougang I, Mbam LM, Mbuagbaw L, Tadenfok CN, Tamo CV. The contribution of community health workers to the control of Buruli ulcer in the Ngoantet area, Cameroon. Pan Afr Med J. 2013;16:63. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2013.16.63.1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vouking MZ, Tamo VC, Mbuagbaw L. The impact of community health workers (CHWs) on Buruli ulcer in Sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Pan Afr Med J. 2013;15:19. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2013.15.19.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Asiedu K, Etuaful S. Socioeconomic implications of Buruli ulcer in Ghana: a three-year review. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;59:1015–1022. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.59.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]