Abstract

Objective

To describe recent maternal and neonatal delivery outcomes among women with a morbidly adherent placenta in major centers across the United States.

Methods

This study reviewed a cohort of 115,502 women and their neonates born in 25 hospitals in the United States between March 2008 and February 2011 from the Assessment of Perinatal EXcellence data set. All cases of morbidly adherent placenta were identified. Maternal demographics, procedures undertaken and maternal and neonatal outcomes were analyzed.

Results

There were 158 women with a morbidly adherent placenta (1 per 731 births [95%CI: 1 per 632, 1 per 866]). Eighteen percent of women with a morbidly adherent placenta were nulliparous and 37% had no prior cesarean delivery. Only 53% (84/158) were suspected to have a morbidly adherent placenta before delivery. Women with a prenatally suspected morbidly adherent placenta experienced large blood loss (33%), hysterectomy (92%) and intensive care unit admission (39%) compared with 19%, 45% and 22%, respectively, in those not suspected to have a morbidly adherent placenta(p<.05 for all).

Conclusion

Eighteen percent of women with a morbidly adherent placenta were nulliparous. Half of the morbidly adherent placenta cases were suspected before delivery and outcomes were poorer in this group, probably because the more clinically significant morbidly adherent placentas are more likely to be suspected before delivery.

INTRODUCTION

The incidence of morbidly adherent placenta has increased, with recent estimates approximating 1 per 333 – 1 per 533 deliveries. 1, 2 Transfer of women with suspected placenta accretas to major centers for delivery has been recommended to assure access to large blood banks, prompt availability of subspecialty surgeons, and experienced intensive care units.1, 3 Optimal care for women with morbidly adherent placenta should be based on recent information that allows women and their caregivers to prepare for the complications that may accompany delivery. Studies to date typically described a relatively small number of patients from one or two centers often including patients cared for over a decade or more. 2, 4, 5 Previous studies from the MFMU on this topic were restricted to women having a cesarean delivery. 6 Perinatal outcomes have not been reported for large numbers of women whose pregnancies were complicated by placenta accreta in recent years.

The Assessment of Perinatal EXcellence study was an observational study that concurrently collected information on women between 2008 and 2011 at 25 hospitals around the United States.7 These data offer the opportunity to examine a contemporary population of women with morbidly adherent placenta. Thus, we sought to examine a sub-population of women with morbidly adherent placenta from the Assessment of Perinatal EXcellence cohort and describe the characteristics of these women and their babies and quantify the frequency of maternal and perinatal delivery outcomes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Between 2008 and 2011, we assembled a cohort of women and their neonates born in any of 25 hospitals in the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units (MFMU) Network. The Assessment of Perinatal EXcellence study was designed to develop quality measures for intrapartum obstetric care. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at each participating institution under a waiver of informed consent. This article presents a secondary analysis of the Assessment of Perinatal EXcellence data.

Full details of data collection have been described previously.7 Briefly, any patient who delivered at one of the participating institutions, was at least 23 weeks gestational age, and had a live fetus on admission was included. Data were collected on randomly selected days occurring over a three-year period (March 2008 to February 2011). Days were chosen through computer-generated random selection and balanced for weekends and holidays. To avoid overrepresentation of patients from larger hospitals, we selected one-third of days at hospitals with annual delivery volumes from 2,000 to 7,000 and up to one-sixth of days at hospitals with annual deliveries > 7,000. The randomization scheme was generated separately for each hospital. The medical records for all eligible women and babies were abstracted by trained and certified research personnel and entered into a web-based data entry system. Medical records included hospitalization records as well as any prenatal records available at the time of delivery. Data recorded included demographic characteristics, details of the medical and obstetric history, and information about intrapartum and postpartum events, including maternal and neonatal outcomes. Maternal data were collected until discharge and neonatal data were collected up until discharge or until 120 days of age, whichever came first. Most of the 25 hospitals were tertiary care centers.

The diagnosis of morbidly adherent placenta was based on the medical records available at the time of the delivery hospitalization. Morbidly adherent placenta was considered present if the placenta was adherent to the uterine wall without easy separation at or immediately after delivery. Increta was present if the placenta was invading the uterine muscle and percreta was present if the placenta was invading through to the uterine serosa. All of the remaining cases were considered accretas. For the present analysis, all women meeting any of these definitions of morbidly adherent placenta, regardless of mode of delivery or treatments given, were classified as morbidly adherent placenta. Pathology reports were not required. All cases considered accreta, increta or percreta were double checked by re-reviewing the medical records at a later date from the initial collection and the diagnosis was re-confirmed from medical records. Furthermore, data were collected to ascertain whether or not the morbidly adherent placenta was suspected prior to delivery (any time in the pregnancy prior to delivery) as documented in the chart.

Descriptive analyses were used to report the frequency of maternal and neonatal adverse outcomes. Maternal outcomes included: maternal ICU stay during the delivery hospitalization, clinically determined estimated blood loss (EBL), number of units of packed red cells transfused, units of fresh frozen plasma transfused, units of cryoprecipitate transfused, units of platelets transfused, significant hypotension (defined as systolic blood pressure <80 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure of <50 mm Hg on at least two occasions at least 30 minutes apart), significant tachycardia (defined as maternal pulse >120 beats per minute at any time for any duration after delivery), maternal ventilatory support, any unanticipated additional maternal surgical procedures (including repair of other organs and hysterectomy), and length of stay. Neonatal outcomes recorded included gestational age at delivery, need for ventilatory support within 24 hours of birth, size for gestational age (small [<10th percentile], appropriate, large [>90th percentile]) per methods of Duryea et al, 8 and length of neonatal stay. Because we only had data through the delivery hospitalization, complications or surgeries that occurred after delivery hospitalization discharge were not obtained.

The frequencies of adverse outcomes were compared between women whose morbidly adherent placenta was suspected prior to delivery and women whose morbidly adherent placenta was diagnosed at delivery. Outcomes were also compared based on the different therapeutic interventions (i.e., hysterectomy, uterine artery ligation, hypogastric artery ligation, B-Lynch suture, balloon tamponade) as well as whether the delivery was scheduled or not. Analyses used chi square or Fisher's exact where appropriate for categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank-sum for continuous variables. No imputation for missing data was performed. All tests were two-tailed, p<.05 was used to define statistical significance, there was no adjustment for multiple comparisons, and analyses were performed using SAS software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

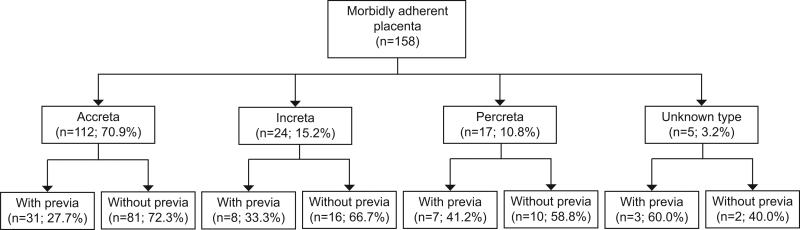

Data were collected from 115,502 women. The 25 hospitals in which women were enrolled are mostly teaching institutions (22/25, 88%) and had a median annual number of deliveries captured in the Assessment of Perinatal EXcellence study of 4252 (range 1754 to 9262). There were 158 morbidly adherent placentas in the population, for an overall frequency of 1 per 731 births (95% CI: 1 per 632, 1 per 866), although the frequency among hospitals varied significantly from none to 1 per 197 births (P<.001). When applying weights, to account for our sampling scheme in which larger hospitals had fewer days selected and assuming a standardized 365 selected days at each hospital, the frequency of morbidly adherent placenta was 1 per 756 births (95% CI: 1 per 654,1 per 897). Figure 1 provides the frequency of each type of morbidly adherent placenta and whether or not it occurred with previa.

Figure 1.

Frequency of each type of morbidly adherent placenta and whether or not it occurred with previa.

Many of the women with a diagnosis of morbidly adherent placenta were older than 35 years (36.7%), non-Hispanic white (50.6%) and had private insurance (59.0%) (Table 1). Many women did not have traditional risk factors, with 18.4% being nulliparous and 37.3% having no prior cesarean delivery. Of note, 10.1% had a prior cesarean delivery with a classical, T or J incision.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the morbidly adherent placenta patients (n=158)

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, years | |

| < 30 | 53 (33.5) |

| 30-34.9 | 47 (29.8) |

| ≥ 35 | 58 (36.7) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 80 (50.6) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 28 (17.7) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 7 (4.4) |

| Hispanic | 29 (18.4) |

| Other | 9 (5.7) |

| Not Documented | 5 (3.2) |

| Cigarette use during pregnancy | 18 (11.4) |

| Cocaine or methamphetamine use during pregnancy | 3 (1.9) |

| Insurance status | |

| Uninsured/self-pay | 11 (7.1) |

| Government-assisted | 53 (34.0) |

| Private | 92 (59.0) |

| Number of prior pregnancies ≥ 20 weeks | |

| 0 (nulliparous) | 29 (18.4) |

| 1 | 40 (25.3) |

| 2 | 45 (28.5) |

| 3+ | 44 (27.9) |

| Number of prior cesareans | |

| 0 | 59 (37.3) |

| 1 | 37 (23.4) |

| 2 | 34 (21.5) |

| 3+ | 28 (17.7) |

| Prior classical, T or J uterine incision | 16 (10.1) |

| Steroids for fetal lung maturity | 61 (38.6) |

| Amniocentesis for lung maturity | 9 (5.7) |

| Placenta previa | 49 (31.0) |

| Number of prior cesareans among those with placenta previa (n=49) | |

| 0 | 11 (22.5) |

| 1 | 15 (30.6) |

| 2 | 9 (18.4) |

| 3+ | 14 (28.6) |

| Number of prior cesareans among those without placenta previa (n=109) | |

| 0 | 48 (44.0) |

| 1 | 22 (20.2) |

| 2 | 25 (22.9) |

| 3+ | 14 (12.8) |

| Number of women with previa among nulliparous women with suspected morbidly adherent placenta (n=3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Number of women with previa among nulliparous women without suspected morbidly adherent placenta (n=26) | 4 (15.4) |

| Number of prior pregnancies < 20 weeks in nulliparous women among those with placenta previa (n=4) | |

| 0 | 4 (100.0) |

| 1 | 0 (0.0) |

| 2 | 0 (0.0) |

| Number of prior pregnancies < 20 weeks in nulliparous women among those without placenta previa (n=25) | |

| 0 | 12 (48.0) |

| 1 | 10 (40.0) |

| 2 | 3 (12.0) |

| Prior classical, T or J uterine incision among those with placenta previa (n=49) | 6 (12.2) |

| Prior classical, T or J uterine incision among those without placenta previa (n=109) | 10 (9.2) |

| Number of prior cesareans among those with suspected morbidly adherent placenta (n=84) | |

| 0 | 11 (13.1) |

| 1 | 24 (28.6) |

| 2 | 26 (31.0) |

| 3+ | 23 (27.4) |

| Number of prior cesareans among those without suspected morbidly adherent placenta (n=74) | |

| 0 | 48 (64.9) |

| 1 | 13 (17.6) |

| 2 | 8 (10.8) |

| 3+ | 5 (6.8) |

| Prior classical, T or J uterine incision among those with suspected morbidly adherent placenta (n=84) | 14 (16.7) |

| Prior classical, T or J uterine incision among those without suspected morbidly adherent placenta (n=74) | 2 (2.7) |

Women with morbidly adherent placenta had a median EBL of 2000 mL, an unanticipated surgical procedure in 78.5% of cases, and were admitted to the ICU approximately one-third of the time (Table 2). Thirty percent of women (n=48) with morbidly adherent placenta did not undergo a hysterectomy. Of the women not undergoing a hysterectomy, treatments included uterine artery ligation (n=1), hypogastric artery ligation (n=1), balloon tamponade (n=5), B-Lynch suture (n=3), two or more uterotonics (carboprost, methergine, or misoprostil) (not including oxytocin) (n=17), one uterotonic (not including oxytocin) (n=16), and dilation and curettage (n=14). Ten had none of the above treatments during their delivery hospitalization.

Table 2.

Maternal and neonatal outcomes in the morbidly adherent placenta patients (n=158), and by whether or not morbidly adherent placenta was suspected prior to delivery

| All morbidly adherent placenta | Morbidly adherent placenta suspected prior to delivery, n=84 | Morbidly adherent placenta not suspected prior to delivery, n=74 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%, 95%CI) unless otherwise noted | P-value | |||

| Maternal outcomes | ||||

| ICU admission | 49 (31.0, 23.8-38.2) | 33 (39.3, 28.8-49.7) | 16 (21.6, 12.2-31.0) | .02 |

| EBL, mL, median (interquartile range) | 2000 (1100-2800) | 2000 (1300-3000) | 1500 (1000-2500) | .004 |

| EBL, mL | .03 | |||

| Quartile 1 (≤ 1099) | 36 (23.4, 16.7-30.1) | 12 (15.0, 7.2-22.8) | 24 (32.4, 21.8-43.1) | |

| Quartile 2 (1100 – 1899) | 40 (26.0, 19.1-32.9) | 19 (23.8, 14.4-33.1) | 21 (28.4, 18.1-38.7) | |

| Quartile 3 (1900 – 2749) | 38 (24.7, 17.9-31.5) | 23 (28.8, 18.8-38.7) | 15 (20.3, 11.1-29.4) | |

| Quartile 4 (≥ 2750) | 40 (26.0, 19.1-32.9) | 26 (32.5, 22.2-42.8) | 14 (18.9, 10.0-27.8) | |

| Blood product transfused | 105 (66.5, 59.1-73.8) | 67 (79.8, 71.2-88.4) | 38 (51.4, 40.0-62.7) | <.001 |

| Among transfused, units transfused, median (interquartile range) | ||||

| Packed red blood cells | 4 (2-8) | 4 (2-9) | 4 (2-6) | .46 |

| Fresh frozen plasma | 0 (0-4) | 0 (0-5) | 0 (0-3) | .33 |

| Cryoprecipitate | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-0) | .24 |

| Platelets | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-1) | 0 (0-0) | .49 |

| Lowest postpartum hemoglobin, g/dL, median (interquartile range) | 8.0 (7.0-9.6) | 8.0 (6.6-9.4) | 8.1 (7.2-9.6) | .42 |

| Any two systolic blood pressures < 80 at least 30 minutes apart | 11 (7.0, 3.0-10.9) | 6 (7.1, 1.6-12.7) | 5 (6.8, 1.0-12.5) | .92 |

| In those with systolic blood pressure <80, lowest systolic blood pressure, mmHg, median (interquartile range) | 70 (60-76) | 71 (60-74) | 64 (64-76) | .93 |

| Any two diastolic blood pressures < 50 at least 30 minutes apart | 69 (43.7, 35.9-51.4) | 37 (44.1, 33.4-54.7) | 32 (43.2, 32.0-54.5) | .92 |

| In those with diastolic blood pressure <50, lowest diastolic blood pressure, mmHg, median (interquartile range) | 41 (33-44) | 40 (33-43) | 41 (34-44) | .73 |

| Length of maternal stay, days, median (interquartile range) | 4 (3-5) | 4 (4-6) | 4 (3-4) | <.001 |

| Maternal ventilator use in ICU | 24 (15.2, 9.6-20.8) | 18 (21.4, 12.7-30.2) | 6 (8.1, 1.9-14.3) | .02 |

| Hysterectomy | 110 (69.6, 62.5-76.8) | 77 (91.7, 85.8-97.6) | 33 (44.6, 33.3-55.9) | <.001 |

| Unanticipated maternal surgeries (excluding hysterectomy) | 28 (17.7, 11.8-23.7) | 8 (9.5, 3.3-15.8) | 20 (27.0, 16.9-37.2) | .004 |

| Maternal pulse greater than 120 beats per minutes | 40 (25.3, 18.5-32.1) | 24 (28.6, 18.9-38.2) | 16 (21.6, 12.2-31.0) | .32 |

| Neonatal outcomes | ||||

| Gestational age at delivery, weeks, median (interquartile range) | 36.6 (34.1-38.6) | 35.6 (33.6-36.9) | 37.8 (35.4-39.6) | <.001 |

| Neonatal ventilator support within 24 hours of birth | 32 (20.3, 14.0-26.5) | 24 (28.6, 18.9-38.2) | 8 (10.8, 3.7-17.9) | .006 |

| NICU admission | 80 (50.6, 42.8-58.4) | 55 (65.5, 55.3-75.6) | 25 (33.8, 23.0-44.6) | <.001 |

| Length of neonatal stay, days, median (interquartile range) | 4 (3-12) | 6 (4-14) | 4 (3-8) | .001 |

| Size for gestational age | 0.18 | |||

| Small | 22 (13.9, 8.5-19.3) | 9 (10.7, 4.1-17.3) | 13 (17.6, 8.9-26.2) | |

| Appropriate | 119 (75.3, 68.6-82.0) | 63 (75.0, 65.7-84.3) | 56 (75.7, 65.9-85.5) | |

| Large | 17 (10.8, 5.9-15.6) | 12 (14.3, 6.8-21.8) | 5 (6.8, 1.0-12.5) | |

ICU = intensive care unit; EBL = estimated blood loss; NICU = neonatal intensive care unit

Morbidly adherent placenta was suspected during pregnancy in only 53.2% (n=84) women (Table 2). Women with a morbidly adherent placenta that was suspected prior to delivery were more likely to have an ICU admission, have an EBL ≥ 2750 mL (the upper quartile of blood loss for women in the analysis), and have a hysterectomy (Table 2). There were also differences in the frequency of blood transfusion, which occurred in a majority in both groups (morbidly adherent placenta suspected [n=67, 79.8%] and not suspected [n=38, 51.4%]). The neonates of mothers whose morbidly adherent placentas were suspected prior to delivery were born at earlier gestational ages, more likely required ventilatory support, and were more likely to be admitted to the NICU and have longer lengths of stay.

Women undergoing a hysterectomy with another procedure had more ICU admissions and larger blood losses compared with women not undergoing a hysterectomy (Table 3). Women with scheduled deliveries did not show significant differences in ICU admissions or EBL >2750 mL (the highest quartile of blood loss) compared with women with unscheduled deliveries. Unscheduled deliveries were earlier when a morbidly adherent placenta was suspected than when it was not suspected (Table 4). Only deliveries that were both scheduled and with an unsuspected morbidly adherent placenta had a median gestational age beyond 37 weeks.

Table 3.

Maternal outcomes in the morbidly adherent placenta patients (n=158), by procedure or by scheduled / unscheduled delivery

| Procedure | Scheduled / unscheduled delivery | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal outcomes | Hysterectomy with other procedure*, n=20 | Hysterectomy without other procedure*, n=90 | Other procedure* without hysterectomy, n=9 | No hysterectomy and no other procedure*, n=39 | P-value | Scheduled, n=95 | Unscheduled, n=63 | P-value |

| n (%) | n (%) | |||||||

| ICU admission | 14 (70.0) | 32 (35.6) | 2 (22.2) | 1 (2.6) | <.001 | 24 (25.3) | 25 (39.7) | .06 |

| Highest quartile of EBL (≥ 2750 mL) | 10 (55.6) | 29 (33.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.6) | <.001 | 22 (23.9) | 18 (29.0) | .48 |

ICU = intensive care unit; EBL = estimated blood loss

uterine artery ligation, hypogastric artery ligation, B lynch suture, uterine balloon tamponade

Table 4.

Gestational age at delivery in the morbidly adherent placenta patients (n=158), by scheduled /unscheduled delivery and by whether or not morbidly adherent placenta was suspected prior to delivery

| Scheduled and suspected, n=53 | Scheduled and not suspected, n=42 | Unscheduled and suspected, n=31 | Unscheduled and not suspected, n=32 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational age at delivery, weeks, median (interquartile range) | 36.6 (35.4-37.1) | 39.0 (37.0-39.6) | 33.6 (30.6-34.9) | 36.6 (32.9-39.2) |

| Gestational age at delivery, n (%) | ||||

| < 34 weeks | 6 (11.3) | 2 (4.8) | 19 (61.3) | 12 (37.5) |

| 34-36 weeks | 29 (54.7) | 8 (19.1) | 9 (29.0) | 7 (21.9) |

| 37+ weeks | 18 (34.0) | 32 (76.2) | 3 (9.7) | 13 (40.6) |

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated that among 25 hospitals affiliated with academic medical centers, morbidly adherent placenta occurs at a frequency of 1 per 731 births. The occurrence of a morbidly adherent placenta is associated with substantial morbidity, with the majority of women requiring blood transfusion, undergoing unanticipated surgery, and more than one-third being admitted to the ICU. Our cohort has a lower proportion of morbidly adherent placentas than has been reported in recent literature.1, 2 This finding could be explained by the fact that previous reports are from referral centers with particularly high rates of morbidly adherent placenta and may not reflect the actual population frequency. Indeed, given that many of the hospitals in this study were tertiary care referral centers, it is likely that our estimated prevalence is also greater than the general population risk. Variation in the frequency of morbidly adherent placenta in various hospitals likely reflects referral patterns in various cities. Additional, we may have variation from other studies in that we did not have detailed pathology reports available to us. However, if we required pathology reports, we would bias our sample towards only those morbidly adherent placentas managed with hysterectomy and miss the 30% that were managed without hysterectomy. Variation from previous studies on placenta accreta from the MFMU are because previous studies were limited only to women having cesarean deliveries and thus biased towards women suspected of having morbidly adherent placentas known prior to delivery.

While many women with morbidly adherent placentas fit the traditional description of a multiparous woman with prior cesarean, many did not. Women having their first baby composed close to 1/5 of the morbidly adherent placenta population and 44% had no more than 1 prior delivery >20 weeks of gestation. These findings underscore the importance of recognizing that morbidly adherent placenta can occur even in women otherwise thought to be very low risk for this complication by their parity.

The significant morbidity incurred by women with a morbidly adherent placenta suspected prior to delivery (half of the cases) may be due to the fact that these morbidly adherent placentas are more deeply invasive and more evident on prenatal imaging modalities. This result emphasizes that these women are at particularly high risk of adverse outcomes and should be managed in centers with capability for massive blood transfusion with experienced intensivists and surgeons.3

Interestingly, a significant number of morbidly adherent placentas were unsuspected before delivery even at larger tertiary care centers. Our findings would suggest that routine obstetrical care, including some ultrasound, is not sensitive for detecting morbidly adherent placentas. However, we did not have detailed ultrasound reports available to us for this study.

It is striking that 30% of women diagnosed with morbidly adherent placenta in this sample were managed without hysterectomy. We do not have information on whether these women had focal resections of the uterine wall or whether the placentas were left in situ. Further investigation into the advisability of conservative measures and the patients’ long term outcomes is warranted. Because our data only included the delivery hospitalization, the possibility of long term complications was not captured.

In sum, previous estimates of the frequency of morbidly adherent placenta may be over-stated. Eighteen percent of women with morbidly adherent placenta are nulliparous and only 53.2 % of all morbidly adherent placentas were suspected prior to delivery. Thus all hospitals need to be prepared to handle this emergency. Nevertheless, women who do have morbidly adherent placenta suspected before delivery have worse outcomes, and should be considered at particularly high risk of morbidity and triaged appropriately.

Supplementary Material

Precis.

Eighteen percent of women with morbidly adherent placenta are nulliparous; women having morbidly adherent placenta suspected antenatally experience worse outcomes and should be considered at high risk for morbidity.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) [HD21410, HD27869, HD27915, HD27917, HD34116, HD34208, HD36801, HD40500, HD40512, HD40544, HD40545, HD40560, HD40485, HD53097, HD53118] and the National Center for Research Resources [UL1 RR024989; 5UL1 RR025764]. Comments and views of the authors do not necessarily represent the official views of the NICHD or NCRR.

Sponsored by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units (MFMU) Network.

The authors thank Cynthia Milluzzi, RN and Joan Moss, RNC, MSN, for protocol development and coordination between clinical research centers; Elizabeth Thom, Ph.D, for protocol/data management and statistical analysis; and Brian M. Mercer, MD, and Catherine Y. Spong, MD, for protocol development and oversight.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Belfort MA. Placenta accreta. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2010;203:430–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu S, Kocherginsky M, Hibbard JU. Abnormal placentation: twenty-year analysis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2005;192:1458–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.12.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ACOG Committee opinion no. 529: placenta accreta. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:207–11. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318262e340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wright JD, Pri-Paz S, Herzog TJ, et al. Predictors of massive blood loss in women with placenta accreta. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2011;205:38, e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gielchinsky Y, Mankuta D, Rojansky N, Laufer N, Gielchinsky I, Ezra Y. Perinatal outcome of pregnancies complicated by placenta accreta. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:527–30. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000136084.92846.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silver RM, Landon MB, Rouse DJ, et al. Maternal Morbidity Associated With Multiple Repeat Cesarean Deliveries. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2006;107:1226–32. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000219750.79480.84. 10.097/01.AOG.0000219750.79480.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bailit JL, Grobman WA, Rice MM, et al. Risk-adjusted models for adverse obstetric outcomes and variation in risk-adjusted outcomes across hospitals. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2013;209:446, e1–46, e30. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duryea EL1, Hawkins JS, McIntire DD, Casey BM, Leveno KJ. A revised birth weight reference for the United States. Obstet Gynecol. Jul. 2014;124(1):16–22. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.