Abstract

Background

Preclinical studies suggest that Reed–Sternberg cells exploit the programmed death 1 (PD-1) pathway to evade immune detection. In classic Hodgkin's lymphoma, alterations in chromosome 9p24.1 increase the abundance of the PD-1 ligands, PD-L1 and PD-L2, and promote their induction through Janus kinase (JAK)–signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) signaling. We hypothesized that nivolumab, a PD-1–blocking antibody, could inhibit tumor immune evasion in patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin's lymphoma.

Methods

In this ongoing study, 23 patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin's lymphoma that had already been heavily treated received nivolumab (at a dose of 3 mg per kilogram of body weight) every 2 weeks until they had a complete response, tumor progression, or excessive toxic effects. Study objectives were measurement of safety and efficacy and assessment of the PDL1 and PDL2 (also called CD274 and PDCD1LG2, respectively) loci and PD-L1 and PD-L2 protein expression.

Results

Of the 23 study patients, 78% were enrolled in the study after a relapse following autologous stem-cell transplantation and 78% after a relapse following the receipt of brentuximab vedotin. Drug-related adverse events of any grade and of grade 3 occurred in 78% and 22% of patients, respectively. An objective response was reported in 20 patients (87%), including 17% with a complete response and 70% with a partial response; the remaining 3 patients (13%) had stable disease. The rate of progression-free survival at 24 weeks was 86%; 11 patients were continuing to participate in the study. Reasons for discontinuation included stem-cell transplantation (in 6 patients), disease progression (in 4 patients), and drug toxicity (in 2 patients). Analyses of pretreatment tumor specimens from 10 patients revealed copy-number gains in PDL1 and PDL2 and increased expression of these ligands. Reed–Sternberg cells showed nuclear positivity of phosphorylated STAT3, indicative of active JAK-STAT signaling.

Conclusions

Nivolumab had substantial therapeutic activity and an acceptable safety profile in patients with previously heavily treated relapsed or refractory Hodgkin's lymphoma. (Funded by Bristol-Myers Squibb and others; ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT01592370.)

The Programmed Death 1 (PD-1) pathway serves as a checkpoint to limit T-cell–mediated immune responses.1 Both PD-1 ligands, PD-L1 and PD-L2, engage the PD-1 receptor and induce PD-1 signaling and associated T-cell “exhaustion,” a reversible inhibition of T-cell activation and proliferation.1 By expressing PD-1 ligands on the cell surface and engaging PD-1 receptor–positive immune effector cells, tumors can co-opt the PD-1 pathway to evade an immune response.2

PD-1–blocking antibodies have been used to enhance immunity in solid tumors and obtain durable clinical responses with an acceptable safety profile.2-5 Preliminary data also support empirical PD-1 blockade as a therapeutic strategy in certain hematologic cancers.6-12 Adverse events that are commonly associated with PD-1–blocking antibodies include pruritus, rash, and diarrhea.4 Immune-mediated pneumonitis, colitis, hepatitis, hypophysitis, and thyroiditis are less common toxic effects of PD-1 blockade.4,13

Classic Hodgkin's lymphomas include small numbers of malignant Reed–Sternberg cells within an extensive but ineffective inflammatory and immune-cell infiltrate.14,15 The genes encoding the PD-1 ligands, PDL1 and PDL2 (also called CD274 and PDCD1LG2, respectively), are key targets of chromosome 9p24.1 amplification, a recurrent genetic abnormality in the nodular-sclerosis type of Hodgkin's lymphoma.14 The 9p24.1 amplicon also includes JAK2, and gene dose–dependent JAK-STAT activity further induces PD-1 ligand transcription.14 These copy-number–dependent mechanisms and less frequent chromosomal rearrangements16 lead to overexpression of the PD-1 ligands on Reed–Sternberg cells in patients with Hodgkin's lymphoma. Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection also increases the expression of PD-1 ligands in EBV-positive Hodgkin's lymphomas.17

The complementary mechanisms of PD-1 ligand overexpression in Hodgkin's lymphoma suggest that this disease may have genetically determined vulnerability to PD-1 blockade. Coamplification of PDL1 and PDL2 on chromosome 9p24.1 suggests receptor rather than selective ligand blockade as a treatment strategy. For these reasons, Hodgkin's lymphoma was included as a cohort-expansion group in a phase 1 study of nivolumab (Bristol-Myers Squibb and Ono Pharmaceutical), a fully human monoclonal IgG4 antibody directed against PD-1, in patients with relapsed or refractory hematologic cancer.

Methods

Patients

To be eligible for participation in this study, patients had to be at least 18 years of age, have histologically confirmed evidence of relapsed or refractory Hodgkin's lymphoma with at least one lesion measuring more than 1.5 cm (as defined by the Revised Response Criteria for Malignant Lymphomas18) (see the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org), an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG)19 performance-status score of 0 or 1 (on a scale from 0 to 5, with 0 indicating no symptoms and higher scores indicating increasing disability), previous treatment with at least one chemotherapy regimen, and no autologous stem-cell transplantation within the previous 100 days. Key exclusion criteria were a history of cancer involving the central nervous system, a history of or active autoimmune disease, a concomitant second cancer, and previous organ allograft or allogeneic bone marrow transplantation.

Study Design

This phase 1 study consisted of dose-escalation and expansion cohorts. In the dose-escalation cohort, patients with relapsed or refractory hematologic cancers were treated with nivolumab at a dose of 1 mg per kilogram of body weight, with escalation of the dose to 3 mg per kilogram. Since the maximum tolerated dose was not reached, a dose of 3 mg per kilogram was chosen for the expansion cohorts. Patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin's lymphoma received nivolumab at a dose of 3 mg per kilogram at week 1, week 4, and then every 2 weeks until disease progression or complete response or for a maximum of 2 years.

The primary objective was to evaluate the safety and side-effect profile of nivolumab. Secondary objectives included characterizing the efficacy of nivolumab and assessing PD-1 ligand loci integrity and expression of the encoded ligands.

Adverse events were assessed throughout the study and for 100 days after the last dose was administered, according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.20 Patients were evaluated for efficacy at weeks 4, 8, 16, and 24 and every 16 weeks thereafter. All the patients underwent computed tomography (CT) and 18F-fluorodeoxy-glucose–positron-emission tomography (FDG-PET) at screening, subsequent CT (as described above), and FDG-PET scanning for confirmation of a complete response.

Study Oversight

The protocol was approved by the institutional review board at each center, and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonisation Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice. All the patients provided written informed consent before study entry. The principal investigators, in collaboration with the sponsor (Bristol-Myers Squibb), were responsible for the design and oversight of the study and development of the protocol, available at NEJM.org. The sponsor was responsible for the collection and maintenance of the data. Initial drafts of the manuscript were prepared by the authors, with subsequent editorial assistance paid for by the sponsor. All the authors made the decision to submit the manuscript for publication and vouch for the accuracy and completeness of the data reported and adherence to the protocol.

Biomarker Assessment

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) was performed on Hodgkin's lymphoma tissue sections to assess copy number on chromosome 9p24.1. The bacterial artificial chromosome probes (CHORI; www.chori.org) RP11-599H2O, which maps to 9p24.1 and includes CD274 (encoding PD-L1, labeled with Spectrum Orange), and RP11-635N21, which also maps to 9p24.1 and includes PDCD1LG2 (encoding PD-L2, labeled with Spectrum Green), were cohybridized. A control centromeric probe, Spectrum Aqua–labeled CEP9 (Abbott Molecular) that maps to 9p11-q11, was hybridized according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Malignant Reed–Sternberg cells were identified by means of nuclear morphologic features, and all such cells were analyzed. Nuclei with a target:control probe ratio of at least 3:1 were classified as amplified, those with a probe ratio of more than 1:1 but less than 3:1 were classified as relative copy gain, and those with a probe ratio of 1:1 but with more than two copies of each probe were classified as polysomic for chromosome 9p. Immunohistochemical staining was performed by means of an automated staining system (BOND-III, Leica Biosystems), with the use of a double-staining technique for PD-L1 (405.9A11) and PAX5 (24/Pax-5, BD Biosciences), and for PD-L2 (366C.9E5) and phosphorylated STAT3 (pSTAT3; D3A7, Cell Signaling Technology). The methods are detailed in the Supplementary Appendix.

Statistical Analysis

All the patients who received at least one dose of nivolumab were included in the safety and efficacy analyses. The database was locked on June 16, 2014. Adverse effects were coded with the use of the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities, version 17.0, and tabulated.

The principal investigator at each site evaluated efficacy assessments using the Revised Response Criteria for Malignant Lymphomas18 (see the Supplementary Appendix). The best overall response was defined as the best response between the date of the first dose and the last efficacy assessment before subsequent therapy. The objective response rate was defined as the proportion of the total number of patients whose best overall response was either a partial or a complete response. A complete response was defined as tumor regression to 1.5 cm or less in greatest diameter, if the tumor measured more than 1.5 cm before therapy, or a decrease in previously involved nodes measuring 1.1 to 1.5 cm in greatest diameter to 1 cm or less or a decrease of more than 75%, with negative results on PET scanning (see the Supplementary Appendix).

Progression-free survival was defined as the time from the date of the first dose of study medication to the date of first disease progression or the date of death. Progression-free survival was estimated with the use of Kaplan–Meier methods. The time to a response was defined as the time from the date of the first dose to the date of the first response. The duration of a response was defined as the time between the date of the first response and the date of first progression or the date of death. Plots of the percentage changes in tumor burden over time for each patient are presented graphically.

Results

Patients

Since enrollment started in August 2012, a total of 23 patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin's lymphoma have been enrolled in the study. Results are reported through June 16, 2014. The baseline characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 1. The median age was 35 years (range, 20 to 54), and 17 patients (74%) had an ECOG performance-status score of 1. All the patients had been extensively pretreated, with 87% having received three or more previous treatment regimens; 78% of the patients had received brentuximab vedotin (hereafter referred to as brentuximab) previously, and 78% had undergone autologous stem-cell transplantation. Extranodal disease involving bone, lung, pelvis, peritoneum, or pleura was found in 17% of the patients. With one exception, all the patients had the nodular-sclerosis type of Hodgkin's lymphoma; the remaining patient had mixed cellularity. The most common first-line chemotherapy was ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine), which was administered in 20 patients (87%).

Table 1. Characteristics of the 23 Patients at Baseline.

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age — yr | |

| Median | 35 |

| Range | 20–54 |

| Male sex — no. (%) | 12 (52) |

| Race — no. (%)☆ | |

| White | 20 (87) |

| Black | 2 (9) |

| Other | 1 (4) |

| ECOG performance-status score — no. (%)† | |

| 0 | 6 (26) |

| 1 | 17 (74) |

| Histologic findings — no. (%) | |

| Nodular sclerosis | 22 (96) |

| Mixed cellularity | 1 (4) |

| No. of previous systemic therapies — no. (%) | |

| 2 or 3 | 8 (35) |

| 4 or 5 | 7 (30) |

| ≥6 | 8 (35) |

| Previous treatment — no. (%) | |

| Brentuximab vedotin | 18 (78) |

| Autologous stem-cell transplantation | 18 (78) |

| Radiotherapy | 19 (83) |

| Extranodal involvement — no. (%)‡ | 4 (17) |

Race was either self-reported or reported by investigators.

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) scores indicate the performance status of patients with respect to activities of daily living on a scale from 0 to 5, with higher numbers indicating greater disability. A score of 0 indicates that the patient is fully active and able to carry out all predisease activities without restriction, and a score of 1 indicates that the patient is restricted in physically strenuous activity but is ambulatory and able to carry out work of a light nature.

Sites of extranodal disease were bone, lung, pelvis, peritoneum, and pleura.

Safety

Among the 23 patients, adverse events of any grade were reported in 22 (96%). Grade 3 or 4 adverse events occurred in 12 patients (52%). Grade 3, 4, or 5 adverse events, listed according to whether they were deemed by the investigators to be related or unrelated to the study drug, are included in Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix. Drug-related adverse events that occurred in at least 5% of the patients are listed in Table 2. Overall, drug-related adverse events were reported in 18 patients (78%). The most common were rash (in 22%) and a decreased platelet count (in 17%). Drug-related grade 3 adverse events, which were reported in 5 patients (22%), included the myelodysplastic syndrome, pancreatitis, pneumonitis, stomatitis, colitis, gastrointestinal inflammation, thrombocytopenia, an increased lipase level, a decreased lymphocyte level, and leukopenia. There were no drug-related grade 4 or 5 adverse events. Three patients had one serious drug-related adverse event each (grade 3 pancreatitis, grade 3 myelodysplastic syndrome, and grade 2 lymph-node pain) (Table 2). The patient with the myelodysplastic syndrome had undergone six previous systemic chemotherapies, radiation therapy, and autologous stem-cell transplantation but had not received bendamustine previously. There were no treatment-related deaths.

Table 2. Drug-Related Adverse Events in the 23 Patients☆.

| Event | Any Grade | Grade 3 |

|---|---|---|

| no. of patients (%) | ||

| Any adverse event | 18 (78) | 5 (22) |

| Drug-related adverse events reported in ≥5% of patients | ||

| Rash | 5 (22) | 0 |

| Decreased platelet count | 4 (17) | 0 |

| Fatigue | 3 (13) | 0 |

| Pyrexia | 3 (13) | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 3 (13) | 0 |

| Nausea | 3 (13) | 0 |

| Pruritus | 3 (13) | 0 |

| Cough | 2 (9) | 0 |

| Hypothyroidism | 2 (9) | 0 |

| Decreased lymphocyte count | 2 (9) | 1 (4) |

| Hypophosphatemia | 2 (9) | 0 |

| Hypercalcemia | 2 (9) | 0 |

| Increased lipase level | 2 (9) | 1 (4) |

| Stomatitis | 2 (9) | 1 (4) |

| Drug-related serious adverse events | ||

| Myelodysplastic syndrome | 1 (4) | 1 (4) |

| Lymph-node pain | 1 (4) | 0 |

| Pancreatitis | 1 (4) | 1 (4) |

No grade 4 or grade 5 drug-related adverse events were reported. Decisions about whether the adverse event was related to the study drug were made by the investigators. A more detailed list of adverse events is provided in Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix.

Of the 12 patients (52%) who discontinued treatment, 2 patients (9%) had toxic effects (the myelodysplastic syndrome and thrombocytopenia in 1 patient and pancreatitis in 1 patient), 4 patients (17%) had progressive disease during treatment, and 6 patients (26%) elected to undergo either allogeneic stem-cell transplantation (in 5 patients) or autologous stem-cell transplantation (in 1). Adverse events were reversible in all the patients except the 2 who discontinued treatment. As of June 16, 2014, a total of 11 patients (48%) were continuing to participate in the study.

The median number of nivolumab doses that patients received was 16 (range, 6 to 37), administered over a median treatment duration of 36 weeks (range, 13 to 77), with 15 patients (65%) receiving 90% or more of the intended overall dose. Nine patients (39%) had at least one dose delay (five delays because of nonhematologic drug-related adverse events, five delays because of infections unrelated to treatment, and one delay because of inclement weather). All the patients who had delayed doses were able to restart treatment. Two patients (9%) had infusion interruptions that were due to grade 1 hypersensitivity reactions.

Clinical Activity

The response rate was 87% (95% confidence interval [CI], 66 to 97), with a complete response occurring in 4 patients (17%), a partial response in 16 patients (70%), and stable disease in 3 patients (13%) (Table 3). Of the 4 patients with complete responses, 3 had not received previous treatment with brentuximab. Results are also summarized according to three subgroups: patients in whom previous autologous stem-cell transplantation and brentuximab treatment failed, those in whom brentuximab treatment had failed but who did not undergo autologous stem-cell transplantation before brentuximab treatment, and those who did not receive brentuximab (Table 3). Among 15 patients who had disease recurrence after autologous stem-cell transplantation and brentuximab treatment, the response rate was 87% (95% CI, 60 to 98). Of these patients, 1 (7%) had a complete response, 12 (80%) had a partial response, and 2 (13%) had stable disease. For the 3 patients who did not undergo autologous stem-cell transplantation before brentuximab treatment, the response rate was 100% (95% CI, 29 to 100), with all 3 patients having a partial response. Among the 5 patients who did not receive brentuximab, the response rate was 80% (95% CI, 28 to 99), with 3 patients (60%) having a complete response, 1 (20%) a partial response, and 1 (20%) stable disease.

Table 3. Clinical Activity in Nivolumab-Treated Patients.☆.

| Variable | All Patients (N = 23) | Failure of Both Stem-Cell Transplantation and Brentuximab (N = 15) | No Stem-Cell Transplantation and Failure of Brentuximab (N = 3) | No Brentuximab Treatment (N = 5)† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Best overall response — no. (%) | ||||

| Complete response | 4 (17) | 1 (7) | 0 | 3 (60) |

| Partial response | 16 (70) | 12 (80) | 3 (100) | 1 (20) |

| Stable disease | 3 (13) | 2 (13) | 0 | 1 (20) |

| Progressive disease | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Objective response | ||||

| No. of patients | 20 | 13 | 3 | 4 |

| Percent of patients (95% CI) | 87 (66–97) | 87 (60–98) | 100 (29–100) | 80 (28–99) |

| Progression-free survival at 24 wk — % (95% CI)‡ | 86 (62–95) | 85 (52–96) | NC§ | 80 (20–97) |

| Overall survival — wk | ||||

| Median | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Range at data cutoff¶ | 21–75 | 21–75 | 32–55 | 30–50 |

NC denotes not calculated, and NR not reached.

In this group, two patients had undergone autologous stem-cell transplantation and three had not.

Point estimates were derived from Kaplan–Meier analyses; 95% confidence intervals were derived from Greenwood's formula.

The estimate was not calculated when the percentage of data censoring was above 25%.

Responses were ongoing in 11 patients.

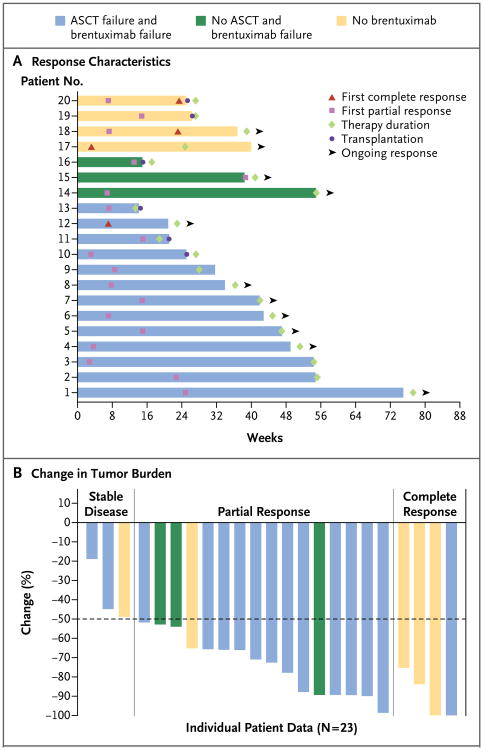

Of the 20 patients who had a complete or partial response, 12 patients (60%) had the first response by 8 weeks (range, 3 to 39 weeks) (Fig. 1A). The rate of progression-free survival at 24 weeks was 86% (95% CI, 62 to 95). As of this writing, 6 patients chose to undergo stem-cell transplantation at the time of the best overall response, and 11 patients continued to have a response (Fig. 1A). The median overall survival had not been reached. The median duration of follow-up was 40 weeks (range, 0 to 75).

Figure 1. Response Characteristics and Changes in Tumor Burden in Patients with Hodgkin's Lymphoma Receiving Nivolumab.

Panel A shows the response onset and duration for the 20 study patients who had a response to treatment with nivolumab. The color of each bar indicates whether previous autologous stem-cell transplantation (ASCT) or brentuximab therapy had failed in that patient. The length of the bar shows the time until the patient had a complete response or a partial response, along with the duration of the response. Six patients elected to discontinue the study in order to undergo stem-cell transplantation after having a response to nivolumab. Eleven patients continued to have a response at the time of this writing (indicated by an arrowhead). Panel B shows the percentage reduction in tumor burden from baseline in all 23 study patients. Two patients met the criteria for a complete response without having a 100% decrease in tumor burden. One patient with a partial response had a 99% decrease in tumor burden but had positive results on positron-emission tomography.

Figure 1B shows the maximum reduction in tumor burden from baseline for each patient. Progression-free survival for the entire cohort is shown in Figure S1 in the Supplementary Appendix.

Analysis of PD-1 Ligand Loci and Expression

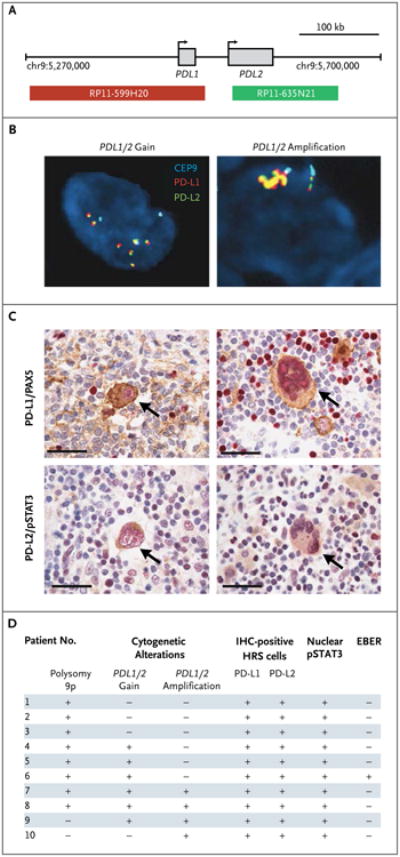

In the subgroup of 10 patients with available tumor samples, PDL1 and PDL2 copy numbers in Reed–Sternberg cells were assessed with the use of fixed tumor-biopsy specimens and a three-probe FISH assay (PDL1 [CD274], PDL2 [PDCD1LG2], and control centromeric probe) (Fig. 2A). In all tumors analyzed by means of FISH, tumor cells had 3 to 15 copies of PDL1 and PDL2 in patterns characterized by amplification, relative copy gain, or polysomy of chromosome 9p (Fig. 2D, and Table S2 and Fig. S2 in the Supplementary Appendix). In all the samples, Reed–Sternberg cells, which were identified by their characteristic morphologic features and staining for PAX5, expressed PD-L1 and PD-L2 proteins (Fig. 2C and 2D, and Table S3 and Fig. S2 in the Supplementary Appendix). Tumor cells were also positive for nuclear pSTAT3, indicative of active JAK-STAT signaling (Fig. 2C and 2D, and Table S3 and Fig. S2 in the Supplementary Appendix). Infiltrating T cells in the available Hodgkin's lymphoma biopsy specimens largely expressed low levels of the PD-1 receptors (Table S4 and Fig. S3 in the Supplementary Appendix). Together, these data indicate that all the patients with Hodgkin's lymphoma in this study who could be evaluated had numeric alterations of the PD-1 ligand loci and associated protein expression.

Figure 2. Genetic and Immunohistochemical Analyses of PDL1 and PDL2 Loci, PD-L1 and PD-L2 Protein Expression, and Epstein–Barr Virus Status in Patients with Hodgkin's Lymphoma.

Shown are the results of analyses of the PDL1 and PDL2 loci and PD-L1 and PD-L2 protein expression in Reed–Sternberg cells. Panel A shows the location and color labeling of bacterial artificial chromosome clones used for the fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) assay for PDL1 (red) and PDL2 (green) on chromosome 9p24.1. Representative images obtained from patients show a copy-number gain in PDL1 and PDL2 (Panel B, left), with six green–red (yellow overlap) signals (signifying a fusion signal), as compared with three centromeric signals (aqua), or PDL1 and PDL2 amplification (Panel B, right), with more than three times as many green–red (yellow overlap) signals as centromeric signals (aqua). In Panel C, the expression of PD-L1 (upper row) and PD-L2 (lower row) is indicated by brown staining in Reed–Sternberg cells obtained from the same patients as in Panel B. Arrows indicate malignant cells. PD-L1 is evaluated in conjunction with PAX5 to identify PAX5-positive cells (shown in red in the upper row). PD-L2 is assessed in association with phosphorylated signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (pSTAT3), which reflects Janus kinase–STAT activation (shown in red in the lower row). The scale bars represent 50 μm. Panel D shows PD-L1 and PD-L2 protein expression and status with respect to Epstein–Barr virus–encoded messenger RNA (EBER) in study patients who could be evaluated. All the patients who were included in the analysis had structural bases for increased copy numbers in PDL1 and PDL2 on chromosome 9p24.1, including extra copies of 9p (polysomy 9p), copy gain in PDL1 or PDL2, or amplification in PDL1 or PDL2 (Table S2 and Fig. S2 in the Supplementary Appendix). Epstein–Barr virus status was evaluated by means of a FISH assay. HRS denotes Hodgkin's Reed–Sternberg, and IHC immunohistochemical.

Discussion

In this study, we found that nivolumab-mediated PD-1 blockade was a highly effective therapy in patients with Hodgkin's lymphoma, a disease with a genetic basis for PD-1 ligand overexpression and a marked but ineffective inflammatory and immune-cell infiltrate. In heavily pretreated patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin's lymphoma, the majority of whom had had a relapse after autologous stem-cell transplantation and brentuximab treatment, the use of nivolumab was associated with an overall response rate of 87% and a rate of progression-free survival of 86% at 24 weeks. Adverse events were mainly of grade 1 or 2. The rate of adverse events was similar to that in trials of nivolumab in patients with solid tumors.4 Given the limited therapeutic options for patients with Hodgkin's lymphoma whose disease progresses after autologous stem-cell transplantation21-23 and the relatively short-lived responses to brentuximab after relapse,24 nivolumab-mediated PD-1 blockade may represent a promising targeted treatment for these patients.

The frequent chromosome 9p24.1 amplification and associated PD-1 ligand overexpression in Hodgkin's lymphoma and the pronounced but ineffective inflammatory response seen in involved lymph nodes provided a compelling rationale for evaluating the efficacy of PD-1 blockade in patients with relapsed or refractory disease. In this study, all the patients with available tumor specimens had concurrent gain of the PDL1 and PDL2 loci, increased expression of the PD-1 ligands, and evidence of active JAK-STAT signaling. In this group of patients, the incidence of a copy-number gain in PDL1 and PDL2 was higher than in previously reported series of patients with newly diagnosed Hodgkin's lymphoma,14,25 suggesting that this disease-specific genetic alteration may have adverse prognostic significance. The low rate of EBV positivity (1 of 10 patients) that was observed is consistent with the low predominance of EBV in Hodgkin's lymphoma of the nodular-sclerosis type.26

In available biopsy samples obtained from the patients, tumor-infiltrating T cells largely expressed low levels of PD-1 on standard immunohistochemical analysis. Previous studies have suggested that PD-1 blockade selectively enhances the function of CD8+ T cells that have low or intermediate, rather than high, levels of PD-1 expression.27 The levels of PD-1 on tumorinfiltrating T cells were significantly less predictive of response to nivolumab therapy than was PD-L1 expression on solid tumors in recent clinical trials,6 findings that are consistent with our results.

The frequent clinical responses to nivolumab therapy in heavily pretreated patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin's lymphoma and genetic alterations of the PD-1 ligand loci high-light the importance of the PD-1 immune evasion pathway and the genetically defined sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in this disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by Bristol-Myers Squibb, by grants from the National Institutes of Health (U54CA163125 and P01AI056299, to Dr. Freeman; and R01CA161026, to Dr. Shipp), and by a grant from the Miller Fund (to Dr. Shipp).

Dr. Ansell reports receiving grant support from Seattle Genetics, Celldex Therapeutics, Millennium, Idera, and Regeneron; Dr. Lesokhin, receiving consulting fees and grant support from Bristol-Myers Squibb; Dr. Halwani, receiving grant support from Seattle Genetics, Millennium, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, AbbVie, Genentech, and Bristol-Myers Squibb; Dr. Freeman, receiving royalties from patents related to PD-1, PD-L1, and PD-L2 pathways (US 6808710, US 6936704, US 7038013, US7101550, US 7432059, US 7635757, US 7638492, US 7700301, US 7709214, US 8552154, and US 8652465), which are licensed to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche, Merck, EMD Serono, Boehringer Ingelheim, Amplimmune, and Novartis; Dr. Rodig, receiving grant support from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Ventana/Roche and having a pending patent application related to anti–PD-L1 monoclonal antibodies and fragments (US 61/895,543); Ms. Zhu, Dr. Grosso, and Dr. Kim, being employees of Bristol-Myers Squibb; Dr. Timmerman, receiving grant support from Bristol-Myers Squibb; Dr. Shipp, receiving fees for serving on advisory boards from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Bayer, Gilead, Merck, Pharmacyclics, and Janssen and receiving grant support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Sanofi Aventis, and Bayer; and Dr. Armand, receiving consulting fees from Merck.

We thank the patients who participated in this study, their families, and the clinical faculty and personnel; Heather H. Sun and Heather Homer, Department of Pathology, Brigham and Women's Hospital, for providing important technical support; Christina Hartman, Katherine Lears, and Maria Mezes, Bristol-Myers Squibb, for contributing to the study design; and Michelle Daniels and Christopher Radel, inScience Communications, Springer Healthcare, for providing medical writing and editorial support.

Footnotes

Drs. Ansell and Lesokhin and Drs. Shipp and Armand contributed equally to this article.

No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

References

- 1.Keir ME, Butte MJ, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH. PD-1 and its ligands in tolerance and immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:677–704. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weber J. Immune checkpoint proteins: a new therapeutic paradigm for cancer — preclinical background: CTLA-4 and PD-1 blockade. Semin Oncol. 2010;37:430–9. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQ, et al. Safety and activity of anti–PD-L1 anti-body in patients with advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2455–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti–PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2443–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lipson EJ, Sharfman WH, Drake CG, et al. Durable cancer regression off-treatment and effective reinduction therapy with an anti-PD-1 antibody. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:462–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taube JM, Klein AP, Brahmer JR, et al. Association of PD-1, PD-1 ligands, and other features of the tumor immune microenvironment with response to anti-PD-1 therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:5064–74. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andorsky DJ, Yamada RE, Said J, Pinkus GS, Betting DJ, Timmerman JM. Programmed death ligand 1 is expressed by non-hodgkin lymphomas and inhibits the activity of tumor-associated T cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:4232–44. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Armand P, Nagler A, Weller EA, et al. Disabling immune tolerance by programmed death-1 blockade with pidilizumab after autologous hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: results of an international phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:4199–206. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.3685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berger R, Rotem-Yehudar R, Slama G, et al. Phase I safety and pharmacokinetic study of CT-011, a humanized antibody interacting with PD-1, in patients with advanced hematologic malignancies. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:3044–51. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Westin JR, Chu F, Zhang M, et al. Safety and activity of PD1 blockade by pidilizumab in combination with rituximab in patients with relapsed follicular lymphoma: a single group, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:69–77. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70551-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilcox RA, Feldman AL, Wada DA, et al. B7-H1 (PD-L1, CD274) suppresses host immunity in T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders. Blood. 2009;114:2149–58. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-216671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang ZZ, Novak AJ, Stenson MJ, Witzig TE, Ansell SM. Intratumoral CD4+CD25+ regulatory T-cell-mediated suppression of infiltrating CD4+ T cells in B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2006;107:3639–46. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keytruda (pembrolizumab) White-house Station, NJ: Merck (package insert); http://www.merck.com/product/usa/pi_circulars/k/keytruda/keytruda_pi.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Green MR, Monti S, Rodig SJ, et al. Integrative analysis reveals selective 9p24.1 amplification, increased PD-1 ligand expression, and further induction via JAK2 in nodular sclerosing Hodgkin lymphoma and primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2010;116:3268–77. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-282780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Juszczynski P, Ouyang J, Monti S, et al. The AP1-dependent secretion of galectin-1 by Reed Sternberg cells fosters immune privilege in classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:13134–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706017104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steidl C, Shah SP, Woolcock BW, et al. MHC class II transactivator CIITA is a recurrent gene fusion partner in lymphoid cancers. Nature. 2011;471:377–81. doi: 10.1038/nature09754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Green MR, Rodig S, Juszczynski P, et al. Constitutive AP-1 activity and EBV infection induce PD-L1 in Hodgkin lymphomas and posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorders: implications for targeted therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:1611–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheson BD, Pfistner B, Juweid ME, et al. Revised response criteria for malignant lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:579–86. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5:649–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Cancer Institute. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 4.0. Bethesda, MD: Department of Health and Human Services; 2009. NIH publication no. 09-7473. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Connors JM. State-of-the-art therapeutics: Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6400–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arai S, Fanale M, DeVos S, et al. Defining a Hodgkin lymphoma population for novel therapeutics after relapse from autologous hematopoietic cell transplant. Leuk Lymphoma. 2013;54:2531–3. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2013.798868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Majhail NS, Weisdorf DJ, Defor TE, et al. Long-term results of autologous stem cell transplantation for primary refractory or relapsed Hodgkin's lymphoma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12:1065–72. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Younes A, Gopal AK, Smith SE, et al. Results of a pivotal phase II study of brentuximab vedotin for patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2183–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.0410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steidl C, Telenius A, Shah SP, et al. Genome-wide copy number analysis of Hodgkin Reed-Sternberg cells identifies recurrent imbalances with correlations to treatment outcome. Blood. 2010;116:418–27. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-257345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carbone A, Gloghini A, Zanette I, Canal B, Rizzo A, Volpe R. Co-expression of Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein and vimentin in “aggressive” histological subtypes of Hodgkin's disease. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1993;422:39–45. doi: 10.1007/BF01605131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blackburn SD, Shin H, Freeman GJ, Wherry EJ. Selective expansion of a subset of exhausted CD8 T cells by alphaPD-L1 blockade. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:15016–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801497105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.