Abstract

The recent findings in several species that primary auditory cortex processes non-auditory information have largely overlooked the possibility for somatosensory effects. Therefore, the present investigation examined the core auditory cortices (anterior – AAF, and primary auditory-- A1, fields) for tactile responsivity. Multiple single-unit recordings from anesthetized ferret cortex yielded histologically verified neurons (n=311) tested with electronically controlled auditory, visual and tactile stimuli and their combinations. Of the auditory neurons tested, a small proportion (17%) was influenced by visual cues, but a somewhat larger number (23%) was affected by tactile stimulation. Tactile effects rarely occurred alone and spiking responses were observed in bimodal auditory-tactile neurons. However, the broadest tactile effect that was observed, which occurred in all neuron types, was that of suppression of the response to a concurrent auditory cue. The presence of tactile effects in core auditory cortices was supported by a substantial anatomical projection from the rostral suprasylvian sulcal somatosensory area. Collectively, these results demonstrate that crossmodal effects in auditory cortex are not exclusively visual and that somatosensation plays a significant role in modulation of acoustic processing and indicate that crossmodal plasticity following deafness may unmask these existing non-auditory functions.

Keywords: Crossmodal, Tactile, Auditory, Vision, Deaf, Plasticity

INTRODUCTION

A well-known neurological phenomenon occurs when a major sensory system is lost, particularly if the insult occurs at an early age. Termed ‘crossmodal plasticity,’ this effect essentially replaces the lost sensory inputs with those from the remaining, intact senses. In some instances, the performance of the intact modalities becomes enhanced, or supranormal, and such ‘compensatory effects’ have a long and rich cultural history expressed through blind poets and musicians. Although a great deal of information about compensatory plasticity is anecdotal, there is a growing interest in identifying the neural bases underlying the phenomenon and several mechanisms for its occurrence have been advanced (Rauschecker, 1995; Bavalier and Neville, 2001). It has been proposed that, following major sensory loss, crossmodal plasticity results from (1) the ingrowth of connections from new sources among the intact sensory representations and/or (2) the unmasking or re-weighting of existing ‘silent’ connections. Interestingly, recent studies showed that the first proposed mechanism is unlikely, since neither ferrets (Allman et al., 2009a; Meredith and Allman, 2012) nor cats (Kok et al., 2014; Barone et al., 2013;) reveal substantial new projections to deaf auditory cortices. At virtually the same time, multiple reports have emerged that document the presence of non-auditory effects within auditory cortical regions of hearing animals (Bizley et al., 2007; Bizley and King, 2009; Ghazanfar et al., 2005; Kayser and Logothetis, 2007; Kayser et al., 2005;2008; 2009; Meredith et al., 2012). Thus, these collective results strongly indicate that deafness-induced crossmodal plasticity can result from the reweighting of connections that are already present within the cortices of hearing individuals.

The literature about the nature of cortical crossmodal effects following deafness is overwhelmingly dominated by visual effects. Deaf individuals exhibit supranormal performance in a variety of visual tasks, including detection of and orientation to peripheral stimuli as well as detection of visual motion (Bavelier et al., 2006). Similarly, deaf cats show supranormal detection of peripheral visual targets and visual motion (Lomber et al., 2010). Consistent with these visually-guided behaviors, neurons in specific auditory cortical regions of deaf animals have revealed visually-driven activity, such as mouse primary auditory cortex (A1-Hunt et al., 2006), cat anterior auditory field (AAF-Meredith and Lomber, 2012), cat auditory field of the anterior ectosylvian sulcus (FAES-Meredith et al., 2011) and human auditory cortex (Finney et al., 2001; Cardin et al., 2013). These visual effects in auditory cortex, however, do not appear de novo after deafness, but are present within auditory cortex of hearing animals, as demonstrated by numerous studies in several species (Bizley et al., 2007; Bizley and King, 2009; Ghazanfar et al., 2006; Kayser and Logothetis, 2007; Kayser et al., 2008; 2009; Meredith et al., 2012). These collective findings support the postulate that, because visual inputs influence auditory processing in hearing individuals, these visual inputs “unmask” or increase their synaptic weighting (and/or number) following hearing loss. This notion is further supported by the fact that dendritic spine density and spine head diameter significantly increase as a result of crossmodal plasticity in auditory cortex of early deaf cats (Clemo et al., 2014).

Although the role of vision in crossmodal compensatory phenomena following deafness is well established, the role of somatosensation in this phenomenon has only recently begun to be evaluated. Despite the well-known convergence of somatosensory inputs at multiple sites within the ascending auditory pathway (Aitkin et al., 1986; Kanold and Young, 2001; Kanold et al., 2011; Shore et al., 2000; 2003; Basura et al., 2012), few cortical investigations have expected or evaluated the somatosensory modality in relation to deafness-induced crossmodal plasticity. Among these rare studies are the detection of tactile effects within auditory cortex of early deaf humans (Auer et al., 2003; Karns et al., 2012) and the single-unit recording studies of ferrets with hearing loss. In fact, core auditory cortex (areas A1 and AAF) of ferrets with early hearing loss (Meredith and Allman, 2012), late hearing impairment (Meredith et al., 2012) and late deafness (Allman et al., 2009a) demonstrate crossmodal effects that are dominated by somatosensation. These same studies also indicate that the observed crossmodal effects were not accompanied by the ingrowth of new or expanded projections from somatosensory regions. What is not known, however, is whether these somatosensory effects are novel properties that somehow arise as a consequence of hearing loss, or if somatosensory effects are already present within the core auditory cortices of normal, hearing ferrets that are “unmasked” by deafness. There is evidence for somatosensory effects in auditory cortex of normal hearing subjects, but studies in humans and primates provide conflicting evidence for its occurrence within core versus belt areas (Foxe et al., 2000; 2002; Kayser et al. 2005; 2009; Schurmann et al., 2006; Nordmark et al., 2012; Hoefer et al., 2013). Therefore, the goal of the present study is to examine the core auditory cortices of hearing ferrets for influences and inputs from the somatosensory system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All procedures were performed in compliance with the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Institutes of Health, publication 86-23), the National Research Council's Guidelines for Care and Use of Mammals in Neuroscience and Behavioral Research (2003), and with prior approval by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Virginia Commonwealth University.

Surgical Procedures

Each ferret (adult, male; n=5) was surgically prepared for electrophysiological recording 2-3 days before the data collection procedure. Under aseptic conditions and pentobarbital anesthesia (40 mg/kg, i.p.), the animal's head was secured in a stereotaxic frame and a craniotomy was opened to expose the auditory cortices. A stainless steel head-support device was implanted over the opening and the scalp was closed around the implant. Following surgery, standard postoperative care was provided.

Electrophysiological Recording

For recording, the ferret was anesthetized (35 mg/kg Ketamine; 2 mg/kg Acepromazine) and the implanted well was secured to a supporting bar that elevated and fixed the position of the head. The animal was intubated through the mouth, ventilated and its expired CO2 was monitored and kept near 4.5%. Fluids and supplemental anesthetics (4 mg/kg/h Ketamine; 0.5 mg/kg/h Acepromazine) were delivered continuously using an infusion pump. Because it was essential that the animal's body remained motionless during the lengthy sensory tests (described below), a muscle relaxant (Pancuronium bromide, induction: 0.3 mg/kg i.p.; supplemental dose: 0.2 mg/kg/h) was administered. Heart rate, blood oxygen levels and body temperature were continuously monitored and a circulating-water heating pad was used to maintain temperature.

The implanted recording well was opened and the dura mater overlying the core auditory region was opened. A 32-channel electrode (~1 MΩ, A4×8-5mm-200-200-413 or A1×32×5mm #100-413, NeuroNexus Technologies, Ann Arbor, MI) was positioned, using gyral/sulcal landmarks, in auditory cortex to a depth of ~2mm. Neuronal activity was routed through the headstage and chained Medusa-16 preamps (digitized at 25kHz) into a Pentusa digital amplifier (Tucker-Davis Technologies 32 channel recording system) and displayed on computer. At each recording site, neurons were screened for responses to an extensive battery of manually-presented stimuli that included auditory (clicks, claps, whistles and hisses), visual (flashed or moving light or dark stimuli), and somatosensory (gentle air puffs, brush strokes and taps, manual pressure and joint manipulation, and taps using calibrated Semmes-Weinstein filaments) stimuli.

Following manual assessment of sensory responsiveness, quantitative sensory tests were performed that consisted of computer-triggered auditory, visual and somatosensory stimuli, presented alone and in combination. Free-field auditory cues were electronically-generated white-noise bursts (100 ms) from a speaker 44 cm from the head in contralateral space (45° azimuth/ 0° elevation; 70 dB SPL). Visual cues were projected onto a translucent hemisphere (92 cm diameter) of which the movement direction, velocity and amplitude were computer-controlled. Because it usually was not possible to map visual receptive fields, a standard visual stimulus was used that consisted of a vertically-oriented bar of light (~2×10°) that moved 30° from nasal-to-temporal in the upper quadrant of contralateral visual space (see also Allman et al. 2008). An electronically-driven, modified shaker (Ling, 102A), with independently programmable amplitude and velocity settings provided focal somatosensory stimulation through a calibrated (1g) 5cm nylon filament. This electro-motive device is essentially noiseless. As a further control for any possible acoustic emissions, each set of somatosensory tests was followed by a sham test in which the device remained in place, but the filament was disengaged from contact with the body surface. Only those neurons activated by the stimulus engaged with the body surface, but not activated by the sham trial, were designated as tactile. For testing, the tactile stimulus was placed within the manually mapped somatosensory receptive field; if no receptive field was apparent, the stimulus was placed on the side of the face, which was the location of highest probability observed in deaf ferrets (Allman et al. 2009a). During the combined-modality presentations, the visual stimulus preceded the auditory and somatosensory cues by 50 ms to roughly compensate for the response latency differences of the different modalities (Allman et al. 2008). Each stimulus iteration was separated by 3-7 s, and each condition was presented 50 times. For data collection, neuronal responses were digitized at 25 kHz using a Tucker Davis neurophysiology workstation (System III, Alachua, FL) and stored of a PC for later analysis.

Electrophysiological data analysis

Individual neuronal waveforms were sorted offline using an automated Bayesian sort-routine (v. 2.10, OpenSorter, Tucker Davis) to identify and group waveforms representing single units, as depicted in Figure 1. For each neuronal template, responses to stimuli were identified after the method of Bell et al. (2001): response onset was defined as the point which activity level exceeded 3 standard deviations above median spontaneous activity (as measured from −0.5 s to 5 ms prior to stimulus onset), with a minimum of 15 ms of activity sustained at that level; response offset was defined as activity that dropped below the sustained response level and remained below it for 15 ms; response duration was defined as the period between the response onset and offset. The time span between onset and offset was used to calculate the spike counts evoked by sensory stimulation and, in this manner, a mean (and standard deviation) spike count was determined for somatosensory, auditory, visual and combined-modality stimulation for each neuron. An activity of >0.5 mean spikes per trial in response to at least one stimulus permutation was required to qualify as a suprathreshold response. Because it is possible that the activity of a neuron might be recorded from multiple neighboring recording sites, t-tests were used to assess whether stimulus-evoked spike counts recorded at adjacent sites were the same; if responses were statistically similar amongst the neurons that were compared, data from the neuron with the strongest unisensory response was included for analysis. Finally, to assess the multisensory and integrative properties of a neuron, a paired t-test was used to assess if each separate-modality response (auditory alone, visual alone, tactile alone) differed significantly from the combined condition (auditory-visual together, auditory-tactile together, auditory-visual-tactile together). Unisensory neurons were defined as those which were influenced by only one sensory modality. Multisensory neurons activated (e.g., suprathreshold spiking that is time-locked to stimulus onset) by two different sensory modalities were defined as bimodal; those activated by three were identified as trimodal neurons. Multisensory neurons activated by only one modality but whose response could be modulated (suppressed or facilitated) by a second, otherwise ineffective modality were defined as subthreshold neurons (Allman et al. 2009b). These quantitative criteria were applied to neuronal responses obtained and, given that the same stimulation and recording paradigms were used, bias toward identification of a particular neuron type was minimized.

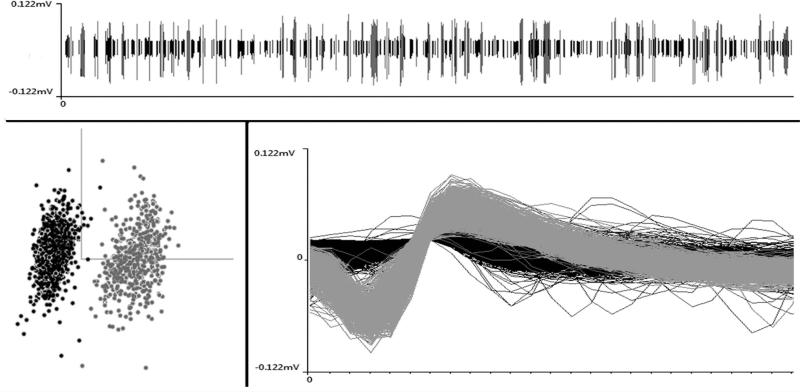

Figure 1.

A screen-shot of waveforms recorded over an extended epoch from one site in A1to demonstrate (top) the raw signals after thresholding, (bottom-left) cluster-cutting plot and (bottom-right) waveform discrimination for identification of single-unit activity (white=1 unit; grey=2ndunit).

The depth/position of each neuron within a penetration was noted and correlated with its various measures of sensory responsiveness in a data table. Multiple recording penetrations were attempted in each animal. At the conclusion of the experiment, the animal was euthanized and the brain was fixed, blocked and serially sectioned. The sections were processed using standard histological procedures and a projecting microscope was used to make scaled reconstructions of the recording penetrations. Auditory cortical fields of A1 (primary), AAF (anterior auditory field), were identified by sulcal landmarks according to the criteria of Bizley et al. (2005). Because the borders between the auditory fields on the middle ectosylvian gyrus and the visual or somatosensory fields in the adjacent suprasylvian sulcus (e.g., anterolateral and posterolateral suprasylvian visual areas, Manger et al. 2008; lateral rostral suprasylvian somatosensory area, Keniston et al. 2008) have not been defined, only those neurons histologically verified within the gyral aspects of the cortical mantle were included in the present evaluation of core auditory cortex (areas A1 and AAF).

Connectivity/tracer experiments

The cortical sources of inputs to the core auditory regions (A1/AAF) was examined in adult ferrets (n=4, male; post-injection transport time average=12.6 days). In a subsequent set of experiments, the orthograde projections to A1from the ferret lateral rostral suprasylvian cortical region was examined (n=5, adult, male; post-injection transport time average=8.4 days). Both experiments used the same procedures. Using pentobarbital anesthesia (40 mg/kg i.p.) under aseptic surgical conditions, a small craniotomy was made to expose the desired cortical region. Biotinylated dextran amine (BDA; 10k/3k MW 50:50 mixture, 10% in citrate buffer) was pressure injected (0.8-1.5 μl volume) from a 5 μl Hamilton syringe into the targeted region using gyral/sulcal landmarks. After the period for tracer transport, the animal was euthanized, perfused (saline) and fixed (4% paraformaldehyde). The brain was removed, blocked stereotaxically and sectioned (50μm thick) in the coronal plane. Sections were processed using a standard BDA protocol (Veenman et al., 1992) with metal intensification, mounted on slides and coverslipped without counterstain. The processed sections were digitized using Neurolucida software (MBF Biosciences, Williston, VT) to document the tissue outline, grey-white border, and the location of labeled neuronal cell bodies and/or axon terminals. Functional maps of ferret cortex and thalamus (Leclerc et al., 1993; Rice et al., 1993; McLaughlin et al., 1998; Manger et al., 2002a, b, 2005, 2008; Ramsay and Meredith, 2004; Bizley et al. 2007; Keniston et al., 2009; 2009; Foxworthy and Meredith, 2011) were used to identify the regions containing labeled neuronal profiles. The NeuroLucida software was also used to count the number of labeled neurons, or labeled axon terminals, within identified cortical regions. Selected section tracings were converted to a standard graphics program for visualization and display.

RESULTS

Non-auditory Neurons

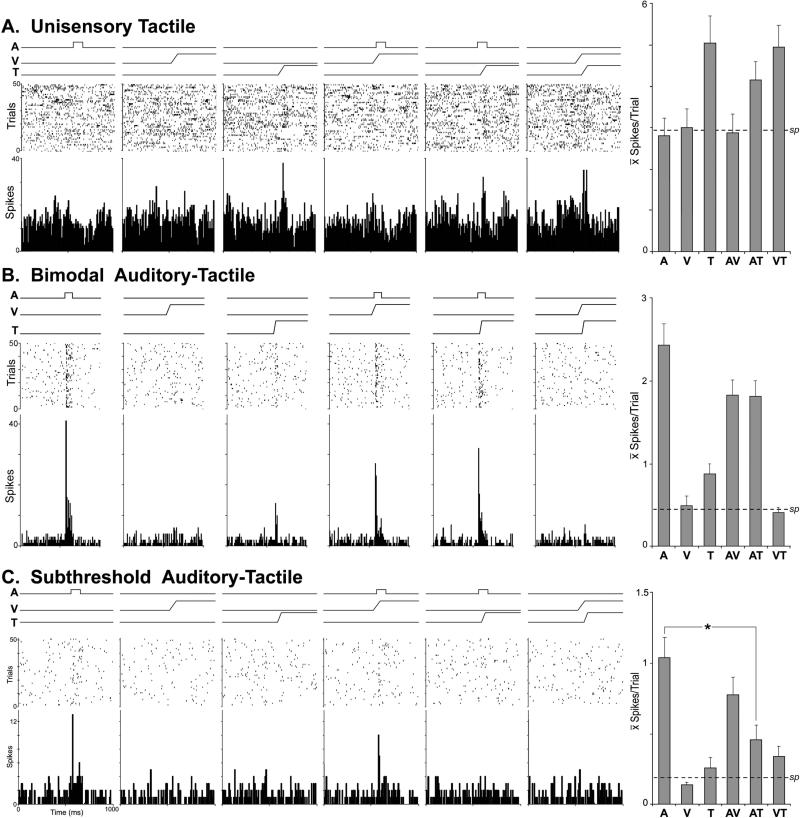

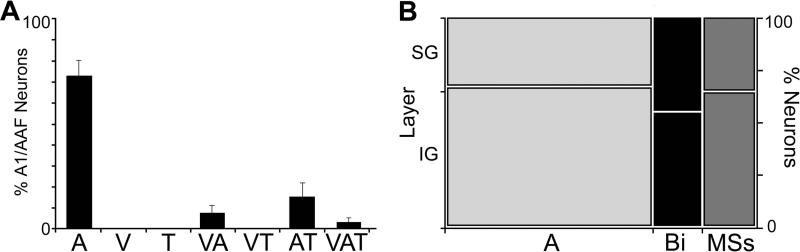

A total of 311 core auditory cortical neurons in hearing ferrets (n=5; male; 1.4-1.8 kg; >130 days old) were examined for their responses to multiple sensory stimuli and their combinations. All were confirmed, by histological reconstruction, to reside within the A1/AAF region (see Figure 2). Of the responsive neurons, nearly all (99.7%; 310/311) were activated by auditory stimulation that generated an overall sample average of 4.17 spikes/trial ± 0.24 s.e. Non-auditory cues (tactile, visual) were also observed to be effective for some neurons. For example, the neuron depicted in Figure 3A was activated by tactile stimulus (on contralateral forepaw) and this response was not significantly influenced by the presence of other sensory cues (visual, auditory). However, this was the only example of a unisensory tactile neuron that was encountered and it is possible that an effective auditory stimulus was not identified during its period of examination. More commonly observed were neurons affected by more than one sensory modality, as illustrated in Figure 3B. Here, a neuron is depicted that met the definition of a bimodal multisensory neuron, since it was activated by an auditory stimulus (presented alone) and by a tactile stimulus (presented alone). Another type of multisensory neuron found was like the one depicted in Figure 3C, which was activated only by an auditory stimulus, but that response was significantly (p<0.05; paired t-test) suppressed when combined with a tactile cue. This pattern of response corresponds with the subthreshold form of multisensory neuron. It is important to note that all neurons characterized as subthreshold multisensory exhibited an excitatory response to auditory stimulation that was modulated by the presence of non-auditory stimuli that seemed ineffective when presented alone. In total, approximately 26% (n=108/311) of the core auditory cortical neurons were influenced (either excited or modulated) by non-auditory stimulation, as summarized in Figure 4A and Table 1. Of these non-auditory effects, approximately 17.7% (n=55/311) were due to visual inputs (also described by Bizley et al., 2007, Bizley and King, 2009). Observed somewhat more frequently were tactile effects, which significantly influenced nearly 23% (n=71/311) of the neurons examined. As has been observed in other studies (Bizley et al., 2007; Foxworthy et al., 2013), evoked levels of activity varied between unisensory and multisensory (bimodal and subthreshold forms) neurons. On average, responses to the broadband auditory stimulus was significantly (t-test; p<0.001) lower among unisensory neurons (average=3.5 spikes/trial ± 0.2 s.e.) versus that elicited from multisensory neurons (average= 5.3 spikes/trial ±0.56 s.e.), and this trend applied to similar differences in spontaneous activity as well. As graphed in Figure 4B, an analysis of the laminar distributions of these different neuron types did not reveal differences between their supragranular and infragranular incidences.

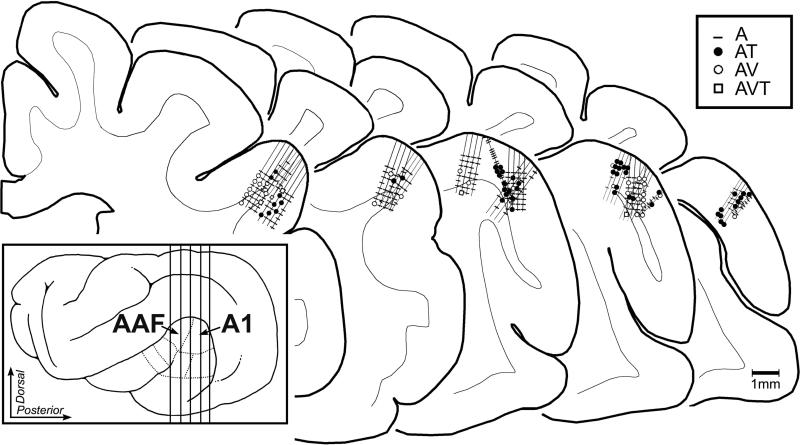

Figure 2.

Location of core auditory cortices of Anterior auditory field (AAF) and Primary auditory field (A1) on a lateral view of the ferret brain (inset; functional divisions indicated by dotted lines from Bizley et al., 2005) and the histological reconstruction of recording penetrations within those regions. Vertical lines on lateral view of cortex (inset) indicate approximate level from which the enlarged coronal sections were derived. The long straight lines indicate the location of an electrode shaft and the cross-hash or marks indicate the location of a recorded neuron. Each mark indicates one neuron and the Key indicates the sensory response type (A=auditory; AT=auditory-tactile; AV=auditory-visual; AVT= auditory-visual-tactile; not all neurons are plotted due to overlap. Recording penetrations that entered the banks of the suprasylvian sulcus (where visual and somatosensory representations have been identified) were excluded.

Figure 3.

Single-unit recordings from neurons in core auditory cortex of hearing ferrets in response to auditory (A), visual (V), tactile (T) stimuli and their combinations (AV, AT, and VT). Each of the data panels indicate stimulus traces (top lines), rasters (1 dot=1 spike; 1 row= 1 presentation) and histograms (10ms time bin). In part A, this neuron was responsive only to the tactile stimulus and its effectiveness was not significantly influenced by the presence of an auditory or visual cue (a unisensory tactile neuron), as summarized in the bar graph (far right). In part B, the neuron was activated by an auditory stimulus and by a tactile stimulus presented alone (a bimodal neuron), and the activity levels were diminished when the two stimuli were combined, as summarized in the bar graph (far right). In part C, this neuron was activated by an auditory stimulus, but none of the other stimuli presented alone. However, when the auditory stimulus was combined with a tactile cue, the response was significantly (asterisk) diminished, as summarized in the bar graph (far right). In each graph, the dashed line indicates the level of spontaneous (sp) activity.

Figure 4.

Part (A): The pattern and proportion (mean ± se) of sensory responsiveness for neurons from core auditory cortices of hearing ferrets. A=unimodal auditory; V=unimodal visual; T=unimodal tactile; VA=influenced by visual and auditory stimuli; VT=influenced by visual and tactile stimuli; AT=influenced by auditory and tactile stimuli; VAT=influenced by all three stimulus modalities. Part (B): The proportion of unisensory auditory neurons (A – light gray), bimodal (Bi – Black) and Subthreshold Multisensory (MSs- gray) that were identified in supragranular (SG) or infragranular (IG) laminar locations of core auditory cortex.

Table 1.

Based on their responses to separate and combinations of auditory, visual and tactile stimuli, the neurons identified within ferret core auditory cortex were grouped into one of three major categories: Unisensory (Uni), Bimodal (Bi) multisensory, and Subthreshold (Sub) multisensory (see text for definitions). The number (and percent of sample) of neurons in these categories is shown according to the stimuli that influenced them.

| Uni A | Uni T | Bi AV | Bi AT | Sub AV | Sub AT | Sub AVT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 203 | 1 | 13 | 36 | 24 | 16 | 18 |

| Percent | 65.3 | 0.3 | 4.2 | 11.6 | 7.7 | 5.1 | 5.8 |

Tactile processing

The features of auditory responsivity of A1/AAF neurons have been extensively documented. In addition, several reports have dealt with the effects of visual stimulation in this region (Bizley et al., 2007; Bizley and King, 2009; Kayser et al., 2008). Like these studies, core auditory cortical neurons in the present investigation relatively few neurons exhibited overt, excitatory responses to visual stimulation (13/311; bimodal AV) while the responses to auditory stimulation were suppressed by an otherwise ineffective visual cue in many more units (42/311; Sub-AV, Sub-AVT). In contrast, little is known about single-unit processing of tactile stimulation within core auditory cortex. In the present study, many of the neurons influenced by tactile stimulation exhibited overt, excitatory responses to that modality (n=36/311, bimodal AT), such as depicted in Figure 3B. These tactile responses were most often generated by stimuli applied to the face, were usually activated by gentle air puffs (indicative of activation by low-threshold hair receptors), and failed to show a response to the sham-tactile trials. Moreover, the response evoked in these bimodal neurons by tactile stimulation was consistently far weaker than that elicited by an auditory cue in the same neurons. As demonstrated in Figure 5A (left panel), responses to tactile stimulation were about half as strong (average = 2.66 spikes/trial ± 0.26 s.e.) as auditory responses (average =4.94 spikes/trial ±0.57 s.e.) in the same group of neurons. Although it might be argued that the optimal tactile stimulus was not systematically sought, stimulus optimization was not attempted for the auditory cue either, and the tactile stimulation parameters used here have been shown to be highly effective in other preparations (Allman et al., 2009a; Foxworthy et al., 2013). For these bimodal neurons, a curious effect was observed when the auditory and tactile stimuli were combined. Instead of generating the summative or even facilitatory effect, Figure 5A (right panel) shows that the combined stimuli produced a response that was lower than that elicited by the auditory stimulus alone: suppression (average= 4.45 spikes/trial ± 0.49 s.e.; p<0.05, paired t-test). On the other hand, some neurons that failed to demonstrate an excitatory response to tactile stimulation revealed significant reductions of auditory activation when a tactile stimulus was co-presented. These neurons were subthreshold auditory-tactile neurons (n=34/311) and their response trends are displayed in Figure 5B, where tactile co-stimulation demonstrated a statistically significant (average = −14.5% ± 3.3 s.e.; p<0.0001; paired t-test) suppression of the auditory response. Perhaps most surprising, however, was the crossmodal effect on the population of unisensory auditory neurons. By definition, a unisensory neuron is activated by only one sensory modality and is not significantly influenced by the presentation (alone or in combination) of other sensory stimuli. However, in the present sample of unisensory auditory neurons (n=203), the average auditory response of the population (3.5 spikes/trial ± 0.2 s.e.) was subtly suppressed (average of −3.6% ± 1.2 s.e.) by the co-presentation of a tactile stimulus (average = 3.3 spikes/trial ± 0.2 s.e.) response and, as illustrated in Figure 5C, the line of best fit fell below the line of unity. Furthermore, a paired t-test found the subtle effect of tactile suppression of auditory responses in the population of unisensory auditory neurons to be statistically significant (p<0.013).

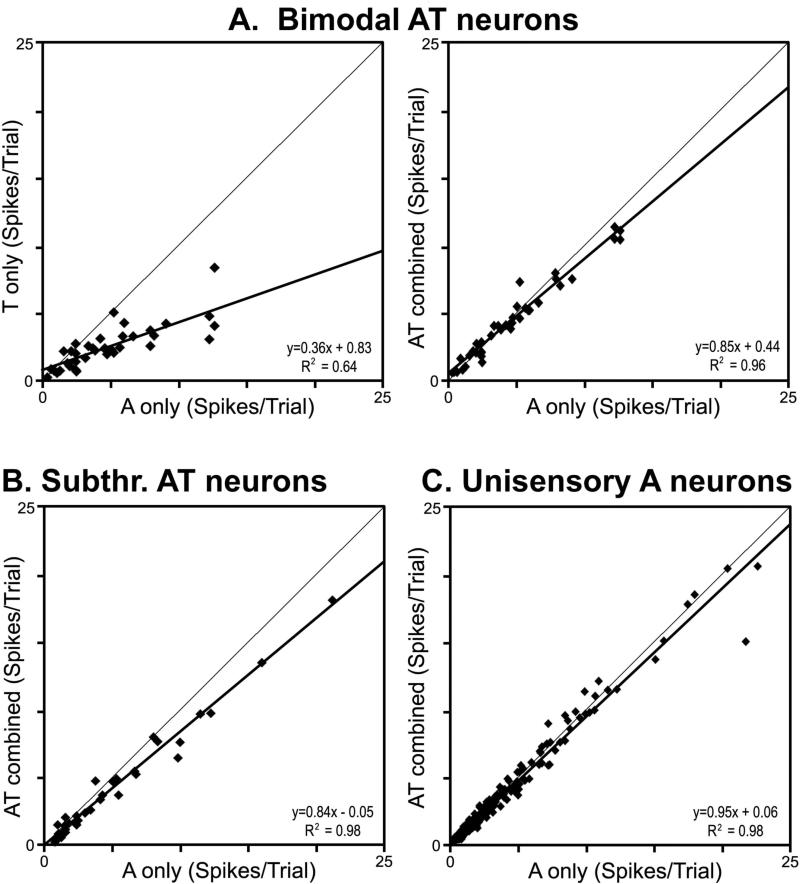

Figure 5.

Activity levels evoked in the different types of neurons encountered within core auditory cortex show a consistent effect of non-auditory stimulation. For neurons identified as bimodal (activated by auditory and by tactile cues), their responses to tactile cues was consistently far lower than that elicited by auditory stimulation (part A-left) and the combination of AT stimulation almost always resulted in a lower response than evoked by auditory stimulation alone (part A-right). Similarly, for neurons identified as subthreshold (activation by auditory cues modulated by tactile) showed that the combination of AT stimulation resulted in a lower response than evoked by auditory stimulation by itself (part B). The same cross-modal suppressive effect was even observed for the population of unisensory auditory neurons (part C), where combined AT stimulation produced a slight but significant depression in response when compared (for the same neuron) to auditory stimulation alone.

Tactile processing: Context

With the demonstrated presence of tactile effects in core auditory cortex, it is logical to try to understand these inputs affect the processing tasks of the region. One approach would be to evaluate the non-auditory effects in the context of the population activity of entire region. If it is assumed (with obvious caveats) that the sampled neurons are representative of the processing functions of core auditory cortex, a weighted relative measure of activity can be obtained by multiplying the sample response (average spikes/trial) by the number of neurons responsive to a given stimulus. For example, in the present study the proportion of core auditory cortex that was activated by acoustical cues was 310 (of 311; includes both unisensory and multisensory) neurons, which exhibited an average 4.17 spikes/trial to generate a population total of 1293 spikes (the product of 310 × 4.17), as summarized in Figure 6. By comparison, few neurons (n=55/311) were influenced by visual stimulation, and these responded to visual cues with an average 2.0 spikes/trial. Thus, for the entire sampled population, a visual stimulus elicited a hypothetical total of 110 spikes. Similarly, few neurons (n=71/311) were affected by tactile stimulation, averaging 2.34 spikes/stimulus that produced a total of 164 spikes. Both of these non-auditory population responses are plotted in Figure 6, where it is apparent that they are substantially lower than the auditory response total, and are even less than ongoing average spontaneous spiking level of the sample (dashed line). From these comparisons, it seems difficult to support the notion that non-auditory activity alone has substantial effects on auditory cortical processing and output. On the other hand, non-auditory stimulation has significant combined effects on auditory processing across all the types of auditory-responsive neurons. For the population of auditory-responsive neurons (n=310), the significant suppressive effects of visual (average = 3.90 spike/trial) and tactile (average = 3.96 spikes/trial) stimulation on auditory responsivity is depicted also in Figure 6. For each combination, the total spikes evoked from the sample population were significantly less than the activity generated by the auditory stimulus alone. These results indicate that the most pervasive and potent effects of non-auditory inputs to auditory cortex is that of suppression/modulation of auditory processing.

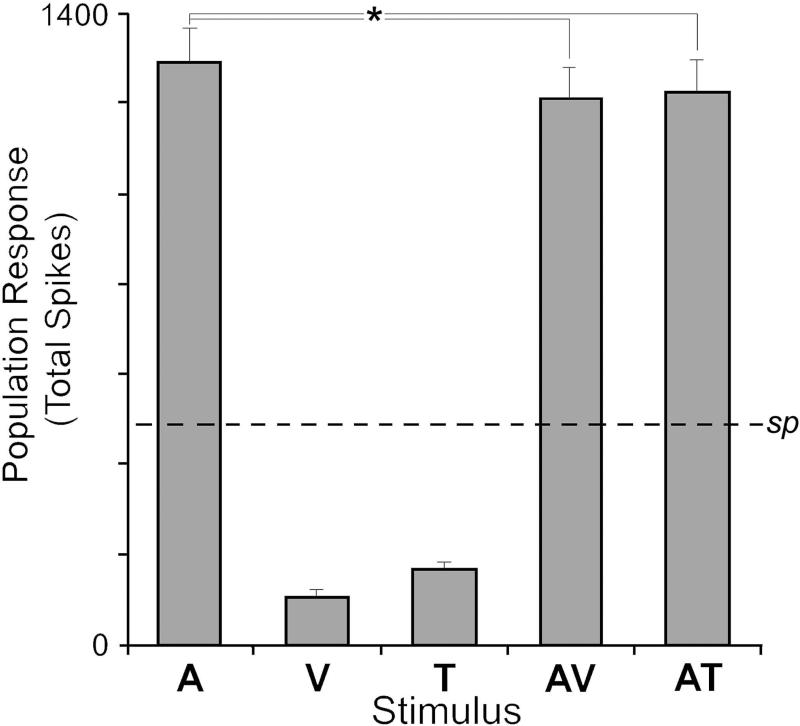

Figure 6.

Non-auditory effects on auditory cortex function are minimal when presented alone and are moderately suppressive when combined with auditory stimulation. Within the present sample, an auditory stimulus (A) elicited an average ~1300 spikes (± s.e.) from the population of activated neurons (sp=spontaneous level). When visual (V) or tactile (T) stimulation was presented alone, few neurons were activated and they responded with relatively few spikes. When combinations of auditory and non-auditory stimuli (AV, AT) were given, their responses averaged significantly (*, p<0.05) lower than auditory stimulation alone, but much higher than spontaneous levels or non-auditory stimulation alone. Hence, non-auditory stimuli largely modulate the output of core auditory cortex.

Somatosensory inputs: Sources

Given that somatosensory inputs are the most prevalent form of non-auditory effects in ferret core auditory cortex, it is important to identify the possible neural sources of these inputs. Toward that goal, tracer (BDA) injections were made into core auditory cortex of adult, male ferrets (n=4). Histochemical processing and light-microscopic reconstruction of the cortical hemisphere ipsilateral to the injection revealed the consistent presence of a large number of retrogradely labeled neurons. As illustrated for a representative case in Figure 7, retrogradely labeled neurons were largely identified within other auditory cortical areas. Few of the somatosensory regions outside S1 (Leclerc et al., 1993; Rice et al., 1993; McLaughlin et al., 1998) have been functionally mapped in the ferret, and few, if any labeled neurons were observed there or in the putative location for S2 (see Foxworthy and Meredith, 2011). However, one recently identified somatosensory region demonstrated robust and consistent bilaminar connectivity with core auditory cortices, as summarized in Figure 7D. This region is located in the lateral bank of the rostral suprasylvian sulcus (LRSS), between S1 on the medial side and portions of S2 and auditory cortex on the lateral side. The LRSS has been mapped (Keniston et al., 2008) and appears to contain a roughly somatotopic representation of the body representation which is in contrast to the primarily head/face representation found in the medial bank of the same sulcus (the MRSS; Keniston et al., 2009). The LRSS has been characterized to contain both tactile- (92%) and auditory-responsive (85%) neurons (numbers sum >100% due to numerous multisensory neurons; Keniston et al., 2008). Such a non-primary source of somatosensory cortical inputs to core auditory cortex is consistent with the non-primary nature of sources of auditory inputs to the visual cortex (see also Hall et al., 2008). Similarly, in the present study labeled neurons were not observed within primary visual areas (far posterior tissue sections contained no label and are not depicted), but inputs did arrive from the suprasylvian sulcal visual areas surrounding the auditory cortices such as the Anterolateral lateral suprasylvian (ALLS) and Posterolateral lateral suprasylvian (PLLS) areas (see Manger et al., 2008). It should be pointed out that the present injections into core auditory cortices heavily labeled the Medial geniculate nucleus, especially its lateral half, with a few retrogradely labeled neurons distributed within the Lateral-Posterior and Posterior thalamic nuclei; no labeled neurons were observed in Lateral geniculate or Ventral-basal nuclei. These patterns of thalamic connectivity confirm that the tracer injection sites were located within the core auditory cortices.

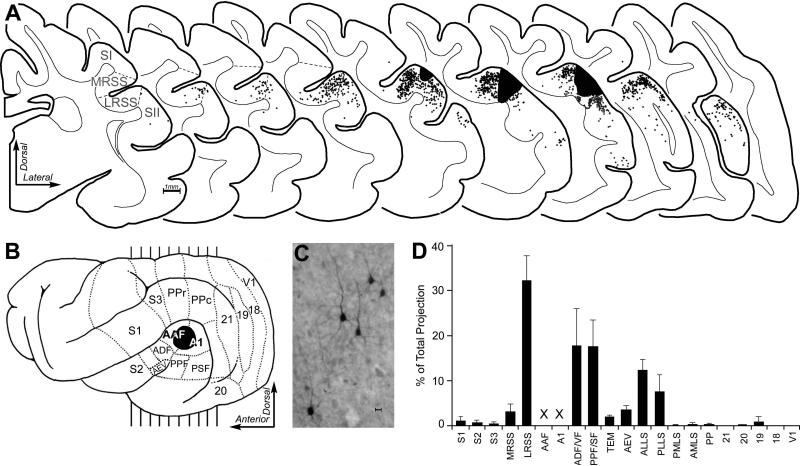

Fig 7.

Anatomical tracer injected into core auditory cortex produced retrogradely labeled neurons in multiple sections through ipsilateral cortex, as illustrated in part A. In part B, the lateral view of ferret cortex shows its functional subdivisions (borders indicated by dashed lines), the location of the BDA-tracer deposit (blackened area), and indications (vertical lines) of the anterior-posterior level from which the coronal sections in part A were derived. The coronal sections are serially arranged (anterior=left) and span the somatosensory and auditory cortices. Tracer injection (large black area) into A1/AAF retrogradely labeled neurons (each dot=1 labeled neuron), examples of which are depicted in the micrograph labeled “C” (scale bar = 10μm). Note that areas of somatosensory cortex (S1; S2) are largely devoid of label, although neurons projecting to A1/AAF were consistently observed within the somatosensory LRSS region. No labeled neurons were identified in sections anterior or posterior to those depicted. In part “D,” the bar graph summarizes (mean ± s.e.; n=4 cases) the proportion of retrogradely labeled neurons found in each cortical functional subdivision. Note the largest single cortical projection source to the core auditory regions is the LRSS. Labeled neurons within A1/AAF were not included (x x) in this analysis of extrinsic inputs to those regions.

Confirmation of the LRSS source of crossmodal inputs to core auditory cortex was derived from additional experiments that identified the termination pattern and location of boutons labeled from the LRSS. A representative case in which BDA tracer was injected into the LRSS is illustrated in Figure 8A. Using light microscopy, processed tissue sections through the middle ectosylvian gyrus revealed the presence of labeled axons and terminal boutons. These axons and terminals, as depicted in Figure 8, often were very fine in size which is typical of cortico-cortical connections. Histological reconstruction of the tissue sections and digital plots of the locations of labeled boutons consistently revealed the presence of axon terminals originating from LRSS within both A1 and AAF, as demonstrated in Figure 8, where the distribution of the terminal boutons was strongly biased toward the supragranular cortical layers. These patterns of LRSS projection termination within core auditory cortex were also observed in each of the other cases. Thus, the largely somatosensory projection to core auditory cortex has a bilaminar origin, with connected neurons located both in supragranular and infragranular layers of the LRSS (see Figure 5A sections 2-4). At its other end, LRSS projection terminates across the cortical mantle of A1/AAF, as illustrated in Figure 8B. When measured quantitatively, labeled LRSS boutons terminated primarily within the supragranular layers (layers 1-3; average=74.1% ± 0.2 s.e.), with proportionally fewer occurring in the granular (layer 4; 8.9% ± 3.8) and infragranular (layers 5-6; 16.9% ± 4.1) layers.

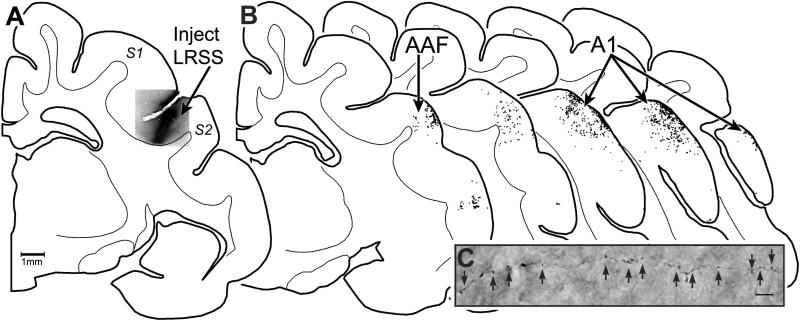

Figure 8.

LRSS projects to auditory areas A1/AAF. Part (A) shows a coronal section through the cortical hempisphere containing somatosensory areas S1 and S2, with the suprasylvian sulcus located between the two regions. Within the lateral bank of that sulcus is located the LRSS, which was injected with BDA tracer (photomicrograph, at arrow labeled LRSS). Part (B) shows serial coronal sections through the auditory cortices A1/AAF (at black arrows) with the locations of terminal boutons plotted (1 dot = 1 labeled bouton) confirming that LRSS projections terminate within both A1 and AAF. Part (C) shows representative example of labeled axons and boutons (at the black arrows) photomicrographed from within A1 (1000x, oil).

DISCUSSION

The present study examined the sensory activity of neurons recorded from the ferret middle ectosylvian gyrus corresponding to the areas A1 and AAF. In this species, tonotopic organization occurs essentially as horizontal bands that descend, with descending frequency, across the gyrus (Mrsic-Flogel et al, 2006). Only subtle response differences discriminate the two regions (described by Bizley et al., 2005) that require auditory testing parameters that were beyond the scope of the present investigation. Therefore, neurons from both areas were grouped and analyzed together as components of core (A1 and AAF) auditory cortex. Histological reconstruction of recording penetrations was used to exclude neurons potentially obtained from bordering sulcal areas that represent non-auditory functions, such as the visual areas ALLS, PLLS and AEV (Manger et al., 2005; 2008) and somatosensory area LRSS (Keniston et al., 2008). Within these constraints, the primary goal of this study was to examine the effect in core auditory cortex of non-auditory stimulation. The results demonstrate that neurons in core auditory cortex exhibit a pervasive, consistent, and subtle influence of visual and of somatosensory stimulation. Visual stimulation significantly affected ~17% of the identified neurons often in a suppressive manner, which is consistent with previous observations in this same species (Bizley et al., 2007). It should be noted that some excitatory responses to visual cues have been described when using LEDs as stimuli (Bizley et al., 2009), but much larger moving bars of light (which likely activated visual inhibitory surrounds) were employed in the present study. Not previously reported is the influence of tactile stimulation, which significantly affected ~23% of core auditory neurons.

Tactile reponses in auditory cortex

Within core auditory cortex, overt spiking responses to tactile stimulation occurred in 12% of the overall sample. These suprathreshold, spiking responses were substantially lower (in terms of spike number) than the acoustically-evoked responses of the same neurons: tactile responses averaged 2.7 spikes/trial, while the auditory response was almost twice that at an average 4.9 spikes/trial. Furthermore, suprathreshold tactile- or visual-evoked activity was so low and sparse that it fell nearly 4 times below the population level for spontaneous activity. It might be possible that the optimal tactile stimulus was not used, resulting in low response levels, especially for neurons in which excitatory responses to separate tactile stimulation were not evoked. Given the spatial distribution of the recording electrode (4 shank with 8 separate recording channels/shank), it was not possible to customize concurrent stimulation for each of the 32 recording sites. However, in studies where single-channel electrodes were used and individual receptive fields were mapped (Allman et al., 2009a), ~92% of neurons demonstrated somatosensory receptive fields on the face/head and, for that reason, the current study used tactile stimulation of the face as the default stimulation position. Collectively, the present data indicate that overt, suprathreshold tactile signaling is not likely to be a major contributor to core auditory cortical processing. Future studies in which a larger sample size is obtained could determine the laminar preferences of neurons with tactile responses, which could help assess the functional role for these uncommon effects. Another possibility is that non-auditory suprathreshold spiking was infrequently observed because the phenomenon is a consequence of network function that serves to suppress auditory-evoked activity (e.g., inhibitory interneurons). On the other hand, tactile stimulation most often reduced neuronal responses to concurrent auditory stimulation, and such suppression was even apparent on the overall population of unisensory auditory neurons. Similarly, visual co-stimulation of ferret auditory cortical neurons could generate suppressive effects (Bizley et al., 2007). It should be noted that crossmodal effects in hearing animals were sought but were only minimally observed (4% of sample) in another study of the ferret auditory cortex (Allman et al., 2009a), where lower impedance (<1MΩ) glass electrodes were used. However, when tactile suppression of auditory responses has been observed in the present study, the effect lowered acoustic responses by an average 7.1% across the entire sample of core auditory neurons. Thus, it is apparent that crossmodal effects in core auditory cortex are subtle, largely suppressive and pervasive.

Source of tactile inputs to auditory cortex

To identify the source of somatosensory inputs to core auditory cortex that could subserve crossmodal suppression, tracer injections were used to retrogradely label neurons that project to core auditory cortex. Of particular interest was the identification of labeled neurons in areas anterior and antero-dorsal to the auditory cortices where the somatosensory modality is represented. Although an atlas of the ferret brain does not yet exist, and comparatively few examinations of ferret somatosensory cortical representations are available, several publications have documented the location of primary somatosensory cortex (S1; Leclerc et al., 1993; Rice et al., 1993; McLaughlin et al., 1998). Within the cortical territory defined as S1, however, the present experiments identified very few neurons that were retrogradely labeled from the auditory cortices. Despite their presence, and the current pressure to identify primary-to-primary areal connections, it is obvious that these neurons occur in insufficient numbers to account for the pervasiveness of the somatosensory effect in auditory cortex. A similar quantitative issue exists in relation to auditory cortical projections that arise from S2, which is made even more problematic since the functional boundaries of this region in ferrets have not been published. Toward that end, a recent study that mapped the location of ferret S3 (Foxworthy and Meredith, 2011) used connectivity and other unpublished data to propose that S2 in this species is located on the anterior aspects of the anterior ectosylvian gyrus, which is a homologous location with the well-documented S2 region of the cat (Burton et al., 1982; Burton and Kopf, 1984). However, in either case, both ferret S1 and S2 exhibit far too few direct connections with auditory cortex to underlie the breadth of the tactile suppression of auditory responses. In contrast, a recently examined region between S1, S2 and auditory cortex, termed the Lateral rostral suprasylvian sulcus (LRSS; Keniston et al., 2008; 2009), revealed dense and consistent projections to the auditory cortices. This somatotopically organized region also exhibits sensory properties that are consistent with having a strong connection with auditory cortical areas, since the LRSS contains numerous (~65%) multisensory auditory-tactile neurons (Keniston et al., 2008). Ultimately, projections from LRSS terminate within and across both auditory fields of A1 and AAF. Thus, the LRSS demonstrates both a sufficient proportion of neurons that project to auditory cortex as well as terminated appropriately within the core auditory areas to subserve the observed crossmodal effects. It remains to be determined how the activity of the LRSS functions to suppress auditory responses in core auditory cortex.

Given the multisensory nature of the LRSS (Keniston et al., 2008), it might be expected that connections to lower-level, core auditory regions would exhibit a feedback-type organization (Felleman and Van Essen, 1991). Consistent with this notion is that neurons in the LRSS that project to A1/AAF exhibit a bilaminar arrangement as they reside in both supra- and infragranular layers. However, at the termination of the projection, LRSS axon terminals were observed across the cortical thickness and did not avoid layer 4, as would be expected for a feedback-type projection. Although this full-thickness distribution may more closely resemble the organization of a lateral-type projection, the LRSS terminations heavily favored the supragranular layers of A1/AAF, which is consistent with a host of other specifically crossmodal cortico-cortical projections (Dehner et al., 2004; Meredith et al., 2006; Clemo et al., 2007; 2008; Meredith and Clemo, 2010; Foxworthy et al., 2013).

At the cortical level, the pattern of somatosensory LRSS connectivity with auditory cortex suggests that higher order areas like the LRSS may serve as an indirect means of communication between lower level representations of different sensory modalities. The LRSS not only connects with core auditory cortex, but preliminary data also show that this somatosensory area has connections with nearby somatosensory areas S1 and S2. In addition, the present study identified neurons retrogradely labeled from auditory cortex in areas identified as visual representations ALLS, PLLS and AEV (Manger et al., 2008), but direct connections between primary auditory and primary visual regions were conspicuously absent. The notion of minimal direct primary-to-primary connections is also consistent with those demonstrated for ferret (Allman et al., 2009a) and cat cortex (Hall et al., 2008; Kok et al., 2014; Barone et al., 2013; Meredith et al., 2013) and the predominant trend in primate cortex (Falchier et al., 2003). Thus, such indirect cortical paths between primary sensory representations may represent an evolutionary adaptation to gyrification since lissencephalic rodent brains exhibit direct, primary-to-primary connectivity (Budinger et al., 2006). Ultimately, it should be recognized that such cortico-cortical connections may represent but one component of the crossmodal effects in core auditory cortex, since somatosensory inputs also converge upon and influence auditory activity within the Dorsal cochlear nucleus (Shore et al., 2000; 2003) and the Inferior colliculus (Aitken et al., 1981; Kanold and Young, 2001; Kanold et al., 2011) which are major brainstem relays within the ascending pathway to cortex.

Tactile inputs: functional role?

The present results indicate that while only a small proportion of auditory cortex is excited by tactile stimulation, an overwhelming proportion of neurons have their responses to acoustic stimuli modulated by the concurrent presence of tactile cues. Overall, tactile stimulation resulted in a 7.1% reduction in auditory-evoked activity. How these crossmodal influences affect spectral or temporal activity in auditory cortex remains to be determined and a specific, functional or perceptual role for crossmodal suppression in core auditory cortex likewise, remains to be empirically assessed. Several studies have used electrical nerve shocks to induce putative somatosensory-auditory interactions in auditory cortex, but it has not been confirmed whether these electrically induced inputs correlate with naturally timed tactile signals (Foxe et al., 2000; Basura et al., 2013). One possibility is that tactile inputs to auditory cortex could subtly modulate auditory perception possibly as a correlate with the “parchment-skin” illusion (Jousmaki and Hari, 1998; Guest et al., 2002), where filtered auditory cues have been demonstrated to influence tactile perception. Somatosensory convergence along the ascending auditory pathway may also provide clues to its possible function in cortex. For example, tactile inputs from the pinna region converge with auditory inputs in the inferior colliculus, where it has been postulated that information about pinna position and directionality could influence auditory spatial localization cues (Aitken et al., 1981; Kanold and Young, 2001; Kanold et al., 2011). Indeed, A1 cortex is often included as significant for auditory spatial localization (see for review: Malhotra and Lomber, 2007) and it is conceivable that modulation by tactile inputs could contribute to this function. Perhaps most striking is that somatosensory convergence with auditory signals occurs at the very first node in the ascending auditory pathway, the cochlear nucleus, as demonstrated by a large number of mutually-confirmatory studies (Shore et al., 2000; 2003; Basura et al., 2012; Zeng et al., 2012). The logical implication of this phenomenon is that upstream stations may be affected, including cortex, whereby suppression of perception of self-induced sounds may occur.

Tactile unmasking and hearing loss

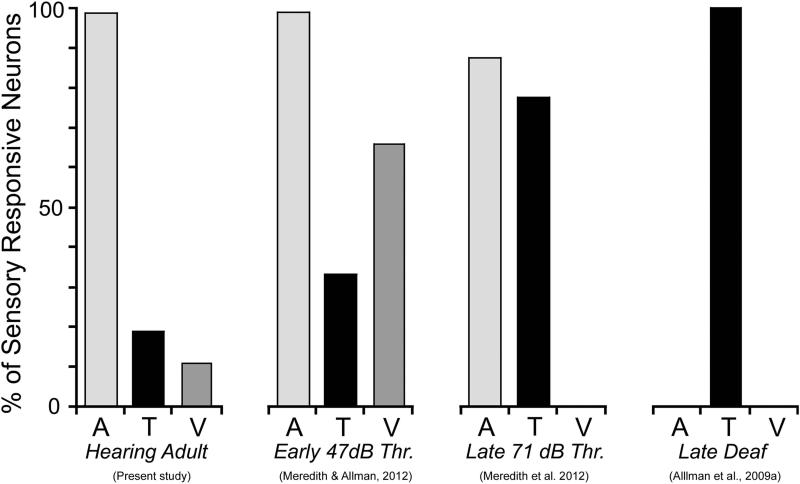

The present study provides an important insight into the ongoing debate regarding the mechanisms of crossmodal plasticity, which is the replacement of lost sensory input (i.e., deafness) with activity from the remaining, intact sensory systems. Numerous authors have speculated that crossmodal plasticity results from either (or the combination of) the ingrowth of new connections from non-auditory sources, or the unmasking/reweighting of existing non-auditory inputs (e.g., Rauschecker, 1995; Bavalier and Neville, 2002). A spate of recent connectional studies of deafened ferrets (Allman et al., 2009a; Meredith and Allman, 2012) and cats (Kok et al., 2013; Barone et al., 2013) indicate that few, if any, new neural connections arise as a consequence of deafness. Alternatively, recent studies of hearing auditory cortex (Foxe et al., 2000; 2002; Bizley et al., 2007; Bizley and King, 2009; Kayser et al., 2008; Basura et al., 2013; present investigation) indicate that the presence of non-auditory (visual, somatosensory) inputs to core auditory cortex could provide the connectional and functional substrate for the crossmodal plasticity that follows the loss auditory inputs. In fact, the correspondence is remarkable. Somatosensory inputs to core auditory cortex represent the majority of non-auditory effects in hearing ferrets (present study), and crossmodal somatosensory effects dominate the auditory cortical responses of early-hearing impaired (Meredith and Allman, 2012), late-deaf (Allman et al., 2009a) and late-hearing impaired (Meredith et al. 2012) ferrets. For these different conditions, the relative contribution of somatosensory influences on auditory cortex is compared in Figure 9. Collectively, these studies show that subtle, subthreshold tactile effects evident across the population of auditory cortical neurons in hearing animals transform in deaf animals into overt, suprathreshold responses driven largely by hair receptors exhibiting standard somatosensory receptive field properties. Somatosensory crossmodal effects following deafness have also been demonstrated for the AAF and FAES of cats (Meredith and Lomber, 2011; Meredith et al., 2011) and auditory cortex of rodents (Hunt et al., 2006) and humans (Auer et al., 2005; Karns et al., 2012). Therefore, the unmasking and reweighting of existing connections in hearing animals appears to provide a substrate for crossmodal plasticity observed following deafness.

Figure 9.

A summary of the presence of non-auditory effects in core auditory cortex from normal hearing (left – present study) and for several published studies following hearing loss where hearing threshold (Thr.) averaged 47dB SPL (early-hearing impaired; Meredith & Allman, 2012), 71 dB SPL (late-deaf; Meredith et al., 2013) or showed profound (>90dB SPL; late deaf; Allman et al., 2009a) hearing loss. These results indicate that the proportion of crossmodal effects increases with increasing levels of hearing loss. A=auditory; T=tactile; V=visual.

To date, the major criticism of the involvement of somatosensation in cortical crossmodal plasticity is that it is unexpected. Indeed, much of the literature dealing with deafness-induced cortical crossmodal effects is based on visual effects (e.g., Rauschecker, 1995; Bavalier and Neville, 2001) or lack there-of (Kral et al., 2003). These visually-biased expectations are of obvious heuristic value, since there are undisputable links between vision and spatial hearing (e.g., Knudsen and Knudsen, 1985) as well as between vision and language perception in both hearing and deaf individuals (e.g., Cardin et al., 2013). Nevertheless, many of the studies documenting visual participation in crossmodal plasticity did so to the exclusion of somatosensation. Furthermore, the different auditory cortices are known to react differently following deafness (Lomber et al., 2010) and the “supramodal hypothesis” for crossmodal plasticity predicts that the features and function of crossmodal plasticity are expressed on a region-by-region basis. Given that significant species-based differences also occur within the auditory system (e.g., the orientation of isofrequency bands in A1/AAF), the collective influences of these different variables suggest that crossmodal plasticity is far from a unidimensional effect and is one in which somatosensation can play a significant role.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank L. Keniston for programming and data collection assistance, and H.R. Clemo for comments on the manuscript. Supported by NIH Grant NS39460 and VCU PRIP (MAM) and NSERC Discovery grant (BLA).

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

- A1

Primary Auditory Cortex

- AAF

Anterior Auditory Field

- ADF

Antero-Dorsal (auditory) Field

- AEV

Ectosylvian Visual Area

- ALLS

Antero-Lateral Lateral Suprasylvian (visual) Cortex

- AMLS

Antero-Medial Lateral Suprasylvian (visual) Cortex

- Areas 18,19, 20, 21

Numbered visual cortical áreas

- AVF

Antero-Ventral (auditory) Field

- LG

Lateral Geniculate thalamic nucleus

- LP

Lateral Posterior thalamic nucleus

- LRSS

Lateral Rostral Suprasylvian Sulcus (somatosensory)

- MG

Medial geniculate thalamic nucleus

- MRSS

Medial Rostral Suprasylvian Sulcus (somatosensory)

- PLLS

Posterolateral Lateral Suprasylvian (visual) Cortex

- PMLS

Posteromedial Lateral Suprasylvian (visual) Cortex

- PO

Posterior thalamic nucleus

- PPc

Posterior Parietal Cortex, c=caudal

- PPF

Posterior Pseudosylivan (auditory) Field

- PPr

Posterior Parietal Cortex, r=rostral

- PSF

Posterior Suprasylvian (auditory) Field

- S1

Primary Somatosensory Cortex

- S2

Secondary Somatosensory Cortex

- S3

Third Somatosensory Cortex

- TEM

Temporal (auditory) Field

- V1

Primary Visual Cortex

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST:

The authors declare no conflicts of interest related to this work.

REFERENCES

- Aitkin LM, Kenyon CE, Philpott P. The representation of the auditory and somatosensory systems in the external nucleus of the cat inferior colliculus. J. Comp. Neurol. 1981;196:25–40. doi: 10.1002/cne.901960104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allman BL, Bittencourt-Navarrete RE, Keniston LP, Medina A, Wang MY, Meredith MA. Do cross-modal projections always result in multisensory integration? Cereb. Cortex. 2008;18:2066–2076. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allman BL, Keniston LP, Meredith MA. Adult-deafness induces somatosensory conversion of ferret auditory cortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009a;106:5925–5930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809483106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allman BL, Keniston LP, Meredith MA. Not just for bimodal neurons anymore: The contribution of unimodal neurons to cortical multisensory processing. Brain Topogr. 2009b;21:157–167. doi: 10.1007/s10548-009-0088-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auer ET, Jr., Bernstein LE, Sungkarat W, Singh M. Vibrotactile activation of the auditory cortices in deaf versus hearing adults. Neuroreport. 2007;18:645–648. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3280d943b9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barone P, Lacassagne L, Kral A. Reorganization of the connectivity of cortical field DZ in congenitally deaf cat. PLoS One. 2013;8:e0060093. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basura GJ, Koehler SD, Shore SE. Multi-sensory integration in brainstem and auditory cortex. Brain Res. 2012;1485:95–107. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bavelier D, Dye MW, Hauser PC. Do deaf individuals see better? Trends Cogn. Sci. 2006;10:512–518. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bavelier D, Neville HJ. Cross-modal plasticity: where and how? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2002;3:443–452. doi: 10.1038/nrn848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell AH, Corneil BD, Meredith MA, Munoz DP. The influence of stimulus properties on multisensory processing in the awake primate superior colliculus. Can. J. Exp. Psychol. 2001;55:125–134. doi: 10.1037/h0087359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bizley JK, Nodal FR, Nelken I, King AJ. Functional organization of ferret auditory cortex. Cereb. Cortex. 2005;15:1637–1653. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhi042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bizley JK, Nodal FR, Bajo VM, Nelken I, King AJ. Physiological and anatomical evidence for multisensory interactions in auditory cortex. Cereb. Cortex. 2007;17:2172–2189. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhl128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bizley JK, King AJ. Visual influences on ferret auditory cortex. Hear. Res. 2009;258:55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2009.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budinger E, Heil P, Hess A, Scheich H. Multisensory processing via early cortical stages: Connections of the primary auditory cortical field with other sensory systems. Neurosci. 2006;143:1065–1083. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton H, Kopf EM. Ipsilateral cortical connections from the second and fourth somatic sensory areas in the cat. J. Comp. Neurol. 1984;225:527–53. doi: 10.1002/cne.902250405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton H, Mitchell G, Brent D. Second somatic sensory area in the cerebral cortex of cats: somatotopic organization and cytoarchitecture. J. Comp. Neurol. 1982;210:109–35. doi: 10.1002/cne.902100203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardin V, Orfanidou E, Ronnberg J, Capek CM, Rudner M, Woll B. Dissociating cognitive and sensory neural plasticity in human superior temporal cortex. Nat. Comm. 2013;4:1473. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemo HR, Allman BL, Donlan AM, Meredith MA. Sensory and Multisensory Representations within the Cat Rostral Suprasylvian Cortex. J. Comp. Neurol. 2007;503:110–127. doi: 10.1002/cne.21378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemo HR, Lomber SG, Meredith MA. Synaptic Basis for Crossmodal Plasticity: Enhanced Supragranular Dendritic Spine Density in Anterior Ectosylvian Auditory Cortex of the Early-Deaf Cat. Cereb. Cortex. 2014:bhu225. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhu225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemo HR, Sharma GK, Allman BL, Meredith MA. Auditory projections to extrastriate visual cortex: connectional basis for multisensory processing in ‘unimodal’ visual neurons. Exp. Brain Res. 2008;191:37–47. doi: 10.1007/s00221-008-1493-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehner LR, Keniston LP, Clemo HR, Meredith MA. Cross-modal Circuitry Between Auditory and Somatosensory Areas of the Cat Anterior Ectosylvian Sulcal Cortex: A ‘New’ Inhibitory Form of Multisensory Convergence. Cereb. Cortex. 2004;14:387–403. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhg135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falchier A, Clavagnier S, Barone P, Kennedy H. Anatomical evidence of multimodal integration in primate striate cortex. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:5749–59. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-13-05749.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felleman DJ, Van Essen DC. Distributed hierarchical processing in the primate cerebral cortex. Cereb. Cortex. 1991;1:1–47. doi: 10.1093/cercor/1.1.1-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finney EM, Fine I, Dobkins KR. Visual stimuli activate auditory cortex in the deaf. Nat. Neurosci. 2001;4:1171–3. doi: 10.1038/nn763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foxe JJ, Morocz IA, Murray MM, Higgins BA, Javitt DC, Schroeder CE. Multisensory auditory-somatosensory interactions in early cortical processing revealed by high-density electrical mapping. Brain Res. Cogn. Brain Res. 2000;10:77–83. doi: 10.1016/s0926-6410(00)00024-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foxe JJ, Wylie GR, Martinez A, Schroeder CE, Javitt DC, Guilfoyle D, Ritter W, Murray MM. Auditory-somatosensory multisensory processing in auditory association cortex: an fMRI study. J. Neurophysiol. 2002;88:540–3. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.88.1.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foxworthy WA, Clemo HR, Meredith MA. Laminar and connectional organization of a multisensory cortex. J. Comp. Neurol. 2013;521:1867–90. doi: 10.1002/cne.23264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foxworthy WA, Meredith MA. An examination of somatosensory area SIII in ferret cortex. Somat. & Mot. Res. 2011;28:1–10. doi: 10.3109/08990220.2010.548465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghazanfar AA, Maier JX, Hoffman KL, Logothetis NK. Multisensory integration of dynamic faces and voices in rhesus monkey auditory cortex. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:5004–5012. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0799-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guest S, Catmur C, Lloyd D, Spence C. Audiotactile interactions in roughness perception. Exp. Brain Res. 2002;146:161–71. doi: 10.1007/s00221-002-1164-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall AJ, Lomber SG. Auditory cortex projections target the peripheral field representation of primary visual cortex. Exp. Brain Res. 2008;190:413–30. doi: 10.1007/s00221-008-1485-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoefer M, Tyll S, Kanowski M, Brosch M, Schoenfeld MA, Heinze HJ, Noesselt T. Tactile stimulation and hemispheric asymmetries modulate auditory perception and neural responses in primary auditory cortex. NeuroImage. 2013;79:371–382. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.04.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt DL, Yamoah EN, Krubitzer L. Multisensory plasticity in congenitally deaf mice: how are cortical areas functionally specified? Neurosci. 2006;139:1507–1524. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jousmaki V, Hari R. Parchment-skin illusion: sound-biased touch. Curr .Biol. 1998;8:R190. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70120-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanold PO, Young ED. Proprioceptive information from the pinna provides somatosensory input to cat dorsal cochlear nucleus. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:7848–7858. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-19-07848.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanold PO, Davis KA, Young ED. Somatosensory context alters auditory responses in the cochlear nucleus. J. Neurophysiol. 2011;105:1063–70. doi: 10.1152/jn.00807.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karns CM, Dow MW, Neville HJ. Altered cross-modal processing in the primary auditory cortex of congenitally deaf adults: a visual-somatosensory fMRI study with a double-flash illusion. J. Neurosci. 2012;32:9626–38. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6488-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayser C, Logothetis NK. Do early sensory cortices integrate cross-modal information? Brain Struct. Funct. 2007;212:121–132. doi: 10.1007/s00429-007-0154-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayser C1, Petkov CI, Augath M, Logothetis NK. Integration of touch and sound in auditory cortex. Neuron. 2005;48:373–84. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayser C, Petkov CI, Logothetis NK. Visual modulation of neurons in auditory cortex. Cereb. Cortex. 2008;18:1560–1574. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayser C1, Petkov CI, Logothetis NK. Multisensory interactions in primate auditory cortex: fMRI and electrophysiology. Hear. Res. 2009;258:80–8. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keniston LP, Allman BL, Meredith MA. Multisensory character of the lateral bank of the rostral suprasylvian sulcus in ferret. Soc. Neurosci. Abstr. 2008;38:457.10. [Google Scholar]

- Keniston LP, Allman BA, Meredith MA, Clemo HR. Somatosensory and multisensory properties of the medial bank of the ferret rostral suprasylvian sulcus. Exp. Brain Res. 2009;196:239–251. doi: 10.1007/s00221-009-1843-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen EI, Knudsen PF. Vision guides the adjustment of auditory localization in young barn owls. Science. 1985;230:545–8. doi: 10.1126/science.4048948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kok MA, Chabot N, Lomber SG. Cross-modal reorganization of cortical afferents to dorsal auditory cortex following early- and late-onset deafness. J. Comp. Neurol. 2014;522:654–75. doi: 10.1002/cne.23439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kral A, Schröder JH, Klinke R, Engel AK. Absence of cross-modal reorganization in the primary auditory cortex of congenitally deaf cats. Exp. Brain Res. 2003;153:605–13. doi: 10.1007/s00221-003-1609-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leclerc SS, Rice FL, Dykes RW, Pourmoghadam K, Gomez CM. Electrophysiological examination of the representation of the face in the suprasylvian gyrus of the ferret: A correlative study with cytoarchitecture. Somat. & Mot. Res. 1993;10:133–159. doi: 10.3109/08990229309028829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomber SG, Meredith MA, Kral A. Crossmodal plasticity in specific auditory cortices underlies visual compensations in the deaf. Nat. Neurosci. 2010;13:1421–1427. doi: 10.1038/nn.2653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra S, Lomber SG. Sound localization during homotopic and heterotopic bilateral cooling deactivation of primary and nonprimary auditory cortical areas in the cat. J. Neurophysiol. 2007;97:26–43. doi: 10.1152/jn.00720.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manger PR, Engler G, Moll CK, Engel AK. The anterior ectosylvian visual area of the ferret: a homologue for an enigmatic visual cortical area of the cat? Eur. J. Neurosci. 2005;22:706–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manger PR, Engler G, Moll CK, Engel AK. Location, architecture, and retinotopy of the anteromedial lateral suprasylvian visual area (AMLS) of the ferret (Mustela putorius). Vis. Neurosci. 2008;25:27–37. doi: 10.1017/S0952523808080036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manger PR, Kiper D, Masiello I, Murillo L, Tettoni L, Hunyadi Z, Innocenti GM. The representation of the visual field in three extrastriate areas of the ferret (Mustela putorius) and the relationship of retinotopy and field boundaries to callosal connectivity. Cereb. Cortex. 2002a;12:423–37. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.4.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manger PR, Masiello I, Innocenti GM. Areal organization of the posterior parietal cortex of the ferret (Mustela putorius). Cereb. Cortex. 2002b;12:1280–97. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.12.1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin DF, Sonty RV, Juliano SL. Organization of the forepaw representation in ferret somatosensory cortex. Somat. & Mot. Res. 1998;15:253–68. doi: 10.1080/08990229870673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith MA, Allman BL. Early hearing-impairment results in crossmodal reorganization of ferret core auditory cortex. Neural Plast. 2012;2012:601591. doi: 10.1155/2012/601591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith MA, Clemo HR. Corticocortical connectivity subserving different forms of multisensory convergence. In: Naumer MJ, Kaiser J, editors. Multisensory Object Perception in the Primate Brain. Springer; NY: 2010. pp. 7–20. [Google Scholar]

- Meredith MA, Keniston LP, Allman BL. Multisensory dysfunction accompanies crossmodal plasticity following adult hearing impairment. Neurosci. 2012;214:136–148. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith MA, Keniston LP, Dehner LR, Clemo HR. Crossmodal projections from somatosensory area SIV to the auditory field of the anterior ectosylvian sulcus (FAES) in cat: further evidence for subthreshold forms of multisensory processing. Exp. Brain Res. 2006;172:472–484. doi: 10.1007/s00221-006-0356-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith MA, Kryklywy J, McMillan AJ, Malhotra S, Lum-Tai R, Lomber SG. Crossmodal Reorganization in the Early-Deaf Switches Sensory, but not Behavioral Roles of Auditory Cortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:8856–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018519108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith MA, Lomber SG. Somatosensory and visual crossmodal plasticity in the anterior auditory field of early-deaf cats. Hear. Res. 2011;280:38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrsic-Flogel TD, Versnel H, King AJ. Development of contralateral and ipsilateral frequency representations in ferret primary auditory cortex. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2006;23:780–792. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordmark PF, Pruszynski JA, Johansson RS. BOLD responses to tactile stimuli in visual and auditory cortex depend on the frequency content of stimulation. J. Cognit. Neurosci. 2012;24:2120–2134. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay AM, Meredith MA. Multiple sensory afferents to ferret pseudosylvian sulcal cortex. Neuroreport. 2004;15:461–465. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200403010-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauschecker JP. Compensatory plasticity and sensory substitution in the cerebral cortex. Trends Neurosci. 1995;18:36–43. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)93948-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice FL, Gomez CM, Leclerc SS, Dykes RW, Moon JS, Pourmoghadam K. Cytoarchitecture of the ferret suprasylvian gyrus correlated with areas containing multiunit responses elicited by stimulation of the face. Somat. & Mot. Res. 1993;10:161–188. doi: 10.3109/08990229309028830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shore SE, El Kashlan H, Lu J. Effects of trigeminal ganglion stimulation on unit activity of ventral cochlear nucleus neurons. Neurosci. 2003;119:1085–101. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00207-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shore SE, Vass Z, Wys NL, Altschuler RA. Trigeminal ganglion innervates the auditory brainstem. J. Comp. Neurol. 2000;419:271–85. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(20000410)419:3<271::aid-cne1>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schurmann M, Caetano G, Hlushchuk Y, Jousmaki V, Hari R. Touch activates human auditory cortex. NeuroImage. 2006;30:1325–1331. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veenman CL, Reiner A, Honig MG. Biotinylated dextran amine as an anterograde tracer for single- and double-labeling studies. J. Neurosci. Methods. 1992;41:239–54. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(92)90089-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng C, Yang Z, Shreve L, Bledsoe S, Shore S. Somatosensory projections to cochlear nucleus are upregulated after unilateral deafness. J. Neurosci. 2012;32:15791–801. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2598-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]