Abstract

As genome sequencing technologies increasingly enter medical practice, genetics laboratories must communicate sequencing results effectively to non-geneticist physicians. We describe the design and delivery of a clinical genome sequencing report, including a one-page summary suitable for interpretation by primary care physicians. To illustrate our preliminary experience with this report, we summarize the genomic findings from ten healthy patient participants in a study of genome sequencing in primary care.

Keywords: whole genome sequencing, genomic screening, laboratory reporting, molecular testing

The clinical implementation of genomic medicine has begun and is widely anticipated to bring exciting medical benefits. Whole exome and whole genome sequencing, hereafter referred to as genomic sequencing (GS), is becoming increasingly useful in the diagnosis and treatment of rare diseases[1–3] and cancer[4–6] and is currently used predominantly by genetics specialists or sub-specialty practitioners[1]. In anticipation of the more widespread introduction of clinical sequencing to general medicine practice, we are conducting a randomized clinical trial studying the impact of GS, with attendant incidental findings, in both the specialty care of a hereditary illness and the primary care of healthy adults. In order to study the impact of GS and its clinical outcomes in this context, we have refined an interpretive pipeline for filtration and analysis of any medically relevant variants discovered in an individual genome[7] and designed a report to communicate these results effectively to non-geneticist physicians. Here we describe this report and our early experiences delivering GS results to primary care physician participants via a Genome Report (Figure and Appendix), along with the genomic results from the first ten healthy patient participants.

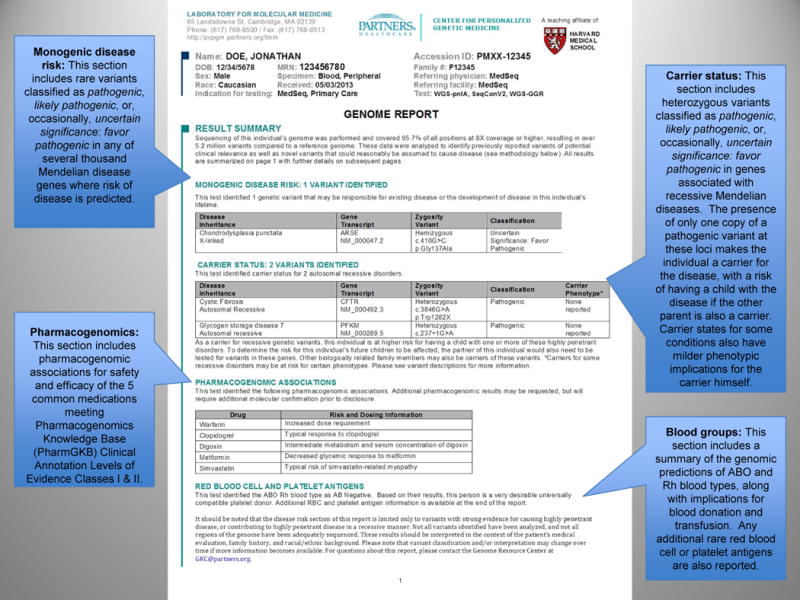

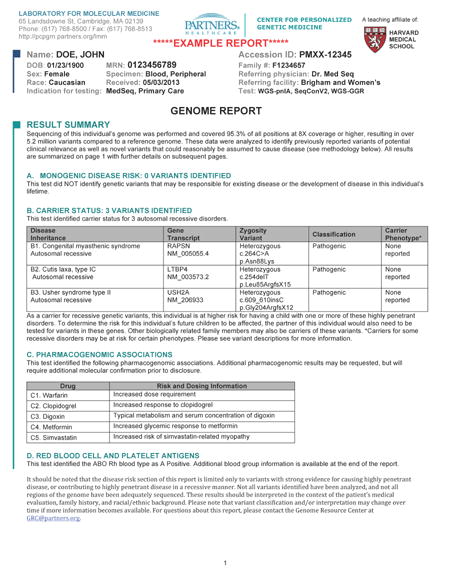

Figure.

Summary page of the Genome Report for genomic sequencing results for a generally healthy individual

The Challenge of Genomic Screening in Healthy Individuals

GS of individuals without a suspected genetic illness is not currently recommended[8] but may eventually be utilized in population-based genomic screening for the practice of preventive medicine[9,10]. Under this model, knowledge gained from GS might guide heightened surveillance in the face of increased genetic predisposition, reveal pharmacogenomic information that could maximize drug efficacy and minimize adverse effects, or be used for reproductive planning. As one of the NIH-funded centers in the Clinical Sequencing Exploratory Research Consortium[11], we are conducting the MedSeq Project to develop such processes and to explore the risks and benefits of sequencing healthy adults[12]. A significant challenge for genomic screening with GS is to identify, distill, and report the variants that have clinical significance for a healthy individual.

Molecular laboratories have developed standards and ontologies for analyzing and communicating the clinical significance of genetic variants found during GS of individuals with a suspected genetic disease[13,14]. After automated filtration and manual curation, geneticists reporting on genome sequencing may convey a variant’s clinical significance by using a variant classification schema such as benign, likely benign, variant of uncertain significance (VUS), likely pathogenic, or pathogenic. Because many variants fall into the uncertain category, some laboratories will further sub-classify VUS into subcategories such as favor benign or favor pathogenic. While efforts at standardization are underway, there is as yet limited consensus on the validity and evidence for pathogenicity that a variant should have before being reported to physicians and patients. If a laboratory identifies a VUS in a gene related to the reason for clinical sequencing, it will likely choose to report that finding to the ordering physician, despite the inherent uncertainties. For example, a VUS in the cardiac β-myosin heavy chain (MYH7) gene will likely be reported when the patient has familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

But when sequencing is performed in healthy individuals without a specific reason for genomic testing, the scenario more closely resembles screening tests used in preventive medicine, which are generally held to higher standards of validity and utility. For example, one might argue that a VUS in the MYH7 gene should be reported to the patient with familial cardiomyopathy, because additional testing might determine if the variant segregates with disease in the family. By contrast, whether this variant should be reported to the generally healthy individual without a personal or familial history of cardiomyopathy is a much more difficult question, absent studies with long-term follow-up that can help elucidate the pathogenicity of the variant, as well as the penetrance of pathogenic variants in an unselected population.

Interpreting Genome Sequencing Results of Healthy Individuals

As part of the MedSeq Project, we are performing GS in patients who have been identified by their primary care physicians as having no major medical conditions. We are communicating the results of GS to non-geneticist physicians recruited from the primary care practices at our academic medical center, despite the challenges of interpreting and reporting identified variants and the concerns that the primary care workforce may not be prepared for the clinical integration of genomic information[15–18]. For each participant, whole genome sequencing is performed in a CLIA-approved laboratory and the resulting raw files of annotated high-quality variants are filtered based on their allele frequencies, previous disease associations in reference databases, genic locations, and predicted functional impacts. Variants are then manually classified by a review of genetic and functional evidence from the scientific literature as previously described[7]. At the end of this pipeline, the Genome Report for generally healthy individuals includes variants classified as likely pathogenic, pathogenic, or VUS sub-classified as favor pathogenic. In cases of uncertainty in how best to weight evidence for variant classification, the larger study team discusses the evidence as a group, careful to adhere to this systematic approach for variant classification and returning results. In this study, the laboratory interprets the GS data and issues the Genome Reports without any clinical knowledge about the patient. Given the low pretest probability of disease among healthy individuals, we do not report the vast majority of VUSs and none of the benign or likely benign variants. By reporting variants with at least some degree of evidence favoring pathogenicity, we aim to strike a balance between the risks of returning uncertain results and the potential clinical benefits for the generally healthy person undergoing genomic screening.

Communicating Genome Sequencing Results to Physicians

The molecular and clinical geneticists, genetic counselors, bioinformaticians, clinicians, and social scientists comprising the study team have been guided by two main principles in designing our Genome Report for healthy individuals. First, although genomic information has been heralded as a disruptive technology, we envision that its successful integration into medical practice will conform to standard clinical workflows, through providers to patients. The molecular laboratory sends the Genome Report, via the electronic health record, to the ordering physician. The report is written in medical terminology and not at a lay patient level, thus representing a different paradigm than direct-to-consumer genomics products. A second guiding principle is that GS reports must relay the most important findings concisely to busy physicians, but brevity must not mask complexity when it is present. The reports must be complete while still conveying a sense of prioritization, so that overwhelming amounts of test information and clinically uncertain results do not distract from the results in each report that may be most clinically significant for the patient. These guiding principles allow us to incorporate feedback flexibly to improve the Genome Report. For example, we eliminated the word “Mendelian” from an earlier version of the report after non-geneticist physicians reported uncertainty in its meaning.

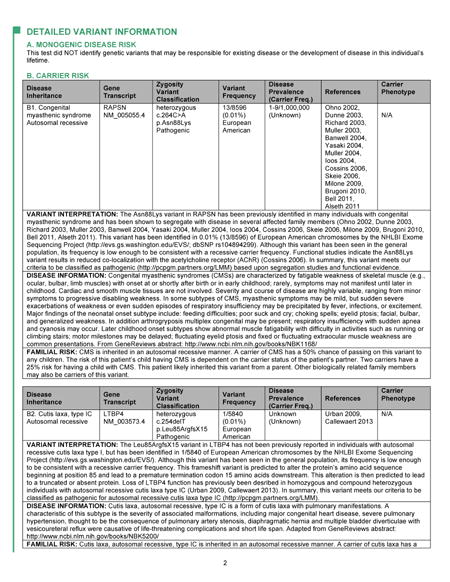

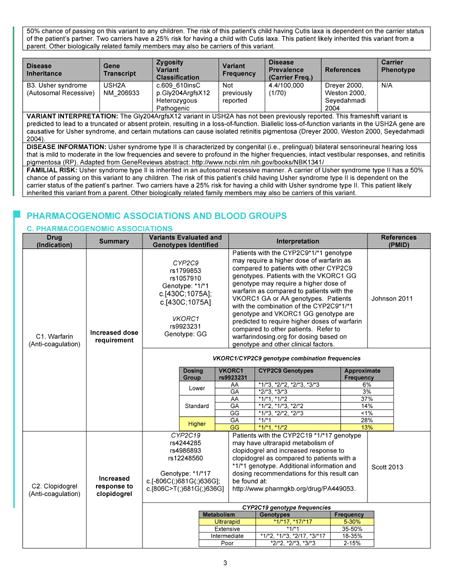

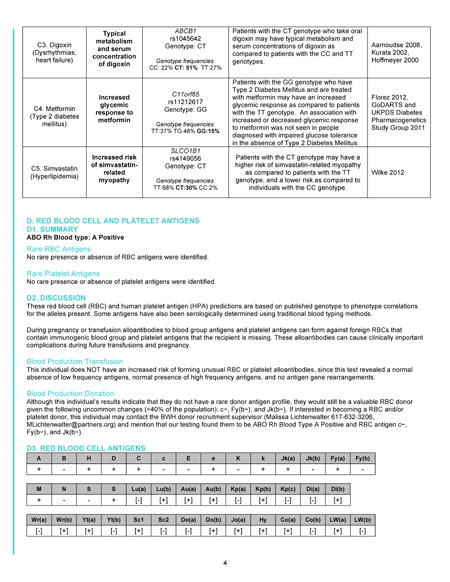

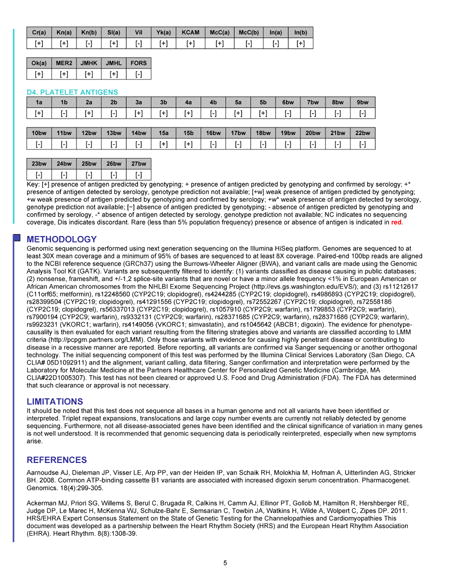

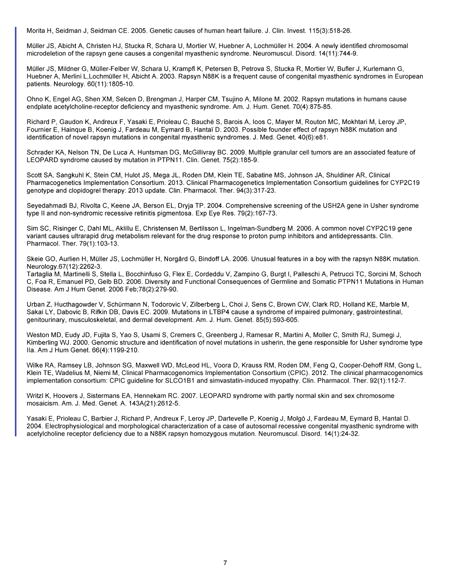

The first page of the Genome Report (Figure) is a summary of the key findings from the GS, while subsequent pages give more detailed information. This format mirrors the precedent of prioritized information seen in other clinical reports. For example, a radiologist’s full text of a chest X-ray report may describe in detail the radiographic appearance of the lungs, cardiac silhouette, ribs, vertebrae, and overlying soft tissue. However, the Impression section of the report, often set apart as separate text with bold lettering, might simply state “No acute cardiopulmonary process” or “Right middle lobe pneumonia”. The receiving physician often looks here first and then uses clinical judgment to determine whether the details in the full text of the report warrant further consideration. In our Genome Report, the first page is the genomic Impression, summarizing the identified variants that may cause monogenic disease or that indicate carrier status of autosomal recessive disorders. It also includes brief summaries of the implications of the patient’s genome for blood donation and transfusion[19] and for the safety and efficacy of five medications commonly used in primary care meeting Pharmacogenomics Knowledge Base (PharmGKB) Clinical Annotation Levels of Evidence Classes I and II criteria[20]: warfarin, clopidogrel, digoxin, metformin, and simvastatin. Subsequent pages of the Genome Report go on to define the precise variants identified and provide results and interpretation in greater detail (Appendix), including a discussion of the scientific evidence favoring or disfavoring pathogenicity for each variant, references to relevant studies, information about the associated diseases, and risk to family members. This section also gives greater detail about the pharmacogenomic and blood antigen loci interrogated in each genome, as well as the details and limitations of the sequencing and interpretation methodologies. Despite concerns that non-geneticist physicians are unprepared for genomic medicine[15–18], pilot testing among primary care physician participants of the MedSeq Project, suggests that the Genome Report communicates clinical sequencing results effectively. Many physicians expressed the idea that the information is initially daunting but ultimately manageable, represented by one who stated, “Although at first glance it is intimidating, I think if you get used to it, you probably can handle this.”

Although we have designed the Genome Report with clarity in mind, we do not assume that it alone is sufficient to turn primary care physicians into proficient genomic medicine practitioners. Primary care physician participants of the MedSeq Project first underwent an orientation to genomics concepts, including inheritance patterns and pharmacogenomics, and to the format of the Genome Report. Comprised of two one-hour in-person group classes and four hours of self-paced online modules, these sessions are comparable in length to other continuing medical education (CME) opportunities that are a part of routine physicians recertification. We also provide individualized support to physician participants during the course of the study by offering the option to contact study-affiliated medical geneticists and genetic counselors for assistance in interpreting and managing their patients’ GS results. We think this model of physician training and support will be scalable for an era when the genomics workforce will be insufficient to meet clinical demand[21], and as part of our research, we are collecting data on the use of these resources.

Sequences from the First Ten Healthy Patients

The Table shows the GS results reported for the first ten primary care patient participants. A total of 211 unique variants were assessed and classified. After assessment, 70 (33%) of these were classified as benign or likely benign, 116 (55%) as VUS, and 25 (12%) as likely pathogenic or pathogenic. We have reported three variants associated with monogenic disease risk in three healthy participants. The first of these was a variant in the arylsulfatase E (ARSE) gene (Figure and Table), observed previously in two males with chondrodysplasia punctata, an X-linked disorder of bone and cartilage development. Additionally, prior research indicated that the variant deleteriously impacted protein function. The same variant was identified in a male family member without the disease, though penetrance is known to be incomplete for the disorder. Given this limited scientific evidence, we classified and reported the ARSE variant as a VUS, favor pathogenic. For a generally healthy adult, the clinical significance of this variant is unknown, but by virtue of its appearance on the Genome Report, the primary care clinician has the opportunity to review the patient’s history and physical exam, and to ask more directed questions about other family members. Most variants reported in our healthy patients are associated with a carrier state for an autosomal recessive condition (Table). These carrier states may be associated with milder phenotypic implications for the carriers themselves, which we include in the Genome Report. For example, in one individual we reported a pathogenic variant in the WFS1 gene associated with Wolfram syndrome, a recessive neurodegenerative disease characterized by sensorineural deafness, type 1 diabetes mellitus, and pituitary gland dysfunction. However, carriers of WFS1 variants may themselves demonstrate some degree of low frequency hearing loss and impaired glucose metabolism. Although most patients have had at least one carrier variant, we are finding that primary care physicians and their healthy patients understand the extremely low likelihood that these carrier states will impact the health of patients and their family members.

Table.

Genomic sequencing results reported for the first ten generally healthy participants in the MedSeq Project.

| Section of Genome Report | Results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Monogenic disease risk | 3 variants identified in 3 patients | |||

|

| ||||

| Gene | Disease | Classification | ||

| LHX4 | Combined pituitary hormone deficiency | Pathogenic | ||

| KCNQ1 | Romano-Ward syndrome (a long QT syndrome) | Likely pathogenic | ||

| ARSE | Chondrodysplasia punctata | VUS: Favor pathogenic | ||

|

| ||||

| Carrier risk | 22 variants identified in 10 patients | |||

|

| ||||

| Gene | Disease | Classification | ||

| MMACHC | Methylmalonic aciduria and homocystinuria, cblC type | Pathogenic | ||

| CFTR | Cystic fibrosis | Pathogenic | ||

| PFKM | Glycogen storage disease 7 | Pathogenic | ||

| CUBN | Imerslund-Gräsbeck syndrome | Pathogenic | ||

| DUOX2 | Hypothyroidism | Pathogenic | ||

| ABCA4 | Stargardt disease | Pathogenic | ||

| MPO | Myeloperoxidase deficiency | Pathogenic | ||

| BTD | Biotinidase deficiency | Pathogenic | ||

| PYGL | Glycogen storage disease 6 | Pathogenic | ||

| SPG7 | Spastic paraplegia type 7 | Pathogenic | ||

| WFS1 | Wolfram syndrome | Pathogenic | ||

| CLRN1 | Usher syndrome type III | Pathogenic | ||

| CYP1B1 | Primary congenital glaucoma | Pathogenic | ||

| NLRP7 | Recurrent hydatidiform mole | Pathogenic | ||

| SPATA7 | Leber congenital amaurosis | Likely pathogenic | ||

| ERCC5 | Xeroderma pigmentosum | Likely pathogenic | ||

| COL7A 1 | Epidermolysis bullosa dystrophica | Likely pathogenic | ||

| KCNQ1 | Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome | Likely pathogenic | ||

| NAGA | Alpha-N-acetylgalactosidaminidase deficiency | Likely pathogenic | ||

| SP110 | Hepatic veno-occlusive disease with immunodeficiency | Likely pathogenic | ||

| RAB27A | Familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis | VUS: Favor pathogenic | ||

| CNGA3 | Achromatopsia | VUS: Favor pathogenic | ||

|

| ||||

| Pharmacogenomics | ||||

|

| ||||

| Warfarin |

2 patients with

decreased predicted dose requirement 3 patients with increased predicted dose requirement |

|||

|

| ||||

| Clopidogrel | 2 patients with increased predicted anti-platelet response | |||

|

| ||||

| Digoxin |

4 patients with

increased predicted serum drug

concentration 1 patient with decreased predicted serum drug concentration |

|||

|

| ||||

| Metformin | 5 patients with decreased predicted glycemic response | |||

|

| ||||

| Simvastatin | 2 patients with increased risk of medication-related myopathy | |||

|

| ||||

| Blood groups | 3 patients predicted to be desirable platelet donors | |||

VUS: Variant of uncertain significance.

The Future of the Genome Report

Our early experience in piloting the Genome Report has allowed us to optimize its format and content, including descriptive section header names understandable to primary care physicians and the appropriate distribution of details on the first versus the subsequent pages. More work remains, however. Communication today is instantaneous, and information is updated in real-time. Medical records, however, have generally not kept pace with state-of-the-art standards for communicating, displaying, and accessing information. At the same time, clinical data are becoming more complex, and the communication of results will need to become more dynamic and prioritized, allowing the physician and patient to access, digest, and use the data to variable degrees over time. One can imagine GS reports that have more creative dashboards for the clinician, and that incorporate hyperlinks to greater detail or to external references, allowing a physician to narrow or expand the focus of interrogating a patient’s genome. With the discovery of new disease genes, mutations, and clinically meaningful gene-gene and gene-exposure interactions, the genome report will need to reflect that new dynamism of genomic data. While our Genome Report provides an accessible summary of complex results using current clinical laboratory reporting and medical practices, it must eventually be adaptable to accurately and concisely communicate the full medical content contained within the genome. We are currently producing the Genome Report using the GeneInsight software suite[22], which is linked to a genomic knowledgebase so that variant classifications remain up-to-date based on new scientific discovery. Through this process, the physician receives an alert message when a previously reported variant in a patient’s genome has been reclassified on the basis of new knowledge (for example, from VUS to likely pathogenic). One can also imagine a dynamic genome report that evolves to maintain relevance to the patient’s individual clinical context over his life course, prioritizing carrier status during reproductive years and highlighting other genomic variants when newly abnormal clinical tests, physical findings, and medications are recorded. An active area of research is the role patients’ preferences might play in shaping which GS results are reported and how. Regardless of the format that GS results take moving forward, physicians will need clear signposts to help them navigate their patients’ genomes.

Acknowledgments

We thank the physician participants and patient participants of the MedSeq Project.

Funding: Grants U01-HG006500, U41-HG006834, R01-HG005092 from the National Human Genome Research Institute and U19-HD077671 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, both of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Role of the funding source: NIH had no role in the study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; the writing of this report; or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Appendix: Full Genome Report

Footnotes

Author contributions

Conception and design: JLV, HLM, CAM, CES, DML, JBK, ISK, MFM, ALM, HLR, RCG, WJL

Analysis and interpretation of the data: JLV, HLM, CAM, JBK, HLR, RCG, WJL

Drafting of the article: JLV, HLM, HLR, RCG

Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content: JLV, HLM, CAM, CES, DML, JBK, ISK, MFM, ALM, HLR, RCG

Final approval of the article: JLV, HLM, CAM, CES, DML, JBK, ISK, MFM, ALM, HLR, RCG, WJL

Provision of study materials or patients: CAM, CES, DML, HLR, RCG

Statistical expertise: JLV, HLM, CAM, JBK, HLR, RCG

Obtaining of funding: CAM, CES, DML, ISK, MFM, ALM, HLR, RCG

Administrative, technical, or logistic support: JLV, HLM, DML

Collection and assembly of data: JLV, HLM, CAM, DML, JBK, HLR, RCG

JLV confirms that he had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Declaration of interests: JLV, HLM, CAM, CES, DL, JBK, HLR, and RCG are employed by Partners Healthcare, which is the sole owner of GeneInsight, LLC. The authors declare that they have no other conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Yang Y, Muzny DM, Reid JG, Bainbridge MN, Willis A, Ward PA, Braxton A, Beuten J, Xia F, Niu Z, Hardison M, Person R, Bekheirnia MR, Leduc MS, Kirby A, Pham P, Scull J, Wang M, Ding Y, Plon SE, Lupski JR, Beaudet AL, Gibbs RA, Eng CM. Clinical whole-exome sequencing for the diagnosis of mendelian disorders. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1502–1511. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1306555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacob HJ, Abrams K, Bick DP, Brodie K, Dimmock DP, Farrell M, Geurts J, Harris J, Helbling D, Joers BJ, Kliegman R, Kowalski G, Lazar J, Margolis DA, North P, Northup J, Roquemore-Goins A, Scharer G, Shimoyama M, Strong K, Taylor B, Tsaih SW, Tschannen MR, Veith RL, Wendt-Andrae J, Wilk B, Worthey EA. Genomics in clinical practice: Lessons from the front lines. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:194cm195. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Green RC, Biesecker LG. Diagnostic clinical genome and exome sequencing. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2418–2425. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1312543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Egan JB, Shi CX, Tembe W, Christoforides A, Kurdoglu A, Sinari S, Middha S, Asmann Y, Schmidt J, Braggio E, Keats JJ, Fonseca R, Bergsagel PL, Craig DW, Carpten JD, Stewart AK. Whole-genome sequencing of multiple myeloma from diagnosis to plasma cell leukemia reveals genomic initiating events, evolution, and clonal tides. Blood. 2012;120:1060–1066. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-01-405977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dawson SJ, Tsui DW, Murtaza M, Biggs H, Rueda OM, Chin SF, Dunning MJ, Gale D, Forshew T, Mahler-Araujo B, Rajan S, Humphray S, Becq J, Halsall D, Wallis M, Bentley D, Caldas C, Rosenfeld N. Analysis of circulating tumor DNA to monitor metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1199–1209. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1213261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alexandrov LB, Nik-Zainal S, Wedge DC, Aparicio SA, Behjati S, Biankin AV, Bignell GR, Bolli N, Borg A, Borresen-Dale AL, Boyault S, Burkhardt B, Butler AP, Caldas C, Davies HR, Desmedt C, Eils R, Eyfjord JE, Foekens JA, Greaves M, Hosoda F, Hutter B, Ilicic T, Imbeaud S, Imielinski M, Jager N, Jones DT, Jones D, Knappskog S, Kool M, Lakhani SR, Lopez-Otin C, Martin S, Munshi NC, Nakamura H, Northcott PA, Pajic M, Papaemmanuil E, Paradiso A, Pearson JV, Puente XS, Raine K, Ramakrishna M, Richardson AL, Richter J, Rosenstiel P, Schlesner M, Schumacher TN, Span PN, Teague JW, Totoki Y, Tutt AN, Valdes-Mas R, van Buuren MM, van ’t Veer L, Vincent-Salomon A, Waddell N, Yates LR, Zucman-Rossi J, Futreal PA, McDermott U, Lichter P, Meyerson M, Grimmond SM, Siebert R, Campo E, Shibata T, Pfister SM, Campbell PJ, Stratton MR. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature. 2013;500:415–421. doi: 10.1038/nature12477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duzkale H, Shen J, McLaughlin H, Alfares A, Kelly M, Pugh T, Funke B, Rehm H, Lebo M. A systematic approach to assessing the clinical significance of genetic variants. Clin Genet. 2013;84:453–463. doi: 10.1111/cge.12257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.ACMG Board of Directors. Points to consider in the clinical application of genomic sequencing. Genet Med. 2012;14:759–761. doi: 10.1038/gim.2012.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bowen MS, Kolor K, Dotson WD, Ned RM, Khoury MJ. Public health action in genomics is now needed beyond newborn screening. Public health genomics. 2012;15:327–334. doi: 10.1159/000341889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grosse SD, Rogowski WH, Ross LF, Cornel MC, Dondorp WJ, Khoury MJ. Population screening for genetic disorders in the 21st century: Evidence, economics, and ethics. Public health genomics. 2010;13:106–115. doi: 10.1159/000226594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berg JS, Amendola LM, Eng C, Van Allen E, Gray SW, Wagle N, Rehm HL, DeChene ET, Dulik MC, Hisama FM, Burke W, Spinner NB, Garraway L, Green RC, Plon S, Evans JP, Jarvik GP. Processes and preliminary outputs for identification of actionable genes as incidental findings in genomic sequence data in the clinical sequencing exploratory research consortium. Genet Med. 2013;15:860–867. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vassy JL, Lautenbach DM, McLaughlin HM, Kong SW, Christensen KD, Krier J, Kohane IS, Feuerman LZ, Blumenthal-Barby J, Roberts JS, Lehmann LS, Ho CY, Ubel PA, MacRae CA, Seidman CE, Murray MF, McGuire AL, Rehm HL, Green RC, for The MedSeq Project The medseq project: A randomized trial of integrating whole genome sequencing into clinical medicine. Trials. 2014;15:85. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richards CS, Bale S, Bellissimo DB, Das S, Grody WW, Hegde MR, Lyon E, Ward BE. Acmg recommendations for standards for interpretation and reporting of sequence variations: Revisions 2007. Genet Med. 2008;10:294–300. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31816b5cae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rehm HL, Bale SJ, Bayrak-Toydemir P, Berg JS, Brown KK, Deignan JL, Friez MJ, Funke BH, Hegde MR, Lyon E. Acmg clinical laboratory standards for next-generation sequencing. Genet Med. 2013;15:733–747. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nippert I, Harris HJ, Julian-Reynier C, Kristoffersson U, Ten Kate LP, Anionwu E, Benjamin C, Challen K, Schmidtke J, Nippert RP, Harris R. Confidence of primary care physicians in their ability to carry out basic medical genetic tasks-a European survey in five countries-part 1. J Community Genet. 2011;2:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s12687-010-0030-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Selkirk CG, Weissman SM, Anderson A, Hulick PJ. Physicians’ preparedness for integration of genomic and pharmacogenetic testing into practice within a major healthcare system. Genetic testing and molecular biomarkers. 2013;17:219–225. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2012.0165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Korf BR, Berry AB, Limson M, Marian AJ, Murray MF, O’Rourke PP, Passamani ER, Relling MV, Tooker J, Tsongalis GJ, Rodriguez LL. Framework for development of physician competencies in genomic medicine: Report of the competencies working group of the inter-society coordinating committee for physician education in genomics. Genet Med. 2014 doi: 10.1038/gim.2014.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haga SB, Burke W, Ginsburg GS, Mills R, Agans R. Primary care physicians’ knowledge of and experience with pharmacogenetic testing. Clin Genet. 2012;82:388–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2012.01908.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lane W, Leshchiner I, Boehler S, Uy J, Aguad M, Smeland-Wagman R, Green R, Rehm H, Kaufman R, Silberstein L, Project fTM Comprehensive blood group prediction using whole genome sequencing data from the medseq project [abstract]. Proceedings of the 63rd annual meeting of the American Society of Human Genetics; 22–26 October 2013; Boston, MA. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Whirl-Carrillo M, McDonagh EM, Hebert JM, Gong L, Sangkuhl K, Thorn CF, Altman RB, Klein TE. Pharmacogenomics knowledge for personalized medicine. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;92:414–417. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2012.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Korf BR, Ledbetter D, Murray MF. Report of the banbury summit meeting on the evolving role of the medical geneticist, february 12–14, 2006. Genet Med. 2008;10:502–507. doi: 10.1097/gim.0b013e31817701fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aronson SJ, Clark EH, Babb LJ, Baxter S, Farwell LM, Funke BH, Hernandez AL, Joshi VA, Lyon E, Parthum AR, Russell FJ, Varugheese M, Venman TC, Rehm HL. The geneinsight suite: A platform to support laboratory and provider use of DNA-based genetic testing. Hum Mutat. 2011;32:532–536. doi: 10.1002/humu.21470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]