Abstract

Objective

Electrocorticography (ECoG) electrodes implanted on the surface of the brain have recently emerged as a potential signal platform for brain-computer interface (BCI) systems. While clinical ECoG electrodes are currently implanted beneath the dura, epidural electrodes could reduce the invasiveness and the potential impact of a surgical site infection. Subdural electrodes, on the other hand, while slightly more invasive, may have better signals for BCI application. Because of this balance between risk and benefit between the two electrode positions, the effect of the dura on signal quality must be determined in order to define the optimal implementation for an ECoG BCI system.

Approach

This study utilized simultaneously acquired baseline recordings from epidural and subdural ECoG electrodes while patients rested. Both macro-scale (2 mm diameter electrodes with 1 cm inter-electrode distance, 1 patient) and micro-scale (75 μm diameter electrodes with 1 mm inter-electrode distance, 4 patients) ECoG electrodes were tested. Signal characteristics were evaluated to determine differences in the spectral amplitude and noise floor. Furthermore, the experimental results were compared to theoretical effects produced by placing epidural and subdural ECoG contacts of different sizes within a finite element model.

Main Results

The analysis demonstrated that for micro-scale electrodes, subdural contacts have significantly higher spectral amplitudes and reach the noise floor at a higher frequency than epidural contacts. For macro-scale electrodes, while there are statistical differences, these differences are small in amplitude and likely do not represent differences relevant to the ability of the signals to be used in a BCI system.

Conclusions

Our findings demonstrate an important trade-off that should be considered in developing a chronic BCI system. While implanting electrodes under the dura is more invasive, it is associated with increased signal quality when recording from micro-scale electrodes with very small sizes and spacing. If recording from larger electrodes, such as traditionally used clinically, the signal quality of epidural recordings is similar to that of subdural recordings.

Keywords: Electrocorticography, ECoG, Brain Computer Interface, BCI, Neuroprosthetics, Dura, Subdural, Epidural

1. Introduction

In recent years, electrocorticography (ECoG) recordings, made from either epidural or subdural electrode contacts on the surface of the cortex, have emerged both as an important means to study human cortical electrophysiology (Fried, Ojemann et al. 1981; Allison, McCarthy et al. 1994; Crone, Miglioretti et al. 1998; Crone, Miglioretti et al. 1998; Jerbi, Ossandon et al. 2009; Miller, Zanos et al. 2009; Gaona, Sharma et al. 2011), as well as a signal platform for brain-computer interface (BCI) experiments when implanted beneath the dura acutely in humans (Leuthardt, Schalk et al. 2004; Leuthardt, Miller et al. 2006; Wilson, Felton et al. 2006; Felton, Wilson et al. 2007; Schalk, Miller et al. 2008; Schalk and Leuthardt 2011) and epidurally for chronic experiments in non-human primates (Rouse, Stanslaski et al. 2011; Rouse, Williams et al. 2013) due to its balance of invasiveness and signal quality. The initial work investigating the use of ECoG for BCI systems in humans was done using patients temporarily implanted with subdural ECoG grids as part of the clinical treatment for intractable epilepsy. These clinical electrode arrays typically have a diameter of a few millimeters and an inter-electrode spacing on the order of 1 cm (Engel 1996). Recent work has also investigated the use of subdural micro-ECoG arrays with smaller electrode sizes (on the order of hundreds of microns or smaller) and denser spacing in human patients (Leuthardt, Freudenberg et al. 2009; Wang, Degenhart et al. 2009; Kellis, Miller et al. 2010). The increased spatial resolution and smaller size of micro-ECoG arrays are an important technical step towards developing a chronic BCI system for clinical use. An important factor to consider in the development of micro-ECoG arrays is the impact of the human dura mater on the electrophysiological signals. While an epidural electrode array may reduce the risks of infection due to isolating the implant from the intracranial space as well as removing the increased risk for infection caused by a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak (Tenney, Vlahov et al. 1985; Mollman and Haines 1986; Korinek 1997), it is important to understand the trade-off in decreasing signal quality that would be experienced by moving the electrode arrays from a subdural to an epidural implantation.

There have been a number of previous studies based upon animal models that have evaluated the effect of the dura mater on ECoG signals. Perhaps the first measure of the signal quality of epidural ECoG is the usefulness in controlling a BCI system. To this end, studies in non-human primates have shown that epidural ECoG can be used for online control (Rouse and Moran 2009; Rouse, Stanslaski et al. 2011; Rouse, Williams et al. 2013) and that similar degrees of BCI performance are achieved using both local field potentials and epidural field potentials (Flint, Lindberg et al. 2012). Similarly, in offline analysis, epidural signals were used to effectively decode forelimb movements in rats (Slutzky, Jordan et al. 2011). Furthermore, macro-scale epidural ECoG signals have been used off-line to decode continuous three-dimensional hand trajectories in non-human primates over the course of several months (Shimoda, Nagasaka et al. 2012). Additionally, the optimal spacing of subdural and epidural electrode arrays was similar when comparing electrophysiologic recordings made utilizing ECoG arrays with 125 μm electrode contacts in rats with a finite element model of the rat brain (Slutzky, Jordan et al. 2010). While these studies indicate that epidural recordings may be similar to subdural recordings with regards to BCI applications in non-human models, there is a limited ability to generalize these studies to humans because of the different physiologic characteristics of the cortex and dura mater between humans and non-human animals (Shoshani, Kupsky et al. 2006; Treuting, Dintzis et al. 2012).

To date, there are a limited number of studies that have sought to characterize the effect of the dura on electrophysiologic recordings in humans (Slutzky, Jordan et al. 2010; Torres Valderrama, Oostenveld et al. 2010). Based on the rat model described above, a finite element model of human cortex was constructed and the authors concluded that the optimal electrode spacing was similar between epidural and subdural recordings (Slutzky, Jordan et al. 2010). There were, however, no electrophysiological recordings in humans to confirm this, and the analysis examined only the spacing of electrodes and not the effect of the dura on the amplitude of ECoG signals (Slutzky, Jordan et al. 2010). In another study, epidural BCI performance was simulated by acquiring epidural and subdural signals intraoperatively, and then applying a transfer function to BCI control derived from subsequent subdural signals acquired extraoperatively (Torres Valderrama, Oostenveld et al. 2010). Here again, the authors concluded that the dura had little effect. While the study found that the transformed signals would still allow for adequate BCI performance, the study is limited for several reasons. First, the intraoperative condition in which the transfer function of the dura was evaluated is different from the alert brain state during BCI control. In particular, the consistent decreases in gamma band power caused by anesthesia (Breshears, Roland et al. 2010) means that while the transfer function may be accurate for low frequency rhythms, it may not extrapolate to the higher frequency gamma band. It is this high gamma range in particular, that is often used for ECoG BCI control (Rickert, Oliveira et al. 2005; Heldman, Wang et al. 2006; Leuthardt, Schalk et al. 2009; Schalk and Leuthardt 2011). Second, the study only evaluated the effects of the dura on clinical electrode arrays, which are much larger and more spatially diffuse than the arrays that would likely be used for a chronically implanted BCI system. The different signal characteristics of micro-scale arrays, due to both sampling a smaller area of cortex and recording from electrodes with higher electrical impedances should be considered in evaluating the effects of the dura on ECoG signals.

To address the question of how the dura affects electrophysiologic recordings in humans, this study investigated the effects of the human dura on ECoG signals from humans during awake, resting periods at both the macro- and micro-scale. We use both simultaneous electrophysiological recordings of macro- and micro-scale ECoG arrays as well as a finite element model of human cortex. The results of both techniques show that while there is little difference in macro-scale ECoG signals from above or below the dura, that micro-scale ECoG signals have very different amplitudes, spectral resolution, and spatial resolution.

2. Methods

2.1 Micro-ECoG experiments

2.1.1 Patients

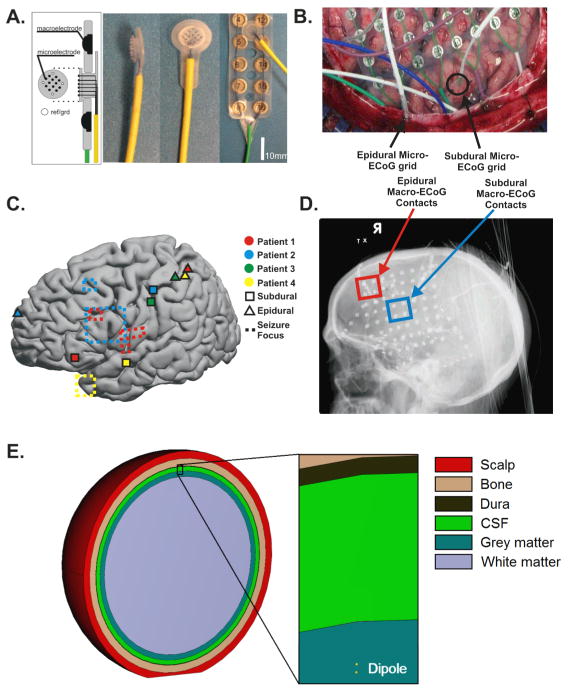

The patients that participated in this study underwent temporary placement of intracranial electrode grids to identify epileptic seizure foci. Four patients provided informed consent for the placement of two micro-electrode arrays for research purposes (Figure 1A). In each subject, one micro-electrode array was placed beneath the dura, in between or peripheral to the macro-scale contacts of a clinical ECoG grid. A second micro-electrode array was slid below the skull superficial to the dura outside of the boundary of the craniotomy (Figure 1B). Electrode arrays were localized using radiographs and the “get location on cortex” technique (Figure 1C and 1D) (Miller, Makeig et al. 2007). Additionally, all micro-ECoG grid locations were compared to the cortical areas identified by the epileptologists as seizure foci or propagation regions to confirm that they did not overlap. All patients provided informed consent for the study, which were reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of Washington University School of Medicine.

Fig. 1. Electrophysiologic and finite element modeling methods.

A. A novel microelectrode with 70 μm electrode diameter and 1 mm inter-electrode spacing was implanted both epidurally and subdurally in 4 patients. The grids contained 12 cortically facing channels and 4 impedance-matched, skull-facing contacts to choose from for a ground and a reference contact. B. Subdural microgrids were implanted either in between or to the outside of clinical ECoG contacts. Epidural microgrids were slid between the dura and skull beyond the boundaries of the craniotomy. C. Locations of subdural and epidural microgrids across patients and cortical areas identified as epileptic foci or propagation regions. The seizure focus of Patient 3 is not visible as it was located sub-temporally. D. In an additional patient, due to an adherent dura during the implant surgery, a corner of the clinical ECoG grid was superior to the dura, allowing for comparison of epidural and subdural macro-ECoG signals in identical geometric configurations, allowing for comparison of the effect of the dura across electrode geometry. E. A schematic shows the geometric organization of the FE model. The model consisted of spherical subdomains with a radially oriented dipole placed within the gray matter layer. Electrodes of various diameters were simulated on the superior surface of the dura (epidural) or on the surface of the gray matter (subdural).

2.1.2 Electrocorticography Specifications

A special research micro-electrode array was designed and utilized (PMT Corporation, Chanhassen, MN). Each electrode array consisted of 16 platinum iridium micro-wires with a diameter of 75 μm and an interelectrode spacing of 1 mm. Figure 1A shows a schematic of the array and photographs of the micro-electrode array alone and placed relative to a standard clinical electrode array. Of the 16 contacts on the research micro-array, 12 micro-wire contacts were cortically facing and the 4 contacts at the corners of the array (spaced 3 mm apart) were skull-facing. The skull-facing contacts were designed so that two of the 4 non-cortical, impedance-matched contacts with good quality signals could be used as ground and reference contacts for the recordings. Additionally, shielded cables were used to connect the micro-ECoG arrays to the amplifiers in order to increase the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR).

2.1.3 Electrocorticography Recordings and Preprocessing

Electrocorticography signals were acquired using biosignal amplifiers manufactured by g.tec (Graz, Austria). The combination of two out of the four upward facing contacts producing the cleanest signals was selected for use as ground and reference channels. Signals were sampled with 24-bit resolution with an internal sampling rate of 38.4 kHz and an internal 5 kHz antialiasing filter. Data were recorded with a sampling rate of 2.4 kHz. No additional filters were used.

The BCI2000 software package was utilized to record ECoG signals while patients were resting (Schalk, McFarland et al. 2004). During the recordings, patients were positioned in their hospital bed in the semi-recumbent position. Patients were instructed to rest quietly and to remain as still as possible for the duration of the recordings. In patients 2, 3, and 4, the epidural and subdural contacts were recorded simultaneously for a period of 5–10 consecutive minutes. In the final patient, patient 1, the subdural and epidural contacts were recorded for distinct epochs of approximately 5 minutes each within a total time window of approximately 25 minutes.

After initial data collection, a number of steps were taken to preprocess the data. First, the data were high pass filtered at 0.5 Hz. Next, the data was notch filtered to remove all 60 Hz harmonics below the Nyquist frequency from the data. The signals were then manually inspected to determine noisy channels which were then removed from further analysis. All remaining channels were then averaged and regressed from the signal by calculating a regression coefficient of the common average to each channel and removing the weighted common average signal from each channel. Finally, the data was manually inspected to determine time intervals in which artifacts were present and the remaining time periods were segmented into 10 second windows with 5 second overlaps between windows for use in the analyses described below. Figure 2 (upper plots) shows an exemplar 10 second time window from the subdural and epidural micro-ECoG grids from a single patient.

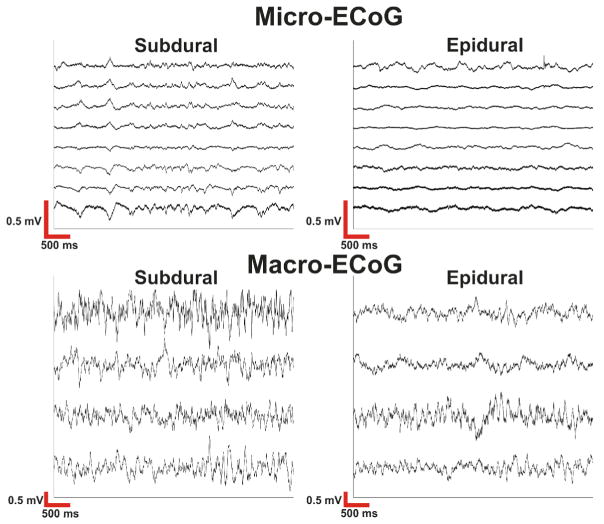

Fig. 2. Raw electrocorticography signals.

Within micro-ECoG recordings the signals were fairly correlated across channels and there was a large difference in amplitude between subdural and epidural signals. Macro-ECoG signals demonstrate smaller amplitude differences between subdural and epidural contacts. Macro-ECoG signals are also less correlated and have higher signal amplitudes than micro-ECoG signals.

2.1.4 Power Spectral Density Analysis

An initial analysis was performed to examine the characteristics of the power spectrum in epidural and subdural recordings. The power spectral density [P(f,c,w) where f is the frequency bin, c is the channel, and w is the temporal window] was calculated as the square of the fast Fourier transform of each channel for each 10 second time window with a frequency resolution of 1 Hz. The power spectral densities for both epidural and subdural contacts were then converted to normalized spectra, PN, by dividing the spectra by the 99th percentile of power from any epidural or subdural contact (P99) from the respective patient, as described in Equation 1. This allowed the power spectra (in decibels) of both epidural and subdural recordings to be compared on the same scale.

| (1) |

As ECoG power spectra are not normally distributed, they were normalized with a log transform. The log-transformed normalized spectra were concatenated across channels and time windows. Prior to comparing the epidural and subdural contacts, the normality of the distributions of log-transformed amplitudes at each frequency band was verified through visual inspection of a subset of frequencies and by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Finally, the average log-transformed power spectra across time windows and channels of the epidural and subdural recordings were compared through an independent samples t-test. Multiple comparison correction was performed using the Benjamini-Hochberg-Yekutieli method of False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction (Benjamini and Hochberg 1995; Benjamini and Yekutieli 2001) to correct for the number of frequency bands compared while accounting for the correlated nature of the test statistics.

2.1.5 Calculation of Noise Floor

In addition to comparing the normalized amplitudes of epidural and subdural recordings, it was hypothesized that a more meaningful measure of signal quality would be the spectral noise floor of recordings. Spectral analyses of ECoG recordings are characterized by a 1/f decrease in amplitude at frequencies below the noise floor and a flat power spectrum at frequencies above the noise floor (Miller, Sorensen et al. 2009). To examine the noise floor in epidural and subdural recordings the noise floor of each micro-ECoG grid was estimated using the power spectrum from each channel and temporal window between 550 Hz and 597 Hz. This frequency band was chosen as it was the highest frequency band located below the Nyquist frequency and between any 60 Hz harmonics. Next, the average log-transformed power spectra from the epidural and subdural recordings were compared to their respective noise floors using an independent samples t-test. Multiple comparison correction was performed using the Benjamini-Hochberg-Yekutieli method of False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction (Benjamini and Hochberg 1995; Benjamini and Yekutieli 2001).

2.2 Macro-ECoG Experiment

As a secondary analysis to evaluate the effect of the dura on human clinical macro-ECoG electrodes, we identified a single patient who performed BCI experiments described previously (Leuthardt, Miller et al. 2006). During the implantation surgery, the dura was found to be adherent to the brain, therefore a corner of the clinical ECoG grid was superior to the dura while the remainder of the grid was inferior to the dura, allowing for evaluation of the effects of the human dura on macro-ECoG signals with an exposed electrode diameter of 2 mm and an interelectrode distance of 1 cm (Ad-Tech Corporation, Racine, WI) (Figure 1D). Signals were recorded with Synamps2 amplifiers (Neuroscan, El Paso, TX). Signals were bandpass filtered (0.1–220 Hz) and digitized at 1000 Hz. As in the micro-ECoG experiments described above, recordings were made while the patients rested quietly in their hospital bed in a semi-recumbent position. As 4 electrodes at the corner of the grid were located superior to the dura, 4 subdural electrodes in the same geometric configuration confirmed to be subdural and not located on the border of the cut dura were used for comparison. The preprocessing for the macro-ECoG signals was the same as for the micro-ECoG signals with the common average calculated from the entire ECoG array of 64 channels. Power spectral densities were calculated for the macro-ECoG contacts using the methods from the micro-ECoG experiments described above. As this recording was made with a bandpass filter (0.1–220 Hz), it was not possible to isolate the system noise floor from the hardware filters in order to determine the frequency at which the signals reached the system noise floor. While these recordings were from a single patient and made with a different recording system, they provided the unique opportunity to evaluate macro-ECoG signals from above and below the dura in awake humans and to compare the effect of the dura on ECoG recordings at different spatial scales from the micro-ECoG recordings described above and with existing literature examining of the effect of the dura on clinical ECoG recordings in an intraoperative setting (Torres Valderrama, Oostenveld et al. 2010).

2.3 Modeling

A finite element (FE) model of the human head was created using Comsol Multiphysics (V.3.4, Comsol, Stockholm, Sweden). The model consisted of spherical subdomains representing white matter, gray matter, CSF, dura mater, scalp and skin. The thickness and conductivity of each subdomain were assigned based on previously reported values and are summarized in Table 1. Cortical source regions were modeled as radially oriented dipoles consisting of pairs of idealized current sources. A schematic of the geometric organization of the FE model is shown in Figure 1E. The FE model was used to solve the potential distribution at the cortical surface and the surface of the dura for dipoles placed at different depths. This information was then used to calculate the potential generated at a point electrode from unitary current sources located at different radial displacements. Dipoles placed at varying depths (0.3–1.5 mm, 0.2 mm increments) were evaluated. The FE model was solved at ~800,000 tetrahedra with a maximum element size of 400 μm in the volume closest to the dipole.

Table 1.

Thickness and conductivity values for each explicitly represented subdomain.

To evaluate the effect of different electrode diameters on recorded potentials, the potential-distance relationships generated using the methodology described above was curve fitted in Matlab (2011a) using high order sums of sine and Gaussian functions, producing a set of expressions that can be used to calculate the potential generated at any point by a dipole at an arbitrary radial displacement. The surface area of the electrodes with diameters ranging from 75 μm–10 mm was then discretized into ~800,000 points and a second set of potential-distance relationships were calculated by averaging the potentials generated across the surface area of the electrodes by dipoles at different radial displacements.

3. Results

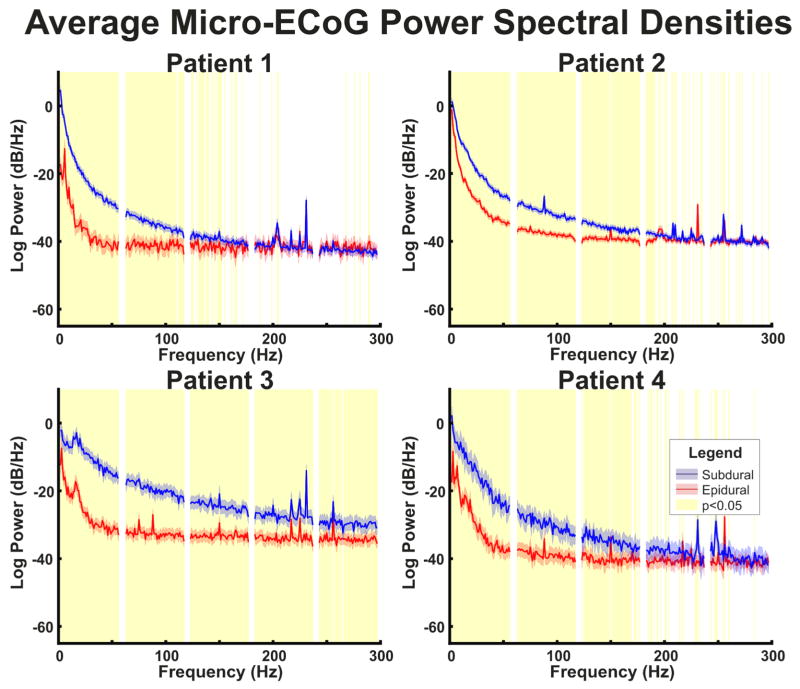

Recordings from each patient demonstrated significant effects of the dura on micro-ECoG recordings. Figure 2 (upper plots) demonstrates exemplar epidural and subdural micro-ECoG recordings. In particular, the micro-ECoG recordings have noticeably higher amplitudes in subdural signals as compared to epidural signals. The calculated averaged power spectral densities confirm the observed differences in amplitude between epidural and subdural micro-ECoG recordings. Each patient’s averaged power spectral densities for subdural and epidural micro-ECoG signals are shown in Figure 3. In particular, each of the 4 patients demonstrated spectral power in subdural recordings that was significantly higher (p<0.05) than in epidural recordings in a range up to at least 150 Hz.

Fig. 3. Micro-ECoG power spectral densities.

Patient-specific averaged power spectral densities for epidural and subdural micro-ECoG contacts. Averaged power spectra were calculated across time windows and electrode channels. Confidence intervals represent the 95% confidence interval of the power spectral density. Areas highlighted in yellow represent frequencies with a significant (p<0.05) difference between power in epidural and subdural recordings corrected for multiple comparisons with false discovery rate. Power is higher in subdural recordings than epidural recordings in frequencies below 150 Hz in all patients and the 1/f decrease in amplitude is less steep in subdural recordings than epidural recordings.

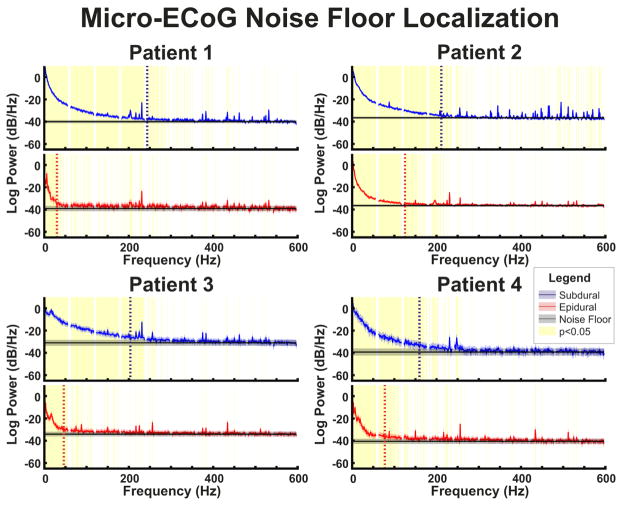

While the differences in spectral amplitudes are informative, it was also important to determine the spectral frequency at which the noise floor of the ECoG signals is reached. Figure 4 displays the power spectral densities of micro-ECoG recordings along with the noise floor estimated using the power spectra between 550–597 Hz for the subdural and epidural grids respectively. As can be seen in the power spectral density plots (Figure 3) as well as the comparison of the power spectral density with the noise floor (Figure 4), micro-ECoG recordings displayed a decrease in amplitude with increasing frequency consistent with a 1/f trend. Furthermore, after flattening out, the power spectrum is flat up to the upper bound of the analysis (597 Hz), confirming that there are no other hardware filters affecting the analysis. Importantly, in micro-ECoG recordings, the frequency where the recorded signal and the noise floor converge (i.e. the lowest frequency at which they are first not significantly differently) was at least 83 Hz lower for epidural signals than for subdural signals in all 4 patients. In particular, the epidural power spectrum was first not significantly different from the noise floor at between 30 Hz and 123 Hz and the subdural power spectrum was first not significantly different from the noise floor at between 160 Hz and 243 Hz.

Fig. 4. Micro-ECoG noise floor comparison.

Patient-specific power spectral densities averaged across channels and time windows are shown relative to the grid-specific noise floors. Noise floors were determined based upon the power between 550–597 Hz. In all patients power spectra are flat from the frequency at which the noise floor was reached through the end of the analysis range. Vertical lines indicate the lowest frequency at which the power spectrum was not significantly different from the noise floor. This location is reached at higher frequencies for subdural recordings than epidural recordings in each patient. Confidence intervals represent the 95% confidence interval of the power spectral density and noise floor. Areas highlighted in yellow represent frequencies with a significant (p<0.05) difference between power in epidural and subdural recordings and their respective noise floors, corrected for multiple comparisons with false discovery rate.

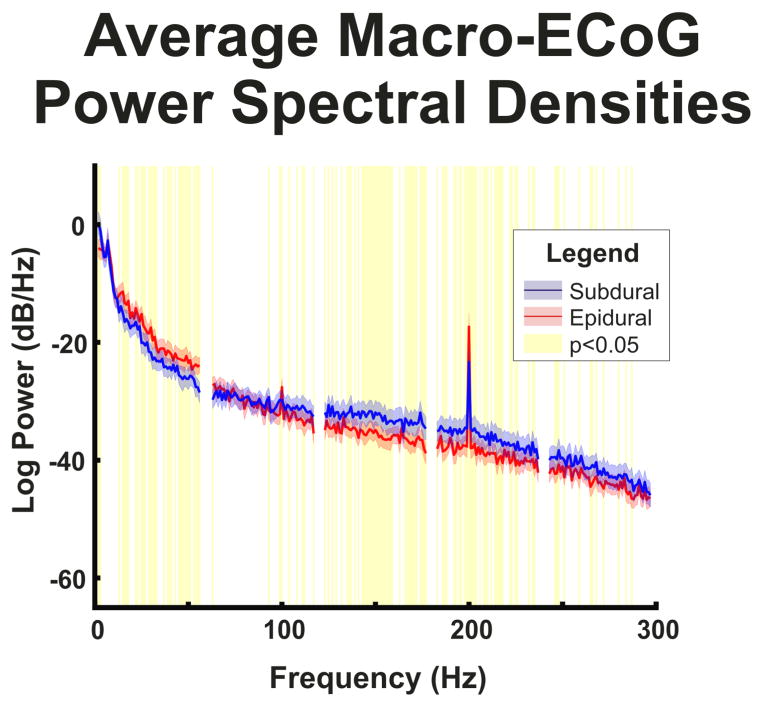

Additionally, the human dura was found to have a different effect on micro-ECoG signals when compared to macro-ECoG signals. In particular, the dura affects micro-ECoG signals much more than macro-ECoG signals. In comparing the exemplar macro- and micro-ECoG recordings (Figure 2), there is a large difference in amplitude between the macro- and micro-ECoG signals and the micro-ECoG traces appear more correlated to each other than the macro-ECoG traces. Both of these findings are expected due to the smaller electrode spacing and higher impedance of micro-scale electrodes. Furthermore, while less marked than the difference caused by electrode size, the macro-ECoG recordings appeared to have similar amplitudes for both subdural and epidural recordings, while there is a marked difference in amplitude between subdural and epidural micro-ECoG recordings. Additionally, the power spectra of the macro-ECoG recordings (Figure 5) show statistically significant differences in spectral amplitude between subdural and epidural contacts characterized by higher amplitudes in the epidural contacts in the 10–60 Hz range and higher amplitudes in the subdural contacts in the 90–240 Hz range.

Fig. 5. Macro-ECoG power spectral densities.

Power spectral densities for epidural and subdural macro-ECoG contacts averaged across channels and time windows. Confidence intervals represent the 95% confidence intervals of the power spectral density. Areas highlighted in yellow represent frequencies with a significant (p<0.05) difference between power in epidural and subdural recordings corrected for multiple comparisons with false discovery rate. Although power is higher in epidural recordings at low frequencies and higher in subdural recordings in high frequencies, the 1/f decrease in power is similar in subdural and epidural recordings.

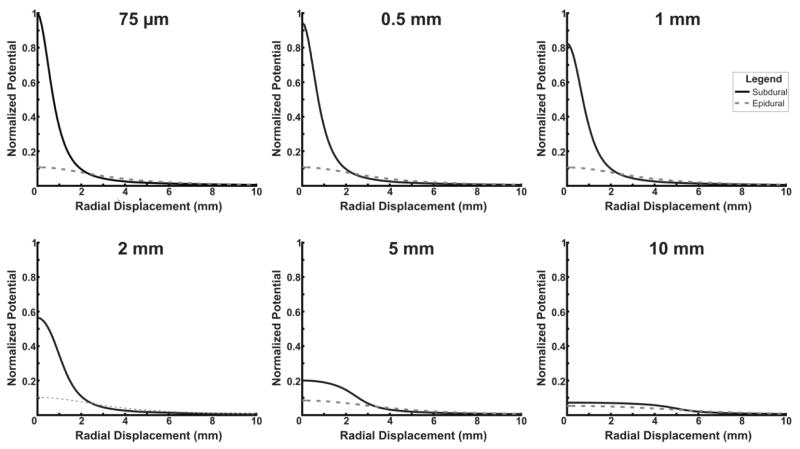

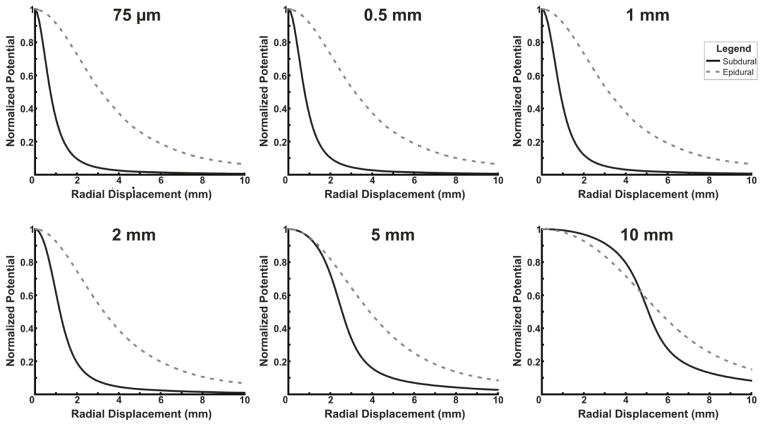

Finally, simulations from a finite element model of the human head confirm the empirical results. Figure 6 and 7 display the amplitudes for various electrode sizes placed subdurally or epidurally at various radial displacements from a dipole source with a depth of 0.9 mm. In Figure 6, signals are normalized to the maximum amplitude signal from any electrode size and location (a 75 μm subdural electrode placed directly over the source). In Figure 7, signals are normalized to the amplitude with no radial displacement. Overall, for small electrode sizes, there is a large difference in the raw amplitude between subdural and epidural contacts; for larger electrode sizes, the difference is much smaller (Figure 6). Furthermore, Figure 7 demonstrates that the differences between subdural and epidural electrodes in the decrease in signal amplitude with increasing radial displacement from the source is much greater for smaller electrode sizes than larger electrode sizes. Simulations were performed at multiple dipole depths in addition to the depth of 0.9 mm shown in Figures 6 and 7. At other depths, a similar effect was observed with the magnitude of the differences between epidural and subdural recordings inversely related to the depth of the dipole placement.

Fig. 6. Finite element model comparison of amplitude based on electrode size.

A finite element model was used to compare the amplitude produced by a dipole point source at electrodes with various diameters and varying radial displacements from the source. All traces are normalized to the maximum amplitude of the 75 μm subdural electrode. Small electrodes have large differences in amplitude between epidural and subdural electrodes, while at large diameters, electrodes have much smaller differences in amplitude between subdural and epidural electrodes.

Fig. 7. Finite element model comparison of spatial specificity based on electrode size.

A finite element model was used to compare the decrease in amplitude as radial displacement from a dipole point source increases in electrodes with various diameters. All traces are normalized to the amplitude at 0 mm radial displacement. Small electrodes have large differences in the changes in amplitude with radial displacement between epidural and subdural electrodes, while at large diameters, electrodes have much smaller differences between subdural and epidural electrodes.

4. Discussion

This paper provides a demonstration of the effect of the human dura mater on the signal characteristics of ECoG recordings at multiple scales utilizing both electrophysiological recordings and theoretical modeling. In particular, the signal amplitude of epidural micro-ECoG recordings is significantly smaller than that of subdural micro-ECoG recordings. Furthermore, the signal amplitude derived from epidural macro-ECoG, while statistically higher than subdural macro-ECoG in low frequencies (10–60 Hz) and lower than subdural macro-ECoG at high frequencies (90–240 Hz), given the small magnitude of these differences in macro-ECoG power spectra, these differences would probably not affect the ability for either subdural or epidural macro-ECoG electrodes to be used in a BCI system. Experimentally epidural micro-ECoG signals have lower spectral amplitudes than subdural micro-ECoG signals across all frequency bands below the noise floor (which is reached at a lower frequency than for subdural micro-ECoG signals). Additionally, theoretical modeling demonstrates reduced amplitude and spread of voltage potential recorded from epidural contacts when compared to subdural contacts for micro-ECoG electrodes. However, as electrode size approaches that of currently used clinical macro-ECoG electrodes (~2 mm diameters), computer simulations suggest very little difference in signal amplitudes between subdural and epidural recordings. These findings have important implications for the development of chronic, implantable ECoG electrodes.

This study is unique in the examination of the effect of the dura mater on ECoG recordings electrophysiologically both in that the study focuses on humans and on different scales of electrode size. While macro-scale ECoG electrodes (on the order of millimeters in diameter with an interelectrode distance on the order of 1 cm), placed below the dura, have been utilized clinically for many years (Penfield and Jasper 1954; Engel 1996), the advent of ECoG as a potential signal platform for BCI systems (Leuthardt, Schalk et al. 2004) introduced an important question as to the effect of the dura mater on ECoG signal quality. To be applied as a control signal for a chronically utilized BCI system, ECoG signals need to be chronically stable and must balance the desire for multiple independent degrees of freedom with the desire to minimize the invasiveness of the implant. Micro-scale ECoG recordings with smaller electrode size and spacing have demonstrated an improved spatial resolution and degree of behavioral information that can be decoded from ECoG signals (Leuthardt, Freudenberg et al. 2009; Wang, Degenhart et al. 2009; Kellis, Miller et al. 2010) and could reduce the invasiveness of a chronic BCI system. Furthermore, as the outside of the dura is part of the peripheral immune system, epidural ECoG has been proposed as a method to limit the invasiveness of chronic implants and reduce the chances of an infection within the central nervous system (Tenney, Vlahov et al. 1985; Mollman and Haines 1986; Korinek 1997; Moran 2010). While implanting ECoG arrays epidurally would reduce the invasiveness of a chronic BCI system, it is important to understand the trade-offs in terms of signal quality that would result from electrodes being further away from the brain, particularly for micro-scale electrode arrays. While a number of studies point to the ability to decode information from epidural contacts in animal models (Rouse and Moran 2009; Slutzky, Jordan et al. 2011; Flint, Lindberg et al. 2012; Shimoda, Nagasaka et al. 2012; Rouse, Williams et al. 2013), it is necessary to understand whether the different anatomy of the dura in humans would further impair epidural ECoG recordings (Shoshani, Kupsky et al. 2006; Treuting, Dintzis et al. 2012).

The results of the study clearly show that at the micro-scale, the dura has significant effects on signal amplitude. Previous ECoG BCI studies have demonstrated the importance of the high gamma band (70–105 Hz) for BCI applications (Leuthardt, Schalk et al. 2004; Leuthardt, Miller et al. 2006; Wilson, Felton et al. 2006; Felton, Wilson et al. 2007; Schalk, Miller et al. 2008; Rouse and Moran 2009; Schalk and Leuthardt 2011). While low frequency changes in power have also been shown to be important for BCI control (Leuthardt, Schalk et al. 2004), the high frequency power changes are more anatomically focal (Miller, Leuthardt et al. 2007), indicating that the high gamma band may allow for BCI systems with higher degrees of freedom. Importantly, the results demonstrate that the amplitude of subdural micro-ECoG signals is higher than the amplitude of epidural micro-ECoG signals at all frequencies below 150 Hz (Figure 3), indicating that subdural micro-ECoG signals will generally have a higher SNR. While there were also significant differences in spectral amplitude between epidural and subdural macro-ECoG signals, the magnitude of the differences are small and the theoretical modeling results demonstrate smaller effects of the dura on macro-ECoG signals than for micro-ECoG signals. While we cannot compare task-based activations between epidural and subdural micro-ECoG arrays due to their different cortical locations, it is reasonable to conclude that while it may be possible to record high-gamma band activity from epidural micro-ECoG electrodes, that the differences in spectral amplitude and noise floor locations between epidural and subdural micro-ECoG arrays would lead to higher SNR in subdural electrodes during performance of a task. For all of these reasons, it appears that while the effect of the dura on micro-ECoG signals is statistically significant and would likely lead to poorer BCI performance with epidural electrodes than with subdural electrodes, that given the small magnitude of the differences between subdural and epidural macro-ECoG signals, epidural macro-ECoG contacts would likely not lead to large changes BCI performance relative to subdural contacts.

It should also be noted that while there were several technical factors that optimized the quality of micro-ECoG recordings in this study, there are several future technical developments that could further improve the quality of the signals. The use of impedance matched, skull-facing ground and reference contacts as well as shielded connectors to connect the electrode arrays and amplifiers likely increased the SNR of the signals, allowing for recording of physiologic micro-ECoG signal. However, the high impedance of the electrode contacts due to their small size causes the amplitude of physiologic signals recorded to be low and therefore decreases the SNR. The development and use of coatings to increase the surface area of the electrode contacts would decrease the electrode impedance and increase the SNR (Venkatraman, Hendricks et al. 2011). Additionally, the development of FDA approved preamplifiers that could be located closer to the site of the electrode array could also increase the SNR of the signal. Although these developments would likely allow epidural micro-ECoG arrays to be better applied to BCI systems, they would also further improve the signal quality of subdural micro-ECoG arrays. Therefore while both epidural and subdural micro-ECoG signals could be further improved, the superiority of subdural micro-ECoG implants to epidural micro-ECoG implants would not change.

While this work represents an important evaluation of the effect of the human dura on ECoG signal quality, there are several limitations and future considerations to note. Ultimately, the best measure of ECoG signal quality in relationship to BCI applications is the ability for behavioral intentions to be predicted from neural signals. Because of the differences in subject specific anatomy and the strength and characteristics of neural activity between patients, comparison of decoding from one or more cortical regions across patients would not be meaningful in examining the effects of the human dura on electrophysiologic recordings. Additionally, the differences in relationships between cortical activity and behavior across two different locations on cortex, even within a single functional (e.g. Brodmann’s) area, makes simultaneous comparison of signal quality from two grids within a single subject impossible. Because of this, we determined that the evaluation of signal characteristics during baseline activity from a single patient would provide the best possible method for evaluating the effect of the human dura on ECoG signals. There is also some concern that differences in cortical activity could affect the results, because the subdural and epidural recordings were made from different cortical areas. While it is impossible to entirely control a patient’s conscious thoughts, patient behavior was visually screened to ensure that subjects were truly resting and that periods of movement were removed from the recordings. Furthermore, the results were consistent across all 4 patients with subdural and epidural micro-ECoG grid locations that were widely distributed across the brain (Figure 1C). Therefore, it seems reasonable to assume that the differences in signal quality were not caused by behavior but by the placement of the electrodes relative to the dura. Since the patients utilized were chronic epilepsy patients, an additional concern is that signals measured may have been affected by epileptic activity. All of the patients had focal epilepsy and care was taken to avoid areas near the epileptic foci during implantation, which was confirmed by subsequent comparison with the clinically determined epileptic foci (Figure 1C). All recordings were also made with a buffer period of at least one hour before or after any generalized seizure activity. Therefore, it can be reasonably assumed that the results represent normal physiologic and not epileptic activity. Additionally, while care was taken to visually verify that subdural micro-ECoG grids were not placed on blood vessels, as the epidural micro-ECoG grids were placed beyond the boundaries of the craniotomy, it was not possible to do this with the epidural arrays. While the effect of blood vessels on ECoG signals has been demonstrated previously (Bleichner, Vansteensel et al. 2011), the consistency of the spectral differences between epidural and subdural micro-ECoG arrays across all 4 patients indicates that the results were not spuriously caused by the placement of electrodes on blood vessels. It should be noted that the macro-ECoG recordings were made from a single patient and utilized a different recording system. Additionally, there were adhesions between the cortex and the dura and a cut in the dura in the area of the recordings. While it is possible that this may account for some of the differences observed between macro- and micro-ECoG recordings, it is likely that any effect of the adhesions would be to thicken the dura and increase the effect of the dura on the ECoG signals. Furthermore, while the macro-ECoG results presented here were only derived from a single patient, they are in line with experiments demonstrating little effect of the dura on BCI performance when the gain of the dura was estimated under anesthesia intraoperatively (Torres Valderrama, Oostenveld et al. 2010). Finally, while the computational modeling results indicate a significant effect of the dura on micro-ECoG recordings with little effect on macro-ECoG recordings, it is difficult to quantitatively determine the ideal electrode size computationally. As the signal profiles are sensitive to changes in geometries, particularly the width of the CSF layer (Slutzky, Jordan et al. 2010) and dipole depth, it is difficult to predict the optimal electrode size and spacing computationally.

In summary, these experimental and computational modeling results clearly demonstrate that for micro-ECoG arrays, subdural recordings have statistically significant differences from epidural recordings with magnitudes suggesting that the performance of BCI applications would suffer if epidural micro-ECoG electrodes were used, while for macro-ECoG arrays, subdural and epidural signals are similar. In particular, subdural micro-ECoG signals demonstrate increased signal amplitude, SNR, and spatial resolution. While implanting ECoG grids subdurally for chronic BCI applications is more invasive, the advantage is that smaller, micro-scale electrodes can be used. When implanting less invasive epidural ECoG electrodes, larger scale electrodes should be used. It is a tradeoff that must be optimized to the goals of the treatment.

Acknowledgments

This publication was supported by the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences grant UL1 TR000448, sub-award TL1 TR000449, from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. This work was also supported by the James S. McDonnell Foundation, the Doris Duke Foundation, National Institute of Health grant NIBIB 1R0100085606, and the National Science Foundation NSF EFRI-1137211. We would like to thank Jeff Ojemann for kindly contributing the macro-scale ECoG data. We would also like to thank the patients who participated in this study. Without their interest and effort this research would not be possible.

Footnotes

Disclosures: ECL and DWM have stock ownership in the company Neurolutions

References

- Allison T, McCarthy G, Nobre A, Puce A, Belger A. Human extrastriate visual cortex and the perception of faces, words, numbers, and colors. Cereb Cortex. 1994;4(5):544–554. doi: 10.1093/cercor/4.5.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate - a Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B-Methodological. 1995;57(1):289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Yekutieli D. The control of the false discovery rate in multiple testing under dependency. Annals of Statistics. 2001;29(4):1165–1188. [Google Scholar]

- Bleichner MG, Vansteensel MJ, Huiskamp GM, Hermes D, Aarnoutse EJ, Ferrier CH, Ramsey NF. The effects of blood vessels on electrocorticography. J Neural Eng. 2011;8(4):044002. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/8/4/044002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breshears JD, Roland JL, Sharma M, Gaona CM, Freudenburg ZV, Tempelhoff R, Avidan MS, Leuthardt EC. Stable and dynamic cortical electrophysiology of induction and emergence with propofol anesthesia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(49):21170–21175. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011949107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crone NE, Miglioretti DL, Gordon B, Lesser RP. Functional mapping of human sensorimotor cortex with electrocorticographic spectral analysis. II. Event-related synchronization in the gamma band. Brain. 1998;121(Pt 12):2301–2315. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.12.2301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crone NE, Miglioretti DL, Gordon B, Sieracki JM, Wilson MT, Uematsu S, Lesser RP. Functional mapping of human sensorimotor cortex with electrocorticographic spectral analysis. I. Alpha and beta event-related desynchronization. Brain. 1998;121(Pt 12):2271–2299. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.12.2271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel J., Jr Surgery for seizures. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(10):647–652. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603073341008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felton EA, Wilson JA, Williams JC, Garell PC. Electrocorticographically controlled brain-computer interfaces using motor and sensory imagery in patients with temporary subdural electrode implants. Report of four cases. J Neurosurg. 2007;106(3):495–500. doi: 10.3171/jns.2007.106.3.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flint RD, Lindberg EW, Jordan LR, Miller LE, Slutzky MW. Accurate decoding of reaching movements from field potentials in the absence of spikes. J Neural Eng. 2012;9(4):046006. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/9/4/046006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried I, Ojemann GA, Fetz EE. Language-related potentials specific to human language cortex. Science. 1981;212(4492):353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.7209537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaona CM, Sharma M, Freudenburg ZV, Breshears JD, Bundy DT, Roland J, Barbour DL, Schalk G, Leuthardt EC. Nonuniform high-gamma (60–500 Hz) power changes dissociate cognitive task and anatomy in human cortex. J Neurosci. 2011;31(6):2091–2100. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4722-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heldman DA, Wang W, Chan SS, Moran DW. Local field potential spectral tuning in motor cortex during reaching. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2006;14(2):180–183. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2006.875549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerbi K, Ossandon T, Hamame CM, Senova S, Dalal SS, Jung J, Minotti L, Bertrand O, Berthoz A, Kahane P, Lachaux JP. Task-related gamma-band dynamics from an intracerebral perspective: review and implications for surface EEG and MEG. Hum Brain Mapp. 2009;30(6):1758–1771. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellis S, Miller K, Thomson K, Brown R, House P, Greger B. Decoding spoken words using local field potentials recorded from the cortical surface. J Neural Eng. 2010;7(5):056007. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/7/5/056007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korinek AM. Risk factors for neurosurgical site infections after craniotomy: a prospective multicenter study of 2944 patients. The French Study Group of Neurosurgical Infections, the SEHP, and the C-CLIN Paris-Nord. Service Epidemiologie Hygiene et Prevention. Neurosurgery. 1997;41(5):1073–1079. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199711000-00010. discussion 1079–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leuthardt EC, Freudenberg Z, Bundy D, Roland J. Microscale recording from human motor cortex: implications for minimally invasive electrocorticographic brain-computer interfaces. Neurosurg Focus. 2009;27(1):E10. doi: 10.3171/2009.4.FOCUS0980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leuthardt EC, Miller KJ, Schalk G, Rao RP, Ojemann JG. Electrocorticography-based brain computer interface--the Seattle experience. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2006;14(2):194–198. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2006.875536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leuthardt EC, Schalk G, Roland J, Rouse A, Moran DW. Evolution of brain-computer interfaces: going beyond classic motor physiology. Neurosurg Focus. 2009;27(1):E4. doi: 10.3171/2009.4.FOCUS0979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leuthardt EC, Schalk G, Wolpaw JR, Ojemann JG, Moran DW. A brain-computer interface using electrocorticographic signals in humans. J Neural Eng. 2004;1(2):63–71. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/1/2/001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manola L, Roelofsen BH, Holsheimer J, Marani E, Geelen J. Modelling motor cortex stimulation for chronic pain control: electrical potential field, activating functions and responses of simple nerve fibre models. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2005;43(3):335–343. doi: 10.1007/BF02345810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KJ, Leuthardt EC, Schalk G, Rao RP, Anderson NR, Moran DW, Miller JW, Ojemann JG. Spectral changes in cortical surface potentials during motor movement. J Neurosci. 2007;27(9):2424–2432. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3886-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KJ, Makeig S, Hebb AO, Rao RP, denNijs M, Ojemann JG. “Cortical electrode localization from X-rays and simple mapping for electrocorticographic research: The Location on Cortex” (LOC) package for MATLAB. J Neurosci Methods. 2007;162(1–2):303–308. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KJ, Sorensen LB, Ojemann JG, den Nijs M. Power-law scaling in the brain surface electric potential. Plos Computational Biology. 2009;5(12):e1000609. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KJ, Zanos S, Fetz EE, den Nijs M, Ojemann JG. Decoupling the cortical power spectrum reveals real-time representation of individual finger movements in humans. J Neurosci. 2009;29(10):3132–3137. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5506-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollman HD, Haines SJ. Risk factors for postoperative neurosurgical wound infection. A case-control study. J Neurosurg. 1986;64(6):902–906. doi: 10.3171/jns.1986.64.6.0902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran D. Evolution of brain-computer interface: action potentials, local field potentials and electrocorticograms. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2010;20(6):741–745. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2010.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penfield W, Jasper HH. Epilepsy and the functional anatomy of the human brain. Boston, Little: 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Ramon C, Schimpf PH, Haueisen J. Influence of head models on EEG simulations and inverse source localizations. Biomed Eng Online. 2006;5:10. doi: 10.1186/1475-925X-5-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickert J, Oliveira SC, Vaadia E, Aertsen A, Rotter S, Mehring C. Encoding of movement direction in different frequency ranges of motor cortical local field potentials. J Neurosci. 2005;25(39):8815–8824. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0816-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouse AG, Moran DW. Neural adaptation of epidural electrocorticographic (EECoG) signals during closed-loop brain computer interface (BCI) tasks. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2009;2009:5514–5517. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2009.5333180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouse AG, Stanslaski SR, Cong P, Jensen RM, Afshar P, Ullestad D, Gupta R, Molnar GF, Moran DW, Denison TJ. A chronic generalized bi-directional brain-machine interface. J Neural Eng. 2011;8(3):036018. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/8/3/036018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouse AG, Williams JJ, Wheeler JJ, Moran DW. Cortical adaptation to a chronic micro-electrocorticographic brain computer interface. J Neurosci. 2013;33(4):1326–1330. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0271-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schalk G, Leuthardt EC. Brain-computer interfaces using electrocorticographic signals. IEEE Rev Biomed Eng. 2011;4:140–154. doi: 10.1109/RBME.2011.2172408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schalk G, McFarland DJ, Hinterberger T, Birbaumer N, Wolpaw JR. BCI2000: A general-purpose, brain-computer interface (BCI) system. Ieee Transactions on Biomedical Engineering. 2004;51(6):1034–1043. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2004.827072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schalk G, Miller KJ, Anderson NR, Wilson JA, Smyth MD, Ojemann JG, Moran DW, Wolpaw JR, Leuthardt EC. Two-dimensional movement control using electrocorticographic signals in humans. J Neural Eng. 2008;5(1):75–84. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/5/1/008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimoda K, Nagasaka Y, Chao ZC, Fujii N. Decoding continuous three-dimensional hand trajectories from epidural electrocorticographic signals in Japanese macaques. J Neural Eng. 2012;9(3):036015. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/9/3/036015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoshani J, Kupsky WJ, Marchant GH. Elephant brain. Part I: gross morphology, functions, comparative anatomy, and evolution. Brain Res Bull. 2006;70(2):124–157. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2006.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slutzky MW, Jordan LR, Krieg T, Chen M, Mogul DJ, Miller LE. Optimal spacing of surface electrode arrays for brain-machine interface applications. J Neural Eng. 2010;7(2):26004. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/7/2/026004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slutzky MW, Jordan LR, Lindberg EW, Lindsay KE, Miller LE. Decoding the rat forelimb movement direction from epidural and intracortical field potentials. J Neural Eng. 2011;8(3):036013. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/8/3/036013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenney JH, Vlahov D, Salcman M, Ducker TB. Wide variation in risk of wound infection following clean neurosurgery. Implications for perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis. J Neurosurg. 1985;62(2):243–247. doi: 10.3171/jns.1985.62.2.0243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres Valderrama A, Oostenveld R, Vansteensel MJ, Huiskamp GM, Ramsey NF. Gain of the human dura in vivo and its effects on invasive brain signal feature detection. J Neurosci Methods. 2010;187(2):270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2010.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treuting PM, Dintzis SM, Frevert CW, Liggitt HD, Montine KS. Comparative anatomy and histology : a mouse and human atlas. Amsterdam; Boston: Elsevier/Academic Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatraman S, Hendricks J, King ZA, Sereno AJ, Richardson-Burns S, Martin D, Carmena JM. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of PEDOT microelectrodes for neural stimulation and recording. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2011;19(3):307–316. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2011.2109399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Degenhart AD, Collinger JL, Vinjamuri R, Sudre GP, Adelson PD, Holder DL, Leuthardt EC, Moran DW, Boninger ML, Schwartz AB, Crammond DJ, Tyler-Kabara EC, Weber DJ. Human motor cortical activity recorded with Micro-ECoG electrodes, during individual finger movements. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2009;2009:586–589. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2009.5333704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JA, Felton EA, Garell PC, Schalk G, Williams JC. ECoG factors underlying multimodal control of a brain-computer interface. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2006;14(2):246–250. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2006.875570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]