SUMMARY

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a rare systemic inflammatory syndrome that results from unrestrained immune cell activation. Despite significant advances in the understanding of the pathophysiology of HLH, interventions remain limited for this often-fatal condition. Secretory sphingomyelinase (S-SMase) is a pro-inflammatory lipid hydrolase that is upregulated in several inflammatory conditions, including HLH. S-SMase promotes the formation of ceramide, a bioactive lipid implicated in several human disease states. However, the role of the S-SMase/ceramide pathway in HLH remains unexplored. To further evaluate the role of S-SMase upregulation in HLH, we tested the serum of patients with HLH (n=16; primary=3, secondary=13) and healthy control patients (n=25) for serum S-SMase activity with tandem sphingolipid metabolomic profiling. Patients with HLH exhibited elevated levels of serum S-SMase activity, with concomitant elevations in several ceramide species and sphingosine, while levels of sphingosine-1-phosphate were significantly decreased. Importantly, the ratio of C16-ceramide:sphingosine was uniquely elevated in HLH patients that died despite appropriate treatment, but remained low in HLH patients that survived, suggesting that this ratio may be of prognostic significance. Together, these results demonstrate upregulation of the S-SMase/ceramide pathway in HLH, and suggest that the balance of ceramide and sphingosine determine clinical outcomes in HLH.

Keywords: hemophagocytic syndrome, sphingolipids, inflammation, acid sphingomyelinase, sphingosine

INTRODUCTION

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH, hemophagocytic syndrome) is a devastating multisystem condition characterized by severe and pathologic activation of the immune system [1, 2]. While normal immune responses are self-limited via well coordinated cell-mediated cytotoxic death of immune effectors, in HLH impaired inactivation of antigen-presenting cells (macrophages, histiocytes) and CD8+ T lymphocytes leads to persistent and potent pro-inflammatory responses [1]. HLH occurs in both familial (primary) and sporadic (secondary) forms, with the former associated with defined mutations in genes involved in inactivation of T-lymphocyte responses, specifically the perforin/granule-mediated cytotoxicity pathway [3]. Primary HLH is rare (1 case per 50,000 live births) and follows an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern [4]. Secondary HLH is most commonly seen in the setting of Epstein-Barr viral (EBV) infection, but is also seen in patients with HIV, hematologic malignancies, and rheumatologic conditions [2]. However, it is becoming increasingly apparent that patients with adult-onset HLH can have underlying genetic defects in perforin or other HLH-associated genes, in addition to the role of viruses and malignancies [5, 6].

The pathophysiologic progression of HLH begins with a predisposing immunodysfunction, which leads to impaired attenuation of immune cell activation, leading to hypercytokinemia [7, 8]. Clinically, this robust and persistent inflammatory response manifests with fever, splenomegaly, elevated ferritin, elevated soluble IL-2Rα (CD25), and elevated soluble CD163. Lastly, the persistent inflammation leads to abnormal immunopathology evidenced by cytopenias, decreased fibrinogen, elevated triglycerides, hepatitis, CNS involvement, and hemophagocytosis. Importantly, early in its course it may mimic systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) or sepsis and therefore diagnosis may be delayed unless there is high clinical suspicion [9]. Results from the HLH-94 study demonstrate a 5-yr survival greater than 50%, a marked improvement from the 4% survival reported in 1983 by Janka et al [10]. Additionally, hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) is considered curative for patients with familial HLH, but is also used in patients with progression on standard treatment or in patients with recurrence [7, 11, 12]. Prompt recognition and initiation of treatment is essential to prevent mortality and morbidity.

Sphingolipids (SPLs) are a diverse class of bioactive lipids that are increasingly recognized as potent signaling molecules, and have been implicated in numerous cellular processes including cell death, differentiation, senescence, and inflammation [13]. Elevations in ceramide (Cer, N-acyl sphingosine), one of the most extensively studied SPLs, has classically been associated with restricted cell growth, while metabolites sphingosine (Sph) and sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) have been ascribed more pro-growth and pro-inflammatory roles [13, 14]. Cellular levels of these bioactive lipids are tightly regulated by sphingolipid metabolizing enzyme as well as transport proteins. Importantly, SPLs also exist extracellularly [15]. Alterations in serum levels of Cer, Sph and S1P have been associated with several disease states, including atherosclerosis [16], coronary artery disease [17], and sepsis [18]. Importantly, modulation of various enzymes of SPL metabolism have been shown not only normalize lipid levels, but also modify disease progression [16, 19].

Acid sphingomyelinase (aSMase, EC 3.1.4.2) is a soluble lysosomal enzyme that hydrolyzes the phosphodiester bond sphingomyelin (SM) within biological membranes to release inert phosphorylcholine and the bioactive ceramide (Cer) [20]. Deficiency of aSMase in humans leads to Niemann-Pick disease (types A and B), a lysosomal storage disorder associated with elevations in SM in various cells and tissues [21]. Importantly, aSMase has been implicated in cell death and inflammatory signaling, and an alternatively trafficked form of aSMase can be secreted extracellularly, a process that is promoted by inflammatory cytokines [22, 23]. Secretory acid spingomyelinase (S-SMase) levels are increased 2-3 fold in response to inflammatory cytokines, in vitro and in vivo [22, 24]. Serum S-SMase activity is also upregulated in several human disease states characterized by systemic inflammation, including sepsis [25-27]. Interestingly, serum S-SMase activity was dramatically increased in a small case series of patients with HLH with documented hypercytokinemia [28], however the functional consequences of this change, especially in regulating the levels of bioactive lipids, has not been evaluated.

In this study, we demonstrate that serum S-SMase activity is elevated in patients with both primary and secondary HLH, and using sphingolipidomic metabolic profiling reveal marked alterations in levels of key bioactive SPLs. This is the first study using a metabolomic approach to identify novel changes in bioactive lipid mediators associated with HLH. The results of this study may set the foundation for the development of novel sphingolipid-based approaches to abrogate the exaggerated inflammatory response in HLH.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient Information and Inclusion Criteria

We collected data on sixteen patients who were diagnosed with hemophagocytosis from 2010-2011 at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston, SC. The research protocol was approved by the MUSC Institutional Review Board. We used archived samples and analyzed data retrospectively. Inclusion criteria were as follows: presence of hematological abnormalities on complete blood count (CBC) (bi- or trilineage cytopenias) and pathological evidence of hemophagocytosis on biopsy specimen upon review by the hematopathologist at our institution. Patients on whom the biopsy specimen could not be obtained for review were excluded from this analysis. Data collected on each patient included age, presence of co-morbidities or any predisposing factors, presence or absence of hepatosplenomegaly, hemoglobin level, absolute neutrophil count, platelet count, ferritin, triglyceride levels, total bilirubin, prothrombin time, fibrinogen, and soluble interleukin-2 receptor α (sIL-2Rα). Control patient serum was obtained from archived control samples. All patients diagnosed with HLH received treatment according to the HLH 2004 protocol [29].

Sixteen patients diagnosed with primary or secondary HLH were enrolled in the study from 2010-2011. Of those 16, three children were diagnosed with familial HLH confirmed by presence of a known mutation (No.5 – ΔSTXBP2, encoding Munc 18-2; No.15 and No.16 – ΔPRF1, perforin). Patients diagnosed with secondary HLH carried eight different diagnoses, including diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), sepsis/septicemia, sarcoidosis, subacute bacterial endocarditis (SBE), anaplastic T-cell lymphoma, Epstein-Barr viral infection, Felty’s syndrome, and T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder (see Table I). All patients exhibited biopsy-confirmed hemophagocytosis (Fig. S1), and demonstrated laboratory abnormalities consistent with HLH (Table S2). All sixteen patients met the diagnostic criteria set forth by the HLH-2004 protocol (Table S1) fulfilling ≥5 of the 8 diagnostic criteria or molecular diagnosis consistent with HLH (Table I). At least one patient (No. 8) who developed HLH was suspected of primary HLH, but genetic testing was unrevealing. This patient was given the diagnosis of secondary HLH with no known etiology.

Table I.

Patient Demographic and Clinical Information

| Patient No. | Age/Sex | Race | Fever | Organomegaly | Etiology | Outcome | HLH Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 68 yr/F | Hisp | No | No | DLBCL s/p BMT | Died | 5/8 criteria |

| 2 | 42 yr/M | C | Yes | No | Sepsis, ARDS | Died | 6/8 criteria |

| 3 | 23 yr/M | AA | Yes | No | Sarcoidosis | Died | 6/8 criteria |

| 4 | 43 yr/M | AA | Yes | No | Subacute bacterial endocarditis | Died | 5/8 criteria |

| 5 | 11 yr/M | C | Yes | Hepatosplenomegaly | Familial HLH type 5 (s/p BMT) | Recovered | ⊕ mutation |

| 6 | 61 yr/M | C | Yes | Adenopathy | Anaplastic T-cell lymphoma | Died | 5/8 criteria |

| 7 | 16 mth/M | Hisp | Yes | No | EBV infection | Recovered | 5/8 criteria |

| 8 | 3 yr/M | Hisp | Yes | Hepatomegaly | Unknown | Recovered | 7/8 criteria |

| 9 | 63 yr/F | C | Yes | Splenomegaly | Felty’s syndrome | Died | 5/8 criteria |

| 10 | 64 yr/M | C | Yes | No | T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder | Died | 6/8 criteria |

| 11 | 34 yr/F | AA | No | Hepatosplenomegaly | Unknown | Died | 5/8 criteria |

| 12 | 6 yr/F | AA | Yes | No | Sepsis | Recovered | 5/8 criteria |

| 13 | 10 yr/M | Asian | Yes | Hepatomegaly | Anaplastic T-cell lymphoma | Recovered | 5/8 criteria |

| 14 | 65 yr/F | AA | Yes | No | Sepsis | Died | 5/8 criteria |

| 15 | 4 mth/F | C | Yes | No | Familial HLH type 2 | Recovered | ⊕ mutation |

| 16 | 4 mth/M | C | Yes | No | Familial HLH type 2 (s/p BMT) | Recovered | ⊕ mutation |

Serum collection and preparation

Blood samples were collected by venipuncture in 5-mL vacu-tainer tubes without anticoagulant and allowed to clot for 10-15 minutes. Samples were then centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 10 minutes in a refrigerated centrifuge. The clot was then removed and 0.5ml aliquots of serum were transferred to polypropylene tubes and stored at -80C. Serial or single measurements were obtained (depending on sample availability).

In vitro Serum Sphingomyelinase Activity Assay

The S-SMase activity assay was performed as previously described [23]. Briefly, porcine brain sphingomyelin (0.2 mM) mixed with 14C-sphingomyelin (radiolabeled in the choline moiety, specific radioactivity = 1.5 × 105 cpm/μL) were incubated with serum samples (1:10 dilution – 10 μL serum + 90 μL of 0.2% Triton X-100, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, to a final volume of 100 μL) in Triton X-100 micelles in a buffer containing 250 mM sodium acetate (pH 5.00) and 0.2 mM ZnCl2 (S-SMase) to a final concentration of 0.1 mM SM with either 0.1 mM ZnCl2 (S-SMase). The reaction was run for 3 hr at 37°C and terminated with the addition of 1.5 mL CHCl3: MeOH (2:1, v/v) followed by 0.4 mL water. Samples were vortexed, centrifuged (5 min, 3,000 rpm) and 0.8 mL of the aqueous/methanolic phase was removed for scintillation counting. The assay was linear with respect to time and volume of serum, and cleavage of substrate was <10%.

Sphingolipidomic Analysis

Aliquots of serum (100 μL) were frozen in glass vials at -80°C and were then submitted for sphingolipidomic analysis by reverse-phase high pressure liquid chromatography coupled to electrospray ionization followed by separation by MS. Analysis of sphingoid bases, ceramides and sphingomyelins was performed on a Thermo Finnigan TSQ 7000 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer, operating in a multiple reaction-monitoring positive ionization mode, as described [30]. All sphingolipid analytes contain a d18:1 sphingoid backbone. Notation of SPL species therefore imply a d18:1 sphingoid base backone (e.g. C16-ceramide represents d18:1/16:0 ceramide) [31].

Statistical Analysis

Data are represented as mean ± standard error of the mean (S.E.M.), unless otherwise indicated. Non-Gaussian distribution was assumed and data were analyzed by non-parametric 2-tailed, unpaired Mann-Whitney U test or Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s post-test statistical analyses. Statistical analyses were performed using Prism/GraphPad software.

RESULTS

Elevated Serum S-SMase Activity in Primary and Secondary HLH

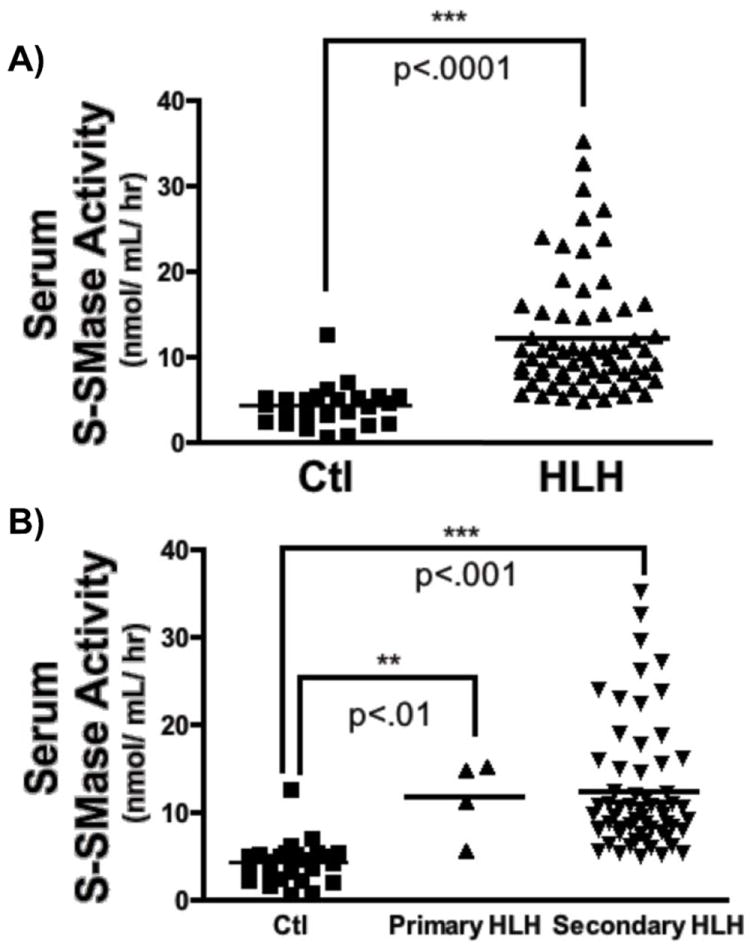

After collecting sera from the sixteen patients with documented HLH and twenty-five healthy volunteer controls, the activity of (i.e. S-SMase) was assessed, as described above in METHODS. Serum S-SMase activity was elevated 2-3 fold in patients with HLH (control: 4.28 ± 0.49 nmol/mL/hr vs. HLH: 12.30 ± 0.86 nmol/mL/hr; p<.001), as shown in Fig. 1A. Subgroup analysis of serum samples from patients with documented mutations consistent with familial HLH and all other cases, revealed comparable upregulation of S-SMase activity in patients with both primary and secondary HLH (Fig. 1B). These data indicate that S-SMase activity is significantly upregulated in both primary and secondary HLH, thereby confirming and extending the results of Takahashi et al [28].

Figure 1. Serum S-SMase activity in healthy controls and HLH patients.

A) Sera prepared from healthy volunteers (Ctl; n=25) and patients with HLH (n=16, 66 total sera samples) were processed for in vitro Zn2+-dependent acid SMase activity, as described above (see Methods). (2-tailed, unpaired Man-Whitney test***p<.001). B) S-SMase activity was determined for patients with primary (n=3; 4 samples) and secondary (n=13, 62 samples). Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s post-test, **p<.01, ***p<.001.

Dysregulation of the Serum Sphingolipidome in HLH

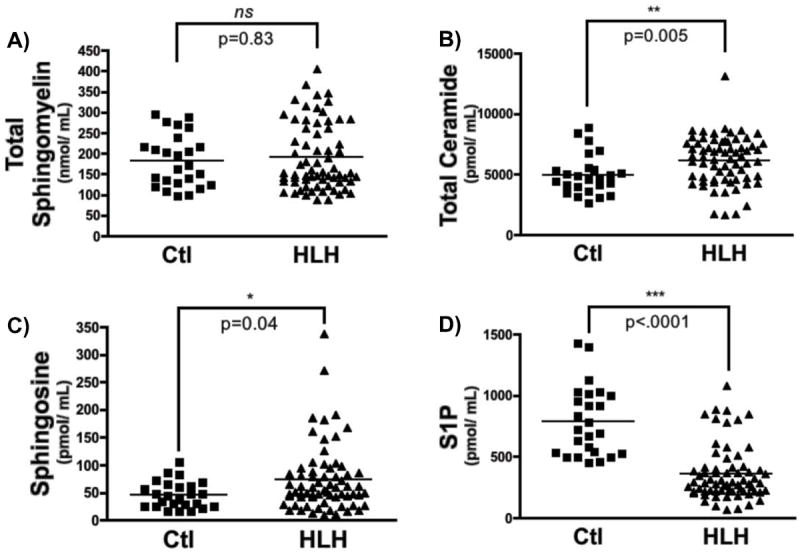

To determine if elevations in S-SMase evident in patients with HLH were associated with changes in the serum sphingolipid profile, aliquots of serum were analyzed by mass spectrometric profiling, as described in METHODS. Initial action of S-SMase would yield elevations in Cer, with expected decreases in SM. Despite elevations in S-SMase activity, serum SM levels were unchanged in patients with HLH compared to control patients (Fig. 2A). Interestingly, serum Cer and Sph levels were significantly increased while serum S1P levels were drastically decreased (Fig. 2B-D). Of note, the action of a ceramidase (CDase) is necessary for generation of Sph from the deacylation of Cer, suggesting that other enzymes may be upregulated in addition to S-SMase.

Figure 2. Sphingolipid profile in serum of healthy controls and HLH patients.

Sphingolipids were measured sera (100 μL) from healthy volunteers (Ctl; control) and patients with HLH, as described in Methods. A) Total sphingomyelin, B) total ceramide, C) sphingosine, and D) sphingosine-1-phosphate, (n=25 for control, n=66 for HLH; 2-tailed, unpaired Mann-Whitney test; ns – not statistically significant, *p<.05, **p<.01, ***p<.001).

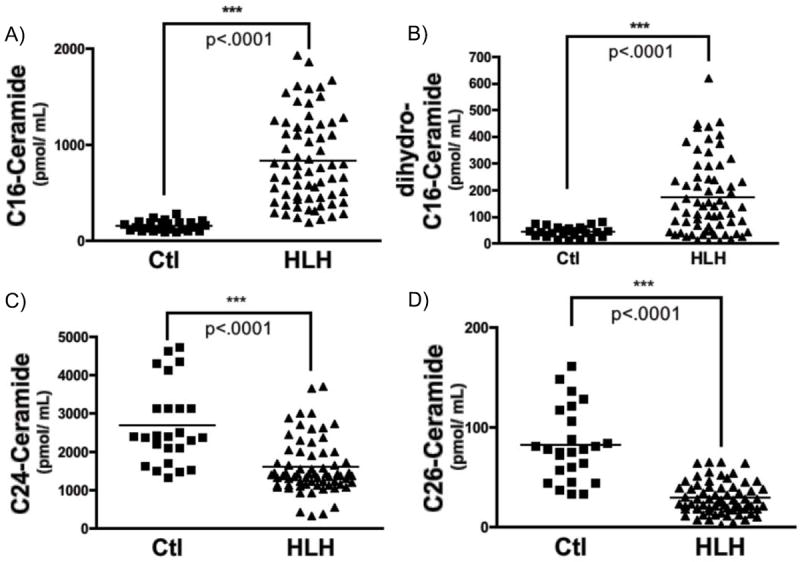

Total SM and Cer levels represent the composite of several SM and Cer species, each with different acyl chain lengths covalently linked to the Sph backbone, with varying substituents, and with variable saturation of a 4-5 trans double bone of the Sph backbone [32]. To determine if levels of individual SM and Cer species were altered in HLH, subgroup analysis of individual species was performed (Table II and III). Subgroup analysis of SM species (Table II), revealed statistically significant decreased in 6 of 13 sphingomyelins (C18:1-, C22-, C22:1-, C24-, C26-, and lyso-SM). Surprisingly, levels of C16-SM were slightly elevated (1.36-fold) in sera from HLH patients, although this was not statistically significant (p=0.08). Analysis of individual ceramide species revealed >2-fold elevations in six different ceramides (C14-, C16-, C18-, C18:1-, C20:1-, and C24:1-Cer), including a >5-fold elevation in serum C16-ceramide in patients with HLH (control: 156.3 ± 10.16 pmol/mL vs. HLH: 820.2 ± 56.29 pmol/mL; p<.001). Additionally, levels of the desaturated form of C16-Cer (dihydro-C16-Cer) were elevated nearly 4-fold in HLH samples. Importantly, not all Cer species were elevated, and levels of specific very long-chain Cer species (C24-Cer, C26-Cer) were actually decreased significantly (Fig. 3, Table III).

Table II.

Serum Sphingomyelin Profile in Control and HLH Samples

| Control | HLH | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sphingomyelin | Mean (pmol/mL) | Std. Deviation | Std. Error | Mean (pmol/mL) | Std. Deviation | Std. Error | p-value | Fold-Change |

| C14 | 9144 | 11040 | 2208 | 8219 | 9610 | 1183 | 0.411 | 0.90 |

| C16 | 80130 | 59400 | 11880 | 108700 | 71810 | 8840 | 0.022 | 1.36 |

| C18 | 8535 | 3375 | 674.9 | 6730 | 4455 | 548.4 | 0.045 | 0.79 |

| C18:1 | 4163 | 1481 | 296.3 | 2844 | 1720 | 211.8 | 0.001 | 0.68 |

| C20 | 9601 | 8634 | 1727 | 6821 | 5908 | 727.3 | 0.125 | 0.71 |

| C20:1 | 3306 | 3225 | 645 | 3000 | 2428 | 298.8 | 0.531 | 0.91 |

| C22 | 18300 | 10020 | 2005 | 11990 | 6389 | 786.5 | 0.0002 | 0.66 |

| C22:1 | 13870 | 6071 | 1214 | 9157 | 4593 | 565.3 | 0.0003 | 0.66 |

| C24 | 10970 | 3096 | 619.2 | 6399 | 2579 | 317.5 | <.0001 | 0.58 |

| C24:1 | 25000 | 6504 | 1301 | 26720 | 7759 | 955.1 | 0.225 | 1.07 |

| C26 | 23.66 | 15.23 | 3.046 | 13.6 | 16.14 | 2.017 | 0.002 | 0.57 |

| C26:1 | 109.6 | 34.74 | 6.948 | 89.98 | 55.93 | 6.885 | 0.101 | 0.82 |

| Lyso | 21.22 | 46.8 | 9.36 | 8.758 | 11.69 | 1.439 | 0.030 | 0.41 |

| Total | 183200 | 63130 | 12630 | 190600 | 82080 | 10100 | 0.848 | 1.04 |

Table III.

Serum Ceramide Profile in Control and HLH Samples

| Control | HLH | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ceramide | Mean (pmol/mL) | Std. Deviation | Std. Error | Mean (pmol/mL) | Std. Deviation | Std. Error | p-value | Fold-Change |

| C14 | 50.7 | 30.8 | 6.16 | 120.2 | 136 | 16.75 | 0.0002 | 2.37 |

| C16 | 156.3 | 50.8 | 10.16 | 820.2 | 460.8 | 56.29 | <.0001 | 5.25 |

| C18 | 158.1 | 86.28 | 17.26 | 564.9 | 400.1 | 49.25 | <.0001 | 3.57 |

| C18:1 | 39.98 | 24.83 | 4.966 | 104.4 | 57.73 | 7.106 | <.0001 | 2.61 |

| C20 | 387.5 | 215.4 | 43.08 | 708.8 | 483.7 | 59.54 | 0.0004 | 1.83 |

| C20:1 | 19.05 | 8.53 | 1.706 | 41.47 | 30.34 | 3.734 | 0.001 | 2.18 |

| C22 | 480.7 | 227.2 | 45.45 | 518.5 | 259.2 | 31.91 | 0.519 | 1.08 |

| C22:1 | 95.5 | 51.17 | 10.23 | 107.6 | 67.25 | 8.277 | 0.496 | 1.13 |

| C24 | 2681 | 1037 | 207.4 | 1597 | 706.4 | 86.29 | <.0001 | 0.60 |

| C24:1 | 796.8 | 276.5 | 55.3 | 1564 | 670.5 | 82.53 | <.0001 | 1.96 |

| C26 | 82.06 | 36.41 | 7.281 | 28.84 | 15.99 | 1.969 | <.0001 | 0.35 |

| C26:1 | 34.81 | 16.43 | 3.287 | 41.36 | 18.45 | 2.271 | 0.162 | 1.19 |

| Dihydro-C16 | 43.61 | 19.74 | 3.949 | 173 | 141.1 | 17.36 | <.0001 | 3.97 |

| Total | 4983 | 1659 | 331.9 | 6188 | 2010 | 245.6 | 0.005 | 1.24 |

Figure 3. Ceramide profile in serum of healthy controls and HLH patients.

Sphingolipids were measured sera (100 μL) from healthy volunteers (Ctl; control) and patients with HLH, as described in Methods. A) C16-ceramide, B) dihydro-C16-ceramide, C) C24-ceramide, and D) C26-ceramide, (n=25 for control, n=66 for HLH; 2-tailed, unpaired Mann-Whitney test; ***p<.001).

Analysis of individual sphingoid bases (Table IV) revealed dihydro-S1P was decreased similar to S1P, and that dihydro-Sph levels were not significantly elevated. Therefore, despite the absence of robust changes in total SM or total Cer, marked changes in individual SM and Cer species, as well as Sph and S1P, are evident in sera samples from patients with HLH. Taken together, these results demonstrate complex alterations in the sphingolipid metabolic network in HLH.

Table IV.

Serum Sphingoid Base Profile in Control and HLH Samples

| Control | HLH | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sphingoid Base | Mean (pmol/mL) | Std. Deviation | Std. Error | Mean (pmol/mL) | Std. Deviation | Std. Error | p-value | Fold-Change |

| Sph | 45.79 | 24.2 | 4.841 | 73.64 | 60.76 | 7.423 | 0.0436 | 1.61 |

| Dihydro-Sph | 64.67 | 37.89 | 7.579 | 69.1 | 52.09 | 6.412 | 0.8904 | 1.07 |

| S1P | 788.7 | 284 | 56.81 | 361.3 | 222.1 | 27.14 | <.0001 | 0.46 |

| Dihydro-S1P | 149.3 | 70.69 | 14.14 | 49.62 | 33.73 | 4.152 | <.0001 | 0.33 |

Relationship between C16-Ceramide and Sphingosine Balance and Survival in HLH

Given the presumed role of S-SMase as a pro-inflammatory mediator, we speculated that S-SMase activity might be of prognostic significance, and lower levels of S-SMase might suggest less systemic inflammation and a greater likelihood of survival. To test this hypothesis, we evaluated serum S-SMase activity in patients who survived and those who succumbed in spite of treatment (Fig. S2A, Table S3). S-SMase activity was elevated in all HLH patients (compared to control serum), and was not significantly different between the HLH patients who died and those who recovered, and therefore was not associated with survival in patients with HLH.

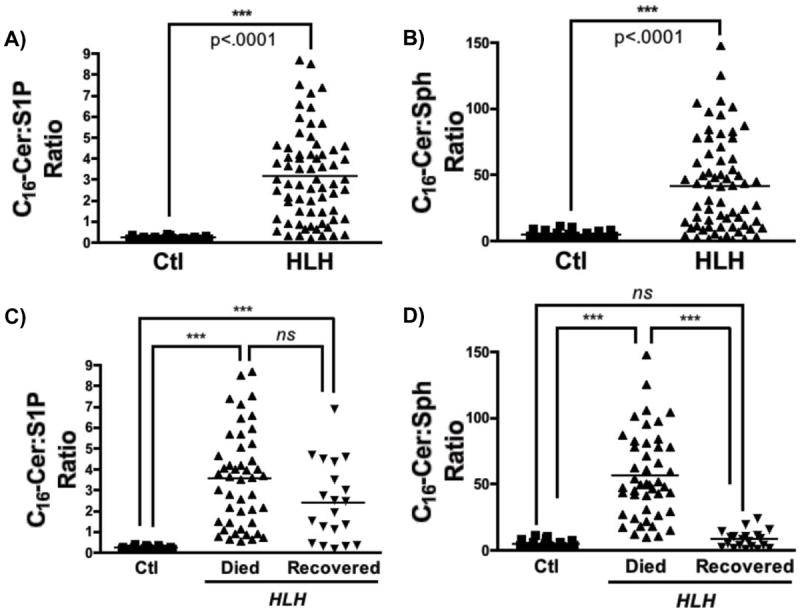

The ceramide produced by S-SMase can be metabolized to other bioactive sphingolipids such as sphingosine and S1P. Thus, although S-SMase activity showed no correlation with survival, we considered the possibility that the levels of downstream metabolites might have prognostic significance. Although increases in level of multiple ceramide species had been observed (Fig. 3, Table III), previous cell-based studies had established a strong relationship between S-SMase activity and the generation of C16-Cer in particular [23]. Moreover, elevations in C16-Cer showed the most robust alterations in patients with HLH than for other Cer analytes (5.25-fold over controls, see Table III). Accordingly, we evaluated serum levels of C16-Cer, Sph, and S1P in patients with HLH that died despite treatment, and those that recovered to determine if associated alterations in the serum sphingolipidomic profile predicted survival (Fig. S2B-D). In patients with HLH who died, C16-Cer levels remained elevated, while levels of Sph were unchanged, and levels of S1P were reduced. In contrast, HLH patients who recovered had lower levels of serum C16-Cer than those patients that died, and higher levels of Sph.

As the relative levels of these individual SPL analytes appeared to vary between HLH patients depending on the final clinical outcome, we evaluated the ratio of C16-Cer to S1P, and C16-Cer to Sph to quantify these differences. As would be expected based on the changes in the levels of the individual analytes, the ratio of C16-Cer:S1P and of C16-Cer:Sph were both significantly elevated in HLH patients (Fig. 4A-B). Subgroup analysis of the HLH patients that died compared to those that recovered demonstrated that the ratio of C16-Cer:Sph, but not C16-Cer:S1P, was uniquely elevated in HLH patients that died in spite of treatment (Fig. 4C-D). Strikingly, the ratio of C16-Cer:Sph in HLH patients that recovered was dramatically reduced compared to those that died, and was comparable to the ratio of C16-Cer:Sph in healthy controls. These results demonstrate dramatic differences in the serum C16-Cer:Sph ratio in patients with HLH that died compared to those that recovered, and suggest that the balance between C16-Cer and Sph may be of prognostic significance in patients with HLH.

Figure 4. C16-ceramide:sphingoid base ratio and survival in HLH.

A-B) Ratios of C16-Cer:S1P and C16-Cer:Sph were plotted for healthy volunteers (Ctl) and HLH patients (HLH) C-D) Ratios of C16-Cer:S1P and C16-Cer:Sph for healthy volunteers (Ctl), HLH patients that did passed away despite aggressive therapy (HLH-Died), and HLH patients that recovered following treatment (HLH-Recovered). Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s post-test analysis; ns – not statistically significant, **p<.01, ***p<.001). Note, that C16-Cer was evaluated (and not other Cer species) as levels of C16-Cer exhibited the greatest fold-change (see Table III).

DISCUSSION

In this study we performed the first targeted metabolomic screening study in patients with HLH focusing on the serum sphingolipidome. We focused on the serum sphingolipidomic profile building on a previous study demonstrating upregulation of S-SMase in HLH [28] and the well-established role for various sphingolipids in inflammation [33]. The data presented here demonstrate upregulation of serum S-SMase activity in primary and secondary HLH, with robust and novel alterations in the serum sphingolipidomic profile of affected patients. Furthermore, analysis of relative levels of SPLs demonstrated a strong association between the ratio of C16-Cer:Sph and survival of HLH patients. Collectively, these results demonstrate a novel association between serum SPLs and HLH, and suggest that (1) measurement of serum SPLs may be of prognostic value in assessing HLH patients, and (2) modulation of pro-inflammatory SPL metabolism may represent a target for future investigation and possible therapeutic intervention in HLH. However, further investigation of the metabolic and biologic consequences of upregulation of the S-SMase/Cer pathway will be required to elucidate the significance of serum SPL alterations in HLH, as well as other systemic inflammatory conditions.

Regulation, Origin, and Fate of Serum S-SMase

Upregulation of S-SMase by inflammatory cytokines is well established, and elevated levels of serum S-SMase have been described in several human disease states, including sepsis, diabetes, and cachectic heart failure [25-27]. Once secreted, the active enzyme encounters SM in a variety of settings and is positioned to interact with soluble lipoprotein-bound SM in serum, SM in the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane of endothelial cells, as well as SM associated with formed elements of blood.

Endothelial cells are known to be abundant sources of S-SMase [22], and are known to secrete both apically and basolaterally. Apical secretion of S-SMase from endothelial cells is considered a primary contributor to total serum S-SMase, although this has yet to be confirmed using genetic models (e.g. conditional endothelial-specific aSMase -/- mice). The cell type(s) of origin for serum S-SMase in HLH and other inflammatory conditions remains unclear. S-SMase can be released from lymphocytes, monocytes/macrophages, platelets, and endothelial cells, all of which may contribute to serum S-SMase levels [34].

Following resolution of inflammation or successful response to treatment, S-SMase levels appear to normalize (data not shown). Three possible scenarios for enhanced clearance include: 1) directed degradation by extracellular proteases (regulated vs. constitutive), 2) endocytosis by tissues (e.g. liver, lung), and 3) excretion in the urine. It is known that large amounts of S-SMase are detected in the urine of patients with sepsis, and one of the earliest preparations of aSMase used for biochemical analysis was from large volumes of human urine [35]. The mechanism of downregulation of S-SMase will require further investigation, but may involve any combination of the scenarios discussed above. Improved understanding of the regulation of S-SMase may permit more selective targeting of agents to disrupt the S-SMase/Cer pathway.

Metabolic role of S-SMase in HLH

Based on the findings presented above, we conclude that increased serum S-SMase activity in patients with HLH is associated with significant alterations of the serum sphingolipidomic profile (e.g. ↑C16-Cer, ↑Sph, ↓S1P). Two important conclusions can be made from these findings. First, generation of Sph implies that action of a ceramidase (CDase) to deacylate Cer to form Sph. This means that an extracellular CDase may be similarly regulated in HLH, or at least well positioned to act on Cer generated by the increased activity of S-SMase. The two likely candidates for such an action are acid CDase (ASAH1) and neutral CDase (ASAH2). Of note, aCDase is known to co-purify with aSMase [36], and the concerted action of aSMase and aCDase has been shown to promote a significant inflammatory response in cell culture studies [37]. And considering the relationship between the C16-Cer:Sph ratio and survival, the action of CDase to decrease Cer and increase Sph is likely to be of clinical significance. Furthermore, agents that induce aCDase and/or nCDase may be attractive options to decrease C16-Cer levels and increase Sph production.

Secondly, the finding that serum S1P levels are diminished in HLH suggests that the action of sphingosine kinase is impaired, or that degradation or clearance of S1P is enhanced. This was particularly unexpected given the established pro-inflammatory roles for S1P [14]. Regardless of the mechanism, the impact of diminished levels of serum S1P is likely of great pathophysiologic importance. For example, a central function of blood S1P is to provide a gradient for the egress of cells from the bone marrow [38]. Lower serum or blood S1P may disrupt this gradient, resulting in impaired trafficking of maturing cells into circulation and worsening cytopenias.

Biological role of the S-SMase/Ceramide pathway

While systemic upregulation of inflammatory cytokines is known to promote the elaboration of serum S-SMase, the biological role of the S-SMase/Cer pathway in sera remains unknown. Acid SMase has been shown to be important for IFN-γ elaboration from T-lymphocytes [39], release of IL-1β from microglia [40], and IL-2 secretion from CD4+ splenocytes [41]. Additionally, our lab has demonstrated a role for S-SMase in cellular sphingolipid metabolism [23] and identified a novel role for S-SMase in chemokine elaboration, specifically the chemokine CCL5, formerly known as RANTES [42]. CCL5 is potent chemoattract and T-lymphocytes activating molecule that has been implicated in a variety of physiologic and pathophysiologic processes, including coronary artery disease, HIV infection, and metastasis [43]. Additionally, elevated levels of serum CCL5 have been described for both perforin-deficient and Rab27a-deficient mice [44, 45] both models of primary HLH.

Given these connections, we evaluated serum levels of CCL5 in select patients from our HLH cohort. Surprisingly, CCL5/RANTES levels were decreased in a sampling from this patient population (Fig. S3A). Analysis of laboratory data following unblinding revealed that serum CCL5 levels trended downward in individuals over the course of hospitalization. Serum CCL5 is known to arise from platelets [46], and given the thrombocytopenia seen in HLH it is likely that this decrease in the chemokine CCL5 is secondary to decreased platelet mass (Fig. S3B). As aSMase is involved in transcriptional upregulation of CCL5 in epithelial cells and fibroblasts, post-translational regulation (i.e. regulation of secretion) of CCL5 may be aSMase-independent. Whatever the reason, the precise biological function of the S-SMase/Cer pathway in HLH and other inflammatory conditions remains unclear. Given the diversity of cytokines/chemokines that can be influences by aSMase, additional screening will be required to elucidate the biological role of the serum S-SMase/Cer pathway in HLH.

Clinical significance of upregulation of the S-SMase/Ceramide pathway in HLH

Given that S-SMase is upregulated in both acquired and congenital HLH, the S-SMase/Cer pathway – and associated alterations in the serum sphingolipidome – may have diagnostic and prognostic utility. The ratio of C16-Cer:Sph was uniquely elevated in HLH patients that died despite treatment, while it remained near control levels in the seven patients that survived (see Fig. 4D). Of note, this difference remained statistically significant with removal of the primary HLH patients (data not shown), who all survived. Taken together, these findings suggest that the metabolic balance of C16-Cer (presumably generated by S-SMase) relative to Sph is of particular prognostic importance in HLH patients.

Based on previous studies linking upregulation of S-SMase to inflammatory processes, one can readily speculate that S-SMase driven alterations in the serum sphingolipidome promote pro-inflammatory processes, and that inhibition of this pathway might attenuate the pathologic immune response in HLH. However, the biological function of the serum S-SMase/Cer pathway remains unclear, and future studies will be required to elucidate the precise role of S-SMase-derived serum Cer in HLH pathophysiology. However, it is tempting to speculate that existing drugs such as the S1P receptor antagonist FTY720 (fingolimod), which possesses potent anti-inflammatory properties and is FDA approved for the treatment of remitting relapsing multiple sclerosis [47], or inhibitors of aSMase and/or aCDase that are currently being developed [48], may limit pathologic inflammatory responses in HLH and thereby improve survival.

Conclusion

HLH is increasingly recognized clinically, and is often fatal without treatment. Even with improved vigilance and improved treatment modalities, the mortality rate for HLH remains high. Consequently, improved understanding of the pathophysiology of cytokine-mediated pathobiology in HLH is likely to reveal novel targets for therapeutic intervention. Improved understanding of the roles and regulation of the S-SMase/Cer pathway is likely to provide insight into the pathophysiology of this often fatal syndrome.

Supplementary Material

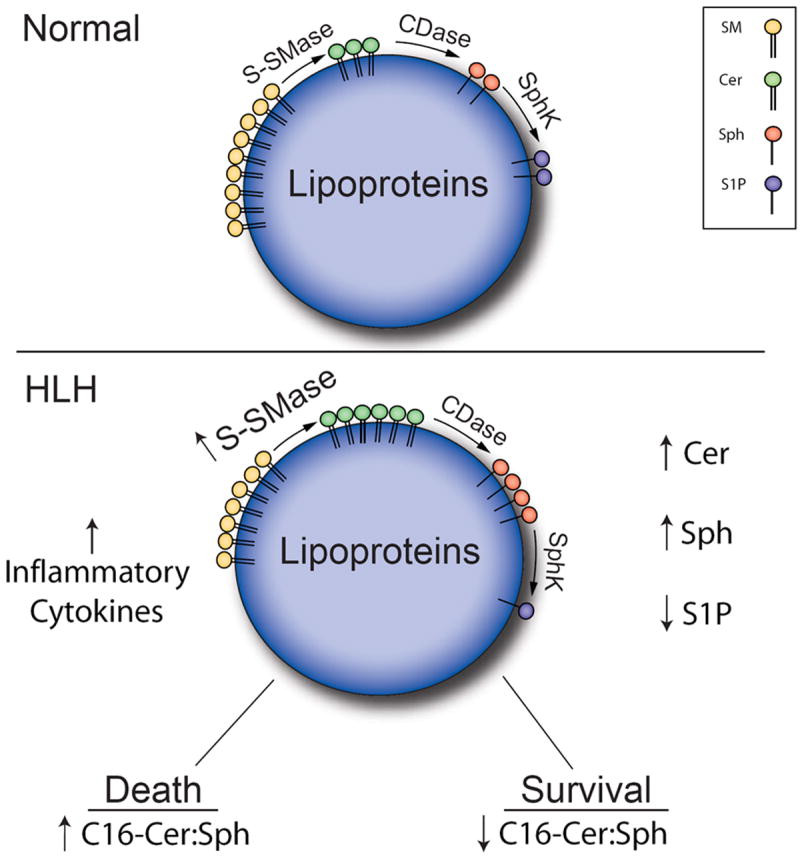

Figure 5. Schematic of S-SMase/ceramide pathway in HLH.

In HLH, dysregulation of the inflammatory response results in hypercytokinemia which in turn promotes upregulation of serum S-SMase. S-SMase is well positioned to act on serum SM (primarily bound to lipoproteins) driving production of select Cer species. Upon action of a downstream CDase, S-SMase-derived Cer can be deacylated to form Sph. Key changes in the serum SPL profile in patients with HLH, include elevations in total Cer and Sph, as well as decreased levels of S1P. C16-Cer levels exhibited the most significant increase in HLH. As described in Figure 7, the ratio of C16-Cer:Sph correlates very strongly with survival – HLH patients that died had higher serum levels of C16-Cer relative to Sph, whereas the ratio of C16-Cer:Sph was significantly lower HLH patients that survived.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to the MUSC Analytical Lipidomics Core (Dr. Jacek Bielawski, Barbara Rembiesa, Justin Snider, and Jason Pierce), the MUSC Synthetic Lipidomics Core (Dr. Alicja Bielawska, Nalini Mayroo).

This work was supported by NIH/NCI P01 CA097132 (Y.A.H.), American Heart Association Pre-Doctoral Fellowship (AHA 081509E – R.W.J.), NIH MSTP Training Grant (GM08716 – R.W.J.), MUSC Hollings Cancer Center Abney Foundation Scholarship (R.W.J.), SCE&G Scholarship (R.W.J.), and Ministerio de Educacion y Ciencia (Spain) Predoctoral Fellowship AP2006-02190 (F.S.)

Footnotes

Contribution: R.W.J., J.Lazarchick., M.S. and K.S. initiated the study, which was designed R.W.J., J.T.L., M.S., J.L. and K.S., with K.S. as principal investigator. R.W.J. performed the data analysis for this paper with support from J. Lazarchick.; and R.W.J. wrote the manuscript, which was finalized by Y.A.H., J. Lazarchick, and K.S. Sample preparation, collection, and experiments were performed by R.W.J., C.J.C, M.S., B.W., F.S., and J.M. All authors reviewed the paper and approved the final version.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Filipovich AH. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) and related disorders. Hematology / the Education Program of the American Society of Hematology American Society of Hematology Education Program. 2009:127–131. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2009.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta S, Weitzman S. Primary and secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: clinical features, pathogenesis and therapy. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2010;6:137–154. doi: 10.1586/eci.09.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Filipovich AH. The expanding spectrum of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;11:512–516. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e32834c22f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henter JI, Elinder G, Soder O, et al. Incidence in Sweden and clinical features of familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1991;80:428–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1991.tb11878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clementi R, Emmi L, Maccario R, et al. Adult onset and atypical presentation of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in siblings carrying PRF1 mutations. Blood. 2002;100:2266–2267. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nagafuji K, Nonami A, Kumano T, et al. Perforin gene mutations in adult-onset hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Haematologica. 2007;92:978–981. doi: 10.3324/haematol.11233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jordan MB, Allen CE, Weitzman S, et al. How I treat hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Blood. 2011;118:4041–4052. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-278127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perez N, Virelizier JL, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, et al. Impaired natural killer activity in lymphohistiocytosis syndrome. The Journal of pediatrics. 1984;104:569–573. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(84)80549-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raschke RA, Garcia-Orr R. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: a potentially underrecognized association with systemic inflammatory response syndrome, severe sepsis, and septic shock in adults. Chest. 2011;140:933–938. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janka GE. Familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. European journal of pediatrics. 1983;140:221–230. doi: 10.1007/BF00443367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trottestam H, Horne A, Arico M, et al. Chemoimmunotherapy for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: long-term results of the HLH-94 treatment protocol. Blood. 2011;118:4577–4584. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-356261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nishi M, Nishimura R, Suzuki N, et al. Reduced-intensity conditioning in unrelated donor cord blood transplantation for familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Am J Hematol. 2012;87:637–639. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hannun YA, Obeid LM. Principles of bioactive lipid signalling: lessons from sphingolipids. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:139–150. doi: 10.1038/nrm2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strub GM, Maceyka M, Hait NC, et al. Extracellular and intracellular actions of sphingosine-1-phosphate. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2010;688:141–155. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-6741-1_10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hammad SM. Blood sphingolipids in homeostasis and pathobiology. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2011;721:57–66. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-0650-1_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hojjati MR, Li Z, Zhou H, et al. Effect of myriocin on plasma sphingolipid metabolism and atherosclerosis in apoE-deficient mice. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:10284–10289. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412348200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sattler KJ, Elbasan S, Keul P, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate levels in plasma and HDL are altered in coronary artery disease. Basic Res Cardiol. 2010;105:821–832. doi: 10.1007/s00395-010-0112-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drobnik W, Liebisch G, Audebert FX, et al. Plasma ceramide and lysophosphatidylcholine inversely correlate with mortality in sepsis patients. Journal of lipid research. 2003;44:754–761. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M200401-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park TS, Panek RL, Rekhter MD, et al. Modulation of lipoprotein metabolism by inhibition of sphingomyelin synthesis in ApoE knockout mice. Atherosclerosis. 2006;189:264–272. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Milhas D, Clarke CJ, Hannun YA. Sphingomyelin metabolism at the plasma membrane: implications for bioactive sphingolipids. FEBS letters. 2010;584:1887–1894. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.10.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schuchman EH. The pathogenesis and treatment of acid sphingomyelinase-deficient Niemann-Pick disease. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2009;47(Suppl 1):S48–57. doi: 10.5414/cpp47048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marathe S, Schissel SL, Yellin MJ, et al. Human vascular endothelial cells are a rich and regulatable source of secretory sphingomyelinase. Implications for early atherogenesis and ceramide-mediated cell signaling. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:4081–4088. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.7.4081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jenkins RW, Canals D, Idkowiak-Baldys J, et al. Regulated secretion of acid sphingomyelinase: implications for selectivity of ceramide formation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010;285:35706–35718. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.125609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wong ML, Xie B, Beatini N, et al. Acute systemic inflammation up-regulates secretory sphingomyelinase in vivo: a possible link between inflammatory cytokines and atherogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:8681–8686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.150098097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Claus RA, Bunck AC, Bockmeyer CL, et al. Role of increased sphingomyelinase activity in apoptosis and organ failure of patients with severe sepsis. FASEB J. 2005;19:1719–1721. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2842fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doehner W, Bunck AC, Rauchhaus M, et al. Secretory sphingomyelinase is upregulated in chronic heart failure: a second messenger system of immune activation relates to body composition, muscular functional capacity, and peripheral blood flow. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:821–828. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gorska M, Baranczuk E, Dobrzyn A. Secretory Zn2+-dependent sphingomyelinase activity in the serum of patients with type 2 diabetes is elevated. Horm Metab Res. 2003;35:506–507. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-41810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takahashi T, Abe T, Sato T, et al. Elevated sphingomyelinase and hypercytokinemia in hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2002;24:401–404. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200206000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Henter JI, Horne A, Arico M, et al. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48:124–131. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bielawski J, Szulc ZM, Hannun YA, et al. Simultaneous quantitative analysis of bioactive sphingolipids by high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Methods. 2006;39:82–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liebisch G, Vizcaino JA, Kofeler H, et al. Shorthand notation for lipid structures derived from mass spectrometry. Journal of lipid research. 2013;54:1523–1530. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M033506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hannun YA, Obeid LM. Many ceramides. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2011;286:27855–27862. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R111.254359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nixon GF. Sphingolipids in inflammation: pathological implications and potential therapeutic targets. British journal of pharmacology. 2009;158:982–993. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00281.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jenkins RW, Canals D, Hannun YA. Roles and regulation of secretory and lysosomal acid sphingomyelinase. Cell Signal. 2009;21:836–846. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Quintern LE, Sandhoff K. Human acid sphingomyelinase from human urine. Methods Enzymol. 1991;197:536–540. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)97180-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.He X, Okino N, Dhami R, et al. Purification and characterization of recombinant, human acid ceramidase. Catalytic reactions and interactions with acid sphingomyelinase. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:32978–32986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301936200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jenkins RW, Clarke CJ, Canals D, et al. Regulation of CC ligand 5/RANTES by acid sphingomyelinase and acid ceramidase. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2011;286:13292–13303. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.163378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Golan K, Vagima Y, Ludin A, et al. S1P promotes murine progenitor cell egress and mobilization via S1P1 mediated ROS signaling and SDF-1 release. Blood. 2012 doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-358614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Herz J, Pardo J, Kashkar H, et al. Acid sphingomyelinase is a key regulator of cytotoxic granule secretion by primary T lymphocytes. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:761–768. doi: 10.1038/ni.1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bianco F, Perrotta C, Novellino L, et al. Acid sphingomyelinase activity triggers microparticle release from glial cells. EMBO J. 2009;28:1043–1054. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tischner D, Theiss J, Karabinskaya A, et al. Acid sphingomyelinase is required for protection of effector memory T cells against glucocorticoid-induced cell death. Journal of immunology. 2011;187:4509–4516. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jenkins RW, Clarke CJ, Canals D, et al. Regulation of CC Ligand 5/RANTES by Acid Sphingomyelinase and Acid Ceramidase. J Biol Chem. 286:13292–13303. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.163378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Levy JA. The unexpected pleiotropic activities of RANTES. J Immunol. 2009;182:3945–3946. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0990015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pachlopnik Schmid J, Ho CH, Chretien F, et al. Neutralization of IFNgamma defeats haemophagocytosis in LCMV-infected perforin- and Rab27a-deficient mice. EMBO Mol Med. 2009;1:112–124. doi: 10.1002/emmm.200900009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pachlopnik Schmid J, Ho CH, Diana J, et al. A Griscelli syndrome type 2 murine model of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:3219–3225. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kameyoshi Y, Dorschner A, Mallet AI, et al. Cytokine RANTES released by thrombin-stimulated platelets is a potent attractant for human eosinophils. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1992;176:587–592. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.2.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kappos L, Antel J, Comi G, et al. Oral fingolimod (FTY720) for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1124–1140. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Canals D, Perry DM, Jenkins RW, et al. Drug targeting of sphingolipid metabolism: sphingomyelinases and ceramidases. British journal of pharmacology. 2011;163:694–712. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01279.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.