Abstract

The aim of the study is to examine rs4680 (COMT) and rs6265 (BDNF) as genetic markers of anxiety, ADHD, and tics. Parents and teachers completed a DSM-IV-referenced rating scale for a total sample of 67 children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Both COMT (p = 0.06) and BDNF (p = 0.07) genotypes were marginally significant for teacher ratings of social phobia (ηp2 = 0.06). Analyses also indicated associations of BDNF genotype with parent-rated ADHD (p = 0.01, ηp2 = 0.10) and teacher-rated tics (p = 0.04; ηp2 = 0.07). There was also evidence of a possible interaction (p = 0.02, ηp2 = 0.09) of BDNF genotype with DAT1 3′ VNTR with tic severity. BDNF and COMT may be biomarkers for phenotypic variation in ASD, but these preliminary findings remain tentative pending replication with larger, independent samples.

Keywords: Autism, Autism spectrum disorder, Anxiety, Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, Tourette syndrome, BDNF, COMT, DAT1

Introduction

Children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) exhibit extraordinary variability in behavioral presentation including the symptoms of many nonASD psychiatric disorders (e.g., Gadow et al. 2005; Gillott et al. 2001; Kanner 1943; Smalley et al. 1995; Sukhodolsky et al. 2008; Sverd 2003; Weisbrot et al. 2005); nevertheless, relatively little is known about their biological substrates (Brieber et al. 2007; Gadow et al. 2008a; Sinzig et al. 2008; Smalley et al. 2002). Because it has generally been assumed that behavioral disturbances, particularly anxiety disorder (Gillott et al. 2001), were epiphenomena of ASD pathogenesis, most genetic studies have logically focused on the core features of ASD (Grice and Buxbaum 2006; Yang and Gill 2007). However, behavioral heterogeneity in ASD may be linked in part to the same genotypes associated with other neuropsychiatric disorders (Brune et al. 2006; Cohen et al. 2003; Gadow et al. 2008b; Roohi et al. 2009; Smalley et al. 2002). For example, findings for a well-defined ASD sample suggested associations of MAO-A promoter VNTR (Roohi et al. 2009) and DAT1 3′ VNTR (Gadow et al. 2008b) polymorphisms with ADHD, anxiety, and tic symptom severity that were consistent with the results of studies of nonASD samples.

Two well-described single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) currently of interest in the pathogenesis of anxiety are Val158Met (rs4680) in the catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) gene and Val66Met (rs6265) in the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) gene (Hovatta and Barlow 2008; Smoller et al. 2008). COMT plays an important role in the catabolism of brain dopamine and norepinephrine, and Val158 and Met158 alleles are associated with high and low enzyme activity, respectively. Research generally supports the low activity Met158 allele as the risk factor for phobic anxiety, panic disorder, and OCD, but as with many candidate genes, findings are mixed (Hovatta and Barlow 2008; Smoller et al. 2008; Hettema et al. 2008; Enoch et al. 2008; Jiang et al. 2005). We are unaware of studies associating the Val158Met polymorphism with ASD, but there is modest evidence for schizophrenia (Meyer-Lindenberg and Weinberger 2006), and comorbidity analyses indicate genetic overlap for autism, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder (Rzhetsky et al. 2007).

BDNF is a neurotrophin that is involved in neuronal plasticity, neurogenesis, and response to antidepressant treatment. The Val66Met (rs6265) polymorphism is a functional BDNF SNP implicated in higher-order personality traits such as neuroticism as well as the pathogenesis of anxiety and depression (Enoch et al. 2008; Hovatta and Barlow 2008; Hünnerkopf et al. 2007; Jiang et al. 2005; Smoller et al. 2008). The Met66 allele is associated with lower BDNF secretion, but findings are mixed with regard to which variant is the susceptibility allele for anxiety. For example, there is evidence that BDNF Met66 allele is a protective factor for OCD (Hall et al. 2003), whereas others find it is a risk factor for anxiety and depression (Jiang et al. 2005). Moreover, a gene × gene interaction has been reported; specifically, individuals who were carriers of the 9-repeat DAT1 VNTR polymorphism and the BDNF Met66 allele were at less risk for neuroticism (Hünnerkopf et al. 2007). The BDNF gene has also been implicated in autism (Nishimura et al. 2007).

The primary objective of this exploratory study was to search for evidence linking gene variants (COMT Val158Met or BDNF Val66Met) purportedly implicated in the pathogenesis of anxiety in population-based and clinic-referred samples to anxiety in children with diagnosed ASD. We adopted a dimensional model for assessing anxiety owing to its statistical and conceptual advantages over the categorical or diagnostic model (Abrahams and Geschwind 2008; Belmonte et al. 2004; Szatmari et al. 2007). Specifically, we predicted a priori (before the data were analyzed) that each risk genotype would be associated with more severe anxiety symptoms. Because the results of both animal (Hovatta and Barlow 2008; Turri et al. 2001) and human (Hirshfeld et al. 2008; Hettema 2008; Hovatta and Barlow 2008; Smoller et al. 2008) studies suggest that susceptibility to different types of anxiety is likely associated at least in part with different genes, the symptoms of generalized, social, and separation anxiety disorder were examined separately. In addition, there is some preliminary evidence linking social anxiety with autism (Smalley et al. 1995). In view of prior preliminary evidence suggesting that (a) teachers rate specific symptoms of anxiety in children with ASD more severely than their mothers (Gadow et al. 2005), and (b) effect sizes for gene-anxiety associations are larger for teacher than mother ratings in children with ASD (Gadow et al. 2008b; Roohi et al. 2009), which in turn may reflect different pathogenic processes (see, for example, Ronald et al. 2008) to include reactivity to setting-specific variables, we expected that teacher versus parent report of anxiety would evidence greater genotype group differences. Our secondary objective was to determine if COMT and BDNF polymorphisms were also associated with ADHD and tic severity. This seemed reasonable because (a) prior research with different gene variants in both ASD and nonASD samples indicated pleiotropy for these symptoms (Comings et al. 1996; Gadow et al. 2008b; Roohi et al. 2009; Rowe et al. 1998), and (b) all three groups of symptoms are clearly interrelated in ASD and nonASD samples suggesting commonalities in etiology (Gadow et al. 2006; Goldstein and Schwebach 2004; Gadow and DeVincent 2005). As with anxiety symptoms, based on prior research (Gadow et al. 2008b; Roohi et al. 2009) we expected differentially larger genotype group differences for parent-rated ADHD and teacher-rated tics.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Participants in this study were recruited from referrals to a university hospital developmental disabilities specialty clinic located on Long Island, New York. All families with at least one child with a diagnosis of ASD were contacted by mail for participation in a genetic study. A total of 92 individuals were initially recruited, but to maximize homogeneity, the study sample (N = 67) was limited to individuals who were children (4–14 years old) when the diagnostic and behavioral evaluations were conducted. Parent/teacher ratings of psychiatric symptoms were available for 62/57 of the children, respectively. Demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1. This study was approved by a university Institutional Review Board, informed consent was obtained, and appropriate measures were taken to protect patient (and rater) confidentiality.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of study sample (N = 67)

| Characteristic |

COMT

|

BDNF

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metl58− (n = 11) |

Metl58+ (n = 56) |

X 2 | F | p | Met66− (n = 45) |

Met66+ (n = 22) |

X 2 | F | p | |||||

| F (%) | M (SD) | F (%) | M (SD) | F (%) | M (SD) | F (%) | M (SD) | |||||||

| Age | 8.0 (3.2) | 6.6 (2.5) | 2.56 | 0.12 | 6.6 (2.4) | 7.3 (3.0) | 0.99 | 0.32 | ||||||

| Gender (male) | 10 (91) | 48 (86) | 0.21 | 0.64 | 38 (84) | 20 (91) | 0.53 | 0.47 | ||||||

| IQ (n = 58) | 74.5 (20.8) | 78.9 (24.4) | 0.31 | 0.58 | 76.4 (24.5) | 80.9 (22.3) | 0.48 | 0.49 | ||||||

| Caucasian | 10 (91) | 54 (96) | 0.66 | 0.42 | 43 (96) | 21 (96) | 0.00 | 0.99 | ||||||

| Special ed. | 10 (91) | 46 (82) | 0.52 | 0.47 | 39 (87) | 17 (77) | 0.95 | 0.33 | ||||||

| Medication | ||||||||||||||

| Current | 3 (27) | 13 (23) | 0.08 | 0.77 | 10 (22) | 6 (27) | 0.21 | 0.65 | ||||||

| Ever | 5 (46) | 22 (39) | 0.15 | 0.70 | 20 (44) | 7 (32) | 0.98 | 0.32 | ||||||

| SES | 40.4 (13.4) | 42.8 (11.1) | 0.40 | 0.53 | 41.0 (11.0) | 45.3 (12.1) | 2.07 | 0.16 | ||||||

| Single parent | 0(0) | 1 (2) | 0.20 | 0.66 | 0(0) | 1 (5) | 2.08 | 0.15 | ||||||

| ASD subtype | 2.14 | 0.34 | 2.79 | 0.25 | ||||||||||

| Autistic | 4 (36) | 23 (41) | 21 (47) | 6 (27) | ||||||||||

| Asperger’s | 1 (9) | 14 (25) | 10 (22) | 5 (23) | ||||||||||

| PDD-NOS | 6 (55) | 19 (34) | 14 (31) | 11 (50) | ||||||||||

SES socioeconomic status assessed with Hollingshead’s (1975) index of occupational and educational social status; scores range from 24 (unskilled laborers) to 66 (major business and professionals)

Procedure

Diagnoses of ASD were made by an expert clinician with more than 20 years of clinical and research experience with ASD. These diagnoses were based on five sources of information about ASD symptoms to verify DSM-IV criteria: (a) comprehensive developmental history, (b) clinician interview with child and caregiver(s), (c) direct observations of the child, (d) review of validated ASD rating scales including the Child Symptom Inventory-4 (CSI-4) (Gadow and Sprafkin 1986, 2002; Gadow et al. 2008c; Lecavalier et al. 2009b), (e) prior evaluations, and (f) the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (Lord et al. 2000) and/or Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (Rutter et al. 2003).

Prior to scheduling their initial clinic evaluation, the parents of potential participants were mailed a packet of materials including behavior rating scales, background information questionnaire, and permission for release of school reports, psycho-educational, and special education evaluation records. Rating scales included parent and teacher versions of the CSI-4. In most cases, ratings were completed by the child’s mother. Genotype status was determined using DNA isolated from peripheral blood cells and polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Genotyping

COMT

Single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) analysis was performed for the COMT (rs4680) genotypes with high-resolution melting. PCR was carried out in a 10 μl volume containing the following primers: COMTSNPF-ACCCAGCGGATGGTGGATTT and COMTSNPR-ATGCCCTCCCTGCCCACAG. Each amplification was overlaid with mineral oil and contained 20 ng of DNA, 0.25 μM of each primer, and 1× Light Scanner Master Mix (Idaho Technology Inc). Reaction conditions were: an initial denaturation at 95°C for 2 min, followed by 53 cycles of 94°C for 30 s and 69.9°C for 30 s. Melt analysis was performed between 70 and 98°C with a Light Scanner (Idaho Technology, Inc) (Zhou et al. 2004), and SNP status determined using the Small Amplicon Module. One individual with each of the three expected genotypes (Met/Met, Met/Val, Val/Val) was sequenced to confirm correct genotype calling, and these samples were included in the melt analysis (data not shown). Genotype analyses were conducted by an investigator who was blind to the behavioral characteristics of the study sample.

BDNF

Single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) analysis was performed for the BDNF (rs6265) genotypes with high-resolution melting. PCR was carried out in a 10 μl volume containing the following primers: BDNFSNPF-TGGTCCTCATCCAACAGCTC and BDNFSNPR-CCCAAGGCAGGTTCAAGAG. Each amplification was overlaid with mineral oil and contained 20 ng of DNA, 0.25 μM of each primer, and 1× Light Scanner Master Mix (Idaho Technology Inc). Reaction conditions were an initial denaturation at 95°C for 2 min, followed by 53 cycles of 94°C for 30 s and 65°C for 30 s. Melt analysis was performed between 70 and 98°C with a Light Scanner (Idaho Technology, Inc), and SNP status determined using the Small Amplicon Module. One individual with each of the three expected genotypes (Met/Met, Met/Val, Val/Val) was sequenced to confirm correct genotype calling (data not shown).

Measures

The CSI-4 has both parent and teacher versions. Individual items bear one-to-one correspondence with DSM-IV symptoms (i.e., high content validity). To assess symptom severity, items are scored (never = 0, sometimes = 1, often = 2, and very often = 3) and summed separately for each symptom dimension. Research indicates the CSI-4 has relatively high sensitivity and specificity for identifying children with ASD (Gadow et al. 2008c) and ASD subscales demonstrate adequate internal consistency, reliability, and validity (Gadow and Sprafkin 2008). Moreover, confirmatory factor analysis in a large (N = 498) sample of children with ASD supports the construct validity of DSM-IV psychiatric syndromes (Lecavalier et al. 2009a) and the tripartite model of ASD symptom domains (Lecavalier et al. 2009b). As with all rating scales, mother and teacher ratings evidence modest convergence (Lecavalier et al. 2009b), which likely in part reflects important G × E interactions. In the present study, primary analyses pertained to generalized anxiety disorder, separation anxiety disorder (parents only), social phobia (teachers only), ADHD, and tics. Numerous studies indicate that the CSI-4 demonstrates satisfactory psychometric properties in community-based normative, clinic-referred non-ASD, and ASD samples (Gadow and Sprafkin 2008).

Statistical Analyses

Chi-square tests (categorical variables) and ANOVAs (continuous variables) were used for genotype group comparisons. Studies of the molecular genetics of neuro-behavioral syndromes invite multiple comparisons for a number of reasons to include genetic heterogeneity (i.e., different genes are associated with the same clinical phenotype in different individuals), linkage disequilibrium (i.e., nonrandom association of polymorphisms at different loci), pleiotropy (i.e., same gene affects multiple processes and consequently multiple symptoms), gene–gene interactions, and polygenic models of pathogenesis (i.e., multiple genes contribute to the clinical phenotype, each with small effects). Owing to (a) the practical and theoretical limitations of the Bonferroni correction (e.g., increased risk of making Type 2 errors) (e.g., Perneger 1998; Rothman 1990) and (b) the exploratory nature of this study, no adjustment was made for multiple comparisons. However, we report partial eta-squared (ηp2) to gauge the magnitude of obtained group differences (i.e., percentage of variance in dependent variables accounted for by independent variables). A rule of thumb for determining the magnitude of ηp2 suggests the following: 0.01–0.06 = small, 0.06–0.14 = moderate, and >0.14 = large (Cohen 1988). Moreover, we also interpret obtained findings in terms of internal consistencies within the present study and convergences with prior research.

Results

Genotypes

The distribution of COMT genotypes (frequencies/percents) was Met/Met (21/31%), Val/Met (35/52%), and Val/Val (11/17%), which does not deviate from the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (χ2 = 0.32, p >0.05). For all analyses, children homozygous for the COMT Val allele (Met158−) were compared to all others (Met158+); thus, 11 (17%) of the children fell into the COMT Met158-group, and 56 (83%) were in the COMT Met158+ group.

The distribution of BDNF genotypes (frequencies/percents) was Met/Met (4/6%), Val/Met (18/27%), and Val/Val (45/67%), which does not deviate from the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (χ2 = 1.33, p >0.05). For all analyses, children homozygous for the BDNF Val allele (Met66−) were compared to all others (Met66+); thus, 45 (67%) of the children fell into the BDNF Met66− group and 22 (33%) were in the Met66+ group.

Comparisons between the two genotype groups (for the BDNF and COMT genes separately) indicated no significant differences in age, gender, IQ, ethnicity, SES, single-parent household, special education services, ever or current medication use, or ASD subtype (Table 1).

COMT

With regard to the primary objective, there was a marginally significant (p = 0.06, ηp2 = 0.06) finding for teacher ratings of social phobia severity (Met158+ >Met158−) (Table 2), but not generalized anxiety or for parent ratings of generalized or separation anxiety dimensions. As for the secondary objective, there were no statistically significant findings for either ADHD or tics for either informant.

Table 2.

Group differences in severity of psychiatric symptoms for COMT genotypes

| Variable (CSI-4)a |

COMT Met158− Mean (SD) |

COMT Met158+ Mean (SD) |

F | p | ηp 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent ratings | |||||

| Generalized anxiety | 2.7 (2.3) | 2.8 (2.8) | 0.01 | 0.91 | 0.00 |

| Separation anxietyb | 1.6 (2.5) | 3.0 (4.0) | 0.89 | 0.35 | 0.02 |

| ADHD | 31.1 (9.8) | 28.1 (9.9) | 0.84 | 0.36 | 0.01 |

| Tics | 1.4(1.1) | 1.4 (1.6) | 0.00 | 0.96 | 0.00 |

| Teacher ratings | |||||

| Generalized anxiety | 2.2 (2.4) | 2.8 (2.3) | 0.35 | 0.56 | 0.01 |

| Social phobiac | 0.8 (0.8) | 1.9 (1.8) | 3.61 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| ADHD | 22.6 (11.2) | 24.9 (12.5) | 0.29 | 0.59 | 0.01 |

| Tics | 1.8 (1.8) | 2.1 (2.2) | 0.19 | 0.66 | 0.00 |

CSI-4 Child Symptom Inventory-4

Included in the parent version of the CSI-4 only

Owing to modifications in the item content of the CSI-4, we were unable to directly compare parent and teacher ratings of social phobia

BDNF

There was a marginally significant (p = 0.07, ηp2 = 0.06) finding for teacher ratings of social phobia severity (Met66+ >Met66−) (Table 3), but not generalized anxiety or for parent ratings of generalized or separation anxiety dimensions. The BDNF Met66− group obtained more severe parent ratings of ADHD symptoms (p = 0.01, ηp2 = 0.10) and had more severe teacher ratings of (combined motor and vocal) tics (p = 0.04, ηp2 = 0.07) than carriers of the Met66 allele.

Table 3.

Group differences in severity of psychiatric symptoms for BDNF genotypes

| Variable (CSI-4)a |

BDNF Met66− Mean (SD) |

BDNF Met66+ Mean (SD) |

F | p | ηp 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent ratings | |||||

| Generalized anxiety | 3.1 (2.9) | 2.2 (2.3) | 1.62 | 0.21 | 0.03 |

| Separation anxietyb | 2.9 (4.2) | 2.4 (2.9) | 0.11 | 0.74 | 0.00 |

| Tics | 1.7 (1.6) | 1.0 (1.2) | 2.99 | 0.09 | 0.05 |

| ADHD | 30.8 (8.6) | 24.2 (11.0) | 6.78 | 0.01 | 0.10 |

| Teacher ratings | |||||

| Generalized anxiety | 2.7 (2.4) | 2.8 (2.2) | 0.00 | 0.95 | 0.00 |

| Social phobiac | 1.4 (1.6) | 2.3 (1.9) | 3.32 | 0.07 | 0.06 |

| Tics | 2.5 (2.3) | 1.3 (1.4) | 4.31 | 0.04 | 0.07 |

| ADHD | 25.6 (13.1) | 22.2 (10.2) | 1.02 | 0.32 | 0.02 |

CSI-4 Child Symptom Inventory-4

Included in the parent version of the CSI-4 only

Owing to modifications in the item content of the CSI-4, we were unable to directly compare parent and teacher ratings of social phobia

Discussion

Unambiguous evidence linking either COMT (>Met158+) or BDNF (>Met66+) genotypes to anxiety symptom severity in children with ASD were not supported by our analyses, but at the risk of making a Type 2 error, we hasten to note that both gene variants were marginally significant for teacher ratings of social phobia (ηp2 = 0.06), and obtained findings are internally consistent (i.e., cross-gene, within-informant, within-symptom dimension). In this same sample, we have also found that teacher ratings of generalized anxiety (ηp2 = 0.12) were associated with the MAOA VNTR (Roohi et al. 2009) and social phobia (ηp2 = 0.09) with the DAT1 VNTR (Gadow et al. 2008b) polymorphisms. The school setting appears to be a stressful environment for many children with ASD likely due to the demands of social interaction (Baron-Cohen 2006; Chamberlain et al. 2007) and their innate propensity toward self-involvement, or as Kanner (1943) put it, “Everything that is brought to the child from the outside, everything that changes his external or even internal environment, represents a dreaded intrusion” (p. 244). Owing to modifications in the item content of the CSI-4, we were unable to directly compare parent and teacher ratings of social phobia. In view of compelling evidence supporting shared genetic risk factors for anxiety and depression (Hettema 2008), differentially higher rates of social phobia and depression in families of individuals with autism (Smalley et al. 1995), and associations of COMT Met158 allele with both anxiety and depression in nonASD samples (Enoch et al. 2008), we also note that teachers rated carriers of the COMT Met158 allele as having more severe depression symptoms than those in the Met158− group (p = 0.04, ηp2 = 0.07).

In the case of BDNF, others have found the risk variant to be Met66− genotype (Hünnerkopf et al. 2007), but these “flip-flop” findings are not uncommon in the literature and may ultimately be explained by an interaction between the investigational locus and other risk factors (Lin et al. 2007). Alternatively, it is also possible that ASD-related processes alter specific CNS functions such that in certain cases susceptibility alleles actually serve as an equilibration mechanism (Gadow et al. 2008b).

The secondary objective of this study was to explore possible relations between polymorphisms and ADHD and tic severity. Analyses revealed a moderate-range association between BDNF (>Met66−) genotype and parent-rated ADHD (p = 0.01, ηp2 = 0.10). Although BDNF is not considered to be a primary candidate gene for ADHD (Lee et al. 2007), there is some evidence of association (>Met66− genotype) with a cognitive ADHD endophenotype (Drtilkova et al. 2008). The consistency across genes (MAOA, ηp2 = 0.12; DAT1, ηp2 = 0.08) for associations with ADHD to be evident for parent but not teacher ratings in our sample (Roohi et al. 2009; Gadow et al. 2008b) as well as independent nonASD samples (see Thapar et al. 2006) suggests a possible gene × environment interaction.

There was a moderate-range association between BDNF genotype and teacher (p = 0.04, ηp2 = 0.07) and to lesser extent parent (p = 0.09, ηp2 = 0.05) ratings of tic severity (Met− >Met+). Hall et al. (2003) reported that the BDNF Met66 allele may be “protective” for OCD, a disorder that is generally considered to be associated with Tourette syndrome (Grados and Mathews 2008). In the present sample, neither the severity of OCD compulsion or obsession symptoms was different among genotype groups (p >0.10), thus lending support to the notion of unique risk factors for these interrelated symptoms. Our findings for BDNF are consistent with similar results for DAT1 VNTR polymorphism where teacher (but not parent) ratings were associated tic severity, and OCD symptom severity was not associated with the risk genotype (Gadow et al. 2008b).

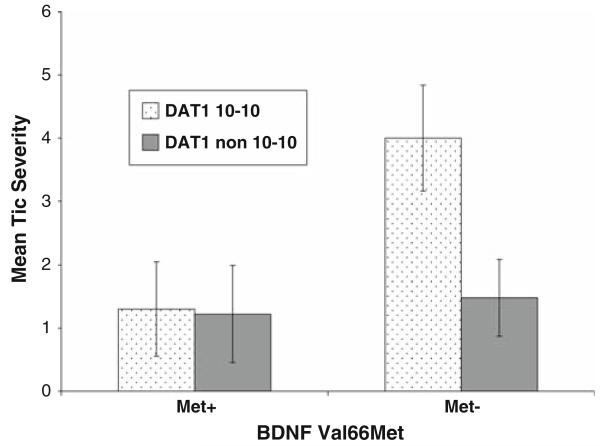

Although the study was not designed to examine gene–gene interactions, we were nevertheless curious to see if the effects of DAT1 and BDNF genotypes were additive for tic severity for three reasons. One, in our prior study of this ASD group, teacher ratings of motor and vocal tic severity were associated with DAT1 genotype (>10-10 repeats). The results of other studies with nonASD samples also suggest a link between dysregulation of dopamine function, particularly over-activity, and Tourette syndrome (Singer et al. 2002; Yoon et al. 2007), and tic severity and DAT1 genotype (>10-10 repeats) (Rowe et al. 1998). Two, Hünnerkopf et al. (2007) found higher neuroticism scores in nonASD individuals with the Val/VAL BDNF genotype and who were not carriers of the 9-repeat DAT1 allele. Three, anxiety and tics appear to be highly interrelated (Coffey et al. 2000). In our ASD sample, the interaction term was significant (p = 0.02, ηp2 = 0.09) suggesting that the interactive effects of BDNF (Met66−) and DAT1 (10-10 repeat allele) risk genotypes are possibly synergistic, and the effect size was in the moderate range (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The interaction effect of BDNF (presence vs. absence of the Met allele, Met+ vs. Met−) and DAT1 (10-10 vs. non 10-10 repeat genotypes) polymorphism for teacher ratings of combined motor and vocal tic severity (M ± SEM)

Interpretation of study findings are subject to several qualifications. In accordance with much current support for intermediate phenotypes and dimensional strategies, particularly in ASD research (Abrahams and Geschwind 2008; Belmonte et al. 2004; Happé and Ronald 2008; Levy and Ebstein 2008), we used symptom severity scales to characterize component phenotypes (Szatmari et al. 2007). Therefore, obtained findings may not apply to categorical diagnoses. Because no statistical adjustments were made for multiple comparisons, this increased the probability of chance findings (Type 1 error). Therefore, all significant gene-behavior relations must be considered tentative and require replication in larger independent samples.

The size of the study sample may have limited our ability to detect more gene-behavior associations and restricted our ability to examine gene-gene interactions. For example, there were two marginally significant associations (p = 0.06, ηp2 = 0.06) between COMT variants and ASD severity that warrant consideration in future research: communication deficits (>Met158−, parent ratings) and perseverative behaviors (>Met158+, teacher ratings). In this regard, Karayiorgou et al. (1997) also reported more severe perseverative behaviors in Met158 homozygotes. Although puzzling, these source-specific associations are consistent with a deconstructive approach to the triad of ASD symptoms (Happé et al. 2006; Ronald et al. 2008). Although inadequate sample size is a common presumed source for inconsistent findings in the molecular biology, a meta-analysis of one of the most studied gene variants (5-HTTLPR) in ASD samples indicated that sample size was likely not the culprit (e.g., Huang and Santangelo 2008). Equally if not more likely possibilities are “replication drift” such as differences in type of informant (e.g., Ronald et al. 2008); assessment instrument (compare Lecavalier et al. 2009b; Snow et al. 2009); co-occurring symptomatology, which is highly problematic in ASD samples; conceptualization of the (endo)phenotype (e.g., Tordjman et al. 2001); and even genotyping errors (e.g., Yonan et al. 2006).

It is also possible that association signals may be weaker for the symptoms of syndromes such as anxiety, which are known to have lower heritability indices (particularly when based on point prevalence) and therefore evidence differentially greater susceptibility to environmental influences (Hettema et al. 2001) compared with other clinical phenotypes (e.g., ADHD, ASD). In other words, if the polygenic model (i.e., multiple genes, each with small effects) applies to co-occurring symptoms in ASD, then the failure to consider relevant environmental variables makes it more difficult to detect (and replicate) gene-behavior relations.

Our obtained findings may be spurious because genotype groups may have differed with regard to a variable confounded with gene activity. Moreover, a genetic subgroup(s) within the study sample may have been over-represented as having both the risk genotype and more severe anxiety symptoms, i.e., population stratification (see Cardon and Palmer 2003). The fact that all participants were Caucasian does not preclude this possibility. In addition, obtained gene-behavior associations may be better explained by (or consideration of) another gene variant(s) in linkage disequilibrium with the COMT or BDNF polymorphism (see Hettema et al. 2008).

Lastly, space constraints and both serious gaps and conflicting findings in the extant literature preclude the formulation of a compelling model for the possible role of these tentative gene variants in pathogenesis of co-occurring symptoms in this clinical phenotype. What can be said is that these particular genetic markers appear to be involved in brain development and on-going brain activity and are pleiotropic for the symptoms of commonly co-occurring psychiatric disorders, appear to interact differentially with environment variables as evidenced by source specificity, and are at some level likely to be interactive.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported, in part, by grants from the National Institutes of Health (GCRC grant No. M01RR1 0710), National Alliance for Autism Research, the Matt and Debra Cody Center for Autism and Developmental Disorders, and private donations. The authors wish to thank Dr. John Pomeroy for super-vising the clinical diagnoses and Dr. Joseph Schwartz for providing statistical consultation.

Footnotes

Kenneth D. Gadow: Shareholder in Checkmate Plus, publisher of the Child Symptom Inventory.

Contributor Information

Kenneth D. Gadow, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Science, State University of New York, Putnam Hall, South Campus, Stony Brook, NY 11794-8790, USA

Jasmin Roohi, Department of Genetics, Stony Brook University, Health Sciences Tower T8-053, Stony Brook, NY 11794-8088, USA, jasmin.roohi@hsc.stonybrook.edu.

Carla J. DeVincent, Department of Pediatrics, Cody Center for Autism and Developmental Disabilities, State University of New York, Putnam Hall, South Campus, Stony Brook, NY 11794-8788, USA, carla.devincent@sunysb.edu

Sarah Kirsch, Department of Pathology, State University of New York, HSC-T8, Room 053, Stony Brook, NY 11794-8088, USA, Karateandbb@aol.com.

Eli Hatchwell, Department of Pathology, State University of New York, HSC-T8, Room 053, Stony Brook, NY 11794-8088, USA, eli.hatchwell@stonybrook.edu.

References

- Abrahams BS, Geschwind DH. Advances in autism genetics: On the threshold of a new neurobiology. Nature Reviews. 2008;9:341–355. doi: 10.1038/nrg2346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen S. The hyper-systemizing, assertive mating theory of autism. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2006;30:865–872. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belmonte MK, Cook EH, Jr., Anderson GM, Rubenstein JLR, Greenough WT, Beckel-Mitchner A, et al. Autism as a disorder of neural information processing: Directions for research and targets for therapy. Molecular Psychiatry. 2004;9:646–663. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brieber S, Neufang S, Bruning N, Kamp-Becker I, Remschmidt H, Herpertz-Dahlmann B, et al. Structural brain abnormalities in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder and patients with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;48:1251–1258. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brune CW, Kim S-J, Leventhal BL, Lord C, Cook EH. 5-HTTLRP genotype-specific phenotype in children and adolescents with autism. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:2148–2156. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.12.2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardon LR, Palmer LJ. Population stratification and spurious allelic association. Lancet. 2003;361:598–604. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12520-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain B, Kasari C, Rotheram-Fuller E. Involvement or isolation? The social networks of children with autism in regular classrooms. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2007;37:230–242. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0164-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey BJ, Biederman J, Smoller JW, Geller DA, Sarin P, Schwartz S, et al. Anxiety disorders and tic severity in juveniles with Tourette’s disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:562–568. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200005000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen IL, Liu X, Schultz C, White BN, Jenkins EC, Brown WT, et al. Association of autism severity with a monoamine oxidase A functional polymorphism. Clinical Genetics. 2003;64:190–197. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2003.00115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comings DE, Wu S, Chiu C, Ring RH, Gade R, Ahn C, et al. Polygenetic inheritance of Tourette syndrome, stuttering, attention deficit hyperactivity, conduct, and oppositional defiant disorder. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics. 1996;67B:264–288. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19960531)67:3<264::AID-AJMG4>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drtilkova I, Sery O, Theiner P, Uhrova A, Zackova M, Balastikova B, et al. Clinical and molecular-genetic markers of ADHD in children. Neuroedocrinology Letters. 2008;29:320–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enoch M-A, White KV, Waheed J, Goldman D. Neurological and genetic distinctions between pure and comorbid anxiety disorders. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25:383–392. doi: 10.1002/da.20378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadow KD, DeVincent CJ. Clinical significance of tics and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children with pervasive developmental disorder. Journal of Child Neurology. 2005;20:481–488. doi: 10.1177/08830738050200060301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadow KD, DeVincent CJ, Pomeroy J. ADHD symptom subtypes in children with pervasive developmental disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2006;36:271–283. doi: 10.1007/s10803-005-0060-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadow KD, DeVincent CJ, Pomeroy J, Azizian A. Comparison of DSM-IV symptoms in elementary school-aged children with PDD versus clinic and community samples. Autism. 2005;9:392–415. doi: 10.1177/1362361305056079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadow KD, DeVincent C, Schneider J. Predictors of psychiatric symptoms in children with an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2008a;38:1710–1720. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0556-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadow KD, Roohi J, DeVincent CJ, Hatchwell E. Association of ADHD, tics, and anxiety with dopamine transporter (DAT1) genotype in autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008b;49:1331–1338. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01952.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadow KD, Schwartz J, DeVincent C, Strong G, Cuva S. Clinical utility of autism spectrum disorder scoring algorithms for the child symptom inventory. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2008c;38:419–427. doi: 10.1007/s10803-007-0408-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadow KD, Sprafkin J. Stony Brook child psychiatric checklist-3. Department of Psychiatry, State University of New York; Stony Brook: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Gadow KD, Sprafkin J. Child symptom inventory-4 screening and norms manual. Checkmate Plus; Stony Brook, NY: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gadow KD, Sprafkin J. The symptom inventories: An annotated bibliography [on-line] Checkmate plus; Stony Brook, NY: 2008. Available: www.checkmateplus.com. [Google Scholar]

- Gillott A, Furniss F, Walter A. Anxiety on high-functioning children with autism. Autism. 2001;5:277–286. doi: 10.1177/1362361301005003005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein S, Schwebach AJ. The comorbidity of pervasive developmental disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Results of a retrospective chart review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2004;34:329–339. doi: 10.1023/b:jadd.0000029554.46570.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grados MA, Mathews CA. Latent class analysis of gilles de la tourette syndrome using comorbidities: Clinical and genetic implications. Biological Psychiatry. 2008;64:119–225. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grice DE, Buxbaum JD. The genetic architecture of autism and related disorders. Clinical Neuroscience Research. 2006;6:161–168. [Google Scholar]

- Hall D, Dhilla A, Charalambous A, Gogos JA, Karayiorgou M. Sequence variants of the brain-derived neurotropic factor (BDNF) gene are strongly associated with obsessivecompulsive disorder. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2003;73:370–376. doi: 10.1086/377003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Happé F, Ronald A. The “fractionable autism triad”: A review of evidence from behavioural, genetic, cognitive and neural research. Neuropsychology Review. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s11065-008-9076-8. doi: 10.1007/s11065-008-9076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Happé F, Ronald A, Plomin R. Time to give up on a single explanation for autism. Nature Neuroscience. 2006;9:1218–1220. doi: 10.1038/nn1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettema JM. What is the genetic relationship between anxiety and depression? American Journal of Medical Genetics: Part C Seminars in Medical Genetics. 2008;148C:140–146. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettema JM, An S-S, Bukszar J, ven den Oord EJCG, Neale MC, Kendler KS, et al. Catechol-O-methyltransferase contributes to genetic susceptibility shared among anxiety spectrum phenotypes. Biological Psychiatry. 2008;64:302–310. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettema JM, Neale MC, Kendler KS. A review and meta-analysis of the genetic epidemiology of anxiety disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:1568–1578. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.10.1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirshfeld DR, Micco JA, Simoes NA, Henin A. High risk studies and developmental antecedents of anxiety disorders. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics. 2008;148C:99–117. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Four factor index of social status. Department of Sociology, Yale University; New Haven, CT: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Hovatta I, Barlow C. Molecular genetics of anxiety in mice and men. Annals of Medicine. 2008;40:92–109. doi: 10.1080/07853890701747096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CH, Santangelo SL. Autism and serotonin transporter gene polymorphisms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B Neuro-psychiatric Genetics. 2008;147B:903–913. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hünnerkopf R, Strobel A, Gutknecht L, Brocke B, Lesch KP. Interaction between BDNF Val66Met and dopamine transporter gene variation influences anxiety-related traits. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:2552–2560. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Xu K, Hoberman J, et al. BDNF variation in mood disorders: A novel functional promoter polymorphism and Val66Met are associated with anxiety but have opposing effects. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:1353–1361. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanner L. Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nervous Child. 1943;2:217–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karayiorgou M, Altemus M, Galke BL, et al. Genotype determining low catechol-O-methyltransferase activity as a risk factor for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 1997;94:4572–4575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecavalier L, Gadow KD, DeVincent CJ, Edwards MC. Validation of DSM-IV model of psychiatric syndromes in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2009a;39:278–289. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0622-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecavalier L, Gadow KD, DeVincent CJ, Houts C, Edwards MC. Deconstructing the PDD clinical phenotype: Internal validity of the DSM-IV. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02104.x. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Laurin N, Crosbie J, et al. Association study of the brain-derived neurotropic factor (BDNF) gene in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics. 2007;114B:976–981. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy Y, Ebstein RP. Research review: Crossing syndrome boundaries in the search for brain endophenotypes. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008 doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01986.x. doi: 10.111/j.1469-7610.2008.01986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin P-I, Vance JM, Pericak-Vance MA, Martin ER. No gene is an island: The flip-flop phenomenon. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2007;80:531–538. doi: 10.1086/512133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Risi S, Lambrecht L, Cook EH, Jr, Leventhal BL, DiLavore PC, et al. The autism diagnostic observation schedule-generic: A standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2000;30:205–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Lindenberg A, Weinberger DR. Intermediate phenotypes and genetic mechanisms of psychiatric disorders. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2006;7:818–827. doi: 10.1038/nrn1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura K, et al. Genetic analyses of the brain-derived neurotropic factor (BDNF) gene in autism. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2007;356:200–206. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.02.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perneger TV. What’s wrong with Bonferroni adjustments. British Medical Journal. 1998;316:1236–1238. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7139.1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronald A, Happé F, Plomin R. A twin study investigating the genetic and environmental aetiologies of parent, teacher and child ratings of autistic-like traits and their overlap. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s00787-008-0689-5. doi: 10.1007/s00787-008-0689-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roohi J, DeVincent CJ, Hatchwell E, Gadow KD. Association of a monoamine oxidase-A gene promoter polymorphism with ADHD and anxiety in boys with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2009;39:67–74. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0600-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman K. No adjustments are needed for multiple comparisons. Epidemiology. 1990;1:43–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe DC, Stever C, Gard JMC, Cleveland HH, Sanders ML, Abramowitz A, et al. The relation of the dopamine transporter gene (DAT1) to symptoms of internalizing disorders in children. Behavior Genetics. 1998;28:215–225. doi: 10.1023/a:1021427314941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Couteur A, Lord C. Autism diagnostic interview-revised. Western Psychological Services; Los Angeles, CA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rzhetsky A, Wajngurt D, Park N, Zheng T. Probing genetic overlap among complex human phenotypes. PNAS. 2007;104:11694–11699. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704820104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer HS, Szymanski S, Guiliano J, Yokoi F, Dogan AS, Brasic JR, et al. Elevated intrasynaptic dopamine release in Tourette syndrome measured by PET. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:1329–1336. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.8.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinzig J, Morsch D, Bruning N, Schmidt MH, Lehmkuhl G. Inhibition, flexibility, working memory and planning in autism spectrum disorders with and without comorbid ADHD-symptoms. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health. 2008;2(1):4. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-2-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smalley SL, Kustanovich V, Minassian SL, Stone JL, Ogdie MN, McGough JJ, et al. Genetic linkage of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder on chromosome 16p13, in a region implicated in autism. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2002;71:959–963. doi: 10.1086/342732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smalley SL, McCracken J, Tanguay P. Autism, affective disorders, and social phobia. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 1995;60:19–26. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320600105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smoller JW, Gardner-Schuster E, Misiaszek M. Genetics of anxiety: Would the genome recognize the DSM? Depression and Anxiety. 2008;25:368–377. doi: 10.1002/da.20492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snow AV, Lecavalier L, Houts C. Structure of the autism diagnostic interview-revised: Diagnostic and phenotypic implications. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50:734–742. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.02018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukhodolsky DG, Scahill L, Gadow KD, Eugene AL, Aman MG, McDougle CJ, et al. Parent-rated anxiety symptoms in children with pervasive developmental disorders: Frequency and association with core autism symptoms and cognitive functioning. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:117–128. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9165-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sverd J. Psychiatric disorders in individuals with pervasive developmental disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 2003;9:111–127. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200303000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szatmari P, Maziade M, Zwaigenbaum L, Merette C, Roy M-A, Joober R, et al. Informative phenotypes for genetic studies of psychiatric disorders. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics. 2007;144B:581–588. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thapar A, Langley K, O’Donovan M, Owen M. Refining the attention deficit hyperactivity disorder phenotype for molecular genetic studies. Molecular Psychiatry. 2006;11:714–720. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tordjman S, Gutknecht L, Carlier M, Spitz E, Antoine C, Slama F, et al. Role of the serotonin transporter gene in the behavioral expression of autism. Molecular Psychiatry. 2001;6:434–439. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turri MG, Datta SR, DeFries J, Henderson ND, Flint J. QTL analysis identifies multiple behavioral dimensions in etiological tests of anxiety in laboratory mice. Current Biology. 2001;11:725–734. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00206-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisbrot DM, Gadow KD, DeVincent CJ, Pomeroy J. The presentation of anxiety in children with pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2005;15:477–496. doi: 10.1089/cap.2005.15.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang MS, Gill M. A review of gene linkage, association and expression studies in autism and an assessment of convergent evidence. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience. 2007;25:69–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonan AL, Palmer AA, Gilliam TC. Hardy-Weinberg disequilibrium identified genotyping error of the serotonin transporter (SLC6A4) promoter polymorphism. Psychiatric Genetics. 2006;16:31–34. doi: 10.1097/01.ypg.0000174393.79883.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon DY, Rippel CA, Kobets AJ, Morris CM, Lee JE, Williams PN, et al. Dopaminergic polymorphisms in Tourette syndrome: Association with DAT gene (SLC6A3) American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics. 2007;114B:605–610. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Myers AN, Vandersteen JG, Wang L, Wittwer CT. Closed-tube genotyping with unlabeled oligonucleotide probes and a saturating DNA dye. Clinical Chemistry. 2004;50:328–335. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2004.034322. Epub 27 May 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]