Abstract

Background

To examine if the metabolic distress after traumatic brain injury (TBI) is associated with a unique proteome.

Methods

Patients with severe TBI prospectively underwent cerebral microdialysis for the initial 96 h after injury. Hourly sampling of metabolism was performed and patients were categorized as having normal or abnormal metabolism as evidenced by the lactate/pyruvate ratio (LPR) threshold of 40. The microdialysate was frozen for proteomic batch processing retrospectively. We employed two different routes of proteomic techniques utilizing mass spectrometry (MS) and categorized as diagnostic and biomarker identification approaches. The diagnostic approach was aimed at finding a signature of MS peaks which can differentiate these two groups. We did this by enriching for intact peptides followed by MALDI-MS analysis. For the biomarker identification approach, we applied classical bottom-up (trypsin digestion followed by LC-MS/MS) proteomic methodologies.

Results

Five patients were studied, 3 of whom had abnormal metabolism and 2 who had normal metabolism. By comparison, the abnormal group had higher LPR (1609 ± 3691 vs. 15.5 ± 6.8, P < 0.001), higher glutamate (157 ± 84 vs. 1.8 ± 1.4 μM, P < 0.001), and lower glucose (0.27 ± 0.35 vs. 1.8 ± 1.1 mmol/l, P < 0.001). The abnormal group demonstrated 13 unique proteins as compared with the normal group in the microdialysate. These proteins consisted of cytoarchitectural proteins, as well as blood breakdown proteins, and a few mitochondrial proteins. A unique as yet to be characterized peptide was found at m/z (mass/charge) 4733.5, which may represent a novel biomarker of metabolic distress.

Conclusion

Metabolic distress after TBI is associated with a differential proteome that indicates cellular destruction during the acute phase of illness. This suggests that metabolic distress has immediate cellular consequences after TBI.

Keywords: Traumatic brain injury, Microdialysis, Proteomics, Metabolic crisis, Biomarkers

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) results in an immediate cellular injury often consisting of a hemorrhagic injury and/or early cell death in a defined region of the brain. Secondary cellular injury resulting in cell loss occurs in regions that were not directly involved in the primary injury. Brain regions that are in metabolic distress during the early post-injury phase are more prone to long-term tissue atrophy [1]. The mechanisms involved that lead to metabolic distress and eventual tissue loss are as yet unknown. Better characterization of the metabolic distress state is needed in order to understand its significance.

Cerebral microdialysis has recently gained increased popularity as a clinical investigation monitor of brain metabolism after TBI [2–4]. Preliminary studies have outlined several neurochemical markers of metabolic distress after injury, including elevated glutamate, elevated glycerol, and elevated lactate/pyruvate ratio as well as low glucose concentrations. These markers tell us about the metabolic state of the tissue, but tell us little about the mechanisms leading to this distress. Conversely, microdialysis also is capable of measuring other non-metabolic compounds that may reflect important mechanisms of how cells survive or die. Proteomics is one method of analyzing microdialysis fluid and it may shed light on important processes associated with metabolic distress in human subjects. Formal assessments of the human proteome after TBI have recently been studied in CSF and blood [5–8], but assessment of changes in proteome based on metabolic state has heretofore not been addressed.

The purpose of this study is to initially characterize the differential proteome after TBI based on the metabolic state of the tissue. The metabolic state of the tissue is defined by the lactate/pyruvate ratio (LPR). In normal metabolic states, the LPR is <25 and in metabolic distress the LPR is >40. We have carefully analyzed five subjects in this report, three of whom are in metabolic distress and two of whom are not. Our proteomic methods enable us to evaluate the presence of protein fragments in the extracellular fluid despite the relatively limited membrane size of the microdialysis probe (i.e., 20 kD). We report the novel finding of a differential proteome including a specific peptide under the various pathological conditions leading to metabolic distress.

Materials and Methods

Patient Population

This study was approved by our institutional review board and was conducted as part of the UCLA Brain Injury Research Center in patients with traumatic brain injury. The main inclusion criteria were (1) a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of ≤8 or a GCS of 9–14 with computerized tomography (CT) brain scans demonstrating intracranial bleeding, and (2) the need for intracranial pressure monitoring. Surrogate informed consent was obtained. Over 2 years, five consecutive patients were enrolled and subsequently studied with continuous microdialysis monitoring and acute and long-term brain MRI.

TBI Treatment Protocol

This protocol has been previously outlined (9). All patients were admitted to the neurointensive care unit after initial stabilization in the emergency room or after surgery. Craniotomies were performed for evacuation of intracranial mass lesions and hematomas. Intracranial pressure was measured using a ventriculostomy and intracranial pressure (ICP) was maintained below 20 mmHg using a standardized treatment protocol including head of bed up to 30°, mild hyperventilation (PaCO2 = 30–35 mmHg), external ventriculostomy with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) drainage, moderate sedation with low doses of propofol, euglycemia (90–120 mg/dl), and maintenance of mild hypernatremia (sodium = 140–145 mmol/l). Refractory intracranial pressure was managed by pentobarbital-induced burst suppression coma. Cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) was kept above 60 mmHg with volume repletion and vasopressors. Continuous jugular venous oxygen saturation was monitored with SJO2 kept 60–70% through adjustments in CPP. Continuous electroencephalographic (EEG) monitoring was performed to assess the presence of seizure activity or to monitor the barbiturates effect when burst-suppression was induced.

Cerebral Microdialysis

The microdialysis catheter (10-cm flexible shaft, 10-mm membrane length, 20-kD cutoff, CMA microdialysis AB, Solna, Sweden) was inserted via a twist-drill burr hole adjacent to the preexisting ventriculostomy at a depth of 2–3 cm under the skin and at an angle of 30° anterior and lateral to the ventriculostomy catheter so that its tip was located in the frontal white matter. The microdialysis catheter was inserted in the right frontal lobe in 4/5 patients, with one placed on the right temporal lobe after removal of a traumatic hematoma on that side. The location of the microdialysis catheter was confirmed by computerized tomographic (CT) scan to be present in normal appearing white matter (Fig. 1). The microdialysis catheter was tunneled 3 cm under the skin and secured to the scalp with sutures. It was then attached to the perfusion pump (CMA 106 microdialysis pump, CMA microdialysis AB, Solna, Sweden). Normal saline was perfused through the catheter at a rate of 1 μl/min. Fluid in the samples was collected every hour, analyzed immediately on the CMA 600 for glucose, lactate, pyruvate, and glycerol and frozen in dry ice or in a freezer. We collected microdialysis hourly samples starting from post-injury hour 20 through post-injury hour 140. Repeat analysis was conducted within 4 weeks with stability of the results demonstrated for all analytes (R2 = 0.92). The concentration of four analytes (glucose, lactate, pyruvate, and glutamate) was measured in the automated analyzer (CMA 600 microdialysis analyzer, CMA microdialysis AB, Solna, Sweden). The concentration of each analyte was measured twice and the mean value used in the final analysis. Values were considered abnormal as follow: glutamate values above 5 μmol/l, lactate/pyruvate ratio (LPR) above 40, glucose values <0.20 mmol/l, and glycerol >50 μmol/l (16). Patients with LPR > 40 were designated as “abnormal” samples (Abn1, Abn2, Abn3) and patients with LPR < 40 were designated as “normal” samples (Nor1 and Nor2). For the proteomic studies outlined below, representative hourly samples of microdialysate from each patient were taken once every 4 h from the start of monitoring up to 84 h after injury or until the end of microdialysis monitoring.

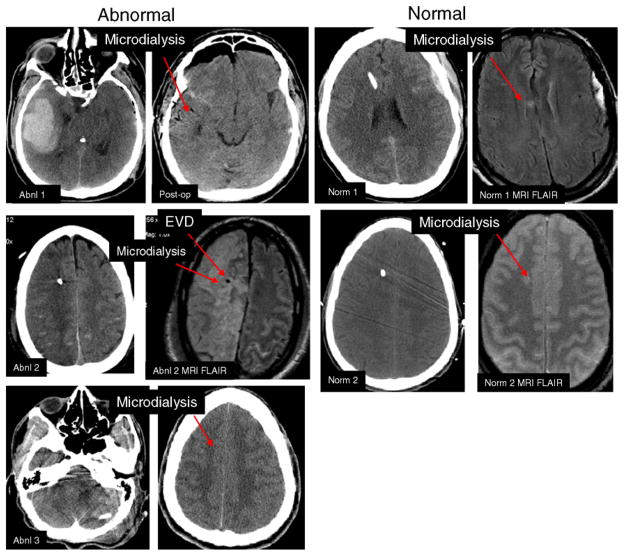

Fig. 1.

The computerized tomographic (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging of each patient. The three patients with elevated LPR are labelled as abnormal and the two with normal LPR are labelled normal. The arrow shows the locations of the microdialysis and the ventriculostomy (EVD). Each pair of images is labelled by patient

Imaging and Volumetric Analysis

Acute computerized tomographic (CT) imaging was performed using 0.5-cm slice thickness, non-contrast axial images. Acute and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed using Volumetric T1 Magnetization Prepared Gradient Echo (MPRAGE: TR 1900 ms, TE 3.5 ms, FOV 256 × 256, 1-mm slice thickness), axial fluid inversion recovery (FLAIR: TR 9590 ms, TE 70 ms, FOV 512 × 384, slice thickness 3 mm), axial gradient recalled echo axial (GRE: TR 1500 ms, TE 7 ms, FOV 512 × 384, slice thickness 3 mm). Microdialysis catheter location was verified on CT or MRI images. In normal subjects, the microdialysis catheter was contained within normal appearing white matter on MRI.

Proteomic Methods

Peptide Profiling with Magnetic Beads and Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization Time-Of-Flight (MALDI-TOF) MS

Peptides in the hourly microdialysate samples from each patient were enriched by binding to C18 magnetic beads. 5 μl of microdialysate sample was diluted with 65 μl of binding solution which has 5% acetonitrile (ACN) and 0.1% formic acid (FA), and mixed with 10 μl of 25 mg/ml C18 Dynabeads® (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The samples were incubated in a shaker for 20 min. The magnetic beads with the bound peptides were focused by placing a magnet externally to the sample tubes, and the supernatant which has the salts and other contaminants was removed. The beads were washed thrice with 80 μl of the binding solution. To elute the bound peptides, 10 μl of 50% ACN was added to the beads and mixed well. Approximately 5 μl of elute was mixed with 5 μl of MALDI matrix (7 mg/ml α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid in 70% ACN and 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid), and 2 μl was spotted onto the MALDI target plate in duplicates and analyzed by MALDI-MS (PerkinElmer-Sciex prOTOF MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer, Shelton, CT, USA). The instrument was calibrated externally using a peptide mixture (PepMix1, LaserBio Labs, Sophia-Antipolis Cedex, France) which has five different peptides with mass ranging from m/z 1000 to 2500. The laser intensity was set at 50%, and the acquisition mass window ranged from m/z 1500 to 15000. Spectra were collected using an automated data acquisition tool in the software, which irradiated each sample well with 100 shots of laser at 32 different spots and the data from all these spots were added to generate the accumulated mass spectrum. Mass spectra obtained from both abnormal and normal samples were compared to find peaks that are different between these two sample groups. Progenesis PG600 software (Nonlinear Dynamics, New-castle upon Tyne, UK) was used to recognize the differential peaks. PG600 aligns all the spectra from both groups and displays a ‘Simulated gel view’.

Pooling Microdialysate Samples

Initially, from each patient, 60 μl of microdialysate sample was collected every hour and from this 20 μl was removed for small molecule analysis and profiling with C18 beads. For further identification of proteins and peptides in the microdialysate, all the hourly timepoints were pooled to have one representative sample for each patient.

Tandem MS on Endogenous Peptides

To obtain sequence information of the peptides in the microdialysate sample, tandem MS (MS/MS) of the pooled microdialysate sample using a quadrupole time-of-flight (QTOF) mass spectrometer (Waters Synapt HDMS, Manchester, UK) was performed. Pooled samples were concentrated using our in-house made C18 microcolumns according to Gobom et al. [9]. In short, the microcolumns were fabricated with gel loading pipette tips (Eppendorf, Westbury, NY, USA) and Poros R2 (C18) stationary phase (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). After constricting the ends of the gel loading tip, C18 material was packed on these tips to achieve a 3–4-mm column length and equilibrated with 20-μl of 5% FA. 15 μl of each of abnormal subject #3 (Abn3) pool and Nor pool were diluted with 20 μl of 5% FA and loaded slowly on the column. The column was then washed with 20 μl of loading solvent and eluted directly into electrospray ionization (ESI) needles with 1 μl of 50% methanol and 1% FA. The collision energy for collisionally activated dissociation (CAD) MS/MS and the acquisition time were optimized for each targeted peptide to generate MS/MS spectra of sufficient quality. The spectra were processed using both MassLynx and MaxEnt3, and Mascot Distiller (Matrix Science, London, UK) to generate mass lists to search an in-house version of the Mascot search engine (Matrix Science). Additionally, the spectra were interpreted manually and the derived sequences searched against the NCBI database using BLAST.

Protein Digestion with Trypsin

To identify all the proteins present in the microdialysate, a classical proteomic bottom-up approach was undertaken. Protein concentration in the pooled samples was determined using MicroBCA protein assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). The protein concentration ranged from 0.15 to 0.19 μg/μl in the abnormal samples and from 0.08 to 0.13 μg/μl in the normal samples. To 10 μg of protein from each patient, 25 μl of 100% dimethyl sulfoxide (final concentration 10%) was added to denature the proteins. It was then digested with 0.5 μg of trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) in 50-mM ammonium bicarbonate buffer at 37°C overnight. After digestion, the samples were dried down, resuspended in 10 μl of 5% FA, and desalted using Omix C18 tips (Varian, CA, USA).

Protein Identification by Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)

LC-MS/MS was performed with a QTOF mass spectrometer (QSTAR Pulsar XL, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) equipped with a nanoelectrospray interface (Protana, Odense, Denmark) and a nano-HPLC system (Dionex/LC Packings, Sunnyvale, CA). For each LC-MS/MS run, 2 μg of the trypsin digest was resuspended in 6 μl of 0.1% FA and injected into the nano-LC equipped with a homemade precolumn (150 μm × 5 mm) and an analytical column (75 μm × 150 mm) packed with Jupiter Proteo C12 resin (particle size 4 μm, Phenomenex, Torrance, CA). The precolumn was washed with the loading solvent (0.1% FA) for 4 min before the sample was injected onto the LC column. The eluants used for the LC were 0.1% FA (solvent A) and 95% ACN containing 0.1% FA (solvent B). The flow rate was 200 nl/min, and the following gradient was used: 3–21% B in 36 min, 21–35% B in 14 min, 35–80% B in 4 min, and maintained at 80% B for 10 min. The column was finally equilibrated with 3% B for 16 min prior to the next run. All five patient samples were analyzed in triplicate. The tandem MS results from both the sample groups were searched against various databases (IPI human version 3.39, MSDB_06 and SwissProt) using MASCOT (Matrix Science) sequence search algorithm allowing for acetyl (N-term), formyl (N-term), oxidized methionine, carbamidomethylated cysteine, pyro-Glu (cyclization of N-terminal glutamine and glutamate), methyl (C-term), methylated aspartate and glutamate. The mass tolerance was set to 0.3 Da for both precursor and fragment ions. Also, a semi-tryptic search against IPI human database was included to account for endogenous peptides that were cleaved by trypsin. The results from all the searches were merged and recalibrated using our in-house developed Perl scripts. The query lists generated from the search results were converted to peptide/protein lists and grouped according to proteins that share peptides. Finally, the following criteria were used for generating a list of proteins that is present in each sample replicate:

The protein should be identified in at least two replicates (out of 3 total) in each patient.

If it is a single peptide match in the protein identified, peptide score should be more than 35.

If there are two or more peptide matches, peptide score should be more than 20.

Phosphopeptide Enrichment with TiO2 Microcolumns

Pooled abnormal and normal samples were enriched for phosphopeptides using in-house made titanium dioxide (TiO2) microcolumns. These microcolumns were made on P10 pipette tips using plugs of 3M Empore C8 extraction disks (3M Bioanalytical Technologies, St. Paul, MN, USA) to close the end of the tips. A 3–4-mm column length of TiO2 stationary phase was made using 4-μm TiO2 (GL Sciences Inc., Torrance, CA, USA). The column was equilibrated with 30 μl of 80% ACN, 3% trifluoroacetic acid. The samples were diluted four times in the same solvent used for equilibration and loaded slowly on the column, followed by a wash with the same solvent. The peptides were eluted step-wise using 2 μl of dd H2O, 10 μl of 1% ammonium hydroxide, and 2 μl of 40% ACN, 0.1% FA. 0.5 μl of elute and 0.5 μl of 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHB) matrix (10 mg/ml in 25% ACN, 15% isopropanol, 0.5% phosphoric acid) were spotted using dried droplet method on a MALDI target plate coated with lanolin. The spots were analyzed using MALDI-TOF MS (Voyager DE-STR, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

Dephosphorylation of Phosphopeptides Using Phosphatase

The phosphopeptides eluted from TiO2 microcolumns were dephosphorylated to confirm the phosphorylation. The peptides were dephosphorylated at pH 7.8 according to Larsen et al. [10]. Briefly, 1 μl of the TiO2 purified phosphopeptides was added into a plug of 20 μl of 0.05-U alkaline phosphatase in 50-mM ammonium bicarbonate in a C18 microcolumn. The top of the column was covered with parafilm and column was incubated at 37°C for 1 h. 10 μl of 5% FA was added to stop the reaction by acidification and the peptides were loaded onto C18 material. After washing with 5% FA, the peptides were eluted using 1 μl of DHB matrix and spotted on the MALDI target plate for analysis.

Phosphopeptide Identification by Tandem MS Using Synapt HDMS

To obtain phosphopeptide sequences, they were further purified using R3 oligo resin (Applied Biosystems) and fragmented using a QTOF mass spectrometer (Waters Synapt HDMS). Briefly, 1 μl of phosphopeptides eluted from TiO2 microcolumns was diluted with 20 μl of 5% FA and loaded slowly onto R3 oligo stationary phase, washed with 20 μl of 5% FA and eluted with 1 μl of 50% methanol and 1% formic acid directly into ESI needles. Spectra were acquired manually on the Synapt HDMS as described above.

Results

Clinical Characteristics

Five TBI patients were studied with microdialysis. Three subjects had metabolic distress and two did not. The injury characteristics are outlined in Table 1. The three patients with metabolic distress had the microdialysis probe in injured tissue, and had elevated ICP, whereas the remainder had microdialysis probe in normal appearing tissue. The injured tissue consisted of a secondary ischemic stroke due to traumatic internal carotid artery dissection, pericontusional tissue near an evacuated temporal contusion and hypoxic ischemic tissue due to hypotensive shock after TBI. Figure 1 outlines the probe location and tissue typing in the five patients.

Table 1.

Injury characteristics for each patient. GOSe 12 indicates the Glasgow outcome score extended at 12 months after injury

| Subject | Injury | MD location | MD tissue character | Sampling time | ICP elevation | GOSe 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abnl 1 | C-TBI | R Temporal | Pericontusional | PIH 43–106 | Y | 4 |

| Abnl 2 | C-TBI | R Frontal | Ischemia | PIH 29–80 | Y | 1 |

| Abnl 3 | GSW | R Frontal | Ischemia | PIH 19–67 | Y | 1 |

| Norm 1 | C-TBI | R Frontal | NAWM | PIH 60–108 | N | 8 |

| Norm 2 | C-TBI | R Frontal | NAWM | PIH 23–111 | N | 8 |

Metabolic Profile of Microdialysate

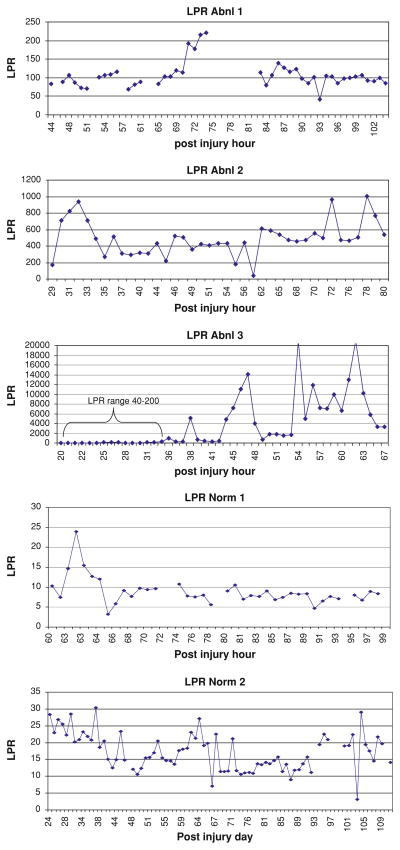

Three patients had persistent metabolic crisis during the observation period (Abnormal 1–3). The microdialysate data were analyzed using the mixed effects model for group, time, and interaction for group × time. During this period, the abnormal group had higher LPR (1609 ± 3691 vs. 15.5 ± 6.8, P < 0.001), higher glutamate (157 ± 84 vs. 1.8 ± 1.4 μM, P < 0.001), and lower glucose (0.27 ± 0.35 vs. 1.8 ± 1.1 mmol/l, P < 0.001). Glycerol values were similar in the two groups by the mixed model analysis despite higher mean values in the abnormal group (186 ± 120 vs. 21 ± 9, P < 0.11). The temporal pattern of microdialysis changes indicates that the maximum abnormality in the tissue was present within the initial 48 h after injury. Figure 2 shows the time course for the abnormal and normal patients. Table 2 outlines the mean microdialysis results for each group.

Fig. 2.

The time plot of hourly microdialysis lactate/pyruvate ratio for all five patients. The abnormal patients are solid and normal patients are open circles. Each patient is represented by a continuous stream of data points. The LPR values have been log transformed to be able to plot the time series

Table 2.

Microdialysis mean values are shown for each group

| Glucose (mmol/l) | Lactate (mmol/l) | Glutamate (μM) | Pyruvate (μM) | L/P ratio | Glycerol (μM) | Urea (μM) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abnl | 0.27 ± 0.30 | 3.25 ± 2.1 | 161 ± 73 | 23 ± 29 | 1530 ± 2141 | 186 ± 89 | 1.34 ± 1.2 |

| Norm | 2.3 ± .74 | 1.1 ± 0.5 | 1.4 ± 0.05 | 89 ± 9 | 13.5 ± 6.4 | 15 ± 7 | 1.37 ± 0.56 |

The values were all significantly different except glcyerol and urea

Initial Peptide Profiling Using MALDI-TOF MS

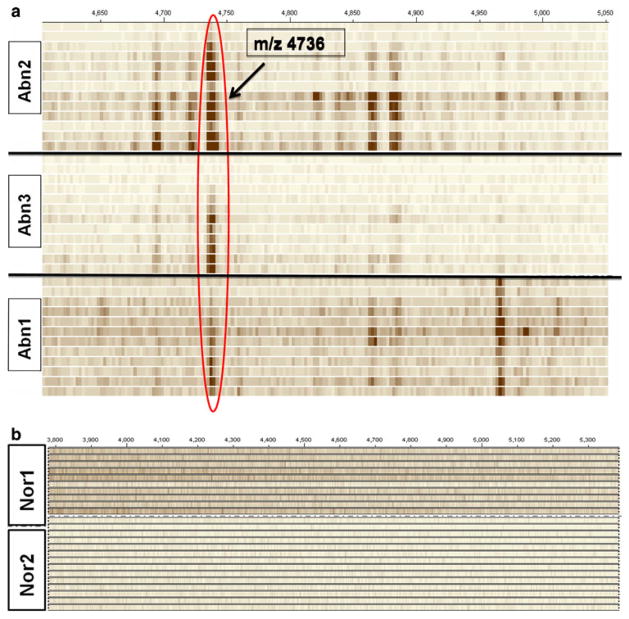

Using Progenesis PG600 to generate simulated gel views, the abnormal and normal patient profiles were reviewed. Each horizontal row in this gel view represents a mass spectrum obtained from the fluid collected at a certain time point (hours after injury) and profiled using magnetic beads coupled with MALDI-MS. The mass spectra of individual time points from all abnormal and normal samples are stacked separately to obtain the gel view shown in Fig. 3a, b, respectively. The mass spectra obtained from all three abnormal patients have a peak at m/z 4733.5. This peak is not present in both the normal LPR patients.

Fig. 3.

a, b The gel view of the mass spectra of abnormal and normal patients. The window shown is from m/z 4500–5000. The hyperdense band at m/z 4733.5 is seen in each of the abnormal patients and in none of the normal patients

Identification of Proteins Present in Microdialysate Samples

A total of 35 proteins were identified by LC-MS/MS in Abn1, 29 proteins in Abn2, and 26 proteins in Abn3. Compared to this, the number of proteins identified in the normal samples was relatively small; eight proteins were identified from Nor1 and 9 proteins from Nor2. Venn diagrams that illustrate the number of proteins uniquely present and those that are common between patients in both the sample groups were constructed (Fig. 4). Proteins present in at least two out of three patients in abnormal samples are listed in Table 3 and for normal samples in Table 4. All three abnormal samples have 13 proteins in common and there are 9 other proteins that are present in at least two out of three abnormal samples (Table 3). There are six proteins common to both the normal samples (Table 4), and three of these were present in all three abnormals as well. The proteins unique to each patient in both the sample groups were not included in the analysis because these proteins may represent individual variations specific to each patient. As one can see, there are a greater proportion of structural proteins seen in the metabolic distress group.

Fig. 4.

A Venn diagram showing the number of unique proteins for each subject and those proteins that were common among the abnormal and normal subgroups. The intersection shows the number of proteins that were in common

Table 3.

List of unique proteins present in at least two out of three abnormal samples

| Acc. No. | Description | Abn1 | Abn2 | Abn3 | No. of AA | MW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPI00410714 | Hemoglobin subunit alpha | X | X | X | 142 | 15258 |

| IPI00654755 | Hemoglobin subunit beta | X | X | X | 147 | 15998 |

| IPI00029717 | Isoform 2 of fibrinogen alpha chain | X | X | X | 644 | 69757 |

| IPI00021885 | Isoform 1 of fibrinogen alpha chain | X | X | X | 866 | 94973 |

| IPI00021907 | Isoform 1 of myelin basic protein | X | X | X | 304 | 33117 |

| IPI00220327 | Keratin, type II cytoskeletal 1b | X | X | X | 644 | 66039 |

| IPI00021440 | Actin, cytoplasmic 2 | X | X | X | 375 | 41793 |

| IPI00798155 | Ubiquitin | X | X | X | 106 | 12237 |

| FETUA_HUMAN | Alpha-2-HS-glycoprotein | X | X | X | 367 | 39325 |

| IPI00643115 | Stathmin | X | X | X | 116 | 13492 |

| IPI00220828 | Thymosin beta-4 | X | X | X | 44 | 5053 |

| IPI00220827 | Thymosin beta-10 | X | X | X | 44 | 5026 |

| IPI00012011 | Cofilin-1 | X | X | X | 166 | 18502 |

| IPI00025363 | Isoform 1 of glial fibrillary acidic protein | X | X | 432 | 49880 | |

| IPI00217465 | Histone H1.2 | X | X | 213 | 21365 | |

| IPI00298497 | Fibrinogen beta chain | X | X | 491 | 55928 | |

| IPI00021841 | Apolipoprotein A-I | X | X | 267 | 30778 | |

| IPI00793930 | Tubulin alpha | X | X | 335 | 37218 | |

| IPI00745872 | Albumin | X | X | 609 | 69367 | |

| IPI00883934 | Prothymosin alpha | X | X | 73 | 8161 | |

| IPI00008868 | Microtubule-associated protein 1B | X | X | 2468 | 270620 | |

| IPI00216461 | Acylphosphatase-2 | X | X | 127 | 13891 |

Listed is the number of amino acids (AA) and the molecular weight (MW) of the native, undigested protein. We identified only fragments of the native protein using the methods outlined above

Table 4.

List of proteins present in both normal samples

| Acc. No. | Description | No. of AA | MW |

|---|---|---|---|

| IPI00220327 | Keratin, type II cytoskeletal 1b | 644 | 66039 |

| IPI00029717 | Isoform 2 of fibrinogen alpha chain | 644 | 69757 |

| IPI00021885 | Isoform 1 of fibrinogen alpha chain | 866 | 94973 |

| IPI00607600 | Amyloid precursor-like protein 1 | 651 | 72247 |

| IPI00429366 | Programmed cell death 1 ligand 2 | 183 | 20867 |

| IPI00470716 | Isoform 2 of neuroendocrine protein 7B2 | 211 | 23659 |

Endogenous Peptides Identified by Tandem MS

The fragmentation spectra obtained from tandem MS experiments were processed using designated software and interpreted both manually and using the MASCOT search algorithm. Figure 5 shows the full-scan deconvoluted mass spectrum of pooled Abn3 sample eluted from C18 microcolumn, with the labeled peaks further identified by tandem MS experiments. The ions at m/z 997.49, 1195.62, and 1308.71 matched to a part of hemoglobin beta chain protein sequence with N-terminal variations as shown in Fig. 5 (inset). The m/z 1798.93 ion matched to a different stretch of amino acids within the same protein. The peptide at m/z 3039.54 matched to 30 amino acids from the N-terminus of the hemoglobin alpha chain and the m/z 2022.03 ion matched to 20 amino acids close to the C-terminus of the same polypeptide. Another cluster of four peptides (m/z 3326.67, 3342.66, 3358.64, and 3374.66) differing from one another by 16 Da also matched to first 32 residues from the N-terminus of hemoglobin alpha chain. The peptides at m/z 3342.66, 3358.64, and 3374.66 are singly, doubly, and triply oxidized forms of the m/z 3326.67 ion, respectively. In contrast, the full-scan mass spectra of normal sample (Fig. 6) eluted from C18 microcolumn does not have any of the peptides identified from the abnormal sample.

Fig. 5.

An example of deconvoluted mass spectra in the abnormal patients. The inset shows the list of peptides that matched to hemoglobin beta. Many more peaks are visible as compared with the normal subject in Fig. 6

Fig. 6.

An example of deconvoluted mass spectra in the normal patients

Phosphopeptide Enrichment, Confirmation, and Identification

Two phosphopeptides at m/z 1545.6 and 1616.6 were both present in all the pooled abnormal (Abn1, Abn2, and Abn3) samples enriched using TiO2 microcolumns (Fig. 7). None of these two peaks were present in pooled Nor1 sample and there is a small peak at m/z 1616.6 in the Nor 2 pool (Fig. 7). The dephosphorylation of these two phosphopeptides using alkaline phosphatase showed a 80 Da decrease in mass for both peaks, depicting the loss of the phosphate group (data not shown). The MS/MS spectra of the peptide ion at m/z 1616.6 matched to the published sequence of fibrinopeptide A and the peptide at m/z 1545.6 also matched to fibrinopeptide A missing the N-terminal alanine residue (Fig. 8).

Fig. 7.

The phosphopeptides at m/z 1545 and 1616 aligned from all abnormal and normal samples

Fig. 8.

Phosphopeptides at m/z 1616 and 1545 matched to fibrinopeptide A of fibrinogen alpha chain precursor protein. The difference between these two peptides is the alanine residue shown in box

Discussion

The principal findings of this study are (1) the extracellular fluid of TBI patients has a representative proteome that can be detected through microdialysis, (2) the proteome appears to be differentially affected with greater numbers of cytoskeletal proteins in those patients exhibiting extreme metabolic distress, and (3) there appears to be a novel peptide that as yet has not been well characterized. These results indicate that metabolic distress is accompanied by various levels of early proteolysis and that this proteolysis may be one mechanism through which long-term damage is done by metabolic distress.

Previous Proteomic Studies in TBI

Previously, a few groups have studied the proteome found in human serum [6, 7] or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) [8, 11, 12] after TBI. These studies have focused on a general description of the proteome or selective study of unique proteins as predictive biomarkers. A variety of cytoskeletal and neuronal proteins such as S100B, neuron-specific enolase (NSE), myelin-basic protein (MBP), and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) have been detected in these studies [13–15]. Interpretation of proteomic studies on serum is challenging since the proteins or proteolytic fragments from the damaged brain tissue are reabsorbed via the arachnoid villie into the blood [7] and this may lead to additional dilution effects.

Proteomic studies on cerebral microdialysis have been much more limited. The first description of proteomic study of microdialysis was by Maurer et al. [16], and was done in ischemic stroke patients using two dimensional gel electrophoresis followed by mass spectrometry and they found 10 proteins unique to the microdialysate sample. Surprisingly, some proteins identified in Maurer’s study were larger than 20 kD which is the stipulated cut-off of the microdialysate semi-permeable membrane. It could be that the folded three-dimensional structure of some of these proteins may allow for their retainment in the microdialysate sample. A more likely explanation is that fragments <20 kD of larger proteins are being identified using our methods. A more limited analysis of selective whole proteins in microdialysis, namely amyloid proteins have been done by Brody et al. [17] and Marklund et al. [18], using larger membrane (100 kD) catheters. In the Brody report, amyloid proteins appeared to be more prevalent under conditions of normal LPR and increasingly present as a function of time after injury. Marklund reported the presence of Tau and Aβ42 without specific comment about the state of metabolic distress. In neither study was a comprehensive approach performed to determine the range of potential proteins present nor the comparison of various metabolic states. In our study, we sought to explore the range of proteins that occur under conditions of metabolic distress rather than focus on one pathway.

Our main findings are that there is a differential set of proteins present in tissue that is under metabolic distress as compared with tissue that is metabolically more normal. The types of proteins that were found are variable in class but several of these proteins raise the possibility that particular chemical processes are occurring under conditions of metabolic distress. First, we see a wider array of cytoarchitectural proteins (i.e., keratin, actin, tubulin alpha, cofilin) as compared with the normal metabolic state. Stathmin is a protocongene that is important in the disassembly of microtubules in the cytoskeleton that can become active once upregulation of phosphorylation kinases are activated [19]. Thymosin beta 4 is a regulatory protein of actin, thereby regulating intracellular levels of actin. Presumably, metabolic distress leads to upregulation of these kinases and in turn may activate stathmin, leading to microtubular disassembly. It is interesting to consider the presence of cytoskeletal proteins together with the increased level of extracellular glycerol in these samples. Glycerol is a proposed biomarked of cell membrane integrity and increases under conditions of membrane breakdown. It is possible that the observed proteins reflect loss of cytoarchitecture and subsequent necrosis and exudation of cellular contents into the extracellular space. Secondly, we see the presence of acylphosphatase, which is a 98 amino acid enzyme that has a known role in mediating glycolysis, mediates the endoplasmic reticulum’s function in protein folding and unfolding, and can mediate formation of amyloid under experimental conditions. The presence of acylphosphatase may indicate compensatory responses in glycolysis and/or alteration of the protein folding/unfolding/ aggregation functions under conditions of metabolic distress. Activation of proteosome pathways may underlie that presence of multiple structural proteins in these samples. Hence, metabolic distress may trigger cytoskeletal disruption leading to the proteome that we have observed. This finding matches well with experimental reports of cytoskeletal disruption after TBI in which the calpain–calpastatin–caspase pathways are activated leading to cell death [20] and with proteomics performed on fresh whole brain pathological specimens after TBI [21].

In addition to cytoskeletal proteins, we found evidence of hematological peptides (hemoglobin subunit alpha and beta, fibrinogen alpha chain, and fibrinopeptide A) under conditions of metabolic distress. The presence of blood in the extracellular space could well explain this finding. However, this also raises the possibility that the presence of blood may have led to cellular toxicity through oxidative stress. Alternatively, microscopic bleeding could have resulted from the demise of tissue and be a secondary event rather than causative factor. Despite the presence of hematological peptides, the specific proteome in normal and abnormal subgroups were not representative of the blood proteome after TBI [21] hence we do not think this is related to blood brain barrier disruption alone.

Metabolic distress after TBI is characterized by a reduction in energy formation that may or may not occur in the context of ischemia. LPR has been correlated regionally with reduced oxidative metabolism [22]. The LPR is a good biomarker of metabolic distress. The duration of elevated LPR correlates with long-term regional atrophy [1]. Elevation of LPR for several days after TBI is associated with more severe atrophy of the frontal lobe, despite normal appearance of the frontal lobe on acute imaging. This suggests that there may be ongoing damage to normal appearing brain over time after the initial impact. The current proteomic data suggest that under extremely high LPR conditions, there is early loss of cellular integrity and proteolysis. This is a novel finding with regards to LPR and helps to underscore the importance of LPR as a biomarker in critically ill patients.

Limitations

This study is limited by several important features. First, the sample size is quite small but this was truly exploratory and a proof of concept rather than a definitive assessment of the proteome. Second, the small membrane pore size limits the sampling to fragments of larger proteins and/or small proteins. Use of a 100-kD probe may be better, but is also fraught with technical issues of requiring the perfusate fluid to contain macromolecules (dextran or albumin) which may in themselves affect proteomic sampling. Hence, the ideal methodology and catheter size for proteomics is unknown. Given the spectrum of sizes and the apparent proteolysis that occurred, rendering fragments of large proteins capable of being dialyzed via the small pore size, we are not certain that a bigger pore size is really necessary. Thirdly, we were not able to identify the novel protein at m/z 4733.5. This analysis requires more fluid than we had remaining. We anticipate needing an additional 600 μL of fluid to this. Hence, we have more work to do to evaluate if this is truly unique and what potential biological role it plays.

Conclusions

The evaluation of small molecular weight peptides is feasible using cerebral microdialysis. Tissue under metabolic distress displays a reproducible and unique proteome as compared with normal appearing TBI tissue. The proteome suggests ongoing cytoarchitectural disruption that may be mediated by proteosomal activity.

Contributor Information

R. Lakshmanan, UCLA Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, USA

J. A. Loo, UCLA Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, USA

T. Drake, UCLA Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, USA

J. Leblanc, UCLA Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, USA

A. J. Ytterberg, UCLA Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, USA

D. L. McArthur, UCLA Department of Neurosurgery and Neurology, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center, 757 Westwood Blvd, Room, RR 6236A Los Angeles, CA, USA

M. Etchepare, UCLA Department of Neurosurgery and Neurology, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center, 757 Westwood Blvd, Room, RR 6236A Los Angeles, CA, USA

P. M. Vespa, Email: PVespa@mednet.ucla.edu, UCLA Department of Neurosurgery and Neurology, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center, 757 Westwood Blvd, Room, RR 6236A Los Angeles, CA, USA

References

- 1.Marcoux J, McArthur DA, Miller C, Glenn TC, Villablanca P, Martin NA, et al. Persistent metabolic crisis as measured by elevated cerebral microdialysis lactate-pyruvate ratio predicts chronic frontal lobe brain atrophy after traumatic brain injury. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:2871–7. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318186a4a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bullock R, Zauner A, Woodward JJ, Myseros J, Choi SC, Ward JD, et al. Factors affecting excitatory amino acid release following human head injury. J Neurosurg. 1998;89:507–18. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.89.4.0507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vespa M, Prins M, Ronne-Engstrom E, Caron M, Shalmon E, Hovda DA, et al. Increase in extracellular glutamate caused by reduced cerebral perfusion presure and seizures after human traumatic brain injury: a microdialysis study. J Neurosurg. 1998;89:971–82. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.89.6.0971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hillered L, Vespa PM, Hovda DA. Translational neurochemical research in acute human brain injury: the current status and potential future for cerebral microdialysis. J Neurotrauma. 2005;22:3–41. doi: 10.1089/neu.2005.22.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pineda JA, Wang KK, Hayes RL. Biomarkers of proteolytic damage following traumatic brain injury. Brain Pathol. 2004;14:202–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2004.tb00054.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berger RP. The use of serum biomarkers to predict outcome after traumatic brain injury in adults and children. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2006;21:315–33. doi: 10.1097/00001199-200607000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haqqani AS, Hutchison JS, Ward R, Stanimirovic DB. Biomarkers and diagnosis; protein biomarkers in serum of pediatric patients with severe traumatic brain injury identified by ICAT-LC-MS/MS. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24:54–74. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.0079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gao WM, Chadha MS, Berger RP, Omenn GS, Allen DL, Pisano M, et al. A gel-based proteomic comparison of human cerebrospinal fluid between inflicted and non-inflicted pediatric traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24:43–53. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.0061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gobom J, Nordhoff E, Mirgorodskaya E, Ekman R, Roepstorff P. Sample purification and preparation technique based on nano-scale reversed-phase columns for the sensitive analysis of complex peptide mixtures by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry. J Mass Spectrom. 1999;34(2):105–16. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9888(199902)34:2<105::AID-JMS768>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larsen MR, Sørensen GL, Fey SJ, Larsen PM, Roepstorff P. Phospho-proteomics: evaluation of the use of enzymatic de-phosphorylation and differential mass spectrometric peptide mass mapping for site specific phosphorylation assignment in proteins separated by gel electrophoresis. Proteomics. 2001;1(2):223–38. doi: 10.1002/1615-9861(200102)1:2<223::AID-PROT223>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zuberovic A, Wetterhall M, Hanrieder J, Bergquist J. CE MALDI-TOF/TOF MS for multiplexed quantification of proteins in human ventricular cerebrospinal fluid. Electrophoresis. 2009;30:1836–43. doi: 10.1002/elps.200800714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanrieder J, Wetterhall M, Enblad P, Hillered L, Bergquist J. Temporally resolved differential proteomic analysis of human ventricular CSF for monitoring traumatic brain injury biomarker candidates. J Neurosci Methods. 2009;177:469–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lumpkins KM, Bochicchio GV, Keledjian K, Simard JM, McCunn M, Scalea T. Glial fibrillary acidic protein is highly correlated with brain injury. J Trauma. 2008;65:778–82. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318185db2d. discussion 782–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zemlan FP, Jauch EC, Mulchahey JJ, Gabbita SP, Rosenberg WS, Speciale SG, et al. C-tau biomarker of neuronal damage in severe brain injured patients: association with elevated intracranial pressure and clinical outcome. Brain Res. 2002;947:131–9. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02920-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Afinowi R, Tisdall M, Keir G, Smith M, Kitchen N, Petzold A. Improving the recovery of S100B protein in cerebral microdialysis: implications for multimodal monitoring in neurocritical care. J Neurosci Methods. 2009;181:95–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2009.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maurer MH, Berger C, Wolf M, Futterer CD, Feldmann RE, Jr, Schwab S, et al. The proteome of human brain microdialysate. Proteome Sci. 2003;1:7. doi: 10.1186/1477-5956-1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brody DL, Magnoni S, Schwetye K, Spinner ML, Esparza TL, Stocchetti N, et al. Science. 2008;321:1221–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1161591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marklund N, Blennow K, Zetterberg H, Ronne-Engstrom E, Enblad P, Hillered L. Monitoring of brain interstitial total tau and beta amyloid proteins by microdialysis in patients with traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurgery. 2009;110:1227–37. doi: 10.3171/2008.9.JNS08584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cassimeris L. The oncoprotein 18/stathmin family of microtubule destabilizers. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002;14(1):18–24. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(01)00289-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ottens AK, Kobeissy F, Golden E, Ahang A, Haskins W, Chen S, et al. Neuroproteomics in neurotrauma. Mass Spec Rev. 2006;25:380–408. doi: 10.1002/mas.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang X, Yang S, Wang J, Zhang X, Wang C, Hong G. Expressive proteomics profile changes of injured human brain cortex due to acute brain trauma. Brain Injury. 2009;23:830–40. doi: 10.1080/02699050903196670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vespa P, Bergsneider M, Hattori N, Wu HM, Huang SC, Martin NA, et al. Metabolic crisis without brain ischemia is common after traumatic brain injury: a combined microdialysis and positron emission tomography study. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2005;25:763–74. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]