Abstract

Objective: The purpose of this systematic review was to examine the literature for associations between spiritual well-being and quality of life (QOL) among adults diagnosed with cancer.

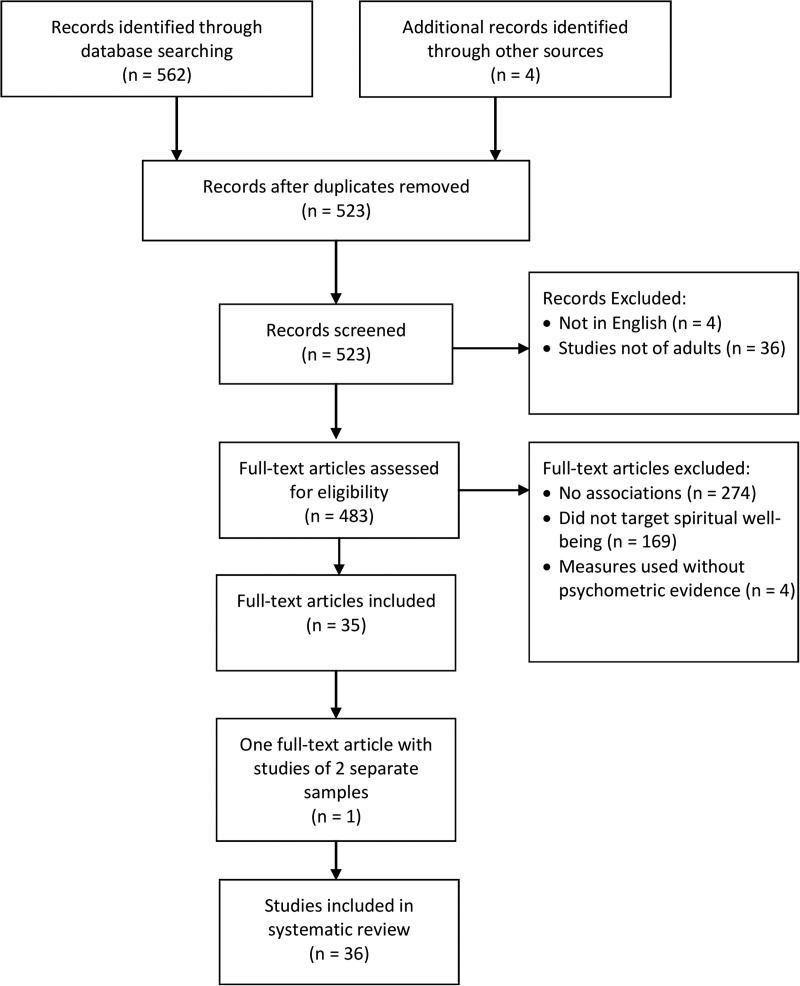

Methods: A systematic literature search was conducted in the PubMed and CINAHL databases on descriptive correlational studies that provided bivariate correlations or multivariate associations between spiritual well-being and QOL. A total of 566 citations were identified; 36 studies were included in the final review. Thirty-two studies were cross-sectional and four longitudinal; 27 were from the United States. Sample size ranged from 44 to 8805 patients.

Results: A majority of studies reported a positive association (ranges from 0.36 to 0.70) between overall spiritual well-being and QOL, which was not equal among physical, social, emotional, and functional well-being. The 16 studies that examined the Meaning/Peace factor and its association with QOL reported a positive association for overall QOL (ranges from 0.49 to 0.70) and for physical (ranges from 0.25 to 0.28) and mental health (ranges from 0.55 to 0.73), and remained significant after controlling for demographic and clinical variables. The Faith factor was not consistently associated with QOL.

Conclusions: This review found consistent independent associations between spiritual well-being and QOL at the scale and factor (Meaning/Peace) levels, lending support for integrating Meaning/Peace constituents into assessment of QOL outcomes among people with cancer; more research is needed to verify our findings. The number of studies conducted on spiritual well-being and the attention to its importance globally emphasizes its importance in enhancing patients' QOL in cancer care.

Introduction

Interest in spirituality, religion, and spiritual well-being (SpWB) for patients with cancer has grown over the past few decades. But there remains a lack of clarity about to what the terms refers. “Spirituality” has historically referred to religious beliefs and practices.1 The terms “religion” and “religiosity” are associated with personal orthodoxy to a specific religious tradition and practices that grow out of that orthodoxy, such as worship attendance.2 However, the Pew Research Center's 2012 survey on religion and public life found that 37% of the people who identified themselves as unaffiliated with any religion said they still considered themselves spiritual.3 To these “spiritual but nones” the term “spirituality” has a broader meaning than religious-specific beliefs and practices. So in modern usage the term has a broad meaning.4–5 The word “faith” is often used interchangeably with “religion,” referring to the whole of a tradition's belief system. But it can also mean trust or confidence in something other than a religious tradition, encompassing one's orientation toward oneself, other people, and the universe, and reflects the dynamic personal element in human piety.6

In the scientific literature the term “SpWB” is used to indicate a measurable domain of quality of life (QOL).7–8 Viewed as a multifaceted construct, SpWB usually refers to a sense of meaning or purpose in life, inner peace and harmony, and the strength and comfort drawn from faith.9 But researchers have not been able to agree upon the makeup of the construct of SpWB, which varies depending on the scales used to measure it. SpWB has been measured over two dimensions.7,10 Recently, it has been argued that Meaning/Peace be divided into two separate factors, Meaning and Peace, and thus the measure SpWB would be viewed as comprising the three factors of Meaning, Peace, and Faith.11

With the lack of univocity of terms, studies on spirituality are largely mixed with those examining the role of religiosity in cancer adjustment, the effect of spiritual/religious coping on QOL, and the association between SpWB and QOL. We reviewed the literature on the association between SpWB and QOL among people diagnosed with cancer to answer three questions related to the issue of what is measured when studying SpWB in the context of QOL: (1) Is there an association between SpWB and QOL at the questionnaire or scale level? (2) Are there associations between the factors of SpWB and QOL? If so, (3) do these associations remain significant among other domains of QOL?

Methods

A literature search was conducted in the PubMed and CINAHL databases on studies published between January 1, 1960 and September 29, 2013, using the following medical subject headings (MeSH) or CINAHL exact subject headings: “spirituality” or “existentialism,” AND “quality of life/psychological,” “emotions,” “health,” or “adaptation/psychological,” AND “neoplasms.” In addition, titles and abstracts were searched in PubMed for “spirituality” or “spiritual well-being” to ensure a comprehensive retrieval of citations for studies not caught by the MeSH search for “spirituality.”

We distinguished between SpWB measures and measures of other aspects of spirituality, such as strength of spiritual beliefs, to make the examined relationship homogenous, and included only the descriptive correlational studies that provided bivariate correlations or multivariate associations between SpWB and QOL. We searched the references of included articles for studies that fit criteria. Studies were excluded if they: (1) did not examine the association between SpWB and QOL; (2) targeted religious coping, belief, or practice, rather than SpWB; (3) studied caregivers, children, or adolescent patients; (4) did not use validated instruments to measure SpWB or QOL; (5) were not in English; (6) were not published in peer-reviewed journals; and (7) were duplicative across databases.

We followed the criteria for reporting systematic reviews of intervention and observation studies,12–13 and included in our review study design, sample characteristics, results of correlations between SpWB and QOL, and when multivariate analyses were used, the significance and direction of the relationship and the variables being controlled for. Authors were contacted for missing information.

Results

We have organized the results into three sections: search results, sample and methodological characteristics of included studies, and findings of reviewed studies on the association between SpWB and QOL.

Search results

Five hundred sixty-two records were identified through searching databases (Fig. 1). Five hundred thirty-four were excluded because they: did not include analysis of correlations between SpWB and QOL (n=274); targeted religious coping, belief, or practice rather than SpWB (n=169); included populations other than only adult cancer patients (n=38); used measures that lacked psychometric evidence (n=4); were not written in the English language (n=6); or were duplicative across databases (n=43). Four studies were added from hand-searching references of included full-text articles. A total of 35 full-text articles, which are marked by an asterisk in the reference list and described in Table 1, were included in the final review. Peterman and colleagues10 conducted a psychometric evaluation study from the same sample as Brady and colleagues,14 however with different timing and outcome variables; we counted these two reports separately. Salsman and colleagues15 reported studies based on two different samples of colorectal cancer patients; we reviewed each sample as a different study. Thus the final number of studies included for review was 36.

FIG. 1.

Flow diagram of search results.

Table 1.

Summary of Full-Text Articles Included in Systematic Review

| Author (year) Origin [reference] | Sample | Origin | Measures | Statistics | Major findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohen (1996) Canada [28] | N=247; patients with no evidence of disease (n=126), with meta or local cancer (n=101); median time since diagnosis: 28.5 months | Canada |

MQOL (each domain) SIS SA-QOL |

Spearman correlation Multiple regression |

1. Existential well-being strongly correlated with SIS (0.57), and moderately related to SA-QLI (0.48) as well as physical well-being item (0.46) at p<0.0001 level. 2. The association between existential well-being and overall QOL was “more heavily weighted” on participants with local or metastatic cancer, even after controlling for physical well-being, physical symptoms, psychological symptoms, and existential well-being contributed greatest to SIS. |

| Brady (1999) U.S. [14] | N=1610, time since diagnosis: 11.8 months (Med), cancer 83%; race/ethnicity: predominantly minority (Latino 44.5%, African 31.1%, European 24.4%) | U.S. |

FACT-G FACIT-Sp-12 |

1. Pearson correlation2. General linear regression3. Stepwise logistic regression4. Hierarchical logistic regression5. Chi-square | 1. FACIT-Sp-12 positively correlated with total FACT-G (0.58) and Gf-7 (0.48), with Meaning/Peace (FACT-G: 0.62; Gf-7: 0.49) correlated much stronger than Faith (0.35, 0.36).2. FACIT-Sp-12 and two subscales remained independent predictors of total FACT-G controlling for demographic and clinical characteristics.3. Meaning/Peace was the best predictor of Gf-7; Faith came before social/family well-being.4. FACIT-Sp-12 and two subscales remained unique predictors of Gf-7 controlling QOL domains. |

| Cotton (1999) U.S. [34] | N=142, invasive breast cancer; time since diagnosis: 14.49 months (mean) | U.S. | FACIT-B Self-rated health FACIT-Sp-12 |

1. Spearman correlation2. Hierarchical regression |

1. FACIT-Sp-12 was moderately positively correlated with FACIT-B (0.48); the association between FACIT-Sp-12 and self-rated health was not significant (-0.02).2. FACIT-Sp-12 uniquely contributed to FACIT-B, controlling for demographic variables, self-rated health, coping style (measured by the Mini-Mental Adjustment to Cancer) and the Principles of Living survey |

| Johnson (2001)U.S. [46] | N=85, 49% for chronic leukemia and 51% for acute leukemia. All received allogenic transplants; time since treatment: 6.5–11 years | U.S. | LAP-R (PMI) SF-36 GSI PCL |

Multiple linear regression | Controlling for PCS, gender, and other clinical variables, global meaning was associated with BMT-related distress, global distress, and its two subscales of depression and anxiety, as well as MCS and emotional role functioning, mental health, vitality, but not social functioning. |

| Peterman (2002) U.S. [10] | N=1617, time since diagnosis: 29 months (Med), cancer 83%; race/ethnicity: predominantly minority (Latino 44.4%, African 31.1%, European 24.5%) | U.S. |

FACT-G (total score) FACIT-Sp-12 (total score; 2-factor) POMS (total score) |

Spearman correlation | 1. Meaning/Peace (EWB: 0.57; FWB: 0.54) as well as the total FACIT-Sp-12 (EWB: 0.55; FWB: 0.51) strongly correlated with EWB, FWB, weakly or moderately correlated with PWB (M/P: 0.31; Sp: 0.25) and SWB (M/P: 0.46; Sp: 0.44). Faith positively correlated with EWB (0.35), FWB (0.31) and SWB (0.28), not associated with PWB.2. FACIT-Sp-12 negatively correlated with POMS (-0.54), with Meaning/Peace (-0.60) correlated much stronger than Faith (-0.30). |

| Tate (2002) U.S. [44] | N=72, recurrent cancer patients, breast or prostate cancer. Time since diagnosis: 6 years for breast cancer patients, 4 years for prostate cancer patients | U.S. |

FACT-G-R (v.2) FACIT-Sp-12-R FLIC SF-36 SWLS |

Zero-order correlation Hierarchical linear regression |

1. Spiritual well-being was strongly correlated with QOL on the FLIC (0.55), and moderately related with life satisfaction on the SWLS (0.39).2. Controlling for age, education, emotional well-being, social function (on the SF-36), and functional well-being, FACIT-Sp-13 was not related to either QOL or life satisfaction for cancer patients in this example. |

| Laubmeier (2004) U.S. [43] | N=95; time since diagnosis: within 5 years | U.S. | SWBS FACT-G GSI |

Hierarchical linear regression with interaction Stepwise linear regression |

1. Controlling for PLT, spiritual well-being significantly contributed to anxiety/depression as well as QOL, whereas the association with GSI approached significance. The interaction between PLT and spiritual well-being was not significant.2. EWB entered before RWB in stepwise regressions predicting anxiety/depression, GSI, and QOL, indicating EWB was a stronger contributor than RWB. Although RWB accounted for significant proportions of variance of anxiety/depression and GSI, it didn't uniquely contribute to QOL. |

| Noguchi (2004) Japan [24] | N=306, performance status: ECOG ≤1 accounted for 88.9%; religion: not indicated | Japan |

FACIT-Sp-12 (total score, 2-factor) FACT-G |

Pearson correlation | FACIT-Sp-12 and two subscales were positively correlated with FACT-G domains. |

| Voogt (2005) Netherlands [27] | N=105, advanced cancer; time since diagnosis: 21.6 months; religious beliefs: 40% none | Netherlands | PANAS FACIT-Sp-12 |

1. Pearson correlation 2. Multiple linear regression |

1. Meaning/Peace (0.43) and Faith (0.29) both positively correlated with positive affect; only Meaning/Peace (-0.39) was significantly correlated with negative affect.2. Controlling for demographic, treatment, other domains of QOL (EORTC-QLQ-C30), and coping, Meaning/Peace remained significant predictors for both positive and negative affect, whereas the associations of Faith were not significant. |

| Kristeller (2005) U.S. [53] | N=118; time since diagnosis: 52% diagnosed within 2 years; treatment: 54% in active treatment | U.S. |

FACT-G (total, EWB, FWB) FACIT-Sp-12 |

Pearson correlation | FACIT-Sp at baseline was strongly related to emotional (0.58), functional well-being (0.58), and total FACT-G (r=0.57), and moderately related to depressed mood (-0.45). |

| Daugherty (2005)U.S. [54] | N=162, cancer patients volunteered to Phase I trial | U.S. | FACIT-Sp-12 FACT-G (v.3) |

Spearman correlation | FACIT-Sp-12 was positively correlated with FACT-G total (0.36) as well as all the subscales (SWB: 0.24; RWB: 0.25; EWB: 0.39; FWB: 0.38) except the physical well-being (0.14). |

| Krupski (2006) U.S. [30] | N=287, low-income prostate cancer patients; localized disease (59.2%), race/ethnicity: Hispanic: 51.2%, black: 18.1%, white: 23.0%; education: 85.7% high school or less | U.S. | FACIT-Sp-12 SF-12 MHI-5 PCI-SF SDS |

Multiple linear regression | Spiritual well-being as well as its Peace/Meaning subscale was positively associated with PCS, MCS, MHI-5, SDS, and PCI-SF controlling for demographic and medical variables; Faith did not contribute significantly to dependent variables in multivariate context. |

| Kruse (2007) U.S. [41] | N=60, enrolled in hospice; cancer 55% | U.S. |

FACIT-Sp-12(2-factor) Visual Analogue physical health |

Pearson Correlation | There was no significant relationship between FACIT-Sp-12 or its two factors with physical health. |

| Johnson (2007) U.S. [16] | N=103, advanced cancer receiving radiation therapy; female: 36%; time since diagnosis: within past 12 months; treatment: prior surgery 99%, currently receiving chemo 61% | U.S. | 5-item LASAs Single item overall spiritual well-being | Spearman correlation | 1. Single item overall spiritual well-being was strongly associated with global QOL as well as the other 4 QOL domains (on the 5-item LASAs) at all four time points: global QOL (r=0.59-0.70), mental well-being (r=0.63-0.75), physical well-being (r=0.50-0.64), emotional well-being (r=0.64-0.76) and social well-being (r=0.63-0.75). [note: 81 participants completed all time points] (reviewers' notes: no psychometric validation study could be identified supporting the selected domains of QOL except the global QOL, therefore only global QOL result was used for subsequent analysis.) |

| Edmondson (2008) U.S. [45] | N=237, time since primary treatment: 55% within 1 year, 11% above 4 years (i.e., differing lengths of survivorship) | U.S. |

FACIT-Sp-12 (2-factor) SF-12 |

1. Pearson correlation 2. Hierarchical linear regression |

1. Meaning/Peace was positively strongly related to MCS (0.59) and weakly correlated with PCS (0.26); Faith was only weakly positively associated with MCS (0.17).2. Controlling for Meaning/Peace, the effect of Faith on MCS was reversed (p<0.05), greater Faith was related to worse mental QOL when degree of Meaning/Peace was held constant.3. Meaning/Peace remained significant predictor of both MCS and PCS controlling for Faith, optimism (measured with the Life Orientation Test-Revised, LOT-R), and relevant sociodemographic and clinical variables. |

| Canada (2008) U.S. [11] | N=240, all female; time since diagnosis: 10 years | U.S. |

FACIT-Sp-12 (total score; 2-factor; 3-factor) SF-12 (2-factor) BSI-18 (total score) |

1. Pearson correlation 2. Partial correlation |

1. FACIT-Sp-12 strongly positively correlated with PCS (0.50) and weakly associated with MCS (0.14).2. Meaning/Peace controlling for Faith strongly correlated with MCS (0.63) and weakly associated with PCS (0.22); Faith controlling for Meaning/Peace negatively associated with MCS (-0.17), not associated with PCS.3. After controlling for the other spiritual well-being factors, Peace was only related to MCS (0.53); Meaning was related to both MCS (0.17) and PCS (0.18).4. FACIT-Sp-12 strongly negatively correlated with BSI-18 (-0.50); controlling for other factor(s), Meaning/Peace (-0.63), Peace (.-0.45), and Meaning (-0.29) negatively associated with BSI-18, whereas Faith positively associated with BSI-18 (0.22). |

| Prince-Paul (2008) U.S. [55] | N=50, convenience sample; setting: home (hospice program) | U.S. |

JAREL spiritual well-being scale FACT-G (SWB only) QUAL-E (single item) |

Pearson correlation | 1. JAREL (spiritual well-being) was strongly positively correlated with the single-item QUAL-E (0.59), and moderately related with social well-being (of FACT-G) (0.42). |

| Whitford (2008) Australia [20] | N=449; country of origin: 71.0% from Australia/New Zealand; treatment status: 25% had surgery, 44% receiving radiation, 32% on chemo; religion: none-religious 17%; unknown 16% | Australia |

FACT-G(total score, each domain, Gf-7, Gf-3) FACIT-Sp-12(total score; 2-factor) |

1. Pearson correlation2. Hierarchical linear regression3. Chi-square | 1. FACIT-Sp-12 and two subscales were moderately and positively associated with total FACT-G (M/P: 0.69, Faith: 0.25) as well as PWB (M/P: 0.37, Faith: 0.01 ns), SWB (M/P: 0.40, Faith: 0.27), EWB (M/P: 0.53, Faith: 0.22), and FWB (M/P: 0.67, Faith: 0.20) (except between Faith and physical well-being); Meaning/Peace correlated stronger than Faith subscale.2. FACIT-Sp-12 uniquely contributed to Gf-7 controlling for QOL domains; physical well-being had the greatest contribution |

| Sun (2008) U.S. [17] | N=45 (22 hepatocellular carcinoma, 23 pancreatic cancer); race/ethnicity: Caucasian (51%), Asian (22%), Hispanic (18%) | U.S. | FACIT-Sp-12 FACT-Hep |

Pearson correlation | Correlations between FACIT-Sp-12 and symptom score (FACT-Hep subscale) at baseline, 1-month, 2-months, and 3-months decreased over time: 0.54, 0.35, 0.31, and 0.27. |

| Zavala (2009) U.S. [31] | N=86, low-income metastatic prostate cancer patients; race/ethnicity: Hispanic: 62%, black: 10%, white: 20%; time since biopsy: 71% <1 year; education: 87% high school or less | U.S. | FACIT-Sp-12 SF-12 |

t test Multiple linear regression with interaction |

1. Dichotomized spiritual well-being (lowest quartile versus upper 75% FACIT-Sp-12) significantly associated with PCS, MCS, and one-item pain (from SF-12).2. Controlling for demographic and comorbidity variables, dichotomized FACIT-Sp-12 was not associated with PCS, MCS, or pain.3. When examined simultaneously, Meaning/Peace remained significant predictor of PCS, MCS, as well as pain, whereas Faith did not contribute to any outcome (main effect).4. Significant interaction revealed between Meaning/Peace and Faith in association with PCS and pain. Higher Meaning/Peace was associated with higher PCS and less pain regardless of Faith and particularly when Faith was low; in contrast, higher Faith was associated with poorer PCS and more pain in the context of low Meaning/Peace. |

| Purnell (2009) U.S. [35] | N=130, early-stage breast cancer (stage I, II), all had surgery; convenience, consecutive; time since treatment: 24 months after surgery | U.S. |

SF-36 (MCS) FACIT-Sp-12 (2-factor) IES |

Pearson correlation Hierarchical linear regression | 1. FACIT-Sp-12 (-0.47) negatively moderately associated with IES, with Meaning/Peace (-0.48) correlated much stronger than Faith (-0.29).2. FACIT-Sp-12 (0.67) positively strongly associated with MCS, with Meaning/Peace (0.73) correlated much stronger than Faith (0.34).3. Meaning/peace remained significant predictor of the MCS and IES, whereas Faith was not significant when examined simultaneously with Meaning/Peace.4. Controlling for relative demographic or clinical variables, FACIT-Sp-12 remained significant predictor of both MCS and IES. |

| Mazanec (2010) U.S. [36] | N=163, newly diagnosed; time since diagnosis: within 6 months, mean 87 days; stage: 64% III, IV; performance status: 80% highly functioning (ECOG 0 or 1); current treatment: chemotherapy 87%, radiation 28% | U.S. | FACIT-Sp-12 FACT-G |

Hierarchical linear regression | Controlling for age, ECOG, POMS-SF anxiety and depression subscales as well as optimism (LOT-R), spiritual well-being significantly contributed to overall QOL and social, emotional, as well as functional well-being, not physical well-being. |

| Friedman (2010) U.S. [32] | N=108, breast cancer, stage I or II; race/ethnicity: Hispanic: 44%, black: 41%, white: 10%; time since diagnosis: 21 months | U.S. | FACIT-Sp-12 FACIT-B POMS-SF |

Pearson correlation Multiple linear regression |

1. FACIT-Sp-12 strongly correlated with both FACIT-B (0.63) and POMS-SF (-0.55).2. Controlling for self-blame, self-forgiveness, and relevant demographic, spiritual well-being remained significant predictor for both FACIT-B and POMS-SF. |

| Murphy (2010) U.S. [29] | N=8805; time since diagnosis: 2 years 35%, 5 years 36%; 10 years 39% | U.S. |

FACIT-Sp-12 (total score, 2-factor, 3-factor) SF-36 |

1. Pearson correlation 2. Hierarchical regression |

1. FACIT-Sp-12 (MCS: 0.57; PCS: 0.21), Meaning/Peace (MCS: 0.67; PCS: 0.28), Meaning (MCS: 0.55; PCS: 0.27) and Peace (MCS: 0.66; PCS: 0.25) were strongly positively associated with MCS, weakly associated with PCS. Faith was weakly positively associated with MCS (0.25) only.2. Holding the other factor constant, Peace and Meaning uniquely contributed to MCS and PCS, with Peace accounted for notably more to MCS than Meaning. |

| Salsman (2011) U.S. [15] | Study 1: N=258, colorectal cancer; predominantly minority: Latino 56%, African American 33%, European American 11%; time since diagnosis: 17 months (mean); Study 2: N=568; colorectal cancer; time since diagnosis: 19 months (mean) | U.S. |

FACIT-Sp-12 (2-factor) FACT-C (TOI-R, EWB, SFWB) |

Multiple linear regression with interaction | 1. Separately examined, Meaning/Peace and Faith were both positively associated with TOI-R, EWB, and SFWB in both samples, and sample 2 revealed a more robust relationship; simultaneously examined, Meaning/Peace remained significantly associated in both samples. The above regression has adjusted for demographic and clinical variables.2. Meaning/Peace was positively associated with TOI-R, EWB, and SFWB regardless of POMS levels in both samples. |

| Mazzotti (2011) Italy [26] | N=152; time since diagnosis: less than 6 months for 45%; the rest had metastasis and had received palliative treatment | Italy | FACIT-Sp-12 FACT-G HADS |

Spearman correlation Multivariate logistic regression |

1. Meaning/Peace was moderately and positively correlated with EWB (0.48), and negatively with HADS-D (-0.41), but not with HADS-A. (reviewer note: not clear about Faith)2. Using cut-off score of 50, higher Meaning/Peace was associated with lower levels of HADS-A, HADS-D (both using cut-off score of 8), as well as higher EWB (using cut-off of 50); similarly using cut-off score of 50, higher Faith was associated with higher FWB and SWB (both using cut-off of 50).3. Adjusting for demographic and clinical variables as well as positive coping, HADS-A (≤8, OR 4.5, 95%CI 1.4-14.0) remained significantly associated with Meaning/Peace (>50).4. Adjusting for demographic, clinical variables, as well as coping, both FWB (>50, OR 2.5, 95% CI 1.3-4.9) and SWB (>50, OR 3.3, 95% CI 0.9-11.7) remained significantly associated with Faith (>50). |

| Kim (2011) U.S. [42] | N=316; time since diagnosis: 2.2 years (mean) | U.S. | SF-36 FACIT-Sp-12 |

Structural equation modeling | Using 1-factor, 2-factor, and 3-factor models, spiritual well-being overall, Meaning/Peace, Meaning, and Peace factor contributed to both MCS and PCS, controlling for individual's age, stage of cancer, as well as caregiver's spiritual well-being; Faith did not contribute to either MCS or PCS. |

| Smith (2011) U.S. [18] | N=44, metastatic breast cancer patients | U.S. | FACIT-Sp-12 FACT-G |

Spearman correlation Multiple linear regression |

Change of FACIT-Sp-12 as well as its Meaning/Peace subscale from baseline to 6 months was positively correlated with change of EWB, even after adjusting for baseline outcome scores and patient characteristics. |

| Lazenby (2012) Jordan [23] | N=159; religion: Muslim cancer patients; mean age: 46 years | Jordan |

FACIT-Sp-12 FACT-G (33 items) |

Spearman correlation | For stage IV subgroup, FACIT-Sp-12 was positively correlated with SWB (0.54) and FWB (0.57), and negatively correlated with PWB (-0.37) and EWB (-0.50). Similar patterns were seen for stage III patients and for male patients. FACIT-Sp-12 in female patients showed similar positive relationships with SWB and FWB; however, the associations with PWB or EWB were not significant. |

| Whitford (2012) Australia [21] | N=999, newly diagnosed; country of Origin: 69.1% from Australia/New Zealand; religion: none-religious 30% | Australia |

FACT-G (total score, each domain, Gf-7, Gf-3) FACIT-Sp-12 (total score, 3-factor) |

1. Pearson correlation2. Hierarchical linear regression3. Chi-square | 1. Peace was more correlated with emotional well-being, whereas Meaning was more correlated with social well-being. Three subscales of the FACIT-Sp-12 had positive small-to-moderate associations with total FACT-G, functional, social, as well as emotional well-being.2. FACIT-Sp-12 uniquely contributed to Gf-7 controlling for QOL domains; Peace contributed most after further controlling for the other two factors of the FACIT-Sp-12; Faith was not significantly contributing to QOL in the multivariate context. |

| Samuelson (2012) U.S. [19] | N=406, enrolled at the time of beginning radiation therapy | U.S. | FACT-G FACIT-Sp-12 |

Pearson correlation Multiple linear regression |

Change of the FACT-G and FACIT-Sp-12 from treatment initiation to discharge was moderately correlated (0.40), remaining after controlling for gender, race, marital/partnered status, zip code, employment or insurance status, primary tumor location, and purpose of treatment (palliative versus definitive). |

| Matthews (2012) U.S. [33] | N=248 African American+244 white; site: breast, prostate, or colorectal; time since diagnosis: within 3 years | U.S. | SF-36 FACIT-Sp-12 |

Multiple linear regression | Controlling for demographic, clinical factors as well as other psychosocial variables, FACIT-Sp-12 were significantly related to MCS, but not to PCS. The interaction between race and spiritual well-being in the relationship with either MCS or PCS was not significant. |

| Lazenby (2013) Jordan [22] | N=205; religion: predominantly Muslim (73%) | Jordan |

FACT-Sp (each dimension, Gf-7) FACIT-Sp-12 (total score, 3-factor) |

1. Pearson correlation2. Hierarchical linear regression | 1. FACIT-Sp-12 was positively correlated with social and functional well-being, but negatively related to emotional well-being.2. Both Peace and Faith were positively associated with social and functional well-being, and negatively associated with emotional well-being; Peace was negatively correlated with physical well-being; Meaning was positively correlated with social and functional well-being only.3. FACIT-Sp-12 and three subscales uniquely contributed Gf-7 controlling QOL domains, of which Peace accounted for the largest proportion. |

| Jafari (2013) Iran [25] | N=153; religion: Muslim cancer patients; mean age: 47 years | Iran |

FACIT-Sp-12 (total score, 3-factor) FACT-G |

Pearson correlation | Overall spiritual well-being as well as Peace, Meaning, and Faith factors (via confirmatory factor analysis) was positively correlated with physical, social/family, emotional, as well as functional domain of QOL, except for the association between Faith and physical well-being, which was insignificant. |

| Bai (2014) U.S. [37] | N=118; median time since diagnosis: 128.5 days | U.S. |

FACIT-Sp-12 (2-factor, 3-factor) FACT-G |

Spearman correlation Partial correlation |

1. Peace (0.63) and Meaning (0.70) positively correlated with overall QOL; Faith did not relate to overall QOL significantly.2. Controlling for the other two factors of spiritual well-being, both Peace (0.32) and Meaning (0.41) positively related to overall QOL. Peace was also positively associated with emotional (0.51) and functional well-being (0.28), whereas Meaning was associated with physical (0.35), social/family (0.32), and functional well-being (0.41) in partial correlations; Faith was only negatively related to emotional well-being (-0.31) when controlling for Meaning and Peace.3. Using original 2-factor model, Meaning/Peace positively related with overall QOL as well as all the QOL domains controlling for Faith, whereas Faith did not associate with either overall or subdomains of QOL when controlling for Meaning/Peace. (Peace, Meaning, and Faith factors were identified using common factor analyses.) |

BMT, Bone Marrow Transplantation; BSI-18, the Brief Symptom Inventory 18; BSI-D, Brief Symptom Inventory: Depression Subscale; CES-D, the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; ECOG (PSR), the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status Rating; EORTC-QLQ, the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire; ESDS, Enforced Social Dependency Scale; FACIT-B, the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-breast; FACIT-Sp-12, the 12-item Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Well-being Scale; FACT-C, the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Colorectal (Trial Outcome Index [TOI]=physical, functional domain, and concerns specific to colorectal cancer; Salsman's study TOI-R total: 21 items. Two items measuring bother from an ostomy appliance were not included in the scoring); FACT-G, the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (PWB=physical well-being, SFWB=Social/family well-being, EWB=emotional well-being, FWB=functional well-being, Gf-7=“I am content with the quality of my life right now”); FACT-Hep, the functional assessment of cancer therapy-hepatobiliary; FLIC=the Functional Living Index-Cancer; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; GSI, the Global Severity Index (measuring psychological distress); HADS, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; IES-R, Revised Impact of Events Scale; IWB, Index of Well-being (measuring psychological well-being, LAP-R, Reker's Life Attitude Profile-Revised40; LAP-R PMI, LAP-R Personal Meaning Index (to measure global meaning); LASAs, single-item Linear Analog Scales of Assessment of QOL; MHI-5, 5-item Rand Mental Health Inventory; MQOL, McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire; PAIS-SR, the Psychosocial Adjustment to Illness Scale-Self Report; PANAS, the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule; PCI-SF, Prostate Cancer Index short form; PCL, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTST) Checklist (to measure treatment-related distress); PIL, Purpose of Life Scale; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; PLT, Perceived Life Threat; POMS, Profile of Mood States; PTGI, Post-Traumatic Growth Inventory; QOL, quality of life; QUAL-E, a measure of quality of life at the end of life; SA-QLI, Self-administered Spitzer Quality of Life Index; SF-12, the 12-item short-form survey for use in the Medical Outcomes Study; SF-36, the 36-item short-form survey for use in the Medical Outcomes Study (MCS=mental component summary, PCS=physical component summary); SDS, Symptom Distress Scale; SIS, single-item scale measuring overall QOL; SWLS, the Satisfaction With Life Scale.

Sample and ethodological characteristics

Design

Thirty-two studies were cross-sectional and four evaluated the association between SpWB and QOL longitudinally.16–19

Setting and sample

Twenty-seven studies were conducted in the United States, two in Australia,20,21 two in Jordan,22,23 and one study each in Japan, Iran, Italy, the Netherlands, and Canada.24–28 Sample size ranged from 4418 to 8805.29 Thirteen studies conducted in the United States had a significant proportion of subjects that belong to racial, ethnic, or religious minorities.10,14,15,20–25,30–33 Eight studies targeted breast,19,32,34,35 prostate,30,31 or colorectal cancer patients15 only. Five studies selected patients within 12 months of diagnosis.14,16,31,36,37

Measures

In 31 studies, SpWB was measured on the 12-item Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Well-Being Scale (FACIT-Sp-12). As the 12-item FACIT-Sp was the most commonly used measure, we describe it by item in Table 2. The self-rating FACIT-Sp uses a Likert-type response format to score the items. The original validation study of the FACIT-Sp reported a two-factor model: (1) Meaning/Peace and (2) Faith.10 More recent studies, however, support a three-factor model that splits Meaning and Peace into separate factors.11,22,25,29,37 Other instruments used were the Spiritual Well-Being Scale (SWBS),7 a single-item linear analog scale assessment of overall spiritual well-being,16 the geriatric spiritual well-being scale JAREL,38 the existential well-being subscale of the McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire (MQOL),39 and the Personal Meaning Index subscale of the Reker's Life Attitude Profile-Revised (LAP-R PMI).40

Table 2.

Items by Factor of the 12-item Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Well-Being Scale (FACIT-Sp-12)

| Factor | Item |

|---|---|

| Meaning/Peace | Sp2 I have a reason for living. |

| Sp3 My life has been productive. | |

| Sp5 I feel a sense of purpose in my life. | |

| Sp8 My life lacks meaning and purpose (reversed). | |

| Sp1 I feel peaceful. | |

| Sp4 I have trouble feeling peace of mind (reversed). | |

| Sp6 I am able to reach down deep into myself for comfort. | |

| Sp7 I feel a sense of harmony within myself. | |

| Faith | Sp9 I find comfort in my faith or spiritual beliefs. |

| Sp10 I find strength in my faith or spiritual beliefs. | |

| Sp11 My illness has strengthened my faith or spiritual beliefs. | |

| Sp12 I know that whatever happens with my illness, things will be okay. |

The original psychometric validation using principal components analysis yielded two factors, labeled Meaning/Peace and Faith.10 Subsequent confirmatory11,25,29 and common factor analysis22,37 suggested a three-factor model of the FACIT-Sp-12, by dividing Meaning/Peace into separate factors Meaning and Peace.

QOL outcomes were reported as overall QOL (total score or one-item global measure), summated scores of physical health (physical component summary [PCS]) or mental health (mental component summary [MCS]), or were broken down to domains of physical, social, emotional, and functional well-being. Four studies targeted the mental27,35 or physical dimensions of QOL17,41 without assessing overall QOL.

Analysis

Eleven studies used bivariate analyses; eight used multivariate analyses, and 17 combined both. Multiple linear regression (n=12) and hierarchical linear models (n=11) were the two most commonly used multivariate statistics. Two studies used partial correlation procedures11,37; one study employed structural equation modeling42; and three studies included interaction terms in examining the association of factors of SpWB with QOL.15,31,43

Findings on the association between SpWB and QOL

Associations using the FACIT-Sp-12 to measure SpWB

Between overall SpWB and QOL

A positive association between overall SpWB and QOL remained significant after controlling for demographic and clinical variables14,20–22,32,34,36,43 with the exception of one study44 (see Table 3). However, this positive association (ranges from 0.36 to 0.70) was not equal when QOL was broken down into its physical (ranges from 0.22 to 0.54), social (ranges from 0.24 to 0.54), emotional (ranges from 0.27 to 0.58), and functional dimensions (ranges from 0.38 to 0.67). Except for two studies,11,24 overall SpWB revealed the lowest magnitude of association with the physical dimension of QOL, whereas the association with the emotional or functional dimensions was stronger. Lazenby and colleagues, in their investigations in Jordan with predominantly Muslim patients, identified an inverse association between overall SpWB and both the emotional22,23 and physical dimensions of QOL.23 These findings were not replicated in a recent study with 153 subjects diagnosed with cancer in an Iranian Muslim population.25

Table 3.

Associations between Spiritual Well-being and Quality of Life at the Scale and Factor Levels as Reported by Authors

| Overall QOL | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First author [reference] | Total score | 1-item | PWB | SWB | EWB | FWB | PCS | MCS | Multivariate statistics variables being controlled | Consistent with the majority of results? | |

| Overall Spiritual Well-Being | Tate [44] | 0.55 (NS) | QOL domains | No | |||||||

| Canada [11] | 0.50 | 0.14 | No | ||||||||

| Lazenby [23] | −0.37 | 0.54 | −0.50 | 0.57 | No | ||||||

| Lazenby [22] | (+) | NS | 0.45 | −0.27 | 0.48 | QOL domains | No | ||||

| Kruse [41] | NS | No | |||||||||

| Brady [14] | 0.58(+) | 0.48(+) | Demo, Med; QOL domains | Yes | |||||||

| Cotton [28] | 0.48 | (+) | NS | Demo, Psycho | Yes | ||||||

| Peterman [10] | 0.25 | 0.44 | 0.55 | 0.51 | Yes | ||||||

| Noguchi [24] | 0.36 | 0.24 | 0.54 | 0.67 | Yes | ||||||

| Kristeller [53] | 0.57 | 0.58 | 0.58 | Yes | |||||||

| Prince-Paul [55] | 0.59 | 0.42 | Yes | ||||||||

| Whitford [20] | 0.59 | 0.52 (+) | 0.24 | 0.43 | 0.46 | 0.55 | QOL domains | Yes | |||

| Johnson [16] | 0.59 −0.70 | Yes | |||||||||

| Daugherty [54] | 0.36 | NS | 0.24 | 0.39 | 0.38 | Yes | |||||

| Friedman [32] | 0.63 | (+) | Demo, Psycho | Yes | |||||||

| Sun [17] | 0.54 −0.27 | Yes | |||||||||

| Murphy [29] | 0.21 | 0.57 | Yes | ||||||||

| Purnell [35] | 0.67 (+) | Demo, Med | Yes | ||||||||

| Mazanec [36] | (+) | (NS) | (+) | (+) | (+) | Demo, Med, Psycho | Yes | ||||

| Whitford [21] | (+) | QOL domains | Yes | ||||||||

| Laubmeier [43] | (+) | Psycho | Yes | ||||||||

| Matthews [33] | (NS) | (+) | Demo, Med, Psycho | Yes | |||||||

| Krupski [30] | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | Demo, Med | Yes | ||||

| Jafari [25] | 0.22 | 0.45 | 0.41 | 0.49 | Yes | ||||||

| Bai [37] | 0.60 | Yes | |||||||||

| Faith | Brady [14] | 0.35(+) | 0.36 (+) | Demo, Med; QOL domains; Meaning/Peace | No | ||||||

| Lazenby [22] | (+) | NS | 0.34 | −0.27 | 0.32 | QOL domains, Meaning, Peace | No | ||||

| Edmondson[45] | NS | 0.17(NSa; -b) | (Demo, Med, Psycho)a; (Meaning/Peace)b | No | |||||||

| Salsman [15] | (+a; NSb) | (+a; NSb) | (+a; NSb) | (Demo, Med, Psycho)a; (Meaning/Peace)b | No | ||||||

| Bai [37] | NS (NS) | (NS) | (NS) | (-) | (NS) | Meaning, Peace | No | ||||

| Canada [11] | (NS) | (-) | Meaning, Peace | No | |||||||

| Whitford [20] | 0.25 | NS | 0.27 | 0.22 | 0.20 | Yes | |||||

| Whitford [21] | 0.25 | (NS) | NS | 0.24 | 0.20 | 0.24 | QOL domains, Meaning, Peace | Yes | |||

| Noguchi [24] | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.36 | 0.52 | Yes | ||||||

| Peterman [10] | NS | 0.28 | 0.35 | 0.31 | Yes | ||||||

| Kruse [41] | NS | Yes | |||||||||

| Voogt [27] | 0.29 (NS) | QOL domains, Demo, Med, Psycho | Yes | ||||||||

| Purnell [35] | 0.34 (NS) | Meaning, Peace | Yes | ||||||||

| Murphy [29] | NS | 0.25 | Yes | ||||||||

| Zavala [31] | (NS) | (NS) | (NS) | Meaning/Peace | Yes | ||||||

| Kim [42] | (NS) | (NS) | Demo, Med, Caregiver | Yes | |||||||

| Krupski [30] | (NS) | (NS) | (NS) | (NS) | (NS) | Demo, Med | Yes | ||||

| Jafari [25] | NS | 0.33 | 0.23 | 0.30 | Yes | ||||||

| Religious Well-Being | Laubmeier [43] | (NS) | Existential well-being | Yes | |||||||

| Meaning/Peace | Kruse [41] | NS | No | ||||||||

| Brady [14] | 0.62 (+) | 0.49 (+) | Demo, Med; QOL domains; Faith | Yes | |||||||

| Whitford [20] | 0.69 | 0.37 | 0.40 | 0.53 | 0.67 | Yes | |||||

| Peterman [10] | 0.31 | 0.46 | 0.57 | 0.54 | Yes | ||||||

| Noguchi [24] | 0.40 | 0.23 | 0.59 | 0.68 | Yes | ||||||

| Voogt[27] | 0.43(+) | QOL domains, Demo, Med, Psycho | Yes | ||||||||

| Purnell [35] | 0.73 (+) | Faith | Yes | ||||||||

| Edmondson[45] | 0.26 (+) | 0.59 (+) | Demo, Med, Psycho, Faith | Yes | |||||||

| Murphy [29] | 0.28 (+) | 0.67 (+) | Faith | Yes | |||||||

| Zavala [31] | (+) | (+) | (+) | Faith | Yes | ||||||

| Kim [42] | (+) | (+) | Demo, Med, Caregiver | Yes | |||||||

| Canada [11] | (+) | (+) | Faith | Yes | |||||||

| Salsman [15] | (+) | (+) | (+) | Faith, Demo, Med, Psycho | Yes | ||||||

| Krupski[30] | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | Demo, Med | Yes | ||||

| Mazzotti [26] | 0.48 | Yes | |||||||||

| Bai [37] | (+) | Faith | Yes | ||||||||

| Existential Well-Being | Cohen [28] | 0.48 | 0.57 | 0.46 | Yes | ||||||

| Laubmeier [43] | (+) | Religious well-being | Yes | ||||||||

| Meaning | Lazenby [22] | (+) | NS | 0.33 | NS | 0.25 | QOL domains, Peace, Faith | No | |||

| Whitford [21] | 0.58 | (+) | 0.30 | 0.49 | 0.35 | 0.56 | QOL domains, Peace, Faith | Yes | |||

| Murphy [29] | 0.27(+) | 0.55(+) | Peace | Yes | |||||||

| Kim [42] | (+) | (+) | Demo, Med, Caregiver | Yes | |||||||

| Canada [11] | (+) | (+) | Peace, Faith | Yes | |||||||

| Johnson [46] | (+) | Demo, Med, PCS | Yes | ||||||||

| Jafari [25] | 0.29 | 0.33 | 0.38 | 0.41 | Yes | ||||||

| Bai [37] | 0.70 (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | Peace, Faith | Yes | |||||

| Peace | Canada [11] | (NS) | (+) | Meaning, Faith | No | ||||||

| Lazenby [22] | (+) | −0.20 | 0.37 | −0.31 | 0.53 | QOL domains, Meaning, Faith | No | ||||

| Whitford [21] | 0.68 | (+) | 0.37 | 0.38 | 0.61 | 0.64 | QOL domains, Meaning, Faith | Yes | |||

| Murphy [29] | 0.25(+) | 0.66(+) | Meaning | Yes | |||||||

| Kim [42] | (+) | (+) | Demo, Med, Caregiver | Yes | |||||||

| Jafari [25] | 0.24 | 0.37 | 0.35 | 0.42 | Yes | ||||||

| Bai [37] | 0.63 (+) | (+) | (+) | Meaning, Faith | Yes | ||||||

Blank cells indicate that authors did not analyze the association of the item in the column with spiritual well-being.

(+) indicates a positive association reported in multivariate statistics; (-) indicates a negative association reported in multivariate statistics; (NS) indicates an insignificant association reported in multivariate statistics. Values without a (+) or a (-) indicate a zero-order (simple) correlation coefficient reported in bivariate statistics. When both bivariate and multivariate analyses were reported in a single study, the correlation coefficient appears first followed by the multivariate result in the corresponding cell.a,b

“Yes” denotes study results are in agreement with the major findings of this review; “No” indicates results are in conflict with the major findings on either the scale or factor level.

Demo, demographic variables; EWB, emotional well-being; FWB, functional well-being; MCS, mental component summary; Med, medical/clinical variables; PCS, physical component summary; Psycho, psychosocial variables; PWB, physical well-being; QOL, quality of life; SWB, social/family well-being.

Between factors of SpWB and QOL

Faith

Eighteen studies examined the relative contribution of the Faith factor of SpWB to QOL. When examined alone in simple correlations, Faith positively associated with overall QOL (ranges from 0.25 to 0.36), mental health (ranges from 0.17 to 0.34), and the social (ranges from 0.20 to 0.34), emotional (ranges from 0.20 to 0.36), and functional (ranges from 0.20 to 0.52) dimensions of QOL, with one exception.37 In the studies that controlled for demographic and clinical variables, Faith remained significantly associated with overall QOL.14–15 However, after removing the effect of Meaning and Peace, treated either as one or two factors, the association between Faith and QOL remained significant in only two studies,14,22 and an inverse association with mental health or emotional well-being was reported in three studies.11,37,45 Zavala and colleagues31 did not identify an association between Faith and mental or physical health when examined together with the Meaning/Peace factor. Instead they found that higher Meaning/Peace was associated with better physical health and less pain independent of Faith; however, when the Meaning/Peace score was low, a higher level of Faith were associated with poorer physical health and more pain.

Meaning/Peace as one factor

Among the 16 studies that examined the Meaning/Peace as one factor and its association with QOL, a positive association was evident in all except for one study.41 This positive association was consistent for overall QOL (ranges from 0.49 to 0.70) and for physical (ranges from 0.25 to 0.28) and mental health (ranges from 0.55 to 0.73).10,20,24,26 The correlation between Meaning/Peace and mental health was found to be stronger than physical health in three studies,11,29,45 although not for all.30,31 The positive association remained significant after controlling for demographic and clinical variables15,30,42,45 and the Faith factor.11,15,29,35,37

Meaning and Peace as two factors

Seven studies divided the Meaning/Peace factor into two separate factors, Meaning and Peace, when examining associations between SpWB and QOL.11,21,22,25,29,37,42 Whitford and Olver21 identified a positive association between Meaning and Peace as separate factors and overall QOL, as well as for the physical, functional, social, and emotional dimensions of QOL. Two studies found that Peace and Meaning as separate factors were both positively related to mental and physical health as measured by the 36-item short-form survey for use in the Medical Outcomes Study (SF-36).29,42 When the Meaning and Faith factors were controlled, one study found Peace was more related to mental health than physical health.11 Two studies found that Peace was more related to emotional well-being than social or physical well-being.21,37 Lazenby and colleagues22 identified an inverse bivariate association between the Peace factor and both physical and emotional well-being, whereas Meaning was not significantly related to either physical or emotional well-being.

Associations using other scales to measure SpWB

Three studies in this review examined the association between QOL and SpWB on scales other than the FACIT-Sp-12. Existential well-being measured as one subscale of the MQOL strongly correlated with a single-item scale measuring overall QOL and moderately correlated to the self-administered Spitzer Quality of Life Index (SA-QLI).28 Laubmeier and colleagues43 identified a positive association between existential well-being (measured on the SWBS) and overall QOL. Johnson and colleagues46 reported that global meaning measured on LAP-R PMI was positively associated with mental health (on the SF-36).

Discussion

The questions that motivated this review were whether SpWB is associated with QOL at the scale and factor levels for individuals with cancer and whether these associations hold in multivariate analysis. To answer these questions, we reviewed 36 studies in 35 full-text articles, one of which reported two studies. In the majority of studies, overall SpWB at the scale level and Meaning/Peace as one or two factors of the FACIT-Sp-12 were positively associated with QOL outcomes. These associations remained significant independent of sample or methodological characteristics.

In our review we found Meaning/Peace as one factor is consistently associated with mental health and emotional well-being, of which the magnitude of association ranged from 0.43 to 0.73.27,35 It has been suggested that SpWB and psychological well-being may have considerable overlap.48,49 The maximum magnitude (0.73) of association in our review suggests <53.3% of the association's variance is accounted for by construct similarity. If there is overlap it is not complete. Nevertheless, the item similarity found between the indicators of SpWB and general mental health might have inflated this relationship (e.g., “I feel peaceful.”). The stable association between Meaning/Peace and emotional well-being or mental health deserves further exploration.

The majority of studies included in our review did not find an independent association between Faith and QOL. Some studies found an inverse association between Faith and mental health11,31,45 or emotional well-being,37 when controlling for Meaning and Peace simultaneously. Only two studies in our review supported a positive association between Faith and QOL when controlling for Meaning/Peace. The sample of one of the studies comprised mostly Hispanic and African-American cancer patients in the United States.14 The other sample was predominantly Muslim Arab cancer patients.22 Degrees of measurement variance among certain sample characteristics may explain the lack of association between Faith and QOL, as the meaning of the term “faith” may differ for different religious groups10,47,50 and ethnicities.51,52

It is important to note the variety of multivariate statistics employed in studies, as findings tend to change depending on the variables being controlled for. For example, Edmondson and colleagues45 reported in a U.S. sample of 237 cancer patients that Faith was positively associated with mental health on the SF-12. However, when demographic and clinical variables were held constant, the association did not remain significant; and when the Meaning/Peace factor was held constant, the direction of association was reversed.

The work reported here does not permit the inference that SpWB or its Meaning/Peace factor has a causal influence on the QOL outcomes to which we linked it. Caution is warranted when using predominantly one-time cross-sectional studies to describe associations between SpWB and QOL, as the strength of the associations may fluctuate over time.16–19 It is also noted that not all studies examined correlations at the scale and factor levels, resulting in missing cells in Table 3. Future studies may consider addressing the bias issue in reporting. We suggest that, in articles presenting findings on associations between SpWB and QOL, researchers justify the selected analytic strategy. Finally, the association between QOL and Meaning/Peace as individual factors requires further exploration.

Conclusions

This review suggests consistent and independent associations between QOL and overall SpWB, as well as between QOL and Meaning/Peace, when considered as one or two factors of the FACIT-Sp-12. These associations remained significant across a wide array of methodological and sample characteristics. Moreover, the incremental validity of SpWB and Meaning/Peace factor(s) over QOL domains suggests that these associations cannot be explained by construct overlap, and SpWB is more than emotions alone. These findings lend support for clinician integrating assessment of Meaning and Peace into QOL assessments of patients with cancer and for research including Meaning and Peace as QOL end points in cancer clinical trials. The inconsistent association between the Faith factor of the FACIT-Sp-12 and QOL, and the extent to which SpWB and QOL overlap require further study.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Ruth McCorkle who made valuable suggestions. This study was partly supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the National Institutes of Nursing Research (NINR) (Grant number NR011872, Ruth McCorkle, PI).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Oxford Handbook of Palliative Care. Watson M, Lucas C, Hoy A, Back L. (eds.): New York: Oxford University Press, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zinnbauer BJ, Pargament KI, Core B, et al. : Religion and spirituality: Unfuzzying the fuzzy. J Sci Study Relig 1997;36:549–564 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pew Research Center: “Nones” on the rise: One-in-five adults have no religious affiliation. The Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life (ed). Washington, D.C., 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Büssing A: Measures. In: Cobb M, Puchalski CM, Rumbold B. (eds): Oxford Textbook of Spirituality in Healthcare. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012, pp. 323–331 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sulmasy DP: A biopsychosocial-spiritual model for the care of patients at the end of life. Gerontologist 2002;42(spec.3):24–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wulff DM: The psychology of religion: An overview. In: Shafranske EP. (ed): Religion and the Clinical Practice of Psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 1996, pp. 43–70 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ellison CW: Spiritual well-being: Conceptualization and measurement. J Psychol Theol 1983;11:330–340 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paloutzian RF, Bufford RK, Wildman AJ: Spiritual well-being scale: Mental and physical health relationships. In: Cobb M, Puchalski CM, Rumbold B. (eds): Oxford Textbook of Spirituality in Healthcare. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012, pp. 353–358 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fitchett G, Peterman AH, Cella DF: Spiritual beliefs and quality of life in cancer and HIV patients. Paper presented at: the Society for Scientific Study of Religion, Nashville, Tennessee, 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 10.*Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Brady MJ, et al. : Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Well-Being Scale (FACIT-Sp). Ann Behav Med 2002;24:49–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.*Canada AL, Murphy PE, Fitchett G, et al. : A 3-factor model for the FACIT-Sp. Psychooncology 2008;17:908–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. : Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis: The PRISMA statement. Plos Med 2009;6:1–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. : Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2008;61:344–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.*Brady MJ, Peterman AH, Fitchett G, et al. : A case for including spirituality in quality of life measurement in oncology. Psychooncology 1999;8:417–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.*Salsman JM, Yost KJ, West DW, Cella D: Spiritual well-being and health-related quality of life in colorectal cancer: A multi-site examination of the role of personal meaning. Support Care Cancer 2011;19:757–764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.*Johnson ME, Piderman KM, Sloan JA, et al. : Measuring spiritual quality of life in patients with cancer. J Support Oncol 2007;5:437–442 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.*Sun V, Ferrell B, Juarez G, Wagman LD, Yen Y, Chung V: Symptom concerns and quality of life in hepatobiliary cancers. Oncol Nurs Forum 2008;35:E45–E52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.*Smith SK, Herndon JE, Lyerly HK, et al. : Correlates of quality of life-related outcomes in breast cancer patients participating in the Pathfinders pilot study. Psychooncology 2011;20:559–564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.*Samuelson BT, Fromme EK, Thomas CR: Changes in spirituality and quality of life in patients undergoing radiation therapy. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2012;29:449–454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.*Whitford HS, Olver IN, Peterson M: Spirituality as a core domain in the assessment of quality of life in oncology. Psychochooncology 2008;17:1121–1128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.*Whitford HS, Olver IN: The multidimensionality of spiritual wellbeing: Peace, meaning, and faith and their association with quality of life and coping in oncology. Psychooncology 2012;21:602–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.*Lazenby M, Khatib J, Al-Khair F, et al. : Psychometric properties of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy—Spiritual Well-being (FAICT-Sp) in an Arabic-speaking, predominantly Muslim population. Psychooncology 2013;22:220–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.*Lazenby M, Khatib J: Associations among patient characteristics, health-related quality of life, and spiritual well-being among Arab Muslim cancer patients. J Palliat Med 2012;15:1321–1324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.*Noguchi W, Ohno T, Morita S, et al. : Reliability and validity of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual (FACIT-Sp) for Japanese patients with cancer. Support Care Cancer 2004;12:240–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.*Jafari N, Zamani A, Lazenby M, et al. : Translation and validation of the Persian version of the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy—Spiritual well-being scale (FACIT-Sp) among Muslim Iranians in treatment for cancer. Palliat Support Care 2013;11:29–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.*Mazzotti E, Mazzuca F, Sebastiani C, et al. : Predictors of existential and religious well-being among cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 2011;19:1931–1937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.*Voogt E, van der Heide A, van Leeuwen AF, et al. : Positive and negative affect after diagnosis of advanced cancer. Psychooncology 2005;14:262–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.*Cohen SR, Mount BM, Tomas JJN, et al. : Existential well-being is an important determinant of quality of life: Evidence from the McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire. Cancer 1996;77:576–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.*Murphy PE, Canada AL, Fitchett G, et al. : An examination of the 3-factor model and structural invariance across racial/ethnic groups for the FACIT-Sp: A report from the American Cancer Society's study of cancer survivors-II (SCS-II). Psychooncology 2010;19:264–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.*Krupski TL, Kwan L, Fink A, et al. : Spirituality influences health related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Psychooncology 2006;15:121–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.*Zavala MW, Maliski SL, Kwan L, et al. : Spirituality and quality of life in low-income men with metastatic prostate cancer. Psychooncology 2009;18:753–761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.*Friedman LC, Barber CR, Chang J, et al. : Self-blame, self-forgiveness, and spirituality in breast cancer survivors in a public sector setting. J Cancer Educ 2010;25:343–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.*Matthews AK, Tejeda S, Johnson TP, et al. : Correlates of quality of life among African American and white cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs 2012;35:355–364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.*Cotton SP, Levine EG, Fitzpatrick CM, et al. : Exploring the relationships among spiritual well-being, quality of life, and psychological adjustment in women with breast cancer. Psychooncology 1999;8:429–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.*Purnell JQ, Anderson BL, Wilmot JP: Religious practice and spirituality in the psychological adjustment of survivors of breast cancer. Couns Values 2009;53:165–180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.*Mazanec SR, Daly BJ, Douglas SL, et al. : The relationship between optimism and quality of life in newly diagnosed cancer patients. Cancer Nurs 2010;33:235–243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.*Bai M, Dixon JK: Exploratory factor analysis of the 12-item Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy–Spiritual Well-being Scale (FACIT-Sp-12) in people newly diagnosed with advanced cancer. J Nurs Meas 2014. (accepted September2013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hungelmann J, Kenkel-Rossi E, Klassen L, Stollenwerk R: Focus on spiritual well-being: Harmonious interconnectedness of mind-body-spirit—Use of the JAREL spiritual well-being scale. Geriatr Nurs 1996;17:262–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cohen SR, Mount BM, Strobel MG, et al. : The McGill Quality of life Questionnaire: A measure of quality of life appropriate for people with advanced disease. A preliminary study of validity and acceptability. Palliative Med 1995;9:207–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.The Life Attitude Profile-Revised (LAP-R): Procedures Manual (Research Edition). Reker GT. (ed). Student Psychologists Press, Peterborough, ON, 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 41.*Kruse BG, Ruder S, Martin L: Spirituality and coping at the end of life. J Hosp Palliat Nurs 2007;9:296–304 [Google Scholar]

- 42.*Kim Y, Carver CS, Spillers RL, et al. : Individual and dyadic relations between spiritual well-being and quality of life among cancer survivors and their spousal caregivers. Psychooncology 2011;20:762–770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.*Laubmeier KK, Zakowski SG, Bair JP: The role of spirituality in the psychological adjustment to cancer: A test of the transactional model of stress and coping. Int J Behav Med 2004;11:48–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.*Tate DG, Forchheimer M: Quality of life, life satisfaction, and spirituality-comparing outcomes between rehabilitation and cancer patients. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2002;81:400–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.*Edmondson D, Park CL, Blank TO, et al. : Deconstructing spiritual well-being: Existential well-being and HRQOL in cancer survivors. Psychooncology 2008;17:161–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.*Johnson Vickberg SM, Duhamel KN, Smith MY, et al. : Global meaning and psychological adjustment among survivors of bone marrow transplant. Psychooncology 2001;10:29–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lazenby JM: On “spirituality,” “religion,” and “religions”: A concept analysis. Palliat Support Care 2010;8:469–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koenig HG: Concerns about measuring “spirituality” in research. J Nerv Ment Dis 2008;196:349–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Meezenbroek Ede J, Garssen B, Van den Berg M, et al. : Measuring spirituality as a universal human experience: Development of the Spiritual Attitude and Involvement List (SAIL). J Psychosoc Oncol 2012;30:141–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moberg DO: Subjective measures of spiritual well-being. Rev Relig Res 1984;25:351–364 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pew Research Center: Changing faiths: Latinos and the transformation of American religion. Pew Hispanic Center and Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life. Washington, D.C., 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sahgal N, Smith G: A religious portrait of African-Americans. Washington, D.C.: Pew Research Center, 2009. www.pewforum.org/2009/01/30/a-religious-portrait-of-african-americans/ (Last accessed September22, 2013) [Google Scholar]

- 53.*Kristeller JL, Rhodes M, Cripe LD, et al. : Oncologist Assisted Spiritual Intervention Study (OASIS): Patient acceptability and initial evidence of effects. Int J Psychiatry Med 2005;35:329–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.*Daugherty CK, Fitchett G, Murphy PE, et al. : Trusting god and medicine: Spirituality in advanced cancer patients volunteering for clinical trials of experimental agents. Psychooncology 2005;14:135–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.*Prince-Paul M: Relationships among communicative acts, social well-being, and spiritual well-being on the quality of life at the end of life in patients with cancer enrolled in hospice. J Palliat Med 2008;11:20–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]