Abstract

Background and objectives

Older adults with ESRD often receive care in skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) after an acute hospitalization; however, little is known about acute care use after SNF discharge to home.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

This study used Medicare claims for North and South Carolina to identify patients with ESRD who were discharged home from a SNF between January 1, 2010 and August 31, 2011. Nursing Home Compare data were used to ascertain SNF characteristics. The primary outcome was time from SNF discharge to first acute care use (hospitalization or emergency department visit) within 30 days. Cox proportional hazards models were used to identify patient and facility characteristics associated with the outcome.

Results

Among 1223 patients with ESRD discharged home from a SNF after an acute hospitalization, 531 (43%) had at least one rehospitalization or emergency department visit within 30 days. The median time to first acute care use was 37 days. Characteristics associated with a shorter time to acute care use were black race (hazard ratio [HR], 1.25; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.04 to 1.51), dual Medicare-Medicaid coverage (HR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.03 to 1.50), higher Charlson comorbidity score (HR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.12), number of hospitalizations during the 90 days before SNF admission (HR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.03 to 1.22), and index hospital discharge diagnoses of cellulitis, abscess, and/or skin ulcer (HR, 2.59; 95% CI, 1.36 to 4.45). Home health use after SNF discharge was associated with a lower rate of acute care use (HR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.59 to 0.87). There were no statistically significant associations between SNF characteristics and time to first acute care use.

Conclusions

Almost one in every two older adults with ESRD discharged home after a post–acute SNF stay used acute care services within 30 days of discharge. Strategies to reduce acute care utilization in these patients are needed.

Keywords: renal failure, nursing home, frail elderly

Introduction

Recent studies among older Medicare beneficiaries admitted to the hospital show that nearly 20% are rehospitalized within 30 days of discharge from hospital to home and that 12%–15% are hospitalized within 30 days of discharge from a skilled nursing facility (SNF) to home (1–3). With the Affordable Care Act’s Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, there is now growing interest in transitional care interventions to lower rehospitalizations. Transitional care interventions aim to optimize care coordination and patient and/or caregiver empowerment for continual management of multiple comorbid conditions upon patient transfer to home (or any location) (4,5). Often with a multidisciplinary approach, these interventions have been implemented in multiple care settings, including hospitals and SNFs, and designed for specific conditions (e.g., heart failure, stroke, or myocardial infarction) (6–10).

Older adults with ESRD have high rates of hospitalization for acute events (e.g., stroke, fracture, and infection) and are often discharged to SNFs for short-term rehabilitation and/or skilled nursing care (11,12). ESRD is associated with a 42% higher rate of rehospitalizations after hospital discharge to home (3), but little is known about patterns of acute care use among older adults with ESRD who are discharged home from SNFs. It is possible that older adults with ESRD might have a higher risk of acute care use after SNF discharge than those without ESRD due to their greater burden of comorbidity, progressive functional decline, and treatment burden (13–15). Alternatively, they may have a lower risk of acute care use as a result of their more frequent contact with healthcare providers in their dialysis centers, which ensures closer clinical follow-up. Understanding acute care use after SNF discharge in this population may highlight a growing need for and inform the development of ESRD-specific transitional care interventions. The purpose of this retrospective cohort study was to measure the frequency of acute care utilization after SNF discharge among older adults with ESRD and to identify patient and facility characteristics associated with acute care use within 30 days of SNF discharge.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

We conducted a subgroup analysis among patients with ESRD included in a larger observational study of older Medicare beneficiaries discharged home from SNFs in North and South Carolina between January 1, 2010, and August 31, 2011 (1). Medicare Part A and Part B claims for 2008–2011 were used to ascertain the characteristics of each patient in the year before SNF admission and to measure outcomes within 30 days after SNF discharge. SNF organizational characteristics were ascertained from Nursing Home (NH) Compare data for October 2010. This study was approved by the US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and was granted exemption from the Duke University Institutional Review Board.

Study Population

All patients in the cohort were Medicare beneficiaries residing in North or South Carolina who were transferred from a hospital to a SNF and then discharged from the SNF to home within 106 days of SNF admission. We used a limit of 106 days to identify patients with SNF stays primarily reimbursed by Medicare under its 100-day reimbursement policy, and 6 additional days were included to incorporate patients with discharge delays. Patients discharged to home were included if they received home health services; however, patients who received home hospice services were excluded because home hospice care might be expected to influence rates of acute care use (16). We used the Medicare denominator file to identify beneficiaries with ESRD based on the following criteria: (1) current reason for Medicare entitlement indicated as ESRD, (2) Medicare status code for ESRD, or (3) presence of a Medicare ESRD flag. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) age <65 years at the time of SNF admission, (2) incomplete Medicare Part A and Part B coverage during the study period, or (3) Medicare managed care coverage at any time during the study period. These exclusion criteria were applied by the parent study to select a cohort with homogeneous health insurance coverage (1).

Variables

The primary outcome was time to first acute care use—defined as hospitalization or emergency department (ED) visit without hospitalization—within 30 days after SNF discharge. Time to first acute care use was taken as the number of days from SNF discharge to first acute care use. Additional outcomes included receipt of acute care use in the first 24 hours after SNF discharge, time to first acute care use within 90 days after SNF discharge, and proportion of deaths within 30 and 90 days after SNF discharge.

Medicare claims for the year before SNF admission were used to ascertain patient study variables, which included age at SNF admission, sex, state of residence at the time of SNF admission (North or South Carolina), Medicare-Medicaid dual enrollment status (defined by presence of a state Medicaid payment toward a resident’s Medicare premium in at least 1 month during the year before SNF admission), and race. We included race as a study variable because racial disparities exist in both prevalence of ESRD and use of SNFs (17,18). Race as recorded in the Medicare denominator file was aggregated into three categories (white, black, and other) because <1% of the parent study’s cohort had race besides white or black (1). We also included number of hospitalizations within 90 days before SNF admission, comorbid conditions and Charlson comorbidity score based on International Classification of Diseases–Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes in inpatient Medicare claims (19), and principal discharge diagnoses for the hospitalization immediately preceding SNF admission reported as ICD-9 Surveillance Diagnosis Group (SDG) codes (Neoplasms [SDG codes 03–14], Cardiovascular [SDG codes 30, 31, and 37], Cerebrovascular [SDG code 40], Respiratory [SDG codes 44–49], Cellulitis, Abscess or Ulcer [SDG codes 72–73], Fractures [SDG codes 83–84], and Other [all remaining SDG codes]) instead of individual ICD-9 codes. We used Medicare claims during and after each patient’s SNF admission to ascertain length of SNF stay and use of home health services after discharge.

From NH Compare, we obtained information on the following SNF characteristics: facility bed count, ownership status (unknown, for-profit, government, or nonprofit), registered nurse hours per resident day, and licensed practical nurse hours per resident day (20).

Statistical Analyses

Patient and SNF study variables were reported as proportions for categorical variables and means with SDs or medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs) for continuous variables. Bivariate analyses were conducted to compare patient characteristics by presence of the primary outcome.

We used the Kaplan–Meier method to estimate the survival curve for time to first acute care use. Patients were censored at the time of death or at the end of the follow-up period (i.e., 30 days for the primary analysis, 90 days for the supplementary analyses). A Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to measure the adjusted association of all patient and SNF characteristics described above with time to first acute care use within 30 days of SNF discharge. Facilities missing variables from NH Compare (bed count [n=11], ownership status [n=11], and nursing hours [n=20]) were excluded from multivariate analyses. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS 9.2 software.

Results

Patient and Facility Characteristics

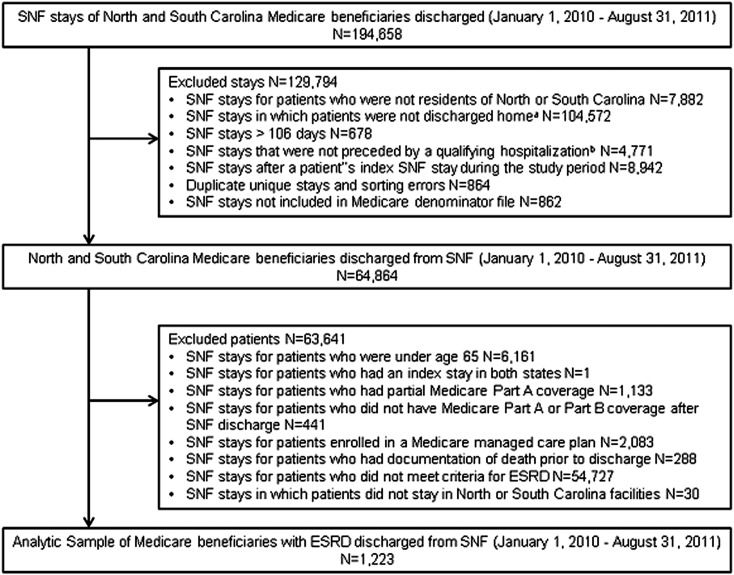

Our cohort was established from 194,658 stays by Medicare beneficiaries in North and South Carolina SNFs between January 1, 2010, and August 31, 2011 (Figure 1). As performed in the parent study (1), the following exclusions were applied: (1) SNF stays of patients who were not residents of North or South Carolina (n=7882) and not discharged home (n=104,572), (2) stays >106 days (n=678), (3) stays that were not preceded by an acute hospitalization (n=4771), (4) additional stays for patients who had >1 stay in the study period (n=8942), (5) duplicate stays or database sorting errors (n=864), and (6) stays that were not located in the Medicare denominator file (n=862). After identifying 64,864 unique patients, the following additional exclusions were applied in the parent study: (1) patients aged <65 years (n=6161), (2) patients with stays in both states (n=1), (3) patients who did not have full Medicare coverage or had Medicare managed care (n=3657), and (4) patients who died before discharge (n=228) (1). Of the 55,980 patients identified in the parent study (1), 54,727 patients did not meet criteria for ESRD and an additional 30 patients were excluded because the SNF was not in North or South Carolina. The remaining 1223 (2% of the parent study) patients were included in the analytic sample.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of cohort selection. aSNF stays included in the analysis were for patients discharged to home. Patients who were discharged to additional inpatient care (e.g., another SNF, long-term care facility, hospice facility, or hospital) were excluded from this cohort. bA qualifying hospitalization is defined as a hospitalization within 30 days before SNF admission that lasted at least 3 days. SNF, skilled nursing facility.

The average age was 75.0 years (SD 6.5), 9% of cohort members were aged ≥85 years, 46% were classified as black, and 36% were dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid (Table 1). Between January 1, 2010, and August 31, 2011, members of this cohort were discharged from 392 unique SNFs. Most facilities (65%) cared for two to nine unique cohort members with ESRD over the study period, whereas 121 (31%) cared for only one and 15 (4%) had >10 patients with ESRD. Almost half of the facilities (42%) had 101–150 beds, and 83% were for-profit facilities. Mean nursing hours per resident day were 0.73 hours (SD 0.71) for registered nurses and 0.91 (SD 0.31) for licensed practical nurses.

Table 1.

Characteristics of cohort by presence of acute care use within 30 days after SNF discharge

| Characteristic | Acute Care Use within 30 d (n=531) | No Acute Care Use within 30 d (n=692) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 74.9±6.4 | 75.1±6.6 | 0.72 |

| Men | 237 (44.6) | 309 (44.6) | 0.99 |

| Race | 0.01 | ||

| White | 254 (47.8) | 389 (56.2) | |

| Black | 270 (50.9) | 289 (41.8) | |

| Other | 7 (1.3) | 14 (2.0) | |

| State of residence | 0.18 | ||

| North Carolina | 353 (66.5) | 485 (70.1) | |

| South Carolina | 178 (33.5) | 207 (29.9) | |

| Dual Medicare-Medicaid coverage | 218 (41.1) | 220 (31.8) | <0.001 |

| ICD-9 Surveillance Diagnostic Groupa | 0.06 | ||

| Neoplasms | 8 (1.5) | 10 (1.5) | |

| Cardiovascular | 28 (5.3) | 22 (3.2) | |

| Cerebrovascular | 25 (4.7) | 20 (2.9) | |

| Respiratory | 43 (8.1) | 68 (9.8) | |

| Cellulitis, abscess, ulcer | 14 (2.6) | 7 (1.0) | |

| Fractures | 49 (9.2) | 67 (9.7) | |

| Other group | 364 (68.6) | 498 (71.9) | |

| Charlson comorbidity score | 4.6±1.8 | 4.3±1.8 | 0.001 |

| Hospitalizations before SNF stayb | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–1) | 0.002 |

| SNF length of stay (d) | 31.4±23.5 | 34.5±23.9 | 0.03 |

| Postdischarge characteristics | |||

| Home health use | 342 (64.4) | 494 (71.4) | 0.01 |

| Number of ED visits | 1.1 (1.4) | 0.35 (0.8) | <0.001 |

| Number of hospital admissions | 2.2 (1.3) | 0.6 (1.1) | <0.001 |

Data expressed as n (%), mean±SD, or median (interquartile range). Acute care use refers to composite outcome of ED use or hospitalization within 30 days after SNF discharge. Statistical significance between the groups was detected via the t test for continuous variables and the chi-squared test for dichotomous variables. SNF, skilled nursing facility; ICD-9, International Classification of Disease–Ninth Revision; ED, emergency department.

ICD-9 Surveillance Diagnostic Group is defined as the diagnostic group that includes the primary hospital discharge diagnosis for each patient.

Hospitalizations before SNF stay is defined as the number of hospitalizations in the 90 days before the index SNF stay.

Acute Care Use and Mortality after SNF Discharge

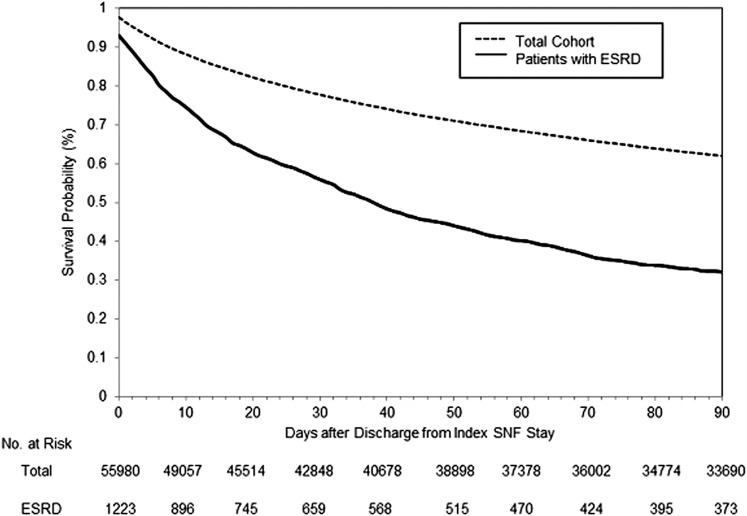

Within 30 days of SNF discharge, 531 patients (43%) had one or more acute care encounters consisting of a total of 392 hospital admissions and 252 ED visits without admission. The median time to first acute care use was 37 days (Figure 2). The incidence rate of acute care use after discharge decreased from 20.9 per 1000 patient-days within 30 days to 14.9 per 1000 patient-days within 90 days. Acute care use was documented for 7% of patients within 24 hours and 66% within 90 days of SNF discharge. Eight percent (n=99) of patients died within 30 days of SNF discharge and 18% (n=215) died within 90 days of SNF discharge.

Figure 2.

Survival curve of time to first acute care use. Plot showing the event-free survival of the total cohort of Medicare beneficiaries (previously published [1]) (dotted line) and the cohort of patients with ESRD (solid line) over 90 days after SNF discharge. Time to acute care use was defined as the number of days between the date of SNF discharge to the date of first acute care use. Acute care use refers to composite outcome of emergency department use or hospitalization within 30 days after SNF discharge.

Predictors of Acute Care Use after SNF Discharge

Compared with patients who did not receive acute care within 30 days of SNF discharge, those who did were more likely to be black (51% versus 42%; P=0.01), dually eligible (41% versus 32%; P<0.001), had higher Charlson comorbidity scores (mean 4.6 [SD 1.8] versus 4.3 [SD 1.8]; P=0.001), and had more hospital stays in the year before index SNF stay (median 1 day [IQR, 0–2] versus 1 [IQR, 0–1]; P=0.002) (Table 1). Hospital discharge diagnoses (ICD-9 SDGs) immediately preceding the index SNF stay did not differ for those with and without early acute care use. Length of stay in the SNF was significantly shorter among patients who used acute services within 30 days of discharge compared with those who did not (mean 31.4 days [SD 23.5] versus 34.5 [SD 23.9]; P=0.03). In addition, patients who used acute care services within 30 days of SNF discharge were less likely to have received home health services compared with those who did not (64% versus 71%; P=0.01).

In multivariable regression analysis, characteristics associated with a higher rate of acute care use within 30 days after SNF discharge were black race (hazard ratio [HR], 1.25; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.04 to 1.51), dual Medicare-Medicaid coverage (HR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.03 to 1.50), higher Charlson comorbidity score (HR, 1.07 per 1-point increase in Charlson score; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.12), and number of hospitalizations within 90 days before SNF admission (HR, 1.12 per hospital admission; 95% CI, 1.03 to 1.22) (Table 2). The rate of acute care use in patients with index hospital discharge diagnoses for cellulitis, abscesses, or chronic skin ulcers was more than twice the rate in patients with discharge diagnoses in the reference group (all other SDGs not listed in Table 2) (HR, 2.59; 95% CI, 1.36 to 4.45). By contrast, home health use after SNF discharge was associated with a lower rate of acute care use (HR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.59 to 0.87). None of the SNF characteristics (e.g., facility bed count, ownership status) was associated with rate of acute care use within 30 days of SNF discharge.

Table 2.

Adjusted hazard ratios for acute care use within 30 days after SNF discharge

| Predictor | Adjusted Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

|---|---|

| Age (per yr) | 1.01 (1.00 to 1.02) |

| Men | 1.04 (0.87 to 1.24) |

| Race (reference: white) | |

| Black | 1.25 (1.04 to 1.51) |

| Other | 0.77 (0.33 to 1.52) |

| North Carolina (reference: South Carolina) | 0.87 (0.72 to 1.06) |

| Dual Medicare-Medicaid coverage | 1.24 (1.03 to 1.49) |

| ICD-9 Surveillance Diagnostic Group (reference: other)a | |

| Neoplasms | 1.24 (0.56 to 2.34) |

| Cardiovascular | 1.39 (0.91 to 2.02) |

| Cerebrovascular | 1.46 (0.94 to 2.17) |

| Respiratory | 0.86 (0.61 to 1.17) |

| Cellulitis, abscess, ulcer | 2.59 (1.36 to 4.45) |

| Fractures | 1.26 (0.92 to 1.70) |

| SNF length of stay | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.00) |

| Charlson comorbidity score | 1.07 (1.01 to 1.12) |

| Hospitalizations before SNF stayb | 1.12 (1.03 to 1.22) |

| Home health use (reference: none) | 0.72 (0.59 to 0.87) |

| SNF number of beds (reference: 0–50 beds) | |

| 51–100 | 1.21 (0.76 to 1.98) |

| 101–150 | 1.25 (0.80 to 2.02) |

| ≥151 | 1.27 (0.76 to 2.16) |

| Ownership status (reference: nonprofit) | |

| For-profit | 0.86 (0.65 to 1.17) |

| Government | 1.36 (0.66 to 2.57) |

| Staffing measures (h per resident per d) | |

| Registered nurse | 0.93 (0.76 to 1.10) |

| Licensed practical nurse | 0.95 (0.70 to 1.27) |

Hazard ratios are derived from a multivariable regression model of only variables included in this table. Acute care use refers to composite outcome of ED use or hospitalization within 30 days after SNF discharge.

ICD-9 Surveillance Diagnostic Group is defined as the diagnostic group that includes the primary hospital discharge diagnosis for each patient.

Hospitalizations before SNF stay is defined as number of hospitalizations in the 90 days before the index SNF stay.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to describe acute care use after SNF discharge in older adults with ESRD. Nearly half (43%) of cohort members were hospitalized or seen in the ED within the first 30 days after SNF discharge, and by 90 days after discharge, most patients (66%) had some acute care use. Although several patient characteristics (race, dual enrollment status, higher comorbidity score, prior hospitalizations) were predictive of acute care use within 30 days of SNF discharge, none of the SNF characteristics were associated with time to first acute care use after SNF discharge. However, use of home health services was associated with a lower rate of acute care use. This study highlights an under-recognized problem with the care transition from SNF to home for older adults with ESRD.

Our study demonstrates that older adults with ESRD have substantially higher rates of acute care use after SNF discharge than have been reported in the wider population of older Medicare beneficiaries. Rates of acute care use within 30 days of SNF discharge among patients with ESRD were >2-fold those reported for the broader population of older Medicare beneficiaries discharged home after a post–acute SNF stay (20.9 visits per 1000 patient-days versus 8.6 visits per 1000 patient-days) (1). At each time point after discharge, the proportion of patients using acute care services was at least 2-fold that among the broader population of Medicare beneficiaries (Figure 2) (1). Although it is possible that acute care use within 24 hours of SNF discharge might represent acute care admissions from the dialysis unit before planned SNF discharge, the overall incidence rate of acute care use during subsequent time periods was still extraordinarily high compared with the broader population of Medicare beneficiaries. Overall, the high rates of acute care use among members of this cohort likely reflect their high disease burden and clinical vulnerability demonstrated by higher Charlson comorbidity scores, more hospitalizations before SNF stay, and higher death rates than reported for the parent cohort (1).

These results highlight the importance of understanding modifiable risk factors of acute care use after SNF discharge in older adults with ESRD in order to identify interventions to curb acute care use in this population. Among members of this cohort, soft tissue infections at the time of SNF admission were strongly associated with acute care use within 30 days of SNF discharge and support the potential importance of efforts to optimize wound management among patients transitioning from SNF to home (21). Although none of the SNF organizational characteristics were associated with early acute care use in our study, prior studies have suggested that direct care hours per patient are associated with resident outcomes (22). Additional studies on SNF staffing patterns and care planning for older adults with ESRD may help confirm whether there are organizational characteristics that could be modified to improve acute care use after SNF discharge. A better understanding of how SNFs assess readiness for discharge and conduct discharge planning in patients with ESRD might also help to identify opportunities to reduce acute care use after these patients transition home.

Transitional care interventions may reduce acute care use after SNF discharge in older adults with ESRD. Transitional care interventions (e.g., The Care Transitions Intervention, Transitional Care Model, and Project ReEngineered Discharge) improve 30-day rehospitalization rates through the following key strategies: medication review, standardized discharge planning (e.g., appointment scheduling and patient education), and routine home visits starting within days of discharge (6,7,9,10). Routine home visits bridge care between the inpatient setting and home through the use of advanced practice nurses who assess symptoms and help patients and/or caregivers manage medications for multiple chronic conditions and navigate their environment (6,9). In considering transitional care interventions for SNF residents with ESRD, it should be noted that rates of acute care use in our cohort were highest in the first 30 days after SNF discharge, and home health use was significantly associated with lower rates of acute care use. Thus, a concentrated effort of transitional care interventions, specifically timely follow-up appointments and home visits, in the first 30 days after SNF discharge may yield considerably lower acute care utilization (23). These transitional care interventions could also address the unique challenges of older adults with ESRD, such as dialysis time constraints and progressive functional decline (14).

This study has the following limitations. First, the study was conducted using Medicare claims, which are known to be insensitive (24,25). Second, use of the Medicare denominator file rather than linkage to the US Renal Data System to ascertain ESRD may have resulted in incomplete capture of patients with ESRD in the parent cohort. Third, we used Medicare claims to define clinical characteristics and ICD-9 SDG codes to define primary hospital discharge diagnosis, but we were unable to test associations of individual diagnoses within each SDG. In addition, information that might be important in understanding patterns of acute care use after SNF discharge was not available in our limited data set for this project (e.g., length of time on dialysis, dialysis modality and access type, chief complaint at time of acute care use, detailed information on clinical status at time of SNF discharge, adequacy of caregiver support, quality of discharge planning and care coordination). Finally, it is unclear whether our findings are generalizable to younger adults (aged <65 years) with ESRD who are admitted to SNFs.

Older adults with ESRD have markedly higher rates of acute care use within 30 days of SNF discharge than reported for the wider population of older Medicare beneficiaries (1,2). In this cohort of older adults with ESRD, rates of acute care use after SNF discharge were higher among black patients, among those with Medicare-Medicaid dual enrollment, among those with a higher burden of comorbidity, and among those with hospital diagnoses of soft tissue infections. Rates were lower among those who received home health services after SNF discharge. Collectively, these findings highlight the significant risk of acute care use after SNF discharge among patients with ESRD and suggest that there may be untapped opportunities to improve care transitions and limit acute care use in this population.

Disclosures

A.M.O. and C.C.-E. receive royalties from UpToDate.

Acknowledgments

This publication is based on analyses performed by The Carolinas Center for Medical Excellence under contract number 500–2011-NC10C (Utilization and Quality Control Peer Review Organization for the State of North Carolina) and contract number 500–2011-SC10C (Utilization and Quality Control Peer Review Organization for the State of South Carolina), funded by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, an agency of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. government. The authors assume full responsibility for the accuracy and completeness of the ideas presented.

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P30AG028716. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Hall was also supported by the Office of Academic Affiliations, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. The content of this manuscript does not reflect the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “Overlooked Care Transitions: An Opportunity to Reduce Acute Care Use in ESRD,” on pages 347–349.

References

- 1.Toles M, Anderson RA, Massing M, Naylor MD, Jackson E, Peacock-Hinton S, Colón-Emeric C: Restarting the cycle: Incidence and predictors of first acute care use after nursing home discharge. J Am Geriatr Soc 62: 79–85, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ottenbacher KJ, Karmarkar A, Graham JE, Kuo YF, Deutsch A, Reistetter TA, Al Snih S, Granger CV: Thirty-day hospital readmission following discharge from postacute rehabilitation in fee-for-service Medicare patients. JAMA 311: 604–614, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA: Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med 360: 1418–1428, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naylor MD, Aiken LH, Kurtzman ET, Olds DM, Hirschman KB: The care span: The importance of transitional care in achieving health reform. Health Aff (Millwood) 30: 746–754, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coleman EA, Boult C, American Geriatrics Society Health Care Systems Committee : Improving the quality of transitional care for persons with complex care needs. J Am Geriatr Soc 51: 556–557, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naylor MD, Brooten DA, Campbell RL, Maislin G, McCauley KM, Schwartz JS: Transitional care of older adults hospitalized with heart failure: A randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 52: 675–684, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jack BW, Chetty VK, Anthony D, Greenwald JL, Sanchez GM, Johnson AE, Forsythe SR, O’Donnell JK, Paasche-Orlow MK, Manasseh C, Martin S, Culpepper L: A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: A randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 150: 178–187, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feltner C, Jones CD, Cené CW, Zheng ZJ, Sueta CA, Coker-Schwimmer EJ, Arvanitis M, Lohr KN, Middleton JC, Jonas DE: Transitional care interventions to prevent readmissions for persons with heart failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 160: 774–784, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min SJ: The care transitions intervention: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 166: 1822–1828, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berkowitz RE, Fang Z, Helfand BK, Jones RN, Schreiber R, Paasche-Orlow MK: Project ReEngineered Discharge (RED) lowers hospital readmissions of patients discharged from a skilled nursing facility. J Am Med Dir Assoc 14: 736–740, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crews DC, Scialla JJ, Liu J, Guo H, Bandeen-Roche K, Ephraim PL, Jaar BG, Sozio SM, Miskulin DC, Tangri N, Shafi T, Meyer KB, Wu AW, Powe NR, Boulware LE: Developing evidence to inform decisions about effectiveness patient outcomes in end stage renal disease study investigators: Predialysis health, dialysis timing, and outcomes among older United States adults. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 370–379, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forrest GP: Inpatient rehabilitation of patients requiring hemodialysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 85: 51–53, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan KE, Lazarus JM, Wingard RL, Hakim RM: Association between repeat hospitalization and early intervention in dialysis patients following hospital discharge. Kidney Int 76: 331–341, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holley JL: Palliative care in end-stage renal disease: Illness trajectories, communication, and hospice use. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 14: 402–408, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jassal SV, Chiu E, Hladunewich M: Loss of independence in patients starting dialysis at 80 years of age or older. N Engl J Med 361: 1612–1613, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woolley DC, Old JL, Zackula RE, Davis N: Acute hospital admissions of hospice patients. J Palliat Med 16: 1515–1522, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wallace SP, Levy-Storms L, Kington RS, Andersen RM: The persistence of race and ethnicity in the use of long-term care. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 53: S104–S112, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martins D, Tareen N, Norris KC: The epidemiology of end-stage renal disease among African Americans. Am J Med Sci 323: 65–71, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA: Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol 45: 613–619, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mor V, Zinn J, Angelelli J, Teno JM, Miller SC: Driven to tiers: Socioeconomic and racial disparities in the quality of nursing home care. Milbank Q 82: 227–256, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Curran T, Zhang JQ, Lo RC, Fokkema M, McCallum JC, Buck DB, Darling J, Schermerhorn ML: Risk factors and indications for readmission after lower extremity amputation in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. J Vasc Surg 60: 1315–1324, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Konetzka RT, Stearns SC, Park J: The staffing-outcomes relationship in nursing homes. Health Serv Res 43: 1025–1042, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Erickson KF, Winkelmayer WC, Chertow GM, Bhattacharya J: Physician visits and 30-day hospital readmissions in patients receiving hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 2079–2087, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zaslavsky AM, Ayanian JZ, Zaborski LB: The validity of race and ethnicity in enrollment data for Medicare beneficiaries. Health Serv Res 47: 1300–1321, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jollis JG, Ancukiewicz M, DeLong ER, Pryor DB, Muhlbaier LH, Mark DB: Discordance of databases designed for claims payment versus clinical information systems. Implications for outcomes research. Ann Intern Med 119: 844–850, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]